,

, ,1,2,4,*, 李臻3, 辛智鸣3, 刘明虎3, 李艳丽1,2,4, 郝玉光31

,1,2,4,*, 李臻3, 辛智鸣3, 刘明虎3, 李艳丽1,2,4, 郝玉光31 2

3

4

Effects of leaf shape plasticity on leaf surface temperature

LI Yong-Hua ,

, ,1,2,4,*, LI Zhen3, XIN Zhi-Ming3, LIU Ming-Hu3, LI Yan-Li1,2,4, HAO Yu-Guang31

,1,2,4,*, LI Zhen3, XIN Zhi-Ming3, LIU Ming-Hu3, LI Yan-Li1,2,4, HAO Yu-Guang31 2

3

4

通讯作者:

| 基金资助: |

Online:2018-04-19

| Supported by: | SupportedbytheCentralPublic-interestScientificInstitutionBasalResearchFund.( |

摘要

关键词:

Abstract

Keywords:

PDF (2209KB)摘要页面多维度评价相关文章导出EndNote|Ris|Bibtex收藏本文

引用本文

李永华, 李臻, 辛智鸣, 刘明虎, 李艳丽, 郝玉光. 形态变化对叶片表面温度的影响. 植物生态学报, 2018, 42(2): 202-208 doi:10.17521/cjpe.2017.0127

LI Yong-Hua, LI Zhen, XIN Zhi-Ming, LIU Ming-Hu, LI Yan-Li, HAO Yu-Guang.

叶片温度作为影响叶片光合、呼吸(Mebrahtu et al., 1991; Wise et al., 2004; Juurola et al., 2005)、水分生理(Konis, 1950; Will et al., 2013)、叶肉组织活性(Lambers et al., 1998)的关键因子, 一直是植物学研究的重点。长期以来, 前人使用数学模型(Smith & Geller, 1980; Nobel, 2005)、仿真模拟(Roth-Nebelsick, 2001; Stokes et al., 2006; Vogel, 2009)、 样地测定(Liu et al., 2011)、同位素技术(Helliker & Richter, 2008)

等研究手段, 探索研究了叶片表面温度变化与环境、蒸发、叶片形态的关系。研究结果表明, 叶片温度除受环境因子和蒸腾因素影响外, 也与叶片形态密切相关(Smith & Geller, 1980; Nobel, 2005; Vogel, 2009)。

叶片形态变化对能量(及物质)流动速率的影响决定于叶片表面边界层阻力(Schuepp, 1993; Nobel, 2005)。植物叶面积减小(叶片宽度降低)有利于降低叶片边界层阻力, 增加叶片表面能量与环境的交换速率(Nobel, 2005)。在高辐射及水分限制逐步加强的过程中, 气孔调节功能(蒸腾作用)出现减弱甚至消失的现象。叶面积(叶宽)降低, 不仅可以减少植物总的水分蒸腾量, 而且可以降低叶片表面温度(Smith & Geller, 1980), 由此避免或减少高温对叶片光合系统及叶肉组织的伤害(Wise et al., 2004)。因此, 叶片形态变化也是植物优化限制资源利用, 提高自身生存与适应能力的重要方式(Lambers et al., 1998; Westoby et al., 2002)。

如何在复杂的生物物理过程中准确测定叶片表面温度一直是研究的难点。以往研究中, 常以热电阻或热电偶测定叶片温度(Vogel, 1968, 2009), 但受叶片表面温度分布不均, 热探针固有缺陷(如材料、体积、采集器精度等), 叶片结构与生理过程复杂(如厚度、柔韧性、蒸腾速率等)等因素影响, 一方面无法快速准确地测定叶片表面温度, 另一方面无法准确获取形态、蒸腾等因子对叶温地调控能力, 导致无法进一步理解叶片形态变化对叶温的影响力。

近年来, 红外热成像测温技术的逐步成熟(Jones, 2005; Stokes et al., 2006), 为快速准确测定叶片表面温度提供了帮助; 而小型便携光合测定系统(如LI-6400、LI-6800)的广泛应用, 也为快速测定叶片蒸腾等提供了技术支撑。在前人研究的基础上, 本研究应用光合测定系统与红外热成像技术, 通过测定植物叶片形态、温度、蒸腾及对应环境参数, 展示了干旱区植物叶片形态与蒸腾对叶片温度的共同调控作用, 同时应用模拟叶片进一步检验了单独形态变化对叶温的影响力。

由于全缘叶或具有小裂齿的叶片, 形态参数间存在显著的自相关性。在前人研究的基础上, 本文选取叶片宽度作为表征叶片形态的基础参数, 关注叶片宽度对叶温的影响, 以此阐述形态对叶片温度的重要影响。

1 材料和方法

1.1 野外数据测定

为了确保叶片形态变化显著, 同时验证不同生活型植物叶片形态对叶片温度影响的普遍性, 2016年7月29日, 在晴朗天气背景下, 我们在中国林业科学研究院沙漠林业实验中心实验二场沙地与农田交错区(内蒙古自治区磴口县, 40.45° N, 106.75° E), 选择2种人工栽培乔木: 青杨(Populus cathayana)、沙枣(Elaeagnus angustifolia), 2种野生灌木: 白刺(Nitraria tangutorum)、小果白刺(Nitraria sibirica), 4种草本植物: 灰绿藜(Chenopodium glaucum)、艾(Artemisia argyi)、苍耳(Xanthium sibiricum)、向日葵(Helianthus annuus)(向日葵为人工栽培种, 另外3种为本地野生物种), 每种植物随机选择3株, 每株植物选择1片叶子(通过目视辨识, 确保每种植物3片叶子大小与形态相近似)。在12:00、14:00、16:00左右, 首先通过红外热成像仪(Testo 875-1, TESTO, Lenzkirch, Germany)拍摄叶片红外图像, 并应用专业图像分析软件(Testo IRSoft, TESTO, Lenzkirch, Germany)获取叶片温度, 随后通过光合仪(LI-6400, LI-COR, Lincoln, USA), 标准叶室测定叶片蒸腾速率。同步环境数据(总辐射仪安装高度为10 m, 风速仪安装高度为1 m, 气温仪安装高度为1 m)通过附近(距离样地20 m)的自动气象站获取。测定完成后, 采集叶片, 通过图片扫描(Canon LiDE120, Canon, Tokyo, Japan)、分析(Image-Pro Plus 6.0, Olympus, Tokyo, Japan), 获取叶片面积、周长、最大宽度等形态参数。叶片形态参数间的相关关系见表1。Table 1

表1

表1叶片形态参数间的相关分析

Table 1

| 周长 Perimeter | 面积 Area | 长度 Length | 最大宽度 Maximum width | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 周长 Perimeter | 1.00 | |||

| 面积 Area | 0.79* | 1.00 | ||

| 长度 Length | 0.82** | 0.91** | 1.00 | |

| 最大宽度 Maximum width | 0.94** | 0.89** | 0.79* | 1.00 |

新窗口打开|下载CSV

野外数据测定时段(2016年7月29日12:00- 17:00), 平均气温34.7 ℃、平均相对湿度32.3%、平均风速0.82 m·s-1、平均辐射894.9 W·m-2。

1.2 模拟测定

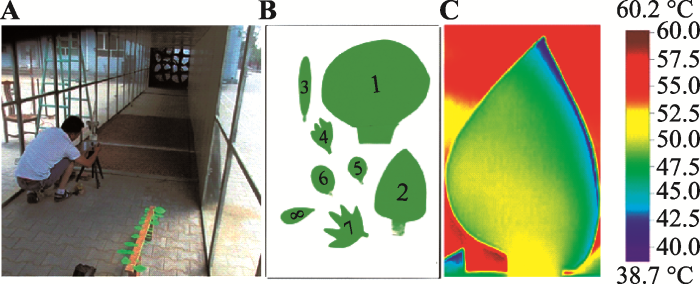

为剔除蒸腾等叶片生理因素对叶温的影响, 进一步测试形态变化对叶温的影响,我们在中国林业科学研究院沙漠林业实验中心风洞内对模拟叶片温度进行了测定(图1A)。模拟叶片以厚度均匀的浅绿色硬纸片为材料, 厚度约0.2 mm。本研究共剪取16个形态不同的模拟叶片, 图1B展示了其中8片叶子的形态特征。模拟叶片被粘在窄木条上, 木条距离地面4 cm, 同时保证每片叶子与地表平行, 以获取相同的辐射等环境条件。测定过程中设定6组风速(0、1、2、3、4和5 m·s-1)。测定区域的实际环境指标通过风洞内微型气象站获取(辐射、风速、气温测试探头高度距离地表0.5 m)。叶片温度、形态的测定方法与真实叶片相同。另外, 相关分析表明真实叶片的叶片面积、周长、长度、最大宽度间的相关关系也十分显著(相关性r = 0.50-0.93, p < 0.01)。图1

新窗口打开|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT

新窗口打开|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT图1A, 风洞中测试模拟叶片的表面温度。B, 模拟叶片形态。C, 模拟叶片的热成像图片。

Fig. 1A, Surface temperature measurement of simulated leaf in a wind tunnel. B, Leaf shape of simulated leaf. C, A thermal image of a simulated leaf.

