邓益琴1, 徐力文1, 张亚秋1,2, 郭志勋1, 冯娟1

1. 中国水产科学研究院南海水产研究所, 农业农村部南海渔业资源开发利用重点实验室, 广东 广州 510300;

2. 上海海洋大学水产与生命学院, 上海 201306

收稿日期:2020-03-09;修回日期:2020-05-10;网络出版日期:2020-10-10

基金项目:国家自然科学基金(31902415);广东省自然科学基金(2018A030310695,2019A1515011833);中国水产科学研究院南海水产研究所中央级公益性科研院所基本科研业务费专项(2019TS04);中国水产科学研究院基本科研业务费(2019ZD0707)

*通信作者:冯娟, Tel/Fax:+86-20-8910832;E-mail:jannyfeng@163.com.

摘要:[目的] 为探讨我国华南沿海海水养殖鱼类病原菌美人鱼发光杆菌的非典型毒力基因和耐药性的时空变化,解析影响其毒力和耐药性变化的可能环境因素,为该菌所引起的病害防控提供建议。[方法] 本研究以分离自我国广东和海南沿海患病海水鱼的35株美人鱼发光杆菌为研究对象,利用普通PCR扩增技术,分析5个非典型毒力基因在菌株中的分布情况,并采用纸片扩散法(K-B)分析菌株对15种抗生素的耐药性。[结果] 19株菌含有1–2个被检测的非典型毒力基因,尤其是hlyA和vvh的检出率均高于20%。35株菌多重耐药指数为0.00–0.67,表现出27种耐药谱,多重耐药率(菌株耐抗生素种类>3)达到60.00%,尤其对万古霉素、阿莫西林、麦迪霉素和利福平的耐药率均高于50%,但对庆大霉素、诺氟沙星、环丙沙星、氯霉素和氟苯尼考的耐药率均低于10%。非典型毒力基因含量和耐药性,呈现一定的随年份增加而增强以及海南>广东的时空差异,尤其是耐药性中的谱型丰富度、多重耐药率、某一菌株的最多耐药数量以及多重耐药指数,海南(分别是1.00,69.23%,10,0.32)均大于广东(分别是0.82,54.55%,9,0.25)。[结论] 美人鱼发光菌的非典型毒力基因可能是通过水平基因转移获得,海南与广东区域美人鱼发光菌毒力基因与耐药的差异主要受到温度和抗生素使用的影响。

关键词:美人鱼发光杆菌非典型毒力基因耐药性时空差异

Analysis of virulence genes and antibiotic resistance of Photobacterium damselae isolated from marine fishes in coastal South China

Yiqin Deng1, Liwen Xu1, Yaqiu Zhang1,2, Zhixun Guo1, Juan Feng1

1. Key Laboratory of South China Sea Fishery Resources Exploitation&Utilization, Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs, South China Sea Fisheries Research Institute, Chinese Academy of Fishery Sciences, Guangzhou 510300, Guangdong Province, China;

2. College of Fisheries and Life Science, Shanghai Ocean University, Shanghai 201306, China

Received: 9 March 2020; Revised: 10 May 2020; Published online: 10 October 2020

*Corresponding author: Juan Feng, Tel/Fax: +86-20-8910832; E-mail: jannyfeng@163.com.

Foundation item: Supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31902415), by the Natural Science Fund of Guangdong Province (2018A030310695, 2019A1515011833), by the Central Public-interest Scientific Institution Basal Research Fund, South China Sea Fisheries Research Institute, CAFS (2019TS04) and by the Central Public-interest Scientific Institution Basal Research Fund (CAFS) (2019ZD0707)

Abstract: [Objective] The aim of this research is to study the temporal and spatial changes of atypical virulence genes and drug resistance of the marine fish pathogen Photobacterium damselae in South China, and analyze the potential environmental factors driving the change of virulence and drug resistance in P. damselae, and consequently provide suggestions for disease prevention and control caused by P. damselae. [Methods] Based on PCR and Kirby-Bauer diffusion method, we analyzed the presence of 5 atypical virulence genes and the resistance to 15 tested antibiotics of 35 P. damselae strains isolated from diseased marine fishes in South China coastal area. [Results] The results show that:(1) 19 strains contained 1-2 atypical virulence genes, particularly, the detection rate of hlyA and vvh were higher than 20%; (2) 27 resistance types were observed in these 35 strains, the multi-antibiotic resistance index of was 0.00-0.67 with the multi-antibiotic resistance rate (one strain shows resistance to more than 3 antibiotics) up to 60.00%. Therein, more than 50% strains showed resistance to vancomycin, amoxicillin, midecamycin and rifampin, but less than 10% strains resisted to gentamicin, norfloxacin, ciprofloxacin, chloramphenicol and florfenicol; (3) The atypical virulence gene contents and drug resistance were marginally increased with the year grows, and more/stronger in Hainan than in Guangdong. Further, the richness of resistance types, multi-antibiotic resistance rate, the most resistant number in one strain, and multi-antibiotic resistance index were observed higher/more in Hainan (1.00, 69.23%, 10, 0.32, respectively) than in Guangdong (0.82, 54.55%, 9, 0.25, respectively). [Conclusion] These results indicated that atypical virulence genes probably be transferred into P. damselae by horizontal gene transfer and the variation of virulence and drug resistance of P. damselae isolated form Hainan and Guangdong are mainly affected by temperature and antibiotic pollution.

Keywords: Photobacterium damselaeatypical virulence geneantibiotic resistancetemporal and spatial differences

美人鱼发光杆菌(Photobacterium damselae)又称嗜盐海弧菌,是革兰氏阴性球杆菌,包括美人鱼亚种(Photobacterium damselae subsp.damselae;PDD)和杀鱼亚种(Photobacterium damselae subsp. psicicida;PDP) 2个亚种。其中,美人鱼亚种被认为是一种广泛病原菌,可感染各种鱼类、甲壳类和软体类等海洋动物,并引起出血、败血症和皮肤溃疡等,甚至引起人的坏死性筋膜炎、蜂窝织炎和脓肿等[1],其被认为是2015年中国东部养殖银鲳疾病大暴发的病原[2]。杀鱼亚种则是一种相对专一病原菌,仅感染鱼类,导致巴氏杆菌病(Pasteurellosis)[1]。巴氏杆菌病也因其宿主范围广、死亡率高、分布广而被认为是世界范围内海水养殖中最具威胁性的细菌性疾病之一[3]。该病在包括黄尾鱼、金枪鱼、鲈鱼、比目鱼、军曹鱼和金鲳鱼在内的各种海洋鱼类中被发现和报道,对日本、欧洲、美国、台湾和中国内地等各个国家和地区的海水养殖业造成严重经济损失[4-5]。该病被报道引起中国秦皇岛市昌黎县某海水养殖基地25%的舌鳎突然死亡[6],引起欧洲60%–80%的养殖海鲈死亡[5]。

