1. 中国科学院天津工业生物技术研究所 中国科学院系统微生物工程重点实验室,天津 300308;

2. 国家合成生物技术创新中心,天津 300308;

3. 天津科技大学 生物工程学院,天津 300457

收稿日期:2020-11-11;接收日期:2021-02-04

基金项目:国家重点研发计划(No. 2018YFA0903700),“重大新药创制”科技重大专项(No. 2018ZX09711001-006-003),国家自然科学基金(No. 31700080) 资助

作者简介:王钦宏? 中国科学院天津工业生物技术研究所研究员、博士生导师、副所长。国务院特殊津贴获得者,天津市创新人才推进计划创新团队入选者,荣获天津市五一劳动奖章等荣誉。主要从事工业微生物的进化与代谢工程研究,包括重要化学品高性能细胞工厂创制、基因组水平编辑和实验室进化筛选、液滴微流控高通量筛选平台搭建及应用等。近年来在Metab Eng、Biotechnol Biofuels、ACS Synth Biol、Anal Chem等领域主流国际期刊发表科研论文50余篇,获授权专利13项,参与了国家科学技术部、国家发展和改革委员会、中国科学院相关领域战略规划编制。现为学术期刊Scientific Reports和《生物工程学报》编委.

摘要:代谢工程从20世纪90年代初期发展至今已有近30年历史,对微生物菌种改良和选育工作起到了极大的推动作用。芳香族化合物是一类可以通过微生物发酵生产的化学品,广泛应用于医药、食品、饲料和材料等领域。利用代谢工程手段对莽草酸和芳香族氨基酸合成途径进行理性改造,微生物细胞可以定向地大量积累人们需要的各种芳香族化合物。笔者对近30年来国内外代谢工程改造微生物合成各种芳香族化合物的研究策略和生物合成途径进行了梳理和总结,以期为开展相关研究提供参考。

关键词:芳香族化合物芳香族氨基酸莽草酸途径代谢工程微生物发酵

Advances in metabolic engineering for the production of aromatic chemicals

Fengli Wu1,2, Xiaoshuang Wang1,2,3, Fuqiang Song1,2,3, Yanfeng Peng1,2, Qinhong Wang1,2

1. CAS Key Laboratory of Systems Microbial Biotechnology, Tianjin Institute of Industrial Biotechnology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Tianjin 300308, China;

2. National Technology Innovation Center of Synthetic Biology, Tianjin 300308, China;

3. College of Biotechnology, Tianjin University of Science & Technology, Tianjin 300457, China

Received: November 11, 2020; Accepted: February 4, 2021

Supported by: National Key Research and Development Program of China (No. 2018YFA0903700), Drug Innovation Major Project (No. 2018ZX09711001-006-003), National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31700080)

Corresponding author: Qinhong Wang. Tel: +86-22-84861950; E-mail: wang_qh@tib.cas.cn.

Abstract: Metabolic engineering has been developed for nearly 30 years since the early 1990s, and it has given a great impetus to microbial strain breeding and improvement. Aromatic chemicals are a variety of important chemicals that can be produced by microbial fermentation and are widely used in the pharmaceutical, food, feed, and material industry. Microbial cells can be engineered to accumulate a variety of useful aromatic chemicals in a targeted manner through rational engineering of the biosynthetic pathways of shikimate and the derived aromatic amino acids. This review summarizes the metabolic engineering strategies and biosynthetic pathways for the production of aromatic chemicals developed in the past 30 years, with the aim to provide a valuable reference and promote the research in this field.

Keywords: aromatic chemicalsaromatic amino acidshikimate pathwaymetabolic engineeringmicrobial fermentation

芳香族化合物(Aromatic chemicals) 是一类重要的微生物发酵化学品,广泛应用于医药、化工、食品和饲料等领域[1-3]。莽草酸途径(Shikimate pathway) 是生物体合成芳香族化合物的基础途径,广泛存在于植物、藻类、真菌和细菌等细胞内[4-5]。在自然条件下,芳香族化合物在微生物细胞中的含量很低,难以满足发酵生产的需求。通过代谢工程手段,对细胞内的中心代谢途径和莽草酸途径进行理性改造,必要时引入异源合成途径,使细胞具有更强的目的产物合成能力或合成新的芳香族化合物的能力[1]。此外,植物来源的木质素、单宁酸等复杂有机质通过微生物发酵也可以转化为某些重要的芳香族化合物及其衍生物[6-8]。近30年来,微生物合成芳香族化合物的代谢工程研究取得了一系列重要研究进展,并且许多芳香族化合物已经实现工业化发酵生产(图 1),在国民经济乃至世界经济的发展过程中发挥着重要的推动作用。本文中,笔者主要对微生物生产各种芳香族化合物的代谢工程研究策略和合成途径进行梳理和总结,以期为工业发酵菌种的优化改造研究提供参考。

|

| 图 1 芳香族化合物代谢工程研究发展历程(部分示意图节选自参考文献[9-13]。SA:莽草酸shikimate;L-Tyr:L-酪氨酸L-tyrosine;pABA:对氨基苯甲酸p-aminobenzoic acid:紫色杆菌素violacein;DHS:3-脱氢莽草酸3-dehydroshikimate;L-DOPA:左旋多巴;L-Phe:L-苯丙氨酸L-phenylalanine;L-Trp:L-色氨酸L-tryptophan;MA:顺, 顺-粘康酸cis, cis-muconic acid;苯甲酸benzoic acid;PCA:原儿茶酸protocatechuic acid) Fig. 1 Advances in metabolic engineering for the production of aromatic chemicals. |

| 图选项 |

1 芳香族化合物生物合成途径芳香族化合物生物合成的基础代谢途径涉及糖酵解途径(Glycolytic pathway或Embden- Meyerhof-Parnas pathway,EMP)、磷酸戊糖途径(Pentose phosphate pathway,PPP) 和莽草酸途径(Shikimate pathway)。莽草酸途径以糖酵解途径产生的磷酸烯醇式丙酮酸(Phosphoenolpyruvate,PEP) 和磷酸戊糖途径产生的赤藓糖-4-磷酸(D-erythrose 4-phosphate,E4P) 为前体,缩合生成3-脱氧-D-阿拉伯庚酮糖-7-磷酸(3-deoxy-D- arabino-heptulosonate-7-phosphate,DAHP)。DAHP再经过莽草酸途径的六步催化反应生成分支酸。以分支酸为前体,通过两条途径将分支酸分别转化为3种芳香族氨基酸,其中一条途径首先转化为预苯酸,然后分别合成L-苯丙氨酸(L-phenylalanine,L-Phe) 或L-酪氨酸(L-tyrosine,L-Tyr),另一条经由邻氨基苯甲酸生成L-色氨酸(L-tryptophan,L-Trp)。其中莽草酸途径中间代谢产物3-脱氢莽草酸(3-dehydroshikimate,DHS) 和上述3种芳香族氨基酸,通过代谢途径的理性设计可以衍生为多种芳香族衍生物。近30年来发展起来的各种代谢工程研究策略为芳香族衍生物的生物合成研究提供行之有效的解决方案。

2 芳香族化合物代谢工程研究策略2.1 途径工程受氨基酸和核苷酸等生产菌株代谢工程策略的启发,鄢芳清等[14]认为芳香族化合物生物合成途径的代谢工程改造策略也可以总结为“进” “通” “节” “堵” “出” 5个字。

“进”:增加代谢流量,例如加快底物(如葡萄糖) 向细胞内的转运、增加前体物质供应等(图 2)。当以葡萄糖为碳源时,大肠杆菌Escherichia coli利用磷酸转移酶转运系统(Phosphoenolpyruvate:carbohydrate phosphotransferase system,PTS) 将胞外一分子葡萄糖转运至胞内生成一分子葡萄糖-6-磷酸的同时,伴随消耗一分子PEP[15]。用非PTS型葡萄糖转运系统代替PTS系统可以减少莽草酸途径底物PEP的消耗。将来源于大肠杆菌的半乳糖透性酶GalP或运动发酵单胞菌Zymomonas mobilis的葡萄糖透性酶Glf与葡萄糖激酶Glk进行共表达,既增加葡萄糖向胞内的转运,又减少胞内PEP的消耗,显著提高莽草酸途径的代谢流量[16-17]。E4P是莽草酸途径的另一个前体物质。过表达转酮醇酶基因tktA可以增加E4P的供应,从而增加莽草酸途径的代谢流量[18]。

|

| 图 2 芳香族氨基酸生物合成途径 Fig. 2 Biosynthetic pathway of aromatic amino acids. PTS: Phosphoenolpyruvate: carbohydrate phosphotransferase system; GalP: galactose permease; Glk: glucokinase; TnaB: low affinity tryptophan transporter; Mtr: high affinity tryptophan transporter; AroP: aromatic amino acid transporter; TyrP: L-tyrosine-specific transporter; YddG: aromatic amino acid exporter; Pgi: glucose-6-phosphate isomerase; TktA: transketolase Ⅰ; Tal: transaldolase; PpsA: phosphoenolpyruvate synthase; PykA/PykF: pyruvate kinase; AroF/AroG/AroH: 3-deoxy-D-arabino-heptulosonate- 7-phosphate synthase; AroB: 3-dehydroquinate synthase; AroD: 3-dehydroquinate dehydratase; AroE: dehydroshikimate reductase; AroK/AroL: shikimate kinase; AroA: EPSP synthase; AroC: chorismate synthase; PheA: chorismate mutase/prephenate dehydratase; TyrA: chorismate mutase/prephenate dehydrogenase; TyrB: aromatic-amino-acid transaminase; AspC: aspartate aminotransferase; TrpED: anthranilate synthase complex; TrpC: bifunctional phosphoribosylanthranilate isomerase/indole-3-glycerol phosphate synthase; TrpBA: tryptophan synthase complex; TnaA: tryptophanase. PEP: phosphoenolpyruvate; PYR: pyruvate; G6P: glucose-6-phosphate; F6P: fructose-6-phosphate; FBP: fructose-1, 6-biphosphate; GAP: glyceraldehde-3-phosphate; BPG: 1, 3-bisphosphoglycerate; Ru5P: ribulose-5-phosphate; R5P: ribose-5-phosphate; X5P: xylulose-5-phosphate; S7P: sedoheptulose-7-phosphate; E4P: D-erythrose 4-phosphate; DAHP: 3-deoxy-D-arabino-heptulosonate-7-phosphate; DHQ: 3-dehydroquinate; DHS: 3-dehydroshikimate; SA: shikimate; S3P: shikimate-3-phosphate; EPSP: 5-enolpyruvylshikimate 3-phosphate; CHA: chorismate; PRE: prephenate; PP: phenylpyruvate; 4HPP: 4-hydroxyphenylpyruvate; ANT: anthranilate; PRPP: 5-phosphoribosyl 1-pyrophosphate; PRANT: 5-phosphoribosylanthranilate; IGP: indole-3-glycerol phosphate; IND: indole. |

| 图选项 |

“通”:使合成途径畅通,例如解除产物反馈抑制、增加关键酶基因的表达量或酶活力、敲除负调控因子基因等(图 2)。芳香族氨基酸生物合成途径有两个关键的节点受代谢产物的反馈抑制,分别是催化PEP和E4P缩合的DAHP合成酶和催化分支酸进入芳香族氨基酸合成途径的双功能酶分支酸变位酶/预苯酸脱水酶或邻氨基苯甲酸合成酶。大肠杆菌DAHP合成酶有3种,分别为AroG、AroF、AroH。它们分别受L-苯丙氨酸、L-酪氨酸和L-色氨酸的反馈抑制,其中AroG和AroF起主要催化作用[19]。代谢工程改造也主要对AroG和AroF突变体进行表达调控。目前,已报道多种有效的AroG和AroF解除反馈抑制的突变体,过表达这些突变体基因(aroGfbr和aroFfbr) 可以显著增加莽草酸途径的代谢流量[14, 18, 20-21]。另一个关键节点分支酸变位酶/预苯酸脱水酶(pheA和tyrA编码) 或邻氨基苯甲酸合成酶(trpE编码),分别控制合成L-苯丙氨酸、L-酪氨酸和L-色氨酸,并受对应氨基酸的反馈抑制。过表达相应突变体基因(pheAfbr、tyrAfbr、trpEfbr) 可以显著提高相应氨基酸的产量[14, 22-25]。此外,细胞中还存在负调控转录因子。例如转录因子TyrR对莽草酸途径中关键基因aroF、aroG和aroL以及L-苯丙氨酸和L-酪氨酸合成途径中tyrB的表达起负调控作用,敲除tyrR可以显著提高上述酶的催化活性[26]。另一个转录因子TrpR对L-色氨酸的合成也起负调控作用[25, 27]。

