1西南大学心理学部, 重庆 400715

2西南大学认知与人格教育部重点实验室, 重庆 400715

3华中师范大学心理学院, 武汉 430079

收稿日期:2020-02-19出版日期:2020-10-25发布日期:2020-08-24通讯作者:陈红基金资助:* 国家自然科学基金项目(31771237);中央高校基本科研业务费专项资金创新团队项目(SWU1709106);中央高校基本科研业务费专项资金创新团队项目(SWU1809355)Early life environmental unpredictability and overeating: Based on life history theory

LUO Yijun1,2, NIU Gengfeng3, CHEN Hong1,21School of Psychology, Southwest University, Chongqing 400715, China

2Key Laboratory of Cognition and Personality (Ministry of Education), Southwest University, Chongqing 400715, China

3School of Psychology, Central China Normal University, Wuhan 430079, China

Received:2020-02-19Online:2020-10-25Published:2020-08-24Contact:CHEN Hong 摘要/Abstract

摘要: 在生命史理论的视角下, 本研究通过两个研究揭示了生命早期环境不可预测性对过度进食的影响及其作用机制。研究1招募处于生命早期阶段的91名初中生(年龄12~14岁), 采用饱食进食(Eating in the absence of hunger, EAH)范式, 结果发现生命早期环境不可预测性能够显著正向预测个体饱食状态下的高热量食物选择(即过度进食); 研究2招募新冠病毒疾病(COVID-19)暴发背景下301名武汉市居民(高死亡威胁组)和179名其他省市居民(控制组) (年龄18~60岁)为被试, 通过问卷法回溯性地测量生命早期环境不可预测性并探究其影响当前过度进食的机制, 结果发现生命早期环境不可预测性通过生命史策略的中介作用间接影响过度进食。同时, 死亡威胁(新冠病毒疫情)扩大了环境不可预测性通过生命史策略间接影响过度进食的效应, 而社会支持则能缓冲这一效应。研究结果为COVID-19背景下和灾后居民的健康进食干预提供了依据。

