), 佟佳庚1, 于宏1, 王爱君2(

), 佟佳庚1, 于宏1, 王爱君2( )

) 1辽宁师范大学心理学院; 辽宁省儿童青少年健康人格评定与培养协同创新中心, 大连 116029

2苏州大学 心理学系, 心理与行为科学研究中心, 苏州 215123

收稿日期:2021-01-08出版日期:2021-11-25发布日期:2021-09-23通讯作者:唐晓雨,王爱君E-mail:tangyu2006@163.com;ajwang@suda.edu.cn基金资助:辽宁师范大学2020年高端科研成果培育资助计划项目(GD20L002);辽宁省教育厅2021年度科学研究经费面上项目(LJKZ0987)Effects of endogenous spatial attention and exogenous spatial attention on multisensory integration

TANG Xiaoyu1( ), TONG Jiageng1, YU Hong1, WANG Aijun2(

), TONG Jiageng1, YU Hong1, WANG Aijun2( )

) 1School of Psychology, Liaoning Collaborative Innovation Center of Children and Adolescents Healthy Personality Assessment and Cultivation, Liaoning Normal University, Dalian 116029, China

2Department of Psychology, Research Center for Psychology and Behavioral Sciences, Soochow University, Suzhou 215123, China

Received:2021-01-08Online:2021-11-25Published:2021-09-23Contact:TANG Xiaoyu,WANG Aijun E-mail:tangyu2006@163.com;ajwang@suda.edu.cn摘要/Abstract

摘要: 本文采用内-外源性空间线索靶子范式, 操控内源性线索有效性(有效线索、无效线索)、外源性线索有效性(有效线索、无效线索)、目标刺激类型(视觉刺激、听觉刺激、视听觉刺激)三个自变量。通过两个不同任务难度的实验(实验1: 简单定位任务; 实验2: 复杂辨别任务)来考察内外源性空间注意对多感觉整合的影响。两个实验结果均发现外源性空间注意显著减弱了多感觉整合效应, 内源性空间注意没有显著增强多感觉整合效应; 实验2中还发现了内源性空间注意会对外源性空间注意减弱多感觉整合效应产生影响。结果表明, 与内源性空间注意不同, 外源性空间注意对多感觉整合的影响不易受任务难度的调控; 当任务较难时内源性空间注意会影响外源性空间注意减弱多感觉整合效应的过程。由此推测, 内外源性空间注意对多感觉整合的调节并非彼此独立、而是相互影响的。

图/表 10

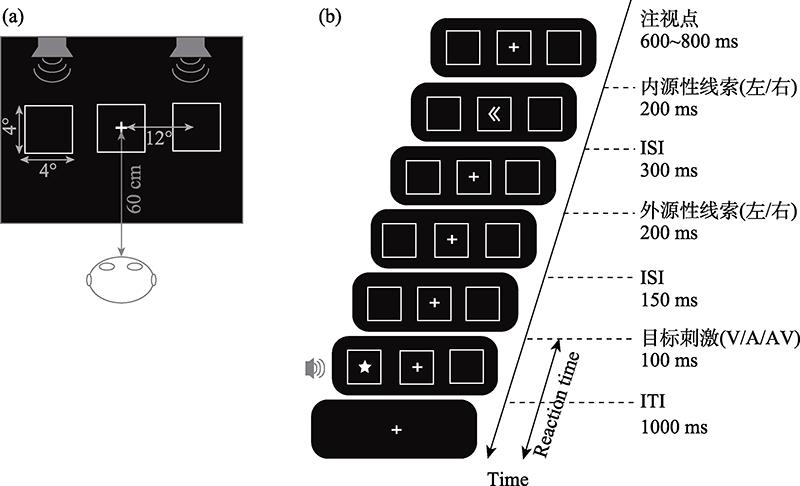

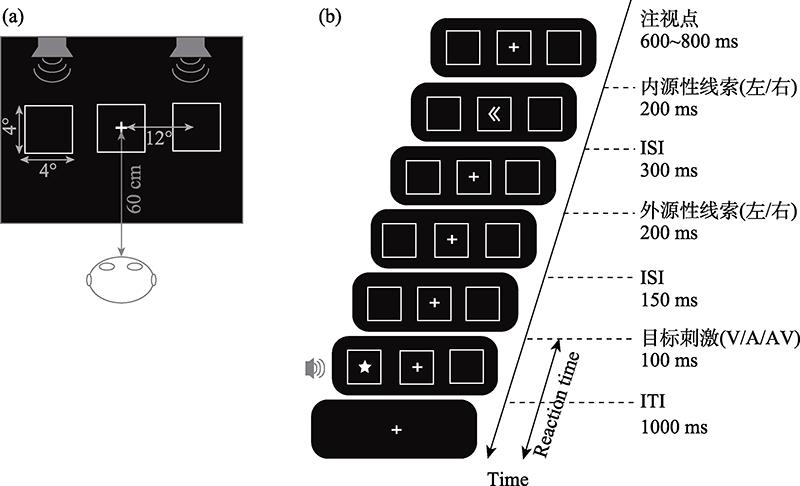

图1实验1流程示意图 注: 图1(a)为目标刺激呈现位置的示意图, 图1(b)为单个试次的流程图。右图中内源性空间线索对接下来的目标刺激的空间位置有80%的预测性, 而外源性空间线索对目标刺激位置没有预测性。目标刺激(V/A/AV)分别表示视觉刺激, 听觉刺激和视听觉刺激。