“节”:阻断或弱化代谢副产物合成途径,使代谢流量更多地流向目标产物。芳香族化合物合成途径有3处关键的分节点需要进行代谢流量调控,分别是葡萄糖-6-磷酸进入EMP和PPP途径节点、PEP进入莽草酸途径和转化为丙酮酸节点、分支酸进入3种芳香族氨基酸合成途径节点(图 2)。(1) 提高磷酸戊糖途径代谢流量比例,增加莽草酸途径前体E4P的供应。野生型大肠杆菌在以葡萄糖为碳源时,进入EMP和PPP的碳代谢流量比例大约分别为73%和27%[9, 28],导致细胞内E4P与PEP的比例极其不平衡。对EMP途径中的6-磷酸葡萄糖异构酶基因pgi进行弱化调控,促使代谢流量进入PPP途径,提高细胞内E4P的比例。(2) 增加莽草酸途径前体PEP的供应。在自然条件下,PEP主要转化为丙酮酸,只有少量的PEP进入莽草酸途径[9, 28]。敲除丙酮酸激酶基因pykF或pykA,减少PEP转化为丙酮酸,可以显著提高莽草酸途径中间代谢产物的产量[29-30]。在敲除pykA的同时,过表达磷酸烯醇丙酮酸合酶基因ppsA,可以进一步提高DHS的产量[30]。(3) 阻断分支酸到其他芳香族氨基酸支路途径,促使细胞积累某一种芳香族氨基酸。例如在构建高产L-苯丙氨酸菌株时,阻断L-酪氨酸合成途径,有利于提高L-苯丙氨酸产量[22, 31];反之,则用来构建高产L-酪氨酸菌株[32-33]。L-色氨酸合成途径代谢流量很小,又存在反馈抑制效应,因此在构建L-苯丙氨酸或L-酪氨酸高产菌株时,无需改造L-色氨酸合成途径。在构建高产L-色氨酸菌株时,阻断L-苯丙氨酸和L-酪氨酸合成途径有利于提高L-色氨酸产量[34];但是由于存在反馈抑制效应,未阻断这两个分支途径也可获得较高的L-色氨酸产量[24-25],表明只要保证L-色氨酸合成途径的畅通,该分支途径就不是影响L-色氨酸生物合成的主要因素。

“堵”:阻断目标产物降解途径,促进产物积累(图 2)。例如DHS是莽草酸途径中的代谢中间产物。在构建高产DHS菌株时,敲除莽草酸脱氢酶基因aroE虽然可以阻断DHS到下游产物的转化,但是由于细胞无法继续合成芳香族氨基酸、叶酸等重要营养物质,导致发酵培养时需要向培养基中添加这些物质或者添加大量的酵母粉、蛋白胨等有机营养成分[30, 35]。笔者所在课题组利用弱启动子和将起始密码子ATG替换为TTG组合弱化调控的方式弱化aroE的表达,促使细胞积累DHS,这样既不影响细胞生长,又无需添加外源营养物质[36]。色氨酸酶(TnaA) 催化L-色氨酸转化为吲哚和L-丝氨酸,敲除该基因可以减少L-色氨酸降解[37-38]。通过敲除转运蛋白,减少胞外产物向胞内转运也可以提高目标产物的产量,如L-酪氨酸特异性转运蛋白[23]、L-色氨酸透性酶[39]等。

“出”:增加目标产物向细胞外运输,降低产物反馈抑制或细胞毒性(图 2)。过表达芳香族氨基酸外排蛋白基因yddG可以降低产物的反馈抑制效应,从而提高芳香族氨基酸产量[24, 31, 40]。利用水相-有机相两相发酵的方式,将目的产物不断萃取到有机相,可以减弱目的产物的细胞毒性。

2.2 高通量筛选技术对于基因组水平或单个基因的随机突变体文库筛选,需要具备高通量的筛选技术,例如流式细胞术、液滴微流控等分选技术,将阳性突变体从复杂的文库中有效地筛选出来。高通量筛选技术依赖于稳定、高效的检测信号或指标,如荧光信号、颜色或吸光度信号、生长速率变化指标等。

2.2.1 基于荧光信号变化筛选基于荧光信号变化筛选大多数是采用转录因子类型的传感器。笔者所在课题组利用转录组测序技术筛选出能够特异性响应DHS浓度变化的基因cusR,将其与绿色荧光蛋白基因gfp进行融合表达,形成能够特异性响应胞内DHS浓度变化的生物传感器,然后分别利用流式细胞术和液滴微流控筛选技术从随机突变体文库中成功筛选出DHS产量显著提高的突变体[41-42]。Liu等[43]利用转录因子ShiR和其作用的靶基因shiA启动子序列构建响应莽草酸浓度变化的生物传感器,从表达tktA的RBS文库突变体中成功筛选出莽草酸产量提高90%的菌株。基于转录因子TyrR和PadR的生物传感器也分别在大肠杆菌和酿酒酵母Saccharomyces cerevisiae中实现了L-苯丙氨酸[44]和对香豆酸[45]高产菌株的筛选。Chen等[46]利用不动杆菌Acinetobacter baylyi ADP1来源的Psal启动子和SalR调节系统,在大肠杆菌中开发并表征了一种简单、灵敏的阿司匹林诱导生物传感器SalR/Psal。利用不同强度的启动子以及Psal启动子,分别尝试了简单调节基因线路(SRS) 和自动调节基因线路(PAR),并证明在0.05–1.00 μmol/L阿司匹林浓度范围内,两种基因线路都以剂量依赖性的方式发挥调控作用。虽然目前已经实现了水杨酸的从头合成,但是由于缺乏有效的乙酰基转移酶,尚未发现由水杨酸进一步合成阿司匹林的报道。笔者认为阿司匹林生物传感器的开发可能有助于筛选有效的乙酰基转移酶。

除了转录因子类型的传感器外,Abatemarco等[10]开发了一种基于RNA Spinach-based aptamers类型的传感器,将胞外产物浓度变化转化为荧光信号,实现了L-酪氨酸高产菌株的筛选,并证明可以应用于L-苯丙氨酸和L-色氨酸高产菌株的筛选。

某些关键中间代谢产物(如E4P、PEP) 供应直接影响芳香族化合物的产量。因此,构建响应中间代谢产物的生物传感器也可以间接表征目标产物的合成能力。为了实现对中心代谢途径(如EMP和PPP) 代谢物的实时监控,Ding等[47]以人源的次黄嘌呤-鸟嘌呤磷酸核糖转移酶为配体结合域,通过酶定向进化技术分别建立了5-磷酸核糖-1-焦磷酸、E4P和3-磷酸甘油酸生物传感器。然后结合流式筛选提高了E4P生物传感器的响应度,并将该元件成功应用于筛选高产L-苯丙氨酸菌株的代谢工程改造。这项工作不仅为实时动态检测EMP与PPP途径的代谢过程提供了很好的技术支撑,也为大范围分子生物传感器的计算设计及开发提供了一种新的研究策略。

2.2.2 基于颜色或吸光度变化筛选L-酪氨酸是黑色素的合成前体。在产L-酪氨酸的大肠杆菌中表达酪氨酸酶基因会导致菌落变黑,并且在一定浓度范围内,黑色深浅与L-酪氨酸产量的高低呈正相关[48]。利用该筛选技术,在基于全局性转录调控因子随机突变体文库中成功筛选到3株L-酪氨酸产量提高91%–113%的高产菌株[33]。笔者所在研究组利用对香豆酸在310 nm处有特异性吸收峰的特性,建立了对香豆酸含量的高通量检测方法,利用该方法从酪氨酸解氨酶随机突变体文库中筛选到了催化活性提高1倍的突变体[49]。

2.2.3 基于生长速率指标筛选将细胞的生长速率与酶活性或产物浓度相耦合,生长速率越快,酶活性或代谢物产量越高,从而在突变体文库中筛选出酶活性或产量显著提高的突变体。Liu等[44]将TyrR传感器中的报告基因yfp替换成链霉素抗性基因strA,因此突变菌株的L-苯丙氨酸产量越高,细胞在抗性平板上生长的速率越快。通过4轮突变筛选,L-苯丙氨酸产量提高菌株的阳性率达68.9%,其中产量最高提升了160.2%。Kramer等[50]利用大肠杆菌作为宿主细胞,阻断NADPH到NADH的转化,导致胞内积累大量NADPH,引起细胞还原力失衡,菌株生长极其缓慢。然后利用该菌株筛选NADPH依赖型的羧酸还原酶突变体文库,使胞内的NADPH/NADP+趋于平衡,细胞生长速率明显加快;酶催化活力越高,细胞生长速率越快,由此筛选到酶活力显著提高的突变体。该系统也可以应用于其他NADPH依赖型催化酶突变体文库的筛选。

2.3 基因精细表达调控细胞内的代谢网络是由许多代谢途径组成的复杂网络系统,而每条代谢途径一般是由多个酶分子构成的催化反应。每种催化酶基因表达量既要满足催化反应的需要,又不能过量表达而引起代谢网络的失衡。利用不同强度的启动子元件或RBS元件对靶基因进行转录水平或翻译水平的精细表达调控是一种常用又十分有效的代谢工程调控手段。用大肠杆菌自身GalP-Glk系统代替PTS系统可以减少胞内PEP的消耗,为莽草酸途径提供更多的合成前体。Lu等[51]利用筛选的3种不同强度(强、中、弱) 的启动子对galP和glk的表达进行组合调控,获得既有利于提高葡萄糖利用效率,又减少胞内PEP消耗的最佳的启动子组合。为了平衡莽草酸途径和三羧酸循环途径的碳流量,Kim等[52]利用5种不同强度的5′-非翻译区序列(包含RBS) 对ppsA的表达进行翻译后调控,获得的最佳调控菌株的L-酪氨酸合成能力比对照菌株提高了大约7倍。

此外,模块化调控也是一种有效的代谢工程调控手段,即将代谢途径基因分成几个功能互补的调控模块,然后对每个模块分别进行调控,从而获得最佳的调控组合。Lin等[53]设计了一条新的顺, 顺-粘康酸合成途径,分别用低、中、高拷贝数的质粒对大肠杆菌内源的分支酸合成模块、异源的水杨酸和顺, 顺-粘康酸合成模块进行组合调控,使顺, 顺-粘康酸产量提升了275倍。

2.4 辅因子工程代谢途径中的许多催化反应需要辅因子(如NADH/NAD+、NADPH/NADP+、FADH2/FAD等)的参与,例如脱氢反应、还原反应、羟化反应等等。虽然这些辅因子在细胞内的含量较低,但是如果打破辅因子平衡往往会影响细胞内物质和能量代谢的正常运行。因此,增加合成反应所需类型的还原力供给或构建辅因子循环再生体系有利于提高某些化合物的产量。芳香族氨基酸生物合成途径有两个催化反应需要辅因子NADPH/ NADP+的参与,其中一个是莽草酸脱氢酶催化DHS生成莽草酸的反应,需要NADPH参与;另一个是预苯酸脱氢酶催化预苯酸生成4-羟基苯丙酮酸的反应,需要NADP+参与[54]。因此,根据合成途径分析,DHS和L-酪氨酸的合成途径辅因子循环体系是平衡的,但是合成莽草酸和L-苯丙氨酸等化合物的合成辅因子是失衡的,需要增加胞内NADPH供应。Kogure等[55]通过检测不同莽草酸菌株的胞内辅因子和ATP的含量,发现莽草酸产量高的菌株胞内NADPH/NADP+比例显著低于产量低的菌株,表明莽草酸的合成消耗大量的NADPH。另有研究报道,过表达葡萄糖-6-磷酸脱氢酶基因zwf [29]、转氢酶基因pantAB或NAD激酶基因nadK[56]均可以提高胞内NADPH/NADP+的比例,从而增强莽草酸的合成能力。Liu等[44]通过筛选L-苯丙氨酸工程菌株的突变体文库,发现pantB (A167T) 和nadK (A145V) 基因点突变显著提高了L-苯丙氨酸的产量。

其他芳香族衍生物的生物合成也需要辅因子的参与,例如没食子酸、2-苯乙醇、L-苯乳酸、酪醇、左旋多巴等。因此,这些物质的生物合成除了要提高相应催化酶的酶活力以外,构建胞内辅因子循环再生体系也非常重要。为了提高2-苯乙醇的产量,Wang等[57]利用谷氨酸脱氢酶的脱氨和NAD(P)H再生活性,将芳香族氨基酸转氨酶和醇脱氢酶催化反应连接在一起,构成NAD(P)H循环再生系统,利用全细胞催化的方式将L-苯丙氨酸转化为2-苯乙醇。