1.3 数据分析

本研究利用SPSS 18.0数据分析软件(SPSS, Chicago, USA)计算了叶片最大宽度、长度、面积、周长的平均值及其对应的标准偏差, 分析了真实叶片与模拟叶片最大宽度、长度、面积、周长间的相关关系, 并将蒸腾、形态对叶温的影响进行了多元线性回归分析。在Origin 8.5软件环境下绘图并应用简单线性回归法拟合了叶片宽度、环境因子对叶片温度的影响。2 结果和分析

2.1 形态与蒸腾对叶片温度的影响

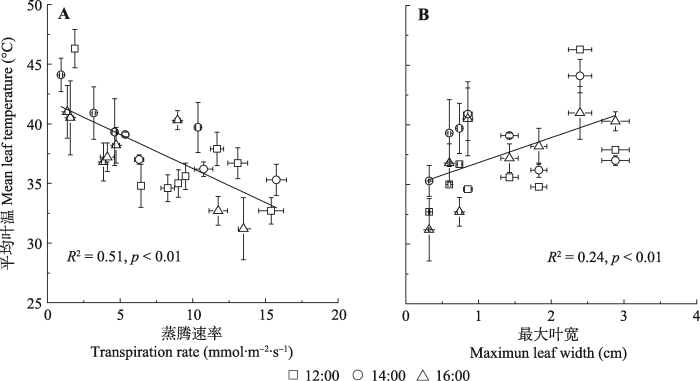

蒸腾是调控叶片表面温度的主要因子。简单线性回归分析表明, 随蒸腾速率的增加, 叶片温度呈现降低趋势(图2A)。12:00、14:00、16:00蒸腾速率变化分别解释了叶片温度的36.7% (p < 0.1)、57.5% (p < 0.05)和5.2% (p < 0.3); 3次测试数据汇总后, 蒸腾能够解释叶片温度变化的51% (p < 0.01)(图2A), 蒸腾速率每增加1 mmol·m-2·s-1, 叶片温度降低0.57 ℃。形态变化对叶片表面温度的影响也十分显著。简单线性拟合显示, 随叶片宽度的增加, 叶片温度呈现增加趋势(图2B)。12:00、14:00、16:00叶片宽度分别解释了叶片温度变化的37.0% (p < 0.1)、5.9% (p < 0.3)和68.5% (p < 0.01); 3次测试数据汇总后, 叶片宽度能够解释叶片温度变化的24% (p < 0.05) (图2B), 叶片宽度每减少1 cm, 叶片表面温度降低约2.1 ℃。3次测试数据的多元线性回归分析表明, 叶片宽度和蒸腾能够联合解释叶片表面温度变化的56% (p < 0.01)。

图2

新窗口打开|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT

新窗口打开|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT图2蒸腾、叶宽对叶片温度的影响(平均值±标准误差)。

Fig. 2Empirical relationships between maximal leaf width, leaf transpiration rate and leaf temperature (mean ± SE).

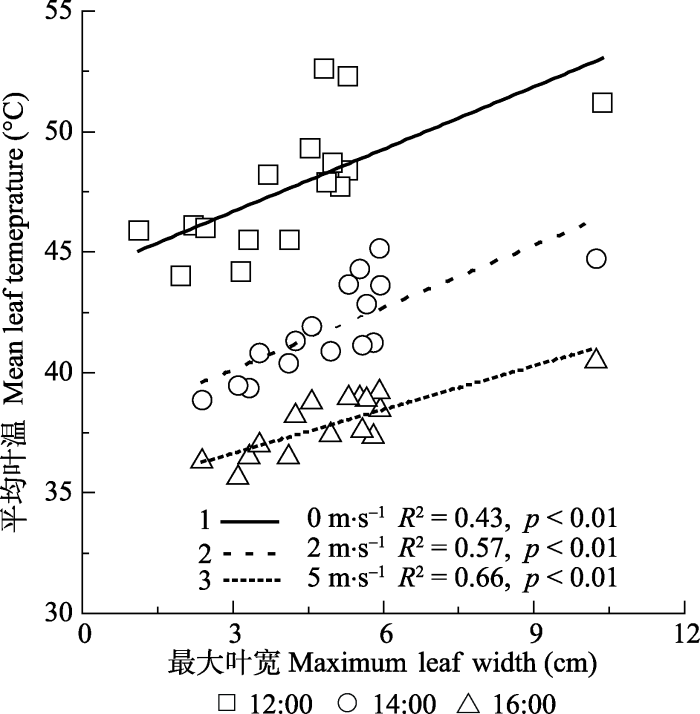

风洞测试结果显示, 模拟叶片形态变化对叶温的影响与真实叶片具有相同的趋势, 即随着叶片宽度减小(叶片变小), 植物叶片表面温度明显降低。不同的是, 模拟叶片形态与叶片表面温度的耦合关系更为密切(R2 = 0.43 - 0.66, p < 0.01)(图3), 但宽度变化对叶片温度的影响幅度降低。数据显示, 模拟叶片宽度每减少1 cm, 叶温降低0.60-0.86 ℃。另外, 从线性回归分析的斜率判断, 高风速环境下,模拟叶片温度对叶片宽度(或大小)变化的响应敏感性降低(图3)。在静风环境下(风速≈0 m·s-1), 气温在(32.2 ± 0.2) ℃时, 模拟叶片面积从60.3 cm2降低至1.8 cm2, 叶片平均温度降低8.6 ℃; 在高风速环境下(风速≈5 m·s-1), 气温在30.3 ℃时, 叶片面积从60.3 cm2降低至1.8 cm2, 叶片平均温度降低5.7 ℃。

图3

新窗口打开|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT

新窗口打开|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT图3不同风速下叶宽对模拟叶片温度的影响。

Fig. 3Empirical relationships between maximal leaf width and leaf temperature in a wind tunnel under different air flow velocity.

2.2 环境对叶片表面温度的影响

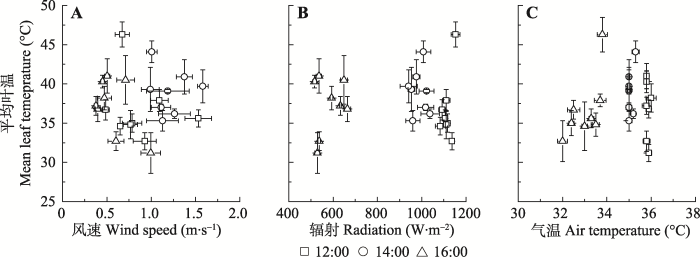

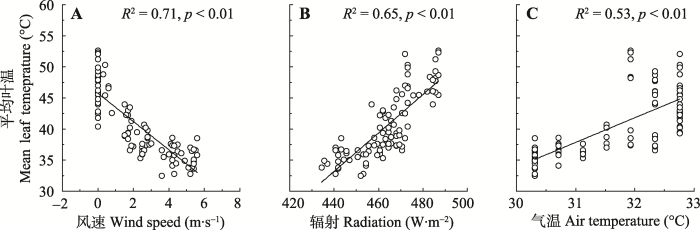

野外试验显示, 风速在0-2 m·s-1波动时, 无论在中午或下午, 风速变化对叶温影响均不明显。相同时段, 气温、辐射变化对叶片温度也没有显著影响(图4)。室内模拟实验显示, 在排除蒸腾影响的条件下, 风速、辐射及温度波动能够显著影响模拟叶片表面温度变化(R2 = 0.53-0.71, p < 0.01)(图5)。测试数据显示, 风速增加1 m·s-1, 模拟叶片温度降低约2.28 ℃; 辐射增加1 W·m-2, 模拟叶片温度升高约0.31 ℃; 气温增加1 ℃, 模拟叶片温度升高约3.97 ℃。图4

新窗口打开|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT

新窗口打开|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT图4风速、辐射、气温对叶片温度的影响(平均值±标准误差)。

Fig. 4Empirical relationships among wind speed, radiation, air temperature and leaf temperature (mean ± SE).