图/表 8

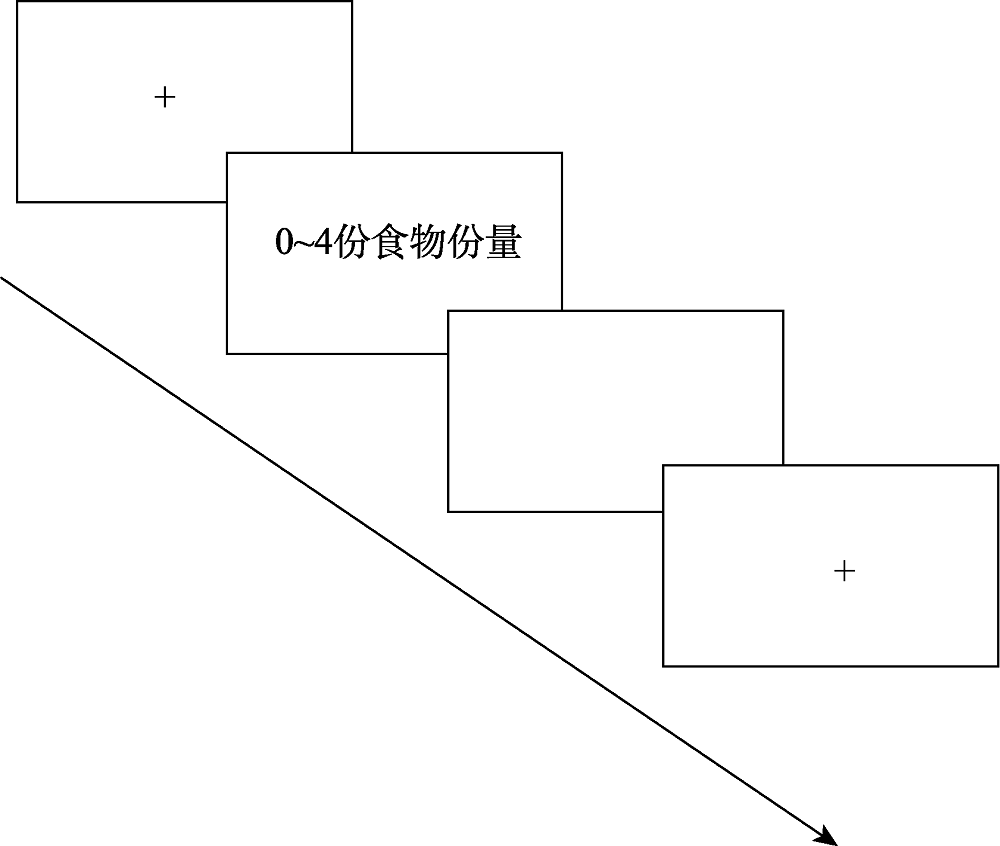

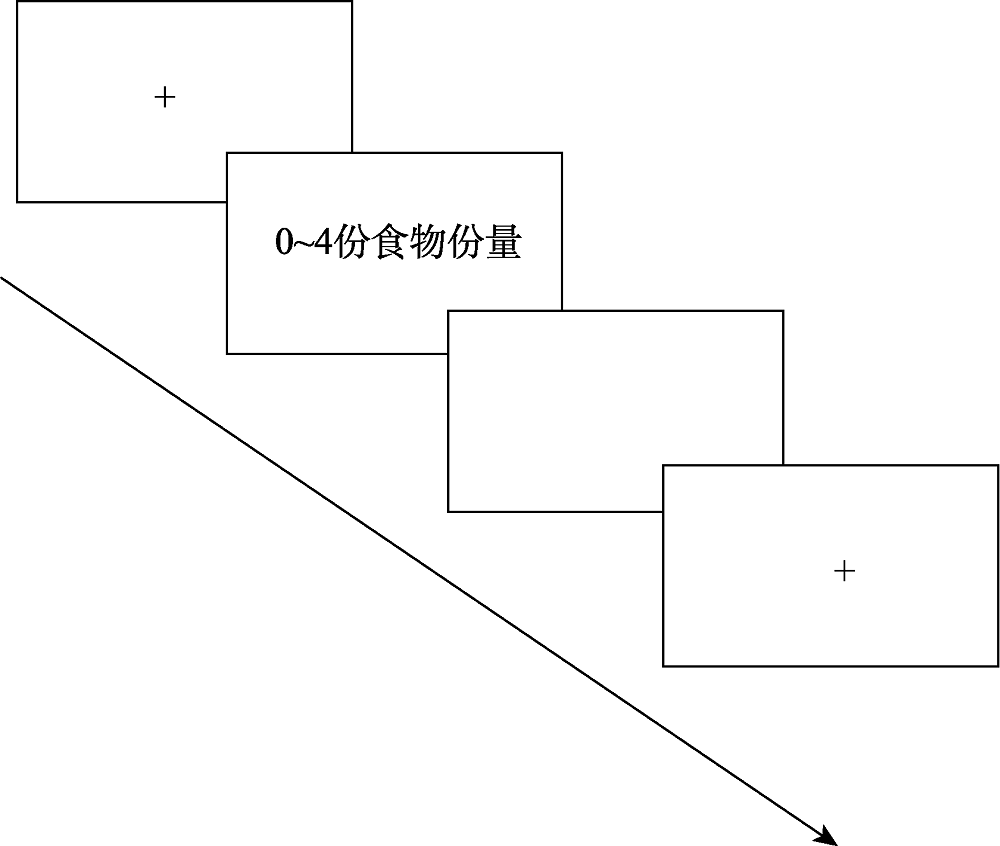

图1食物份量选择任务

图1食物份量选择任务

图1食物份量选择任务表1饥饿状态(饥饿vs. 饱食)对生命早期环境不可预测性与过度进食的调节作用

| 变量 | 低热量食物份量选择 | 高热量食物份量选择 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R2 | β(SE) | t | p | R2 | β(SE) | t | p | |

| 步骤一 | 0.08 | 0.12 | ||||||

| 年龄 | 0.08 (0.12) | 0.71 | 0.481 | 0.01 (0.11) | 0.09 | 0.930 | ||

| 性别(男生 = 0, 女生 = 1) | -0.12 (0.11) | -1.06 | 0.292 | -0.22 (0.11) | -1.98 | 0.051 | ||

| 身体质量指数(BMI) | -0.11 (0.03) | -1.01 | 0.314 | -0.07 (0.03) | -0.62 | 0.539 | ||

| 环境恶劣性 | 0.06 (0.03) | 0.55 | 0.586 | 0.06 (0.03) | 0.56 | 0.580 | ||

| 饥饿状态(饥饿 = 0, 饱食 = 1) | -0.12 (0.22) | -1.09 | 0.281 | -0.20 (0.21) | -1.82 | 0.072 | ||

| 环境不可预测性 | -0.14 (0.02) | -1.23 | 0.224 | 0.07 (0.02) | 0.65 | 0.518 | ||

| 步骤二 | 0.16* | 0.17* | ||||||

| 环境不可预测性×饥饿状态 | 0.89 (0.03) | 2.65** | 0.010 | 0.73 (0.03) | 2.20* | 0.030 | ||

表1饥饿状态(饥饿vs. 饱食)对生命早期环境不可预测性与过度进食的调节作用

| 变量 | 低热量食物份量选择 | 高热量食物份量选择 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R2 | β(SE) | t | p | R2 | β(SE) | t | p | |

| 步骤一 | 0.08 | 0.12 | ||||||

| 年龄 | 0.08 (0.12) | 0.71 | 0.481 | 0.01 (0.11) | 0.09 | 0.930 | ||

| 性别(男生 = 0, 女生 = 1) | -0.12 (0.11) | -1.06 | 0.292 | -0.22 (0.11) | -1.98 | 0.051 | ||