2.5 适应性进化利用实验室适应性进化(Adaptive laboratory evolution,ALE) 技术可以对生长受限的菌株(如生长缓慢、对某种产物敏感、底物利用率低等)按照设定的培养条件进行适应性驯化改良,逐渐自发积累有益突变,从而提高工程菌的发酵生产性能[58]。利用该技术,Kr?mer等[59]通过29次传代培养,将酿酒酵母对对氨基苯甲酸的耐受性浓度由0.62 g/L逐渐提高至1.65 g/L,驯化菌株的生长速率达到野生型菌株的88.5%。笔者所在研究组为了促进对香豆酸的生物合成,将前体菌——高产L-酪氨酸菌株在含有较高浓度对香豆酸的培养基中进行驯化传代培养,逐渐提高菌株的耐受性,为L-酪氨酸到对香豆酸的生物合成提供合适的前体菌株(数据未发表)。

2.6 定向进化许多芳香族化合物生物合成途径的催化酶来源于其他物种,并且这些异源酶的催化活性往往不能满足宿主细胞大量合成目标产物的需求,从而成为生物合成途径中的限速步骤。酶定向进化技术大大加快了酶活性改造的效率,为芳香族化合物的代谢工程研究提供有效的技术手段。天然的4-羟基苯甲酸羟化酶PobA催化4-羟基苯甲酸转化为原儿茶酸,其突变体Y385F可以进一步催化原儿茶酸羟化生成没食子酸[60],但是催化活性较低。Chen等[11]对PobAY385F突变体催化中心位点关键氨基酸进行理性设计分析,通过酶活性检测成功筛选出新的突变体PobAY385F, T294A。该突变体对两种底物4-羟基苯甲酸和原儿茶酸的催化效率分别提高了4.5倍和4.3倍,全细胞催化的4-羟基苯甲酸生成没食子酸,摩尔转化率达到93%。

2.7 全细胞或体外酶催化对于某些合成途径较为复杂或产物毒性较强或消耗大量辅酶的芳香族化合物,利用简单、廉价的碳源从头合成的方式难以达到较高的产量或转化率,采用表达关键酶的细胞进行全细胞催化或利用未纯化的粗酶液或纯化酶液进行体外催化的方式有利于获得更高的产量或转化率。由于原儿茶酸具有较强的细胞毒性,笔者所在研究组前期以葡萄糖为碳源进行从头合成,只能获得大约33.3 g/L的原儿茶酸[61]。后来采用间接合成的方式,首先通过补料发酵获得高浓度的DHS底物(> 90 g/L),然后利用表达3-脱氢莽草酸脱水酶的大肠杆菌进行全细胞催化,获得85 g/L以上的原儿茶酸,基本检测不到DHS残留(数据未发表)。Romasi和Lee[62]在大肠杆菌中过表达氨基转移酶基因aspC、吲哚-3-丙酮酸脱羧酶基因idpC和吲哚-3-乙酸脱氢酶基因iad1,同时敲除色氨酸酶基因tnaA,该菌株以4 g/L的L-色氨酸为底物催化反应24 h获得3 g/L的吲哚-3-乙酸。体外生物酶催化具有产物专一、副产物少、易于纯化、不受产物毒性抑制等优点。利用葡萄糖脱氢酶GDH的辅酶再生功能,将其与消耗还原型辅酶的羧酸还原酶CAR相耦合,可以将含有羧基的化合物(如苯甲酸、苯甲酸的氯代或甲氧基化合物、反式肉桂酸等) 转变为相应的醛类化合物,并且具有很强的立体选择性[63]。

2.8 产物毒性控制许多芳香族化合物具有细胞毒性,例如没食子酸、原儿茶酸、对氨基苯甲酸、2-苯乙醇、苯乙烯、酪醇等。因此,研究人员尝试了多种方法来降低产物的细胞毒性,提高细胞合成芳香族化合物的能力。

2.8.1 选用耐受性强的宿主或提高宿主的耐受能力上文提到,利用ALE技术可以对宿主细胞进行驯化改良,提高菌株的发酵生产性能。此外,选用耐受性更强的天然宿主细胞也是一种有效的备选方案。不同的宿主细胞对不同化学物质的耐受能力不同。选用耐受性强的宿主细胞有利于获得更高的产量或转化率。Kubota等[64]比较谷氨酸棒状杆菌Corynebacterium glutamicum、大肠杆菌、酿酒酵母、恶臭假单胞菌Pseudomonas putida 4种宿主对对氨基苯甲酸的耐受性,发现谷氨酸棒状杆菌在含有400 mmol/L对氨基苯甲酸的培养基中仍然能够生长,其他3种细胞的耐受性浓度均不超过200 mmol/L,因此选取谷氨酸棒状杆菌作为合成对氨基苯甲酸的宿主细胞。

2.8.2 利用全细胞催化或体外酶催化方式上文提到,对于有细胞毒性的芳香族化合物,采用全细胞催化或体外酶催化的生产方式有助于避免产物对细胞产生毒性作用。

2.8.3 将目标化合物转化为无毒产物将有毒的芳香族化合物转化为无毒的衍生物或转化为沉淀形式,然后采用化学方法再转化为目标产物。醛类化合物的化学稳定性较差,很难在细胞内大量积累。Hansen等[65]首先在裂殖酵母Schizosaccharomyces pombe中整合3个外源基因,分别为3-脱氢莽草酸脱水基因3dsd、芳香族羧酸还原酶基因acar、O-甲基转移酶基因omt,敲除醇脱氢酶基因adh6,使细胞能够积累香草醛。通过表达异源的UDP葡萄糖基转移酶,促使香草醛转化为无毒的香草醛β-D-葡萄糖苷,细胞的合成能力得到进一步提升。当对氨基苯甲酸与还原性糖(如葡萄糖、甘露糖、木糖、阿拉伯糖等) 共存时,氨基与还原糖的醛基会自发形成糖基化产物,该产物在酸性条件下会水解为原来的两种物质[64]。糖基化产物的形成可能有助于降低氨基苯甲酸类物质的细胞毒性。

除了目标产物外,某些副产物的生成也会抑制细胞生长。沸石是一种天然的多孔水合铝硅酸盐材料,具有吸附NH4+的特性,可以用来降低脱氨类反应产生的NH4+对细胞的毒害。Wang等[57]在全细胞催化L-苯丙氨酸合成2-苯乙醇的反应液中添加1 g/L的沸石,底物的摩尔转化率由60.8%提高至74.4%。

2.8.4 采用水-有机两相发酵两相发酵是指利用目标产物在水相和有机相中的溶解度或分配系数差异,使产物从水相萃取到有机相中,达到产物和细胞分离的目的。该技术在2-苯乙醇和苯酚等有较强细胞毒性的芳香族化合物的发酵研究中得到了广泛应用[66-68]。

2.9 动态调控利用途径工程技术虽然可以显著提高目标产物的产量,但是往往会导致细胞出现各种生理问题,例如细胞内碳源和能源的过度消耗、有毒中间代谢产物积累、氧化还原系统失衡等,这些问题会严重影响细胞的生长。利用代谢途径动态调控技术可以动态调控细胞生长和目的产物的合成,使两者达到动态平衡,从而有利于目的产物合成达到最大化。动态调控方式主要分为以下3种类型:基于发酵参数的调控、基于代谢产物的调控、基于群体感应的调控[12]。为了促进顺, 顺-粘康酸的生物合成,Yang等[69]利用恶臭假单胞菌KT2440来源的特异性响应顺, 顺-粘康酸的转录因子CatR和其结合的catBCA启动子序列PMA,结合RNA干扰技术(RNAi),构建了能够平衡PEP在EMP和莽草酸途径中的代谢流量。首先,顺, 顺-粘康酸的积累抑制CatR的转录激活活性,促进顺, 顺-粘康酸合成途径基因的过表达;其次,CatR的转录激活活性被抑制,导致PEP羧化酶的表达水平下调,促进PEP进入莽草酸途径。相反,PEP则进入三羧酸循环途径进行分解代谢。Wu等[70]构建一系列受L-苯丙氨酸诱导的不同表达强度的启动子序列,然后利用这些启动子调控莽草酸途径中的关键基因aroK的表达,获得L-苯丙氨酸产量提高1.36倍的菌株。

除了上述策略以外,芳香族化合物的代谢工程研究还有许多其他策略,比如高通量组学分析技术,包括基因组学、转录组学、蛋白组学、代谢组学,以及将这些组学技术进行整合的多组学分析技术。这些组学分析技术有助于全面系统分析微生物生理代谢功能的状况以及可能出现的问题,提高了反向代谢工程中分析特殊生理表型可能存在的遗传调控机制。此外,利用质粒表达芳香族化合物合成途径的关键基因虽然相对容易获得产量较高工程菌株,但是质粒的不稳定性和对宿主细胞的代谢负担却是制约其应用于大规模工业化发酵生产的主要因素。通过基因组整合方式构建的工程菌株,虽然基因表达强度相对较弱、构建难度大,但是遗传稳定性好、无需添加抗生素、宿主代谢负担小。因此,该方法对于生产大宗化学品和某些精细化学品工程菌株的选育来说仍然是值得采用的构建方式。

3 芳香族衍生物合成途径拓展DHS、L-苯丙氨酸、L-酪氨酸、L-色氨酸分别是各自合成途径的重要平台化合物,可以进一步转化为许多重要的芳香族衍生物。因此,构建上述重要节点化合物的底盘细胞对于获得相应芳香族衍生物的高产细胞工厂具有重要意义。表 1列举了一些具有代表性的芳香族衍生物高产细胞工厂构建的研究进展。

表 1 一些代表性的芳香族衍生物微生物合成研究进展Table 1 Advances in microbial production of aromatic chemicals

| Product | Regulated genes | Host | Feedstock | Culture style | Titer (g/L) | References |

| 3-dehydroshikimate | Deletion of tyrR, ptsG and pykA. Overexpression of aroB, aroD, ppsA, galP, aroG and aroF in chromosome | E. coli | Glucose, glycerol, yeast extract, tryptone | Fed-batch | 117.0 | [30] |

| 3-dehydroshikimate | Deletion of ptsI and tyrR. Down-regulation of aroE, pykF, pykA and pgi, and overexpression of aroFfbr, tktA, galP and glk in chromosome | E. coli | Glucose | Fed-batch | 94.4 | [36] |

| cis, cis-muconic acid | Overexpression of absF, aroY and catA with plasmid in DHS chassis | E. coli | Glucose, glycerol, yeast extract, tryptone | Fed-batch | 64.5 | [30] |

| Shikimate | Deletion of aroL, aroK, ptsH-ptsI-crr, aroB and serA. Overexpression of glf, glk, aroFfbr, tktA, aroE and serA in plasmid | E. coli | Glucose, yeast extract | Fed-batch | 84.0 | [72] |

| Shikimate | Deletion of aroK, qusB, qusD, ptsH and hdpA. Overexpression of tkt, tal, iolT1, glk1, glk2, ppgk and gapA in chromosome, and aroGS180F, aroB, aroD and aroE in plasmid, respectively | C. glutamicum | Glucose, yeast extract, casamino acid | Fermenter-controlled growth-arrested cell reaction, 10% (W/V) wet cell weight | 141.2 | [55] |

| Protocatechuic acid | Deletion of qusD, pcaHG and poxF. Overexpression of aroGS180F, aroA, aroD, aroE, aroCKB, qusB, ubiC and pobA in chromosome | C. glutamicum | Glucose, yeast extract, casamino acid | Fermenter-controlled growth-arrested cell reaction, 10% (W/V) wet cell weight | 82.7 | [73] |

| p-aminobenzoic acid | Deletion of ldhA. Overexpression of aroB, aroD, aroE, aroK, aroA, aroC and aroGS180F in chromosome, and pabAB and pabC in plasmid, respectively | C. glutamicum | Glucose, yeast extract, casamino acid | Fed-batch | 43.0 | [64] |

| L-phenylalanine | Deletion of ptsH. Mutation of tyrR. Combinatorial modulation of galP and glk in chromosome. Overexpression of aroF, aroD, pheAT326P in plasmid | E. coli | Glucose, yeast extract | Fed-batch | 72.9 | [22] |

| 2-phenylethanol | Overexpression of tyrB, aro10 and par (or adh1) in plasmid | E. coli | L-phenylalanine, L-glutamic acid | Whole-cell biocatalyst | 9.14 | [57] |

| D-phenyllactic acid | Induction of pprA expression with plasmid in L-phenylalanine chassis | E. coli | Glucose | Fed-batch | 29.2 | [74] |

