), 谭潇1, 谢志杰1

), 谭潇1, 谢志杰1 1华中师范大学心理学院暨社会心理研究中心

2青少年网络心理与行为教育部重点实验室, 武汉 430079

收稿日期:2020-05-25出版日期:2021-04-25发布日期:2021-02-22通讯作者:温芳芳E-mail:wenff@mail.ccnu.edu.cn基金资助:*国家社会科学基金重大项目(18ZDA331);*华中师范大学基本科研业务费项目(CCNU19ZN021)The impact of gender orientation of names on individuals’ evaluation of impressions and interpersonal interaction

ZUO Bin1,2, LIU Chen1,2, WEN Fangfang1,2( ), TAN Xiao1, XIE Zhijie1

), TAN Xiao1, XIE Zhijie1 1School of Psychology, Center for Studies of Social Psychology, Central China Normal University, Wuhan 430079, China

2Key Laboratory of Adolescent Cyberpsychology and Behavior, Ministry of Education, Central China Normal University, Wuhan 430079, China

Received:2020-05-25Online:2021-04-25Published:2021-02-22Contact:WEN Fangfang E-mail:wenff@mail.ccnu.edu.cn摘要/Abstract

摘要: 名字在个体印象评价和人际交往中发挥着重要作用。本研究结合刻板印象内容模型, 从刻板印象维护视角出发, 通过3个研究考察了性别化名字的热情能力感知, 基于此探究性别化名字对不同性别个体的印象评价及人际交往的影响。结果发现:(1)人们对男性化名字的能力评价高于女性化名字, 对女性化名字的热情评价高于男性化名字; (2)性别化名字影响男性的能力评价和女性的热情评价; (3)性别化名字影响人们对女性的交友偏好, 热情评价在其中起到完全中介作用; 性别化名字影响人们和男性的共事偏好, 能力评价起到完全中介作用。研究揭示了性别化名字影响印象评价的模式, 并为理解人际交往中名字的作用机制提供了新的研究思路。

图/表 6

表1对不同性别化名字的男性和女性的热情与能力评价(M ± SD)

| 个体性别 | 男性化名字 | 女性化名字 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 热情 | 能力 | 热情 | 能力 | |||||

| 男性 | 4.98 ± 0.89 | 5.40 ± 0.75 | 4.95 ± 0.97 | 4.80 ± 1.14 | ||||

| 女性 | 4.85 ± 0.99 | 5.32 ± 0.93 | 5.31 ± 0.96 | 5.26 ± 0.99 | ||||

表1对不同性别化名字的男性和女性的热情与能力评价(M ± SD)

| 个体性别 | 男性化名字 | 女性化名字 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 热情 | 能力 | 热情 | 能力 | |||||

| 男性 | 4.98 ± 0.89 | 5.40 ± 0.75 | 4.95 ± 0.97 | 4.80 ± 1.14 | ||||

| 女性 | 4.85 ± 0.99 | 5.32 ± 0.93 | 5.31 ± 0.96 | 5.26 ± 0.99 | ||||

图1对不同性别化名字男女个体的热情能力评分 注:*表示p < 0.05, **表示 p < 0.01, ***表示 p < 0.001,“男名”为“男性化名字”, “女名”为“女性化名字”, 下图同

图1对不同性别化名字男女个体的热情能力评分 注:*表示p < 0.05, **表示 p < 0.01, ***表示 p < 0.001,“男名”为“男性化名字”, “女名”为“女性化名字”, 下图同