图1实验1流程示意图 注: 图1(a)为目标刺激呈现位置的示意图, 图1(b)为单个试次的流程图。右图中内源性空间线索对接下来的目标刺激的空间位置有80%的预测性, 而外源性空间线索对目标刺激位置没有预测性。目标刺激(V/A/AV)分别表示视觉刺激, 听觉刺激和视听觉刺激。

图1实验1流程示意图 注: 图1(a)为目标刺激呈现位置的示意图, 图1(b)为单个试次的流程图。右图中内源性空间线索对接下来的目标刺激的空间位置有80%的预测性, 而外源性空间线索对目标刺激位置没有预测性。目标刺激(V/A/AV)分别表示视觉刺激, 听觉刺激和视听觉刺激。表1实验1不同条件下的反应时(RT/ms)和正确率(ACC/%) (M ± SD)

| 目标刺激类型 | 内源有效 | 内源无效 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 外源有效 | 外源无效 | 外源有效 | 外源无效 | |

| 视觉通道 | ||||

| RT (ms) | 390.92 ± 57.34 | 408.06 ± 65.76 | 404.22 ± 54.76 | 413.42 ± 64.94 |

| ACC (%) | 98.75 ± 1.38 | 97.19 ± 2.33 | 98.02 ± 2.50 | 96.16 ± 3.86 |

| 视听觉通道 | ||||

| RT (ms) | 330.15 ± 36.51 | 357.75 ± 45.41 | 339.71 ± 37.18 | 368.74 ± 42.60 |

| ACC (%) | 99.36 ± 0.72 | 98.27 ± 1.54 | 99.41 ± 1.44 | 97.33 ± 3.07 |

| 听觉通道 | ||||

| RT (ms) | 361.03 ± 42.10 | 432.79 ± 78.71 | 373.75 ± 41.18 | 448.32 ± 82.17 |

| ACC (%) | 98.97 ± 1.20 | 94.33 ± 4.22 | 98.52 ± 1.94 | 91.27 ± 5.35 |

表1实验1不同条件下的反应时(RT/ms)和正确率(ACC/%) (M ± SD)

| 目标刺激类型 | 内源有效 | 内源无效 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 外源有效 | 外源无效 | 外源有效 | 外源无效 | |

| 视觉通道 | ||||

| RT (ms) | 390.92 ± 57.34 | 408.06 ± 65.76 | 404.22 ± 54.76 | 413.42 ± 64.94 |

| ACC (%) | 98.75 ± 1.38 | 97.19 ± 2.33 | 98.02 ± 2.50 | 96.16 ± 3.86 |

| 视听觉通道 | ||||

| RT (ms) | 330.15 ± 36.51 | 357.75 ± 45.41 | 339.71 ± 37.18 | 368.74 ± 42.60 |

| ACC (%) | 99.36 ± 0.72 | 98.27 ± 1.54 | 99.41 ± 1.44 | 97.33 ± 3.07 |

| 听觉通道 | ||||

| RT (ms) | 361.03 ± 42.10 | 432.79 ± 78.71 | 373.75 ± 41.18 | 448.32 ± 82.17 |

| ACC (%) | 98.97 ± 1.20 | 94.33 ± 4.22 | 98.52 ± 1.94 | 91.27 ± 5.35 |

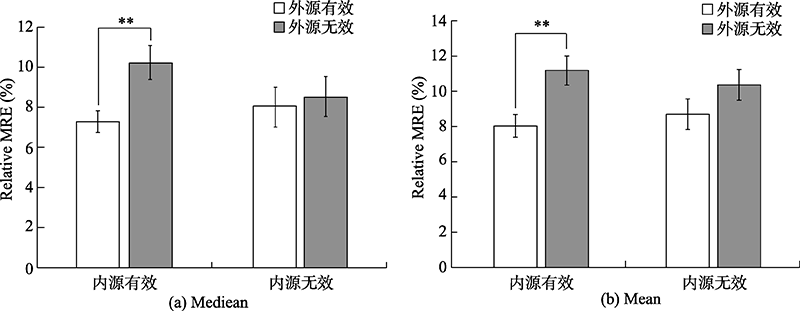

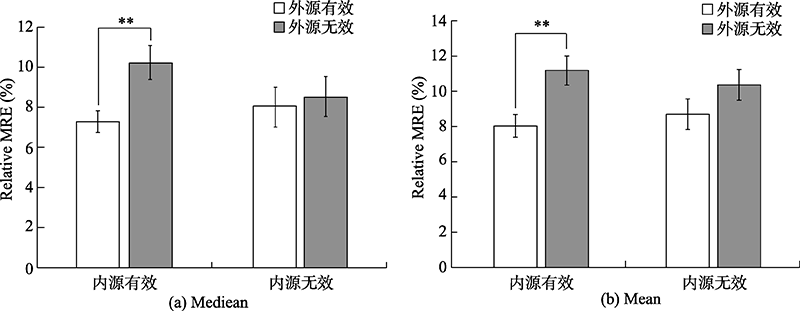

图2(a)是反应时为中位数时, 不同线索条件下rMRE结果; (b)是反应时为平均数时, 不同线索条件下rMRE的结果。 注:rMRE (相对多感觉反应增强; relative amount of multisensory response enhancement); **p < 0.01。

