, 黄小霞, 陈纹, 王镛, 孙坤

, 黄小霞, 陈纹, 王镛, 孙坤西北师范大学生命科学学院, 兰州 730070

Patterns of flower morphology and structural changes during interconversion between chasmogamous and cleistogamous flowers in Viola philippica

LIQiao-Xia , HUANGXiao-Xia, CHENWen, WANGYong, SUNKun

, HUANGXiao-Xia, CHENWen, WANGYong, SUNKun通讯作者:

收稿日期:2017-06-14

接受日期:2017-11-20

网络出版日期:2017-11-10

版权声明:2017植物生态学报编辑部本文是遵循CCAL协议的开放存取期刊,引用请务必标明出处。

基金资助:

展开

摘要

关键词:

Abstract

Methods We used methods of anatomy and structural analysis to observe the morphological structures of flowers under different photoperiods.

Important findings Photoperiod played an important role in the development of CH and CL flowers in V. philippica. Under short-day light and intermediate-day light, both CH and inCL flowers developed simultaneously. Most of the floral buds were CH flowers under a photoperiod of short-day light, but most of the floral buds were inCL flowers under mid-day light. Complete CL flowers formed under long-day lights. However, there were a series of transitional types in the number and morphology of stamens and petals among inCL flowers, including five stamens with three petals related to CH flowers and two stamens with one petal related to CL flowers. The former type was dominant under short-day light conditions, and the latter type was dominant under mid-day light. Further more, there were localized effects in stamen and petal development for CL and inCL flowers. The development of ventral lower petal (corresponding to the lower petal with spur of CH flower) and the adjacent two stamens in inCL flowers were best, and the back petal was similar to that of CL flowers, an organ primordium structure. The adjacent stamens with the back petals tended to be poorly developed. In extreme cases, these stamens in inCL flowers had no pollen sac, only a membranous appendage or even a primordium structure. When the plants with CL or CH flowers were placed under short-day light or long-day light, the newly induced flowers all showed a series of inCL flower types, finally the CL flowers transformed into CH flowers, and the CH flowers transformed into CL flowers. This result indicates the gradual effects of different photoperiods on dimorphic flowers development of V. philippica. A long photoperiod could inhibit the development of partial stamens and petals, and a short photoperiod could prevent the suppression of long-day light and promote the development of stamens and petals.

Keywords:

-->0

PDF (5240KB)元数据多维度评价相关文章收藏文章

本文引用格式导出EndNoteRisBibtex收藏本文-->

开花是被子植物有性繁殖过程中的一个关键阶段, 但不是所有的花都能开放来展示其内部结构, 有些植物的花始终不开放, 通过自花受精产生种子,这种花被称为闭锁花(cleistogamous)。而一些产生闭锁花的植物也能产生开放花(chasmogamous), 能通过远交产生种子。如在禾本科、远志科、凤仙花科、豆科和堇菜科等亲缘关系比较远的开花植物类群中都有闭锁花现象。早在1908年科学家们就描述了30多种植物的开放花与闭锁花形态, 并认为花瓣与雄蕊数量的减少是闭锁花最普遍的特征(Uphof, 1938)。Lord (1981)曾将闭锁花植物分为花前受精闭锁花、假闭花受精闭锁花、完全闭锁花和真正的闭锁花四大类。生物学家与生态学家最感兴趣的是具有两型花的真正闭锁花植物, 即两型的闭花受精植物: 在同一个个体的不同时期或同一时期出现两种形态完全不同的花——开放花与闭锁花。一些生态因子如水分、光强、光周期、土壤营养和温度可能在两型花的形成与发育中起关键作用(Sigrist & Sazima, 2002; Morinaga et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2013)。

两型的闭花受精植物由于闭锁花的完全自交以及开放花的部分自交, 可能会降低居群内或居群间的基因流, 导致自交衰退, 使居群的遗传多样性变低(Auge et al., 2001)。而在具闭锁花的Viola pubescens中, 开放花虽有较高的自交率, 但居群内具较高的遗传多样性, 且居群间的遗传分化也较小, 说明部分异交的开放花对该物种居群遗传多样性的维持起重要作用, 并防止了居群间的遗传分化(Culley & Wolfe, 2001); Impatiens capensis开放花与闭锁花的比率似乎对遗传结构的影响也不大(Paoletti & Holsinger, 1999); Ruellia nudiflora中不同花型对子代的适应性与性能的影响是比较微小的(Munguía-Rosas et al., 2013)。因此, 大多数****认为, 在不断变化的生态环境中, 两型闭花受精植物的开放花与闭锁花是作为一种两头下注的生殖对策以达到繁育系统的优化: 具潜在远交能力的开放花能提供遗传上可变异的子代(Stebbins, 1957; Beattie, 1976; Solbrig, 1976), 降低自交衰退及由生境改变而引起的灭绝风险(Schemske, 1978; Schoen & Lloyd, 1984); 而闭锁花绝对的自交能在远交不利的情况下为植物提供繁殖保障(Schemske, 1978; Campbell, 1982), 保存有利的基因型(Stebbins, 1957; Beattie, 1976; Solbrig, 1976), 防止有害基因渗入(Waller, 1984), 减少因吸引传粉者所需的能量投入(Solbrig, 1976; Schemske, 1978; Waller, 1979), 并在不利的环境下保护花的生殖器官(Campbell, 1982; Campbell et al., 1983)。

堇菜属(Viola)广泛分布在北温带及热带地区的山地森林中(Wahlert et al., 2014), 全球有525-600种, 其中, 80多种具有开放花与闭锁花的混合繁育系统(Culley & Klooster, 2007), 且在一些物种中有形态介于开放花与完全闭锁花之间的过渡闭锁花类型(Lord, 1981; Culley & Klooster, 2007; Li et al., 2016; Malobecki et al., 2016), 个别种类(如Viola odorata)中开放花与闭锁花的诱导与光照时间有关(Mayer & Lord, 1983)。该属植物开放花与闭锁花发育的独特模式已引起了人们的关注(Wang et al., 2013; Li et al., 2016)。为了进一步研究两型花发育的机制, 对其不同类型花的形态结构研究就显得非常必要。

紫花地丁(Viola philippica)为堇菜属多年生草本植物, 是一种典型的具有开放花与闭锁花的两型闭花授精植物。光周期是影响紫花地丁两型花形成的主要生态因子, 短日照下发育的花主要为开放花, 长日照(光周期大于14 h)下形成完全闭锁花(Li et al., 2016)。人们对紫花地丁开放花与完全闭锁花的形态结构已有比较清楚的认识(刘绮丽等, 2006; 王镛等, 2017)。但该物种的开放花与完全闭锁花之间还存在着一种过渡闭锁花(intermediate cleistogamous), 其中, 在短日照下有少数花芽为过渡闭锁花, 中日照下大部分花芽为过渡闭锁花(Li et al., 2016)。那么, 其过渡闭锁花的花芽形态解剖结构如何?有无明显的表型变异?将短日照下的开放花植株置于长日照下或将长日照下的完全闭锁花植株置于短日照下, 新诱导花芽的形态结构是否存在可逆的变化趋势?对这些问题的回答将有助于我们理解紫花地丁开放花到完全闭锁花的变化规律或完全闭锁花到开放花的变化规律, 阐明闭锁花芽中不发育雄蕊与花瓣是否存在位置效应, 并为两型花植物的适应性进化及两型花发育的机制研究提供理论依据。

1 材料和方法

1.1 材料

紫花地丁种子经消毒处理后, 将其种于灭菌处理的营养土中。待种子萌发并长出4-6片真叶后, 将幼苗移栽于含有营养土与蛭石(体积比2:1)的塑料花盆中。设定10 h、12 h和16 h 3个光周期。植株在设有不同光周期(时控器控制光照时间)的不同培养架上平行生长。培养温度在28 ℃左右, 湿度保持在48%左右, 光照强度120 μmol·m-2·s-1左右。大约2个月, 不同光周期下, 植株均被诱导出不同花型的花芽。1.2 实验方法

将不同光周期下诱导的成熟花芽置于OLYMPUS体视显微镜(DP2-BSW-V2.2, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan)下解剖, 并拍照, 得到各种花型的形态结构。不同光周期下, 对开有不同花型(开放花、过渡闭锁花与完全闭锁花芽)的植株数进行统计, 每株摘取2-3个花芽进行形态解剖。同时, 将10 h光周期下已有开放花芽的植株转移到16 h的光周期下或将 16 h光周期下已有完全闭锁花芽的植株转移到10 h的光周期下继续培养, 每隔一段时间对新诱导的花芽进行观察并拍照。与此同时, 对不同花型的花器官进行测量并进行统计。采用爱氏苏木精整体染色法(华中农学院植物教研室植物显微技术组, 1984)对不同花型的花芽进行横切解剖学研究。其具体过程为: 将整个花芽置于爱氏苏木精染色液中室温整体染色3天左右, 用自来水浸洗花芽使其由紫红色变为深蓝色, 用系列乙醇脱水, 二甲苯透明, 浸蜡。花芽横切厚度为 7 μm。利用莱卡光学显微镜(DMI4000B, Leica, Wetzlar, Germany)对石蜡切片进行观察与拍照。