| 身体质量指数(BMI) | -0.11 (0.03) | -1.01 | 0.314 | -0.07 (0.03) | -0.62 | 0.539 | ||

| 环境恶劣性 | 0.06 (0.03) | 0.55 | 0.586 | 0.06 (0.03) | 0.56 | 0.580 | ||

| 饥饿状态(饥饿 = 0, 饱食 = 1) | -0.12 (0.22) | -1.09 | 0.281 | -0.20 (0.21) | -1.82 | 0.072 | ||

| 环境不可预测性 | -0.14 (0.02) | -1.23 | 0.224 | 0.07 (0.02) | 0.65 | 0.518 | ||

| 步骤二 | 0.16* | 0.17* | ||||||

| 环境不可预测性×饥饿状态 | 0.89 (0.03) | 2.65** | 0.010 | 0.73 (0.03) | 2.20* | 0.030 | ||

图2简单效应分析:(a)饥饿状态对环境不可预测性影响低热量食物份量选择的调节作用; (b)饥饿状态对环境不可预测性影响高热量食物份量选择的调节作用; EU指生命早期环境不可预测性; 低EU = 环境不可预测性得分为负一个标准差(-1 SD), 高EU = 环境不可预测性得分为正一个标准差(+1 SD)

图2简单效应分析:(a)饥饿状态对环境不可预测性影响低热量食物份量选择的调节作用; (b)饥饿状态对环境不可预测性影响高热量食物份量选择的调节作用; EU指生命早期环境不可预测性; 低EU = 环境不可预测性得分为负一个标准差(-1 SD), 高EU = 环境不可预测性得分为正一个标准差(+1 SD)

图2简单效应分析:(a)饥饿状态对环境不可预测性影响低热量食物份量选择的调节作用; (b)饥饿状态对环境不可预测性影响高热量食物份量选择的调节作用; EU指生命早期环境不可预测性; 低EU = 环境不可预测性得分为负一个标准差(-1 SD), 高EU = 环境不可预测性得分为正一个标准差(+1 SD)表2描述性统计与相关分析(n = 480)

| 变量 | M ± SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 年龄 | 27.44 ± 9.77 | — | ||||||

| 2 性别 | — | 0.07 | — | |||||

| 3 感知死亡威胁 | — | -0.03 | -0.02 | — | ||||

| 4 环境恶劣性 | 2.44 ± 0.96 | -0.09 | -0.07 | 0.05 | — | |||

| 5 环境不可预测性 | 2.94 ± 0.95 | -0.01 | 0.01 | 0.09* | 0.27*** | — | ||

| 6 快生命史策略 | 2.51 ± 0.94 | -0.04 | -0.10* | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.28*** | — | |

| 7 社会支持 | 4.97 ± 1.37 | 0.03 | 0.06 | -0.13** | -0.03 | -0.15** | -0.15** | — |

| 8 过度进食 | 2.18 ± 0.65 | -0.11* | -0.01 | 0.20*** | 0.21*** | 0.32*** | 0.32*** | -0.19*** |

表2描述性统计与相关分析(n = 480)

| 变量 | M ± SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 年龄 | 27.44 ± 9.77 | — | ||||||

| 2 性别 | — | 0.07 | — | |||||

| 3 感知死亡威胁 | — | -0.03 | -0.02 | — | ||||

| 4 环境恶劣性 | 2.44 ± 0.96 | -0.09 | -0.07 | 0.05 | — | |||

| 5 环境不可预测性 | 2.94 ± 0.95 | -0.01 | 0.01 | 0.09* | 0.27*** | — | ||

| 6 快生命史策略 | 2.51 ± 0.94 | -0.04 | -0.10* | 0.04 | 0.07 | 0.28*** | — | |

| 7 社会支持 | 4.97 ± 1.37 | 0.03 | 0.06 | -0.13** | -0.03 | -0.15** | -0.15** | — |

| 8 过度进食 | 2.18 ± 0.65 | -0.11* | -0.01 | 0.20*** | 0.21*** | 0.32*** | 0.32*** | -0.19*** |