美人鱼发光杆菌具有重要的致病因子,如胞外蛋白酶类、胞外溶血素和细胞毒素等,导致其感染甚至致死宿主[7]。美人鱼发光杆菌基因组被发现具有高度可塑性,其大量的毒力和耐药基因通过质粒等编码,并可通过水平基因转移获得毒力和耐药基因等,从而增强其致病性和耐药性等[8-9]。如美人鱼亚种通过毒力岛水平传播获得弧菌铁载体蛋白基因pvsD[9]。杀鱼亚种通过pPHDP70质粒水平传播铁载体蛋白、外膜受体、ABC转运体以及转录调控因子等,甚至可以将这些基因水平转移到霍乱弧菌、拟弧菌以及鳗弧菌等病原弧菌中[10]。由此可见,水平基因转移是增强美人鱼发光杆菌致病性和耐药性并促进其进化的重要途径。

目前,由于疫苗和免疫增强剂等其他控制方法的局限性,抗生素被认为是对抗细菌性传染病最有效、最灵活的武器,被广泛用于预防或治疗水产养殖中的细菌性疾病[11-12]。例如,土霉素被用于埃及和西班牙等国家沿海地区海鲷和海鲈养殖中美人鱼发光杆菌等病原的控制[13]。在挪威,氟苯尼考和恶唑酸主要用于控制鳕鱼鱼苗的弧菌病[14]。目前,针对水产养殖抗生素使用的监管措施非常有限,不同地区和国家之间监管措施以及执行力度差别迥异[15]。仅中国每年约有5.4万t抗生素被人和动物排泄到环境中[16]。抗生素的过度使用导致耐药和多重耐药细菌被选择和积累[17-18]。Chiu等[19]报道分离自台湾地区养殖的澳洲鲈鱼和军曹鱼的美人鱼发光杆菌对氯霉素、庆大霉素、阿莫西林和青霉素G耐药率均高于90%。此外,抗生素在食用组织中的积聚会导致过敏、毒性、肠道菌群紊乱和耐药性[11]。如食物中氯霉素的沉积将导致整形病,进而导致严重的骨髓疾病[11]。因此,细菌耐药性的调查有助于评估抗生素的滥用情况,并指导今后水产养殖中的病害防控。

中国海水鱼养殖业已发展了50多年,并且在华南沿海地区得到快速发展。2018年,中国华南沿海地区海水鱼养殖产量达到500万t,占中国总海水鱼养殖产量的1/4[20]。然而,高密度的养殖模式、剧烈的人类活动和全球气候变化等,导致近年来水产病害频发、暴发[21-22]。美人鱼发光杆菌的2个亚种,对鱼类、甲壳类、软体类甚至人类健康造成威胁[1]。鉴于此,本研究分析了分离自中国华南沿海海水养殖患病鱼的35株美人鱼发光杆菌中5个非典型毒力基因(不属于美人鱼发光杆菌特有的毒力基因,但属于其他病原菌特有的毒力基因)的存在情况,并检测了其对15种常见抗生素的敏感性,从而获悉其通过水平基因转移获得毒力基因的情况以及耐药谱型的多样性,基于此分析毒力基因和耐药性的时空变化。本研究将有助于评估美人鱼发光杆菌的致病潜力,揭示其毒力和耐药的影响因素,并指导海水鱼养殖病害的有效防控。

1 材料和方法 1.1 实验菌株来源 35株美人鱼发光杆菌为笔者实验室保藏菌株,于2011–2016年分离自广东和海南沿海养殖的患病鱼,其中广东沿岸(包括企水、乌石、饶平、惠东、深圳等)分离株22株,其宿主主要是青斑、金鲳、鞍带石斑鱼、红鱼、篮子鱼、鮸鱼等;海南沿岸(包括新村、烟堆、三亚、潭门、黎安等)分离株13株,其宿主主要是虎斑、珍珠龙胆、金鲳等(表 1)。

表 1. 菌株信息 Table 1. The information of strains

| No. | Strains | Hosts | Sites | Provinces | Years |

| 1 | P11WS30 | Epinephelus awoara | Wushi | Guangdong | 2011 |

| 2 | P11QS25B | Trachinotus ovatus | Qishui | Guangdong | 2011 |

| 3 | P11QS24 | Trachinotus ovatus | Qishui | Guangdong | 2011 |

| 4 | P11WS | Epinephelus awoara | Wushi | Guangdong | 2011 |

| 5 | P11WS31 | Epinephelus awoara | Wushi | Guangdong | 2011 |

| 6 | P12ZJ1202 | Epinephelus lanceolatus | Zhanjiang | Guangdong | 2012 |

| 7 | P12RP06 | Lutjanus erythropterus | Raoping | Guangdong | 2012 |

| 8 | P12RP03 | Lutjanus erythropterus | Raoping | Guangdong | 2012 |

| 9 | P13ZJ01 | Epinephelus awoara | Wushi | Guangdong | 2013 |

| 10 | P13HD04 | White snapper | Huidong | Guangdong | 2013 |

| 11 | P13HD02 | Siganus spp. | Huidong | Guangdong | 2013 |

| 12 | P13RP02 | Miichthys miiuy | Raoping | Guangdong | 2013 |

| 13 | P13XC01 | Trachinotus ovatus | Shenzhen | Guangdong | 2013 |

| 14 | P13HD03 | Siganus spp. | Huidong | Guangdong | 2013 |

| 15 | P13ZJ06 | Siganus spp. | Zhanjiang | Guangdong | 2013 |

| 16 | P14RP2701 | Miichthys miiuy | Raoping | Guangdong | 2014 |

| 17 | P14RP2102 | Miichthys miiuy | Raoping | Guangdong | 2014 |

| 18 | P14RP2201 | Miichthys miiuy | Raoping | Guangdong | 2014 |

| 19 | P14RP21 | Miichthys miiuy | Raoping | Guangdong | 2014 |

| 20 | P14SZ08 | Epinephelus fuscoguttatus (♀)×E. lanceolatus (♂) | Shenzhen | Guangdong | 2014 |