图2(a)是反应时为中位数时, 不同线索条件下rMRE结果; (b)是反应时为平均数时, 不同线索条件下rMRE的结果。 注:rMRE (相对多感觉反应增强; relative amount of multisensory response enhancement); **p < 0.01。

图2(a)是反应时为中位数时, 不同线索条件下rMRE结果; (b)是反应时为平均数时, 不同线索条件下rMRE的结果。 注:rMRE (相对多感觉反应增强; relative amount of multisensory response enhancement); **p < 0.01。

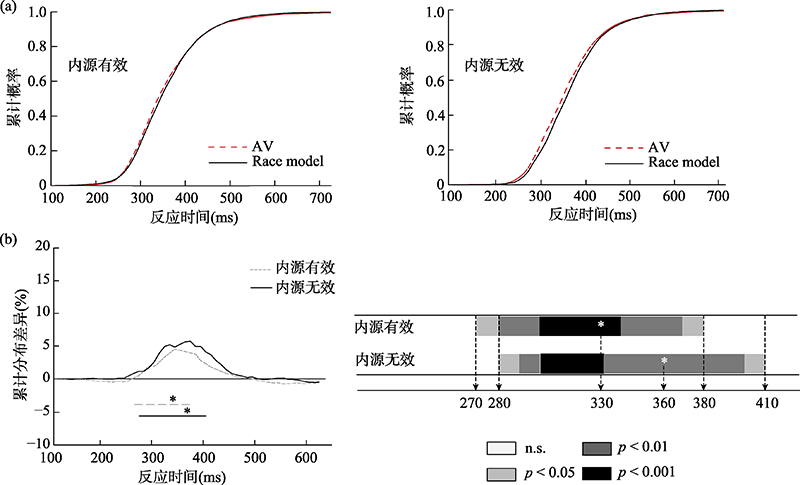

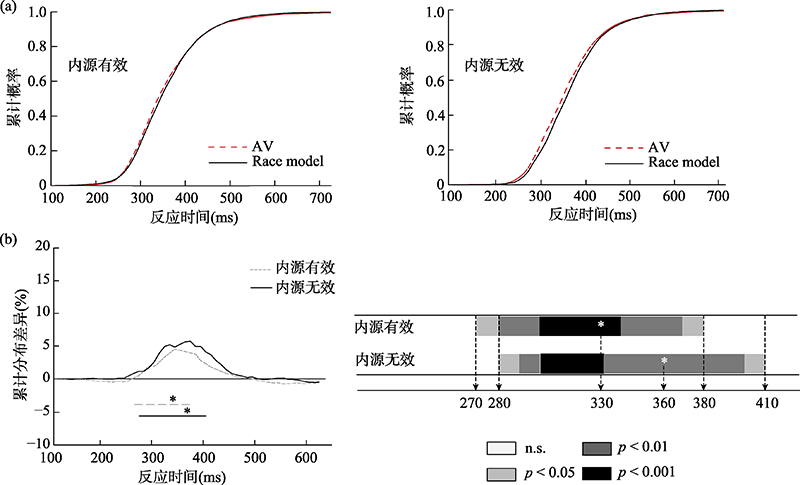

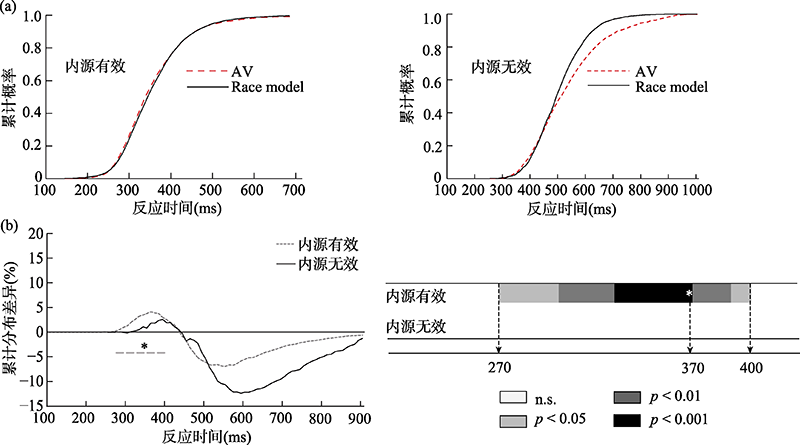

图3(a)是实验1内源性线索的累计概率分布; (b)是实验1内源性线索race model结果 注:粗线表示视听觉刺激发生显著整合的时间窗口。虚线表示有效线索, 实线表示无效线索。*代表峰值(最大概率值)出现的时间。

图3(a)是实验1内源性线索的累计概率分布; (b)是实验1内源性线索race model结果 注:粗线表示视听觉刺激发生显著整合的时间窗口。虚线表示有效线索, 实线表示无效线索。*代表峰值(最大概率值)出现的时间。

图3(a)是实验1内源性线索的累计概率分布; (b)是实验1内源性线索race model结果 注:粗线表示视听觉刺激发生显著整合的时间窗口。虚线表示有效线索, 实线表示无效线索。*代表峰值(最大概率值)出现的时间。