图1对不同性别化名字男女个体的热情能力评分 注:*表示p < 0.05, **表示 p < 0.01, ***表示 p < 0.001,“男名”为“男性化名字”, “女名”为“女性化名字”, 下图同 表2研究3a、3b不同性别化名字人物的热情、能力评价(M ± SD)

| 名字维度 | 研究3a (交友情境) | 研究3b (任务情境) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 男性 | 女性 | 男性 | 女性 | |

| 男名热情 | 4.73 ± 0.98 | 4.47 ± 1.02 | 4.56 ± 0.97 | 4.55 ± 0.97 |

| 男名能力 | 4.83 ± 1.00 | 4.97 ± 0.99 | 5.09 ± 1.10 | 5.27 ± 0.91 |

| 女名热情 | 4.78 ± 0.97 | 5.41 ± 0.80 | 4.85 ± 0.84 | 5.42 ± 0.81 |

| 女名能力 | 4.49 ± 0.73 | 4.90 ± 0.78 | 4.70 ± 0.81 | 5.04 ± 0.95 |

表2研究3a、3b不同性别化名字人物的热情、能力评价(M ± SD)

| 名字维度 | 研究3a (交友情境) | 研究3b (任务情境) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 男性 | 女性 | 男性 | 女性 | |

| 男名热情 | 4.73 ± 0.98 | 4.47 ± 1.02 | 4.56 ± 0.97 | 4.55 ± 0.97 |

| 男名能力 | 4.83 ± 1.00 | 4.97 ± 0.99 | 5.09 ± 1.10 | 5.27 ± 0.91 |

| 女名热情 | 4.78 ± 0.97 | 5.41 ± 0.80 | 4.85 ± 0.84 | 5.42 ± 0.81 |

| 女名能力 | 4.49 ± 0.73 | 4.90 ± 0.78 | 4.70 ± 0.81 | 5.04 ± 0.95 |