1.3 数据统计分析

用Excel 2007分析误差值并得到柱状图, 不同花型植株所占的百分比以及不同花型花器官大小之间的显著性差异用最小显著差异法进行分析。2 结果和分析

2.1 过渡闭锁花的形态结构

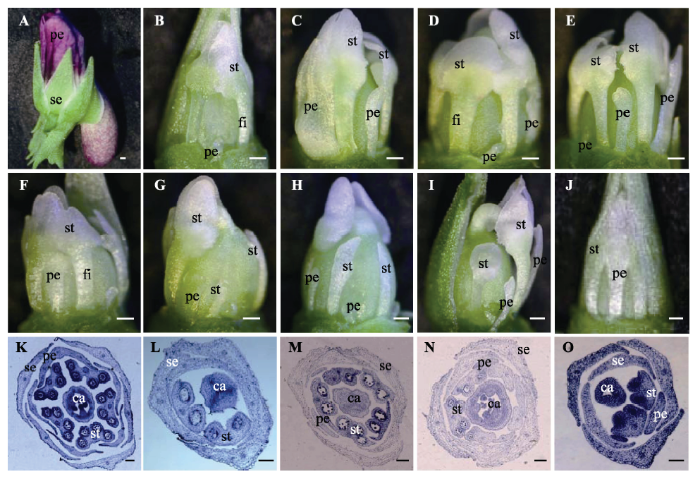

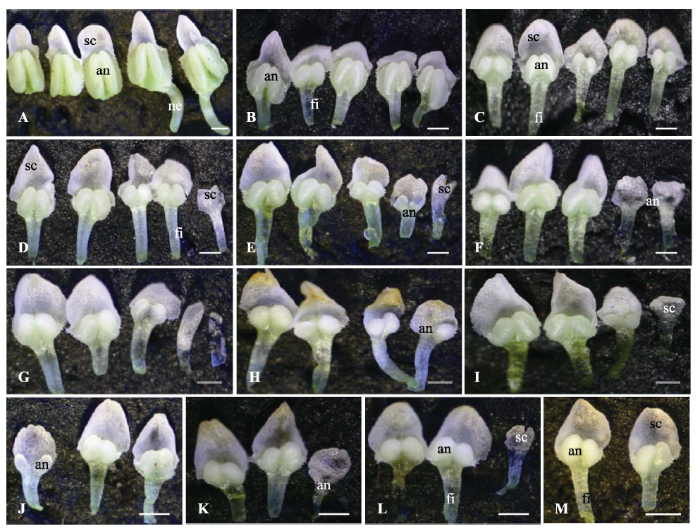

开放花有5个比较大的紫色花瓣, 同时下花瓣基部向后突出形成距; 5枚雄蕊较大, 花丝很短, 几乎看不清, 每个雄蕊有4个花药室(图1A、1K, 图2A), 最下面的2枚雄蕊背基部有明显的蜜腺体并伸向下花瓣形成的距中(图2A)。完全闭锁花5个花瓣均为原基状; 只有2枚雄蕊(花芽的腹侧), 较小, 花丝明显, 每个雄蕊2个花药室, 其余雄蕊(花芽的侧部与背部)均为原基状; 蜜腺体消失(图1B、1L, 图2M)。 显示原图|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT

显示原图|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT图1紫花地丁两型花的表型变异。A, 开放花。B, 完全闭锁花。C-J, 过渡闭锁花。K, 开放花花芽的横切面。L, 完全闭锁花花芽的横切面。M-O, 过渡闭锁花花芽的横切面。ca, 心皮; fi, 花丝; pe, 花瓣; se, 花萼; st, 雄蕊。A-J, 比例尺为500 μm; K, 比例尺为200 μm; L-O, 比例尺为100 μm。

-->Fig. 1The phenotype variation of dimorphic flower in Viola philippica. A, Chasmogamous flower. B, Cleistogamous flower. C-J, Intermediate cleistogamous flower. K, The cross section of chasmogamous flower. L, The cross section of cleistogamous flower. M-O, The cross section of intermediate cleistogamous flower. ca, carpel; fi, filament; pe, petal; se, sepal; st, stamen. A-J, bar = 500 μm; K, bar = 200 μm; L-O, bar = 100 μm.

-->

显示原图|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT

显示原图|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT图2紫花地丁两型花中雄蕊形态与数量的变异。A, 开放花中的5枚雄蕊。B-L, 过渡闭锁花中不同数目的雄蕊。M, 完全闭锁花中的2枚雄蕊。an, 花药; fi, 花丝; sc, 附属结构-雄蕊帽。比例尺为500 μm。

-->Fig. 2The morphological and number variation of stamens in dimorphic flower of Viola philippica. A, The five stamens in chasmogamous flower. B-L, The different number of stamens in intermediate cleistogamous flower. M, The two stamens in cleistogamous flower. an, anther; fi, filament; sc, stamen cap, the membranous appendage structure. Bar = 500 μm.

-->

过渡闭锁花的花瓣在1-3之间, 至少下花瓣有一定的发育(图1C-1J、1M-1O)。比较有趣的是, 在过渡闭锁花中, 与发育比较好的雄蕊相邻的花瓣一般有一定的发育, 尤其是在两枚发育最好的雄蕊间的花瓣往往发育最好, 而与发育不良雄蕊(花药室比较小或只有一个花药室或只为膜质状的雄蕊)相邻的花瓣基本不发育, 为器官原基状(图1C-1J, 图2B-2M)。发育较好的花瓣长度或与雄蕊齐高或为雄蕊的一半且没有花青素的累积(图1C-1J)。

在过渡闭锁花芽中, 雄蕊数目与形态的变化比较大, 花丝明显, 蜜腺体消失, 雄蕊2-5枚, 花药室0-4 (图1C-1J、1M-1O), 只有当雄蕊是5枚的时候, 每个雄蕊的花药室才有4个的可能(图2B)。有的花芽有5枚雄蕊, 但只有2个花药室(图1M, 图2C); 有的花芽虽有5枚可见的雄蕊, 但是部分雄蕊的花药室比较短小, 个别雄蕊只为膜质状结构(图2D-2G); 有的花芽有4枚雄蕊, 个别雄蕊为膜质状结构(图2H、2I); 有的花芽有3枚雄蕊, 个别雄蕊的花药室短小, 或只有一侧有花药室, 个别雄蕊为膜质状结构(图2J-2L); 有的花芽只有2枚雄蕊, 与完全闭锁花的一样(图2M)。因此, 从雄蕊数量上来看, 在过渡闭锁花芽中, 既有接近于开放花的5枚雄蕊, 也有接近于完全闭锁花的2枚雄蕊。

综上, 从过渡闭锁花的形态结构可看出, 与完全闭锁花相似, 雄蕊与花瓣发育的程度似乎有一定的位置效应, 花芽腹侧的下花瓣(对应于开放花有距的下花瓣)与相邻的2枚雄蕊往往发育最好, 而后花瓣(相对于前花瓣)基本与完全闭锁花一样, 为器官原基状, 与后花瓣相邻的2枚雄蕊也发育最小, 而且也最容易发育为无小孢子发生的膜质状结构或原基状结构(图1C-1J, 图2B-2M)。

2.2 不同光周期对过渡闭锁花形态的影响

本次数据与前期研究结果(Li et al., 2016)是一致的, 光周期是紫花地丁两型花形成的主要生态因子。短日照(10 h)下, 大部分植株诱导的花为开放花, 少部分植物诱导的花为过渡闭锁花; 中日照 (12 h)下, 大部分植株开的花为过渡闭锁花, 少部分植株开的花为开放花; 而在长日照(16 h)下, 所有植物诱导的花全为完全闭锁花(表1)。那么, 在短日照与中日照下, 不同类型的过渡闭锁花植株所占的比例有何差异?我们对短日照与中日照下诱导的不同类型过渡闭锁花植株进行了统计。结果发现, 在10 h光照下, 具5枚或4枚雄蕊且有3个花瓣的过渡闭锁花植株在所有植株中占的比例相对较大, 为6.40%, 而具有2枚雄蕊且只有1个花瓣的植株所占比例最小, 为2.10%; 且后者所占比例明显低于前者所占的比例(p < 0.05)(表1)。12 h光照下, 5枚或4枚雄蕊且有3个花瓣的过渡闭锁花植株在所有植株中占的比例为4.70%, 2枚雄蕊且只有1个花瓣的过渡闭锁花植株所占比例为59.57%; 而且后者所占比例明显高于前者所占的比例(p < 0.05)(表1)。由此可见, 10 h与12 h的光周期下, 虽都有过渡闭锁花形成, 但短日照下的过渡闭锁花其花器官数目大多数更接近开放花, 而中日照下的过渡闭锁花其花器官数目更接近于完全闭锁花。Table 1

表1

表1紫花地丁不同光周期对过渡闭锁花形态结构的影响(平均值±标准误差)

Table 1The effect of different photoperiod on the morphological structure of intermediate cleistogamous flowers of Viola philippica (mean ± SE)

| 光周期 Photoperiod (light/dark) | 开放花植株比率 The ratio of plant with CH flowers (%) | 5枚或4枚雄蕊、3个花瓣过渡闭锁花植株比率 The ratio of plant with inCL flowers of 5 or 4 stamens and 3 petals (%) | 3枚雄蕊、3个花瓣过渡闭锁花植株比率 The ratio of plant with inCL flowers of 3 stamens and 3 petals (%) | 2枚雄蕊、3个花瓣过渡闭锁花植株比率 The ratio of plant with inCL flowers of 2 stamens and 3 petals (%) | 2枚雄蕊、1个花瓣过渡闭锁花植株比率 The ratio of plant with inCL flowers of 2 stamens and 1 petal (%) | 完全闭锁花植株比率 The ratio of plant with CL flowers (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 h/14 h | 81.93 ± 0.016d | 6.40± 0.011c | 4.73 ± 0.012c | 4.87 ± 0.006c | 2.10 ± 0.008b | 0.00 ± 0.000a |

| 12 h/12 h | 3.50 ± 0.004b | 4.70 ± 0.014b | 9.27 ± 0.009c | 23.80 ± 0.032d | 59.57 ± 0.008e | 0.00 ± 0.000a |

| 16 h/8 h | 0.00 ± 0.000a | 0.00 ± 0.000a | 0.00 ± 0.000a | 0.00 ± 0.000a | 0.00 ± 0.000a | 100.00 ± 0.000b |