图5

新窗口打开|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT

新窗口打开|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT图5风速、辐射、气温对模拟叶片温度的影响。

Fig. 5Empirical relationships among wind speed, radiation, air temperature and leaf temperature.

2.3 叶片表面温度的分布特征

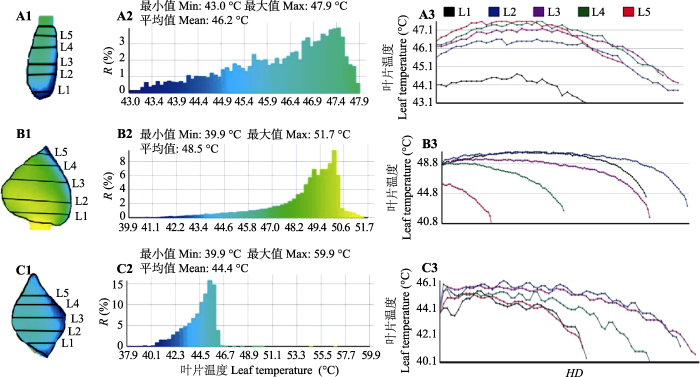

热成像图片(图1C)显示, 真实叶片和模拟叶片表面温度特征分布具有极大的相似性。分析数据显示, 流场方向是导致叶片表面温度渐变性分布的主要因子, 而叶片大小是影响叶片表面温度分布均匀性的主要因子。在低风速、叶片没有蒸腾或弱蒸腾条件下, 沿着空气流动方向, 迎风方向叶片温度最低, 而后叶片温度逐渐增加(图6)。从叶片表面分布均匀性看, 小叶片表面温度分布最为均匀, 叶片越窄(面积越小), 叶片温度分布区范围越小, 同时叶片表面平均温度也越低。另外, 从叶片表面温度剖面线来看, 小而窄的叶片温度较低且变化较快, 温度分布存在更为明显的边缘效应, 温度剖面线呈现单峰分布; 大而宽的叶片温度较高, 在背风面, 温度分布较为接近且变化缓慢, 在迎风面, 距离叶片边缘越近, 叶片温度降低越快(图6)。

图6

新窗口打开|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT

新窗口打开|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT图6单叶表面温度分布特征。A, 模拟叶片, 面积1.80 cm2, 气温32.3 ℃, 辐射478.6 W·m-2, 风速< 0.3 m·s-1。B, 模拟叶片, 面积23.7 cm2, 气温31.9 ℃, 辐射483.1 W· m-2, 风速< 0.3 m·s-1。C, 真实叶片, 面积5.4 cm2, 气温33.8 ℃, 辐射1β152.9 W·m-2, 风速0.7 m·s-1, 蒸腾1.9 mmol· m-2·s-1。A1、B1、C1是叶片热图像。A2、B2、C2是叶片表面温度分布特征。A3、B3、C3是叶片表面温度剖面线。HD, 距离下风向叶片边缘的水平距离; R, 不同叶片温度的分布区面积占叶片总面积的比例。L1-L5, 叶片上的位置。

Fig. 6Spatial changes in leaf temperature. A, Simulated leaf, leaf area 1.80 cm2, air temperature 32.3 °C, solar radiation 478.6 W·m-2, wind speed < 0.3 m·s-1. B, Simulated leaf, leaf area 23.7 cm2, air temperature 31.9 °C, solar radiation 483.1 W·m-2, wind speed < 0.3 m·s-1. C, Real leaf, leaf area 5.4 cm2, air temperature 33.8 °C, solar radiation 1β152.9 W·m-2, wind speed 0.7 m·s-1, transpiration rate 1.9 mmol·m-2·s-1. A1, B1, C1 were the thermal image of three leaf. A2, B2, C2 were temperature distributions on a leaf. A3, B3, C3 were temperature profile of a leaf. HD, horizontal distance from the leaf edge of the downwind direction; R, ratio of the distribution area of different leaf temperatures to the total leaf area. L1-L5, location on the leaves.

3 讨论和结论

自然环境下, 影响植物叶片温度的因子十分复杂。所有能够影响叶片能量捕获、存储、交换的因子都能够改变叶片表面温度(Ehleringer, 1980; Geller & Smith, 1982; Heckathorn & DeLucia, 1991; Nobel, 2005; Helliker & Richter, 2008; Lambers et al., 1998; Nicotra et al., 2008; Vogel, 2009)。这些因子包括影响叶片辐射吸收量的太阳辐射强度, 叶表颜色、质地、绒毛、叶角等因子; 影响叶片能量存储的叶片厚度、含水率、光合等因子; 以及影响能量交换速率的环境温度、叶片蒸腾速率、风速、叶片形态等因子。通常, 叶片能量存储对叶片温度的影响十分微小, 常可以忽略不计(Nobel, 2005; Liu et al., 2011)。蒸腾是调控叶温的重要因子, 但在干旱区却存在很大的局限性。当水分供给充足时, 蒸腾速率能够随温度(辐射)的增加而增加, 从而成为调控叶温的主导因子, 这一环境下叶形变化对叶温的影响能力相对较弱; 当水分供给不足或蒸腾微弱时, 高辐射(高温)对叶片的灼伤风险将增加, 这一环境下小叶片

植物因热传导、热对流能力强而具有更高的环境适应能力。在水分供给严重不足的环境下, 干旱区植物通常在早晨或上午气孔开度最大, 随后气孔导度快速降低, 蒸腾对叶温的调控能力也随之减弱或消失, 面对高辐射(高温)环境, 改变叶片形态, 增强热传导和热对流能力将成为植物调控叶温、适应环境的重要途径(Smith & Geller, 1980; Lambers et al., 1998; 李永华等, 2012; 刘明虎等, 2013)。

已有研究显示, 随降水的减少(温度增加)、水分有效性降低或辐射的增强, 植物单叶面积减小(Lambers et al., 1998; Bragg & Westoby, 2002; McDonald et al., 2003; Thuiller et al., 2004)。随着叶面积降低, 叶片将随之变窄(Rouphael et al., 2010)。本研究选择了3种生活型(乔灌草)叶片结构差异较大的8种植物进行了测试, 并与模拟叶片测试数据相互比对, 检查了形态变化对叶温的影响, 进一步确认了干旱区植物叶片变小对降低叶温的显著性与重要性。测定数据显示, 对于正常生长的干旱区植物, 蒸腾依然是调控叶温的主要途径, 但叶片形态变化对叶温调控的作用也十分显著(图2)。在排除叶片其他性状与生理活动的影响后, 基于相同的热传导和热对流原理(Nobel, 2005), 室内模拟实验结果进一步证实形态变化调控叶温的真实性(图2, 图3, 图6)。

另外, 我们也进一步发现, 与模拟叶片相比, 野外植物叶片变小对于降低叶温更为有效。根据空气动力学原理, 边界层阻力是控制物体表面与环境间物质、能量交换的主要因子(Nobel, 2005)。由于物体边界层阻力主要决定于形态和风速, 植物叶片变小有利于削弱自身的边界层阻力, 增强叶表与环境间的水热交换能力。换句话说, 在气孔导度相同或保持相同变率的情况下, 小叶片不仅可以增加叶片表面热传导和热对流速率, 而且也能够加快水分蒸腾速率, 提高热扩散速率。因此, 叶片宽度降低(叶片变小)过程中, 真实叶片温度降低速率高于模拟叶片。此外, 由于风速增加也能够降低物体边界层阻力, 增加叶表水热交换速率。因此, 在高风速环境下, 形态调控叶温的能力将被削弱(图3)。

