,1,2,*

,1,2,*Difference in fungal communities between in roots and in root-associated soil of nine orchids in Liaoning, China

Yu-Ling JIANG1, Xu-Hui CHEN1, Qing MIAO1, Bo QU ,1,2,*

,1,2,*通讯作者: *syauqb@163.com

编委: 陈保冬

责任编辑: 赵航(实习)

收稿日期:2019-03-12接受日期:2019-11-18网络出版日期:2019-12-20

| 基金资助: |

Corresponding authors: *syauqb@163.com

Received:2019-03-12Accepted:2019-11-18Online:2019-12-20

| Fund supported: |

摘要

兰科植物的生存及生长高度依赖其根中的共生真菌, 其中的菌根真菌更是对兰科植物的种子萌发与后续生长有着非常重要的作用, 研究兰科植物根中的真菌, 尤其是菌根真菌, 对兰科植物的保护有重要作用。该研究利用第二代测序技术, 对中国辽宁省境内的9种属于极小种群的兰科植物的根、根际土和根围土中的真菌群落和菌根真菌组成进行了研究。结果显示, 兰科植物根中的真菌群落和根际土、根围土中的真菌群落具有显著差异。兰科植物根中的总操作分类单元(OTU)数目远小于根际土和根围土中的总OTU数目。同时, 兰科植物根中菌根真菌的种类和丰度与根际土、根围土中菌根真菌的种类与丰度没有明显联系。FunGuild分析结果显示, 丛枝菌根真菌在根际土与根围土中的丰度非常高, 但在兰科植物的根中却数量极少。这些结果表明, 兰科植物根中的真菌群落与土壤中的真菌群落在一定程度上是相互独立的。

关键词:

Abstract

Aims Orchid plants generally grow better when they are mycorrhizal since mycorrhizal fungi are likely to assist in orchid seeds’ germination. However, there is little quantitative work on it. Thus we hope to better understand this mechanism to benefit the orchid plants protection.

Methods We studied nine small population species of orchids grown in Liaoning Province, China. We analyzed the composition of orchid mycorrhizal fungi (OMF) and fungal communities in the roots, in the rhizosphere soil as well as bulk soil, by taking advantage of the next generation sequencing technology.

Important findings Our study showed that there was a significant difference in fungal communities among in the roots, the rhizosphere soil and the bulk soil, especially in the total operational taxonomic unit (OTU) number. Although the OTU number was far smaller in the roots than in the rhizosphere soil and bulk soil, the species and abundances of OMF were less relative to each other. FunGuild, an indicator to predict the functional fungi, indicated that Arbuscular Mycorrhizal fungi were abundence in the rhizosphere while were rare in the roots of orchids. In general, the fungal communities in the roots were not tightly correlated with that in the root-associated soil.

Keywords:

PDF (1277KB)元数据多维度评价相关文章导出EndNote|Ris|Bibtex收藏本文

引用本文

蒋玉玲, 陈旭辉, 苗青, 曲波. 辽宁省9种兰科植物根内与根际土壤中真菌群落结构的差异. 植物生态学报, 2019, 43(12): 1079-1090. DOI: 10.17521/cjpe.2019.0055

JIANG Yu-Ling, CHEN Xu-Hui, MIAO Qing, QU Bo.

兰科植物大多数具有极高的药用与观赏价值, 全世界共有28 000种以上, 且所有野生兰科植物均被列入《野生动植物濒危物种国际贸易公约》, 并占该公约所保护植物的90%以上, 毫无疑问, 其是受保护野生植物中的“旗舰”类群。兰科植物的生存与其根中的共生真菌, 尤其是一些特异性菌根真菌高度相关(Smith & Read, 2008), 研究兰科植物与共生真菌的关系有助于兰科植物的保护与种群重建。

兰科植物根中存在着非常丰富的真菌群落, 我们可以将其分为菌根真菌与非菌根真菌两大类。众所周知, 兰科植物的萌发及后续生长均强烈依赖于其根中的特异性菌根真菌。但也正因如此, 在以往与兰科植物保护有关的研究中, 对于兰科植物根中的菌群, 人们往往只关注菌根真菌, 而忽视了兰科植物根中的非菌根真菌。实际上, 兰科植物根中的非菌根真菌数量也非常庞大, 甚至远多于菌根真菌的数量(Jacquemyn et al., 2016; Novotná et al., 2018)。这些非菌根真菌与菌根真菌之间有着非常重要的相互关系。目前的研究认为, 植物通常可以和许多内生真菌共生, 并在某些条件下从这种共生关系中获利(Shakya et al., 2013)。比如Fusarium便是一种兰科植物根中常见的非菌根真菌, 它在一定情况下会诱导植物疾病的产生, 但也能有效促进兰科植物种子的萌发(Vujanovic et al., 2000)。Helotiales真菌能与非兰科植物Pyrola rotundifolia共生(Vincenot et al., 2008)。而Pyrola rotundifolia是一种能和兰科Epipactis属植物共生的植物, 即兰科植物可能会和非兰科植物与同种Helotiales真菌共生(Jacquemyn et al., 2016), 并通过这种真菌进行能量交换。广泛存在于各种兰科植物根中的Trichoderma, 可以分泌出对氰化物有降解作用的酶, 以控制植物根中的某些病原菌, 促进植物生长, 维持植物健康(Ezzi & Lynch, 2002)。Ma等(2015)也认为, 兰科植物根中的非菌根真菌可能会帮助植物抵御土壤中病原菌的侵害。因此, 研究兰科植物根中的非菌根真菌, 与菌根真菌一样, 也对兰科植物的保护有着重要意义。

与此同时, 在兰科植物的生长过程中, 土壤中的菌根真菌可以通过多种方式进入兰科植物的根中, 与兰科植物形成共生关系, 比如, 有的菌根真菌通过破坏兰科植物的根被组织或通道细胞侵入兰科植物根的皮层内。据此, 土壤中合适的菌根真菌丰度越大, 则能与生长在该地点的兰科植物形成共生关系的菌根真菌越多, 就越有利于兰科植物的生长。比如, McCormick等(2016)设计了3种陆生兰科植物的种子萌发实验, 并提取其周围土壤DNA进行测序以分析土壤中的真菌分布情况, 结果发现, 有种子萌发的地方, 该植物的特异共生真菌丰度一般较高, 且越靠近成熟兰科植物, 真菌丰度越高。Bougoure等(2009)也提出, 通过对土壤中菌根真菌的检测, 可判断该地点是否适合相应兰科植物的生长。因此, 研究兰科植物根中菌根真菌在周围土壤中的动态分布, 对兰科植物的保护和种群修复具有重要作用。然而, 从目前的研究来看, 我们对兰科植物菌根真菌在土壤中的动态分布仍知之甚少。一些研究通过比较菌根和土壤中的真菌群落结构, 对兰科植物根内的菌根真菌和周围土壤中的菌根真菌进行了研究, 结果显示, 大部分在根中发现的菌根真菌在土壤中也广泛分布, 且随着取样地点离宿主植物距离的增加, 相应的菌根真菌多样性和丰度逐渐减少(McCormick et al., 2012; Waud et al., 2016)。然而, 另一些相关研究的结果却显示, 兰科植物根内的菌根真菌群落结构和土壤中的菌根真菌群落结构显著不同, 菌根真菌在根内的丰度是最大的, 只有少数菌根真菌在土壤样本中出现(Liu et al., 2015; Oja et al., 2015; Han et al., 2016)。比如, Voyron等(2017)在对Anacamptis morio和Ophrys sphegodes根内及其周围土壤中的菌根真菌进行研究时, 发现这两种兰科植物周围土壤中的菌根真菌丰度并未随着植物距离的增加而减少, 且菌根真菌的变化与取样地点离成熟兰科植物的距离之间并没有明显的相关性。这些结果使得兰科植物菌根真菌在土壤中的动态分布显得更加神秘, 也带给了我们许多疑问, 比如, 兰科植物菌根真菌在土壤中的分布是否真的和宿主兰科植物的位置有关, 且会随着与兰科植物距离的增加而减少(McCormick et al., 2012; Waud et al., 2016), 还是如Han等(2016)的研究结果一样, 菌根真菌在土壤中的分布与兰科植物无明显关系, 兰科植物根内的真菌群落与根际土和根围土中的真菌群落是否有巨大差异。

中国东北地区位于39.20°-53.92° N, 115.87°- 135.15° E, 处于北半球的中高纬度, 也是中国纬度最高, 气候变化最明显、最敏感的地区(孙凤华等, 2006), 从北向南有寒温带、温带和暖温带的热量变化, 具有独特的植被分布格局(王绍强等, 2001), 具有重要的研究价值。而辽宁省属温带大陆性季风气候, 植被类型丰富多样(王治红等, 2005), 以辽宁省桓仁满族自治县为中心的辽东地区和辽宁省庄河市所辖的辽南地区, 更是中国东北地区受威胁植物的优先保护区域, 拥有在东北的全部受威胁兰科植物物种, 是十分重要的兰科植物集中保护地(曹伟等, 2013)。目前辽宁共有兰科植物22属34种, 其中大部分为单种属。同时, 存在于中国东北地区的兰科植物种群多数以极小种群的形式存在, 如在世界上只有3个种群, 极其珍稀濒危的野生物种——双蕊兰(Diplandrorchis sinica); 还有的兰科植物甚至以单株的形式存在, 如长苞头蕊兰(Cephalanthera longibracteata)、小斑叶兰(Goodyera repens)、蜻蜓兰(Tulotis fuscescens)和二叶舌唇兰(Platanthera chlorantha)等, 生存状况极不乐观。

近年来, 第二代测序技术被广泛应用于微生物群落的研究中, Egidi等(2018)的研究也证实, 第二代测序技术可用于兰科植物菌根真菌在土壤中分布的相关研究。因此, 本研究利用第二代高通量测序技术对中国辽宁省境内的珊瑚兰(Corallorhiza trifida)、二叶舌唇兰、无柱兰(Amitostigma gracile)、小斑叶兰、长苞头蕊兰、山兰(Oreorchis patens)、羊耳蒜(Liparis campylostalix)、蜻蜓兰和绶草(Spiranthes sinensis)这9种兰科植物的根、根际土和根围土中的真菌群落进行了研究, 以期全面了解兰科植物根内与根际土壤中真菌群落结构的差异, 探究兰科植物根、根际土与根围土中真菌群落之间的关系, 为深入研究兰科植物菌根真菌和环境的关系, 极小种群的保育以及中国东北地区兰科植物的物种保护与野生种群生态恢复提供理论依据。

1 材料和方法

1.1 样本采集与预处理

本研究共涉及9种兰科植物, 分别是细葶无柱兰、长苞头蕊兰、绶草、珊瑚兰、蜻蜓兰、羊耳蒜、小斑叶兰、二叶舌唇兰和山兰。这9种兰科植物采于中国东北地区的辽宁省境内, 具体采集地点如表1所示。每种植物取叶片、根、根际土和根围土4份样本, 一共60份样本。Table 1

表1

表1辽宁省9种兰科植物物种鉴定与采集

Table 1

| 植物种类 Species | 株数 Number | 采集地点 Location | 生境 Biotope | 生育期 Growth stage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 无柱兰 Amitostigma gracile | 1 | 辽宁大连庄河市塔子沟 Tazigou, Zhuanghe, Dalian, Liaoning | 阔叶林下水边悬崖 Waterside cliff under a broad-leaved forest | 营养期 Vegetative period |

| 长苞头蕊兰 Cephalanthera longibracteata | 1 | 辽宁大连庄河市塔子沟 Tazigou, Zhuanghe, Dalian, Liaoning | 针阔混交林 Mixed broadleaf-conifer forest | 花期 Flowering phase |

| 小斑叶兰 Goodyera repens | 1 | 辽宁大连庄河市塔子沟 Tazigou, Zhuanghe, Dalian, Liaoning | 阔叶林下水边悬崖 Waterside cliff under a broad-leaved forest | 花期 Flowering phase |

| 二叶舌唇兰 Platanthera chlorantha | 4 | 辽宁凤城市、凌源市、本溪市与庄河市 Fengcheng, Lingyuan, Benxi and Zhuanghe, Liaoning | 针阔混交林 Mixed broadleaf-conifer forest | 营养期、花期 Vegetative period & Flowering phase |

| 蜻蜓兰 Tulotis fuscescens | 1 | 辽宁丹东凤城市 Fengcheng, Dandong, Liaoning | 针阔混交林 Mixed broadleaf-conifer forest | 花期 Flowering phase |

| 羊耳蒜 Liparis campylostalix | 1 | 辽宁大连庄河市姑庵庙 Gu’anmiao, Zhuanghe, Dalian, Liaoning | 针阔混交林 Mixed broadleaf-conifer forest | 营养期 Vegetative period |

| 珊瑚兰 Corallorhiza trifida | 1 | 辽宁凌源与河北承德市交界处 Junction of Lingyuan, Liaoning and Chengde, Hebei | 阔叶林 Broad-leaved forest | 营养期 Vegetative period |

| 绶草 Spiranthes sinensis | 3 | 辽宁阜新市杜家店水库 Dujiadian Reservoir, Fuxin, Liaoning | 湖泊边草甸 Meadow beside a lake | 花期 Flowering phase |

| 山兰 Oreorchis patens | 2 | 辽宁本溪市本溪县沟门和老秃顶子 Goumen and Laotudingzi in Benxi County, Benxi, Liaoning | 针阔混交林 Mixed broadleaf-conifer forest | 花期 Flowering phase |