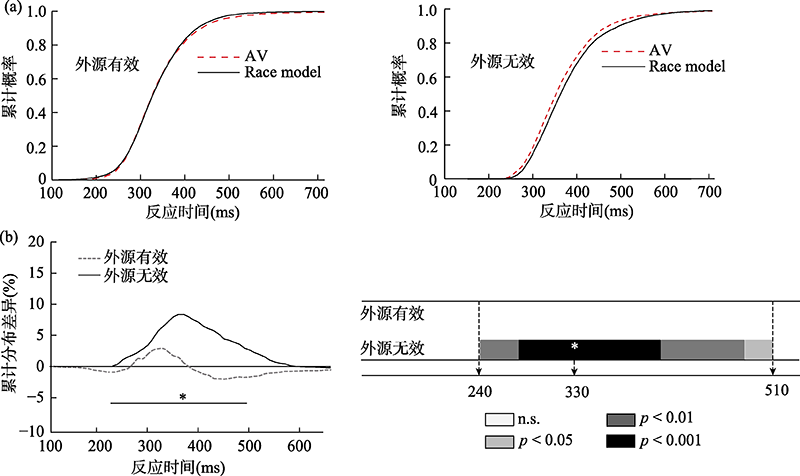

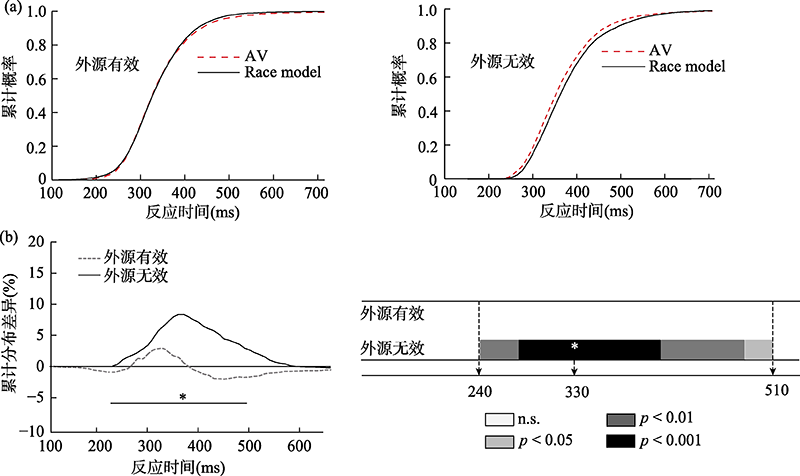

图4(a)是实验1外源性线索的累计概率分布; (b)是实验1外源性线索race model结果 注:粗线表示视听觉刺激发生显著整合的时间窗口。虚线表示有效线索, 实线表示无效线索。*代表峰值(最大概率值)出现的时间。

图4(a)是实验1外源性线索的累计概率分布; (b)是实验1外源性线索race model结果 注:粗线表示视听觉刺激发生显著整合的时间窗口。虚线表示有效线索, 实线表示无效线索。*代表峰值(最大概率值)出现的时间。

图4(a)是实验1外源性线索的累计概率分布; (b)是实验1外源性线索race model结果 注:粗线表示视听觉刺激发生显著整合的时间窗口。虚线表示有效线索, 实线表示无效线索。*代表峰值(最大概率值)出现的时间。