| 21 | P14RP34 | Miichthys miiuy | Raoping | Guangdong | 2014 |

| 22 | P16RP0102 | Miichthys miiuy | Raoping | Guangdong | 2016 |

| 23 | P12XC2501 | Blotchy rock cod | Li’an | Hainan | 2012 |

| 24 | P12YD18 | Blotchy rock cod | Tanmen | Hainan | 2012 |

| 25 | P12YD19 | Blotchy rock cod | Tanmen | Hainan | 2012 |

| 26 | P12PC15 | Epinephelus fuscoguttatus (♀)×E. lanceolatus (♂) | Xincun | Hainan | 2012 |

| 27 | P12XC21 | Epinephelus fuscoguttatus (♀)×E. lanceolatus (♂) | Xincun | Hainan | 2012 |

| 28 | P13YD18 | Epinephelus fuscoguttatus (♀)×E. lanceolatus (♂) | Yandui | Hainan | 2013 |

| 29 | P13YD12 | Epinephelus fuscoguttatus (♀)×E. lanceolatus (♂) | Yandui | Hainan | 2013 |

| 30 | P13YD10 | Epinephelus fuscoguttatus (♀)×E. lanceolatus (♂) | Yandui | Hainan | 2013 |

| 31 | P13XC24 | Blotchy rock cod | Xincun | Hainan | 2013 |

| 32 | P13SY07 | Trachinotus ovatus | Sanya | Hainan | 2013 |

| 33 | P13YD11 | Epinephelus fuscoguttatus (♀)×E. lanceolatus (♂) | Yandui | Hainan | 2013 |

| 34 | P13YD18 | Epinephelus fuscoguttatus (♀)×E. lanceolatus (♂) | Yandui | Hainan | 2013 |

| 35 | P16PC04 | Epinephelus fuscoguttatus (♀)×E. lanceolatus (♂) | Xincun | Hainan | 2016 |

表选项

1.2 细菌基因组DNA提取 冻存细菌划线于2216E平板,于28 ℃培养箱中倒置培养过夜。挑单克隆培养于2 mL 2216E液体培养基中,于28 ℃摇床中200 r/min振摇培养过夜。按照细菌基因组DNA提取试剂盒(天根,中国)提取基因组DNA。用Nanodrop-2000 (Thermo,USA)测定基因组DNA浓度,并用0.75%浓度的琼脂糖胶确定。

1.3 非典型毒力基因的PCR分析 普通PCR检测美人鱼发光杆菌中哈维弧菌溶血素基因vhh、霍乱弧菌溶血素基因hlyA、副溶血弧菌耐热直接溶血素(Thermostable direct haemolysin)基因tdh以及TDH相关溶血素基因trh和创伤弧菌溶血素基因vvh的存在情况。本研究所用引物序列见表 2。

表 2. 本研究所用的引物序列 Table 2. The primer sequences used in this study

| Primer names | Sequences (5′→3′) | References | Sizes/bp | Typical hosts |

| vhh-F | GATTGGGAATGGGCAGAAAA | This study | 319 | V. harveyi |

| vhh-R | GGAATCGCCATTGTGATGC | |||

| hlyA-F | GGCAAACAGCGAAACAAATACC | [23] | 738 | V. cholerae |

| hlyA-R | CTCAGCGGGCTAATACGGTTTA | |||

| tdh-F | CCACTACCACTCTCATATGC | [24] | 250 | V. parahaemolyticus |

| tdh-R | ATACGAGTGGTTGCTGTCATG | |||

| trh-F | CAGTTTGCTATTGGCTTCG | This study | 302 | V. parahaemolyticus |

| trh-R | CAGAAAGAGCAGCCATTG | |||

| vvh-F | GCTATTTCACCGCCGCTCAC | [25] | 222 | V. vulnificus |

表选项

20 μL PCR反应体系包括Taq预混液(TaKaRa Taq Version 2.0 plus dye) (TaKaRa,Japan) 10.0 μL,上下游引物(10 μmol/L)各1.0 μL,模板DNA (20 ng/L) 1.0 μL (以灭菌水为阴性对照,以各目标基因合成条带作为阳性对照),灭菌水7.0 μL。在PCR热循环仪(Bio-Rad,USA)中扩增目的基因,反应条件如下:95 ℃ 5 min;95 ℃ 30 s,Tm 30 s,72 ℃ 60 s/kb,35个循环;72 ℃ 10 min。PCR产物通过1.0%琼脂糖胶电泳检测。

根据多重耐药指数(Multi-antibiotic resistance indexes,MARIs)[26],此次我们定义多重毒力基因指数(Multi-virulence gene indexes,MVGIs)为某一细菌5种非典型毒力基因检出数量与5种非典型毒力基因检出数量5的比值。

1.4 耐药性分析 采用纸片扩散法(K-B)[27]进行实验,记录药敏纸片抑菌圈的直径。药敏纸片为15种常见抗生素(购自于杭州天河微生物试剂有限公司):包括呋喃唑酮(FUR,300 μg/片)、红霉素(ERY,150 μg/片)、庆大霉素(GEN,10 μg/片)、利福平(RIF,5 μg/片)、诺氟沙星(NOR,10 μg/片)、环丙沙星(CIP,50 μg/片)、氯霉素(CHL,30 μg/片)、氟苯尼考(FLO,30 μg/片)、四环素(TET,30 μg/片)、复方新诺明(T/S,23.75/1.25 μg/片)、阿莫西林(AMO,20 μg/片)、万古霉素(VAN,30 μg/片)、妥布霉素(TOB,10 μg/片),麦迪霉素(MID,30 μg/片)和多西环素(DOX,300 μg/片)。以大肠杆菌ATCC 35218为质控菌,进行各批次测试的质控,参照美国临床和实验室标准协会(Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute,CLSI)抗生素敏感试验标准对耐药谱进行分析[28]。

1.5 耐药谱的分析 根据抗生素所形成的抑菌圈直径大小,将每种抗生素的耐药情况用S (Sensitive)、I (Intermediate)、R (Resistant)记录,每株菌株对15种抗生素形成唯一的耐药谱。对耐药谱进行统计分类,计算耐药率、多重耐药指数和耐药谱型丰富度,并分析不同分离地区和分离时间菌株耐药谱型的差异。

耐药率(Antibiotic resistance rate,ARR):对某一抗生素的耐药菌株数与检测的总菌株数的比率;