图2交友、任务情境下被试对不同性别化名字男女个体的热情、能力评分

图2交友、任务情境下被试对不同性别化名字男女个体的热情、能力评分

图2交友、任务情境下被试对不同性别化名字男女个体的热情、能力评分

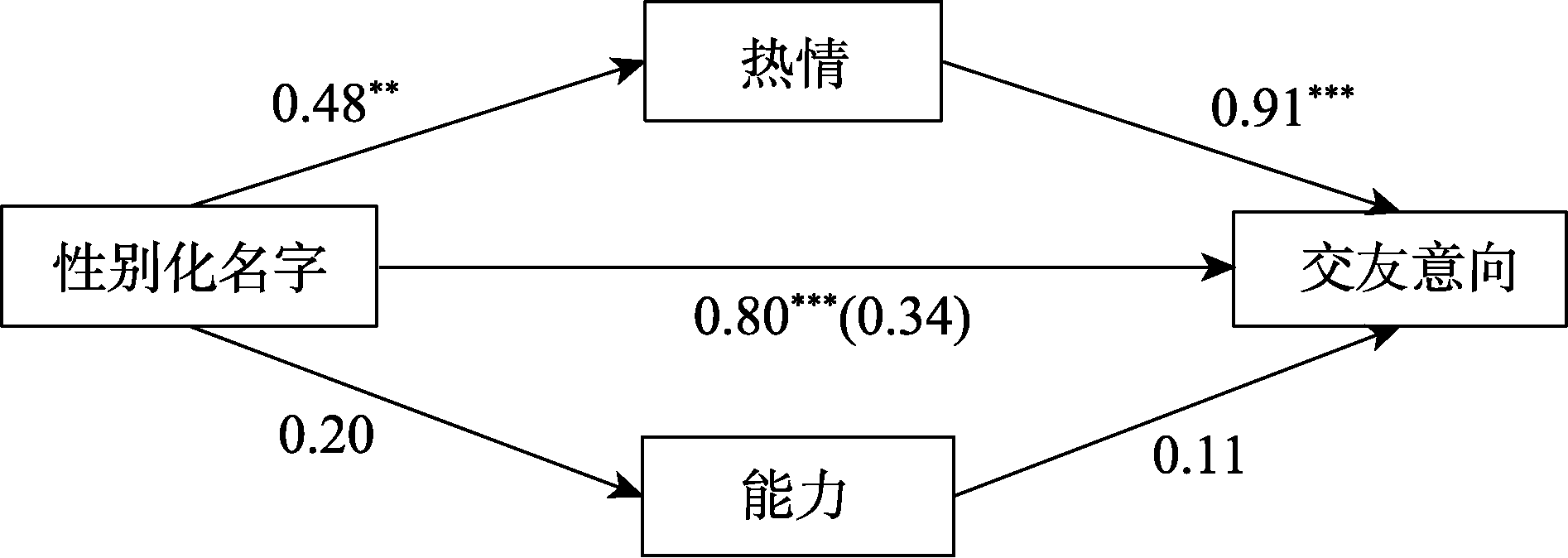

图3名字性别化对女性人物交友意向的中介模型图

图3名字性别化对女性人物交友意向的中介模型图

图3名字性别化对女性人物交友意向的中介模型图

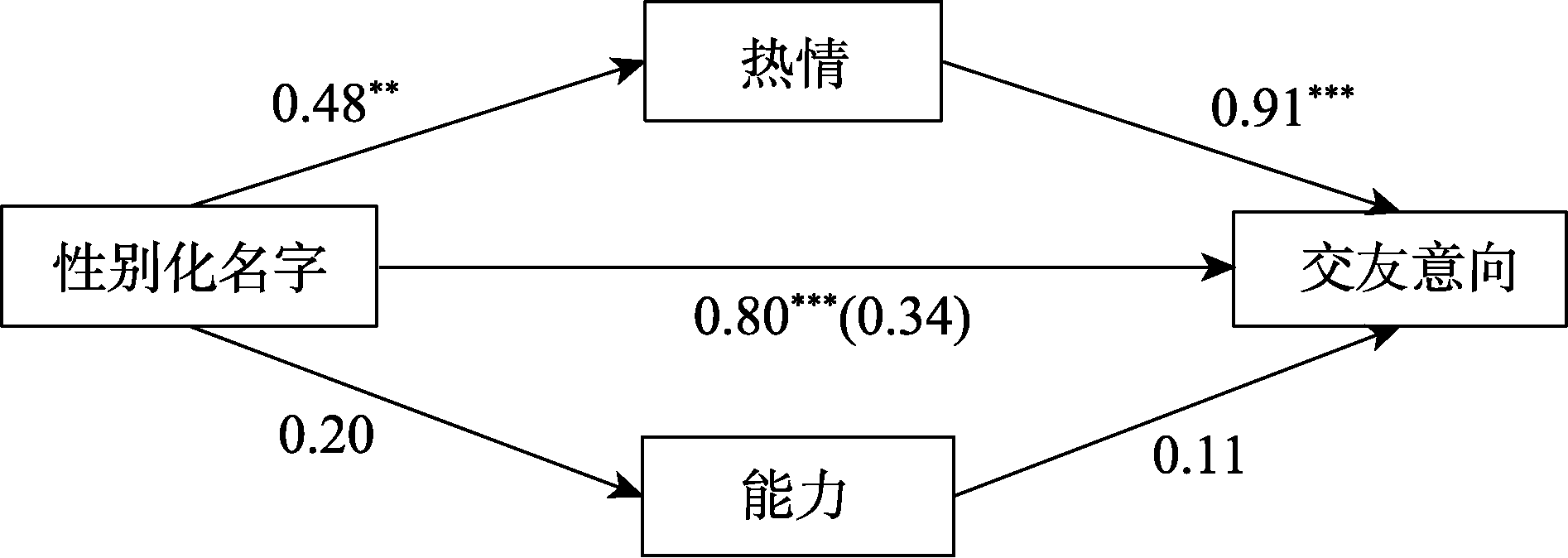

图4名字性别化对男性人物合作意向的中介模型

图4名字性别化对男性人物合作意向的中介模型

图4名字性别化对男性人物合作意向的中介模型参考文献 51

| [1] | Abele,A.E.,& Wojciszke,B. (2007). Agency and communion from the perspective of self versus others. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93(5),751-763. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.93.5.751URLpmid: 17983298 |

| [2] | Bao,H.W. S., Chen,J.L. Lin,J. L.,& Li,L. (2016). Effects of name and gender on interpersonal attraction: Gender role evaluation as a mediator. Chinese Journal of Clinical Psychology, 24(4),596-600. |

| 包寒吴霜, 陈俊霖, 林俊利, 刘力. (2016). 名字与性别的人际吸引机制:性别角色评价的中介作用. 中国临床心理学杂志, 24(4),596-600. | |