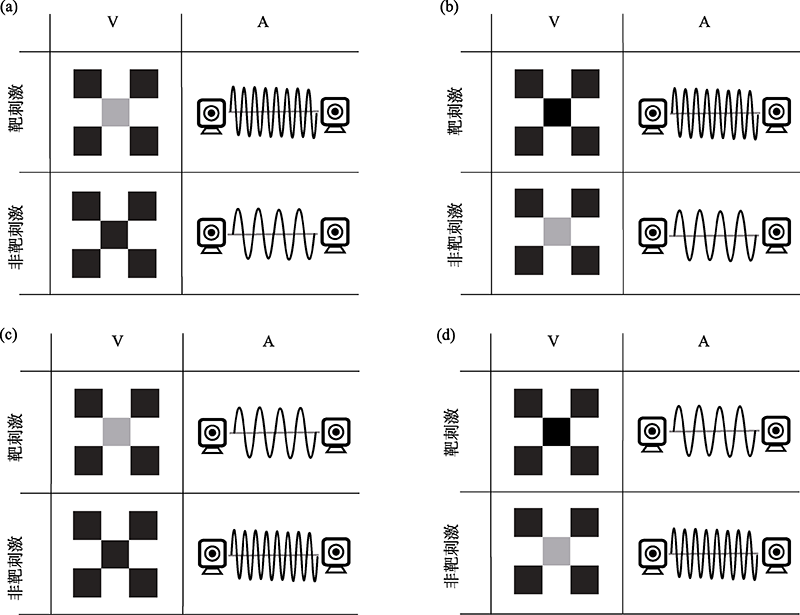

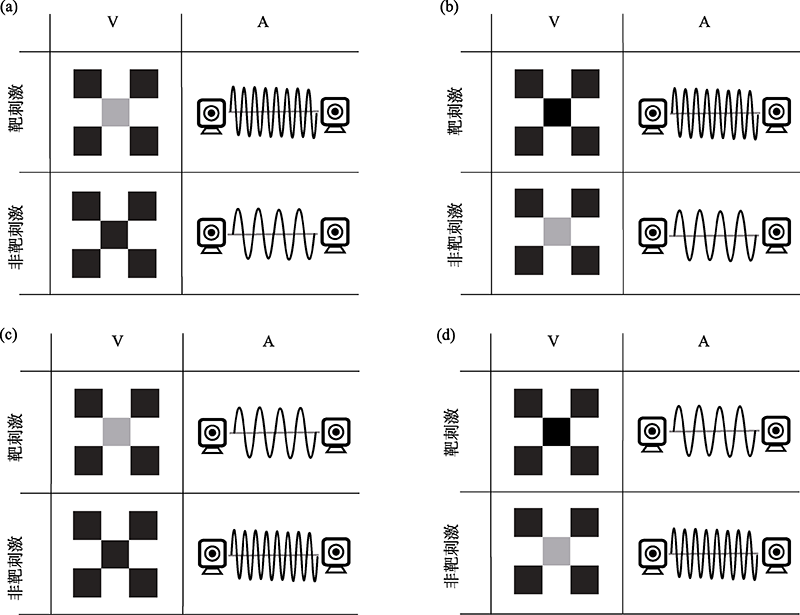

图5实验2目标刺激类型 注:图5为实验2四个种类的目标刺激。实验2的任务是判断目标靶刺激的空间位置, 并且不对非靶刺激反应。

图5实验2目标刺激类型 注:图5为实验2四个种类的目标刺激。实验2的任务是判断目标靶刺激的空间位置, 并且不对非靶刺激反应。

图5实验2目标刺激类型 注:图5为实验2四个种类的目标刺激。实验2的任务是判断目标靶刺激的空间位置, 并且不对非靶刺激反应。表2实验2在不同条件下的反应时(RT/ms)和正确率(ACC/%) (M ± SD)

| 目标刺激类型 | 内源有效 | 内源无效 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 外源有效 | 外源无效 | 外源有效 | 外源无效 | |

| 视觉通道 | ||||

| RT (ms) | 462.68 ± 41.87 | 499.19 ± 52.29 | 526.97 ± 54.44 | 577.86 ± 72.07 |

| ACC (%) | 97.17 ± 2.35 | 93.61 ± 4.29 | 88.55 ± 5.96 | 82.14 ± 7.24 |

| 视听觉通道 | ||||

| RT (ms) | 437.68 ± 48.56 | 466.07 ± 55.96 | 482.93 ± 71.26 | 513.86 ± 67.59 |

| ACC (%) | 98.82 ± 0.86 | 97.67 ± 1.68 | 96.50 ± 2.00 | 94.70 ± 3.89 |

| 听觉通道 | ||||

| RT (ms) | 494.43 ± 55.11 | 554.21 ± 75.59 | 499.29 ± 55.99 | 576.97 ± 72.94 |

| ACC (%) | 97.52 ± 1.70 | 95.38 ± 3.28 | 96.00 ± 2.82 | 92.14 ± 5.45 |

表2实验2在不同条件下的反应时(RT/ms)和正确率(ACC/%) (M ± SD)

| 目标刺激类型 | 内源有效 | 内源无效 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 外源有效 | 外源无效 | 外源有效 | 外源无效 | |

| 视觉通道 | ||||

| RT (ms) | 462.68 ± 41.87 | 499.19 ± 52.29 | 526.97 ± 54.44 | 577.86 ± 72.07 |

| ACC (%) | 97.17 ± 2.35 | 93.61 ± 4.29 | 88.55 ± 5.96 | 82.14 ± 7.24 |

| 视听觉通道 | ||||

| RT (ms) | 437.68 ± 48.56 | 466.07 ± 55.96 | 482.93 ± 71.26 | 513.86 ± 67.59 |

| ACC (%) | 98.82 ± 0.86 | 97.67 ± 1.68 | 96.50 ± 2.00 | 94.70 ± 3.89 |

| 听觉通道 | ||||

| RT (ms) | 494.43 ± 55.11 | 554.21 ± 75.59 | 499.29 ± 55.99 | 576.97 ± 72.94 |

| ACC (%) | 97.52 ± 1.70 | 95.38 ± 3.28 | 96.00 ± 2.82 | 92.14 ± 5.45 |

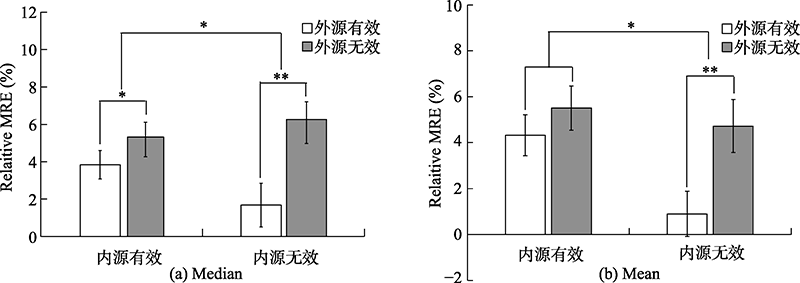

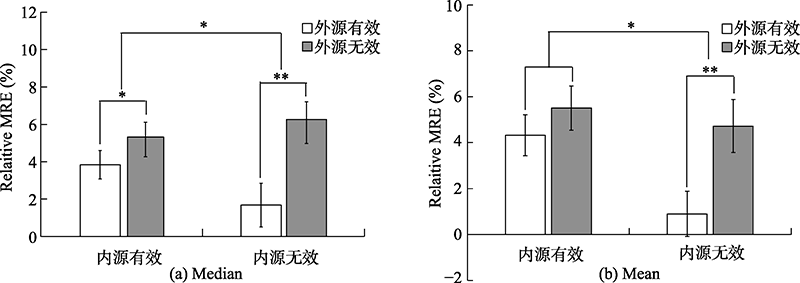

图6(a)是反应时为中位数时, 不同线索条件下rMRE结果; (b)是反应时为平均数时, 不同线索条件下rMRE的结果 注:rMRE (相对多感觉反应增强; relative amount of multisensory response enhancement); *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01。