多重耐药指数(Multi-antibiotic resistance indexes,MARIs):某一细菌对15种测试抗生素耐受的抗生素数目与15种测试抗生素总数目15的比值;

耐药谱型丰富度:菌株具有的耐药谱型数量与菌株数量的比值。

1.6 统计分析 采用SPSS 19.0[29]软件对广东和海南菌株的多重毒力基因指数和多重耐药指数进行student’s t检验,对2011–2014年间菌株的多重毒力基因指数和多重耐药指数进行单因素方差(One-way ANOVA)分析。P < 0.05被认为显著差异。

2 结果和分析 2.1 美人鱼发光杆菌非典型毒力基因的分布 5个非典型毒力基因在35株美人鱼发光杆菌中的检出率,由高到低依次为hlyA (20.00%)、vvh (20.00%)、trh (11.43%)、vhh (8.57%)和tdh (5.71%) (图 1-A)。其中,4株菌含有2个非典型毒力基因,15株菌含有1个非典型毒力基因,而其余16株菌不含所检测的5个非典型毒力基因(图 1-B)。

|

| 图 1 菌株非典型毒力基因的分布情况 Figure 1 The distribution of atypical virulence genes in strains. A: The detection rate of each atypical virulence gene; B: The strains with different number of atypical virulence genes. |

| 图选项 |

2.2 美人鱼发光杆菌非典型毒力基因的时空差异 t检验表明,广东和海南分离菌株的多重毒力基因指数差异不显著(F=0.226,P=0.638) (图 2-A)。hlyA、vvh、trh、vhh和tdh在广东分离的美人鱼发光杆菌中的检出率分别为18.18%、18.18%、13.64%、9.09%和9.09%,而在海南分离的美人鱼发光杆菌中的检出率分别为23.08%、23.08%、7.69、7.69%和0.00% (图 2-B)。因此,hlyA和vvh的检出率海南高于广东,而trh、vhh和tdh的检出率海南低于广东(图 2-B)。

|

| 图 2 各非典型毒力基因时空分布差异 Figure 2 The spatial and temporal difference of atypical virulence genes. A: Multi-virulence gene index of isolates from Guangdong and Hainan; B: The detection rate of each atypical virulence gene of isolates from Guangdong and Hainan; C: Multi-virulence gene index of isolates from 2011 to 2014; D: The detection rate of each atypical virulence gene of isolates from 2011 to 2014. |

| 图选项 |

单因素方差分析表明,各年份之间的多重毒力基因指数差异性不显著(F=0.193,P=0.901) (图 2-C),但整体上,hlyA和vvh的检出率随年份增加呈现一定的增加趋势,而trh、vhh和tdh的检出率随年份增加呈现一定的下降趋势(图 2-D)。

2.3 美人鱼发光杆菌的耐药性 35株美人鱼发光杆菌对15种抗生素的耐药情况差异较大(图 3-A),对万古霉素、阿莫西林、麦迪霉素和利福平表现出强耐药性(耐药 > 50%),耐药率分别为91.43%、68.57%、68.57%和62.86%;对红霉素表现出中等耐药(25%–50%),耐药率为34.29%;对妥布霉素、多西环素、四环素、呋喃唑酮和复方新诺明的耐药率低(10%–25%),依次为20.00%、17.14%、14.29%、11.43%和11.43%;对庆大霉素、诺氟沙星和环丙沙星耐药率低于10%,分别为8.57%、5.71%和5.71%;而对氯霉素和氟苯尼考完全敏感。

|

| 图 3 菌株耐药情况 Figure 3 The antibiotic resistance of isolates. A: The resistance rate of strains to each antibiotic; B: The strains resistant to different number of antibiotics. VAN: Vancomycin; AMO: Amoxicillin; MID: Midecamycin; RIF: Rifampicin; ERY: Erythromycin; TOB: Tobramycin; DOX: Doxycycline; FUR: Furazolidone; TET: Tetracycline; T/S: Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole; GEN: Gentamicin; NOR: Norfloxacin; CIP: Ciprofloxacin; CHL: Chloramphenicol; FLO: Florfenicol. |

| 图选项 |

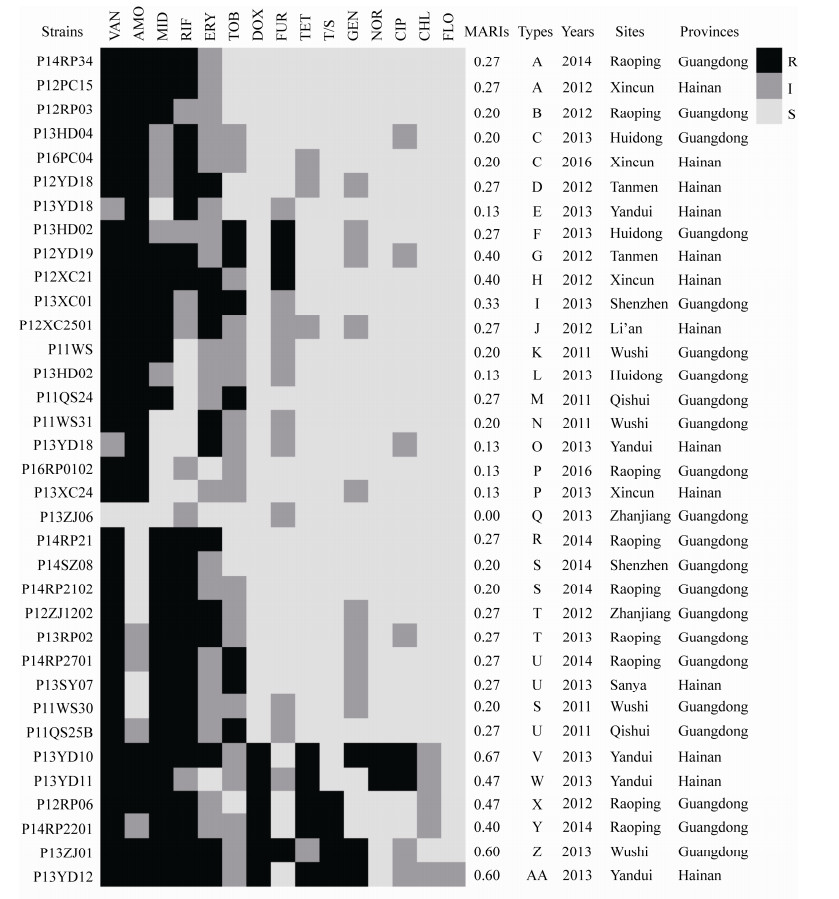

35株菌的多重耐药指数(MARIs)范围为0.00–0.67,表现出27种耐药谱(A–AA),耐药谱型丰富度为0.77。菌株P13ZJ06对所测试的15种抗生素均敏感;5株菌对所测定的2种抗生素耐受(耐药谱型为E,L,O,P);8株菌对所测定的3种抗生素耐受(耐药谱型为B,C,K,N,S);其他21株菌对所测定的3种以上抗生素耐受,多重耐药率(菌株耐抗生素种类 > 3)达到60.00%,多重耐药谱有17种,谱型丰富度为0.81;并且P13YD10对所测定的10种抗生素耐受,耐药性最强(图 3-B,图 4)。