新窗口打开

2.3 开放花植株在长日照下花型的变化趋势

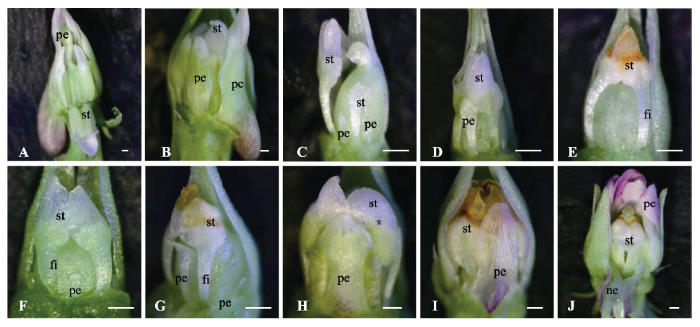

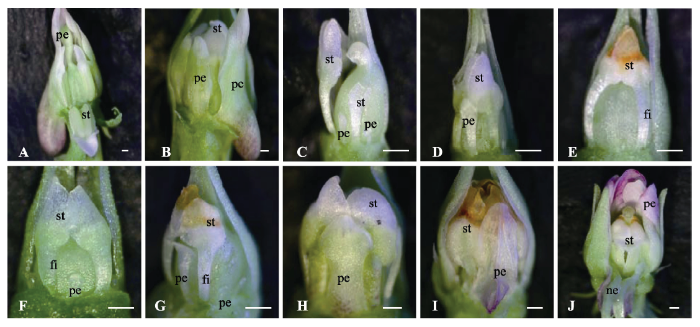

将短日照(10 h)下已有开放花芽的植株移到长日照下(16 h), 每隔一段时间对逐渐诱导出的花芽进行观察、拍照, 并测量花器官的大小(图3A-3E, 图4A、4B)。0天的时候, 花芽为开放花的形态结构(图3A)。10天后, 花的结构为: 5个雄蕊, 每个雄蕊有4个花药室, 雄蕊的蜜腺体消失, 雄蕊的花丝伸长, 为整个雄蕊长度的1/5左右, 花药室变短, 为开放花雄蕊长度的2/3左右; 5个花瓣, 但是花瓣变小, 下花瓣的距变小或消失, 稍高或等高于雄蕊; 柱头弯曲明显(图3B)。20天后, 花的结构为: 有2个发育良好的雄蕊, 每个雄蕊只有2个花药室, 花丝较长, 为整个雄蕊长度的1/2左右, 花药室变得更小, 为开放花雄蕊长度的1/3左右, 其余3个雄蕊为膜质状或丝状结构或为原基状结构; 花瓣更短更窄, 只有2个大雄蕊间的下花瓣较大, 为整个雄蕊长度的3/4, 两个侧瓣较短小, 为雄蕊长度的1/5, 两个后花瓣为原基状; 柱头弯曲(图3C)。30天后, 花的结构为: 2个发育良好的雄蕊, 花丝较长, 花药室较小, 其余3个雄蕊为原基状结构; 只有2个发育较好的雄蕊间的下花瓣呈花瓣状, 为整个雄蕊长度的2/3左右,其余4个花瓣均为原基状结构;柱头弯曲(图3D)。40天后,花芽完全转变为16 h长日照下的完全闭锁花形态结构, 2雄蕊, 花丝较长, 为整个雄蕊长度的1/2左右, 其余3个为原基状; 5个花瓣基本没有发育, 为原基状; 柱头弯曲(图3E)。 显示原图|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT

显示原图|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT图3紫花地丁开放花与完全闭锁花植株在一定光周期下的花型变化趋势。A-E, 具有开放花的植株置于16 h光照时间后花芽形态的变化趋势。A, 0天时的花芽形态。B, 10天时的花芽形态。C, 20天时的花芽形态。D, 30天时的花芽形态。E, 40天时的花芽形态。F-J, 具有完全闭锁花的植株置于10 h光照时间后花芽形态的变化趋势。F, 0天时的花芽形态。G, 20天时的花芽形态。H, 40天时的花芽形态。I, 60天时的花芽形态。J, 80天时的花芽形态。fi, 花丝; ne, 蜜腺体; pe, 花瓣; st, 雄蕊。比例尺500 μm。

-->Fig. 3The variation trends of flowers type of the plants with chasmogamous or cleistogamous flowers under different photoperiod in Viola philippica. A-E, The variation trends of flowers type of the plants with chasmogamous flowers under 16 h daylight. A, The morphological structure of flowers at 0 days. B, The morphological structure of flowers at 10 days. C, The morphological structure of flowers at 20 days. D, The morphological structure of flowers at 30 days. E, The morphological structure of flowers at 40 days. F-J, The variation trends of flowers type of the plants with cleistogamous flowers under 10 h daylight. F, The morphological structure of flowers at 0 days. G, The morphological structure of flowers at 20 days. H, The morphological structure of flowers at 40 days. I, The morphological structure of flowers at 60 days. J, The morphological structure of flowers at 80 days. fi, filament; ne, nectar; pe, petal; st, stamen. Bar = 500 μm.

-->

显示原图|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT

显示原图|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT图4不同光周期下紫花地丁两型花花器官大小的变化趋势。A, B, 开放花植株在16 h日照下新诱导花芽花器官大小的变化趋势。C, D, 完全闭锁花植株在10 h日照下新诱导花芽花器官大小的变化趋势。AnL, 花药的长度; FiL, 花丝的长度; LpeL, 下花瓣的长度; LpeW, 下花瓣的宽度。不同小写字母表示不同时间段下花器官大小之间存在显著差异(p < 0.05)。

-->Fig. 4The variation trends of floral organ size in dimorphic flowers of Viola philippica under different photoperiod. A, B, The variation trends of flowers organ size in newly developed floral buds of the plants with chasmogamous flowers under 16 h daylight. C, D, the variation trends of flowers organ size in newly developed floral buds of the plants with cleistogamous flowers under 10 h daylight. AnL, the length of anther; FiL, the length of filament; LpeL, the length of lower petal; LpeW, the width of lower petal. The different lowercase letters indicated that there were significant differences in the size of floral organs as the time went on (p < 0.05).

-->

在观察花芽形态的同时, 对花器官大小也进行了测量。随着长日照下时间的推移, 雄蕊及花瓣都逐渐变小、变少(图4A、4B)。40天后, 形成了只有2枚雄蕊、花瓣不发育的完全闭锁花(图3E)。

2.4 完全闭锁花植株在短日照下花型的变化趋势

将长日照(16 h)已有完全闭锁花芽的植株移到短日照(10 h)下, 每隔一段时间对逐渐诱导出的花芽进行观察、拍照, 并测量花器官的大小(图3F-3J, 图4C、4D)。0天的时候, 花芽为完全闭锁花的形态结构(图3F)。20天后, 花的结构除下花瓣(比较窄)有一定的发育外, 其余结构与完全闭锁花一致(图3G)。40天后, 花的结构为: 有5个发育良好的雄蕊, 雄蕊有2-4个花药室, 花丝的长度有一定的缩短, 为整个雄蕊长度的1/3左右; 下花瓣有一定的发育, 变的比较宽且有少量花青素的积累(图3H)。60天后, 花的结构为: 5个发育良好的雄蕊, 每个雄蕊都有4个花药室, 花丝进一步缩短, 为整个雄蕊长度的1/4左右, 无蜜腺体; 下花瓣进一步发育, 已有距出现并有花青素的积累; 柱头此时依然弯向2枚大雄蕊(图3I)。80天后, 花芽完全转变为短日照下开放花的形态结构(图3J)。同样, 随着短日照下时间的延长, 雄蕊及花瓣都逐渐变大变多, 而花丝逐渐变短(图4C、4D)。80天后, 形成了有5个紫色花瓣, 且下花瓣有距, 5枚雄蕊, 2枚大雄蕊重新发育有蜜腺体的开放花芽(图3J)。另外, 从不同光周期下花型相互转变的时间可看出, 长日照对雄蕊和花瓣的抑制作用强于短日照对雄蕊和花瓣发育的促进作用。