图6(a)是反应时为中位数时, 不同线索条件下rMRE结果; (b)是反应时为平均数时, 不同线索条件下rMRE的结果 注:rMRE (相对多感觉反应增强; relative amount of multisensory response enhancement); *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01。

图6(a)是反应时为中位数时, 不同线索条件下rMRE结果; (b)是反应时为平均数时, 不同线索条件下rMRE的结果 注:rMRE (相对多感觉反应增强; relative amount of multisensory response enhancement); *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01。

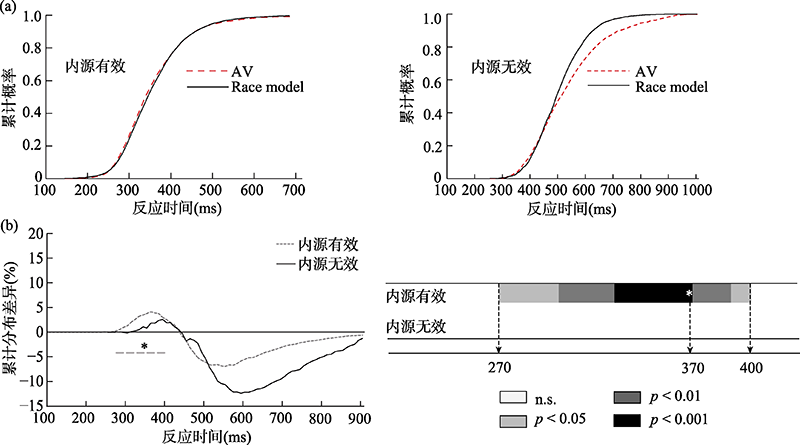

图7(a)是实验2内源性线索的累计概率分布; (b)是实验2内源性线索race model结果 注: 粗线表示视听觉刺激发生显著整合的时间窗口。虚线表示有效线索, 实线表示无效线索。*代表峰值(最大概率值)出现的时间。

图7(a)是实验2内源性线索的累计概率分布; (b)是实验2内源性线索race model结果 注: 粗线表示视听觉刺激发生显著整合的时间窗口。虚线表示有效线索, 实线表示无效线索。*代表峰值(最大概率值)出现的时间。

图7(a)是实验2内源性线索的累计概率分布; (b)是实验2内源性线索race model结果 注: 粗线表示视听觉刺激发生显著整合的时间窗口。虚线表示有效线索, 实线表示无效线索。*代表峰值(最大概率值)出现的时间。

图8(a)是实验2外源性线索的累计概率分布; (b)是实验2外源性线索race model结果 注: 粗线表示视听觉刺激发生显著整合的时间窗口。虚线表示有效线索, 实线表示无效线索。*代表峰值(最大概率值)出现的时间。

图8(a)是实验2外源性线索的累计概率分布; (b)是实验2外源性线索race model结果 注: 粗线表示视听觉刺激发生显著整合的时间窗口。虚线表示有效线索, 实线表示无效线索。*代表峰值(最大概率值)出现的时间。

图8(a)是实验2外源性线索的累计概率分布; (b)是实验2外源性线索race model结果 注: 粗线表示视听觉刺激发生显著整合的时间窗口。虚线表示有效线索, 实线表示无效线索。*代表峰值(最大概率值)出现的时间。参考文献 47

| [1] | Atchley P., Jones S. E., & Hoffman L. (2003). Visual marking: A convergence of goal-and stimulus-driven processes during visual search. Percept Psychophys, 65(5), 667. |

| [2] | Berger A., & Henik A. (2000). The endogenous modulation of IOR is nasal-temporal asymmetric. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 12(3), 421-428. |

| [3] | Berger A., Henik A., & Rafal R. (2005). Competition between endogenous and exogenous orienting of visual attention. Journal Experimental Psychology General, 134(2), 207-221. |

| [4] | Botta F., Lupiá?ez J., & Chica A. B. (2014). When endogenous spatial attention improves conscious perception: Effects of alerting and bottom-up activation. Consciousness & Cognition, 23, 63-73. |

| [5] | Burg E. V. D., Olivers C. N. L., Bronkhorst A. W., & Theeuwes J. (2008). Pip and pop: Non-spatial auditory signals improve spatial visual search. Journal of Experimental Psychology Human Perception & Performance, 34(5), 1053-1065. |

| [6] | Busse L., Katzner S., & Treue S. (2008). Temporal dynamics of neuronal modulation during exogenous and endogenous shifts of visual attention in macaque area MT. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 105(42), 16380-16385. |

| [7] | Chica A. B., Bartolomeo P., & Lupiá?ez J. (2013). Two cognitive and neural systems for endogenous and exogenous spatial attention. Behavioural Brain Research, 237, 107-123. |

| [8] | Corbetta M., & Shulman G. L. (2002). Control of goal-directed and stimulus-driven attention in the brain. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 3(3), 201. |

