,1,*1

,1,*1 2

Experimental warming changed plants’ phenological sequences of two dominant species in an alpine meadow, western of Sichuan

ZHANG Li1,2, WANG Gen-Xu1, RAN Fei1, PENG A-Hui1,2, XIAO Yao1,2, YANG Yang1, YANG Yan ,1,*1

,1,*1 and 2

通讯作者:

| 基金资助: |

Online:2018-01-20

| Fund supported: |

摘要

关键词:

Abstract

Keywords:

PDF (1169KB)元数据多维度评价相关文章导出EndNote|Ris|Bibtex收藏本文

本文引用格式

张莉, 王根绪, 冉飞, 彭阿辉, 肖瑶, 杨阳, 杨燕. 模拟增温改变川西高山草甸优势植物繁殖物候序列特征. 植物生态学报[J], 2018, 42(1): 20-27 doi:10.17521/cjpe.2017.0133

ZHANG Li.

联合国政府间气候变化专门委员会(IPCC)第五次评估报告显示, 1901-2012年, 地球表面平均温度上升了0.89 ℃ (IPCC, 2013)。中国地表气温也发生了显著的变化, 近百年来增温总量和增温趋势皆高于全球平均水平, 气候变暖明显(丁一汇和王会军, 2015)。横断山区是我国西南纵向岭谷区的主要组成部分, 是世界范围内生物多样性最为关键的核心区域, 随着气候变化与人类活动的相互作用, 横断山区年平均气温、季风期及非季风期气温均逐年升高(李宗省等, 2010)。

物候被认为是气候变化的“指纹” (Root et al., 2003), 是响应温度变化最敏感、最容易观察到的特征(Badeck et al., 2004), 也是研究生态系统响应气候变化机制的重要途径(Jonasson et al., 1993)。受气候变化的影响, 陆地区域植物物候呈现出不同程度的春季物候提前和秋季物候延迟(Schwartz & Reiter, 2000; Pe?uelas & Filella, 2001; Menzel et al., 2006)。繁殖物候作为植物物候的重要组成部分, 在全球变暖背景下的植物物候研究中备受关注, 然而关于植物繁殖物候对温度变化响应的研究并未得出一致的结论(Wolkovich et al., 2012)。部分研究表明, 在温度升高的情况下, 植物花期呈现出不同程度的提前(Beaubien & Freeland, 2000; Cleland et al., 2006; Amano et al., 2010)。也有研究显示, 温度升高也可能对植物繁殖物候不产生影响(Hollister et al., 2005), 甚至增温会导致植物繁殖物候的延迟(Dorji et al., 2013)。植物繁殖物候速率是繁殖物候特征的重要部分, 对增温的响应也呈现不同的结果。有研究认为增温在改变植物繁殖物候各个状态的同时, 也加快了植物繁殖生长的速率, 最终表现为缩短的繁殖物候期(Post et al., 2008; Gugger et al., 2015)。也有研究表明, 增温后, 植物花期和果期的长度不发生改变(Price & Waser, 1998), 繁殖物候期总的长度也未发生明显变化(Post et al., 2008), 即增温虽然能够提前繁殖物候的各个阶段, 并不改变植物繁殖的速率。这些矛盾的繁殖物候的研究都是使用单个的发育阶段作为评估物候对气候变化响应的指标, 而植物发育是一个连续的过程, 早期的发育阶段会对后期的发育阶段产生一定的限制作用(Post et al., 2008), 甚至可能影响后期阶段对气候变化的响应。因此, 使用单个的物候阶段作为观测指标并不能准确地反映植物物候对气候变化的响应(Wolkovich et al., 2012; Iler et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2014)。

在全球变暖的背景下, 普遍认为高海拔和高纬度地区增温幅度更大(Thomas et al., 2004), 高山生态系统对温度升高的响应也更加迅速和敏感(Pepin et al., 2015)。很多研究发现, 增温显著降低了高寒草甸物种多样性((Klein et al., 2004; Yang et al., 2015), 改变了群落中物种的繁殖物候(Liu et al., 2011; Dorji et al., 2013), 且不同的物种显示出不同的物候增温效应, 这种效应又可能反过来影响植物群落的结构和组成。但是这些研究大部分集中在青藏高原典型的高寒草地生态系统, 基于高山生态系统的高寒草甸物候特征的相关研究鲜见报道。横断山区是青藏高原的重要组成部分, 也是全球中低纬度重要的山系, 研究该地区生态系统对气候变化的响应对研究全球变暖问题有着重要意义。本研究以横断山中段贡嘎山地区的高山草甸为研究对象, 采用开顶式增温箱(OTC)模拟气候变暖, 跟踪调查增温4年后两种优势物种——银叶委陵菜(Potentilla leuconota)和珠芽拳参(Polygonum viviparum)物候序列特征, 旨在阐明以下两个科学问题: (1)单个的繁殖物候阶段是否能真实准确地刻画高寒植物的物候特征对气候变暖的响应? (2)高山植物的繁殖物候对气候变暖的响应是否存在种间差异?本研究的结论不仅可为全球变暖背景下高山生态系统种子资源利用与保护提供理论数据, 同时也可为高山草甸响应未来气候变暖的模型研究提供基础数据和理论依据。