新窗口打开|下载CSV

采样时, 先用灭菌后的小铲采集植物周围半径5 cm以内的土壤, 装入无菌自封袋中, 放入冰盒暂存, 作为根围土样本; 随后小心地将植物连根拔起, 抖掉根周围松散的土壤, 用灭菌后的剪刀剪取部分植物带土根系, 置于装有0.85% NaCl溶液的25 mL灭菌离心管中, 放入冰盒暂存, 带回实验室后放入冰中30 min, 每隔5 min取出摇匀1次, 然后将根系取出, 将离心管置于离心机中4 000 × g 4 ℃低温离心10 min, 除去上清液, 将得到的土壤沉淀物保存于无菌自封袋中, 于4 ℃冰箱内保存, 作为根际土样本(Gremion et al., 2003); 根系则剪成2-3 cm长的小段, 先用自来水冲洗干净, 再用蒸馏水清洗, 放入0.1%的升汞中浸泡5-10 min (时间长短据根的大小而定), 取出后用蒸馏水冲洗, 再放入75%酒精中浸泡20 s左右, 最后用蒸馏水冲洗干净, 晾干后放入无菌自封袋, 置于4 ℃冰箱中保存。叶片则用无菌刀片切成小片, 用蒸馏水冲洗干净, 放入无菌自封袋中加硅胶干燥, 置于4 ℃冰箱中, 最后将所有得到的样本转移至-80 ℃冰箱中保存用于后续DNA提取与测序。

1.2 实验方法

本实验的每种植物都采了叶片、根、根际土和根围土4份样本。其中, 叶片用于提取DNA并扩增ITS1序列, 以精确鉴定植物的种类, 物种鉴定结果如表1所示。而根、根际土与根围土样本则用于提取样本中的宏基因组DNA, 测定样本中真菌的ITS1序列, 以鉴定样本中真菌群落的组成(蒋玉玲, 2018)。1.2.1 根、根际土和根围土样本中真菌基因组DNA提取、扩增及测序

利用MoBio PowerSoil? DNA Isolation Kit (MoBio Laboratories, USA)试剂盒, 按照说明书中的步骤提取样本中的微生物组总DNA, 并通过0.8%琼脂糖凝胶电泳检测DNA提取质量, 同时采用Nanodrop紫外分光光度计(Thermo Fisher Scienti?c, Wilmington, Delaware, USA)对DNA进行定量。以提取得到的DNA为模板, 真菌核糖体DNA中的ITS序列为靶点, 真菌通用引物ITS5F (5′-GGAAGTAAAAGTCGTAACAAGG-3′)为前引物, ITS1R (5′-GCTGCGTTCTTCATCGATGC-3′)为后引物, 并为每个样本添加特异性Barcode序列, 对各样本中的真菌ITS1区域进行扩增。扩增体系采用25 μL体系, 即 5 μL 5 × reaction buffer, 5 μL 5 × GC buffer, 2 μL dNTP (2.5 mmol·L-1), 1 μL前引物Forwardprimer (10 μmol·L-1), 1 μL后引物(10 μmol·L-1), 2 μL DNA模板, 8.75 μL ddH2O, 0.25 μL Q5 DNA Polymerase。扩增程序为: 98 ℃ 2 min, 98 ℃ 15 s, 55 ℃ 30 s, 循环25-27次, 72 ℃ 30 s, 72 ℃ 5 min, 最后于10 ℃保温。将PCR扩增产物通过2%琼脂凝胶糖电泳进行检测与纯化, 并采用AXYGEN公司的凝胶回收试剂盒对目标片段进行切胶回收。参照电泳初步定量结果, 将PCR扩增回收产物进行荧光定量(荧光试剂为Quant-iT PicoGreen dsDNA Assay Kit, 定量仪器为Microplate reader (FLx800, BioTek, Vermont, USA))。根据荧光定量结果, 按照每个样本的测序量需求, 对各样本按相应比例进行混合。

采用Illumina公司的TruSeq Nano DNA LT Library Prep Kit制备测序文库, 再用Agilent High Sensitivity DNA Kit对构建的文库进行质检, 若文库有且只有单一的峰, 且无接头, 则合格。将合格的各上机测序文库梯度稀释后, 根据所需测序量按相应比例混合, 并经NaOH变性为单链进行上机测序; 使用MiSeq测序仪进行2 × 250 bp的双端测序, 相应试剂为MiSeq Reagent Kit V3 (600 cycles)。

在得到测序数据后, 首先运用QIIME软件(Quantitative Insights Into Microbial Ecology, v1.8.0,

1.2.2 数据库选择与测序数据筛选

本实验主要研究兰科植物根和根周围土壤中的真菌群落, 因此选用了专门针对真菌ITS序列的UNITE数据库, 以及常用的GenBank数据库, 在比较了这两个数据库的比对结果之后却发现, 同样的测序数据在两个数据库中的匹配完全程度与正确率出现了差异, 即在UNITE数据库中比对的数据匹配率要高于GenBank数据库, 但在UNITE数据库比对得到的数据出现了误配的现象, 使部分非真菌序列在UNITE数据库中被匹配为了真菌序列, 导致部分比对结果出错, 不利于对兰科植物根内真菌群落的真实研究。因此, 在比较了两个数据库的比对数据后, 本研究选择了正确率更高的GenBank数据库。为了保证后续分析结果的准确性, 我们在进行数据分析之前去除了真菌之外的OTU数据, 保留了没有得到鉴定结果的序列与真菌序列, 只对筛选后的OTU矩阵进行了数据分析。

1.2.3 数据分析

利用QIIME软件, 对OTU丰度矩阵中的每个样本的序列总数在不同深度下随机抽样, 以每个深度下抽取到的序列数及对应的OTU数绘制稀疏曲线, 衡量每个样本的多样性高低。再使用QIIME软件分别计算每个样本的α多样性指数, 包括Simpson多样性指数、Shannon多样性指数、Chao1丰富度估计指数(Chao, 1984)和ACE丰富度估计指数(Chao & Yang, 1993)。

利用Excel计算样本间的Jaccard Index, 以比较各样本中真菌群落的相似性, 并绘制各样本的真菌群落组成柱状图与饼状图, 以分析真菌的群落组成结构。

使用R软件, 对OTU丰度矩阵中每个样本所对应的OTU总数绘制Specaccum物种累积曲线, 以判断样本量是否足够大; 对丰度前50位的属进行聚类分析, 绘制热图; 对属水平上的群落组成结构进行主成分分析(PCA), 并计算各样本之间的Unweighted Unifrac距离(Lozupone & Knight, 2005)和Weighted Unifrac距离(Lozupone et al., 2007), 并基于Unweighted和Weighted的Unifrac距离矩阵分别进行NMDS分析、UPGMA聚类分析、adonis分析、anosim分析和差异比较分析。最后使用FunGuild数据库对真菌群落进行功能注释, 以进一步研究兰科植物根、根际土与根围土中真菌群落的功能类群差异。

2 结果

2.1 兰科植物根与土壤中的真菌多样性与群落结构比较

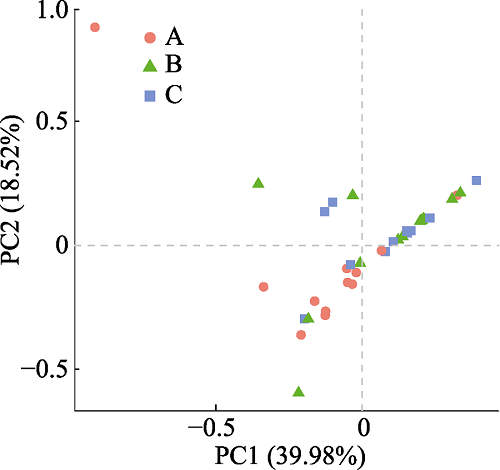

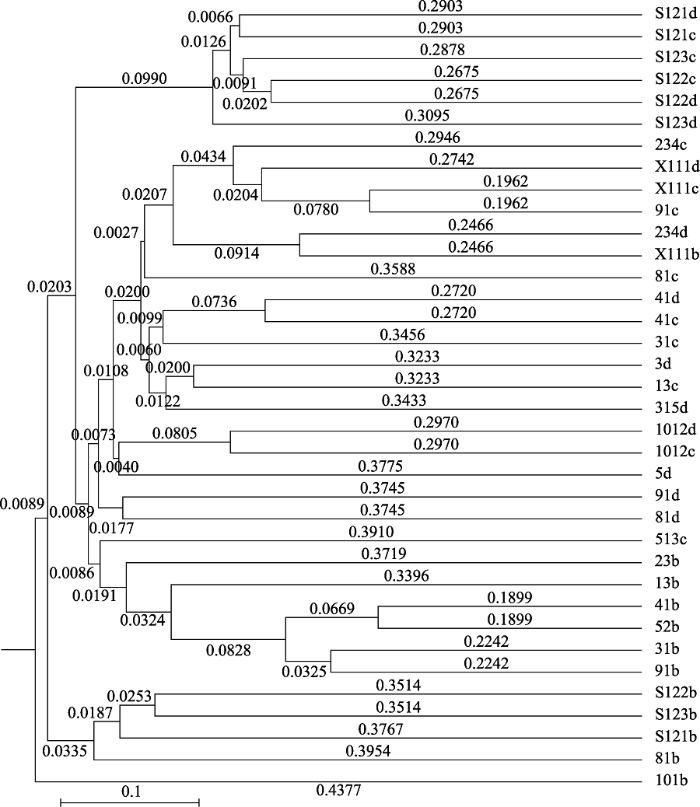

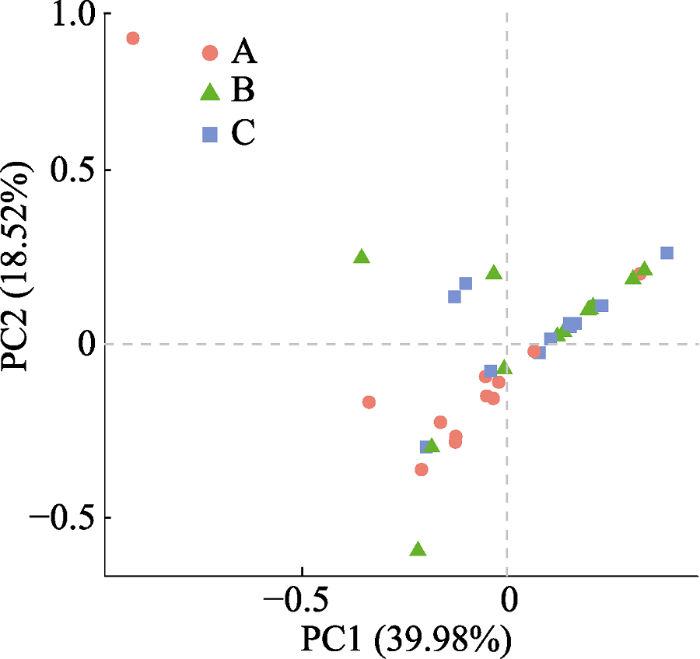

本次实验共取了9种兰科植物的根、根际土和根围土样本, 利用第二代测序技术对这3类样本中的真菌群落进行了测序研究, 测序区域为ITS1区, 测序长度在200-300 bp。将已鉴定出的非真菌序列除去之后, 我们计算了各样本的真菌α多样性指数(包括Chao1、ACE、Shannon和Simpson多样性指数), 各植物根与根际土和根围土之间的Jaccard Index、Unweighted Unifrac Metric和Weighted Unifrac Metric。结果表明, 有的兰科植物根中的真菌多样性和丰富度均小于土壤中的真菌多样性和丰富度, 比如珊瑚兰、头蕊兰、小斑叶兰和绶草, 但有的兰科植物根内的真菌多样性和丰富度要明显高于土壤样本, 如羊耳蒜。因此, 兰科植物根中真菌的多样性与丰富度和兰科植物的种类有关。同时, 各植物根与根际土中真菌群落之间的Jaccard Index在0.177-0.385之间, 平均为0.283; Unweighted Unifrac在0.671-0.903之间, 平均为0.772; Weighted Unifrac在0.78以上, 平均为1.305。根与根围土中的真菌群落之间的Jaccard Index在0.144-0.389之间, 平均为0.273; Unweighted Unifrac在0.694-0.907之间, 平均为0.782; Weighted Unifrac距离在0.98以上, 平均为1.408。基于Unweighted Unifrac距离的adonis分析(p = 0.004)和anosim分析(p = 0.013)也显示根、根际土与根围土的真菌群落具有显著差异, 这表明, 各植物根与根际土、根围土中的真菌群落之间都有很大差异。在PCA分析(图1)、属水平群落组成聚类热图与UPGMA聚类分析(图2)中, 大部分根样本中的真菌群落都聚到了一起, 几乎所有兰科植物根中的真菌群落都和对应的根际土与根围土中的真菌群落相分离。这表明, 本实验中所涉及的9种兰科植物的根和周围土壤中的真菌群落都具有十分明显的差异。这些差异主要体现在真菌的种类和丰度上, 比如, 在小斑叶兰根中丰度较高的一些真菌, 虽然在其土壤中也存在, 但其存在数量极小, 如Phomopsis和Nectriaceae, 同样, 有的在土壤中存在数量较多的真菌在根中存在的数量也很少。

图1

新窗口打开|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT

新窗口打开|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT图1辽宁九种兰科植物根与土壤中真菌群落的主成分分析(PCA)。A, 根样; B, 根际土; C, 根围土样本。

Fig. 1Principal Component Analysis (PCA) of fungal communities in roots and soils of nine orchids in Liaoning, China. A, root; B, rhizosphere soil; C, bulk soil.