| Benzoic acid | Deletion of tyrA and yddG. Overexpression of aroL in chromosome. Induction of phdB, phdC, phdE, RgPAL and ScCCLA294G expression in plasmid | E. coli | Glucose | Fed-batch | 2.37 | [75] |

| L-tyrosine | Deletion of pheLA. Overexpression of tyrA in chromosome of L-phenylalanine chassis | E. coli | Glucose | Fed-batch | 55.0 | [32] |

| L-DOPA | Overexpression of aroE and hpaBC in chromosome of DHS chassis | E. coli | Glucose, yeast extract | Fed-batch | 57.0 | [76] |

| Hydrotxytyrosol | Deletion of hpaD and mhpB. Overexpression of gltS, nadA and pdxJ in chromosome, and co-expression of lcaro, bsgdh, pmkdc and ecadh2 in plasmid | E. coli | L-DOPA, L-glutamic acid | Whole-cell biocatalyst | 169.2 | [77] |

| Salvianic acid A | Deletion of ptsG, tyrR, pykA, pykF and pheA. Co-expression of aroGfbr, tyrAfbr, aroE, ppsA, tktA, glk, d-ldhY52A and hpaBC in plasmid | E. coli | Glucose, yeast extract | Fed-batch | 7.14 | [78] |

| L-tryptophan | Deletion of pta and mtr, and overexpression of yddG in chromosome of L-tryptophan chassis | E. coli | Glucose, yeast extract | Fed-batch | 48.68 | [24] |

| Violacein | Overexpression of vioA, vioB, vioC, vioD and vioE with plasmid in L-tryptophan chassis | C. glutamicum | Glucose, corn steep liquor | Fed-batch | 5.436 | [79] |

| Indole-3-acetic acid | Deletion of tnaA. Overexpression of aspC, idpC and iad1 in plasmid | E. coli | L-tryptophan | Whole-cell biocatalyst | 3.0 | [62] |

表选项

3.1 DHS底盘细胞构建及其衍生物的生物合成DHS是莽草酸途径中的一种代谢中间产物,既可作为一些化学合成制剂和药物的中间原料,还是一种十分有效的抗氧化剂[1]。DHS极易溶于水,化学性质较稳定,对细胞毒性很小,合成过程不需要额外消耗还原力和能量。因此,发酵过程中大量积累DHS,既不会抑制细胞生长,也不会扰乱细胞内辅酶和能量代谢平衡。对莽草酸途径起始化合物DAHP合成途径进行化学计量分析,将丙酮酸循环计算在内,DAHP相对于葡萄糖的理论摩尔转化率为86%[71]。因为一分子DHS对应一分子DAHP,所以DHS相对于葡萄糖的理论摩尔转化率也是86%。密歇根州立大学的J. W. Frost研究组通过质粒表达关键基因的方式,先后评价了转酮醇酶基因tktA、磷酸烯醇丙酮酸合酶基因ppsA、葡萄糖转运系统基因对增加莽草酸途径代谢产物的重要作用,利用无机盐培养基进行补料发酵,获得了一系列高产DHS菌株[16, 18, 35]。Choi等[30]在基因组上对DHS合成途径进行一系列遗传改造,获得高产DHS菌株InhaM103。该菌株在添加少量酵母粉、蛋白胨等有机物质的无机盐培养基中,以葡萄糖和甘油混合碳源为底物,补料发酵120 h积累117 g/L DHS。笔者所在研究组也通过在基因组上进行一系列遗传改造,获得DHS产量达94.4 g/L的高产菌株,所用发酵培养基为添加适量葡萄糖的无机盐培养基[36]。这些高产DHS菌株是构建下游芳香族氨基酸以及其他芳香族衍生物工程菌株的优良底盘细胞。

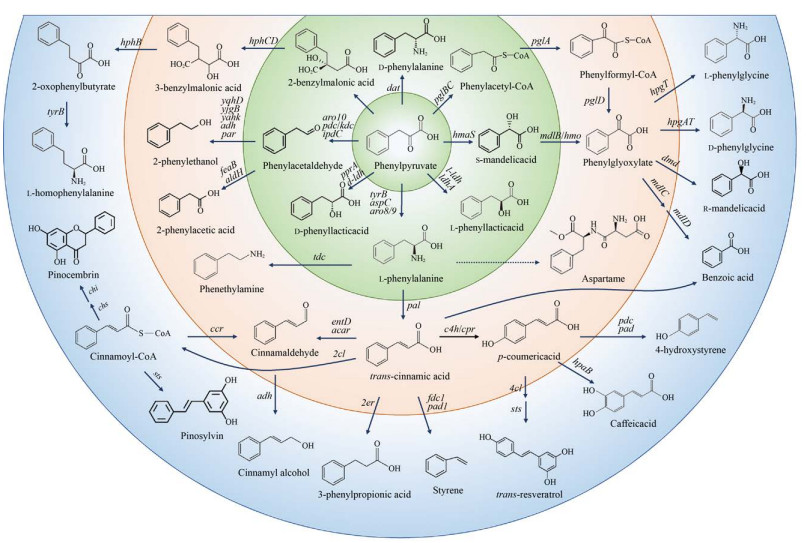

DHS作为平台化合物可以转化为多种芳香族衍生物(图 3),其合成途径所用的催化酶大多数来源于其他物种。目前,已报道由DHS到儿茶酚有5条合成途径,然后儿茶酚在儿茶酚1, 2-氧化酶催化下生成顺, 顺-粘康酸[1, 53, 80-83]。但是研究较多、合成效率较高的是DHS—原儿茶酸—儿茶酚—顺, 顺-粘康酸途径,其顺, 顺-粘康酸产量最高达64.5 g/L。该途径中间产物原儿茶酸和儿茶酚细胞毒性较强,并且发酵液中有少量DHS和原儿茶酸残留,可能是因为原儿茶酸脱羧酶和儿茶酚1, 2-氧化酶的催化活性较低[30]。通过化学加氢方法,顺, 顺-粘康酸很容易转化为己二酸。利用生物酶催化法也有报道,但是酶催化活性很低,仅能催化0.7 mmol/L顺, 顺-粘康酸底物,转化率为91.1%[84]。DHS经分支酸可以进一步转化为对氨基苯甲酸,而对氨基苯甲酸是合成叶酸的前体物质[85]。大肠杆菌中含有叶酸合成途径,但是代谢流量很低。因此,构建对氨基苯甲酸生产菌株需要阻断芳香族氨基酸合成途径,提高相关酶催化活性。此外,DHS还可以转化为没食子酸[11]、香草醛[65]、苯酚[86]、3-氨基苯甲酸[87]、熊果苷[88]等多种芳香族化合物。

|

| 图 3 DHS衍生物的生物合成(3-脱氢莽草酸3-dehydroshikimate,莽草酸shikimate,3-脱氢奎尼酸3-dehydroquinate,奎尼酸quinic acid,原儿茶酸protocatechuic acid,原儿茶醛protocatechuic aldehyde,原儿茶醇protocatechuic alcohol,香草酸vanillic acid,香草醛vanillin,香草醇vanillyl alcohol,没食子酸gallic acid,焦性没食子酸pyrogallol,儿茶酚catechol,顺, 顺-粘康酸cis, cis-muconic acid,己二酸adipic acid,莽草酸3-磷酸shikimate 3-phosphate,5-烯醇丙酮酰莽草酸-3-磷酸5-enolpyruvylshikimate 3-phosphate,分支酸chorismate,4-羟基苯甲酸4-hydroxybenzoic acid,对苯二酚hydroquinone,熊果苷arbutin,邻氨基苯甲酸anthranilic acid,异分支酸isochorismate,水杨酸salicylic acid,苯酚phenol,2, 3-二羟基苯甲酸2, 3-dihydroxybenzoic acid,3-氨基苯甲酸3-aminobenzoic acid,4-氨基-4脱氧分支酸4-amino-4-deoxychorismate,对氨基苯甲酸p-aminobenzoic acid) Fig. 3 Biosynthesis of DHS derivatives from extended shikimate pathway. Genes and the enzymes they encode: ydiB: shikimate dehydrogenase/quinate dehydrogenase; aroD: 3-dehydroquinic acid dehydratase; aroE: shikimate dehydrogenase; aroK/aroL: shikimate kinase; aroA: 5-enolpyruvylshikimate 3-phosphate synthase; aroC: chorismate synthase; aroZ/qsuB/3dsd/asbF: 3-dehydroshikimate dehydratase; aroY/kpdBD: protocatechuate decarboxylase; catA: catechol 1, 2-dioxygenase; er: enoate reductase; sdh: shikimate dehydrogenases; pobA: 4-hydroxybenzoic acid hydrolyase; acar: aryl carboxylic acid reductase; comt: caffeate O-methyltransferase; adh: alcohol dehydrogenase; ubiC: chorismate lyase; mnx1: 4-hydroxybenzoate 1-hydroxylase; as: arbutin synthase; trpEG: anthranilate synthase; antABC: anthranilate 1, 2-dioxygenase; entC/menF: isochorismate synthase; entB: isochorismatase; pchB: isochorismate pyruvate lyase; nahG: salicylate 1-monoxygenase; sdc: salicylate decarboxylase; entA: 2, 3-dihydro-2, 3-dihydroxybenzoate dehydrogenase; entX: 2, 3-dihydroxybenzoate decarboxylase; pabAB: 4-amino-4-deoxychorismate synthase; pabC: 4-amino-4-deoxychorismate lyase; pctV: 3-aminobenzoic acid synthase. |

| 图选项 |

3.2 L-苯丙氨酸底盘细胞构建及其衍生物的生物合成L-苯丙氨酸是人体和动物不能靠自身合成的一种必需氨基酸,广泛应用于食品、饲料、医药等领域[1]。随着生物合成技术的日益发展,利用微生物发酵的方式生产L-苯丙氨酸逐渐成为主流生产方法。早在20世纪90年代初,研究人员在L-苯丙氨酸合成途径调控、发酵菌种的选育以及发酵条件优化等方面做了大量研究工作,发酵水平达到50 g/L左右[89-90]。进入21世纪以来,通过广大研究人员对L-苯丙氨酸合成途径进行不断地设计、改造与优化,将L-苯丙氨酸产量逐步提升至72.9 g/L [22]。这些工作的开展为L-苯丙氨酸衍生物的生物合成提供了坚实的工作基础。

以L-苯丙氨酸及其合成前体苯丙酮酸为中心可以转化为多种芳香族衍生物(图 4)。苯丙酮酸可以直接转化为D/L-苯乳酸[57, 74]、D-苯丙氨酸[91]、S-扁桃酸[92]等,也可以间接转化为下游D/L-苯甘氨酸[93-94]、R-扁桃酸[92]、2-苯乙醇[57]以及L-高苯丙氨酸[95-96]等,但是这些途径大多数是需要辅酶参与的异源合成途径,因此产量一般较低。以L-苯丙氨酸作为前体,通过构建辅酶循环再生体系,利用全细胞催化或体外酶催化的方式或许可以获得较高的产量或转化率。L-苯丙氨酸脱氨之后生成反式肉桂酸。反式肉桂酸也是一种重要的合成前体,可以直接转化为3-苯基丙酸[97]、苯乙烯[98],也可以经肉桂醛转化为肉桂醇[99]或经过肉桂酰辅酶A合成乔松素[100]、赤松素[101]等较复杂的芳香族化合物,还可以转化为对香豆酸[102]进入L-酪氨酸衍生物合成途径。L-苯丙氨酸在酪氨酸脱羧酶作用下转化为苯乙胺,与催化L-酪氨酸脱羧反应的脱羧酶相同[103]。L-苯丙氨酸是甜味剂阿斯巴甜的合成前体。目前未见从头合成阿斯巴甜的报道,但可以通过全细胞催化的方式实现从L-苯丙氨酸到阿斯巴甜的生物转化[104]。Luo等[75]尝试了两条不同的苯甲酸合成途径,一条是植物来源的以L-苯丙氨酸为前体,一条是微生物来源的以苯丙酮酸为前体,均实现了从葡萄糖到苯甲酸的从头合成,其中植物来源的合成途径虽然较长,但合成效率较高,苯甲酸产量大约是微生物来源合成途径的13倍。