| [3] | Benson,A.J., Azizi,E., Evans,M.B. Eys,M. A.,& Bray,S.R. (2019). How innuendo shapes impressions of task and intimacy groups. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 85,1038-1054. |

| [4] | Bosak,J., Eagly,A.H., Diekman,A.B., & Sczesny,S. (2018). Women and men of the past, present, and future: Evidence of dynamic gender stereotypes in Ghana. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 49(1),115-129. doi: 10.1177/0022022117738750URL |

| [5] | Bosak,J., Kulich,C., Rudman,L., & Kinahan,M. (2018). Be an advocate for others, unless you are a man: Backlash against gender-atypical male job candidates. Psychology of Men and Masculinity, 19(1),156-165. doi: 10.1037/men0000085URL |

| [6] | Carrier,A., Dompnier,B., & Yzerbyt,V. (2019). Of nice and mean: The personal relevance of others’ competence drives perceptions of warmth. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 45(11),1549-1562. doi: 10.1177/0146167219835213URLpmid: 30885051 |

| [7] | Clough,P.D., Bates,J., & Otterbacher,J. (2017). Competent men and warm women: Gender stereotypes and backlash in image search results. Computer and Human Interaction, 5,6620-6631. |

| [8] | Coffey,B., & Mclaughlin,P.A. (2009). Do masculine names help female lawyers become judges? Evidence from south carolina. American Law and Economics Review, 11(1),112-133. doi: 10.1093/aler/ahp008URL |

| [9] | Coffey,B., & Mclaughlin,P.A. (2016). The effect on lawyers income of gender information contained in first names. Review of Law and Economics, 12(1),57-76. |

| [10] | Cotton,J.L., O'neill,B. S.,& Griffin,A. (2008). The “name game”: Affective and hiring reactions to first names. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 23(1),18-39. doi: 10.1108/02683940810849648URL |

| [11] | Croft,A., Schmader,T., & Block,K. (2015). An underexamined inequality: Cultural and psychological barriers to men’s engagement with communal roles. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 19(4),343-370. doi: 10.1177/1088868314564789URLpmid: 25576312 |

| [12] | Deaux,K., & Major,B. (1987). Putting gender into context: An interactive model of gender-related behavior. Psychological review, 94(3),369-389. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.94.3.369URL |

| [13] | Duffy,J.C., & Ridinger,B. (1981). Stereotyped connotations of masculine and feminine names. Sex Roles, 7(1),25-33. doi: 10.1007/BF00290895URL |

| [14] | Eagly,A.H. (1987). Sex differences in social behavior. A social-role interpretation. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. |

| [15] | Eagly,A.H., Nater,C., Miller,D.I., Kaufmann,M., & Sczesny,S. (2020). Gender stereotypes have changed: A cross-temporal meta-analysis of U.S. public opinion polls from 1946 to 2018. American Psychologist, 75(3),301-315. doi: 10.1037/amp0000494URL |

| [16] | Ellemers,N. (2018). Gender stereotypes. Annual Review of Psychology, 69(1),275-298. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-122216-011719URL |

| [17] | Etaugh,C., & Geraghty,C. (2018). Both gender and cohort affect perceptions of forenames, but are 25-year-old standards still valid? Sex Roles, 79(11-12),726-737. |

| [18] | Fiske,S.T. (2018). Stereotype content: Warmth and competence endure. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 27(2),67-73. doi: 10.1177/0963721417738825URLpmid: 29755213 |

| [19] | Fiske,S.T., Cuddy,A.J. C., Glick,P., & Xu,J. (2002). A model of (often mixed) stereotype content: Competence and warmth respectively follow from perceived status and competition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82(6),878-902. URLpmid: 12051578 |

| [20] | Fox,E, Russo,R, & Dutton,K. (2002). Attentional bias for threat: Evidence for delayed disengagement from emotional faces. Cognition and Emotion, 16(3),355-379. doi: 10.1080/02699930143000527URLpmid: 18273395 |