|

| 图 4 各菌株耐药谱 Figure 4 The isolates resistance types. R: Resistance; I: Intermediate; S: Susceptible. VAN: Vancomycin; AMO: Amoxicillin; MID: Midecamycin; RIF: Rifampicin; ERY: Erythromycin; TOB: Tobramycin; DOX: Doxycycline; FUR: Furazolidone; TET: Tetracycline; T/S: Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole; GEN: Gentamicin; NOR: Norfloxacin; CIP: Ciprofloxacin; CHL: Chloramphenicol; FLO: Florfenicol. |

| 图选项 |

2.4 美人鱼发光杆菌耐药性的时空差异 广东分离菌株22株,耐药谱18种,谱型丰富度为0.82;海南分离菌株13株,耐药谱13种,谱型丰富度为1.00;广东的多重耐药率为54.55% (12/22),最多耐药9种,海南的多重耐药率为69.23% (9/13),最多耐药10种(图 4)。因此,海南的谱型丰富度、多重耐药率以及最多耐药数量均大于广东。t检验表明,广东和海南分离菌株的多重耐药指数差异性接近显著(F=3.589,P=0.182),且海南分离菌株的平均多重耐药指数(0.32)高于广东分离菌株的平均多重耐药指数(0.25) (图 5-A)。具体为:阿莫西林、利福平、红霉素、多西环素、呋喃唑酮、四环素、诺氟沙星和环丙沙星的耐药率海南高于广东,其他抗生素的耐药率海南低于广东;但是广东和海南的分离菌株均表现出对万古霉素、阿莫西林、麦迪霉素和利福平的强耐药性;广东菌株对诺氟沙星和环丙沙星不耐受,但海南菌株对两者的耐药率均为15.38% (图 5-B)。

|

| 图 5 菌株耐药时空差异 Figure 5 The spatial and temporal difference of antibiotic resistance. A: Multi-antibiotic resistance index of isolates from Guangdong and Hainan; B: The resistance rate of each antibiotic of isolates from Guangdong and Hainan; C: Multi-antibiotic resistance index of isolates from 2011 to 2014; D: The resistance rate of each antibiotic of isolates from 2011 to 2014. |

| 图选项 |

2011–2014年的分离菌株数分别为5、8、16、6株;耐药谱分别有5、8、15、6种,谱型丰富度依次为1.00、1.00、1.00、0.86。2011–2014年的多重耐药率依次为40.00% (2/5)、87.50% (7/8)、56.25% (9/16)、66.67% (4/6);最多耐药数量依次为4、7、10、6种(图 4)。因此,各年份分离菌株耐药性均有变化。单因素方差分析表明,各年份之间的多重耐药指数差异性不显著(F=0.445,P=0.723) (图 5-C),但是2012年的平均多重耐药指数(0.32)高于2011年(0.23),并在2013年(0.30)和2014年(0.27)逐渐下降,但是维持在相对高于2011年的水平。具体为:2011–2014年的分离菌株均表现出对万古霉素、麦迪霉素和利福平的强耐药性;2014年分离株对阿莫西林的耐药性(16.67%)显著低于其他年份(> 50%);2013年分离株表现出对庆大霉素、诺氟沙星和环丙沙星一定的耐药性(> 10%),但其他年份的分离株均不耐受这3种抗生素(图 5-D)。

3 讨论 美人鱼发光杆菌广泛存在于海水,能够感染多种海洋经济鱼类、甲壳类、软体类动物,并引起大批死亡[1],其流行分布、致病性和耐药性等方面值得关注。病原菌表达并释放毒力因子,进而黏附、侵染和损伤宿主,检测潜在病原菌的毒力基因能为其致病性的评估提供重要依据[30]。研究表明,毒力基因可以是细菌固有的(典型毒力基因),也可以通过水平基因转移获得(非典型毒力基因)[31]。美人鱼发光杆菌高度可塑的基因组使得其很容易通过水平基因转移与其他细菌发生基因交流[32],如美人鱼亚种的pPHDD1质粒含有dly、hlyAp1和hylAch 3个溶血素基因,可通过接合转移在不同细菌之间传播[33]。溶血素基因可以产生引起溶血作用的酶,是病原菌中分布最广的外毒素之一,它能破坏宿主的红细胞膜,导致红细胞内容物溢出引起溶血,在病原菌感染过程中起到重要作用[34]。本研究发现在19株美人鱼发光杆菌中检测到霍乱弧菌(hlyA)、创伤弧菌(vvh)、哈维弧菌(vhh)或副溶血弧菌(tdh和trh)特有的溶血素基因,每株菌检测到1–2个基因。据笔者所知,这是第一次分析不同弧菌溶血素基因在美人鱼发光杆菌中的存在情况,研究结果表明美人鱼发光杆菌可能利用质粒、转座子和整合性接合元件等通过水平转移获得其他弧菌溶血素基因,进而可能增加其毒力并扩宽其宿主范围。具体水平传播机制以及这些溶血素基因对美人鱼发光杆菌的毒力作用需要进一步研究。