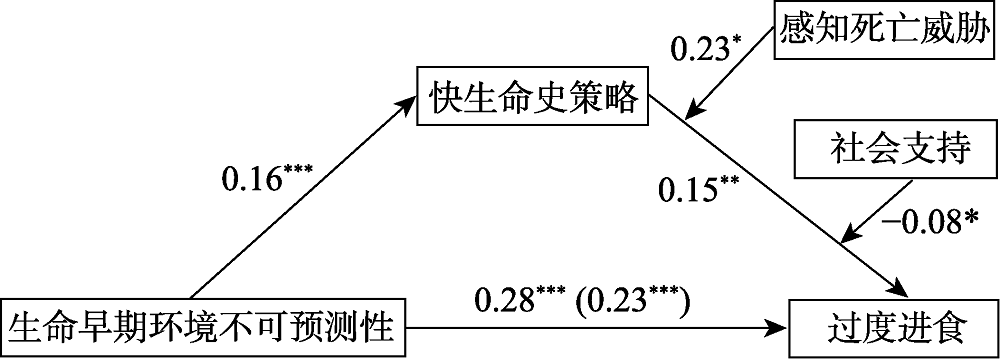

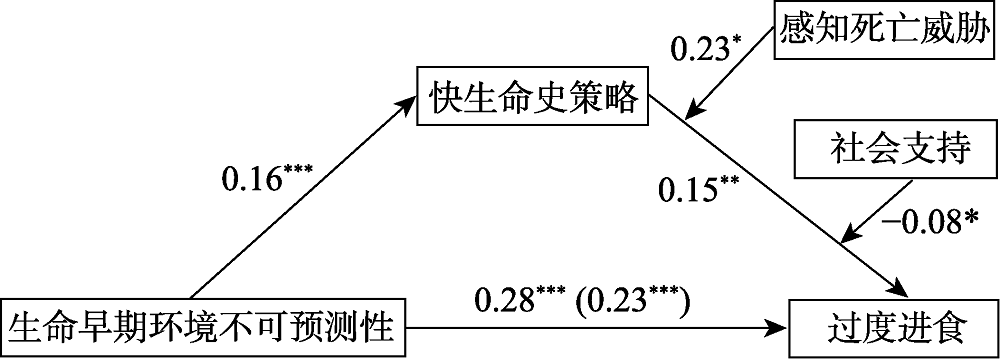

图3有调节的中介模型(注:所有路径系数为标准化的路径系数)

图3有调节的中介模型(注:所有路径系数为标准化的路径系数)

图3有调节的中介模型(注:所有路径系数为标准化的路径系数)表3有调节的中介模型的回归分析

| 变量 | R2 | β (SE) | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 因变量:过度进食 | 0.21*** | |||

| 性别 | 0.01 (0.05) | 0.14 | 0.889 | |

| 年龄 | -0.10 (0.01) | -2.49* | 0.013 | |

| 环境恶劣性 | 0.06 (0.03) | 2.03 | 0.043 | |

| 环境不可预测性 | 0.28 (0.03) | 9.72*** | < 0.001 | |

| 因变量:快生命史策略 | 0.09*** | |||

| 性别 | -0.11 (0.05) | -2.25* | 0.025 | |

| 年龄 | -0.01 (0.01) | -0.59 | 0.553 | |

| 环境恶劣性 | -0.01 (0.03) | -0.33 | 0.744 | |

| 环境不可预测性 | 0.16 (0.04) | 4.50*** | < 0.001 | |

| 因变量:过度进食 | 0.31*** | |||

| 性别 | 0.06 (0.05) | 1.25 | 0.214 | |

| 年龄 | -0.10 (0.04) | -2.62*** | 0.009 | |

| 环境恶劣性 | 0.04 (0.03) | 1.40 | 0.161 | |

| 环境不可预测性 | 0.23 (0.03) | 7.87*** | < 0.001 | |

| 快生命史策略 | 0.18 (0.06) | 3.04** | 0.003 | |

| 死亡威胁 | 0.16 (0.05) | 3.14** | 0.002 | |

| 社会支持 | -0.06 (0.02) | -2.37** | 0.018 | |

| 快生命史策略 × 社会支持 | -0.08 (0.03) | -2.52** | 0.012 | |

| 快生命史策略 × 死亡威胁 | 0.23 (0.11) | 2.14** | 0.033 |

表3有调节的中介模型的回归分析

| 变量 | R2 | β (SE) | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 因变量:过度进食 | 0.21*** | |||

| 性别 | 0.01 (0.05) | 0.14 | 0.889 | |

| 年龄 | -0.10 (0.01) | -2.49* | 0.013 | |

| 环境恶劣性 | 0.06 (0.03) | 2.03 | 0.043 | |

| 环境不可预测性 | 0.28 (0.03) | 9.72*** | < 0.001 | |

| 因变量:快生命史策略 | 0.09*** | |||

| 性别 | -0.11 (0.05) | -2.25* | 0.025 | |

| 年龄 | -0.01 (0.01) | -0.59 | 0.553 | |

| 环境恶劣性 | -0.01 (0.03) | -0.33 | 0.744 | |

| 环境不可预测性 | 0.16 (0.04) | 4.50*** | < 0.001 | |

| 因变量:过度进食 | 0.31*** | |||

| 性别 | 0.06 (0.05) | 1.25 | 0.214 | |

| 年龄 | -0.10 (0.04) | -2.62*** | 0.009 | |

| 环境恶劣性 | 0.04 (0.03) | 1.40 | 0.161 | |

| 环境不可预测性 | 0.23 (0.03) | 7.87*** | < 0.001 | |

| 快生命史策略 | 0.18 (0.06) | 3.04** | 0.003 | |

| 死亡威胁 | 0.16 (0.05) | 3.14** | 0.002 | |

| 社会支持 | -0.06 (0.02) | -2.37** | 0.018 | |

| 快生命史策略 × 社会支持 | -0.08 (0.03) | -2.52** | 0.012 | |

| 快生命史策略 × 死亡威胁 | 0.23 (0.11) | 2.14** | 0.033 |

表4不同条件下中介模型的间接效应量

| 分组 | 间接效应量(β) | 标准误(SE) | 上限(BootLLCI) | 下限(BootULCI) | 中介模型是否成立? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 高死亡威胁组 | |||||