3 讨论

Li等(2016)的研究表明, 光周期是影响紫花地丁两型花发育的主要生态因子, 短日照下大多数植株被诱导出开放花, 少数植株的花为过渡闭锁花; 中日照下大多数植株的花为过渡闭锁花, 少数为开放花; 长日照下植株被诱导的花全部为完全闭锁花。虽然早在1981年Lord等就描述过Viola odorata在一定光照时间内会存在一种过渡闭锁花类型; Malobecki等(2016)也探讨过Viola uliginosa存在着过渡闭锁花的类型, 但这些研究并没有详细地讨论过渡闭锁花的形态结构及其与开放花和完全闭锁花的关系。在我们的研究中, 我们发现紫花地丁过渡闭锁花是开放花到完全闭锁花或完全闭锁花到开放花的过渡类型, 而且, 这种过渡类型就是一系列具有不同雄蕊与花瓣数目的过渡花芽。比如有最接近于开放花的3个花瓣和5枚雄蕊(每个雄蕊4个花药室)的过渡闭锁花芽, 且这种类型的花芽在短日照的过渡闭锁花芽中所占比例最大; 也有最接近于完全闭锁花的1个花瓣和2枚雄蕊(每雄蕊2个花药室)的过渡闭锁花芽, 这种过渡类型在中日照下所占比例最大。同时, 紫花地丁, 开放花或完全闭锁花植株在长日照或短日照下, 其新诱导的花芽要经历一系列过渡闭锁花的不同类型, 最后发生花型的完全转变。因此, 随着光周期的延长, 长日照能逐步抑制部分花瓣和雄蕊的生长发育, 而短日照能拮抗长日照对雄蕊和花瓣的抑制作用, 使得雄蕊和花瓣破除抑制进而充分发育, 但是长日照的这种抑制作用要强于短日照的拮抗作用。在紫花地丁中, 我们发现完全闭锁花与过渡闭锁花中, 雄蕊与花瓣的发育程度有一定的位置效应, 比如花芽腹侧的雄蕊发育最好, 而背面与侧部的雄蕊发育较弱, 最容易发育为膜质状或原基状结构。Li等(2016)的研究表明, 紫花地丁两型花的形态在花芽发育早期阶段即花器官发生阶段是相似的, 出现差异的时期是在花器官发生以后, 且小孢子发育为产孢细胞后的阶段(王镛等, 2017)。这与一些雌雄异株的植物相似, 如雌雄异体植物Silene latifolia和Rumex acetosa, 雌雄同株植物Cucumis sativus和Platanus acerifolia, 在花发育的早期, 都经历一个雌雄同体阶段, 然而在中后期不同的发育阶段, 性器官会经历不同程度的抑制而最终发育为单性花(Hardenack et al., 1994; Ainsworth et al., 1995; Kater et al., 2001; Li et al., 2012)。在紫花地丁中, 两型花的形态差异也出现在花芽发育的中后期, 部分花器官的发育受到了长日照的抑制作用。当然这种抑制作用可能与长日照影响的某些调控因子有一定的 关系。

笋瓜(Cucurbita maxima)和黄瓜(Cucumis sativus)雌/雄花的雄蕊与雌蕊中均存在赤霉素(GA)含量的不均匀分布, 进而影响雄花或雌花的发育(Lange et al., 2012; Lange & Lange, 2016)。那么, 紫花地丁中, 在完全闭锁花和过渡闭锁花的发育过程中, 雄蕊和花瓣发育的位置效应是否也与某些激素的不对称运输或分布有一定的关系?研究表明, 在两型花植物中, 一些植物激素确实也会影响到两型花的发育。如在Lamium amplexicaule和Collomia grandiflora中, 施加外源GA能诱导闭锁花转变为开放花, 但花药的形态特征仍保持闭锁花的特征(Lord, 1979)。Wang等(2013)研究表明, VGA20oxidase和VGA3oxidase在Viola pubescens开放花中的表达量要高于闭锁花中的表达量。此外, 外源施加ABA几乎使Collomia grandiflora产生全部的闭锁花, Minter和Lord (1983)认为在水胁迫条件下, 更多闭锁花的形成是由于产生了更多的内源ABA。另外, 外源乙烯利能抑制Salpiglossis sinuata两型花花冠的生长, 在传粉之后, 乙烯在开放花和闭锁花中的含量均增加, 但是在闭锁花芽中释放的乙烯更多(Lee et al., 1978)。所以, 在紫花地丁中, 不同的光周期可能也会影响一些激素的合成、分布与运输, 进而引起两型花的发育, 不过这个结论还有待进一步的实验证明。

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

作者声明没有竞争性利益冲突.

参考文献 原文顺序

文献年度倒序

文中引用次数倒序

被引期刊影响因子

| [1] | . |

| [2] | . Abstract We performed demographic and molecular investigations on woodland populations of the clonal herb Viola riviniana in central Germany. We investigated the pattern of seedling recruitment, the amount of genotypic (clonal) variation and the partitioning of genetic variation among and within populations. Our demographic study was carried out in six violet populations of different ages and habitat conditions. It revealed that repeated seedling recruitment takes place in all of these populations, and that clonal propagation is accompanied by high ramet mortality. Our molecular investigations were performed on a subset of three of these six violet populations. Random amplified polymorphic DNA analyses using six primers yielded 45 scorable bands that were used to identify multilocus genotypes, i.e. putative clones. Consistent with our demographic results and independent of population age, we found a large genotypic diversity with a mean proportion of distinguishable genotypes of 0.93 and a mean Simpson diversity index of 0.99. Using amova we found a strong genetic differentiation among these violet populations with a ST value of 0.41. We suggest that a high selfing rate, limited gene flow due to short seed dispersal distances and drift due to founder effects are responsible for this pattern. Although Viola riviniana is a clonal plant, traits associated with sexual reproduction rather than clonality per se are moulding the pattern of genetic variation in this species. |

| [3] | Abstract The effect of pollinator activity on gene flow in colonies of Viola were examined by measuring pollinator flight distances, the frequency of interplant flights and percent pollination under different plant spacing patterns. Pollinator flight distances were directly proportional to spacing parameters while the frequency of interplant flights and percent pollination were inversely proportional to spacing parameters. These findings show that gene flow is reduced by pollinator activity over a wide range of spacing parameters but in populations with low spacing means highly localized gene exchange can occur within the colony. Isolation of colonies may be expected under these circumstaces and cleistogamy may be the optimal breeding system. However, chasmogamous flowers may be important both in promoting within-colony gene exchange and long distance between-colony gene exchange corresponding to the sexual functions proposed in several recent models. Viola colonies appear to be semi-isolated demes with pollinator service which can bring adaptive genes to high localized frequencies, but which maintains low frequency, long-distance gene dispersal. This pattern corresponds to the "Shifting Balance" view of evolution. |

| [4] | |

| [5] | . This field study investigated the task and individual characteristics of 184 professionals who accessed commercial database services to acquire external information directly (as "end users") or through an intermediary ("chauffeur"). Chauffeured access appears to be most appropriate when the individual has a one-time need for new information while direct access appears to be most appropriate when a database is used on a regular basis by the same individual. The results of this study are consistent with prior research which suggests that multiple access arrangements are necessary in order for organizations to make effective use of these and other types of online database systems. |

| [6] | . Cleistogamy, a breeding system in which permanently closed, self-pollinated flowers are produced, has received increasing attention in recent years, but the last comprehensive review of this system was over 20 years ago. The goal of this paper is to clarify the different types of cleistogamy, quantify the number of families, genera, and species in which cleistogamy occurs, and estimate the number of times and potential reasons why cleistogamy has evolved within angiosperms. Cleistogamous species were identified through a literature survey using 13 online databases with references dating back to 1914; only those species well-supported by floral descriptions or empirical data were included in the data set. On the basis of this survey, we suggest the use of three different categories of cleistogamy in future studies: dimorphic, complete, and induced. Based on these categories, cleistogamy in general is present in 693 angiosperm species, distributed over 228 genera and 50 families. When analyzed on a family level across the angiosperms, the breeding system has evolved approximately 34 to 41 times. Theoretical investigations indicate that the evolution of cleistogamy in taxa may be influenced by the presence of heterogeneous environments, inbreeding depression and geitonogamy, and differential seed dispersal, as well as by various ecological factors and plant size. Cleistogamy will undoubtedly be discovered in additional species as the reproductive biology of more taxa is examined in the future. Such information will be invaluable for understanding the selective pressures and factors favoring the evolution of cleistogamy as well as the evolutionary loss of this breeding system, a subject that has received little attention to date. |

| [7] | . Few studies of genetic variation have focused on species that reproduce through both showy, chasmogamous (CH) flowers and self-pollinated, cleistogamous (CL) flowers. Using two different techniques, genetic variation was measured in six populations of Viola pubescens Aiton, a yellow-flowered violet found in the temperate forests of eastern North America. Results from eight allozyme loci showed that there was considerable genetic variation in the species, and population structuring was indicated by the presence of unique alleles and a theta (F(ST)) value of 0.29. High genetic variation was also found using ISSR (inter-simple sequence repeat) markers, and population structuring was again evident with unique bands. Viola pubescens appears to have a true mixed-mating system in which selfing through CL and CH flowers contributes to population differentiation, and outcrossing through CH flowers increases genetic variation and gene flow among populations. Overall, allozyme and ISSR techniques yielded similar results, indicating that ISSR markers show potential for use in population genetic studies. |

| [8] | . Abstract The MADS box motif is common to genes that regulate the pattern of flower development. To determine whether MADS box genes also play a role in differentiation of the sexes in dioecious plants, we isolated cDNAs (SLM1 to SLM5, for Silene latifolia MADS) with MADS box homology from transcripts of male flower buds of the model dioecious species white campion and compared their expression in developing female and male flowers. SLM1 had extensive sequence similarity to the snapdragon MADS box gene PLENA, SLM2 to GLOBOSA, SLM3 to DEFICIENS, and both SLM4 and SLM5 were similar to SQUAMOSA. Each of the white campion MADS box genes was expressed in the same floral whorls as their respective most homologous snapdragon genes. The sex of the plant affected the pattern of SLM2 and SLM3 expression in the petal and stamen whorls, resulting in a smaller fourth whorl in male flowers than in female flowers. This was correlated with repressed gynoecium development in male flowers. The expression of SLM4 and SLM5 in both sexes differed from that of SQUAMOSA in one important aspect. Unlike SQUAMOSA, they were expressed in inflorescence meristems. This may reflect differences in growth pattern between white campion and snapdragon. |