除形态对叶片表面能量交换具有明显影响外, 外界环境, 如风速、气温、辐射等, 对于调控叶温变化也至关重要(Parkhurst & Loucks, 1972; Nobel, 2005)。本研究中, 室内模拟实验证实, 风速、气温、辐射变化对叶片表面温度具有显著调控能力, 但野外实验数据却显示风速、辐射和气温与叶温变化无关。对于这一结果, 我们初步推断有以下几个原因: 1)干旱区植物长期进化过程中, 主要通过蒸腾(气孔)和形态的可塑性主导叶片温度的调控, 从而降低了对外界环境的敏感性, 以此增加对高温、干旱环境的适应能力; 2)受微地貌、群落结构、测定位置等因素影响, 测试时叶片周边的风速、辐射、温度等因子与固定气象站测试数据不一致, 从而测定数据无法展示环境因子与叶片温度间的直接相关关系; 3)测试物种的叶片较小, 且测试过程中风速及波动范围较小, 无法辨识风速对叶片温度的影响。

本研究借鉴前人研究经验, 以模拟叶片替代真实叶片, 同时应用热成像仪替代温度探针(Vogel, 1968, 1970; Stokes et al., 2006; Vogel, 2009), 不仅实现了叶片温度的快速准确测定, 同时更为全面地展示了形态变化对叶片平均温度及叶片表面温度分布的显著影响。该方法便捷、快速、测定精度高、可重复, 适合植物叶片(包括其他组织)表面温度等相关的研究。但是, 由于叶温蒸腾的测定需要在LI-6400测定系统的封闭叶室内完成, 与自然环境相比较, 在高温、高辐射环境下, 叶室内温度、空气湿度等会发生较大变化, 并导致叶温与叶片蒸腾的剧烈波动。虽然我们应用热成像技术避免了温度测定中存在的误差, 但现有技术仍无法获取自然环境下的蒸腾数据, 从而造成我们测定的叶片温度与蒸腾数据不匹配。这一因素也能够导致本研究中蒸腾与叶片温度的耦合关系与真实情况之间存在一定的偏差。

参考文献 原文顺序

文献年度倒序

文中引用次数倒序

被引期刊影响因子

DOI:10.1046/j.1365-2435.2002.00661.xURL [本文引用: 1]

1. It has been suggested that leaf size may represent a foraging scale, with smaller-leaved species exploiting and requiring higher resource concentrations that are available in smaller patches. 2. Among 26 shrub species from a sclerophyll woodland community in New South Wales, Australia, species with smaller leaves tended to occur in better light environments, after controlling for height. The dark respiration rates of small-leaved species tended to exceed those of larger-leaved species. 3. However, the higher-light environments where smaller-leaved species tended to occur had a patch scale larger than whole plants. There would not have been any foraging-scale impediment to large-leaved species occupying these higher-light patches. An alternative explanation for small-leaved species being more successful in higher-light patches, in this vegetation with moderate shading, might be that they were less prone to leaf overheating. 4. Such relationships of leaf size to light across species at a given height may be important contributors to the wide spread of leaf sizes among species within a vegetation type, along with patterns down the light profile of the canopy, and effects associated with architecture and ramification strategy.

[本文引用: 1]

DOI:10.1007/BF00545668URLPMID:28311114 [本文引用: 1]

The temperature and water relations of the large-leafed, high-elevation species Frasera speciosa, Balsamorhiza sagittata, and Rumex densiflorus were evaluated in the Medicine Bow Mountains of southeast Wyoming (USA) to determine the influence of leaf size, orientation, and arrangement on transpiration. These species characteristically have low minimum stomatal resistances (< 60 s m-1) and high maximum transpiration rates (> 260 mg m-2s-1for F. speciosa). Field measurements of leaf and microclimatic parameters were incorporated into a computer simulation using standard energy balance equations which predicted leaf temperature ($T_{\text{leaf}}$) and transpiration for various leaf sizes. Whole-plant transpiration during a day was simulated using field measurements for plants with natural leaf sizes and compared to transpiration rates simulated for plants having identical, but hypothetically smaller (0.5 cm) leaves during a clear day and a typically cloudy day. Although clear-day transpiration for F. speciosa plants with natural size leaves was only 2.0% less per unit leaf area than that predicted for plants with much smaller leaves, daily transpiration of B. sagittata and R. densiflorus plants with natural leaf sizes was 16.1% and 21.1% less, respectively. The predicted influence of a larger leaf size on transpiration for the cloudy day was similar to clear-day results except that F. speciosa had much greater decreases in transpiration (12.7%). The different influences of leaf size on transpiration between the three species was primarily due to major differences in leaf absorptance to solar radiation, orientation, and arrangement which caused large differences in$T_{\text{leaf}}$. Also, simulated increases in leaf size above natural sizes measured in the field resulted in only small additional decreases in predicted transpiration, indicating a leaf size that was nearly optimal for reducing transpiration. These results are discussed in terms of the possible evolution of a larger leaf size in combination with specific leaf absorptances, orientations and arrangements which could act to reduce transpiration for species growing in short-season habitats where the requirement for rapid carbon fixation might necessitate low stomatal resistances.

[本文引用: 1]

DOI:10.1038/nature07031URLPMID:18548005 [本文引用: 2]

The oxygen isotope ratio (delta(18)O) of cellulose is thought to provide a record of ambient temperature and relative humidity during periods of carbon assimilation. Here we introduce a method to resolve tree-canopy leaf temperature with the use of delta(18)O of cellulose in 39 tree species. We show a remarkably constant leaf temperature of 21.4 +/- 2.2 degrees C across 50 degrees of latitude, from subtropical to boreal biomes. This means that when carbon assimilation is maximal, the physiological and morphological properties of tree branches serve to raise leaf temperature above air temperature to a much greater extent in more northern latitudes. A main assumption underlying the use of delta(18)O to reconstruct climate history is that the temperature and relative humidity of an actively photosynthesizing leaf are the same as those of the surrounding air. Our data are contrary to that assumption and show that plant physiological ecology must be considered when reconstructing climate through isotope analysis. Furthermore, our results may explain why climate has only a modest effect on leaf economic traits in general.

DOI:10.1016/S0065-2296(04)41003-9URL [本文引用: 1]

The applications of remote temperature sensing of plants by infrared thermography and infrared thermometry are reviewed and their advantages and disadvantages for various purposes discussed. The great majority of applications of thermography and of infrared thermometry depend on the sensitivity of leaf temperature to evaporation rate (and hence to stomatal aperture). In most applications, such as in the early or pre-symptomatic detection of disease or water deficits, what is actually being studied is the effect of the disease on stomatal behaviour or membrane permeability to water. Other applications of thermography in plant physiology include the study of thermogenesis as well as the characterisation of boundary layer transfer processes. Thermography is shown to be more than just a method for obtaining pretty pictures; it has particular advantages for the quantitative analysis of spatial and dynamic physiological information. Its capacity for large throughput has found application in screening approaches, such as in the selection of stomatal or hormonal mutants. The use of wet and dry reference surfaces for the enhancement of the power of thermal imaging approaches, especially in the field is reviewed, and the problems and potential solutions when applying thermography in the field and in the laboratory discussed.

DOI:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2004.01317.xURLPMID:15760364 [本文引用: 1]

61 CO2 fixation in a leaf is determined by biochemical and physical processes within the boundaries set by leaf structure. Traditionally determined temperature dependencies of biochemical processes include physical processes related to CO2 exchange that result in inaccurate estimates of parameter values. 61 A realistic three-dimensional model of a birch (Betula pendula) leaf was used to distinguish between the physical and biochemical processes affecting the temperature dependence of CO2 exchange, to determine new chloroplastic temperature dependencies for Vc( max) and J max based on experiments, and to analyse mesophyll diffusion in detail. 61 The constraint created by dissolution of CO2 at cell surfaces substantially decreased the CO2 flux and its concentration inside chloroplasts, especially at high temperatures. Consequently, newly determined chloroplastic Vc( max) and J max were more temperature dependent than originally. The role of carbonic anhydrase in mesophyll diffusion appeared to be minor under representative mid-day nonwater-limited conditions. 61 Leaf structure and physical processes significantly affect the apparent temperature dependence of CO2 exchange, especially at optimal high temperatures when the photosynthetic sink is strong. The influence of three-dimensional leaf structure on the light environment inside a leaf is marked and affects the local choice between J max and Vc( max)-limited assimilation rates.