图2

新窗口打开|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT

新窗口打开|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT图2基于Unifrac距离的辽宁9种兰科植物根与土壤中真菌群落的UPGMA聚类分析。样本根据彼此之间的相似度聚类, 样本间的分枝长度越短越相似。b, 根; c, 根际土; d, 根围土。右列大写字母及数字代表样本编号。

Fig. 2UPGMA clustering analysis of fungal communities in roots and soils of nine orchids in Liaoning, China based on Unifrac distance. Samples are clustered according to their similarity, and shorter branching length means more similar. b, root; c, rhizosphere soil; d, bulk soil. Uppercase letters and number in right column indicate sample number.

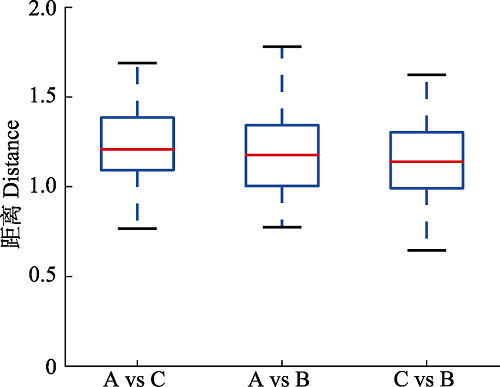

同时, 在PCA与UPGMA聚类分析的结果中我们可以明显地看到, 虽然根际土和根围土样本中的真菌群落与根中的有所分开, 但根际土与根围土之间却并没有明显分离的现象, 这表明, 根际土与根围土样本之间并没有明显差异。但是, 基于Unifrac距离, 利用t检验与蒙特卡洛置换检验对各样本中的真菌群落进行差异比较分析后显示(图3), 兰科植物根与根围土中真菌群落的差异显著大于根围土与根际土之间的差异(p = 0.003), 且根与根际土真菌群落之间的差异要略小于根与根围土。

图3

新窗口打开|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT

新窗口打开|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT图3基于Unifrac距离的根与土壤中真菌群落的差异比较分析。A, 根样; B, 根际土; C, 根围土样本。

Fig. 3Comparative analysis of differences in the fungal communities of roots and soils based on Unifrac distance. A, root; B, rhizosphere soil; C, bulk soil.

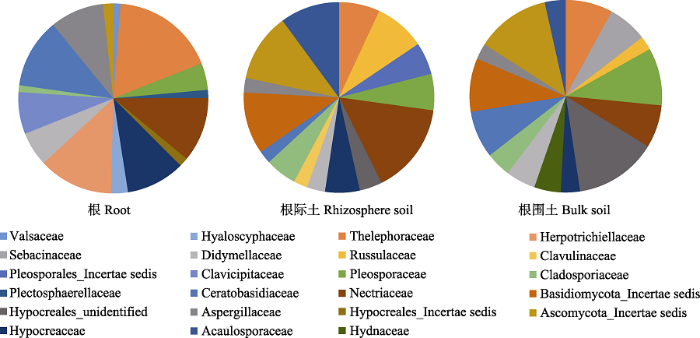

2.2 兰科植物根、根际土与根围土中的真菌群落 组成

测序结果显示, 在剔除所有被鉴定为非真菌序列的序列后, 余下的序列中, 1.40%属于壶菌门(Chytridiomycota), 15.29%属于担子菌门(Basidiomycota), 37.36%属于子囊菌门(Ascomycota), 而其余真菌45.95%的序列在GenBank中都没有明确的鉴定结果。本研究共从除山兰与一株二叶舌唇兰样本以外的所有兰科植物的根中测得3 738个OTU, 根际土中测得5 778个OTU, 根围土中测得6 106个OTU。由于目前真菌数据库的局限性, 所有样本中都有较多分类地位未定的真菌(Incertae_sedis)。除了根、根际土和根围土样本中都存在的大量Incertae_sedis, 兰科植物根中相对丰度最大的真菌为Thelephoraceae (11.63%), 其次则是Herpotrichiellaceae (8.33%)、Ceratobasidiaceae (7.78%)、Nectriaceae (7.23%)和Hypocreaceae (6.57%)等。而根际土中, 相对丰度最大的真菌是Nectriaceae (6.07%), 其次是许多属于Ascomycota的未分类真菌(4.55%)、属于Basidiomycota的未分类真菌(4.14%)、Acaulosporaceae (3.96%), 以及Russulaceae (3.38%), 其中未分类Ascomycota真菌、未分类Basidiomycota真菌、Acaulosporaceae, 以及Russulaceae在兰科植物根中的相对丰度都非常低, 分别为1.12%、0.14%、0.002%和1.05%。同时, 在根围土样本中, 丰度最大的真菌是属于Hypocreales的未鉴定出明确种类的真菌类群, 相对丰度为5.14%, 但这类真菌类群在根际土与根中的相对丰度都很低, 分别为0.02%和1.51%, 其次是在根际土中也大量存在的未分类Ascomycota (4.60%)和未分类Basidiomycota (3.32%), 以及Pleosporaceae (3.57%)和Thelephoraceae (2.93%)。在科的水平上, 每种样本中丰度前15的真菌类群(优势真菌)如图4所示, 可以看出, 根际土与根围土中的优势真菌组成有较高的相似度, 且与根际土中的优势真菌组成有较大差异。

图4

新窗口打开|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT

新窗口打开|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT图4辽宁九种兰科植物根、根际土与根围土中丰度前15的真菌类群。

Fig. 4Top 15 fungi in root, rhizosphere soil and bulk soil of nine orchids in Liaoning, China.

2.3 功能预测分析

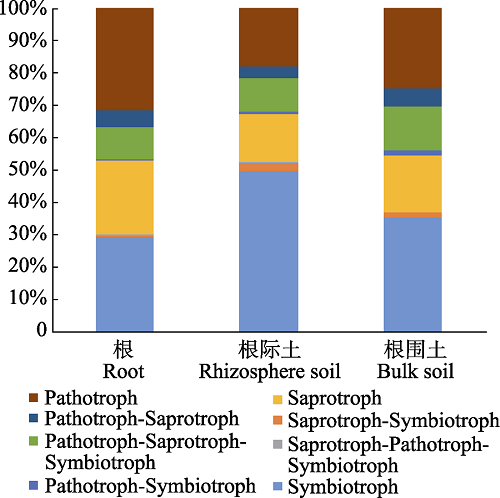

FunGuild是一个用于真菌功能注释的数据库, 目前涵盖了超过12 000个真菌的功能注释信息。为了保证数据分析的准确性, 我们去除了10条序列以下的OTU, 在FunGuild数据库中对剩下的2 855个OTU进行了注释, 但由于FunGuild数据库中数据的有限性, 仅有944个OTU有匹配结果, 其中, 准确性为极可能(Highly Probable)与很可能(Probable)的OTU共有704个, 为了保证数据分析结果的可靠性与完整性, 我们对准确率为极可能与很可能的数据进行了分析。兰科植物根、根际土与根围土中的营养方式组成情况如图5所示。根际土与根围土中Pathotroph、Saprotroph和Symbiotroph的OTU数目明显多于兰科植物的根, 但其他营养方式真菌的OTU数目在3种样本中没有明显差异。

图5

新窗口打开|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT

新窗口打开|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT图5辽宁九种兰科植物根、根际土与根围土中真菌的营养方式组成。

Fig. 5Trophic mode of fungi in orchid’s root, rhizosphere soil and bulk soil of nine orchids in Liaoning, China.

兰科植物根、根际土与根围土中真菌的功能型组成情况如图6所示, Ectomycorrhizal、Plant Pathogen和Saprotroph在3种样本中均占主要地位, 不过, 在根际土与根围土样本中的Arbuscular Mycorrhizal, 在兰科植物根中的丰度非常低。

图6

新窗口打开|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT

新窗口打开|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT图6辽宁九种兰科植物根、根际土与根围土中真菌功能型组成。

Fig. 6Guild of fungi in orchid’s root, rhizosphere soil and bulk soil of nine orchids in Liaoning Province, China.

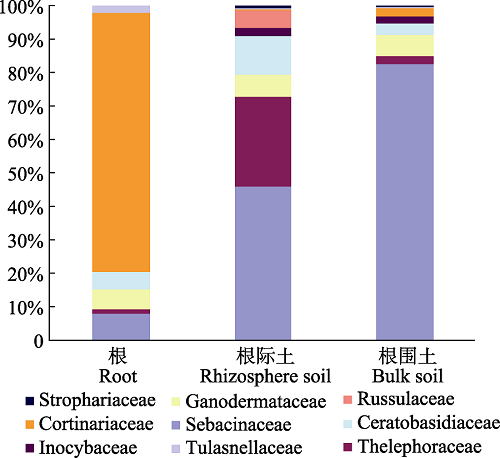

2.4 兰科植物菌根真菌在根与土壤中的分布

根据Dearnaley等(2012)对兰科菌根真菌的介绍与总结, 及其他多篇相关研究, 筛选出了存在于各兰科植物根中的菌根真菌。我们分析了菌根真菌在根与土壤中的存在情况, 结果显示, 二叶舌唇兰根中的菌根真菌, 如Ceratobasidiaceae、Tulasnellaceae、Gymnomyces和Epulorhiza等, 在其对应的根际土与根围土样本中却几乎没有。反之, 在二叶舌唇兰的根际土与根围土中大量存在的Russula和Thelephoraceae在根中也几乎没检测到。同样, 山兰的土壤样本中含有Thelephoraceae、Ceratobasidiaceae、Tuber等多种菌根真菌, 而其根内却只存在Ceratobasidium, 珊瑚兰的土壤中也有较多的Sebacinaceae、Russula和Tuberaceae, 但其根内却以Thelephoraceae为主, 其余菌根真菌含量极少; 长苞头蕊兰根中的菌根真菌主要是Sebacinaceae, 但Sebacinaceae在土壤中的含量却很少, 且土壤中的主要菌根真菌是Ceratobasidiaceae和Russula; 细葶无柱兰的主要菌根真菌Ceratobasidiaceae在根中的丰度远高于其在周围土壤中的丰度; 蜻蜓兰的根中测得的菌根真菌丰度极低, 仅有0.47%的Thelephoraceae序列与0.17%的Ceratobasidiaceae序列, 但蜻蜓兰的根围土和根际土样本中却存在大量的Thelephoraceae和Sebacinaceae等菌根真菌。

和以上的所有样本一样, 本实验中采于同一生境的绶草根内的菌根真菌群落与根际土、根围土样本中菌根真菌群落的也具有明显差别, 如图7所示。

图7

新窗口打开|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT

新窗口打开|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT图7辽宁绶草根、根际土与根围土中的菌根真菌群落比较。

Fig. 7Comparison of mycorrhizal fungi Spiranthes sinensis’s root, rhizosphere soil and bulk soil in Liaoning.