| [21] | Glick,P., & Fiske,S.T. (2011). Ambivalent sexism revisited. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 35(3),530-535. doi: 10.1177/0361684311414832URLpmid: 24453402 |

| [22] | Guo,F., Ren,X.P.,& Su,H. (2020). The impact of gender orientation of names on the female applicants' interview opportunity. Human Resources Development of China, 37(5),46-58. |

| 郭凤, 任孝鹏, 苏红. (2020). 不同性别定向的名字对女性获得面试机会的影响. 中国人力资源开发, 37(5),46-58. | |

| [23] | Han,Y., Qiu,J., & Zhang,Q.L. (2008). Conflict effect of gender-stereotypical names and pronouns. Journal of Southwest University (Natural Science Edition), 30(10),164-168. |

| 韩燕, 邱江, 张庆林. (2008). 性别刻板化人名推测判断中的冲突效应. 西南大学学报(自然科学版), 30(10),164-168. | |

| [24] | Hansen,K., Raki?,T., & Steffens,M.C. (2017). Competent and warm? Experimental Psychology, 64(1),27-36. doi: 10.1027/1618-3169/a000348URLpmid: 28219258 |

| [25] | Karniol,R., Artzi,S., & Ludmer,M. (2016). Children’s production of subject-verb agreement in Hebrew when gender and context are ambiguous. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research, 45(6),1515-1532. pmid: 26911992 |

| [26] | Kervyn,N., Bergsieker,H.B., & Fiske,S.T. (2012). The innuendo effect: Hearing the positive but inferring the negative. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 48(1),77-85. doi: 10.1016/j.jesp.2011.08.001URL |

| [27] | Li,Z.X., Zhao,K.B., & Pan,W.J. (2017). The first survey to folk imagination of emperor face in Confucianism. Journal of Psychological Science, 40(3),547-552. |

| 李朝旭, 赵凯宾, 潘文静. (2017). 基于儒家文化的“帝王相”之民间意象的首次探索. 心理科学, 40(3),547-552. | |

| [28] | Lindsay,J.M., & Dempsey,D. (2017). First names and social distinction: Middle-class naming practices in Australia. Journal of Sociology, 53(3),577-591. doi: 10.1177/1440783317690925URL |

| [29] | Liu,X., & Zuo,B. (2006). Psychological mechanism of maintaining gender stereotypes. Advances in Psychological Science, 14(03),456-461. |

| 刘晅, 佐斌. (2006). 性别刻板印象维护的心理机制. 心理科学进展, 14(03),456-461. | |

| [30] | Mccroskey,J.C., & Mccain,T.A. (1974). The measurement of interpersonal attraction. Speech Monographs, 41(3),261-266. doi: 10.1080/03637757409375845URL |

| [31] | Mehrabian,A. (2001). Characteristics attributed to individuals on the basis of their first names. Genetic, Social, and General Psychology Monographs, 127(1),59-88. URLpmid: 11352229 |

| [32] | Montoya,A.K., & Hayes,A.F. (2017). Two-condition within-participant statistical mediation analysis: A path-analytic framework. Psychological Methods, 22(1),6-27. doi: 10.1037/met0000086pmid: 27362267 |

| [33] | Moss‐Racusin,C.A., & Johnson,E.R. (2016). Backlash against male elementary educators. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 46(7),379-393. doi: 10.1111/jasp.12366URL |

| [34] | Nett,T., Dorrough,A., Jekel,M., & Gl?ckner,A. (2020). Perceived biological and social characteristics of a representative set of German first names. Social Psychology, 51(1),17-34. doi: 10.1027/1864-9335/a000383URL |

| [35] | Newman,L.S., Tan, M., Caldwell, T.L., Duff, K. J.,& Winer, E.S.(2018). Name norms: A guide to casting your next experiment. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 44(10),1435-1448. doi: 10.1177/0146167218769858URLpmid: 29739295 |

| [36] | Pilcher,J. (2016). Names, bodies and identities. Sociology, 50(4),764-779. doi: 10.1177/0038038515582157URL |