DOI:10.2307/1931367URL [本文引用: 1]

Experiments were carried out to ascertain the depen-dence of transpiration upon the temperature gradient between air and leaf. Varying temperatures were induced by varying the position of adjacent leaves between the horizontal and vertical. Seven species of maquis plants were used. It is shown that temperature increments of the leaves on a clear sunny day are capable of increasing transpiration...

[本文引用: 5]

DOI:10.3724/SP.J.1258.2012.00088URL [本文引用: 1]

Leaf morphology is closely related to the specific environment and provides the most useful characteristics to understand plant response and adaptation strategy to environmental change. Leaf morphology plasticity is obviously related to the temporal and spatial variation of environmental variables, which are useful to plants to enhance their ability to survive. Consequently, for many years, studies on plant physiology, plant ecology and physiological ecology focused on leaf morphology. We establish a simple category of leaf morphology classification. Simultaneously, based on the principle of material and energy balances, we systematically review the relationships among environment, leaf morphology and energy balances (or material changes), and emphasize that leaf morphology responded or adapted to lower water availability and higher radiation (or temperature) in arid ecosystems. In conclusion, we submit and discuss existing problems in leaf morphology based on the weaknesses of previous studies.

DOI:10.3724/SP.J.1258.2012.00088URL [本文引用: 1]

Leaf morphology is closely related to the specific environment and provides the most useful characteristics to understand plant response and adaptation strategy to environmental change. Leaf morphology plasticity is obviously related to the temporal and spatial variation of environmental variables, which are useful to plants to enhance their ability to survive. Consequently, for many years, studies on plant physiology, plant ecology and physiological ecology focused on leaf morphology. We establish a simple category of leaf morphology classification. Simultaneously, based on the principle of material and energy balances, we systematically review the relationships among environment, leaf morphology and energy balances (or material changes), and emphasize that leaf morphology responded or adapted to lower water availability and higher radiation (or temperature) in arid ecosystems. In conclusion, we submit and discuss existing problems in leaf morphology based on the weaknesses of previous studies.

DOI:10.1016/j.envexpbot.2010.11.010URL [本文引用: 2]

Leaf temperature has been shown to vary when plants are subjected to water stress conditions. Recent advances in infrared thermography have increased the probability of recording drought tolerant responses more accurately. The aims of this study were to identify the effects of drought on leaf temperature using infrared thermography. Furthermore, the genomic regions responsible for the expression of leaf temperature variation in maize seedlings (Zea mays L.) were explored. The maize inbred lines Zong3 and 87-1 were evaluated using infrared thermography and exhibited notable differences in leaf temperature response to water stress. Correlation analysis indicated that leaf temperature response to water stress played an integral role in maize biomass accumulation. Additionally, a mapping population of 187 recombinant inbred lines (RILs) derived from a cross between Zong3 and 87-1 was constructed to identify quantitative trait loci (QTL) responsible for physiological traits associated with seedling water stress. Leaf temperature differences (LTD) and the drought tolerance index (DTI) of shoot fresh weight (SFW) and shoot dry weight (SDW) were the traits evaluated for QTL analysis in maize seedlings. A total of nine QTL were detected by composite interval mapping (CIM) for the three traits (LTD, RSFW and RSDW). Two co-locations responsible for both RSFW and RSDW were detected on chromosomes 1 and 2, respectively, which showed common signs with their trait correlations. Another co-location was detected on chromosome 9 between LTD and shoot biomass, which provided genetic evidence that leaf temperature affects biomass accumulation. Additionally, the utility of a thermography system for drought tolerance breeding in maize was discussed.

DOI:10.3724/SP.J.1258.2013.00045URL [本文引用: 1]

利用热及物质交换原理,并结合前人研究成果,在单叶尺度上建立了简单的叶温和水气蒸腾模型。模型通过预设值驱动,预设值参照干旱区环境及植物叶片特征设置。模拟结果显示:随气孔阻力的增加,叶片蒸腾速率降低,叶温升高;同一环境下,具有低辐射吸收率的叶片蒸腾速率和叶温更低,并且气孔阻力越大,这种差异越明显。另外,叶片宽度及风速是影响叶片蒸腾及叶温的重要因子。干旱地区植物生长季节,风速小于0.1m·s^-1、气孔阻力接近1000s.m^-1时,降低叶片宽度不仅有利于降低叶片温度,而且能够降低叶片蒸腾速率,从而实现保持水分,增强植物适应高温、干旱的能力。

DOI:10.3724/SP.J.1258.2013.00045URL [本文引用: 1]

利用热及物质交换原理,并结合前人研究成果,在单叶尺度上建立了简单的叶温和水气蒸腾模型。模型通过预设值驱动,预设值参照干旱区环境及植物叶片特征设置。模拟结果显示:随气孔阻力的增加,叶片蒸腾速率降低,叶温升高;同一环境下,具有低辐射吸收率的叶片蒸腾速率和叶温更低,并且气孔阻力越大,这种差异越明显。另外,叶片宽度及风速是影响叶片蒸腾及叶温的重要因子。干旱地区植物生长季节,风速小于0.1m·s^-1、气孔阻力接近1000s.m^-1时,降低叶片宽度不仅有利于降低叶片温度,而且能够降低叶片蒸腾速率,从而实现保持水分,增强植物适应高温、干旱的能力。

DOI:10.1046/j.1365-2435.2003.00698.xURL [本文引用: 1]

1. Ecologists have long recognized that plants occurring in areas of low rainfall or soil nutrients tend to have smaller leaves than those in more favourable regions. 2. Working with a large data set (690 species at 47 sites spread widely through southeast Australia) for which this reduction has been described previously, we investigated the morphology of leaf size reduction, asking whether any patterns observed were consistent across evolutionary lineages or between environmental gradients. 3. Leaf length, width and surface areas were measured; leaf traits such as pubescence or lobing were also scored qualitatively. There was no correlation between soil phosphorus and rainfall across sites. Further, there was no evidence that pubescence, lobing or other traits assessed served as alternatives to reduction of leaf size at the low ends of either environmental gradient. 4. Leaf size reduction occurred through many combinations of change in leaf width and length, even within lineages. Thus consistent patterns in the method of leaf size reduction were not found, although broad similarities between rainfall and soil P gradients were apparent.

DOI:10.1139/x91-224URL [本文引用: 1]

ABSTRACT Rates of net photosynthesis, dark respiration, and photorespiration of six half-sib families of black locust (Robiniapseudoacacia L.) were measured at leaf temperatures ranging from 10 to 40 C. Rates of dark respiration increased with increasing leaf temperature in all families and reached as high as 67% of gross photosynthesis at 40 C in one family. Dark respiration of foliage accounted for 12.5 to 59% of the reduction in net photosynthesis at temperatures higher than those optimum for net photosynthesis. Rates of photorespiration peaked at 10 to 20 C, exhibiting the same pattern as net photosynthesis, and did not contribute to the decline in net photosynthesis at high temperatures. The families with high rates of net photosynthesis also had high rates of photorespiration. Rates of dark respiration were significantly different among the families, and the slow-growing families had the highest rates of dark respiration. A significant interaction between half-sib families and leaf temperatures was noted for dark respiration. The data indicated the possibility of improving the growth of black locust by selection and breeding for large leaf area, high rates of net photosynthesis and low rates of dark respiration.