由此可见, 这几种兰科植物根和它们周围土壤中的菌根真菌群落存在明显差异, 且根与周围土壤中的菌根真菌群落之间没有明显联系。

3 讨论

众所周知, 菌根真菌对兰科植物的生存是必需的。然而, 本研究利用高通量测序技术对9种兰科植物根中的真菌群落进行全面分析后却发现, 本研究所涉及的8种陆生兰科植物的根中, 绝大部分真菌都是非菌根真菌, 菌根真菌只占了很少一部分。这种兰科植物根内菌根真菌丰度过低的情况, 可能是中国东北地区兰科植物极稀少的原因之一, 即菌根真菌丰度太低, 兰科植物的种子无法得到足够的营养物质, 不能成功萌发。其中, 作为腐生兰科植物的珊瑚兰根中的真菌以外生菌根真菌Thelephoraceae为主, 且丰度高达99.39%, 与以往关于珊瑚兰菌根真菌的研究结果相符合(McKendrick et al., 2000; Zimmer et al., 2008)。这是由于珊瑚兰无绿叶, 属于腐生小草本, 是完全异养型兰科植物, 必须要依靠菌根真菌为其提供营养, McKendrick等(2000)的实验便证明, 标记了14C的光合产物通过外生菌根从珊瑚兰周围的树中流向了珊瑚兰, 这表明, 作为外生菌根真菌的Thelephoraceae真菌会从其他植物中获得营养并输送给珊瑚兰, 以维持珊瑚兰生长。同时, 随着人们对兰科植物菌根真菌研究的深入, 越来越多的研究发现兰科植物菌根真菌会受到宿主生育期的强烈影响, 比如常见的药用兰科植物天麻(Gastrodia elata)在种子时期, 共生菌根真菌为小菇属真菌(如Mycena osmundicola), 而成熟后, 共生菌根真菌却不再是小菇属真菌, 而变成了蜜环菌(Armillaria mellea), 且蜜环菌的代谢产物会抑制天麻种子的萌发(冉砚珠和徐锦堂, 1988)。Bidartondo和Read (2008)研究了Cephalanthera damasonium、 Cephalanthera longifolia和Epipactis atrorubens这3种兰科植物在种子萌发期、幼苗生长期和成熟期的共生菌根真菌, 结果表明C. damasonium和C. longifolia这2种兰科植物均会随着种子的萌发生长, 改变共生菌根真菌的种类。不过, 如表1所示, 由于东北地区兰科植物的稀有性, 我们在本研究中只采集到了营养期与花期的菌根样本, 其余生育期的兰科植物菌根样本还未收集到, 因此本次的数据还不足以反映出生育期对兰科植物菌根真菌的影响, 在后续的实验中, 我们将收集同种植物在不同生育期中的菌根样本, 以全面研究生育期对兰科植物菌根真菌的影响。

本研究在研究兰科植物根中菌根真菌的同时, 也对兰科植物根中的非菌根真菌进行了分析。我们将序列数在10条以上的OTU在FunGuild数据库进行了功能预测分析, 结果显示, 根、根际土和根围土中的真菌群落都主要由营养类型为Saprotroph、Pathotroph、Symbiotroph和Pathotroph-Saprotroph- Symbiotroph的真菌为主, 其他营养类型的真菌数量较少。而从功能类型上看, 兰科植物根中真菌的功能类型主要为Saprotroph、Plant Pathogen和Ectomycorrhizal, 而根际土和根围土中真菌功能类型除Saprotroph、Plant Pathogen和Ectomycorrhizal以外, 还包括了数量较多的丛枝菌根真菌。但这些丛枝菌根真菌却几乎不存在于兰科植物的根中, 这可能与兰科植物对共生菌根真菌的特异性有关, 即兰科植物只能和兰科菌根真菌形成菌根, 而不能和其他类型的菌根真菌形成菌根关系。因此, 即使丛枝菌根真菌在根际土与根围土中的丰度非常高, 但在兰科植物的根中仍然数量极少。

另一方面, 本研究从兰科植物根中测得的OTU个数远低于从根际土和根围土中测得的OTU个数。这表明, 兰科植物根中的真菌类群种类数远少于根际土和根围土, 即根际土和根围土中的真菌组成比兰科植物根中的真菌组成要更复杂。同时, 我们利用adonis、anosim、PCA和UPGMA聚类分析等分析方法对兰科植物根、根际土和根围土中真菌群落结构进行了分析, 发现兰科植物根中的真菌群落和根际土、根围土中的真菌群落在组成与结构上都具有显著差异。最明显的差异体现在优势真菌的组成上。如之前的分析结果所示, 兰科植物根中的优势真菌种类和根际土与根围土差异较大, 而根际土与根围土中的优势真菌组成却具有较高的相似度, 这表明, 在真菌群落的组成上, 兰科植物根中的真菌群落与根际土中的真菌群落并无强烈联系。

在兰科植物根、根际土和根围土中的菌根真菌组成上, 结果显示, 许多在兰科植物根中丰度较大的菌根真菌在根际土和根围土中却呈现出零星分布的情况, 即兰科植物根中的菌根真菌群落与根际土和根围土中的菌根真菌群落都没有明显联系。相似的结果在Liu等(2015)、Oja等(2015)和Han等(2016)的研究中也有报道。但也有很多研究表明, 大部分在根中发现的菌根真菌在土壤中也广泛分布, 且随着离宿主植物距离的增加, 相应的菌根真菌多样性和丰度逐渐减少(McCormick et al., 2012; Waud et al., 2016)。不过, 这类结果多数是由种子萌发实验得出的。一些通过研究兰科植物种子萌发来研究兰科植物与菌根真菌的关系的研究显示, 兰科植物种子的萌发和其成熟植物的空间分布有一定联系(Jacquemyn et al., 2007)。随着离成熟兰科植物距离的增加, 其种子的萌发率会逐渐减少, 这表明, 土壤中适宜菌根真菌的丰度也在随距离的增加而减少(Batty et al., 2001; Diez, 2007)。比如,Waud等(2016)用分子技术也证明了兰科植物周围土壤中的菌根真菌随与植物的距离增加而减少的现象。但在Waud等(2017)的另一个研究中, 他们对双叶兰的种子萌发进行的研究中, 发现双叶兰种子的萌发率在有成熟双叶兰植株的地点和没有双叶兰植株存在的地点相差无几, 反而土壤中的水分含量对双叶兰种子萌发有显著影响。

根据本研究与以往相关研究的结果, 可见, 目前关于兰科植物根与土壤中菌根真菌关系的研究结果出现的分歧, 首先可能是由于实验方法的不同。在种子萌发类研究中, 影响种子萌发的因素除了菌根真菌之外还有很多, 比如土壤中有机物质和物理化学性质, 因此, 菌根真菌可能并不是兰科植物种子萌发的决定性因素(Waud et al., 2017)。甚至还有研究证明, 有的成熟兰科植物根内的菌根真菌并不能促进该种兰科植物的种子萌发, 比如, 天麻种子必须与小菇属真菌(如Mycena osmundicola)共生才能成功萌发, 而天麻的成熟植株却偏好与蜜环菌共生, 且蜜环菌的代谢产物会严重抑制天麻种子的萌发(徐锦堂, 2013)。而在高通量测序研究中, 能够影响实验结果的因素也很多, 比如取样规则、引物选择、实验材料处理、测序深度等。同时, 这两种研究方法所涉及的兰科植物生育期也不相同, 前者主要针对兰科植物的种子时期, 而后者的实验对象则通常是成熟兰科植物。其次, 这种分歧的出现还有可能和植物种类有关(Waud et al., 2016), 不同兰科植物对其共生菌根真菌的特异性不同, 有的兰科植物可以与多种共生菌根真菌共生, 而有的兰科植物却只能和特定的一种菌根真菌共生, 如珊瑚兰只和Thelephoraceae共生。最后, 环境因素对菌根真菌的群落组成也有强烈影响(Kartzinel et al., 2013; Oja et al., 2015; Esposito et al., 2016; Cevallos et al., 2017)。因此这种分歧的出现还可能和进行实验的时期、地点等环境因素有关, 比如, Anacamptis morio根内的Tulasnella在秋季和冬季多, 而Ceratobasidium则在夏季更多(Ercole et al., 2015)。

4 结论

本研究利用高通量测序技术对兰科植物根、根际土和根围土中的真菌群落进行了研究。研究结果表明, 兰科植物根中的真菌群落与根际土、根围土中的真菌群落具有显著差异, 兰科植物根中的总OTU数目远小于根际土和根围土中的总OTU数目, 真菌群落组成远不如两种土壤样本中的真菌组成复杂。同时, 兰科植物根中菌根真菌的种类和丰度与根际土或根围土中菌根真菌的种类与丰度没有明显联系。FunGuild分析结果也显示, 丛枝菌根真菌在根际土与根围土中的丰度非常高, 但在兰科植物的根中却数量极少。这些结果表明, 兰科植物根中的真菌群落与土壤中的真菌群落在一定程度上是相互独立的。另外, 在本次研究中, 我们从兰科植物根、根际土和根围土中测得了足够的序列量, 但在NCBI数据库中却有较大比例的序列无法比对到相应的真菌信息。同时, 当我们用Unite数据库比对获得的ITS序列, 却发现很多植物本身的信息被比对为了真菌信息(比如绶草的ITS序列被鉴定为Sarcodon atroviridis), 极大地干扰了研究的进行。此外, 在利用FunGuild对鉴定到的OTU进行功能预测分析时, 得到的可分析数据也很少, 这些情况都表明, 目前人们在真菌的研究上仍然还有许多不足, 需要进一步发展研究方法并开展更为系统深入的研究。

参考文献 原文顺序

文献年度倒序

文中引用次数倒序

被引期刊影响因子

[本文引用: 1]

DOI:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2008.03848.xURLPMID:18627452 [本文引用: 1]

Fungus-subsidized growth through the seedling stage is the most critical feature of the life history for the thousands of mycorrhizal plant species that propagate by means of 'dust seeds.' We investigated the extent of specificity towards fungi shown by orchids in the genera Cephalanthera and Epipactis at three stages of their life cycle: (i) initiation of germination, (ii) during seedling development, and (iii) in the mature photosynthetic plant. It is known that in the mature phase, plants of these genera can be mycorrhizal with a number of fungi that are simultaneously ectomycorrhizal with the roots of neighbouring forest trees. The extent to which earlier developmental stages use the same or a distinctive suite of fungi was unclear. To address this question, a total of 1500 packets containing orchid seeds were buried for up to 3 years in diverse European forest sites which either supported or lacked populations of helleborine orchids. After harvest, the fungi associated with the three developmental stages, and with tree roots, were identified via cultivation-independent molecular methods. While our results show that most fungal symbionts are ectomycorrhizal, differences were observed between orchids in the representation of fungi at the three life stages. In Cephalanthera damasonium and C. longifolia, the fungi detected in seedlings were only a subset of the wider range seen in germinating seeds and mature plants. In Epipactis atrorubens, the fungi detected were similar at all three life stages, but different fungal lineages produced a difference in seedling germination performance. Our results demonstrate that there can be a narrow checkpoint for mycorrhizal range during seedling growth relative to the more promiscuous germination and mature stages of these plants' life cycle.

DOI:10.1038/nmeth.2276URLPMID:23202435 [本文引用: 1]

High-throughput sequencing has revolutionized microbial ecology, but read quality remains a considerable barrier to accurate taxonomy assignment and α-diversity assessment for microbial communities. We demonstrate that high-quality read length and abundance are the primary factors differentiating correct from erroneous reads produced by Illumina GAIIx, HiSeq and MiSeq instruments. We present guidelines for user-defined quality-filtering strategies, enabling efficient extraction of high-quality data and facilitating interpretation of Illumina sequencing results.

DOI:10.1016/j.mycres.2009.07.007URLPMID:19619652 [本文引用: 1]

Fully subterranean Rhizanthella gardneri (Orchidaceae) is obligately mycoheterotrophic meaning it is nutritionally dependent on the fungus it forms mycorrhizas with. Furthermore, R. gardneri purportedly participates in a nutrient sharing tripartite relationship where its mycorrhizal fungus simultaneously forms ectomycorrhizas with species of Melaleuca uncinata s.l. Although the mycorrhizal fungus of R. gardneri has been morphologically identified as Thanatephorus gardneri (from a single isolate), this identification has been recently questioned. We sought to clarify the identification of the mycorrhizal fungus of R. gardneri, using molecular methods, and to identify how specific its mycorrhizal relationship is. Fungal isolates taken from all sites where R. gardneri is known to occur shared almost identical ribosomal DNA (rDNA) sequences. The fungal isolate rDNA most closely matched that of other Ceratobasidiales species, particularly within the Ceratobasidium genus. However, interpretation of results was difficult as we found two distinct ITS sequences within all mycorrhizal fungal isolates of R. gardneri that we assessed. All mycorrhizal fungal isolates of R. gardneri readily formed ectomycorrhizas with a range of M. uncinata s.l. species. Consequently, it is likely that R. gardneri can form a nutrient sharing tripartite relationship where R. gardneri is connected to autotrophic M. uncinata s.l. by a common mycorrhizal fungus. These findings have implications for better understanding R. gardneri distribution, evolution and the ecological significance of its mycorrhizal fungus, particularly in relation to nutrient acquisition.

URLPMID:23705374 [本文引用: 1]

Based on the identification of the threatened plants in Northeast China and the priority conservation value of plants, the priority conservation regions of the threatened plants in Northeast China were determined. In the 219 counties (or cities) of Northeast China, 119 counties (or cities) had the distribution of threatened plants. The Antu County in Jilin Province had the most species (42) of threatened plants. A total of 16 counties (cities) such as the Antu County of Jilin Province and the Huanren Manchu Autonomous County of Liaoning Provice, etc. were identified as the priority conservation regions of the threatened plants in Northeast China. According to the priority conservation value, five priority conservation regions of threatened plants in Northoast China were divided, including Changbai Mountain conservation region, East Liaoning conservation region, South Liaoning conservation region, Zhangguangcai Mountain conservation region, and Xiaoxing' an Mountain conservation region. The main threatened plants in each priority conservation region were also analyzed.