| 高社会支持(> 1 SD) | 0.038 | 0.023 | 0.000 | 0.092 | 不成立 |

| 中等社会支持(1 SD) | 0.064 | 0.025 | 0.025 | 0.124 | 成立 |

| 低社会支持(< -1 SD) | 0.090 | 0.029 | 0.043 | 0.170 | 成立 |

| 控制组 | |||||

| 高社会支持(> 1 SD) | -0.017 | 0.021 | -0.060 | 0.027 | 不成立 |

| 中等社会支持(1 SD) | 0.010 | 0.017 | -0.020 | 0.051 | 不成立 |

| 低社会支持(< -1 SD) | 0.036 | 0.018 | 0.003 | 0.075 | 成立 |

表4不同条件下中介模型的间接效应量

| 分组 | 间接效应量(β) | 标准误(SE) | 上限(BootLLCI) | 下限(BootULCI) | 中介模型是否成立? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 高死亡威胁组 | |||||

| 高社会支持(> 1 SD) | 0.038 | 0.023 | 0.000 | 0.092 | 不成立 |

| 中等社会支持(1 SD) | 0.064 | 0.025 | 0.025 | 0.124 | 成立 |

| 低社会支持(< -1 SD) | 0.090 | 0.029 | 0.043 | 0.170 | 成立 |

| 控制组 | |||||

| 高社会支持(> 1 SD) | -0.017 | 0.021 | -0.060 | 0.027 | 不成立 |

| 中等社会支持(1 SD) | 0.010 | 0.017 | -0.020 | 0.051 | 不成立 |

| 低社会支持(< -1 SD) | 0.036 | 0.018 | 0.003 | 0.075 | 成立 |

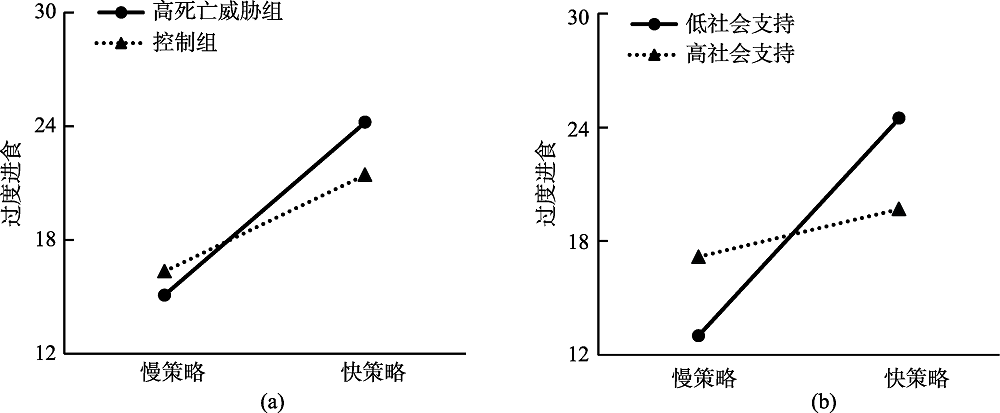

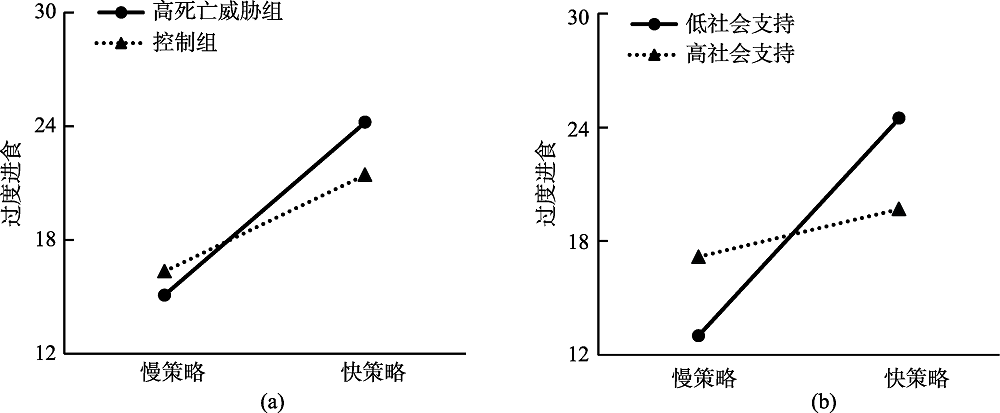

图4(a)死亡威胁对快生命史策略影响过度进食的调节作用; (b)社会支持对快生命史策略影响过度进食的调节作用; 慢策略 = 生命史策略得分为负一个标准差(-1 SD), 快策略 = 生命史策略得分为正一个标准差(+1 SD)