DOI:10.1007/s00442-007-0865-1URLPMID:17943318 [本文引用: 1]

The thermal response of gas exchange varies among plant species and with growth conditions. Plants from hot dry climates generally reach maximal photosynthetic rates at higher temperatures than species from temperate climates. Likewise, species in these environments are predicted to have small leaves with more-dissected shapes. We compared eight species of Pelargonium (Geraniaceae) selected as phylogenetically independent contrasts on leaf shape to determine whether: (1) the species showed plasticity in thermal response of gas exchange when grown under different water and temperature regimes, (2) there were differences among more-and less-dissected leafed species in trait means or plasticity, and (3) whether climatic variables were correlated with the responses. We found that a higher growth temperature led to higher optimal photosynthetic temperatures, at a cost to photosynthetic capacity. Optimal temperatures for photosynthesis were greater than the highest growth temperature regime. Stomatal conductance responded to growth water regime but not growth temperature, whereas transpiration increased and water use efficiency (WUE) decreased at the higher growth temperature. Strikingly, species with more-dissected leaves had higher rates of carbon gain and water loss for a given growth condition than those with less-dissected leaves. Species from lower latitudes and lower rainfall tended to have higher photosynthetic maxima and conductance, but leaf dissection did not correlate with climatic variables. Our results suggest that the combination of dissected leaves, higher photosynthetic rates, and relatively low WUE may have evolved as a strategy to optimize water delivery and carbon gain during short-lived periods of high soil moisture. Higher thermal optima, in conjunction with leaf dissection, may reflect selection pressure to protect photosynthetic machinery against excessive leaf temperatures when stomata close in response to water stress.

[本文引用: 9]

DOI:10.2307/2258359URL [本文引用: 1]

The principle of optimal design (Rosen 1967) can be stated as follows. `Natural selection leads to organisms having a combination of form and function optimal for growth and reproduction in the environments in which they live.' This principle provides a general framework for the study of adaptation in plants and animals. The efficiency of water use by plants (Slatyer 1964) can be defined as grams of carbon dioxide assimilated per gram of water lost. Leaf temperatures, transpiration rates, and water-use efficiencies can be calculated for single leaves using well-established principles of heat and mass transfer. The calculations are complex, however, depending on seven independent variables such as air temperature, humidity and stomatal resistance. The calculations can be treated as artificial data in a 2Nfactorial design experiment. This technique is used to compare the sensitivity of the system response variables to changes in the independent variables, and to their interactions. The assumption is made (as a first approximation) that the optimal leaf size in a given environment is the size yielding the maximum water-use efficiency. This very simple assumption leads to predictions of trends in leaf size which agree well with the observed trends in diverse regions (tropical rainforest, desert, arctic, etc.). Specifically, the model predicts that large leaves should be selected for only in warm or hot environments with low radiation (e.g. forest floors in temperate and tropical regions). There are some plant forms and microhabitats for which observed leaf sizes disagree with the predictions of the simple model. Refinements are thus proposed to include more factors in the model, such as the temperature dependence of net photosynthesis. It is shown that these refinements explain much of the lack of agreement of the simpler model. One of the main roles of mathematical models in science is `to pose sharp questions' (Kac 1969). The present model suggests several speculative propositions, some of which would be difficult to prove experimentally. Others, whether true or not, can serve as a theoretical framework against which to compare experimental results. The propositions are as follows. (1) Every environment tends to select for leaf sizes increasing the efficiency of water utilization, that is, the ratio of CO2uptake to water loss. (2) Herbs are physiologically different from woody plants, in such a way that water-use efficiency has been more important in the evolution of the latter. (3) The stomatal resistance of a given leaf varies diurnally in such a way that the water-use efficiency of that leaf tends to be a maximum. (4) The larger the photosynthesizing surface of a desert succulent, the more likely it is to exhibit acid metabolism, with stomata open at night and closed during the day. (5) In arctic and alpine regions, the plant species whose carbohydrate metabolism is most severely limited by low temperatures are most likely to evolve a cushion form of growth. In addition to providing these testable hypotheses, the results of the model may be useful in other ways. For example, they should help plant breeders to alter water-use efficiencies, and they could help palaeobotanists interpret past climates from fossil floras.

DOI:10.1046/j.1365-3040.2001.00712.xURL [本文引用: 1]

Abstract In order to study convective heat transfer of small leaves, the steady-state and transient heat flux of small leaf-shaped model structures (area of one side = 1730mm 2 ) were studied under zero and low (= 100mm s 611 ) wind velocities by using a computer simulation method. The results show that: (1) distinct temperature gradients of several degrees develop over the surface of the model objects during free and mixed convection; and (2) the shape of the objects and onset of low wind velocities has a considerable effect on the resulting temperature pattern and on the time constant τ . Small leaves can thus show a temperature distribution which is far from uniform under zero and low wind conditions. The approach leads, however, to higher leaf temperatures than would be attained by ‘real’ leaves under identical conditions, because heat transfer by transpiration is neglected. The results demonstrate the fundamental importance of a completely controlled environment when measuring heat dissipation by free convection. As slight air breezes alter the temperature of leaves significantly, the existence of purely free convection appears to be questionable in the case of outdoor conditions. Contrary to the prognoses yielded by standard approximations, no quantitative effect of buoyancy on heat transfer under the considered conditions could be detected for small-sized leaf shapes.

DOI:10.1007/s11099-010-0003-xURL [本文引用: 1]

Accurate and nondestructive methods to determine individual leaf areas of plants are a useful tool in physiological and agronomic research. Determining the individual leaf area (LA) of rose ( Rosa hybrida L.) involves measurements of leaf parameters such as length (L) and width (W), or some combinations of these parameters. Two-year investigation was carried out during 2007 (on thirteen cultivars) and 2008 (on one cultivar) under greenhouse conditions, respectively, to test whether a model could be developed to estimate LA of rose across cultivars. Regression analysis of LA vs . L and W revealed several models that could be used for estimating the area of individual rose leaves. A linear model having LW as the independent variable provided the most accurate estimate (highest r 2 , smallest MSE, and the smallest PRESS) of LA in rose. Validation of the model having LW of leaves measured in the 2008 experiment coming from other cultivars of rose showed that the correlation between calculated and measured rose LA was very high. Therefore, this model can estimate accurately and in large quantities the LA of rose plants in many experimental comparisons without the use of any expensive instruments.

DOI:10.1111/j.1469-8137.1993.tb03898.xURL [本文引用: 1]

Abstract Studies of heat and mass exchange between leaves and their local environment are central to our understanding of plant-atmosphere interactions. The transfer across aerodynamic leaf boundary layers is generally described by non-dimensional expressions which reflect largely empirical adaptations of engineering models derived for flat plates. This paper reviews studies on leaves, and leaf models with varying degrees of abstraction, in free and forced convection. It discusses implecations of finding for leaf morphology as it affects – and is affected by – the local microclimate. Predictions of transfer from many leaves in plant communities are complicated by physical and physiological feedback mechanisms between leaves and their environment. Some common approaches, and the current challenge of integrating leaf-atmosphere interactions into models of global relevance, are also briefly addressed.

DOI:10.1007/BF00346257URL [本文引用: 4]

The influence of vari tions in the boundary air layer thickness on transpiration due to changes in leaf dimension or wind speed was evaluated at a given stomatal resistance (rs) for various combinations of air temperature (Ta) and total absorbed solar energy expressed as a fraction of full sunlight ($S_{\text{ffs}}$). Predicted transpiration was found to either increase or decrease for increases in leaf size depending on specific combinations of Ta,$S_{\text{ffs}}$, and rs. Major reductions in simulated transpiration with increasing leaf size occurred for shaded, highly reflective, or specially oriented leaves ($S_{\text{ffs}}$= 0.1) at relatively high Tawhen rswas below a critical value of near 500 s m-1. Increases in$S_{\text{ffs}}$and decreases in Talowered this critical resistance to below 50 s m-1for$S_{\text{ffs}}$= 0.7 and Ta= 20C. In contrast, when rswas above this critical value, an increase in leaf dimension (or less wind) resulted in increases in transpiration, especially at high Taand$S_{\text{ffs}}$. For several combinations of Ta,$S_{\text{ffs}}$, and rs, transpiration was minimal for a specific leaf size. These theoretical results were compared to field measurements on common desert, alpine, and subalpine plants to evaluate the possible interactions of leaf and environmental parameters that may serve to reduce transpiration in xeric habitats.