URLPMID:23705374 [本文引用: 1]

Based on the identification of the threatened plants in Northeast China and the priority conservation value of plants, the priority conservation regions of the threatened plants in Northeast China were determined. In the 219 counties (or cities) of Northeast China, 119 counties (or cities) had the distribution of threatened plants. The Antu County in Jilin Province had the most species (42) of threatened plants. A total of 16 counties (cities) such as the Antu County of Jilin Province and the Huanren Manchu Autonomous County of Liaoning Provice, etc. were identified as the priority conservation regions of the threatened plants in Northeast China. According to the priority conservation value, five priority conservation regions of threatened plants in Northoast China were divided, including Changbai Mountain conservation region, East Liaoning conservation region, South Liaoning conservation region, Zhangguangcai Mountain conservation region, and Xiaoxing' an Mountain conservation region. The main threatened plants in each priority conservation region were also analyzed.

DOI:10.1038/nmeth.f.303URLPMID:20383131 [本文引用: 1]

DOI:10.1007/s00572-016-0746-8URLPMID:27882467 [本文引用: 1]

In epiphytic orchids, distinctive groups of fungi are involved in the symbiotic association. However, little is known about the factors that determine the mycorrhizal community structure. Here, we analyzed the orchid mycorrhizal fungi communities associated with three sympatric Cymbidieae epiphytic tropical orchids (Cyrtochilum flexuosum, Cyrtochilum myanthum, and Maxillaria calantha) at two sites located within the mountain rainforest of southern Ecuador. To characterize these communities at each orchid population, the ITS2 region was analyzed by Illumina MiSeq technology. Fifty-five mycorrhizal fungi operational taxonomic units (OTUs) putatively attributed to members of Serendipitaceae, Ceratobasidiaceae and Tulasnellaceae were identified. Significant differences in mycorrhizal communities were detected between the three sympatric orchid species as well as among sites/populations. Interestingly, some mycorrhizal OTUs overlapped among orchid populations. Our results suggested that populations of studied epiphytic orchids have site-adjusted mycorrhizal communities structured around keystone fungal species. Interaction with multiple mycorrhizal fungi could favor orchid site occurrence and co-existence among several orchid species.

[本文引用: 1]

DOI:10.1093/biomet/80.1.193URL [本文引用: 1]

[本文引用: 1]

[本文引用: 1]

DOI:10.1093/bioinformatics/btq461URLPMID:20709691 [本文引用: 1]

Biological sequence data is accumulating rapidly, motivating the development of improved high-throughput methods for sequence classification.

[本文引用: 1]

DOI:10.1111/nph.13109URLPMID:25382295 [本文引用: 1]

Many adult orchids, especially photoautotrophic species, associate with a diverse range of mycorrhizal fungi, but little is known about the temporal changes that might occur in the diversity and functioning of orchid mycorrhiza during vegetative and reproductive plant growth. Temporal variations in the spectrum of mycorrhizal fungi and in stable isotope natural abundance were investigated in adult plants of Anacamptis morio, a wintergreen meadow orchid. Anacamptis morio associated with mycorrhizal fungi belonging to Tulasnella, Ceratobasidium and a clade of Pezizaceae (Ascomycetes). When a complete growing season was investigated, multivariate analyses indicated significant differences in the mycorrhizal fungal community. Among fungi identified from manually isolated pelotons, Tulasnella was more common in autumn and winter, the pezizacean clade was very frequent in spring, and Ceratobasidium was more frequent in summer. By contrast, relatively small variations were found in carbon (C) and nitrogen (N) stable isotope natural abundance, A. morio samples showing similar (15)N enrichment and (13)C depletion at the different sampling times. These observations suggest that, irrespective of differences in the seasonal environmental conditions, the plant phenological stages and the associated fungi, the isotopic content in mycorrhizal A. morio remains fairly constant over time.

DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0164108URLPMID:27695108 [本文引用: 1]

While it is generally acknowledged that orchid species rely on mycorrhizal fungi for completion of their life cycle, little is yet known about how mycorrhizal fungal diversity and community composition vary within and between closely related orchid taxa. In this study, we used 454 amplicon pyrosequencing to investigate variation in mycorrhizal communities between pure (allopatric) and mixed (sympatric) populations of two closely related Platanthera species (Platanthera bifolia and P. chlorantha) and putative hybrids. Consistent with previous research, the two species primarily associated primarily with members of the Ceratobasidiaceae and, to a lesser extent, with members of the Sebacinales and Tulasnellaceae. In addition, a large number of ectomycorrhizal fungi belonging to various families were observed. Although a considerable number of mycorrhizal fungi were common to both species, the fungal communities were significantly different between the two species. Individuals with intermediate morphology showed communities similar to P. bifolia, confirming previous results based on the genetic architecture and fragrance composition that putative hybrids essentially belonged to one of the parental species (P. bifolia). Differences in mycorrhizal communities between species were smaller in mixed populations than between pure populations, suggesting that variation in mycorrhizal communities was largely controlled by local environmental conditions. The small differences in mycorrhizal communities in mixed populations suggests that mycorrhizal fungi are most likely not directly involved in maintaining species boundaries between the two Platanthera species. However, seed germination experiments are needed to unambiguously assess the contribution of mycorrhizal divergence to reproductive isolation.

[本文引用: 1]

DOI:10.1046/j.1462-2920.2003.00484.xURLPMID:14510843 [本文引用: 1]

Bacterial diversity in 16S ribosomal DNA and reverse-transcribed 16S rRNA clone libraries originating from the heavy metal-contaminated rhizosphere of the metal-hyperaccumulating plant Thlaspi caerulescens was analysed and compared with that of contaminated bulk soil. Partial sequence analysis of 282 clones revealed that most of the environmental sequences in both soils affiliated with five major phylogenetic groups, the Actinobacteria, alpha-Proteobacteria, beta-Proteobacteria, Acidobacteria and the Planctomycetales. Only 14.7% of all phylotypes (sequences with similarities> 97%), but 45% of all clones, were common in the rhizosphere and the bulk soil clone libraries. The combined use of rDNA and rRNA libraries indicated which taxa might be metabolically active in this soil. All dominant taxa, with the exception of the Actinobacteria, were relatively less represented in the rRNA libraries compared with the rDNA libraries. Clones belonging to the Verrucomicrobiales, Firmicutes, Cytophaga-Flavobacterium-Bacteroides and OP10 were found only in rDNA clone libraries, indicating that they might not represent active constituents in our samples. The most remarkable result was that sequences belonging to the Actinobacteria dominated both bulk and rhizosphere soil libraries derived from rRNA (50% and 60% of all phylotypes respectively). Seventy per cent of these clone sequences were related to the Rubrobacteria subgroups 2 and 3, thus providing for the first time evidence that this group of bacteria is probably metabolically active in heavy metal-contaminated soil.

[本文引用: 3]

DOI:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2007.02179.xURLPMID:17888122 [本文引用: 1]

Seed dispersal and the subsequent recruitment of new individuals into a population are important processes affecting the population dynamics, genetic diversity and spatial genetic structure of plant populations. Spatial patterns of seedling recruitment were investigated in two populations of the terrestrial orchid Orchis purpurea using both univariate and bivariate point pattern analysis, parentage analysis and seed germination experiments. Both adults and recruits showed a clustered spatial distribution with cluster radii of c. 4-5 m. The parentage analysis resulted in offspring-dispersal distances that were slightly larger than distances obtained from the point pattern analyses. The suitability of microsites for germination differed among sites, with strong constraints in one site and almost no constraints in the other. These results provide a clear and coherent picture of recruitment patterns in a tuberous, perennial orchid. Seed dispersal is limited to a few metres from the mother plant, whereas the availability of suitable germination conditions may vary strongly from one site to the next. Because of a time lag of 3-4 yr between seed dispersal and actual recruitment, and irregular flowering and fruiting patterns of adult plants, interpretation of recruitment patterns using point patterns analyses ideally should take into account the demographic properties of orchid populations.

DOI:10.1093/aob/mcw015URLPMID:26946528 [本文引用: 2]

In orchid species that have populations occurring in strongly contrasting habitats, mycorrhizal divergence and other habitat-specific adaptations may lead to the formation of reproductively isolated taxa and ultimately to species formation. However, little is known about the mycorrhizal communities associated with recently diverged sister taxa that occupy different habitats.

[本文引用: 1]

[本文引用: 1]

[本文引用: 1]

DOI:10.1111/mec.12481URLPMID:24112409 [本文引用: 1]

The nuclear ribosomal internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region is the formal fungal barcode and in most cases the marker of choice for the exploration of fungal diversity in environmental samples. Two problems are particularly acute in the pursuit of satisfactory taxonomic assignment of newly generated ITS sequences: (i) the lack of an inclusive, reliable public reference data set and (ii) the lack of means to refer to fungal species, for which no Latin name is available in a standardized stable way. Here, we report on progress in these regards through further development of the UNITE database (http://unite.ut.ee) for molecular identification of fungi. All fungal species represented by at least two ITS sequences in the international nucleotide sequence databases are now given a unique, stable name of the accession number type (e.g. Hymenoscyphus pseudoalbidus|GU586904|SH133781.05FU), and their taxonomic and ecological annotations were corrected as far as possible through a distributed, third-party annotation effort. We introduce the term 'species hypothesis' (SH) for the taxa discovered in clustering on different similarity thresholds (97-99%). An automatically or manually designated sequence is chosen to represent each such SH. These reference sequences are released (http://unite.ut.ee/repository.php) for use by the scientific community in, for example, local sequence similarity searches and in the QIIME pipeline. The system and the data will be updated automatically as the number of public fungal ITS sequences grows. We invite everybody in the position to improve the annotation or metadata associated with their particular fungal lineages of expertise to do so through the new Web-based sequence management system in UNITE.

DOI:10.1186/s12864-015-1422-7URLPMID:25886817 [本文引用: 2]

Mycoheterotrophic orchids are achlorophyllous plants that obtain carbon and nutrients from their mycorrhizal fungi. They often show strong preferential association with certain fungi and may obtain nutrients from surrounding photosynthetic plants through ectomycorrhizal fungi. Gastrodia is a large genus of mycoheterotrophic orchids in Asia, but Gastrodia species' association with fungi has not been well studied. We asked two questions: (1) whether certain fungi were preferentially associated with G. flavilabella, which is an orchid in Taiwan and (2) whether fungal associations of G. flavilabella were affected by the composition of fungi in the environment.

DOI:10.1128/AEM.01996-06URLPMID:17220268 [本文引用: 1]

The assessment of microbial diversity and distribution is a major concern in environmental microbiology. There are two general approaches for measuring community diversity: quantitative measures, which use the abundance of each taxon, and qualitative measures, which use only the presence/absence of data. Quantitative measures are ideally suited to revealing community differences that are due to changes in relative taxon abundance (e.g., when a particular set of taxa flourish because a limiting nutrient source becomes abundant). Qualitative measures are most informative when communities differ primarily by what can live in them (e.g., at high temperatures), in part because abundance information can obscure significant patterns of variation in which taxa are present. We illustrate these principles using two 16S rRNA-based surveys of microbial populations and two phylogenetic measures of community beta diversity: unweighted UniFrac, a qualitative measure, and weighted UniFrac, a new quantitative measure, which we have added to the UniFrac website (http://bmf.colorado.edu/unifrac). These studies considered the relative influences of mineral chemistry, temperature, and geography on microbial community composition in acidic thermal springs in Yellowstone National Park and the influences of obesity and kinship on microbial community composition in the mouse gut. We show that applying qualitative and quantitative measures to the same data set can lead to dramatically different conclusions about the main factors that structure microbial diversity and can provide insight into the nature of community differences. We also demonstrate that both weighted and unweighted UniFrac measurements are robust to the methods used to build the underlying phylogeny.

DOI:10.1128/AEM.71.12.8228-8235.2005URLPMID:16332807 [本文引用: 1]

We introduce here a new method for computing differences between microbial communities based on phylogenetic information. This method, UniFrac, measures the phylogenetic distance between sets of taxa in a phylogenetic tree as the fraction of the branch length of the tree that leads to descendants from either one environment or the other, but not both. UniFrac can be used to determine whether communities are significantly different, to compare many communities simultaneously using clustering and ordination techniques, and to measure the relative contributions of different factors, such as chemistry and geography, to similarities between samples. We demonstrate the utility of UniFrac by applying it to published 16S rRNA gene libraries from cultured isolates and environmental clones of bacteria in marine sediment, water, and ice. Our results reveal that (i) cultured isolates from ice, water, and sediment resemble each other and environmental clone sequences from sea ice, but not environmental clone sequences from sediment and water; (ii) the geographical location does not correlate strongly with bacterial community differences in ice and sediment from the Arctic and Antarctic; and (iii) bacterial communities differ between terrestrially impacted seawater (whether polar or temperate) and warm oligotrophic seawater, whereas those in individual seawater samples are not more similar to each other than to those in sediment or ice samples. These results illustrate that UniFrac provides a new way of characterizing microbial communities, using the wealth of environmental rRNA sequences, and allows quantitative insight into the factors that underlie the distribution of lineages among environments.