|

| 图 4 L-苯丙氨酸衍生物的生物合成(苯丙酮酸phenylpyruvate,L-苯丙氨酸L-phenylalanine,D-苯丙氨酸D-phenylalanine,2-苄基丙二酸2-benzylmalonic acid,3-苄基丙二酸3-benzylmalonic acid,2-氧代苯基丁酸2-oxophenylbutyrate,L-高苯丙氨酸L-homophenylalanine,苯乙醛phenylacetaldehyde,2-苯乙醇2-phenylethanol,2-苯乙酸2-phenylacetic acid,D-苯乳酸D-phenyllactic acid,苯乙胺phenethylamine,反式肉桂酸trans-cinnamic acid,肉桂醛cinnamaldehyde,肉桂醇cinnamyl alcohol,肉桂酰辅酶A cinnamoyl-CoA,乔松素pinocembrin,赤松素pinosylvin,3-苯基丙酸3-phenylpropionic acid,苯乙烯styrene,对香豆酸p-coumeric acid,白藜芦醇trans-resveratrol,咖啡酸caffeic acid,4-羟基苯乙烯4-hydroxystyrene,阿斯巴甜aspartame,L-苯乳酸L-phenyllactic acid,S-扁桃酸S-mandelic acid,苯乙醛酸phenylglyoxylate,苯甲酸benzoic acid,R-扁桃酸R-mandelic acid,D-苯甘氨酸D-phenylglycine,L-苯甘氨酸L-phenylglycine,苯乙酰辅酶A phenylacetyl-CoA,苯甲酰辅酶A phenylformyl-CoA) Fig. 4 Biosynthesis of L-phenylalanine derivatives from extended L-phenylalanine pathway. Genes and the enzymes they encode: hphA: benzylmalate synthase; hphB: 3-benzylmalate dehydrogenase; hphCD: 3-benzylmalate isomerase; aro10/pdc/ipdC: phenylpyruvate decarboxylase; kdc: 2-keto acid decarboxylase; adh/yjgB: alcohol dehydrogenase; yqhD/yahK: aldehyde reductases; par: phenylacetaldehyde reductase; l-ldh/ldhA: L-lactate dehydrogenase; feaB: phenylacetaldehyde dehydrogenase; aldH: aldehyde dehydrogenase H; dat: D-amino acid aminotransferase; pglB: pyruvate dehydrogenase E1 component α-subunit; pglC: pyruvate dehydrogenase E1 component β-subunit; pglA: hydroxyacyl-dehydrogenase; pglD: thioesterase type Ⅱ; hmaS: L-4-hydroxymandelate synthase; hmo: L-4-hydroxymandelate oxidase; mdlB: S-mandelic acid dehydrogenase; hpgT: L-(4-hydroxy)phenylglycine transaminase; hpgAT: D-(4-hydroxy)phenylglycine aminotransferase; dmd: D-mandelate dehydrogenase; mdlC: phenylglyoxylate decarboxylase; mdlD: benzaldehyde dehydrogenase; tyrB/aro8/aro9: aromatic amino acid transaminase; tdc: tyrosine decarboxylase; aspC: aspartate aminotransferase; pal: phenylalanine ammonia lyase; pprA: phenylpyruvate reductase; acar: aryl carboxylic acid reductase; entD: phosphopantetheinyl transferase; 4cl: 4-coumarate: CoA ligase; ccr: cinnamoyl-CoA reductase; c4h: cinnamate 4-hydroxylase; cpr: cytochrome P450 reductase; fdc1: ferulate decarboxylase; pad1: phenylacrylic acid decarboxylase 1; 2er: 2-enoate reductase; sts: stylopine synthase; chs: chalcone synthase; chi: chalcone isomerase. |

| 图选项 |

3.3 L-酪氨酸底盘细胞的构建及其衍生物的生物合成L-酪氨酸是一种重要的营养必需氨基酸,广泛应用于食品、饲料、医药和化工等领域。通过敲除pheL和pheA,过表达tyrA,将高产L-苯丙氨酸菌株改造成L-酪氨酸生产菌株是一种简单、有效的构建方式。Patnaik等[32]将该策略与发酵条件优化相结合,成功将L-酪氨酸的产量提升至55 g/L。Kim等[23]增加L-酪氨酸合成途径关键基因aroGfbr、aroL、tyrC的表达量,敲除L-酪氨酸特异性转运蛋白基因tyrP,结合“DO-stat补料策略”,最终L-酪氨酸产量达到43.14 g/L。在高产L-酪氨酸细胞内整合内源或异源合成途径,可以获得不同L-酪氨酸衍生物的细胞工厂。

以L-酪氨酸及其合成前体4-羟基苯丙酮酸为中心可以转化为多种芳香族衍生物(图 5)。L-酪氨酸衍生物合成途径中许多酶的底物专一性较差,导致某一种产物具有多种合成途径,并且某些酶也能参与L-苯丙氨酸衍生物的合成。例如从4-羟基苯丙酮酸出发,羟基酪醇的合成途径可归纳为10余条(图 5)[1, 3, 13, 77]。但是受限于消耗大量辅酶、酶催化活性低以及产物毒性等原因,羟基酪醇的产量较低。蔡宇杰等[77]通过建立高效的辅酶循环再生体系,敲除酚类物质降解基因,强化表达合成途径相关基因,利用全细胞催化方式将200 g/L的左旋多巴转化为169.2 g/L的羟基酪醇,但是该方法只有在很高的细胞用量(200 g/L菌体湿重) 条件下才具有较好的催化效果。筛选具有更高催化活性的限速酶突变体(如HpaBC23F9-M4和TYOYM9-2) 有助于提高底物转化率[105],进一步降低全细胞催化反应的细胞用量。羟基酪醇合成前体酪醇可以与UDP-葡萄糖反应生成红景天苷和淫羊藿次甙D2[106]。此外,4-羟基苯丙酮酸通过羟化和加氢反应可以转化为丹参素[78],丹参素与咖啡酰辅酶A缩合生成迷迭香酸[107]。另一个重要的合成途径是L-酪氨酸脱氨生成对香豆酸,以对香豆酸为中心进一步转化为多种芳香族衍生物,如咖啡酸[108]、阿魏酸[109]、白藜芦醇[110]、3-(4-羟基苯基) 丙酸[97]等。催化L-酪氨酸转化为对香豆酸的酪氨酸解氨酶催化活性较低,并且对香豆酸具有较强的细胞毒性,因此如何解决上述问题成为提高对香豆酸及其衍生物产量的重要因素。L-酪氨酸在酪氨酸氨基变位酶催化作用下转化为(R)-β-酪氨酸。酪氨酸氨基变位酶的催化活性在植物和微生物中均有报道[111-112],但是尚未发现将其应用于合成(R)-β-酪氨酸的代谢工程研究。

|

| 图 5 L-酪氨酸衍生物的生物合成(4-羟基苯丙酮酸4-hydroxyphenylpyruvate,L-酪氨酸L-tyrosine,D-4-羟基苯乳酸D-4-hydroxyphenyllactic acid,丹参素salvianic acid A,咖啡酰辅酶A caffeoyl-CoA,迷迭香酸rosmarinic acid,3, 4-二羟基苯丙酮酸3, 4-dihydroxyphenylpyruvate,左旋多巴L-DOPA,多巴胺dopamine,3, 4-二羟基苯乙醛3, 4-dihydroxyphenylacetaldehyde,4-羟基苯乙醛4-hydroxyphenylacetaldehyde,酪醇tyrosol,羟基酪醇hydrotxytyrosol,UDP-葡萄糖UDP-glucose,红景天苷salidroside,淫羊藿次甙D2 icariside D2,4-羟基苯乙酸4-hydroxyphenylacetic acid,3, 4-二羟基苯乙酸3, 4-dihydroxyphenylacetic acid,(R)-β-酪氨酸(R)-β-tyrosine,苯酚phenol,酪胺tyramine,L-4-羟基扁桃酸L-4-hydroxymandelic acid,对香豆酸p-coumeric acid,白藜芦醇trans-resveratrol,咖啡酸caffeic acid,阿魏酸ferulic acid,4-羟基-3-甲氧基苯乙烯4-hydroxy-3-methoxystyrene,3, 4-二羟基苯乙烯3, 4-dihydroxystyrene,3-(4-羟基苯基)丙酸3-(4-hydroxyphenyl)propionic acid,4-羟基苯乙烯4-hydroxystyrene) Fig. 5 Biosynthesis of L-tyrosine derivatives from extended L-tyrosine pathway. Genes and the enzymes they encode: d-ldh: D-lactate dehydrogenase; hpaBC: 4-hydroxyphenylacetate 3-hydroxylase (a two component flavin-dependent monooxygenase); ras: rosmarinic acid synthase; ipdC/aro10: phenylpyruvate decarboxylase; kdc: 2-keto acid decarboxylase; adh/yjgB: alcohol dehydrogenase; yqhD/yahK: aldehyde reductase; ddc: L-dopa decarboxylase; tyo: tyramine oxidase; ugt: uridine diphosphate dependent glycosyltransferase; feaB: phenylacetaldehyde dehydrogenase; tyrB/aro8/aro9/aro: aromatic amino acid transaminase; aspC: aspartate aminotransferase; hmaS: L-4-hydroxymandelate synthase; aas: aromatic aldehyde synthase; tdc: tyrosine decarboxylase; tam: tyrosine aminomutase; tpl: tyrosine phenol lyase; tal: tyrosine ammonia-lyase; 2er: 2-enoate reductase; 4cl: 4-coumarate: CoA ligase; sts: stilbene synthase; sam5: 4-coumarate hydroxylase; pdc: p-coumaric acid decarboxylase; pad: phenolic acid decarboxylase; com: caffeic acid methyltransferase. |

| 图选项 |

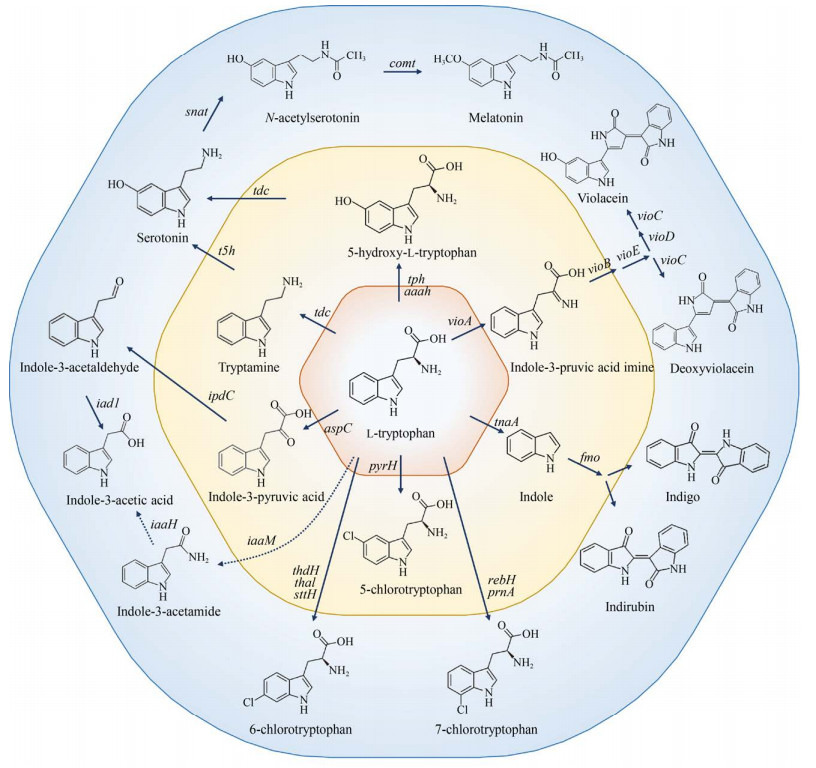

3.4 L-色氨酸底盘细胞构建及其衍生物的生物合成L-色氨酸作为人和动物体内的一种必需氨基酸,广泛应用于食品、药品、化工等领域,主要通过微生物发酵的方式进行生产。L-色氨酸生物合成是一个消耗能量和NADPH的过程,以PEP和E4P作为前体物质,还需要5-磷酸核糖-1-焦磷酸、L-谷氨酰胺、L-丝氨酸的参与。因此构建L-色氨酸高产菌株需要增加这些前体物质的供应,增加L-色氨酸向胞外转运。Shen等[113]敲除大肠杆菌trpR和tna,通过高拷贝质粒过表达aroGfbr、trpEfbr、serA,所得菌株通过分批补料发酵40 h可积累35.9 g/L的L-色氨酸;然后利用低拷贝质粒过表达tktA和ppsA,进一步增强E4P和PEP前体供应,L-色氨酸产量进一步提升至40.2 g/L。Wang等[24]系统分析了转运蛋白对L-色氨酸产量的影响,发现敲除mtr或过表达yddG或两者结合起来均可以提高L-色氨酸产量。副产物乙酸的生成也会影响L-色氨酸产量。Liu等[34]用磷酸乙酰转移酶突变体基因pta1替换大肠杆菌自身野生型pta,使得L-色氨酸产量提高了15%,乙酸减少了35%。