图4(a)死亡威胁对快生命史策略影响过度进食的调节作用; (b)社会支持对快生命史策略影响过度进食的调节作用; 慢策略 = 生命史策略得分为负一个标准差(-1 SD), 快策略 = 生命史策略得分为正一个标准差(+1 SD)

图4(a)死亡威胁对快生命史策略影响过度进食的调节作用; (b)社会支持对快生命史策略影响过度进食的调节作用; 慢策略 = 生命史策略得分为负一个标准差(-1 SD), 快策略 = 生命史策略得分为正一个标准差(+1 SD)参考文献 49

| [1] | Ahlstrom, B., Dinh, T., Haselton, M. G., & Janet Tomiyama, A. (2017). Understanding eating interventions through an evolutionary lens. Health Psychology Review, 11(1), 1-17. doi: 10.1080/17437199.2016.1190659URLpmid: 27189713 |

| [2] | Allg?wer, A., Wardle, J., & Steptoe, A. (2001). Depressive symptoms, social support, and personal health behaviors in young men and women. Health Psychology, 20(3), 223-227. URLpmid: 11403220 |

| [3] | Anglé, S., Engblom, J., Eriksson, T., Kautiainen, S., Saha, M. T., Lindfors, P., ... Rimpel?, A. (2009). Three factor eating questionnaire-R18 as a measure of cognitive restraint, uncontrolled eating and emotional eating in a sample of young Finnish females. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 6(1), 41-47. |

| [4] | Berkman, L. F., & Syme, S. L. (1979). Social networks, host resistance, and mortality: A nine-year follow-up study of Alameda County residents. American Journal of Epidemiology, 109(2), 186-204. URLpmid: 425958 |

| [5] | Chang, L., Lu, H. J., Lansford, J. E., Bornstein, M. H., Steinberg, L., Chen, B. B., ... Yotanyamaneewong, S. (2019a). External environment and internal state in relation to life history behavioural profiles of adolescents in nine countries. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 286, 20192097. URLpmid: 31847762 |

| [6] | Chang, L., Lu, H. J., Lansford, J. E., Skinner, A. T., Bornstein, M. H., Steinberg, L., ... Tapanya, S. (2019b). Environmental harshness and unpredictability, life history, and social and academic behavior of adolescents in nine countries. Developmental Psychology, 55(4), 890-903. URLpmid: 30507220 |

| [7] | Chen, X. M., Luo, Y. J., & Chen, H. (2020a). Body image victimization experiences and disordered eating behaviors among Chinese female adolescents: The role of body dissatisfaction and depression. Sex Roles. doi: 10.1007/s11199-017-0799-yURLpmid: 29491550 |

| [8] | Chen, X. M., Luo, Y. J., & Chen, H. (2020b). Friendship quality and adolescents’ intuitive eating: A serial mediation model and the gender difference. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 52(4), 485-496. doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1041.2020.00485URL |

| [ 陈曦梅, 罗一君, 陈红. (2020b). 友谊质量与青少年直觉进食:链式中介模型及性别差异. 心理学报, 52(4), 485-496.] | |

| [9] | Cheon, B. K., & Hong, Y. Y. (2017). Mere experience of low subjective socioeconomic status stimulates appetite and food intake. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114(1), 72-77. |

| [10] | Danese, A., & Tan, M. (2014). Childhood maltreatment and obesity: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Molecular Psychiatry, 19(5), 544-554. URLpmid: 23689533 |

| [11] | Dukes H. K., & Holahan, C. K. (2003). The relation of social support and coping to positive adaptation to breast cancer. Psychology and Health, 18(1), 15-29. |

| [12] | Ellis, B. J., Figueredo, A. J., Brumbach, B. H., & Schlomer, G. L. (2009). Fundamental dimensions of environmental risk. Human Nature, 20(2), 204-268. URLpmid: 25526958 |

| [13] | Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A.-G. & Buchner, A. (2007). G*Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39, 175-191. doi: 10.3758/bf03193146URLpmid: 17695343 |

| [14] | Figueredo, A. J., Vásquez, G., Brumbach, B. H., Schneider, S. M. R., Sefcek, J. A., Tal, I. R., ... Jacobs, W. J. (2006). Consilience and life history theory: From genes to brain to reproductive strategy. Developmental Review, 26, 243-275. doi: 10.1016/j.dr.2006.02.002URL |

| [15] | Griskevicius, V., Delton, A. W., Robertson, T. E., & Tybur, J. M. (2011). Environmental contingency in life history strategies: The influence of mortality and socioeconomic status on reproductive timing. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 100(2), 241-254. doi: 10.1037/a0021082URL |

| [16] | Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. New York, USA: Guilford Press. |

| [17] | Hemmingsson, E. (2018). Early childhood obesity risk factors: Socioeconomic adversity, family dysfunction, offspring distress, and junk food self-medication. Current obesity Reports, 7(2), 204-209. doi: 10.1007/s13679-018-0310-2URLpmid: 29704182 |