抗生素被广泛应用于养殖过程美人鱼发光杆菌病原的预防和治疗。在许多亚欧国家,包括中国、西班牙、日本、法国、意大利、土耳其等,氨苄西林、新霉素、卡那霉素、亚胺培南、红霉素、恶唑酸、四环素、复方新诺明、链霉素、阿莫西林、氯霉素、氟苯尼考、氟美喹、土霉素、硝基呋喃酮、磺胺嘧啶、甲氧苄啶等大量抗生素被应用于美人鱼发光杆菌感染的防控[12]。但抗生素的过度使用,导致细菌耐药机制的发生和发展,从而增强细菌耐药性,并导致多重耐药,对病害防控造成困难。另外,由于美人鱼发光杆菌基因组的高度可塑性,使得其能通过pAQU1、IncFIB等耐药质粒(R质粒)在细菌之间水平传播blaCARB-9-like、floR、mph(A)-like、mef(A)-like、sul2、tet(M)和tet(B)等多种耐药基因[35-36],改变甚至获得耐药性。从土耳其养殖鱼体分离的美人鱼发光杆菌对林可霉素、青霉素G和阿莫西林耐受,但对氟苯尼考、复方新诺明、土霉素和恩诺沙星敏感[37]。日本养殖鱼体分离株,45%以上对红霉素(93%)、氯霉素、卡那霉素、恶唑酸和土霉素耐受,但90%以上对氨苄西林、阿莫西林、氟苯尼考、青霉素、链霉素、复方新诺明敏感;欧洲养殖鱼体分离株42%以上对红霉素(98%)、庆大霉素耐受,但是93%以上对氨苄西林、阿莫西林、氟苯尼考、复方新诺明敏感;美国养殖鱼体分离株对红霉素、恩诺沙星、庆大霉素、恶唑酸耐受,但是对氨苄西林、阿莫西林、氟苯尼考、青霉素、链霉素、复方新诺明敏感[38]。以上研究表明,不同地区美人鱼发光杆菌耐药性的发展有所差异,但是氟苯尼考和复方新诺明对其控制具有效果。笔者研究发现,中国华南沿海地区患病海水鱼分离的美人鱼发光杆菌耐药谱型丰富度达到0.77,多重耐药率(菌株耐抗生素种类 > 3)达到60.00%;对万古霉素、阿莫西林、麦迪霉素、利福平和红霉素的耐药率高于30%;对四环素、呋喃唑酮、复方新诺明、庆大霉素、诺氟沙星和环丙沙星耐药率低于15%;对氯霉素和氟苯尼考完全敏感。研究结果表明,耐药性在中国华南沿海地区分离株中严重发生,并且多样发展,与世界其他地区分离株的耐药结果也有异同。相似的,复方新诺明和氟苯尼考对中国华南地区养殖鱼美人鱼发光杆菌感染的控制有效。此外,庆大霉素、诺氟沙星、环丙沙星和氯霉素也有一定的控制潜力。根据中华人民共和国农业农村部《水产养殖用药明白纸2019年1号》文件,诺氟沙星和氯霉素为水产养殖禁用药品。此外,本研究是体外实验的结果,未来可着重测试复方新诺明、氟苯尼考、庆大霉素和环丙沙星的体内控制效果。

笔者研究发现非典型毒力基因多重毒力基因指数在海南和广东之间以及不同年份之间均无显著差异,但是高检出率的hlyA和vvh基因在海南的检出率高于广东,并随年份增加检出率呈现一定的增加趋势。此外,耐药性分析结果显示,海南的谱型丰富度、多重耐药率、最多耐药数量以及平均多重耐药指数均大于广东。虽然耐药性不随年份增加呈现逐渐变化,但是2012年的平均多重耐药指数高于2011年,并在2013年和2014年维持在相对较高的水平。因此,整体上海南分离菌株非典型毒力基因和耐药性尤其是耐药性高于广东;并且非典型毒力基因和耐药性均一定程度随着年份的增加而增多或者增强。前人研究发现,一定的温度刺激可以直接诱导耐药基因和毒力基因的表达[39]。例如,当温度从15 ℃升高到25 ℃时,美人鱼发光杆菌与铁吸收、外膜蛋白合成、毒素分泌、运动性、耐药泵、趋化性等相关基因表达被上调了2–5倍,同时伴随着细菌毒力和耐药性的增强[40]。此外,温度刺激通过影响生物膜的形成、细胞膜的通透性、免疫系统的活性以及与水平基因转移相关的各种酶活性等,影响水平基因转移,进而影响细菌毒力和耐药性[41]。例如,Bailey等[42]发现,45 ℃热击处理棒状链球菌(Streptomyces clavuligerus),可将其水平基因转移效率提高100倍。此外,美人鱼发光杆菌感染的发生也具有很强的季节性,尤其在温暖的夏季暴发频繁[43]。由于气候温暖,海南成为我国主要的海洋鱼苗产地之一,其年养殖时间比广东长。因此,更长的年养殖时间(代表更长的抗生素使用时间)和相对高的气温很可能导致海南分离菌株非典型毒力基因含量和耐药性强于广东。酸碱和有机污染也被报道能够影响细菌水平基因转移和基因表达等,从而改变细菌的毒性和耐药性[44]。因此,未来笔者将进一步研究病原菌的毒力和耐药性对不同环境胁迫的响应机制。

本研究以中国华南沿海地区患病海水鱼分离的35株美人鱼发光杆菌为研究对象,分析了5个非典型毒力基因(溶血素类基因)在菌株中的分布情况以及菌株对15种抗生素的耐药性,发现:(1)美人鱼发光杆菌可能通过水平基因转移获得其他细菌毒力基因,从而增强其毒力并扩宽其宿主范围;(2)耐药性以及多重耐药性在美人鱼发光杆菌中广泛存在,但是复方新诺明、氟苯尼考、庆大霉素和环丙沙星可能对美人鱼发光杆菌具有一定的控制作用;(3)海南分离菌株的非典型毒力基因含量和耐药性,尤其是耐药性高于广东,并且非典型毒力基因和耐药性随着年份增加,呈现一定的增加和增强的趋势。因此,本研究解析了美人鱼发光杆菌中非典型毒力基因和耐药性的时空变化,揭示水平基因转移可能对毒力和耐药的传播具有重要作用,而高温和抗生素污染等环境胁迫将促进其毒力和耐药性的发生和发展,这些结果将有助于评估美人鱼发光杆菌的致病潜力,并指导该菌所引起的病害防控。为防控美人鱼发光杆菌引起的病害,建议:(1)水产养殖尤其是室内养殖中应注重温度等的生态调控,并降低抗生素尤其是万古霉素、阿莫西林、麦迪霉素、利福平和红霉素等的使用,从而降低毒力和耐药基因的表达,并减弱毒力和耐药性的水平传播;(2)在无其他绿色防控手段的条件下,重点利用复方新诺明和氟苯尼考控制美人鱼发光杆菌引发的病害。未来,建议聚焦以下研究:(1)非典型毒力基因对美人鱼发光杆菌的毒力作用以及体内实验测试低耐药率抗生素对美人鱼发光杆菌感染的防控作用;(2)剧烈人为活动造成环境污染以及全球气候变化背景下,病原菌的毒力和耐药性对不同环境胁迫的响应机制。