DOI:10.1007/s00572-011-0404-0URLPMID:21779810 [本文引用: 1]

The seed germination of orchids under natural conditions requires association with mycorrhizal fungi. Dendrobium nobile and Dendrobium chrysanthum are threatened orchid species in China where they are considered medicinal plants. For conservation and application of Dendrobium using symbiosis technology, we isolated culturable endophytic and mycorrhizal fungi colonized in the protocorms and adult roots of two species plants and identified them by morphological and molecular analyses (5.8S and nrLSU). Of the 127 endophytic fungi isolated, 11 Rhizoctonia-like strains were identified as Tulasnellales (three strains from protocorms of D. nobile), Sebacinales (three strains from roots of D. nobile and two strains from protocorms of D. chrysanthum) and Cantharellales (three strains from roots of D. nobile), respectively. In addition, species of Xylaria, Fusarium, Trichoderma, Colletotrichum, Pestalotiopsis, and Phomopsis were the predominant non-mycorrhizal fungi isolated, and their probable ecological roles in the Dendrobium plants are discussed. These fungal resources will be of great importance for the large-scale cultivation of Dendrobium plants using symbiotic germination technology and for the screening of bioactive metabolites from them in the future.

DOI:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2012.05468.xURLPMID:22272942 [本文引用: 3]

Mycorrhizal fungi have substantial potential to influence plant distribution, especially in specialized orchids and mycoheterotrophic plants. However, little is known about environmental factors that influence the distribution of mycorrhizal fungi. Previous studies using seed packets have been unable to distinguish whether germination patterns resulted from the distribution of appropriate edaphic conditions or the distribution of host fungi, as these cannot be separated using seed packets alone. We used a combination of organic amendments, seed packets and molecular assessment of soil fungi required by three terrestrial orchid species to separate direct and indirect effects of fungi and environmental conditions on both seed germination and subsequent protocorm development. We found that locations with abundant mycorrhizal fungi were most likely to support seed germination and greater growth for all three orchids. Organic amendments affected germination primarily by affecting the abundance of appropriate mycorrhizal fungi. However, fungi associated with the three orchid species were affected differently by the organic amendments and by forest successional stage. The results of this study help contextualize the importance of fungal distribution and abundance to the population dynamics of plants with specific mycorrhizal requirements. Such phenomena may also be important for plants with more general mycorrhizal associations.

[本文引用: 1]

[本文引用: 2]

[本文引用: 1]

DOI:10.1111/nph.13223URLPMID:25546739 [本文引用: 3]

Orchid mycorrhizal (OrM) symbionts play a key role in the growth of orchids, but the temporal variation and habitat partitioning of these fungi in roots and soil remain unclear. Temporal changes in root and rhizosphere fungal communities of Cypripedium calceolus, Neottia ovata and Orchis militaris were studied in meadow and forest habitats over the vegetation period by using 454 pyrosequencing of the full internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region. The community of typical OrM symbionts differed by plant species and habitats. The root fungal community of N. ovata changed significantly in time, but this was not observed in C. calceolus and O. militaris. The rhizosphere community included a low proportion of OrM symbionts that exhibited a slight temporal turnover in meadow habitats but not in forests. Habitat differences in OrM and all fungal associates are largely attributable to the greater proportion of ectomycorrhizal fungi in forests. Temporal changes in OrM fungal communities in roots of certain species indicate selection of suitable fungal species by plants. It remains to be elucidated whether these shifts depend on functional differences inside roots, seasonality, climate or succession.

[本文引用: 1]

[本文引用: 1]

DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0076382URLPMID:24146861 [本文引用: 1]

Bacterial and fungal communities associated with plant roots are central to the host health, survival and growth. However, a robust understanding of the root-microbiome and the factors that drive host associated microbial community structure have remained elusive, especially in mature perennial plants from natural settings. Here, we investigated relationships of bacterial and fungal communities in the rhizosphere and root endosphere of the riparian tree species Populus deltoides, and the influence of soil parameters, environmental properties (host phenotype and aboveground environmental settings), host plant genotype (Simple Sequence Repeat (SSR) markers), season (Spring vs. Fall) and geographic setting (at scales from regional watersheds to local riparian zones) on microbial community structure. Each of the trees sampled displayed unique aspects to its associated community structure with high numbers of Operational Taxonomic Units (OTUs) specific to an individual trees (bacteria >90%, fungi >60%). Over the diverse conditions surveyed only a small number of OTUs were common to all samples within rhizosphere (35 bacterial and 4 fungal) and endosphere (1 bacterial and 1 fungal) microbiomes. As expected, Proteobacteria and Ascomycota were dominant in root communities (>50%) while other higher-level phylogenetic groups (Chytridiomycota, Acidobacteria) displayed greatly reduced abundance in endosphere compared to the rhizosphere. Variance partitioning partially explained differences in microbiome composition between all sampled roots on the basis of seasonal and soil properties (4% to 23%). While most variation remains unattributed, we observed significant differences in the microbiota between watersheds (Tennessee vs. North Carolina) and seasons (Spring vs. Fall). SSR markers clearly delineated two host populations associated with the samples taken in TN vs. NC, but overall host genotypic distances did not have a significant effect on corresponding communities that could be separated from other measured effects.

[本文引用: 1]

[本文引用: 1]

[本文引用: 1]

DOI:10.1007/s00572-008-0199-9URL [本文引用: 1]

Pyrola rotundifolia (Ericaceae, Pyroleae tribe) is an understorey subshrub that was recently demonstrated to receive considerable amount of carbon from its fungal mycorrhizal associates. So far, little is known of the identity of these fungi and the mycorrhizal anatomy in the Pyroleae. Using 140 mycorrhizal root fragments collected from two Estonian boreal forests already studied in the context of mixotrophic Ericaceae in sequence analysis of the ribosomal DNA internal transcribed spacer region, we recovered 71 sequences that corresponded to 45 putative species in 19 fungal genera. The identified fungi were mainly ectomycorrhizal basidiomycetes, including Tomentella, Cortinarius, Russula, Hebeloma, as well as some ectomycorrhizal and/or endophytic ascomycetes. The P. rotundifolia fungal communities of the two forests did not differ significantly in terms of species richness, diversity and nutritional mode. The relatively high diversity retrieved suggests that P. rotundifolia does not have a strict preference for any fungal taxa. Anatomical analyses showed typical arbutoid mycorrhizae, with variable mantle structures, uniseriate Hartig nets and intracellular hyphal coils in the large epidermal cells. Whenever compared, fungal ultrastructure was congruent with the molecular identification. Similarly to other mixotrophic and autotrophic pyroloids in the same forests, P. rotundifolia shares its mycorrhizal fungal associates with surrounding trees that are likely a carbon source for pyroloids.

DOI:10.1111/nph.14286URLPMID:27861936 [本文引用: 1]

Mycorrhizal fungi are essential for the survival of orchid seedlings under natural conditions. The distribution of these fungi in soil can constrain the establishment and resulting spatial arrangement of orchids at the local scale, but the actual extent of occurrence and spatial patterns of orchid mycorrhizal (OrM) fungi in soil remain largely unknown. We addressed the fine-scale spatial distribution of OrM fungi in two orchid-rich Mediterranean grasslands by means of high-throughput sequencing of fungal ITS2 amplicons, obtained from soil samples collected either directly beneath or at a distance from adult Anacamptis morio and Ophrys sphegodes plants. Like ectomycorrhizal and arbuscular mycobionts, OrM fungi (tulasnelloid, ceratobasidioid, sebacinoid and pezizoid fungi) exhibited significant horizontal spatial autocorrelation in soil. However, OrM fungal read numbers did not correlate with distance from adult orchid plants, and several of these fungi were extremely sporadic or undetected even in the soil samples containing the orchid roots. Orchid mycorrhizal 'rhizoctonias' are commonly regarded as unspecialized saprotrophs. The sporadic occurrence of mycobionts of grassland orchids in host-rich stands questions the view of these mycorrhizal fungi as capable of sustained growth in soil.

DOI:10.1006/anbo.2000.1162URL [本文引用: 1]

[本文引用: 1]

[本文引用: 1]

[本文引用: 1]

[本文引用: 1]

DOI:10.1111/mec.14014URLPMID:28100022 [本文引用: 2]

What factors determine the distribution of a species is a central question in ecology and conservation biology. In general, the distribution of plant species is assumed to be controlled by dispersal or environmentally controlled recruitment. For plant species which are critically dependent on mycorrhizal symbionts for germination and seedling establishment, specificity in mycorrhizal associations and availability of suitable mycorrhizal fungi can be expected to have a major impact on successful colonization and establishment and thus ultimately on a species distribution. We combined seed germination experiments with soil analyses and fungal assessments using 454 amplicon pyrosequencing to test the relative importance of dispersal limitation, mycorrhizal availability and local growth conditions on the distribution of the orchid species Liparis loeselii, which, despite being widely distributed, is rare and endangered in Europe. We compared local soil conditions, seed germination and mycorrhizal availability in the soil between locations in northern Belgium and France where L.?loeselii occurs naturally and locations where conditions appear suitable, but where adults of the species are absent. Our results indicated that mycorrhizal communities associating with L.?loeselii varied among sites and plant life cycle stages, but the observed variations did not affect seed germination, which occurred regardless of current L.?loeselii presence and was significantly affected by soil moisture content. These results indicate that L.?loeselii is a mycorrhizal generalist capable of opportunistically associating with a variety of fungal partners to induce seed germination. They also indicate that availability of fungal associates is not necessarily the determining factor driving the distribution of mycorrhizal plant species.

[本文引用: 5]

[本文引用: 1]

[本文引用: 1]

DOI:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2007.02362.xURLPMID:18221248 [本文引用: 1]

The leafless, circumboreal orchid Corallorhiza trifida is often assumed to be fully myco-heterotrophic despite contrary evidence concerning its ability to photosynthesize. Here, its level of myco-heterotrophy is assessed by analysing the natural abundance of the stable nitrogen and carbon isotopes (15)N and (13)C, respectively. The mycorrhizal associates and chlorophyll contents of C. trifida were investigated and the C and N isotope signatures of nine C. trifida individuals from Central Europe were compared with those of neighbouring obligate autotrophic and myco-heterotrophic reference plants. The results show that C. trifida only gains c. 52 +/- 5% of its total nitrogen and 77 +/- 10% of the carbon derived from fungi even though it has been shown to specialize on one specific complex of ectomycorrhizal fungi similar to fully myco-heterotrophic orchids. Concurrently, compared with other Corallorhiza species, C. trifida contains a remarkable amount of chlorophyll. Since C. trifida is able to supply significant proportions of its nitrogen and carbon demands through the same processes as autotrophic plants, this species should be referred to as partially myco-heterotrophic.

Constraints to symbiotic germination of terrestrial orchid seed in a mediterranean bushland

1

2001

... 在兰科植物根、根际土和根围土中的菌根真菌组成上, 结果显示, 许多在兰科植物根中丰度较大的菌根真菌在根际土和根围土中却呈现出零星分布的情况, 即兰科植物根中的菌根真菌群落与根际土和根围土中的菌根真菌群落都没有明显联系.相似的结果在

Fungal specificity bottlenecks during orchid germination and development

1

2008

... 同时, 随着人们对兰科植物菌根真菌研究的深入, 越来越多的研究发现兰科植物菌根真菌会受到宿主生育期的强烈影响, 比如常见的药用兰科植物天麻(Gastrodia elata)在种子时期, 共生菌根真菌为小菇属真菌(如Mycena osmundicola), 而成熟后, 共生菌根真菌却不再是小菇属真菌, 而变成了蜜环菌(Armillaria mellea), 且蜜环菌的代谢产物会抑制天麻种子的萌发(

Quality-filtering vastly improves diversity estimates from Illumina amplicon sequencing

1

2013

... 在得到测序数据后, 首先运用QIIME软件(Quantitative Insights Into Microbial Ecology, v1.8.0,

Identity and specificity of the fungi forming mycorrhizas with the rare mycoheterotrophic orchid Rhizanthella gardneri.