DOI:10.1016/j.agrformet.2006.05.011URL [本文引用: 3]

A new method of constructing light, flexible and more realistic replica leaves for continuous determination of leaf boundary layer conductance to heat transfer ( g b h) was developed and tested in a mature oak ( Quercus robur L.) and sycamore ( Acer pseudoplatanus L.) tree canopy. The replicas were used to determine the difference between oak and sycamore leaf g b h in exposed sites in the upper canopy, the relationship of g b h with wind speed, the seasonal changes in g b h in the canopy as leaf cover developed, and values for Ω, the decoupling coefficient. The replicas showed similar gradients in temperature at their margins to those in real leaves. When exposed, the g b h of the larger sycamore leaves was 66% of that of oak leaves under the same conditions. Linear relationships were found with g b h and wind speed across the measured range of 0.3–3.5 m s 611, and flow in the replica boundary layers was laminar in all conditions. The leafless canopy produced a substantial sheltering effect, reducing g b h by 12–28% in light winds. Sycamore replicas in the leafed canopy showed a 19–29% lower g b h at a given external wind speed than when outside, but there was little difference between ‘sun’ and ‘shade’ position shoots, because of the density of the shoots, and the close branching pattern. In contrast, in oak g b h at a given wind speed was 15–21% lower for ‘sun’ leaves than that for replicas outside the canopy, with a larger reduction (approximately 28%) in denser ‘shade’ sites. Although wind speed in the canopy was often low, leaves of both species were usually well coupled to the canopy airstream ( Ω < 0.3). Sun leaves were substantially less well coupled than shade leaves, despite the lower shelter effect, because of their higher stomatal conductance values. In the lightest winds (<0.5 m s 611) and with high stomatal conductance, coupling may on many occasions be poor for sun leaves, particularly for the larger sycamore leaves.

[本文引用: 1]

DOI:10.2307/1934517URL [本文引用: 2]

Temperatures of radiantly heated sun and shade leaves of white oak (Quercus alba L.) were measured in a low-speed wind tunnel. In either still air or a gentle updraft the difference between ambient and leaf temperature is about 20% less for the sum leaves than for the shade leaves. Consequently the former are more effective heat dissipaters.

DOI:10.1093/jxb/21.1.91URL [本文引用: 1]

Circular, abstractly lobed, and leaf-shaped flat copper plates were heated in a very low-speed wind tunnel. Surface temperature distributions of the plates were matched to those of real leaves. With the centres of the plates 15 C above ambient temperature, their heat dissipation was measured at wind velocities of < 1, 10, and 30 cm s-1 from below and laterally with horizontal and vertical plate orientations. Even very slight forced-air movements markedly increased heat dissipation in this range of mixed free and forced convection. Lobed plates were more effective dissipators than circles, with the greatest differences occurring where flow was normal to the plate. Circular plates dissipated about one-fourth more heat when vertical than when horizontal in still air (free convection). By contrast, dissipation was essentially independent of orientation for extensively lobed models. Under some circumstances, maximum dissipation occurred with lobed plates oblique to a forced air stream. Physical explanations and biological implications of these results are discussed.

DOI:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.02854.xURLPMID:19413689 [本文引用: 5]

Abstract Climatic extremes can be as significant as averages in setting the conditions for successful organismal function and in determining the distribution of different forms. For lightweight, flexible structures such as leaves, even extremes lasting a few seconds can matter. The present review considers two extreme situations that may pose existential risks. Broad leaves heat rapidly when ambient air flows drop below c. 0.5 m s(-1). Devices implicated in minimizing heating include: reduction in size, lobing, and adjustments of orientation to improve convective cooling; low near-infrared absorptivity; and thickening for short-term heat storage. Different features become relevant when storm gusts threaten to tear leaves and uproot trees with leaf-level winds of 20 m s(-1) or more. Both individual leaves and clusters may curl into low-drag, stable cones and cylinders, facilitated by particular blade shapes, petioles that twist readily, and sufficient low-speed instability to initiate reconfiguration. While such factors may have implications in many areas, remarkably little relevant experimental work has addressed them.

DOI:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.33.010802.150452URL [本文引用: 1]

DOI:10.1111/nph.12321URLPMID:23718199 [本文引用: 1]

Tree species growing along the forest090009grassland ecotone are near the moisture limit of their range. Small increases in temperature can increase vapor pressure deficit (VPD) which may increase tree water use and potentially hasten mortality during severe drought.We tested a 40% increase in VPD due to an increase in growing temperature from 30 to 3300°C (constant dewpoint 2100°C) on seedlings of 10 tree species common to the forest090009grassland ecotone in the southern Great Plains, USA.Measurement at 33 vs 3000°C during reciprocal leaf gas exchange measurements, that is, measurement of all seedlings at both growing temperatures, increased transpiration for seedlings grown at 3000°C by 40% and 20% for seedlings grown at 3300°C. Higher initial transpiration of seedlings in the 3300°C growing temperature treatment resulted in more negative xylem water potentials and fewer days until transpiration decreased after watering was withheld. The seedlings grown at 3300°C died 13% (average 2 d) sooner than seedlings grown at 3000°C during terminal drought.If temperature and severity of droughts increase in the future, the forest090009grassland ecotone could shift because low seedling survival rate may not sufficiently support forest regeneration and migration.

[本文引用: 2]

Leaf size and foraging for light in a sclerophyll woodland

1

2002

... id="C27">已有研究显示, 随降水的减少(温度增加)、水分有效性降低或辐射的增强, 植物单叶面积减小(

1

1980

... id="C24">自然环境下, 影响植物叶片温度的因子十分复杂.所有能够影响叶片能量捕获、存储、交换的因子都能够改变叶片表面温度(

Influence of leaf size, orientation, and arrangement on temperature and transpiration in three high-elevation, large-leafed herbs

1

1982

... id="C24">自然环境下, 影响植物叶片温度的因子十分复杂.所有能够影响叶片能量捕获、存储、交换的因子都能够改变叶片表面温度(

Effect of leaf rolling on gas exchange and leaf temperature of

1

1991

... id="C24">自然环境下, 影响植物叶片温度的因子十分复杂.所有能够影响叶片能量捕获、存储、交换的因子都能够改变叶片表面温度(

Subtropical to boreal convergence of tree-leaf temperatures

2

2008

... id="C4">叶片温度作为影响叶片光合、呼吸(

... id="C24">自然环境下, 影响植物叶片温度的因子十分复杂.所有能够影响叶片能量捕获、存储、交换的因子都能够改变叶片表面温度(

Application of thermal imaging and infrared sensing in plant physiology and ecophysiology

1

2005

... id="C8">近年来, 红外热成像测温技术的逐步成熟(

Temperature dependence of leaf-level CO2 fixation: Revising biochemical coefficients through analysis of leaf three- dimensional structure

1

2005

... id="C4">叶片温度作为影响叶片光合、呼吸(

The effect of leaf temperature on transpiration

1

1950

... id="C4">叶片温度作为影响叶片光合、呼吸(

Plant Physiological Ecology. Springer-Verlag

5

1998

... id="C4">叶片温度作为影响叶片光合、呼吸(

... id="C6">叶片形态变化对能量(及物质)流动速率的影响决定于叶片表面边界层阻力(

... id="C24">自然环境下, 影响植物叶片温度的因子十分复杂.所有能够影响叶片能量捕获、存储、交换的因子都能够改变叶片表面温度(

... id="C26">植物因热传导、热对流能力强而具有更高的环境适应能力.在水分供给严重不足的环境下, 干旱区植物通常在早晨或上午气孔开度最大, 随后气孔导度快速降低, 蒸腾对叶温的调控能力也随之减弱或消失, 面对高辐射(高温)环境, 改变叶片形态, 增强热传导和热对流能力将成为植物调控叶温、适应环境的重要途径(

... id="C27">已有研究显示, 随降水的减少(温度增加)、水分有效性降低或辐射的增强, 植物单叶面积减小(

干旱区叶片形态特征与植物响应和适应的关系

1

2012

... id="C26">植物因热传导、热对流能力强而具有更高的环境适应能力.在水分供给严重不足的环境下, 干旱区植物通常在早晨或上午气孔开度最大, 随后气孔导度快速降低, 蒸腾对叶温的调控能力也随之减弱或消失, 面对高辐射(高温)环境, 改变叶片形态, 增强热传导和热对流能力将成为植物调控叶温、适应环境的重要途径(

干旱区叶片形态特征与植物响应和适应的关系

1

2012

... id="C26">植物因热传导、热对流能力强而具有更高的环境适应能力.在水分供给严重不足的环境下, 干旱区植物通常在早晨或上午气孔开度最大, 随后气孔导度快速降低, 蒸腾对叶温的调控能力也随之减弱或消失, 面对高辐射(高温)环境, 改变叶片形态, 增强热传导和热对流能力将成为植物调控叶温、适应环境的重要途径(