| [9] | . In unisexual flowers, sex is determined by the selective repression of growth or the abortion of either male or female reproductive organs. The mechanism by which this process is controlled in plants is still poorly understood. Because it is known that the identity of reproductive organs in plants is controlled by homeotic genes belonging to the MADS box gene family, we analyzed floral homeotic mutants from cucumber, a species that bears both male and female flowers on the same individual. To study the characteristics of sex determination in more detail, we produced mutants similar to class A and C homeotic mutants from well-characterized hermaphrodite species such as Arabidopsis by ectopically expressing and suppressing the cucumber gene CUCUMBER MADS1 (CUM1). The cucumber mutant green petals (gp) corresponds to the previously characterized B mutants from several species and appeared to be caused by a deletion of 15 amino acid residues in the coding region of the class B MADS box gene CUM26. These homeotic mutants reveal two important concepts that govern sex determination in cucumber. First, the arrest of either male or female organ development is dependent on their positions in the flower and is not associated with their sexual identity. Second, the data presented here strongly suggest that the class C homeotic function is required for the position-dependent arrest of reproductive organs. |

| [10] | . ABSTRACT Gibberellin (GA) signalling during pumpkin male flower development is highly regulated, including biosynthetic, perception, and transduction pathways. GA 20-oxidases, 3-oxidases, and 2-oxidases catalyse the final part of GA synthesis. Additionally, 7-oxidase initiates this part of the pathway in some cucurbits including Cucurbita maxima L. (pumpkin). Expression patterns for these GA-oxidase-encoding genes were examined by competitive reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) and endogenous GA levels were determined during pumpkin male flower development. In young flowers, GA20ox3 transcript levels are high in stamens, followed by high levels of the GA precursor GA9. Later, just before flower opening, transcript levels for GA3ox3 and GA3ox4 increase in the hypanthium and stamens, respectively. In the stamen, following GA3ox4 expression, bioactive GA4 levels rise dramatically. Accordingly, catabolic GA2ox2 and GA2ox3 transcript levels are low in developing flowers, and increase in mature flowers. Putative GA receptor GID1b and DELLA repressor GAIPb transcript levels do not change in developing flowers, but increase sharply in mature flowers. Emasculation arrests floral development completely and leads to abscission of premature flowers. Application of GA4 (but not of its precursors GA12-aldehyde or GA9) restores normal growth of emasculated flowers. These results indicate that de novo GA4 synthesis in the stamen is under control of GA20ox3 and GA3ox4 genes just before the rapid flower growth phase. Stamen-derived bioactive GA is essential and sufficient for male flower development, including the petal and the pedicel growth. |

| [11] | . Gibberellins (GAs) are hormones that control many aspects of plant development, including flowering. It is well known that stamen is the source of GAs that regulate male and bisexual flower development. However, little is known about the role of GAs in female flower development. In cucumber, high levels of GA precursors are present in ovaries and high levels of bioactive GA4 are identified in sepals/petals, reflecting the expression of GA 20-oxidase and 3-oxidase in these organs, respectively. Here, we show that the biologically inactive precursor GA9 moves from ovaries to sepal/petal tissues where it is converted to the bioactive GA4 necessary for female flower development. Transient expression of a catabolic GA 2-oxidase from pumpkin in cucumber ovaries decreases GA9 and GA4 levels and arrests the development of female flowers, and this can be restored by application of GA9 to petals thus confirming its function. Given that bioactive GAs can promote sex reversion of female flowers, movement of biologically inactive precursors, instead of the hormone itself, might help to maintain floral organ identity, ensuring fruit and seed production. |

| [12] | . |

| [13] | . Some plants develop a breeding system that produces both chasmogamous (CH) and cleistogamous (CL) flowers. However, the underlying molecular mechanism remains elusive. In the present study, we observed thatViola philippicadevelops CH flowers with short daylight, whereas an extended photoperiod induces the formation of intermediate CL and CL flowers. In response to long daylight, the respective number and size of petals and stamens was lower and smaller than those of normally developed CH flowers, and a minimum of 14-h light induced complete CL flowers that had no petals but developed two stamens of reduced fertility. The floral ABC model indicates that B-class MADS-box genes largely influence the development of the affected two-whorl floral organs; therefore, we focused on characterizing these genes inV. philippicato understand this particular developmental transition. Three such genes were isolated and respectively designated asVpTM6-1,VpTM6-2, andVpPI. These were differentially expressed during floral development (particularly in petals and stamens) and the highest level of expression was observed in CH flowers; significantly low levels were detected in intermediate CL flowers, and the lowest level in CL flowers. The observed variations in the levels of expression after floral induction and organogenesis apparently occurred in response to variations in photoperiod. Therefore, inhibition of the development of petals and stamens might be due to the downregulation of B-class MADS-box gene expression by long daylight, thereby inducing the generation of CL flowers. Our work contributes to the understanding of the adaptive evolutionary formation of dimorphic flowers in plants. The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s12870-016-0832-2) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users. |

| [14] | . We isolated PaAP3, a homolog of the class B MADS-box transcription factor gene APETALA3 (AP3), from the monoecious plant London plane tree (Platanus acerifolia Willd.). PaAP3 encodes a protein that shares good levels of identity with class B genes from Arabidopsis thaliana (35 and 51 % identity with PISTILLATA (PI) and AP3, respectively), and also with class B genes of other woody species (59 % identity with PTD from Populus trichocarpa and 66 % with TraAP3 from Trochodendron aralioides). Reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction showed that PaAP3 was expressed in both the female and male flowers of P. acerifolia, but almost no signal was detected in the vegetative tissues or mature embryos. The PaAP3 expression in male flowers showed a relationship with developmental stage. There was a small transient increase during differentiation of the flower primordia in June, but maximal levels occurred during December when flower development appeared arrested. Increased PaAP3 expression was also detected in March of the following year, corresponding to meiotic divisions of the microspore mother cells, but this was lost by April when the pollen was mature. |

| [15] | . . 对北京地区一扰动生境中紫花地丁(Viola yedoensis)开放花和闭锁花的产量、结实率和种子质量等繁殖特征进行了比较.开放花在3月初开始开放,雄蕊5枚,具有吸引传粉者开放的花冠等特 征.闭锁花4月初开始形成,雄蕊2枚,且与柱头紧密接触,适应闭花受精.在扰动生境中,紫花地丁个体往往形成更多的闭锁花,而且闭锁花的结实率显著高于开 放花的结实率.所以,大部分种子都是通过闭锁花闭花受精形成的.但是,开放花产生的种子更大,因而可能具有更高的幼苗存活率.即使在不利生境中,闭锁花也 能保障植物繁殖和一定的种子产生.而开放花则产生更多的异交种子以适应新的生境. |

| [16] | . Plants of Lamium amplexicaule, grown under short-day field conditions in Northern California produce predominantly closed flowers. Under long-day field conditions, plants may produce up to 50 per cent open flowers, the same total number of flowers being produced under each daylength regime. A 20 ml drop of GA61 or GA65 (100 08m) was applied to the main shoot apex of plants growing under short-day conditions, and all subsequently produced flowers opened. CCC, an inhibitor of gibberellin synthesis, was applied (0·06 per cent) to the soil of seedlings grown under long-day conditions. The CCC-treated plants were dwarfed and bore only closed flowers. With GA65 applied exogenously to the CCC-treated shoots, inhibition was released, resulting in elongated internodes and open flower production. The timing of flower production and internodal extension in Lamium amplexicaule are positively correlated. When floral primordia were removed from main shoots, the average internode lengths decreased. The number of nodes produced in treated plants was increased as a result of flower removal. Exogenous GA65 (10 08m) applied to the nodes from which flowers were removed resulted in internodal extension but had no effect on node number. Two processes that may contribute to the control of the production of open and closed flowers in Lamium amplexicaule are: (1) an increasing anther sac size from lower to upper node flowers that may exert control locally, via GN production, on corolla expansion, and (2) a photoperiodic control. |

| [17] | . |

| [18] | . |

| [19] | . Comparative ontogenetic study of the shoot apices and floral primordia of Viola odorata revealed significant differences between the dimorphic flowers in this cleistogamous (CL) species. Both the shoot apices and floral primordia of plants in the chasmogamous (CH) phase are larger than those in the CL phase. Form divergence occurs at petal initiation, and by the time of meiosis in the anthers, the CH flower is considerably larger in size. Mature CL flowers exhibit morphological modifications of the anterior petal spur, repressed growth of the staminal nectaries, and a recurving of the style which remains enclosed within the cone formed by five terminal anther caps. Pollination in the CL flower occurs as a result of pollen tubes penetrating the wall of an undehisced anther sac and growing to the stigmatic cavity nearby. |