1 材料和方法

1.1 研究区域概况

贡嘎山(29.33°-30.33° N和101.50°-102.25° E)位于青藏高原的东南缘, 横断山区大雪山脉的中南段, 该地区属于亚热带温暖湿润季风区与青藏高原东部高原温带半湿润区的过渡带上, 年平均气温4 ℃, 年空气湿度90%左右, 每年5-10月为明显的雨季, 雨季降水量超过年降水量的80%。研究区域位于贡嘎山东坡雅加埂峡谷内, 群落物种组成丰富, 土壤发育为高山草甸土, 年降水量为1 100 mm。1.2 试验设计

本实验以分布在贡嘎山东坡雅加埂林线以上的高山草甸为研究对象(29.89° N, 102.02° E, 海拔3 850 m), 研究样地面积为20 m × 20 m, 样地在7月气温达到最高, 80%降水集中在生长季。研究样地草本层主要以多年生草本为主, 优势种为银叶委陵菜、珠芽拳参, 伴生薹草属(Carex)、风毛菊属(Saussurea)植物以及禾本科植物。模拟增温采用国际冻原计划所采用的被动式增温方法, 即开顶式增温箱(OTC), 在样地内建立开顶式小暖室。箱体高40 cm, 底部和顶部均为正六边形, 上部开口边长为60 cm, 斜边与地面的夹角均为60°。整个样地分为7个小区, 每个小区内设置对照和OTC增温样方, 对照和增温样方大小均为25 cm × 25 cm, 小区之间距离3-5 m。实验样地用围栏封育, 在2012年6月初完成整个实验样方的布置。1.3 数据收集

样地附近建立气象站(HOBO, Oneset, Boston, USA), 它可以提供整个样地的各种气象要素参数, 包括降水量、空气温度以及地下5 cm和20 cm的温度和土壤含水量; 同时, OTC内外布设传感器和数据采集器(MG-EM50, Decagon, Pullman, USA), 监测对照和增温箱内外的空气和土壤的温湿度, 每10 min采集一次数据。物候数据的收集: 选择该区域两种优势物种——银叶委陵菜和珠芽拳参跟踪调查繁殖物候, 其中珠芽拳参不记录胎生花序。银叶委陵菜花和珠芽拳参属于多年生草本植物, 银叶委陵菜平均花芽萌发期为6月13日(儒略日: 166 ± 17天), 珠芽拳参平均花芽萌发期为6月22日(儒略日: 176 ± 4天), 属于中花期植物类型。将物候分为花芽期、开花期、凋谢期和种子成熟期4个阶段, 每个阶段又分为开始、峰值和结束3个状态。花芽期指从花芽形成可见到完全开放前的阶段; 开花期指花冠完全开放的持续阶段; 凋谢期指从花冠枯萎到果实完全成熟之前的阶段; 果实成熟期, 银叶委陵菜是果实变红并膨大的持续阶段, 珠芽拳参是指果实开始凋落到完全掉落的阶段。在野外观测期间, 分别观测记录两个物种处于各物候阶段繁殖单位的数量, 以该年的1月1日为第一天, 将记录日期转化为儒略日。每个物候阶段的开始日期为首次记录到该阶段的日期, 峰值日期为该物候阶段记录数量达到最大值的日期, 结束日期为该物候阶段最后一次记录日期, 同时各个物候阶段从开始到结束日期的持续天数记作该阶段的持续时间。相邻两阶段峰值之间相差的天数定义为阶段间过渡时间。调查时间从2016年5月下旬到9月底, 每周进行一次观测记录。由于物种的个体差异性, 在对照和增温样方的野外观测中, 分别只有4个小区中能观测到两物种的繁殖物候数据。

1.4 数据分析

所有数据用Excel进行整理, R软件(R 3.3.2, http://www.R-project.org/)进行分析和作图。利用广义混合线性模型检验增温与对照之间各指标的差异显著性, 其中, 对于物候序列, 将各状态所在的儒略日作为响应变量; 对于各物候阶段长度、过渡状态及整个繁殖周期长度, 将指标的天数作为响应变量, 增温处理为固定效应, 样方所在的小区为随机效应。2 结果