| [37] | Prentice,D.A., & Carranza,E. (2002). What women and men should be, shouldn't be, are allowed to be, and don't have to be: The contents of prescriptive gender stereotypes. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 26(4),269-281. doi: 10.1111/1471-6402.t01-1-00066URL |

| [38] | Rudman,L.A., Moss-Racusin,C.A., Phelan,J.E., & Nauts,S. (2012). Status incongruity and backlash effects: Defending the gender hierarchy motivates prejudice against female leaders. bJournal of Experimental Social Psychology, 48(1),165-179. |

| [39] | Smith,F.I., Tabak,F., Showail,S., Parks,J.M., & Kleist,J.S. (2005). The name game: Employability evaluations of prototypical applicants with stereotypical feminine and masculine first names. Sex Roles, 52(1),63-82. doi: 10.1007/s11199-005-1194-7URL |

| [40] | Spence,J.T., & Sawin,L.L. (1985). Images of masculinity and femininity: A reconceptualization. In V. E. O'Leary, R.K. Unger, & B. S. Wallston (Eds.),Women, gender, and social psychology (pp. 35-66). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. |

| [41] | Su,H., & Ren,X.P. (2015). Psychological impact of first names: Individual level and group level evidence. Advances in Psychological Science, 23(5),879-887. doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1042.2015.00879URL |

| 苏红, 任孝鹏. (2015). 名字的心理效应:来自个体层面和群体层面的证据. 心理科学进展, 23(5),879-887. doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1042.2015.00879URL | |

| [42] | Vaidis,D., & Bran,A. (2018). Some prior considerations about dissonance to understand its reduction: Comment on McGrath (2017). Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 12(9). 10.1111/spc3.12411. |

| [43] | Wang,D.F., & Cui,H. (2007). Development of Chinese sex role scale and relations between sex role and psychosocial adjustment. Journal of South west University (Social Sciences Edition), 33,1-9. |

| 王登峰, 崔红. (2007). 中国人性别角色量表的建构及其与心理社会适应的关系. 西南大学学报 (社会科学版), 33,1-9. | |

| [44] | Wang,Y., & Wen,Z.L. (2018). The analyses of mediation effects based on two-condition within-participant design. Journal of Psychological Science, 41(5),1233-1239. |

| 王阳, 温忠麟. (2018). 基于两水平被试内设计的中介效应分析方法. 心理科学, 41(5),1233-1239. | |

| [45] | Wen,F.F., & Zuo,B. (2012). The effects of transformed gender facial features on face preference of college students: Based on the test of computer graphics and eye movement tracks. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 44(1),14-29. |

| 温芳芳, 佐斌. (2012). 男性化与女性化对面孔偏好的影响——基于图像处理技术和眼动的检验. 心理学报, 44(1),14-29. | |

| [46] | Wojciszke,B., Bazinska,R., & Jaworski,M. (1998). On the dominance of moral categories in impression formation. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 24(12),1251-1263. doi: 10.1177/01461672982412001URL |

| [47] | Xin,Z.Y. Du,X.P.,& Sha,L. (2015). The influence of trustees’ name recognizability on their trustworthiness. Journal of Psychological Science, 38(6),1438-1444. |

| 辛志勇, 杜晓鹏, 沙璐. (2015). 名字易识认性对被信任者的可信性的影响. 心理科学, 38(6),1438-1444. | |

| [48] | Yang,T., & Ren,X.P. (2016). The impact of gender orientation of names on female mate preferences. Journal of Psychological Science, 39(5),1190-1196. |

| 杨婷, 任孝鹏. (2016). 不同性别定向的名字对女性择偶偏好的影响. 心理科学, 39(5),1190-1196. | |

| [49] | Zhang,J.J., Liu, H.Y.,& Ye, Q.Y.(2006). The influence of names on perceptions of physical attractiveness. Chinese Journal of Applied Psychology, 12(2),127-134. |

| 张积家, 刘红艳, 叶倩仪. (2006). 名字对个体吸引力的影响. 应用心理学, 12(2),127-134. | |

| [50] | Zuo,B., Dai,T.T., Wen, F.F., & Suo Y.X.(2015). The big two model in social cognition. Journal of Psychological Science, 38(4),1019-1023. |