| [20] | . |

| [21] | . Summary 1 Cleistogamy is a mating system found in approximately 300 species of flowering plants. Cleistogamous plants produce closed (cleistogamous, CL) flowers that require obligate self-pollination and open (chasmogamous, CH) flowers that allow for outcross-pollination. CL and CH flowers are induced by various environmental factors; this appears to be an adaptive mating strategy in unpredictable environments. 2 We examined the molecular basis of CL and CH flowering in Cardamine kokaiensis , which is closely related to the model flowering plant Arabidopsis thaliana . CL and CH flowering should be regulated by gene expression that is dependent on environmental conditions. By elucidating the molecular basis of CL and CH flowering, we can determine the changes in gene regulatory networks involved in the transition from CH to CL flowering. Furthermore, these results may help clarify the molecular evolutionary mechanisms leading to cleistogamy. 3 We regulated CL and CH flowering of C. kokaiensis using chilling treatments in a growth chamber. In a control treatment without chilling, C. kokaiensis produced CH and intermediate (INT) flowers. Long chilling of seedlings led to INT flowers, while long chilling of seeds induced the formation of CL flowers. Chilling seeds, and to a lesser extent of seedlings, induced early flowering and small plant size at flowering. 4 We also conducted a cross-species microarray analysis to compare gene expression patterns between CL and CH flowers using genomic DNA-based probe-selection strategy in an A. thaliana microarray. In this result, 69 genes, including genes related to floral development, auxin, flowering time, cold-stress, and drought-stress, were differentially expressed between CL and CH flowers. 5 Synthesis . This is the first report on the molecular basis of cleistogamy. We hypothesize that the interaction between the genetic network of the chilling response and that of floral development has been important in the evolution of cleistogamy in C. kokaiensis . Our results help to clarify the molecular basis for the evolution of plant mating systems that depend on environmental conditions. |

| [22] | . Dimorphic cleistogamy is a specialized form of mixed mating system where a single plant produces both open, potentially outcrossed chasmogamous (CH) and closed, obligately self-pollinated cleistogamous (CL) flowers. Typically, CH flowers and seeds are bigger and energetically more costly than those of CL. Although the effects of inbreeding and floral dimorphism are critical to understanding the evolution and maintenance of cleistogamy, these effects have been repeatedly confounded. In an attempt to separate these effects, we compared the performance of progeny derived from the two floral morphs while controlling for the source of pollen. That is, flower type and pollen source effects were assessed by comparing the performance of progeny derived from selfed CH vs. CL and outcrossed CH vs. selfed CH flowers, respectively. The experiment was carried out with the herb Ruellia nudiflora under two contrasting light environments. Outcrossed progeny generally performed better than selfed progeny. However, inbreeding depression ranges from low (1%) to moderate (36%), with the greatest value detected under shaded conditions when cumulative fitness was used. Although flower type generally had less of an effect on progeny performance than pollen source did, the progeny derived from selfed CH flowers largely outperformed the progeny from CL flowers, but only under shaded conditions and when cumulative fitness was taken into account. On the other hand, the source of pollen and flower type influenced seed predation, with selfed CH progeny the most heavily attacked by predators. Therefore, the effects of pollen source and flower type are environment-dependant and seed predators may increase the genetic differences between progeny derived from CH and CL flowers. Inbreeding depression alone cannot account for the maintenance of a mixed mating system in R. nudiflora and other unidentified mechanisms must thus be involved. |

| [23] | . Impatiens capensis displays a mixed mating system in which individual out-crossing rate is expected to increase with light and resource availability. We investigated the amount and spatial distribution of polygenic variation for 15 morphological traits within and among six natural populations of I. capensis growing in three distinct light habitats (shaded, mixed, full sun). We grew individuals from each population in uniform greenhouse conditions and detected significant genetic variation among families within populations for all the quantitative traits examined. However, only the features related to the vegetative characteristics of seedlings and sexually mature plants show also differentiation at the population level. Surprisingly, even though light availability is likely to be the most important factor affecting the mating system of I. capensis , we find that: (1) trait means of individuals from similar light environments are not more similar than those from different light environments; (2) partitioning of polygenic variance within and among families differs both among populations from the same light habitat and among characters within each population. If natural selection is maintaining such variation, it must operate primarily through heterogeneous selection pressure within, rather than between, populations. |

| [24] | . The reproductive biology of Impatiens pallida Nuttal and Impatiens biflora Walt (Balsaminaceae) was studied in relation to the evolutionary significance of cleistogamy and chasmogamy. Plant survivorship varied markedly between sites and was affected by abiotic agents such as drought and flooding, and occasional heavy damage from host-specific herbivores. Cleistogamy was the dominant mode of reproduction at all sites, but absolute and relative chasmogam production generally increased with total bud output. Extreme variability in seed production and reproductive mode was observed within and between sites. Cleistogams produced fewer seeds per ovary, matured faster and had a greater probability of surviving to produce seeds than chasmogams in all populations. The energetic investment in fertilization costs (i.e., sepals, petals, pollen and nectar) of chasmogams was >100 times that of cleistogams. Calculation of energetic expenditure per seed based on survivorship curves for each flower type and energy investment for major developmental stages indicated chasmogams were 2-3 times as costly as cleistogams. Greater chasmogam cost was also suggested by the earlier onset of senescence in greenhouse plants with high relative chasmogam output. Plants grown in the greenhouse under different light regimes displayed extreme plasticity in reproductive response as measured by absolute and relative output of cleistogams and chasmogams. The proportion of chasmogams produced per plant generally increased with light intensity. Plants collected from I. pallida populations where chasmogamy was rarely observed had significant chasmogam production when grown in the greenhouse. The tremendous differences observed in plant survivorship and reproductive output demonstrate a high degree of temporal and spatial variation in quality of Impatiens habitats. It is suggested that these conditions have exerted strong selective pressure for reproductive plasticity. Multipurpose genotypes capable of producing cleistogams and chasmogams, depending on habitat suitability, are highly adaptive in environments where genetic tracking is inefficient. The evolution of a dual reproductive mode in Impatiens provides seed production at minimal expense via cleistogamy and the opportunity for outcrossing and pollen donation through chasmogamy. The outcrossing potential of Impatiens chasmogams is enhanced by (1) functional monoecy and (2) a fivefold difference in relative lifespans (@M phase > @V), which results in strongly skewed intraplant sex ratios. |

| [25] | . Abstract Models for the evolution of a mixture of cleistogamous (closed, autogamous) flowers and chasmogamous (open) flowers are described. The ‘basic’ model takes into account features associated with cleistogamous self-pollination, including the greater economy and certainty of cleistogamous fertilization and the inability of cleistogamous flowers to contribute pollen to the outcrossed pollen pool. Complete cleistogamous selfing is favoured when allocation to maternal function, fertilization rate, and viability of progeny are sufficiently greater for the cleistogamous component, and when the resources spent on ancillary structures in cleistogamous flowers, cleistogamous seed costs, and inbreeding depression are low. The result is discussed with respect to the cost of sex argument and relevant ecological data. Suggestions for the apparent rarity of cleistogamy are presented. The ‘complex habitat’ model extends the basic model to situations in which the success of reproduction by cleistogamy or chasmogamy varies according to the environment of the parent. In this situation, reproduction by both cleistogamy and chasomogamy is sometimes selected. A ‘near and far dispersal’ model addresses the question of the evolution of dual modes of dispersal, which occur in some cleistogamous and non-cleistogamous plants. A dual mode of dispersal may evolve if a narrowly dispersed seed type is more successful in establishing at the sites located within its dispersal range compared with a second, more widely dispersed seed type which experiences less sib competition. The prediction is discussed with respect to data from amphicarpic plants. |

| [26] | . |

| [27] | . An optimality model based on the tradeoffs between seed set efficiency and outbreeding is presented that predicts under what conditions selfing should be favored over outcrossing. The model predicts that local density and distributional pattern, degree of environmental predictability, and adult and seed longevity are the independent variables that determine the shape of the marginal benefit curves for seed set and offspring heterogeneity. Some data supporting the model are presented derived from a study of species of the genus Leavenworthia (Cruciferae). |

| [28] | . Four lines of argument in favour of the suggestion that self fertilization is a favourable condition are discussed in detail: (1) in those genera in which species relationships have been studied from a phylogenetic point of view the self-fertilizing species are in general more specialized morphologically than their cross-fertilizing relatives; (2) many self-fertilizing species possess structure... |

| [29] | . . |

| [30] | . |

| [31] | . Abstract090000 The Violaceae consist of 1,0000900061,100 species of herbs, shrubs, lianas, and trees that are placed in 22 recognized genera. In this study we tested the monophyly of genera with a particular focus on the morphologically heterogeneous Rinorea and Hybanthus, the second and third most species-rich genera in the family, respectively. We also investigated intrafamilial relationships in the Violaceae with taxon sampling which included all described genera and several unnamed generic segregates. Phylogenetic inference was based on maximum parsimony, maximum likelihood, and Bayesian analyses of DNA sequences from the trnL/trnL090006F and rbcL plastid regions for 102 ingroup accessions. Results from phylogenetic analyses showed Rinorea and Hybanthus to be polyphyletic, with each genus represented by three and nine clades, respectively. Results also showed that most intrafamilial taxa from previous classifications of the Violaceae were not supported. The phylogenetic inferences presented in this study illustrate the need to describe new generic segregates and to reinstate other genera, as well as to revise the traditionally accepted intrafamilial classification, which is artificial and principally based on the continuous and homoplasious character state of floral symmetry. |