1

2009

... 与此同时, 在兰科植物的生长过程中, 土壤中的菌根真菌可以通过多种方式进入兰科植物的根中, 与兰科植物形成共生关系, 比如, 有的菌根真菌通过破坏兰科植物的根被组织或通道细胞侵入兰科植物根的皮层内.据此, 土壤中合适的菌根真菌丰度越大, 则能与生长在该地点的兰科植物形成共生关系的菌根真菌越多, 就越有利于兰科植物的生长.比如,

中国东北受威胁植物的优先保护区域

1

2013

... 中国东北地区位于39.20°-53.92° N, 115.87°- 135.15° E, 处于北半球的中高纬度, 也是中国纬度最高, 气候变化最明显、最敏感的地区(

中国东北受威胁植物的优先保护区域

1

2013

... 中国东北地区位于39.20°-53.92° N, 115.87°- 135.15° E, 处于北半球的中高纬度, 也是中国纬度最高, 气候变化最明显、最敏感的地区(

QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data

1

2010

... 在得到测序数据后, 首先运用QIIME软件(Quantitative Insights Into Microbial Ecology, v1.8.0,

Are there keystone mycorrhizal fungi associated to tropical epiphytic orchids?

1

2017

... 根据本研究与以往相关研究的结果, 可见, 目前关于兰科植物根与土壤中菌根真菌关系的研究结果出现的分歧, 首先可能是由于实验方法的不同.在种子萌发类研究中, 影响种子萌发的因素除了菌根真菌之外还有很多, 比如土壤中有机物质和物理化学性质, 因此, 菌根真菌可能并不是兰科植物种子萌发的决定性因素(

NonparaMetric estimation of the number of classes in a population

1

1984

... 利用QIIME软件, 对OTU丰度矩阵中的每个样本的序列总数在不同深度下随机抽样, 以每个深度下抽取到的序列数及对应的OTU数绘制稀疏曲线, 衡量每个样本的多样性高低.再使用QIIME软件分别计算每个样本的α多样性指数, 包括Simpson多样性指数、Shannon多样性指数、Chao1丰富度估计指数(

Stopping rules and estimation for recapture debugging with unequal failure rates

1

1993

... 利用QIIME软件, 对OTU丰度矩阵中的每个样本的序列总数在不同深度下随机抽样, 以每个深度下抽取到的序列数及对应的OTU数绘制稀疏曲线, 衡量每个样本的多样性高低.再使用QIIME软件分别计算每个样本的α多样性指数, 包括Simpson多样性指数、Shannon多样性指数、Chao1丰富度估计指数(

1

2012

... 根据

Hierarchical patterns of symbiotic orchid germination linked to adult proximity and environmental gradients

1

2007

... 在兰科植物根、根际土和根围土中的菌根真菌组成上, 结果显示, 许多在兰科植物根中丰度较大的菌根真菌在根际土和根围土中却呈现出零星分布的情况, 即兰科植物根中的菌根真菌群落与根际土和根围土中的菌根真菌群落都没有明显联系.相似的结果在

Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST

1

2010

... 在得到测序数据后, 首先运用QIIME软件(Quantitative Insights Into Microbial Ecology, v1.8.0,

Seeking the needle in the haystack: Undetectability of mycorrhizal fungi outside of the plant rhizosphere associated with an endangered Australian orchid

1

2018

... 近年来, 第二代测序技术被广泛应用于微生物群落的研究中,

Temporal variation in mycorrhizal diversity and carbon and nitrogen stable isotope abundance in the wintergreen meadow orchid Anacamptis morio.

1

2015

... 根据本研究与以往相关研究的结果, 可见, 目前关于兰科植物根与土壤中菌根真菌关系的研究结果出现的分歧, 首先可能是由于实验方法的不同.在种子萌发类研究中, 影响种子萌发的因素除了菌根真菌之外还有很多, 比如土壤中有机物质和物理化学性质, 因此, 菌根真菌可能并不是兰科植物种子萌发的决定性因素(

Mycorrhizal fungal diversity and community composition in two closely related Platanthera (Orchidaceae) species

1

2016

... 根据本研究与以往相关研究的结果, 可见, 目前关于兰科植物根与土壤中菌根真菌关系的研究结果出现的分歧, 首先可能是由于实验方法的不同.在种子萌发类研究中, 影响种子萌发的因素除了菌根真菌之外还有很多, 比如土壤中有机物质和物理化学性质, 因此, 菌根真菌可能并不是兰科植物种子萌发的决定性因素(

Cyanide catabolizing enzymes in Trichoderma spp.

1

2002

... 兰科植物根中存在着非常丰富的真菌群落, 我们可以将其分为菌根真菌与非菌根真菌两大类.众所周知, 兰科植物的萌发及后续生长均强烈依赖于其根中的特异性菌根真菌.但也正因如此, 在以往与兰科植物保护有关的研究中, 对于兰科植物根中的菌群, 人们往往只关注菌根真菌, 而忽视了兰科植物根中的非菌根真菌.实际上, 兰科植物根中的非菌根真菌数量也非常庞大, 甚至远多于菌根真菌的数量(

Comparative 16S rDNA and 16S rRNA sequence analysis indicates that Actinobacteria might be a dominant part of the metabolically active bacteria in heavy metal-contaminated bulk and rhizosphere soil.

1

2003

... 采样时, 先用灭菌后的小铲采集植物周围半径5 cm以内的土壤, 装入无菌自封袋中, 放入冰盒暂存, 作为根围土样本; 随后小心地将植物连根拔起, 抖掉根周围松散的土壤, 用灭菌后的剪刀剪取部分植物带土根系, 置于装有0.85% NaCl溶液的25 mL灭菌离心管中, 放入冰盒暂存, 带回实验室后放入冰中30 min, 每隔5 min取出摇匀1次, 然后将根系取出, 将离心管置于离心机中4 000 × g 4 ℃低温离心10 min, 除去上清液, 将得到的土壤沉淀物保存于无菌自封袋中, 于4 ℃冰箱内保存, 作为根际土样本(

Seasonal dynamics of mycorrhizal fungi in Paphiopedilum spicerianum (Rchb. f) Pfitzer—A critically endangered orchid from China.

3

2016

... 与此同时, 在兰科植物的生长过程中, 土壤中的菌根真菌可以通过多种方式进入兰科植物的根中, 与兰科植物形成共生关系, 比如, 有的菌根真菌通过破坏兰科植物的根被组织或通道细胞侵入兰科植物根的皮层内.据此, 土壤中合适的菌根真菌丰度越大, 则能与生长在该地点的兰科植物形成共生关系的菌根真菌越多, 就越有利于兰科植物的生长.比如,

... ), 还是如

... 在兰科植物根、根际土和根围土中的菌根真菌组成上, 结果显示, 许多在兰科植物根中丰度较大的菌根真菌在根际土和根围土中却呈现出零星分布的情况, 即兰科植物根中的菌根真菌群落与根际土和根围土中的菌根真菌群落都没有明显联系.相似的结果在

A spatially explicit analysis of seedling recruitment in the terrestrial orchid Orchis purpurea.

1

2007

... 在兰科植物根、根际土和根围土中的菌根真菌组成上, 结果显示, 许多在兰科植物根中丰度较大的菌根真菌在根际土和根围土中却呈现出零星分布的情况, 即兰科植物根中的菌根真菌群落与根际土和根围土中的菌根真菌群落都没有明显联系.相似的结果在

Differences in mycorrhizal communities between Epipactis palustris, E. helleborine and its presumed sister species E. neerlandica.

2

2016

... 兰科植物根中存在着非常丰富的真菌群落, 我们可以将其分为菌根真菌与非菌根真菌两大类.众所周知, 兰科植物的萌发及后续生长均强烈依赖于其根中的特异性菌根真菌.但也正因如此, 在以往与兰科植物保护有关的研究中, 对于兰科植物根中的菌群, 人们往往只关注菌根真菌, 而忽视了兰科植物根中的非菌根真菌.实际上, 兰科植物根中的非菌根真菌数量也非常庞大, 甚至远多于菌根真菌的数量(

... 属植物共生的植物, 即兰科植物可能会和非兰科植物与同种Helotiales真菌共生(

辽宁省内九种兰科植物菌根真菌多样性研究

1

2018

... 本实验的每种植物都采了叶片、根、根际土和根围土4份样本.其中, 叶片用于提取DNA并扩增ITS1序列, 以精确鉴定植物的种类, 物种鉴定结果如

辽宁省内九种兰科植物菌根真菌多样性研究

1

2018

... 本实验的每种植物都采了叶片、根、根际土和根围土4份样本.其中, 叶片用于提取DNA并扩增ITS1序列, 以精确鉴定植物的种类, 物种鉴定结果如

Highly diverse and spatially heterogeneous mycorrhizal symbiosis in a rare epiphyte is unrelated to broad biogeographic or environmental features

1

2013

... 根据本研究与以往相关研究的结果, 可见, 目前关于兰科植物根与土壤中菌根真菌关系的研究结果出现的分歧, 首先可能是由于实验方法的不同.在种子萌发类研究中, 影响种子萌发的因素除了菌根真菌之外还有很多, 比如土壤中有机物质和物理化学性质, 因此, 菌根真菌可能并不是兰科植物种子萌发的决定性因素(

Towards a unified paradigm for ?sequence-based identification of fungi

1

2013

... 在得到测序数据后, 首先运用QIIME软件(Quantitative Insights Into Microbial Ecology, v1.8.0,

Highly diversified fungi are associated with the achlorophyllous orchid Gastrodia flavilabella.

2

2015

... 与此同时, 在兰科植物的生长过程中, 土壤中的菌根真菌可以通过多种方式进入兰科植物的根中, 与兰科植物形成共生关系, 比如, 有的菌根真菌通过破坏兰科植物的根被组织或通道细胞侵入兰科植物根的皮层内.据此, 土壤中合适的菌根真菌丰度越大, 则能与生长在该地点的兰科植物形成共生关系的菌根真菌越多, 就越有利于兰科植物的生长.比如,

... 在兰科植物根、根际土和根围土中的菌根真菌组成上, 结果显示, 许多在兰科植物根中丰度较大的菌根真菌在根际土和根围土中却呈现出零星分布的情况, 即兰科植物根中的菌根真菌群落与根际土和根围土中的菌根真菌群落都没有明显联系.相似的结果在

Quantitative and qualitative beta diversity measures lead to different insights into factors that structure microbial communities

1

2007

... 使用R软件, 对OTU丰度矩阵中每个样本所对应的OTU总数绘制Specaccum物种累积曲线, 以判断样本量是否足够大; 对丰度前50位的属进行聚类分析, 绘制热图; 对属水平上的群落组成结构进行主成分分析(PCA), 并计算各样本之间的Unweighted Unifrac距离(

Unifrac: A new phylogenetic method for comparing microbial communities

1

2005

... 使用R软件, 对OTU丰度矩阵中每个样本所对应的OTU总数绘制Specaccum物种累积曲线, 以判断样本量是否足够大; 对丰度前50位的属进行聚类分析, 绘制热图; 对属水平上的群落组成结构进行主成分分析(PCA), 并计算各样本之间的Unweighted Unifrac距离(

Non-mycorrhizal endophytic fungi from orchids

1

2015

... 兰科植物根中存在着非常丰富的真菌群落, 我们可以将其分为菌根真菌与非菌根真菌两大类.众所周知, 兰科植物的萌发及后续生长均强烈依赖于其根中的特异性菌根真菌.但也正因如此, 在以往与兰科植物保护有关的研究中, 对于兰科植物根中的菌群, 人们往往只关注菌根真菌, 而忽视了兰科植物根中的非菌根真菌.实际上, 兰科植物根中的非菌根真菌数量也非常庞大, 甚至远多于菌根真菌的数量(

Limitations on orchid recruitment: Not a simple picture

3

2012

... 与此同时, 在兰科植物的生长过程中, 土壤中的菌根真菌可以通过多种方式进入兰科植物的根中, 与兰科植物形成共生关系, 比如, 有的菌根真菌通过破坏兰科植物的根被组织或通道细胞侵入兰科植物根的皮层内.据此, 土壤中合适的菌根真菌丰度越大, 则能与生长在该地点的兰科植物形成共生关系的菌根真菌越多, 就越有利于兰科植物的生长.比如,

... 根内及其周围土壤中的菌根真菌进行研究时, 发现这两种兰科植物周围土壤中的菌根真菌丰度并未随着植物距离的增加而减少, 且菌根真菌的变化与取样地点离成熟兰科植物的距离之间并没有明显的相关性.这些结果使得兰科植物菌根真菌在土壤中的动态分布显得更加神秘, 也带给了我们许多疑问, 比如, 兰科植物菌根真菌在土壤中的分布是否真的和宿主兰科植物的位置有关, 且会随着与兰科植物距离的增加而减少(

... 在兰科植物根、根际土和根围土中的菌根真菌组成上, 结果显示, 许多在兰科植物根中丰度较大的菌根真菌在根际土和根围土中却呈现出零星分布的情况, 即兰科植物根中的菌根真菌群落与根际土和根围土中的菌根真菌群落都没有明显联系.相似的结果在

Germination patterns in three terrestrial orchids relate to abundance of mycorrhizal fungi

1

2016

... 与此同时, 在兰科植物的生长过程中, 土壤中的菌根真菌可以通过多种方式进入兰科植物的根中, 与兰科植物形成共生关系, 比如, 有的菌根真菌通过破坏兰科植物的根被组织或通道细胞侵入兰科植物根的皮层内.据此, 土壤中合适的菌根真菌丰度越大, 则能与生长在该地点的兰科植物形成共生关系的菌根真菌越多, 就越有利于兰科植物的生长.比如,

Symbiotic germination and development of myco-heterotrophic plants in nature: Ontogeny of Corallorhiza trifida and characterization of its mycorrhizal fungi.