| [9] | Fairhall S. L., & Macaluso E. (2009). Spatial attention can modulate audiovisual integration at multiple cortical and subcortical sites. European Journal of Neuroscience, 29(6), 1247-1257. |

| [10] | Folk C. L., & Remington R. (1998). Selectivity in distraction by irrelevant featural singletons: Evidence for two forms of attentional capture. Journal of Experimental Psychology Human Perception & Performan, 24(3), 847. |

| [11] | Gowen E., Abadi R. V., Poliakoff E., Hansen P. C., & Miall R. C. (2007). Modulation of saccadic intrusion by exogenous and endogenous attention. Brain Research, 1141(1), 154-167. |

| [12] | Granholm E., Asarnow R. F., Sarkin A. J., & Dykes K. L. (1996). Pupillary responses index cognitive resource limitations. Psychophysiology, 33(4), 457-461. |

| [13] | Grubb M. A., White A. L., Heeger D. J., & Carrasco M. (2015). Interactions between voluntary and involuntary attention modulate the quality and temporal dynamics of visual processing. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 22(2), 437-444. |

| [14] | Grundy J. G., Barker R. M., Anderson J. A. E., & Shedden J. M. (2019). The relation between brain signal complexity and task difficulty on an executive function task. NeuroImage, 198, 104-113. |

| [15] | Gustavo R., Coull J. T., Nobre A. C., & Sam G. (2011). Behavioural dissociation between exogenous and endogenous temporal orienting of attention. Plos One, 6(1), e14620. |

| [16] | Hopfinger J. B., & West V.M. (2006). Interactions between endogenous and exogenous attention on cortical visual processing. NeuroImage, 31(2), 774-789. |

| [17] | Johnston W. A., & Heinz S.P. (1979). Depth of nontarget processing in an attention task. Journal of Experimental Psychology Human Perception & Performance, 5(1), 168. |

| [18] | Julia F. C., Daniel C., Beer A. L., & Daphne B. (2018). Neural bases of enhanced attentional control: Lessons from action video game players. Brain & Behavior, 8(7), e01019. |

| [19] | Kosslyn S. M., Thompson W. L., Wraga M., & Alpert N. M. (2001). Imagining rotation by endogenous versus exogenous forces: Distinct neural mechanisms. Neuroreport, 12(11), 2519-2525. |

| [20] | Lavie N. (1995). Perceptual load as a necessary condition for selective attention. Journal of Experimental Psychology Human Perception & Performance, 21(3), 451-468. |

| [21] | Lavie N. (2010). Attention, distraction, and cognitive control under load. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 19(3), 143-148. |

| [22] | Lunn J., Sjoblom A., Ward J., Soto-Faraco S., & Forster S. (2019). Multisensory enhancement of attention depends on whether you are already paying attention. Cognition, 187, 38-49. |

| [23] | Lupiá?ez J., Botta F., Martín-Arévalo E., Chica A. B. (2014). The spatial orienting paradigm: How to design and interpret spatial attention experiments. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 40, 35-51. |

| [24] | Mayer A. R., Dorflinger J. M., Rao S. M., & Seidenberg M. (2004). Neural networks underlying endogenous and exogenous visual-spatial orienting. Neuroimage, 23(2), 534-541. |

| [25] | Meyer K. N., Du F., Parks E., & Hopfinger J. B. (2018). Exogenous vs. endogenous attention: Shifting the balance of fronto-parietal activity. Neuropsychologia, 111, 307-316. |

| [26] | Miller J. (1982). Divided attention: Evidence for coactivation with redundant signals. Cognitive Psychology, 14(2), 247-279. |

| [27] | Odegaard B., Wozny D. R., & Shams L. (2016). The effects of selective and divided attention on sensory precision and integration. Neuroscience Letters, 614(9), 24-28. |

| [28] | Otten M., Schreij D., & Los S. A. (2016). The interplay of goal-driven and stimulus-driven influences on spatial orienting. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics, 78(6), 1642-1654. |

| [29] | Pauszek J. R., & Gibson B.S. (2016). High spatial validity is not sufficient to elicit voluntary shifts of attention. Attention Perception & Psychophysics, 78(7), 2110-2123. |

| [30] | Peelen M. V., Heslenfeld D. J., & Theeuwes J. (2004). Endogenous and exogenous attention shifts are mediated by the same large-scale neural network. NeuroImage, 22(2), 822-830. |

| [31] | Peng X., Chang R. S., Li Q., Wang A. J., & Tang X. Y. (2019). Visually induced inhibition of return affects the audiovisual integration under different SOA conditions. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 51(7), 759-771. |

| [ 彭姓, 常若松, 李奇, 王爱君, 唐晓雨. (2019). 不同SOA下视觉返回抑制对视听觉整合的调节作用. 心理学报, 51(7), 759-771.] | |

| [32] | Peng X., Chang R. S., Ren G. Q., Wang A. J., & Tang X. Y. (2018). The interaction between exogenous attention and multisensory integration. Advances in Psychological Science, 26(12), 43-54. |

| [ 彭姓, 常若松, 任桂琴, 王爱君, 唐晓雨. (2018). 外源性注意与多感觉整合的交互关系. 心理科学进展, 26(12), 43-54.] | |

| [33] | Posner M. I. (1980). Orienting of attention. Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 32(1), 3-25. |