| [18] | Hemmingsson, E., Johansson, K., & Reynisdottir, S. (2014). Effects of childhood abuse on adult obesity: A systematic review and meta analysis. Obesity Reviews, 15(11), 882-893. URLpmid: 25123205 |

| [19] | Hill, S. E., Prokosch, M. L., DelPriore, D. J., Griskevicius, V., & Kramer, A. (2016). Low childhood socioeconomic status promotes eating in the absence of energy need. Psychological Science, 27(3), 354-364. doi: 10.1177/0956797615621901URLpmid: 26842316 |

| [20] | Lipson, S. K., & Sonneville, K. R. (2017). Eating disorder symptoms among undergraduate and graduate students at 12 US colleges and universities. Eating Behaviors, 24, 81-88. URLpmid: 28040637 |

| [21] | Lu, H. J., & Chang, L. (2019). Aggression and risk‐taking as adaptive implementations of fast life history strategy. Developmental Science, 22, e12827. doi: 10.1111/desc.12827URLpmid: 30887602 |

| [22] | Malecki, C. K., & Demaray, M. K. (2003). What type of support do they need? investigating student adjustment as related to emotional, informational, appraisal, and instrumental support. School Psychology Quarterly, 18(3), 231-252. |

| [23] | Maner, J. K., Dittmann, A., Meltzer, A. L., & McNulty, J. K. (2017). Implications of life-history strategies for obesity. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 114(32), 8517-8522. |

| [24] | Marroquín, B., & Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2015). Emotion regulation and depressive symptoms: Close relationships as social context and influence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 109(5), 836-855. URLpmid: 26479366 |

| [25] | McEwen, M. M., Pasvogel, A., Gallegos, G., & Barrera, L. (2010). Type 2 diabetes self‐management social support intervention at the US‐Mexico border. Public Health Nursing, 27(4), 310-319. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2010.00860.xURLpmid: 20626831 |

| [26] | Miller, A. L., Gearhardt, A. N., Retzloff, L., Sturza, J., Kaciroti, N., & Lumeng, J. C. (2018). Early childhood stress and child age predict longitudinal increases in obesogenic eating among low-income children. Academic Pediatrics, 18(6), 685-691. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2018.01.007URLpmid: 29357310 |

| [27] | Mittal, C., & Griskevicius, V. (2014). Sense of control under uncertainty depends on people’s childhood environment: A life history theory approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 107(4), 621-637. doi: 10.1037/a0037398URLpmid: 25133717 |

| [28] | Mittal, C., Griskevicius, V., Simpson, J. A., Sung, S., & Young, E. S. (2015). Cognitive adaptations to stressful environments: When childhood adversity enhances adult executive function. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 109(4), 604-621. doi: 10.1037/pspi0000028URLpmid: 26414842 |

| [29] | Nieto, M. M., Wilson, J., Cupo, A., Roques, B. P., & Noble, F. (2002). Chronic morphine treatment modulates the extracellular levels of endogenous enkephalins in rat brain structures involved in opiate dependence: A microdialysis study. Journal of Neuroscience, 22, 1034-1041. URLpmid: 11826132 |

| [30] | Prentice, A. M. (2001). Overeating: the health risks. Obesity Research, 9(S11), 234S-238S. |

| [31] | Proffitt Leyva, R. P., & Hill, S. E. (2018). Unpredictability, body awareness, and eating in the absence of hunger: A cognitive schemas approach. Health Psychology, 37(7), 691-699. doi: 10.1037/hea0000634URLpmid: 29902053 |

| [32] | Ross, L. T., & Hill, E. M. (2000). The family unpredictability scale: Reliability and validity. Journal of Marriage and Family, 62(2), 549-562. |

| [33] | Salmon, C., Figueredo, A. J., & Woodburn, L. (2009). Life history strategy and disordered eating behavior. Evolutionary Psychology, 7(4), 585-600. |

| [34] | Shapiro, A. L. B., Johnson, S. L., Sutton, B., Legget, K. T., Dabelea, D., & Tregellas, J. R. (2019). Eating in the absence of hunger in young children is related to brain reward network hyperactivity and reduced functional connectivity in executive control networks. Pediatric Obesity, 14, e12502. doi: 10.1111/ijpo.12502URLpmid: 30659756 |

| [35] | Sim, A. Y., Lim, E. X., Forde, C. G., & Cheon, B. K. (2018). Personal relative deprivation increases self-selected portion sizes and food intake. Appetite, 121, 268-274. |

| [36] | Stewart, M., Barnfather, A., Magill-Evans, J., Ray, L., & Letourneau, N. (2011). Brief report: An online support intervention: Perceptions of adolescents with physical disabilities. Journal of Adolescence, 34(4), 795-800. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2010.04.007URLpmid: 20488511 |

| [37] | Stewart, M., Simich, L., Shizha, E., Makumbe, K., & Makwarimba, E. (2012). Supporting African refugees in Canada: Insights from a support intervention. Health & Social Care in the Community, 20(5), 516-527. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2012.01069.xURLpmid: 22639987 |