References

| [1] | Osorio CR. Photobacterium damselae: How horizontal gene transfer shaped two different pathogenic lifestyles in a marine bacterium//Villa TG, Vi?as M. Horizontal Gene Transfer. Cham: Springer, 2019. |

| [2] | Tao Z, Shen C, Zhou SM, Yang N, Wang GL, Wang YJ, Xu SL. An outbreak of Photobacterium damselae subsp. damselae infection in cultured silver pomfret Pampus argenteus in Eastern China. Aquaculture, 2018, 492: 201-205. DOI:10.1016/j.aquaculture.2018.04.013 |

| [3] | Barnes AC, Dos Santos NMS, Ellis AE. Update on bacterial vaccines:Photobacterium damselae subsp. piscicida. Developments in Biologicals, 2005, 121: 75-84. |

| [4] | Romalde JL. Photobacterium damselae subsp. piscicida:an integrated view of a bacterial fish pathogen. International Microbiology, 2002, 5: 3-9. DOI:10.1007/s10123-002-0051-6 |

| [5] | Essam HM, Abdellrazeq GS, Tayel SI, Torky HA, Fadel AH. Pathogenesis of Photobacterium damselae subspecies infections in sea bass and sea bream. Microbial Pathogenesis, 2016, 99: 41-50. DOI:10.1016/j.micpath.2016.08.003 |

| [6] | Yang N, Zhang ZQ, Wu TL, Wang HB, Shi QM, Gao GS. Isolation and identification of Photobacterium damselae subsp. damselae from Tongue Sole. Chinese Journal of Veterinary Drug, 2018, 52(2): 19-25. (in Chinese) 杨楠, 张志强, 吴同垒, 王洪彬, 史秋梅, 高桂生. 半滑舌鳎源美人鱼发光杆菌美人鱼亚种的分离鉴定. 中国兽药杂志, 2018, 52(2): 19-25. |

| [7] | Labella AM, Arahal DR, Castro D, Lemos ML, Borrego JJ. Revisiting the genus Photobacterium:taxonomy, ecology and pathogenesis. International Microbiology, 2017, 20(1): 1-10. |

| [8] | Terceti MS, Ogut H, Osorio CR. Photobacterium damselae subsp. damselae, an emerging fish pathogen in the Black Sea:evidence of a multiclonal origin. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2016, 82(13): 3736-3745. DOI:10.1128/AEM.00781-16 |

| [9] | Terceti MS, Vences A, Matanza XM, Dalsgaard I, Pedersen K, Osorio CR. Molecular epidemiology of Photobacterium damselae subsp. damselae outbreaks in marine rainbow trout farms reveals extensive horizontal gene transfer and high genetic diversity. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2018, 9: 2155. DOI:10.3389/fmicb.2018.02155 |

| [10] | Souto A, Montaos MA, Rivas AJ, Balado M, Osorio CR, Rodríguez J, Lemos ML, Jiménez C. Structure and biosynthetic assembly of piscibactin, a siderophore from Photobacterium damselae subsp. piscicida, predicted from genome analysis. European Journal of Organic Chemistry, 2012, 2012(29): 5693-5700. |

| [11] | Mo WY, Chen ZT, Leung HM, Leung AOW. Application of veterinary antibiotics in China's aquaculture industry and their potential human health risks. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 2017, 24(10): 8978-8989. DOI:10.1007/s11356-015-5607-z |

| [12] | Santos L, Ramos F. Antimicrobial resistance in aquaculture:current knowledge and alternatives to tackle the problem. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents, 2018, 52(2): 135-143. DOI:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2018.03.010 |

| [13] | Abdel-Aziz M, Eissa AE, Hanna M, Okada MA. Identifying some pathogenic Vibrio/Photobacterium species during mass mortalities of cultured Gilthead seabream (Sparus aurata) and European seabass (Dicentrarchus labrax) from some Egyptian coastal provinces. International Journal of Veterinary Science and Medicine, 2013, 1(2): 87-95. DOI:10.1016/j.ijvsm.2013.10.004 |

| [14] | Frans I, Michiels CW, Bossier P, Willems KA, Lievens B, Rediers H. Vibrio anguillarum as a fish pathogen:virulence factors, diagnosis and prevention. Journal of Fish Diseases, 2011, 34(9): 643-661. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2761.2011.01279.x |

| [15] | Pruden A, Larsson DGJ, Amézquita A, Collignon P, Brandt KK, Graham DW, Lazorchak JM, Suzuki S, Silley P, Snape JR, Topp E, Zhang T, Zhu YG. Management options for reducing the release of antibiotics and antibiotic resistance genes to the environment. Environmental Health Perspectives, 2013, 121(8): 878-885. DOI:10.1289/ehp.1206446 |

| [16] | Zhang QQ, Ying GG, Pan CG, Liu YS, Zhao JL. Comprehensive evaluation of antibiotics emission and fate in the river basins of China:source analysis, multimedia modeling, and linkage to bacterial resistance. Environmental Science & Technology, 2015, 49(11): 6772-6782. |

| [17] | Scarano C, Spanu C, Ziino G, Pedonese F, Dalmasso A, Spanu V, Virdis S, de Santis EP. Antibiotic resistance of Vibrio species isolated from Sparus aurata reared in Italian mariculture. The New Microbiologica, 2014, 37(3): 329-337. |

| [18] | He Y, Jin LL, Sun FJ, Hu QX, Chen LM. Antibiotic and heavy-metal resistance of Vibrio parahaemolyticus isolated from fresh shrimps in Shanghai fish markets, China. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 2016, 23(15): 15033-15040. DOI:10.1007/s11356-016-6614-4 |

| [19] | Chiu TH, Kao LY, Chen ML. Antibiotic resistance and molecular typing of Photobacterium damselae subsp. damselae, isolated from seafood. Journal of Applied Microbiology, 2013, 114(4): 1184-1192. DOI:10.1111/jam.12104 |

| [20] | Fisheries and Fisheries Administration of Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of the People's Republic of China, National Fisheries Technology Extension Center, China Society of Fisheries. 2019 China fishery statistical yearbook. Beijing: China Agricultural Machinery Press, 2019. (in Chinese) 农业农村部渔业渔政管理局, 全国水产技术推广总站, 中国水产学会.中国渔业统计年鉴-2019.北京: 中国农业出版社, 2019. |