| [32] | . By using a generally applicable technique that involves monitoring the development and survivorship of flowers and seed capsules, I estimated the material and energetic costs of producing self- and cross-fertilized seeds in Impatiens capensis. All flowers and fruits on six plants were censused intensively for the two-month period of reproduction. Cleistogamous (selfing) flowers ripened seed in about 24 days, compared to about 36 days for the chasmogamous (outcrossing) flowers. In terms of dry weight, selfed seeds cost about two-thirds as much as outcrossed seeds: 12.4 versus 18.4 mg dry weight per seed. When adjusted to the currency of calories, and including an independent estimate of pollen and nectar production in outcrossing flowers, I estimate the costs to be about 65 and 135 calories per selfed or outcrossed seed. Sources of error include the accuracy of the estimates of flower and fruit weight, and possible differences among the developmental stages in respiratory costs. The cost discrepancy implies that outcrossed seeds should possess a countervailing fitness advantage large enough to offset their greater energetic cost. |

| [33] | . Seedlings derived from chasmogamous flowers of Impatiens capensis were competitively superior to those from cleistogamous (CL) flowers at several densities in the greenhouse. Chasmogamous seedlings had slightly better germination and survivorship than CL seedlings, and their final dry weight averaged 10% to 100% greater among four source populations. This difference did not vary consistently across densities. Initial size and maternal parent had important effects on performance at high density, but these were reduced when growth continued longer as at low density. The distributions of final weight ranged from near normal at low density to positively skewed and leptokurtic at high density, with a uniform coefficient of variation of about 60%. Chasmogamously produced seedlings were somewhat more variable than CL seedlings in final weight, but not on a log scale, so it is difficult to say how much their superiority depends on their variability. Although these differences were substantial, a moderate increase in the environmental variance could have obscured them. Variation exists between families and populations in the degree of fitness differential, suggesting differences in local genetic structure and/or the quality of pollination service. The smallest difference occurred in a highly inbred, isolated population, as expected if such conditions erode genetic variation. The superiority of the outcrossed seedlings in the outcrossing populations approaches their higher relative cost (Schemske, 1978; Waller, 1979), providing evidence for a short-term evolutionary equilibrium between these two modes of reproduction within at least some populations. |

| [34] | . ABSTRACT WANG, Y. (975 North Warson Road, Saint Louis, MO 63132), H. E. BALLARD, JR. (315 Porter Hall, Environmental and Plant Biology Department, Ohio University, Athens, OH 45701), R. R. MCNALLY (Department of Plant Pathology, Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI 48824), AND S. E. WYATT (315 Porter Hall, Environmental and Plant Biology Department, Ohio University, Athens, OH 45701). Gibberellins are involved but not sufficient to trigger a shift between chasmogamous-cleistogamous flower types in Viola pubescens. J. Torrey. Bot. Soc. 140: 1-8. 2013.-At least 50 angiosperm families have plants that produce both chasmogamous flowers and cleistogamous flowers. Various environmental and physiological factors, including the plant growth regulators gibberellins (GAs), have been reported to influence the flower types. Here, the relationship between GAs and flower production was studied for the first time in Viola, a genus famous for the large number of species with the mixed breeding system. Orthologs of genes for GA20 oxidase (VGA20ox) and GA3 oxidase (VGA3ox) were identified by reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) from a widespread North American species, Viola pubescens. Semi-quantitative RT-PCR indicated that both genes had increased expression in chasmogamous flowers as compared to cleistogamous flowers, supporting a role for GA in the differential production of flower type. However, the application of exogenous GA3 (the most common commercially available GA) to V. pubescens failed to induce a conversion of production of cleistogamous flowers to chasmogamous ones. Thus, increased levels of GAs in the floral buds appeared be related to flower type in the chasmogamous-cleistogamous mixed breeding system in V. pubescens, but exogenous application was not sufficient to induce an alteration in the type of flower produced. |

| [35] | . . 紫花地丁(Viola philippica)为典型的两型花自花受精植物,具有开放花和闭锁花混合繁育系统.通过对开放花和闭锁花花芽形态发育的比较发现:开放花与闭锁花在花芽发育早期形态相似,4轮花器官原基均正常发生.出现明显差异的时期为4轮花器官原基形成以后,小孢子发育时期为产孢细胞阶段,开放花的5个花瓣与5枚雄蕊继续发育,每个雄蕊有4个花药室;而闭锁花只有2枚雄蕊继续发育,每个雄蕊有2个花药室,其余雄蕊与所有的花瓣依然为器官原基状态,不再发育.通过对花芽与叶片可溶性糖与淀粉含量的检测发现,花器官原基形成之后,开放花与闭锁花形态出现明显差异阶段开始,随着花芽的发育,可溶性糖与淀粉含量均呈上升趋势,且开放花花芽中的含量均明显高于对应发育阶段闭锁花花芽;而开放花植株的叶片可溶性糖与淀粉含量均低于闭锁花植株叶片,说明开放花所需要的能量高于闭锁花,推测可溶性糖与淀粉含量的差异与两型花发育有一定的关系. |

1

1995

... 在紫花地丁中, 我们发现完全闭锁花与过渡闭锁花中, 雄蕊与花瓣的发育程度有一定的位置效应, 比如花芽腹侧的雄蕊发育最好, 而背面与侧部的雄蕊发育较弱, 最容易发育为膜质状或原基状结构.Li等(2016)的研究表明, 紫花地丁两型花的形态在花芽发育早期阶段即花器官发生阶段是相似的, 出现差异的时期是在花器官发生以后, 且小孢子发育为产孢细胞后的阶段(

Demographic and random amplified polymorphic DNA analyses reveal high levels of genetic diversity in a clonal violet

1

2001

... 两型的闭花受精植物由于闭锁花的完全自交以及开放花的部分自交, 可能会降低居群内或居群间的基因流, 导致自交衰退, 使居群的遗传多样性变低(

Plant dispersion, pollination and gene flow in

2

1976

... 两型的闭花受精植物由于闭锁花的完全自交以及开放花的部分自交, 可能会降低居群内或居群间的基因流, 导致自交衰退, 使居群的遗传多样性变低(

... ;

Cleistogamy in

2

1982

... 两型的闭花受精植物由于闭锁花的完全自交以及开放花的部分自交, 可能会降低居群内或居群间的基因流, 导致自交衰退, 使居群的遗传多样性变低(

... ), 并在不利的环境下保护花的生殖器官(

Cleistogamy in grasses

1

1983

... 两型的闭花受精植物由于闭锁花的完全自交以及开放花的部分自交, 可能会降低居群内或居群间的基因流, 导致自交衰退, 使居群的遗传多样性变低(

The cleistogamous breeding system: A review of its frequency, evolution, and ecology in angiosperms

2

2007

... 堇菜属(Viola)广泛分布在北温带及热带地区的山地森林中(

... ;

Population genetic structure of the cleistogamous plant speciesViola pubescens Aiton (Violaceae), as indicated by allozyme and ISSR molecular markers

1

2001

... 两型的闭花受精植物由于闭锁花的完全自交以及开放花的部分自交, 可能会降低居群内或居群间的基因流, 导致自交衰退, 使居群的遗传多样性变低(

Comparison of MADS box gene expression in developing male and female flowers of the dioecious plant white campion

1

1994

... 在紫花地丁中, 我们发现完全闭锁花与过渡闭锁花中, 雄蕊与花瓣的发育程度有一定的位置效应, 比如花芽腹侧的雄蕊发育最好, 而背面与侧部的雄蕊发育较弱, 最容易发育为膜质状或原基状结构.Li等(2016)的研究表明, 紫花地丁两型花的形态在花芽发育早期阶段即花器官发生阶段是相似的, 出现差异的时期是在花器官发生以后, 且小孢子发育为产孢细胞后的阶段(

Sex determination in the monoecious species cucumber is confined to specific floral whorls

1

2001

... 在紫花地丁中, 我们发现完全闭锁花与过渡闭锁花中, 雄蕊与花瓣的发育程度有一定的位置效应, 比如花芽腹侧的雄蕊发育最好, 而背面与侧部的雄蕊发育较弱, 最容易发育为膜质状或原基状结构.Li等(2016)的研究表明, 紫花地丁两型花的形态在花芽发育早期阶段即花器官发生阶段是相似的, 出现差异的时期是在花器官发生以后, 且小孢子发育为产孢细胞后的阶段(

Stamen-derived bioactive gibberellin is essential for male flower development of Cucurbita maxima L

1

2012

... 笋瓜(Cucurbita maxima)和黄瓜(Cucumis sativus)雌/雄花的雄蕊与雌蕊中均存在赤霉素(GA)含量的不均匀分布, 进而影响雄花或雌花的发育(

Ovary-derived precursor gibberellin A9 is essential for female flower development in cucumber

1

2016

... 笋瓜(Cucurbita maxima)和黄瓜(Cucumis sativus)雌/雄花的雄蕊与雌蕊中均存在赤霉素(GA)含量的不均匀分布, 进而影响雄花或雌花的发育(

Chasmogamous and cleistogamous pollination inSalpiglossis sinuata

1

1978

... 笋瓜(Cucurbita maxima)和黄瓜(Cucumis sativus)雌/雄花的雄蕊与雌蕊中均存在赤霉素(GA)含量的不均匀分布, 进而影响雄花或雌花的发育(

Expression of B-class MADS-box genes in response to variations in photoperiod is associated with chasmogamous and cleistogamous flower development inViola philippica

6

2016

... 堇菜属(Viola)广泛分布在北温带及热带地区的山地森林中(

... ;

... 紫花地丁(Viola philippica)为堇菜属多年生草本植物, 是一种典型的具有开放花与闭锁花的两型闭花授精植物.光周期是影响紫花地丁两型花形成的主要生态因子, 短日照下发育的花主要为开放花, 长日照(光周期大于14 h)下形成完全闭锁花(

... ).但该物种的开放花与完全闭锁花之间还存在着一种过渡闭锁花(intermediate cleistogamous), 其中, 在短日照下有少数花芽为过渡闭锁花, 中日照下大部分花芽为过渡闭锁花(

... 本次数据与前期研究结果(

...