| [38] | Striegel-Moore, R. H., & Bulik, C. M. (2007). Risk factors for eating disorders. American Psychologist, 62(3), 181-198. URLpmid: 17469897 |

| [39] | Tong, J., Miao, S., Wang, J., Yang, F., Lai, H., Zhang, C., ... Hsu, L. G. (2014). A two-stage epidemiologic study on prevalence of eating disorders in female university students in Wuhan, China. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 49(3), 499-505. doi: 10.1007/s00127-013-0694-yURLpmid: 23744441 |

| [40] | Volkow, N., Wang, G. J., Fowler, J. S., Tomasi, D., & Baler, R. (2011). Food and drug reward: Overlapping circuits in human obesity and addiction. In J. W. Dalley & C. S. Carter (Eds.), Brain Imaging in Behavioral Neuroscience (pp. 1-24). Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg. doi: 10.1037/bne0000131URLpmid: 26881313 |

| [41] | Wang, J. Y., & Chen, B. B. (2016). The influence of childhood stress and mortality threat on mating standards. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 48(7), 857-866. |

| [ 汪佳瑛, 陈斌斌. (2016). 童年压力及死亡威胁启动对择偶要求的影响. 心理学报, 48(7), 857-866.] | |

| [42] | Wang, X. D., Wang, X. L., & Ma, H. (1999). Handbook of mental health assessment scale. Chinese Mental Health Journal, 13(1), 31-35. |

| [ 汪向东, 王希林, 马弘. (1999). 心理卫生评定量表手册. 中国心理卫生杂志, 13(1), 31-35.] | |

| [43] | Wang, Y., Lin, Z. C., Hou, B. W., & Sun, S. J. (2017). The intrinsic mechanism of life history trade-offs: The mediating role of control striving. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 49(6), 783-793. |

| [ 王燕, 林镇超, 侯博文, 孙时进. (2017). 生命史权衡的内在机制: 动机控制策略的中介作用. 心理学报, 49(6), 783-793.] | |

| [44] | White, M., & Dorman, S. M. (2001). Receiving social support online: Implications for health education. Health Education Research, 16(6), 693-707. doi: 10.1093/her/16.6.693URLpmid: 11780708 |

| [45] | Wonderlich-Tierney, A. L., & vander Wal, J. S. (2010). The effects of social support and coping on the relationship between social anxiety and eating disorders. Eating Behaviors, 11(2), 85-91. doi: 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2009.10.002URLpmid: 20188291 |

| [46] | Yao, R. S., Guo, M. S., & Ye, H. S. (2018). The mediating effects of hope and loneliness on the relationship between social support and social well-being in the elderly. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 50(10), 1151-1158. |

| [ 姚若松, 郭梦诗, 叶浩生. (2018). 社会支持对老年人社会幸福感的影响机制: 希望与孤独感的中介作用. 心理学报, 50(10), 1151-1158.] | |

| [47] | Zhou, H., & Long, L. R. (2004). Statistical remedies for common method biases. Advances in Psychological Science, 12(6), 942-950. |

| [ 周浩, 龙立荣. (2004). 共同方法偏差的统计检验与控制方法. 心理科学进展, 12(6), 942-950.] | |

| [48] | Zhou, X., Wu, X. C., Zeng, M., & Tian, Y. X. (2016). The relationship between emotion regulation and PTSD/PTG among adolescents after the Ya’an earthquake: The moderating role of social support. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 48(8), 969-980. |

| [ 周宵, 伍新春, 曾旻, 田雨馨. (2016). 青少年的情绪调节策略对创伤后应激障碍和创伤后成长的影响: 社会支持的调节作用. 心理学报, 48(8), 969-980.] | |

| [49] | Ziauddeen, H., & Fletcher, P. C. (2013). Is food addiction a valid and useful concept?. Obesity Reviews, 14(1), 19-28. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2012.01046.xURLpmid: 23057499 |

相关文章 4

| [1] | 王燕,侯博文,刘文锦. 童年亲子关系与“好资源”对未婚男性性开放态度的影响[J]. 心理学报, 2020, 52(2): 207-215. |

| [2] | 王燕, 侯博文, 李歆瑶, 李晓煦, 焦璐. 不同性别比和资源获取能力 对未婚男性择偶标准的影响[J]. 心理学报, 2017, 49(9): 1195-1205. |

| [3] | 王 燕, 林镇超, 侯博文, 孙时进. 生命史权衡的内在机制:动机控制策略的中介作用[J]. 心理学报, 2017, 49(6): 783-793. |

| [4] | 汪佳瑛; 陈斌斌. 童年压力及死亡威胁启动对择偶要求的影响[J]. 心理学报, 2016, 48(7): 857-866. |

PDF全文下载地址:

http://journal.psych.ac.cn/xlxb/CN/article/downloadArticleFile.do?attachType=PDF&id=4810