| 佐斌, 代涛涛, 温芳芳, 索玉贤. (2015). 社会认知内容的“大二”模型. 心理科学, 38(4),1019-1023. | |

| [51] | Zuo,B., Dai,T.T., Wen, F. F.,& Teng T. T.(2014). The relationship between warmth and competence in social cognition. Advances in Psychological Science, 22(9),1467-1474. doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1042.2014.01467URL |

| 佐斌, 代涛涛, 温芳芳, 滕婷婷.(2014). 热情与能力的关系及其影响因素. 心理科学进展, 22(9),1467-1474. doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1042.2014.01467URL |

相关文章 15

| [1] | 佐斌, 戴月娥, 温芳芳, 高佳, 谢志杰, 何赛飞. 人如其食:食物性别刻板印象及对人物评价的影响[J]. 心理学报, 2021, 53(3): 259-272. |

| [2] | 尚雪松, 陈卓, 陆静怡. 帮忙失败后我会被差评吗?好心帮倒忙中的预测偏差[J]. 心理学报, 2021, 53(3): 291-305. |

| [3] | 李树文, 罗瑾琏. 领导-下属情绪评价能力一致与员工建言:内部人身份感知与性别相似性的作用[J]. 心理学报, 2020, 52(9): 1121-1131. |

| [4] | 吴翰林, 于宙, 王雪娇, 张清芳. 语言能力的老化机制:语言特异性与非特异性因素的共同作用[J]. 心理学报, 2020, 52(5): 541-561. |

| [5] | 朱振中,刘福,Haipeng (Allan) Chen. 能力还是热情?广告诉求对消费者品牌认同和购买意向的影响[J]. 心理学报, 2020, 52(3): 357-370. |

| [6] | 彭婉晴,罗帏,周仁来. 工作记忆刷新训练改善抑郁倾向大学生情绪调节能力的HRV证据[J]. 心理学报, 2019, 51(6): 648-661. |

| [7] | 陈斯允,卫海英,孟陆. 社会知觉视角下道德诉求方式如何提升劝捐效果[J]. 心理学报, 2019, 51(12): 1351-1362. |

| [8] | 杨群, 张清芳. 汉语图画命名过程的年老化机制:非选择性抑制能力的影响[J]. 心理学报, 2019, 51(10): 1079-1090. |

| [9] | 张明亮, 司继伟, 杨伟星, 邢淑芬, 李红霞, 张佳佳. BDNF基因rs6265多态性与父母教育卷入对小学儿童基本数学能力的交互作用[J]. 心理学报, 2018, 50(9): 1007-1017. |

| [10] | 孙鑫,黎坚,符植煜. 利用游戏log-file预测学生推理能力和数学成绩——机器学习的应用[J]. 心理学报, 2018, 50(7): 761-770. |

| [11] | 韦庆旺, 李木子, 陈晓晨. 社会阶层与社会知觉:热情和能力哪个更重要?[J]. 心理学报, 2018, 50(2): 243-252. |

| [12] | 佐斌,温芳芳,吴漾,代涛涛. 群际评价中热情与能力关系的情境演变:评价意图与结果的作用[J]. 心理学报, 2018, 50(10): 1180-1196. |

| [13] | 刘湍丽, 白学军. 部分线索对记忆提取的影响:认知抑制能力的作用[J]. 心理学报, 2017, 49(9): 1158-1171. |

| [14] | 王燕, 侯博文, 李歆瑶, 李晓煦, 焦璐. 不同性别比和资源获取能力 对未婚男性择偶标准的影响[J]. 心理学报, 2017, 49(9): 1195-1205. |

| [15] | 谈晨皓, 王沛, 崔诣晨. 我会在谁面前舍弃利益? ——博弈对象的能力与社会距离对名利 博弈倾向的影响[J]. 心理学报, 2017, 49(9): 1206-1218. |

PDF全文下载地址:

http://journal.psych.ac.cn/xlxb/CN/article/downloadArticleFile.do?attachType=PDF&id=4913