| [21] | Lages MA, Balado M, Lemos ML. The expression of virulence factors in Vibrio anguillarum is dually regulated by iron levels and temperature. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2019, 10: 2335. DOI:10.3389/fmicb.2019.02335 |

| [22] | Mohamad N, Amal MNA, Yasin ISM, Saad MZ, Nasruddin NS, Al-saari N, Mino S, Sawabe T. Vibriosis in cultured marine fishes:a review. Aquaculture, 2019, 512: 734289. DOI:10.1016/j.aquaculture.2019.734289 |

| [23] | Saravanan V, Kumar HS, Karunasagar I, Karunasagar I. Putative virulence genes of Vibrio cholerae from seafoods and the coastal environment of Southwest India. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 2007, 119: 329-333. DOI:10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2007.08.023 |

| [24] | Tada J, Ohashi T, Nishimura N, Shirasaki Y, Ozaki H, Fukushima S, Takano J, Nishibuchi M, Takeda Y. Detection of the thermostable direct hemolysin gene (tdh) and the thermostable direct hemolysin-related hemolysin gene (trh) of Vibrio parahaemolyticus by polymerase chain reaction. Molecular and Cellular Probes, 1992, 6(6): 477-487. DOI:10.1016/0890-8508(92)90044-X |

| [25] | Lee JY, Bang YB, Rhee JH, Choi SH. Two-stage nested PCR effectiveness for direct detection of Vibrio vulnificus in natural samples. Journal of Food Science, 1999, 64(1): 158-162. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2621.1999.tb09882.x |

| [26] | Meena R, Jangir K, Maherchandani S, Meena BS, Gangwal A, Boyal PK, Kashyap SK. Isolation, identification and Multiple Antibiotic Resistance (MAR) indices of commensal Escherichia coli isolated from healthy chicks. Veterinary Practitioner, 2016, 17(2): 166-168. |

| [27] | Ministry of Health of the People's Republic of China. WS/T 125-1999 Standard of antidbiotics susceptibility test (kirby-bauer method). Beijing: StandardsPress of China, 2000. (in Chinese) 中华人民共和国卫生部. WS/T 125-1999纸片法抗菌药物敏感试验标准.北京: 中国标准出版社, 2000. |

| [28] | Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Twenty-First Informational Supplement M100-S21. 2011. |

| [29] | Wagner WE. Using IBM SPSS statistics for research methods and social science statistics. Los Angeles: Sage Publications, Inc., 2016. |

| [30] | Ina-Salwany MY, Al-saari N, Mohamad A, Mursidi FA, Mohd-Aris A, Amal MNA, Kasai H, Mino S, Sawabe T, Zamri-Saad M. Vibriosis in fish:a review on disease development and prevention. Journal of Aquatic Animal Health, 2019, 31(1): 3-22. DOI:10.1002/aah.10045 |

| [31] | Schroeder M, Brooks BD, Brooks AE. The complex relationship between virulence and antibiotic resistance. Genes, 2017, 8(1): 39. |

| [32] | Gogarten JP, Townsend JP. Horizontal gene transfer, genome innovation and evolution. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 2005, 3(9): 679-687. DOI:10.1038/nrmicro1204 |

| [33] | Rivas AJ, Labella AM, Borrego JJ, Lemos ML, Osorio CR. Evidence for horizontal gene transfer, gene duplication and genetic variation as driving forces of the diversity of haemolytic phenotypes in Photobacterium damselae subsp. damselae. FEMS Microbiology Letters, 2014, 355(2): 152-162. DOI:10.1111/1574-6968.12464 |

| [34] | Mizuno T, Debnath A, Miyoshi S. Hemolysin of vibrio species. London: Intech Open, 2019. |

| [35] | Nonaka L, Maruyama F, Miyamoto M, Miyakoshi M, Kurokawa K, Masuda M. Novel conjugative transferable multiple drug resistance plasmid pAQU1 from Photobacterium damselae subsp. damselae isolated from marine aquaculture environment. Microbes and Environments, 2012, 27(3): 263-272. DOI:10.1264/jsme2.ME11338 |

| [36] | Del Castillo CS, Jang HB, Hikima JI, Jung TS, Morii H, Hirono I, Kondo H, Kurosaka C, Aoki T. Comparative analysis and distribution of pP9014, a novel drug resistance IncP-1 plasmid from Photobacterium damselae subsp. piscicida. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents, 2013, 42(1): 10-18. DOI:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2013.02.027 |

| [37] | Türe M, Alp H. Identification of bacterial pathogens and determination of their antibacterial resistance profiles in some cultured fish in Turkey. Journal of Veterinary Research, 2016, 60(2): 141-146. DOI:10.1515/jvetres-2016-0020 |

| [38] | Thyssen A, Ollevier F. In vitro antimicrobial susceptibility of Photobacterium damselae subsp. piscicida to 15 different antimicrobial agents. Aquaculture, 2001, 200(3/4): 259-269. |

| [39] | Guijarro JA, Cascales D, García-Torrico AI, García-Domínguez M, Méndez J. Temperature-dependent expression of virulence genes in fish-pathogenic bacteria. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2015, 6: 700. |

| [40] | Matanza XM, Osorio CR. Transcriptome changes in response to temperature in the fish pathogen Photobacterium damselae subsp. damselae:clues to understand the emergence of disease outbreaks at increased seawater temperatures. PLoS One, 2018, 13(12): e0210118. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0210118 |

| [41] | Fuchsman CA, Collins RE, Rocap G, Brazelton WJ. Effect of the environment on horizontal gene transfer between bacteria and archaea. PeerJ, 2017, 5: e3865. DOI:10.7717/peerj.3865 |

| [42] | Bailey CR, Winstanley DJ. Inhibition of restriction in Streptomyces clavuligerus by heat treatment. Journal of General Microbiology, 1986, 132(10): 2945-2947. |

| [43] | Baker-Austin C, Oliver JD, Alam M, Ali A, Waldor MK, Qadri F, Martinez-Urtaza J. Vibrio spp. infections. Nature Reviews Disease Primers, 2018, 4(1): 8. DOI:10.1038/s41572-018-0005-8 |

| [44] | Sch?fer A, Kalinowski J, Pühler A. Increased fertility of Corynebacterium glutamicum recipients in intergeneric matings with Escherichia coli after stress exposure. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 1994, 60(2): 756-759. DOI:10.1128/AEM.60.2.756-759.1994 |