L-色氨酸经植物、动物和微生物细胞内代谢可以进一步转化为多种芳香族衍生物(图 6)。由于合成途径较长,大部分L-色氨酸衍生物从头合成的效率很低,主要通过催化转化的方式进行合成。Sun等[79]以高产L-色氨酸谷氨酸棒状杆菌为宿主细胞,通过质粒过表达异源vio基因簇,并对启动子和RBS类型、vio基因排列顺序、发酵工艺等条件进行系统代谢工程优化,最终菌株通过分批补料发酵合成5.436 g/L紫色杆菌素。L-色氨酸通过脱羧和羟化反应首先转化为血清素[114-115],然后血清素进一步转化为褪黑素[116],但是这些途径的微生物合成效率都比较低。Romasi和Lee [62]通过在大肠杆菌中表达L-色氨酸到吲哚-3-乙酸(生长素) 合成途径相关基因aspC、idpC、iad1,实现了L-色氨酸到吲哚-3-乙酸的高效催化转化,并且还检测到少量的色醇积累,但是未能鉴定出相关酶的表达基因。另一条经吲哚-3-乙胺到吲哚-3-乙酸的合成途径尚未发现代谢工程相关研究报道。L-色氨酸在色氨酸酶的作用下转化为吲哚,吲哚经黄素单加氧酶Fmo催化生成2-或3-羟基吲哚,然后通过自发二聚化生成靛红和靛蓝。Fmo的区域选择性受半胱氨酸的影响,添加少量半胱氨酸可以增加2-羟基吲哚的合成比例,有利于积累更多的靛红[117]。此外,L-色氨酸可以参与卤代反应,转化为5、6或7位的卤代产物[1, 118-120]。某些微生物尤其是海洋微生物中富含各种各样的卤代酶,但是相关卤代反应的催化效率仍然较低。利用上述卤代酶,Lee等[121]构建了分别表达Fre-SttH和TnaA以及Fmo的大肠杆菌,将L-色氨酸溴化和6-溴-色氨酸降解与6-溴-吲哚二聚化反应分隔开来,以L-色氨酸为底物合成天然色素6, 6′-二溴靛蓝。研究人员还测试了该体系同样适用于5和7位氯代或溴代色氨酸的不同色素催化合成。芳香族化合物的卤代反应为芳香族衍生物的生物合成打开了新的合成大门。

|

| 图 6 L-色氨酸衍生物的生物合成(L-色氨酸L-tryptophan,5-羟基-L-色氨酸5-hydroxy-L-tryptophan,色胺tryptamine,血清素serotonin,N-乙酰血清素N-acetylserotonin,褪黑素melatonin,吲哚-3-丙酮酸indole-3-pyruvic acid,吲哚-3-乙醛indole-3-acetaldehyde,吲哚-3-乙胺indole-3-acetamide,吲哚-3-乙酸indole-3-acetic acid,5/6/7-氯色氨酸5/6/7-chlorotryptophan,吲哚indole,靛蓝indigo,靛红indirubin,吲哚-3-丙酮酸亚胺indole-3-pruvic acid imine,紫色杆菌素violacein,脱氧紫色杆菌素deoxyviolacein) Fig. 6 Biosynthesis of L-tryptophan derivatives from extended L-tryptophan pathway. Genes and the enzymes they encode: tph: tryptophan hydroxylase; aaah: aromatic amino acid hydroxylase; tdc: tryptophan decarboxylase; t5h: tryptamine 5-hydroxylase; snat: serotonin N-acetyltransferase; comt: caffeic acid O-methyltransferase; vioA: L-amino acid oxidase; vioB: iminophenyl-pyruvate dimer synthase; vioC: monooxygenase; vioD: tryptophan hydroxylase; vioE: violacein biosynthesis protein; tnaA: tryptophanase; fmo: flavin-containing monooxygenase; aspC: aspartate aminotransferase; ipdC: indole-3-pyruvic acid decarboxylase; iad1: indole-3-acetic acid dehydrogenase; iaaM: tryptophan 2-monooxygenase; iaaH: indole-3-acetamide hydrolase; pyrH: tryptophan 5-halogenase; thdH/thal/sttH: tryptophan 6-halogenase; rebH/prnA: tryptophan 7-halogenase. |

| 图选项 |

4 总结与展望芳香族化合物广泛应用于医药、化工、食品和饲料等领域,市场前景广阔。通过代谢工程对芳香族化合物的合成途径进行理性设计与改造,使微生物细胞定向地大量积累人们需要的各种芳香族化合物。这些研究对解决化石能源危机和环境可持续发展问题具有积极意义。但是,目前只有少数芳香族化合物实现了高效的工业化发酵生产,大部分芳香族化合物的合成效率仍然较低。一方面通过代谢工程手段,例如代谢途径理性设计改造、辅因子工程、酶定向进化、适应性进化、高通量筛选等技术,对宿主细胞进行系统改造,提升发酵生产菌种的鲁棒性。另一方面,通过设计新的反应途径,表达异源合成途径相关基因,拓宽微生物合成芳香族化合物的产物谱,获得某些具有重要应用价值的新型芳香族化合物。我们相信,随着代谢工程技术的不断发展,越来越多的芳香族化合物将在微生物细胞中实现高效生物合成。

参考文献

| [1] | Wu FL, Cao P, Song GT, et al. Expanding the repertoire of aromatic chemicals by microbial production. J Chem Technol Biot, 2018, 93(10): 2804-2816. DOI:10.1002/jctb.5690 |

| [2] | Thompson B, Machas M, Nielsen DR. Creating pathways towards aromatic building blocks and fine chemicals. Curr Opin Biotechnol, 2015, 36: 1-7. |

| [3] | Shen YP, Niu FX, Yan ZB, et al. Recent advances in metabolically engineered microorganisms for the production of aromatic chemicals derived from aromatic amino acids. Front Bioeng Biotechnol, 2020, 8: 407. DOI:10.3389/fbioe.2020.00407 |

| [4] | 吴凤礼, 彭彦峰, 徐毅诚, 等. 代谢工程改造微生物生产芳香族化合物的研究进展. 生物加工过程, 2017, 15(5): 9-23. Wu FL, Peng YF, Xu YC, et al. Advances in microbial metabolic engineering for producing aromatic chemicals. Chin J Bioproc Eng, 2017, 15(5): 9-23 (in Chinese). |

| [5] | Jiang M, Zhang HR. Engineering the shikimate pathway for biosynthesis of molecules with pharmaceutical activities in E. coli. Curr Opin Biotechnol, 2016, 42: 1-6. |

| [6] | Kohlstedt M, Starck S, Barton N, et al. From lignin to nylon: Cascaded chemical and biochemical conversion using metabolically engineered Pseudomonas putida. Metab Eng, 2018, 47: 279-293. DOI:10.1016/j.ymben.2018.03.003 |

| [7] | Cai CG, Xu ZX, Xu ML, et al. Development of a Rhodococcus opacus cell factory for valorizing lignin to muconate. ACS Sustainable Chem Eng, 2020, 8(4): 2016-2031. DOI:10.1021/acssuschemeng.9b06571 |

| [8] | Banerjee R, Mukherjee G, Patra KC. Microbial transformation of tannin-rich substrate to gallic acid through co-culture method. Bioresour Technol, 2005, 96(8): 949-953. DOI:10.1016/j.biortech.2004.08.004 |

| [9] | Leighty RW, Antoniewicz MR. COMPLETE-MFA: complementary parallel labeling experiments technique for metabolic flux analysis. Metab Eng, 2013, 20: 49-55. DOI:10.1016/j.ymben.2013.08.006 |

| [10] | Abatemarco J, Sarhan MF, Wagner JM, et al. RNA-aptamers-in-droplets (RAPID) high-throughput screening for secretory phenotypes. Nat Commun, 2017, 8(1): 332. DOI:10.1038/s41467-017-00425-7 |

| [11] | Chen ZY, Shen XL, Wang J, et al. Rational engineering of p-hydroxybenzoate hydroxylase to enable efficient gallic acid synthesis via a novel artificial biosynthetic pathway. Biotechnol Bioeng, 2017, 114(11): 2571-2580. DOI:10.1002/bit.26364 |

| [12] | Shen XL, Wang J, Li CY, et al. Dynamic gene expression engineering as a tool in pathway engineering. Curr Opin Biotechnol, 2019, 59: 122-129. DOI:10.1016/j.copbio.2019.03.019 |

| [13] | Chen W, Yao J, Meng J, et al. Promiscuous enzymatic activity-aided multiple-pathway network design for metabolic flux rearrangement in hydroxytyrosol biosynthesis. Nat Commun, 2019, 10: 960. DOI:10.1038/s41467-019-08781-2 |

| [14] | 鄢芳清, 韩亚昆, 李娟, 等. 大肠杆菌芳香族氨基酸代谢工程研究进展. 生物加工过程, 2017, 15(5): 32-39, 85. Yan FQ, Han YK, Li J, et al. Metabolic engineering of aromatic amino acids in Escherichia coli. Chin J Bioproc Eng, 2017, 15(5): 32-39, 85 (in Chinese). |

| [15] | Flores N, Xiao J, Berry A, et al. Pathway engineering for the production of aromatic compounds in Escherichia coli. Nat Biotechnol, 1996, 14(5): 620-623. DOI:10.1038/nbt0596-620 |

| [16] | Yi J, Draths KM, Li K, et al. Altered glucose transport and shikimate pathway product yields in E. coli. Biotechnol Prog, 2003, 19(5): 1450-1459. DOI:10.1021/bp0340584 |

| [17] | Hernández-Montalvo V, Martínez A, Hernández-Chavez G, et al. Expression of galP and glk in a Escherichia coli PTS mutant restores glucose transport and increases glycolytic flux to fermentation products. Biotechnol Bioeng, 2003, 83(6): 687-694. DOI:10.1002/bit.10702 |

| [18] | Li K, Mikola MR, Draths KM, et al. Fed-batch fermentor synthesis of 3-dehydroshikimic acid using recombinant Escherichia coli. Biotechnol Bioeng, 1999, 64(1): 61-73. DOI:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0290(19990705)64:1<61::AID-BIT7>3.0.CO;2-G |

| [19] | Bongaerts J, Kr?mer M, Müller U, et al. Metabolic engineering for microbial production of aromatic amino acids and derived compounds. Metab Eng, 2001, 3(4): 289-300. DOI:10.1006/mben.2001.0196 |

| [20] | Ger YM, Chen SL, Chiang HJ, et al. A single Ser-180 mutation desensitizes feedback inhibition of the phenylalanine-sensitive 3-deoxy-D-arabino- heptulosonate 7-phosphate (DAHP) synthetase in Escherichia coli. J Biochem, 1994, 116(5): 986-990. DOI:10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a124657 |

| [21] | Liu SP, Xiao MR, Zhang L, et al. Production of L-phenylalanine from glucose by metabolic engineering of wild type Escherichia coli W3110. Process Biochem, 2013, 48(3): 413-419. DOI:10.1016/j.procbio.2013.02.016 |

| [22] | Liu YF, Xu YR, Ding DQ, et al. Genetic engineering of Escherichia coli to improve L-phenylalanine production. BMC Biotechnol, 2018, 18(1): 5. DOI:10.1186/s12896-018-0418-1 |

| [23] | Kim B, Binkley R, Kim HU, et al. Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli for the enhanced production of L-tyrosine. Biotechnol Bioeng, 2018, 115(10): 2554-2564. DOI:10.1002/bit.26797 |

| [24] | Wang J, Cheng LK, Wang J, et al. Genetic engineering of Escherichia coli to enhance production of L-tryptophan. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol, 2013, 97(17): 7587-7596. DOI:10.1007/s00253-013-5026-3 |

| [25] | Chen L, Zeng AP. Rational design and metabolic analysis of Escherichia coli for effective production of L-tryptophan at high concentration. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol, 2017, 101(2): 559-568. DOI:10.1007/s00253-016-7772-5 |

| [26] | Pittard J, Camakaris H, Yang J. The TyrR regulon. Mol Microbiol, 2005, 55(1): 16-26. |

| [27] | Chen YY, Liu YF, Ding DQ, et al. Rational design and analysis of an Escherichia coli strain for high-efficiency tryptophan production. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol, 2018, 45(5): 357-367. DOI:10.1007/s10295-018-2020-x |