| [34] | Senkowski D., Saint-Amour D., Hofle M., & Foxe J. J. (2011). Multisensory interactions in early evoked brain activity follow the principle of inverse effectiveness. NeuroImage, 56(4), 2200-2208. |

| [35] | Senkowski D., Talsma D., Herrmann C. S., & Woldorff M. G. (2005). Multisensory processing and oscillatory gamma responses: Effects of spatial selective attention. Experimental Brain Research, 166(3-4), 411-426. |

| [36] | Sugihara T., Diltz M. D., Averbeck B. B., & Romanski L. M. (2006). Integration of auditory and visual communication information in the primate ventrolateral prefrontal cortex. Journal of Neuroscience, 26(43), 11138-11147. |

| [37] | Talsma D., Doty T. J., & Woldorff M. G. (2007). Selective attention and audiovisual integration: Is attending to both modalities a prerequisite for early integration? Cerebral Cortex, 17(3), 679-690. |

| [38] | Talsma D., Senkowski D., Soto-Faraco S., & Woldorff M. G. (2010). The multifaceted interplay between attention and multisensory integration. Trends in Cognitive Science, 14(9), 400-410. |

| [39] | Talsma D., & Woldorff M. G. (2005). Selective attention and multisensory integration: Multiple phases of effects on the evoked brain activity. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 17(7), 1098-1114. |

| [40] | Tang X., Wu J., & Shen Y. (2016). The interactions of multisensory integration with endogenous and exogenous attention. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 61, 208-224. |

| [41] | Tang, X Y., Sun J. Y., & Peng X. (2020). The effect of bimodal divided attention on inhibition of return with audiovisual targets. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 52(3), 257-268. |

| [ 唐晓雨, 孙佳影, 彭姓. (2020). 双通道分配性注意对视听觉返回抑制的影响. 心理学报, 52(3), 257-268.] | |

| [42] | Tang, X Y., Wu Y. N., Peng X., Wang A. J., & Li Q. (2020). The influence of endogenous spatial cue validity on audiovisual integration. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 52(7), 835-846. |

| [ 唐晓雨, 吴英楠, 彭姓, 王爱君, 李奇. (2020). 内源性空间线索有效性对视听觉整合的影响. 心理学报, 52(7), 835-846.] | |

| [43] | van der Stoep N., van der Stigchel S., & Nijboer, T. C. W. (2015). Exogenous spatial attention decreases audiovisual integration. Attention, Perception, & Psychophysics, 77(2), 464-482. |

| [44] | van der Stoep N., van der Stigchel S., Nijboer T. C. W., & Spence C. (2016). Visually induced inhibition of return affects the integration of auditory and visual information. Perception, 46(1), 6-17. |

| [45] | Washburn D. A., & Putney R.T. (2001). Attention and task difficulty: When is performance facilitated?. Learning & Motivation, 32(1), 36-47. |

| [46] | Yantis S., & Jonides J. (1990). Abrupt visual onsets and selective attention: Voluntary versus automatic allocation. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception & Performance, 16(1), 121-134. |

| [47] | Yu, H. (2019). The effects of attention on multisensory integration (Unpublished master’s thesis). Liaoning Normal University, Dalian, China. |

| [ 于宏. (2019). 注意对多感觉整合的影响 (硕士学位论文). 辽宁师范大学, 大连. ] |

相关文章 10

| [1] | 唐晓雨, 吴英楠, 彭姓, 王爱君, 李奇. 内源性空间线索有效性对视听觉整合的影响[J]. 心理学报, 2020, 52(7): 835-846. |

| [2] | 彭姓, 常若松, 李奇, 王爱君, 唐晓雨. 不同SOA下视觉返回抑制对视听觉整合的调节作用[J]. 心理学报, 2019, 51(7): 759-771. |

| [3] | 于薇;王爱君;张明. 集中和分散注意对多感觉整合中听觉主导效应的影响[J]. 心理学报, 2017, 49(2): 164-173. |

| [4] | 马文娟,索涛,李亚丹,罗笠铢,冯廷勇,李红. 得失框架效应的分离—— 来自收益与损失型跨期选择的研究[J]. 心理学报, 2012, 44(8): 1038-1046. |

| [5] | 孙远路,胡中华,张瑞玲,寻茫茫,刘强,张庆林. 多感觉整合测量范式中存在的影响因素探讨[J]. 心理学报, 2011, 43(11): 1239-1246. |

| [6] | 刘强,胡中华,赵光,陶维东,张庆林,孙弘进. 通道估计可靠性先验知识在早期的知觉加工阶段影响多感觉信息整合[J]. 心理学报, 2010, 42(02): 227-234. |

| [7] | 杨继平,郑建君. 情绪对危机决策质量的影响[J]. 心理学报, 2009, 41(06): 481-491. |

| [8] | 刘希平,方格. 小学儿童学习时间分配决策水平的发展[J]. 心理学报, 2005, 37(05): 623-631. |

| [9] | 蔡厚德. 刺激的知觉辨认难度与大脑两半球间的分布式加工[J]. 心理学报, 2005, 37(01): 14-18. |

| [10] | 郑全全,刘方珍. 任务难度、决策培训诸因素对群体决策的影响[J]. 心理学报, 2003, 35(05): 669-676. |

PDF全文下载地址:

http://journal.psych.ac.cn/xlxb/CN/article/downloadArticleFile.do?attachType=PDF&id=5086