Maize leaf temperature responses to drought: Thermal imaging and quantitative trait loci (QTL) mapping

2

2011

... id="C4">叶片温度作为影响叶片光合、呼吸(

... id="C25">通常, 叶片能量存储对叶片温度的影响十分微小, 常可以忽略不计(

干旱区植物叶片大小对叶表面蒸腾及叶温的影响

1

2013

... id="C26">植物因热传导、热对流能力强而具有更高的环境适应能力.在水分供给严重不足的环境下, 干旱区植物通常在早晨或上午气孔开度最大, 随后气孔导度快速降低, 蒸腾对叶温的调控能力也随之减弱或消失, 面对高辐射(高温)环境, 改变叶片形态, 增强热传导和热对流能力将成为植物调控叶温、适应环境的重要途径(

干旱区植物叶片大小对叶表面蒸腾及叶温的影响

1

2013

... id="C26">植物因热传导、热对流能力强而具有更高的环境适应能力.在水分供给严重不足的环境下, 干旱区植物通常在早晨或上午气孔开度最大, 随后气孔导度快速降低, 蒸腾对叶温的调控能力也随之减弱或消失, 面对高辐射(高温)环境, 改变叶片形态, 增强热传导和热对流能力将成为植物调控叶温、适应环境的重要途径(

Leaf-size divergence along rainfall and soil-nutrient gradients: Is the method of size reduction common among clades?

1

2003

... id="C27">已有研究显示, 随降水的减少(温度增加)、水分有效性降低或辐射的增强, 植物单叶面积减小(

Leaf temperature effects on net photosynthesis, dark respiration, and photorespiration of seedlings of black locust families with contrasting growth rates

1

1991

... id="C4">叶片温度作为影响叶片光合、呼吸(

Leaf shape linked to photosynthetic rates and temperature optima in South African Pelargonium species.

1

2008

... id="C24">自然环境下, 影响植物叶片温度的因子十分复杂.所有能够影响叶片能量捕获、存储、交换的因子都能够改变叶片表面温度(

Physicochemical and Environmental Plant Physiology. 4th edn. Elsevier, Amsterdam, the

9

2005

... id="C4">叶片温度作为影响叶片光合、呼吸(

... id="C5">等研究手段, 探索研究了叶片表面温度变化与环境、蒸发、叶片形态的关系.研究结果表明, 叶片温度除受环境因子和蒸腾因素影响外, 也与叶片形态密切相关(

... id="C6">叶片形态变化对能量(及物质)流动速率的影响决定于叶片表面边界层阻力(

... ).植物叶面积减小(叶片宽度降低)有利于降低叶片边界层阻力, 增加叶片表面能量与环境的交换速率(

... id="C24">自然环境下, 影响植物叶片温度的因子十分复杂.所有能够影响叶片能量捕获、存储、交换的因子都能够改变叶片表面温度(

... id="C25">通常, 叶片能量存储对叶片温度的影响十分微小, 常可以忽略不计(

... id="C27">已有研究显示, 随降水的减少(温度增加)、水分有效性降低或辐射的增强, 植物单叶面积减小(

... id="C28">另外, 我们也进一步发现, 与模拟叶片相比, 野外植物叶片变小对于降低叶温更为有效.根据空气动力学原理, 边界层阻力是控制物体表面与环境间物质、能量交换的主要因子(

... id="C29">除形态对叶片表面能量交换具有明显影响外, 外界环境, 如风速、气温、辐射等, 对于调控叶温变化也至关重要(

Optimal leaf size in relation to environment

1

1972

... id="C29">除形态对叶片表面能量交换具有明显影响外, 外界环境, 如风速、气温、辐射等, 对于调控叶温变化也至关重要(

Computer-based analysis of steady- state and transient heat transfer of small-sized leaves by free and mixed convection

1

2001

... id="C4">叶片温度作为影响叶片光合、呼吸(

Modeling individual leaf area of rose (Rosa hybrida L.) based on leaf length and width measurement.

1

2010

... id="C27">已有研究显示, 随降水的减少(温度增加)、水分有效性降低或辐射的增强, 植物单叶面积减小(

Tansley review No. 59. Leaf boundary layers

1

1993

... id="C6">叶片形态变化对能量(及物质)流动速率的影响决定于叶片表面边界层阻力(

Leaf and environmental parameters influencing transpiration: Theory and field measurements

4

1980

... id="C4">叶片温度作为影响叶片光合、呼吸(

... id="C5">等研究手段, 探索研究了叶片表面温度变化与环境、蒸发、叶片形态的关系.研究结果表明, 叶片温度除受环境因子和蒸腾因素影响外, 也与叶片形态密切相关(

... id="C6">叶片形态变化对能量(及物质)流动速率的影响决定于叶片表面边界层阻力(

... id="C26">植物因热传导、热对流能力强而具有更高的环境适应能力.在水分供给严重不足的环境下, 干旱区植物通常在早晨或上午气孔开度最大, 随后气孔导度快速降低, 蒸腾对叶温的调控能力也随之减弱或消失, 面对高辐射(高温)环境, 改变叶片形态, 增强热传导和热对流能力将成为植物调控叶温、适应环境的重要途径(

Boundary layer conductance for contrasting leaf shapes in a deciduous broadleaved forest canopy

3

2006

... id="C4">叶片温度作为影响叶片光合、呼吸(

... id="C8">近年来, 红外热成像测温技术的逐步成熟(

... id="C30">本研究借鉴前人研究经验, 以模拟叶片替代真实叶片, 同时应用热成像仪替代温度探针(

Relating plant traits and species distributions along bioclimatic gradients for 88

1

2004

... id="C27">已有研究显示, 随降水的减少(温度增加)、水分有效性降低或辐射的增强, 植物单叶面积减小(

“Sun leaves” and “shade leaves”: Differences in convective heat dissipation

2

1968

... id="C7">如何在复杂的生物物理过程中准确测定叶片表面温度一直是研究的难点.以往研究中, 常以热电阻或热电偶测定叶片温度(

... id="C30">本研究借鉴前人研究经验, 以模拟叶片替代真实叶片, 同时应用热成像仪替代温度探针(

Convective cooling at low airspeeds and the shapes of broad leaves

1

1970

... id="C30">本研究借鉴前人研究经验, 以模拟叶片替代真实叶片, 同时应用热成像仪替代温度探针(

Leaves in the lowest and highest winds: Temperature, force and shape

5

2009

... id="C4">叶片温度作为影响叶片光合、呼吸(

... id="C5">等研究手段, 探索研究了叶片表面温度变化与环境、蒸发、叶片形态的关系.研究结果表明, 叶片温度除受环境因子和蒸腾因素影响外, 也与叶片形态密切相关(

... id="C7">如何在复杂的生物物理过程中准确测定叶片表面温度一直是研究的难点.以往研究中, 常以热电阻或热电偶测定叶片温度(

... id="C24">自然环境下, 影响植物叶片温度的因子十分复杂.所有能够影响叶片能量捕获、存储、交换的因子都能够改变叶片表面温度(

... id="C30">本研究借鉴前人研究经验, 以模拟叶片替代真实叶片, 同时应用热成像仪替代温度探针(

Plant ecological strategies: Some leading dimensions of variation between species

1

2002

... id="C6">叶片形态变化对能量(及物质)流动速率的影响决定于叶片表面边界层阻力(

Increased vapor pressure deficit due to higher temperature leads to greater transpiration and faster mortality during drought for tree seedlings common to the forest-grassland ecotone

1

2013

... id="C4">叶片温度作为影响叶片光合、呼吸(

Electron transport is the functional limitation of photosynthesis in field-grown Pima cotton plants at high temperature

2

2004

... id="C4">叶片温度作为影响叶片光合、呼吸(

... id="C6">叶片形态变化对能量(及物质)流动速率的影响决定于叶片表面边界层阻力(

Copyright © 2021 版权所有 《植物生态学报》编辑部

地址: 北京香山南辛村20号, 邮编: 100093

Tel.: 010-62836134, 62836138; Fax: 010-82599431; E-mail: apes@ibcas.ac.cn, cjpe@ibcas.ac.cn

备案号: 京ICP备16067583号-19