2

2000

... 众所周知, 菌根真菌对兰科植物的生存是必需的.然而, 本研究利用高通量测序技术对9种兰科植物根中的真菌群落进行全面分析后却发现, 本研究所涉及的8种陆生兰科植物的根中, 绝大部分真菌都是非菌根真菌, 菌根真菌只占了很少一部分.这种兰科植物根内菌根真菌丰度过低的情况, 可能是中国东北地区兰科植物极稀少的原因之一, 即菌根真菌丰度太低, 兰科植物的种子无法得到足够的营养物质, 不能成功萌发.其中, 作为腐生兰科植物的珊瑚兰根中的真菌以外生菌根真菌Thelephoraceae为主, 且丰度高达99.39%, 与以往关于珊瑚兰菌根真菌的研究结果相符合(

... ).这是由于珊瑚兰无绿叶, 属于腐生小草本, 是完全异养型兰科植物, 必须要依靠菌根真菌为其提供营养,

High diversity of root-associated fungi isolated from three epiphytic orchids in southern Ecuador

1

2018

... 兰科植物根中存在着非常丰富的真菌群落, 我们可以将其分为菌根真菌与非菌根真菌两大类.众所周知, 兰科植物的萌发及后续生长均强烈依赖于其根中的特异性菌根真菌.但也正因如此, 在以往与兰科植物保护有关的研究中, 对于兰科植物根中的菌群, 人们往往只关注菌根真菌, 而忽视了兰科植物根中的非菌根真菌.实际上, 兰科植物根中的非菌根真菌数量也非常庞大, 甚至远多于菌根真菌的数量(

Temporal patterns of orchid mycorrhizal fungi in meadows and forests as revealed by 454 pyrosequencing

3

2015

... 与此同时, 在兰科植物的生长过程中, 土壤中的菌根真菌可以通过多种方式进入兰科植物的根中, 与兰科植物形成共生关系, 比如, 有的菌根真菌通过破坏兰科植物的根被组织或通道细胞侵入兰科植物根的皮层内.据此, 土壤中合适的菌根真菌丰度越大, 则能与生长在该地点的兰科植物形成共生关系的菌根真菌越多, 就越有利于兰科植物的生长.比如,

... 在兰科植物根、根际土和根围土中的菌根真菌组成上, 结果显示, 许多在兰科植物根中丰度较大的菌根真菌在根际土和根围土中却呈现出零星分布的情况, 即兰科植物根中的菌根真菌群落与根际土和根围土中的菌根真菌群落都没有明显联系.相似的结果在

... 根据本研究与以往相关研究的结果, 可见, 目前关于兰科植物根与土壤中菌根真菌关系的研究结果出现的分歧, 首先可能是由于实验方法的不同.在种子萌发类研究中, 影响种子萌发的因素除了菌根真菌之外还有很多, 比如土壤中有机物质和物理化学性质, 因此, 菌根真菌可能并不是兰科植物种子萌发的决定性因素(

蜜环菌抑制天麻种子发芽的研究

1

1988

... 同时, 随着人们对兰科植物菌根真菌研究的深入, 越来越多的研究发现兰科植物菌根真菌会受到宿主生育期的强烈影响, 比如常见的药用兰科植物天麻(Gastrodia elata)在种子时期, 共生菌根真菌为小菇属真菌(如Mycena osmundicola), 而成熟后, 共生菌根真菌却不再是小菇属真菌, 而变成了蜜环菌(Armillaria mellea), 且蜜环菌的代谢产物会抑制天麻种子的萌发(

蜜环菌抑制天麻种子发芽的研究

1

1988

... 同时, 随着人们对兰科植物菌根真菌研究的深入, 越来越多的研究发现兰科植物菌根真菌会受到宿主生育期的强烈影响, 比如常见的药用兰科植物天麻(Gastrodia elata)在种子时期, 共生菌根真菌为小菇属真菌(如Mycena osmundicola), 而成熟后, 共生菌根真菌却不再是小菇属真菌, 而变成了蜜环菌(Armillaria mellea), 且蜜环菌的代谢产物会抑制天麻种子的萌发(

A multifactor analysis of fungal and bacterial community structure in the root microbiome of mature Populus deltoides trees.

1

2013

... 兰科植物根中存在着非常丰富的真菌群落, 我们可以将其分为菌根真菌与非菌根真菌两大类.众所周知, 兰科植物的萌发及后续生长均强烈依赖于其根中的特异性菌根真菌.但也正因如此, 在以往与兰科植物保护有关的研究中, 对于兰科植物根中的菌群, 人们往往只关注菌根真菌, 而忽视了兰科植物根中的非菌根真菌.实际上, 兰科植物根中的非菌根真菌数量也非常庞大, 甚至远多于菌根真菌的数量(

1

2008

... 兰科植物大多数具有极高的药用与观赏价值, 全世界共有28 000种以上, 且所有野生兰科植物均被列入《野生动植物濒危物种国际贸易公约》, 并占该公约所保护植物的90%以上, 毫无疑问, 其是受保护野生植物中的“旗舰”类群.兰科植物的生存与其根中的共生真菌, 尤其是一些特异性菌根真菌高度相关(

东北地区近百年气候变化及突变检测

1

2006

... 中国东北地区位于39.20°-53.92° N, 115.87°- 135.15° E, 处于北半球的中高纬度, 也是中国纬度最高, 气候变化最明显、最敏感的地区(

东北地区近百年气候变化及突变检测

1

2006

... 中国东北地区位于39.20°-53.92° N, 115.87°- 135.15° E, 处于北半球的中高纬度, 也是中国纬度最高, 气候变化最明显、最敏感的地区(

Fungal associates of Pyrola rotundifolia, a mixotrophic Ericaceae, from two Estonian boreal forests.

1

2008

... 兰科植物根中存在着非常丰富的真菌群落, 我们可以将其分为菌根真菌与非菌根真菌两大类.众所周知, 兰科植物的萌发及后续生长均强烈依赖于其根中的特异性菌根真菌.但也正因如此, 在以往与兰科植物保护有关的研究中, 对于兰科植物根中的菌群, 人们往往只关注菌根真菌, 而忽视了兰科植物根中的非菌根真菌.实际上, 兰科植物根中的非菌根真菌数量也非常庞大, 甚至远多于菌根真菌的数量(

Fine-scale spatial distribution of orchid mycorrhizal fungi in the soil of host-rich grasslands

1

2017

... 与此同时, 在兰科植物的生长过程中, 土壤中的菌根真菌可以通过多种方式进入兰科植物的根中, 与兰科植物形成共生关系, 比如, 有的菌根真菌通过破坏兰科植物的根被组织或通道细胞侵入兰科植物根的皮层内.据此, 土壤中合适的菌根真菌丰度越大, 则能与生长在该地点的兰科植物形成共生关系的菌根真菌越多, 就越有利于兰科植物的生长.比如,

Viability testing of orchid seed and the promotion of colouration and germination

1

2000

... 兰科植物根中存在着非常丰富的真菌群落, 我们可以将其分为菌根真菌与非菌根真菌两大类.众所周知, 兰科植物的萌发及后续生长均强烈依赖于其根中的特异性菌根真菌.但也正因如此, 在以往与兰科植物保护有关的研究中, 对于兰科植物根中的菌群, 人们往往只关注菌根真菌, 而忽视了兰科植物根中的非菌根真菌.实际上, 兰科植物根中的非菌根真菌数量也非常庞大, 甚至远多于菌根真菌的数量(

东北地区陆地碳循环平衡模拟分析

1

2001

... 中国东北地区位于39.20°-53.92° N, 115.87°- 135.15° E, 处于北半球的中高纬度, 也是中国纬度最高, 气候变化最明显、最敏感的地区(

东北地区陆地碳循环平衡模拟分析

1

2001

... 中国东北地区位于39.20°-53.92° N, 115.87°- 135.15° E, 处于北半球的中高纬度, 也是中国纬度最高, 气候变化最明显、最敏感的地区(

辽宁省生态功能分区研究

1

2005

... 中国东北地区位于39.20°-53.92° N, 115.87°- 135.15° E, 处于北半球的中高纬度, 也是中国纬度最高, 气候变化最明显、最敏感的地区(

辽宁省生态功能分区研究

1

2005

... 中国东北地区位于39.20°-53.92° N, 115.87°- 135.15° E, 处于北半球的中高纬度, 也是中国纬度最高, 气候变化最明显、最敏感的地区(

Mycorrhizal specificity does not limit the distribution of an endangered orchid species

2

2017

... 在兰科植物根、根际土和根围土中的菌根真菌组成上, 结果显示, 许多在兰科植物根中丰度较大的菌根真菌在根际土和根围土中却呈现出零星分布的情况, 即兰科植物根中的菌根真菌群落与根际土和根围土中的菌根真菌群落都没有明显联系.相似的结果在

... 根据本研究与以往相关研究的结果, 可见, 目前关于兰科植物根与土壤中菌根真菌关系的研究结果出现的分歧, 首先可能是由于实验方法的不同.在种子萌发类研究中, 影响种子萌发的因素除了菌根真菌之外还有很多, 比如土壤中有机物质和物理化学性质, 因此, 菌根真菌可能并不是兰科植物种子萌发的决定性因素(

Specificity and localised distribution of mycorrhizal fungi in the soil may contribute to co-existence of orchid species

5

2016

... 与此同时, 在兰科植物的生长过程中, 土壤中的菌根真菌可以通过多种方式进入兰科植物的根中, 与兰科植物形成共生关系, 比如, 有的菌根真菌通过破坏兰科植物的根被组织或通道细胞侵入兰科植物根的皮层内.据此, 土壤中合适的菌根真菌丰度越大, 则能与生长在该地点的兰科植物形成共生关系的菌根真菌越多, 就越有利于兰科植物的生长.比如,

... ;

... 在兰科植物根、根际土和根围土中的菌根真菌组成上, 结果显示, 许多在兰科植物根中丰度较大的菌根真菌在根际土和根围土中却呈现出零星分布的情况, 即兰科植物根中的菌根真菌群落与根际土和根围土中的菌根真菌群落都没有明显联系.相似的结果在

... ).比如,

... 根据本研究与以往相关研究的结果, 可见, 目前关于兰科植物根与土壤中菌根真菌关系的研究结果出现的分歧, 首先可能是由于实验方法的不同.在种子萌发类研究中, 影响种子萌发的因素除了菌根真菌之外还有很多, 比如土壤中有机物质和物理化学性质, 因此, 菌根真菌可能并不是兰科植物种子萌发的决定性因素(

我国天麻栽培50年研究历史的回顾

1

2013

... 根据本研究与以往相关研究的结果, 可见, 目前关于兰科植物根与土壤中菌根真菌关系的研究结果出现的分歧, 首先可能是由于实验方法的不同.在种子萌发类研究中, 影响种子萌发的因素除了菌根真菌之外还有很多, 比如土壤中有机物质和物理化学性质, 因此, 菌根真菌可能并不是兰科植物种子萌发的决定性因素(

我国天麻栽培50年研究历史的回顾

1

2013

... 根据本研究与以往相关研究的结果, 可见, 目前关于兰科植物根与土壤中菌根真菌关系的研究结果出现的分歧, 首先可能是由于实验方法的不同.在种子萌发类研究中, 影响种子萌发的因素除了菌根真菌之外还有很多, 比如土壤中有机物质和物理化学性质, 因此, 菌根真菌可能并不是兰科植物种子萌发的决定性因素(

The ectomycorrhizal specialist orchid Corallorhiza trifida is a partial myco- heterotroph.

1

2008

... 众所周知, 菌根真菌对兰科植物的生存是必需的.然而, 本研究利用高通量测序技术对9种兰科植物根中的真菌群落进行全面分析后却发现, 本研究所涉及的8种陆生兰科植物的根中, 绝大部分真菌都是非菌根真菌, 菌根真菌只占了很少一部分.这种兰科植物根内菌根真菌丰度过低的情况, 可能是中国东北地区兰科植物极稀少的原因之一, 即菌根真菌丰度太低, 兰科植物的种子无法得到足够的营养物质, 不能成功萌发.其中, 作为腐生兰科植物的珊瑚兰根中的真菌以外生菌根真菌Thelephoraceae为主, 且丰度高达99.39%, 与以往关于珊瑚兰菌根真菌的研究结果相符合(