Cloning and characterization of paleoAP3-like MADS-box gene in London plane tree

1

2012

... 在紫花地丁中, 我们发现完全闭锁花与过渡闭锁花中, 雄蕊与花瓣的发育程度有一定的位置效应, 比如花芽腹侧的雄蕊发育最好, 而背面与侧部的雄蕊发育较弱, 最容易发育为膜质状或原基状结构.Li等(2016)的研究表明, 紫花地丁两型花的形态在花芽发育早期阶段即花器官发生阶段是相似的, 出现差异的时期是在花器官发生以后, 且小孢子发育为产孢细胞后的阶段(

紫花地丁开放花和闭锁花繁殖特征的研究

1

2006

... 紫花地丁(Viola philippica)为堇菜属多年生草本植物, 是一种典型的具有开放花与闭锁花的两型闭花授精植物.光周期是影响紫花地丁两型花形成的主要生态因子, 短日照下发育的花主要为开放花, 长日照(光周期大于14 h)下形成完全闭锁花(

Physiological controlson the production of cleistogamous and chasmogamous flowers in Lamium amplexicaule L.(Labiatae)

1

1979

... 笋瓜(Cucurbita maxima)和黄瓜(Cucumis sativus)雌/雄花的雄蕊与雌蕊中均存在赤霉素(GA)含量的不均匀分布, 进而影响雄花或雌花的发育(

Cleistogamy: A tool for the study of floral morphogenesis function and evolution

1

1981

... 堇菜属(Viola)广泛分布在北温带及热带地区的山地森林中(

Cleistogamy and phylogenetic position ofViola uliginosa(Violaceae) re-examined

2

2016

... 堇菜属(Viola)广泛分布在北温带及热带地区的山地森林中(

...

Comparative flower development in the cleistogamous speciesViola odorata. I. A growth rate study

1

1983

... 堇菜属(Viola)广泛分布在北温带及热带地区的山地森林中(

Effects of water stress, abscisicacid, and gibberellic acid on flower production and differentiation in the cleistogamous speciesCollomia grandiflora Dougl. ex Lindl.(Polemoniaceae)

1983

Ecogenomics of cleistogamous and chasmogamous flowering: Genome- wide gene expression patterns from cross-species microarrayanalysis inCardamine kokaiensis(Brassicaceae)

1

2008

... 开花是被子植物有性繁殖过程中的一个关键阶段, 但不是所有的花都能开放来展示其内部结构, 有些植物的花始终不开放, 通过自花受精产生种子,这种花被称为闭锁花(cleistogamous).而一些产生闭锁花的植物也能产生开放花(chasmogamous), 能通过远交产生种子.如在禾本科、远志科、凤仙花科、豆科和堇菜科等亲缘关系比较远的开花植物类群中都有闭锁花现象.早在1908年科学家们就描述了30多种植物的开放花与闭锁花形态, 并认为花瓣与雄蕊数量的减少是闭锁花最普遍的特征(

The effect of pollen source vs. flower type on progeny performance and seed predation under contrasting light environments in a cleistogamous herb

1

2013

... 两型的闭花受精植物由于闭锁花的完全自交以及开放花的部分自交, 可能会降低居群内或居群间的基因流, 导致自交衰退, 使居群的遗传多样性变低(

Spatial patterns of polygenic variation in Impatiens capensis, a species with an environmentally controlled mixed mating system

1

1999

... 两型的闭花受精植物由于闭锁花的完全自交以及开放花的部分自交, 可能会降低居群内或居群间的基因流, 导致自交衰退, 使居群的遗传多样性变低(

Evolution of reproductive characteristics inImpatiens(Balsaminaceae): The significance of cleistogamy and chasmogamy

3

1978

... 两型的闭花受精植物由于闭锁花的完全自交以及开放花的部分自交, 可能会降低居群内或居群间的基因流, 导致自交衰退, 使居群的遗传多样性变低(

... ); 而闭锁花绝对的自交能在远交不利的情况下为植物提供繁殖保障(

... ;

The selection of cleistogamy and heteromorphic diaspores

1

1984

... 两型的闭花受精植物由于闭锁花的完全自交以及开放花的部分自交, 可能会降低居群内或居群间的基因流, 导致自交衰退, 使居群的遗传多样性变低(

Ruellia brevifolia (Pohl) Ezcurra (Acanthaceae): Flowering phenology, pollination biology and reproduction

1

2002

... 开花是被子植物有性繁殖过程中的一个关键阶段, 但不是所有的花都能开放来展示其内部结构, 有些植物的花始终不开放, 通过自花受精产生种子,这种花被称为闭锁花(cleistogamous).而一些产生闭锁花的植物也能产生开放花(chasmogamous), 能通过远交产生种子.如在禾本科、远志科、凤仙花科、豆科和堇菜科等亲缘关系比较远的开花植物类群中都有闭锁花现象.早在1908年科学家们就描述了30多种植物的开放花与闭锁花形态, 并认为花瓣与雄蕊数量的减少是闭锁花最普遍的特征(

On the relative advantages of cross- and self-fertilization

3

1976

... 两型的闭花受精植物由于闭锁花的完全自交以及开放花的部分自交, 可能会降低居群内或居群间的基因流, 导致自交衰退, 使居群的遗传多样性变低(

... ;

... ), 减少因吸引传粉者所需的能量投入(

Self fertilization and population variability in the higher plants

2

1957

... 两型的闭花受精植物由于闭锁花的完全自交以及开放花的部分自交, 可能会降低居群内或居群间的基因流, 导致自交衰退, 使居群的遗传多样性变低(

... ), 保存有利的基因型(

爱氏苏木精整体染色及番红-固绿双重染色滴染法在石蜡切片中的运用

1

1984

... 采用爱氏苏木精整体染色法(

Cleistogamic flowers

1

1938

... 开花是被子植物有性繁殖过程中的一个关键阶段, 但不是所有的花都能开放来展示其内部结构, 有些植物的花始终不开放, 通过自花受精产生种子,这种花被称为闭锁花(cleistogamous).而一些产生闭锁花的植物也能产生开放花(chasmogamous), 能通过远交产生种子.如在禾本科、远志科、凤仙花科、豆科和堇菜科等亲缘关系比较远的开花植物类群中都有闭锁花现象.早在1908年科学家们就描述了30多种植物的开放花与闭锁花形态, 并认为花瓣与雄蕊数量的减少是闭锁花最普遍的特征(

A phylogeny of the Violaceae (Malpighiales) inferred from plastid DNA sequences: Implications for generic diversity and intrafamilial classification

1

2014

... 堇菜属(Viola)广泛分布在北温带及热带地区的山地森林中(

The relative costs of self- and cross-fertilized seeds in Impatiens capensis(Balsaminaceae)

1

1979

... 两型的闭花受精植物由于闭锁花的完全自交以及开放花的部分自交, 可能会降低居群内或居群间的基因流, 导致自交衰退, 使居群的遗传多样性变低(

Differences in fitness between seedlings derived from cleistogamous and chasmogamous flowers inImpatiens capensis

1

1984

... 两型的闭花受精植物由于闭锁花的完全自交以及开放花的部分自交, 可能会降低居群内或居群间的基因流, 导致自交衰退, 使居群的遗传多样性变低(

Gibberellins are involved but not sufficient to trigger a shift between chasmogamous-cleistogamous flower types inViola pubescens

2

2013

... 开花是被子植物有性繁殖过程中的一个关键阶段, 但不是所有的花都能开放来展示其内部结构, 有些植物的花始终不开放, 通过自花受精产生种子,这种花被称为闭锁花(cleistogamous).而一些产生闭锁花的植物也能产生开放花(chasmogamous), 能通过远交产生种子.如在禾本科、远志科、凤仙花科、豆科和堇菜科等亲缘关系比较远的开花植物类群中都有闭锁花现象.早在1908年科学家们就描述了30多种植物的开放花与闭锁花形态, 并认为花瓣与雄蕊数量的减少是闭锁花最普遍的特征(

... 堇菜属(Viola)广泛分布在北温带及热带地区的山地森林中(

紫花地丁开放花与闭锁花的发育及可溶性糖与淀粉含量的研究

2

2017

... 紫花地丁(Viola philippica)为堇菜属多年生草本植物, 是一种典型的具有开放花与闭锁花的两型闭花授精植物.光周期是影响紫花地丁两型花形成的主要生态因子, 短日照下发育的花主要为开放花, 长日照(光周期大于14 h)下形成完全闭锁花(

... 在紫花地丁中, 我们发现完全闭锁花与过渡闭锁花中, 雄蕊与花瓣的发育程度有一定的位置效应, 比如花芽腹侧的雄蕊发育最好, 而背面与侧部的雄蕊发育较弱, 最容易发育为膜质状或原基状结构.Li等(2016)的研究表明, 紫花地丁两型花的形态在花芽发育早期阶段即花器官发生阶段是相似的, 出现差异的时期是在花器官发生以后, 且小孢子发育为产孢细胞后的阶段(