| [28] | Long CP, Gonzalez JE, Feist AM, et al. Fast growth phenotype of E. coli K-12 from adaptive laboratory evolution does not require intracellular flux rewiring. Metab Eng, 2017, 44: 100-107. DOI:10.1016/j.ymben.2017.09.012 |

| [29] | Rodriguez A, Martínez JA, Báez-Viveros JL, et al. Constitutive expression of selected genes from the pentose phosphate and aromatic pathways increases the shikimic acid yield in high-glucose batch cultures of an Escherichia coli strain lacking PTS and pykF. Microb Cell Fact, 2013, 12: 86. DOI:10.1186/1475-2859-12-86 |

| [30] | Choi SS, Seo SY, Park SO, et al. Cell factory design and culture process optimization for dehydroshikimate biosynthesis in Escherichia coli. Front Bioeng Biotechnol, 2019, 7: 241. DOI:10.3389/fbioe.2019.00241 |

| [31] | Liu SP, Liu RX, Xiao MR, et al. A systems level engineered E. coli capable of efficiently producing L-phenylalanine. Process Biochem, 2014, 49(5): 751-757. DOI:10.1016/j.procbio.2014.01.001 |

| [32] | Patnaik R, Zolandz RR, Green DA, et al. L-tyrosine production by recombinant Escherichia coli: fermentation optimization and recovery. Biotechnol Bioeng, 2008, 99(4): 741-752. DOI:10.1002/bit.21765 |

| [33] | Santos CNS, Xiao WH, Stephanopoulos G. Rational, combinatorial, and genomic approaches for engineering L-tyrosine production in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2012, 109(34): 13538-13543. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1206346109 |

| [34] | Liu LN, Duan XG, Wu J. L-tryptophan production in Escherichia coli improved by weakening the Pta-AckA pathway. PLoS ONE, 2016, 11(6): e0158200. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0158200 |

| [35] | Yi J, Li K, Draths KM, et al. Modulation of phosphoenolpyruvate synthase expression increases shikimate pathway product yields in E. coli. Biotechnol Prog, 2002, 18(6): 1141-1148. DOI:10.1021/bp020101w |

| [36] | 马延和, 王钦宏, 陈五九, 等. 生产3-脱氢莽草酸大肠杆菌重组菌株及其构建方法与应用: CN, 201711002831.2. 2017-10-24. M a YH, Wang QH, Chen WJ, et al. Escherichia coli recombinant bacterial strain for producing 3-dehydroshikimic acid as well as establishment method and application thereof: CN, 201711002831.2. 2017-10-24 (in Chinese). |

| [37] | Gu PF, Yang F, Kang JH, et al. One-step of tryptophan attenuator inactivation and promoter swapping to improve the production of L-tryptophan in Escherichia coli. Microb Cell Fact, 2012, 11: 30. DOI:10.1186/1475-2859-11-30 |

| [38] | Liu Q, Cheng YS, Xie XX, et al. Modification of tryptophan transport system and its impact on production of L-tryptophan in Escherichia coli. Bioresour Technol, 2012, 114: 549-554. DOI:10.1016/j.biortech.2012.02.088 |

| [39] | Gu PF, Yang F, Li FF, et al. Knocking out analysis of tryptophan permeases in Escherichia coli for improving L-tryptophan production. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol, 2013, 97(15): 6677-6683. DOI:10.1007/s00253-013-4988-5 |

| [40] | Doroshenko V, Airich L, Vitushkina M, et al. YddG from Escherichia coli promotes export of aromatic amino acids. FEMS Microbiol Lett, 2007, 275(2): 312-318. DOI:10.1111/j.1574-6968.2007.00894.x |

| [41] | Li LP, Tu R, Song GT, et al. Development of a synthetic 3-dehydroshikimate biosensor in Escherichia coli for metabolite monitoring and genetic screening. ACS Synth Biol, 2019, 8(2): 297-306. DOI:10.1021/acssynbio.8b00317 |

| [42] | Tu R, Li LP, Yuan HL, et al. Biosensor-enabled droplet microfluidic system for the rapid screening of 3-dehydroshikimic acid produced in Escherichia coli. J Ind Microbiol Biotechnol, 2020. DOI:10.1007/s10295-020-02316-1 |

| [43] | Liu C, Zhang B, Liu YM, et al. New intracellular shikimic acid biosensor for monitoring shikimate synthesis in Corynebacterium glutamicum. ACS Synth Biol, 2018, 7(2): 591-601. DOI:10.1021/acssynbio.7b00339 |

| [44] | Liu YF, Zhuang YY, Ding DQ, et al. Biosensor-based evolution and elucidation of a biosynthetic pathway in Escherichia coli. ACS Synth Biol, 2017, 6(5): 837-848. DOI:10.1021/acssynbio.6b00328 |

| [45] | Siedler S, Khatri NK, Zsohar A, et al. Development of a bacterial biosensor for rapid screening of Yeast p-coumaric acid production. ACS Synth Biol, 2017, 6(10): 1860-1869. DOI:10.1021/acssynbio.7b00009 |

| [46] | Chen JX, Steel H, Wu YH, et al. Development of aspirin-inducible biosensors in Escherichia coli and SimCells. Appl Environ Microbiol, 2019, 85(6): e02959-18. |

| [47] | Ding DQ, Li JL, Bai DY, et al. Biosensor-based monitoring of the central metabolic pathway metabolites. Biosens Bioelectron, 2020, 167: 112456. DOI:10.1016/j.bios.2020.112456 |

| [48] | Santos CN, Stephanopoulos G. Melanin-based high-throughput screen for L-tyrosine production in Escherichia coli. Appl Environ Microbiol, 2008, 74(4): 1190-1197. DOI:10.1128/AEM.02448-07 |

| [49] | 霍亚楠, 吴凤礼, 宋国田, 等. 定向进化改造酪氨酸解氨酶提高大肠杆菌合成对香豆酸产量. 生物工程学报, 2020, 36(11): 2367-2376. Huo YN, Wu FL, Song GT, et al. Directed evolution of tyrosine ammonia-lyase to improve the production of p-coumaric acid in Escherichia coli. Chin J Biotech, 2020, 36(11): 2367-2376 (in Chinese). |

| [50] | Kramer L, Le X, Rodriguez M, et al. Engineering carboxylic acid reductase (CAR) through a whole-cell growth-coupled NADPH recycling strategy. ACS Synth Biol, 2020, 9(7): 1632-1637. DOI:10.1021/acssynbio.0c00290 |

| [51] | Lu J, Tang JL, Liu Y, et al. Combinatorial modulation of galP and glk gene expression for improved alternative glucose utilization. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol, 2012, 93(6): 2455-2462. DOI:10.1007/s00253-011-3752-y |

| [52] | Kim SC, Min BE, Hwang HG, et al. Pathway optimization by re-design of untranslated regions for L-tyrosine production in Escherichia coli. Sci Rep, 2015, 5: 13853. DOI:10.1038/srep13853 |

| [53] | Lin YH, Sun XX, Yuan QP, et al. Extending shikimate pathway for the production of muconic acid and its precursor salicylic acid in Escherichia coli. Metab Eng, 2014, 23: 62-69. DOI:10.1016/j.ymben.2014.02.009 |

| [54] | Maeda H, Dudareva N. The shikimate pathway and aromatic amino Acid biosynthesis in plants. Annu Rev Plant Biol, 2012, 63: 73-105. DOI:10.1146/annurev-arplant-042811-105439 |

| [55] | Kogure T, Kubota T, Suda M, et al. Metabolic engineering of Corynebacterium glutamicum for shikimate overproduction by growth-arrested cell reaction. Metab Eng, 2016, 38: 204-216. DOI:10.1016/j.ymben.2016.08.005 |

| [56] | Cui YY, Ling C, Zhang YY, et al. Production of shikimic acid from Escherichia coli through chemically inducible chromosomal evolution and cofactor metabolic engineering. Microb Cell Fact, 2014, 13: 21. DOI:10.1186/1475-2859-13-21 |

| [57] | Wang PC, Yang XW, Lin BX, et al. Cofactor self-sufficient whole-cell biocatalysts for the production of 2-phenylethanol. Metab Eng, 2017, 44: 143-149. DOI:10.1016/j.ymben.2017.09.013 |

| [58] | Sandberg TE, Salazar MJ, Weng LL, et al. The emergence of adaptive laboratory evolution as an efficient tool for biological discovery and industrial biotechnology. Metab Eng, 2019, 56: 1-16. DOI:10.1016/j.ymben.2019.08.004 |

| [59] | Kr?mer JO, Nunez-Bernal D, Averesch NJ, et al. Production of aromatics in Saccharomyces cerevisiae — a feasibility study. J Biotechnol, 2013, 163(2): 184-193. DOI:10.1016/j.jbiotec.2012.04.014 |

| [60] | Kambourakis S, Draths KM, Frost JW. Synthesis of gallic acid and pyrogallol from glucose: Replacing natural product isolation with microbial catalysis. J Am Chem Soc, 2000, 122(37): 9042-9043. DOI:10.1021/ja000853r |

| [61] | 王钦宏, 陈五九, 江小龙, 等. 一株生产原儿茶酸的大肠杆菌基因工程菌及其构建方法与应用: 中国, 201711390790.9. 2017-12-21. Wang QH, Chen WJ, Jiang XL, et al. Escherichia coli genetically-engineered bacterium for producing protocatechuic acid and construction method and application of Escherichia coli genetically-engineered bacterium: CN, 201711390790.9. 2017-12-21 (in Chinese). |

| [62] | Romasi EF, Lee J. Development of indole-3-acetic acid-producing Escherichia coli by functional expression of IpdC, AspC, and Iad1. J Microbiol Biotechnol, 2013, 23(12): 1726-1736. DOI:10.4014/jmb.1308.08082 |

| [63] | Strohmeier GA, Eitelj?rg IC, Schwarz A, et al. Enzymatic one-step reduction of carboxylates to aldehydes with cell-free regeneration of ATP and NADPH. Chemistry, 2019, 25(24): 6119-6123. DOI:10.1002/chem.201901147 |

| [64] | Kubota T, Watanabe A, Suda M, et al. Production of para-aminobenzoate by genetically engineered Corynebacterium glutamicum and non-biological formation of an N-glucosyl byproduct. Metab Eng, 2016, 38: 322-330. DOI:10.1016/j.ymben.2016.07.010 |

| [65] | Hansen EH, M?ller BL, Kock GR, et al. De novo biosynthesis of vanillin in fission yeast (Schizosaccharomyces pombe) and baker's yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae). Appl Environ Microbiol, 2009, 75(9): 2765-2774. DOI:10.1128/AEM.02681-08 |

| [66] | Kim B, Park H, Na D, et al. Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli for the production of phenol from glucose. Biotechnol J, 2014, 9(5): 621-629. DOI:10.1002/biot.201300263 |

| [67] | Kim B, Cho BR, Hahn JS. Metabolic engineering of Saccharomyces cerevisiae for the production of 2-phenylethanol via Ehrlich pathway. Biotechnol Bioeng, 2014, 111(1): 115-124. DOI:10.1002/bit.24993 |

| [68] | Chreptowicz K, Mierzejewska J. Enhanced bioproduction of 2-phenylethanol in a biphasic system with rapeseed oil. New Biotechnol, 2018, 42: 56-61. DOI:10.1016/j.nbt.2018.02.009 |

| [69] | Yang YP, Lin YH, Wang J, et al. Sensor-regulator and RNAi based bifunctional dynamic control network for engineered microbial synthesis. Nat Commun, 2018, 9(1): 3043. DOI:10.1038/s41467-018-05466-0 |

| [70] | Wu J, Liu YF, Zhao S, et al. Application of dynamic regulation to increase L-phenylalanine production in Escherichia coli. J Microbiol Biotechnol, 2019, 29(6): 923-932. DOI:10.4014/jmb.1901.01058 |

| [71] | Patnaik R, Spitzer RG, Liao JC. Pathway engineering for production of aromatics in Escherichia coli: confirmation of stoichiometric analysis by independent modulation of AroG, TktA, and Pps activities. Biotechnol Bioeng, 1995, 46(4): 361-370. DOI:10.1002/bit.260460409 |

| [72] | Chandran SS, Yi J, Draths KM, et al. Phosphoenolpyruvate availability and the biosynthesis of shikimic acid. Biotechnol Prog, 2003, 19(3): 808-814. DOI:10.1021/bp025769p |

| [73] | Kogure T, Suda M, Hiraga K, et al. Protocatechuate overproduction by Corynebacterium glutamicum via simultaneous engineering of native and heterologous biosynthetic pathways. Metab Eng, 2020. DOI:10.1016/j.ymben.2020.11.007 |

| [74] | Fujita T, Nguyen HD, Ito T, et al. Microbial monomers custom-synthesized to build true bio-derived aromatic polymers. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol, 2013, 97(20): 8887-8894. DOI:10.1007/s00253-013-5078-4 |

| [75] | Luo ZW, Lee SY. Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli for the production of benzoic acid from glucose. Metab Eng, 2020, 62: 298-311. DOI:10.1016/j.ymben.2020.10.002 |

| [76] | 马延和, 王钦宏, 陈五九, 等. 生产左旋多巴大肠杆菌重组菌株及其构建方法与应用: 中国, 201711003046.9. 2017-10-24. Ma YH, Wang QH, Chen WJ, et al. Recombinant strain for producing levodopa Escherichia coli as well as construction method and application thereof: CN, 201711003046.9. 2017-10-24 (in Chinese). |

| [77] | 蔡宇杰, 刘金彬, 李朝智, 等. 一种生产羟基酪醇的方法: 中国, 201811234787.2. 2018-10-23. Cai YJ, Liu JB, Li CZ, et al. Method for producing hydroxytyrosol: CN, 201811234787.2. 2018-10-23 (in Chinese). |

| [78] | Yao YF, Wang CS, Qiao JJ, et al. Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli for production of salvianic acid A via an artificial biosynthetic pathway. Metab Eng, 2013, 19: 79-87. DOI:10.1016/j.ymben.2013.06.001 |

| [79] | Sun HN, Zhao DD, Xiong B, et al. Engineering Corynebacterium glutamicum for violacein hyper production. Microb Cell Fact, 2016, 15: 148. DOI:10.1186/s12934-016-0545-0 |

| [80] | Niu W, Draths KM, Frost JW. Benzene-free synthesis of adipic acid. Biotechnol Prog, 2002, 18(2): 201-211. DOI:10.1021/bp010179x |

| [81] | Sun XX, Lin YH, Huang Q, et al. A novel muconic acid biosynthesis approach by shunting tryptophan biosynthesis via anthranilate. Appl Environ Microbiol, 2013, 79(13): 4024-4030. DOI:10.1128/AEM.00859-13 |

| [82] | Sun XX, Lin YH, Yuan QP, et al. Biological production of muconic acid via a prokaryotic 2, 3-dihydroxybenzoic acid decarboxylase. Chem Sus Chem, 2014, 7(9): 2478-2481. DOI:10.1002/cssc.201402092 |

| [83] | Sengupta S, Jonnalagadda S, Goonewardena L, et al. Metabolic engineering of a novel muconic acid biosynthesis pathway via 4-hydroxybenzoic acid in Escherichia coli. Appl Environ Microbiol, 2015, 81(23): 8037-8043. DOI:10.1128/AEM.01386-15 |

| [84] | Joo JC, Khusnutdinova AN, Flick R, et al. Alkene hydrogenation activity of enoate reductases for an environmentally benign biosynthesis of adipic acid. Chem Sci, 2017, 8(2): 1406-1413. DOI:10.1039/C6SC02842J |

| [85] | Koma D, Yamanaka H, Moriyoshi K, et al. Production of p-aminobenzoic acid by metabolically engineered Escherichia coli. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem, 2014, 78(2): 350-357. DOI:10.1080/09168451.2014.878222 |

| [86] | Thompson B, Machas M, Nielsen DR. Engineering and comparison of non-natural pathways for microbial phenol production. Biotechnol Bioeng, 2016, 113(8): 1745-1754. DOI:10.1002/bit.25942 |

| [87] | Hirayama A, Eguchi T, Kudo F. A single PLP-dependent enzyme PctV catalyzes the transformation of 3-dehydroshikimate into 3-aminobenzoate in the biosynthesis of pactamycin. Chem Bio Chem, 2013, 14(10): 1198-1203. DOI:10.1002/cbic.201300153 |

| [88] | Shen XL, Wang J, Wang J, et al. High-level de novo biosynthesis of arbutin in engineered Escherichia coli. Metab Eng, 2017, 42: 52-58. DOI:10.1016/j.ymben.2017.06.001 |

| [89] | Backman K, O'Connor MJ, Maruya A, et al. Genetic engineering of metabolic pathways applied to the production of phenylalanine. Ann N Y Acad Sci, 1990, 589(1): 16-24. |

| [90] | Konstantinov KB, Nishio N, Seki T, et al. Physiologically motivated strategies for control of the fed-batch cultivation of recombinant Escherichia coli for phenylalanine production. J Ferment Bioeng, 1991, 71(5): 350-355. DOI:10.1016/0922-338X(91)90349-L |

| [91] | Liu RX, Liu SP, Cheng S, et al. Screening, characterization and utilization of D-amino acid aminotransferase to obtain D-phenylalanine. Appl Biochem Microbiol, 2015, 51(6): 695-703. DOI:10.1134/S0003683815060095 |

| [92] | Sun ZT, Ning YY, Liu LX, et al. Metabolic engineering of the L-phenylalanine pathway in Escherichia coli for the production of S- or R-mandelic acid. Microb Cell Fact, 2011, 10: 71. DOI:10.1186/1475-2859-10-71 |

| [93] | Müller U, Van Assema F, Gunsior M, et al. Metabolic engineering of the E. coli L-phenylalanine pathway for the production of D-phenylglycine (D-Phg). Metab Eng, 2006, 8(3): 196-208. DOI:10.1016/j.ymben.2005.12.001 |

| [94] | Liu SP, Liu RX, El-Rotail AAMM, et al. Heterologous pathway for the production of L-phenylglycine from glucose by E. coli. J Biotechnol, 2014, 186: 91-97. DOI:10.1016/j.jbiotec.2014.06.033 |

| [95] | Koketsu K, Mitsuhashi S, Tabata K. Identification of homophenylalanine biosynthetic genes from the cyanobacterium Nostoc punctiforme PCC73102 and application to its microbial production by Escherichia coli. Appl Environ Microbiol, 2013, 79(7): 2201-2208. DOI:10.1128/AEM.03596-12 |

| [96] | Liu ZN, Lei DW, Qiao B, et al. Integrative biosynthetic gene cluster mining to optimize a metabolic pathway to efficiently produce L-homophenylalanine in Escherichia coli. ACS Synth Biol, 2020, 9(11): 2943-2954. DOI:10.1021/acssynbio.0c00363 |

| [97] | Sun J, Lin YH, Shen XL, et al. Aerobic biosynthesis of hydrocinnamic acids in Escherichia coli with a strictly oxygen-sensitive enoate reductase. Metab Eng, 2016, 35: 75-82. DOI:10.1016/j.ymben.2016.02.002 |

| [98] | McKenna R, Nielsen DR. Styrene biosynthesis from glucose by engineered E. coli. Metab Eng, 2011, 13(5): 544-554. DOI:10.1016/j.ymben.2011.06.005 |

| [99] | Zhou W, Bi HP, Zhuang YB, et al. Production of cinnamyl alcohol glucoside from glucose in Escherichia coli. J Agric Food Chem, 2017, 65(10): 2129-2135. DOI:10.1021/acs.jafc.7b00076 |

| [100] | Leonard E, Lim KH, Saw PN, et al. Engineering central metabolic pathways for high-level flavonoid production in Escherichia coli. Appl Environ Microbiol, 2007, 73(12): 3877-3886. DOI:10.1128/AEM.00200-07 |

| [101] | Wu JJ, Zhang X, Zhu YJ, et al. Rational modular design of metabolic network for efficient production of plant polyphenol pinosylvin. Sci Rep, 2017, 7: 1459. DOI:10.1038/s41598-017-01700-9 |

| [102] | Liu XN, Cheng J, Zhang GH, et al. Engineering yeast for the production of breviscapine by genomic analysis and synthetic biology approaches. Nat Commun, 2018, 9: 448. DOI:10.1038/s41467-018-02883-z |

| [103] | Marcobal A, De Las Rivas B, Landete JM, et al. Tyramine and phenylethylamine biosynthesis by food bacteria. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr, 2012, 52(5): 448-467. DOI:10.1080/10408398.2010.500545 |

| [104] | 徐堃, 顾汉章, 刘龙, 等. 一种采用全细胞转化生产阿斯巴甜的方法: 中国, 201710391200.8. 2017-05-27. Xu K, Gu HZ, Liu L, et al. Method of producing aspartame by means of whole cell conversion: CN, 201710391200.8. 2017-05-27 (in Chinese). |

| [105] | Yao J, He Y, Su NN, et al. Developing a highly efficient hydroxytyrosol whole-cell catalyst by de-bottlenecking rate-limiting steps. Nat Commun, 2020, 11: 1515. DOI:10.1038/s41467-020-14918-5 |

| [106] | Bai YF, Bi HP, Zhuang YB, et al. Production of salidroside in metabolically engineered Escherichia coli. Sci Rep, 2014, 4: 6640. |

| [107] | Babaei M, Zamfir GMB, Chen X, et al. Metabolic engineering of Saccharomyces cerevisiae for Rosmarinic Acid Production. ACS Synth Biol, 2020, 9(8): 1978-1988. DOI:10.1021/acssynbio.0c00048 |

| [108] | Huang Q, Lin YH, Yan YJ. Caffeic acid production enhancement by engineering a phenylalanine over-producing Escherichia coli strain. Biotechnol Bioeng, 2013, 110(12): 3188-3196. DOI:10.1002/bit.24988 |

| [109] | Kang SY, Choi O, Lee JK, et al. Artificial biosynthesis of phenylpropanoic acids in a tyrosine overproducing Escherichia coli strain. Microb Cell Fact, 2012, 11: 153. DOI:10.1186/1475-2859-11-153 |

| [110] | Lim CG, Fowler ZL, Hueller T, et al. High-yield resveratrol production in engineered Escherichia coli. Appl Environ Microbiol, 2011, 77(10): 3451-3460. DOI:10.1128/AEM.02186-10 |

| [111] | Yan J, Aboshi T, Teraishi M, et al. The tyrosine aminomutase TAM1 is required for β-tyrosine biosynthesis in rice. Plant Cell, 2015, 27(4): 1265-1278. DOI:10.1105/tpc.15.00058 |

| [112] | Wanninayake U, Walker KD. A bacterial tyrosine aminomutase proceeds through retention or inversion of stereochemistry to catalyze its isomerization reaction. J Am Chem Soc, 2013, 135(30): 11193-11204. DOI:10.1021/ja403918w |

| [113] | Shen T, Liu Q, Xie XX, et al. Improved production of tryptophan in genetically engineered Escherichia coli with TktA and PpsA overexpression. J Biomed Biotechnol, 2012, 2012: 605219. |

| [114] | Park S, Kang K, Lee SW, et al. Production of serotonin by dual expression of tryptophan decarboxylase and tryptamine 5-hydroxylase in Escherichia coli. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol, 2011, 89(5): 1387-1394. DOI:10.1007/s00253-010-2994-4 |

| [115] | Mora-Villalobos JA, Zeng AP. Synthetic pathways and processes for effective production of 5-hydroxytryptophan and serotonin from glucose in Escherichia coli. J Biol Eng, 2018, 12: 3. DOI:10.1186/s13036-018-0094-7 |

| [116] | Byeon Y, Back K. Melatonin production in Escherichia coli by dual expression of serotonin N-acetyltransferase and caffeic acid O-methyltransferase. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol, 2016, 100(15): 6683-6691. DOI:10.1007/s00253-016-7458-z |

| [117] | Han GH, Gim GH, Kim W, et al. Enhanced indirubin production in recombinant Escherichia coli harboring a flavin-containing monooxygenase gene by cysteine supplementation. J Biotechnol, 2012, 164(2): 179-187. |

| [118] | Zehner S, Kotzsch A, Bister B, et al. A regioselective tryptophan 5-halogenase is involved in pyrroindomycin biosynthesis in Streptomyces rugosporus LL-42D005. Chem Biol, 2005, 12(4): 445-452. DOI:10.1016/j.chembiol.2005.02.005 |

| [119] | Milbredt D, Patallo EP, Van Pee KH. A tryptophan 6-halogenase and an amidotransferase are involved in thienodolin biosynthesis. Chem Bio Chem, 2014, 15(7): 1011-1020. DOI:10.1002/cbic.201400016 |

| [120] | Bitto E, Huang Y, Bingman CA, et al. The structure of flavin-dependent tryptophan 7-halogenase RebH. Proteins, 2008, 70(1): 289-293. |

| [121] | Lee J, Kim J, Song JE, et al. Production of tyrian purple indigoid dye from tryptophan in Escherichia coli. Nat Chem Biol, 2021, 17(1): 104-112. DOI:10.1038/s41589-020-00684-4 |