2.1 OTC的增温效应

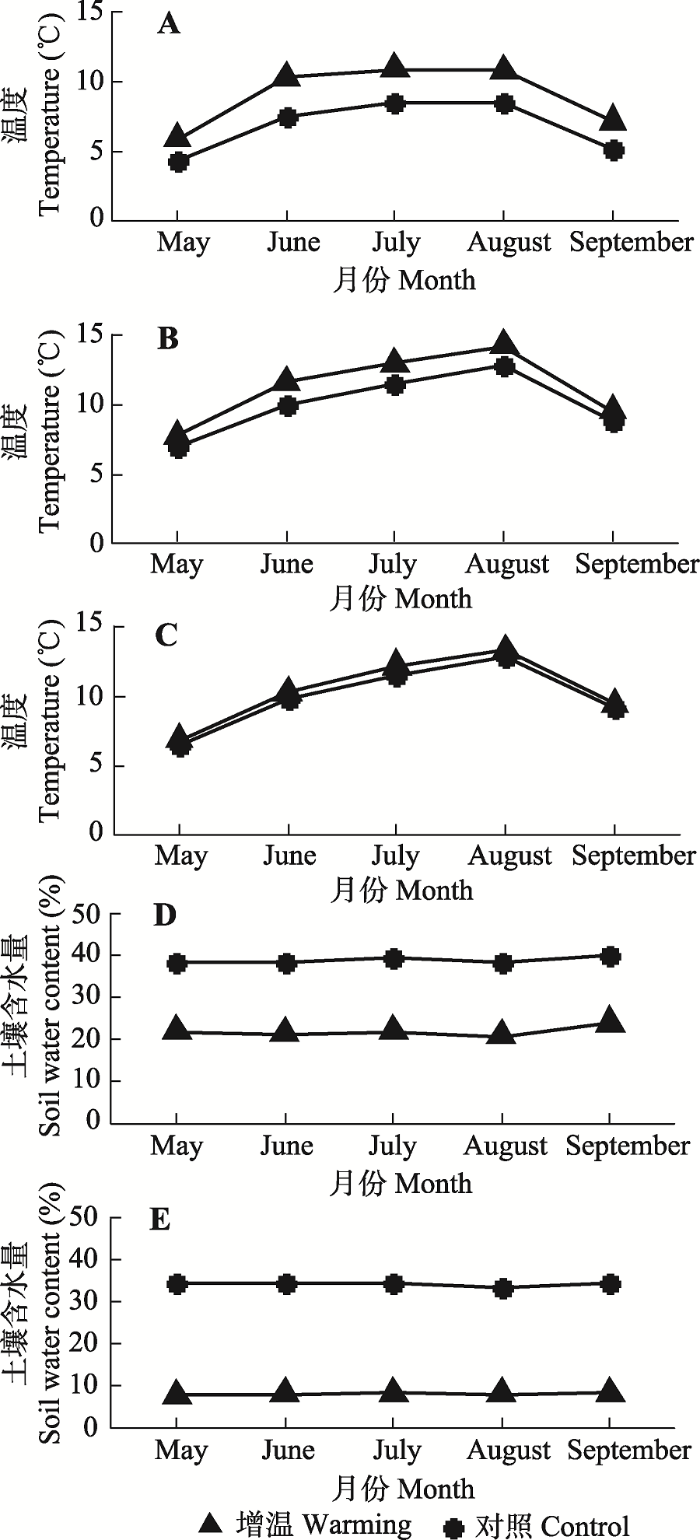

OTC的应用, 使得温室内微气候趋于暖干化。植物生长季内, 箱体内空气温度升高1.53-2.79 ℃, 5 cm土层温度和20 cm土层温度分别比对照升高0.66-1.58 ℃和0.27-0.75 ℃, 5 cm土层含水量和20 cm土层含水量分别比对照减少15.8%-17.7%和25.6%-26.7% (图1)。图1

新窗口打开|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT

新窗口打开|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT图1生长季开顶式增温箱内外空气和土壤的月平均温度、月平均含水量。A, 月平均气温。B, 土壤5 cm深月平均温度。C, 土壤20 cm深月平均温度。D, 土壤5 cm深月平均含水量。E, 土壤20 cm深月平均含水量。

Fig. 1Monthly mean air temperature, soil temperature, and soil water content inside and outside the open-top chambers during the growing season. A, Monthly mean air temperature. B, Monthly mean soil temperature at 5 cm soil depth. C, Monthly mean soil temperature at 20 cm soil depth. D, Monthly mean soil water content at 5 cm soil depth. E, Monthly mean soil water content at 20 cm soil depth.

2.2 物候序列对增温的响应

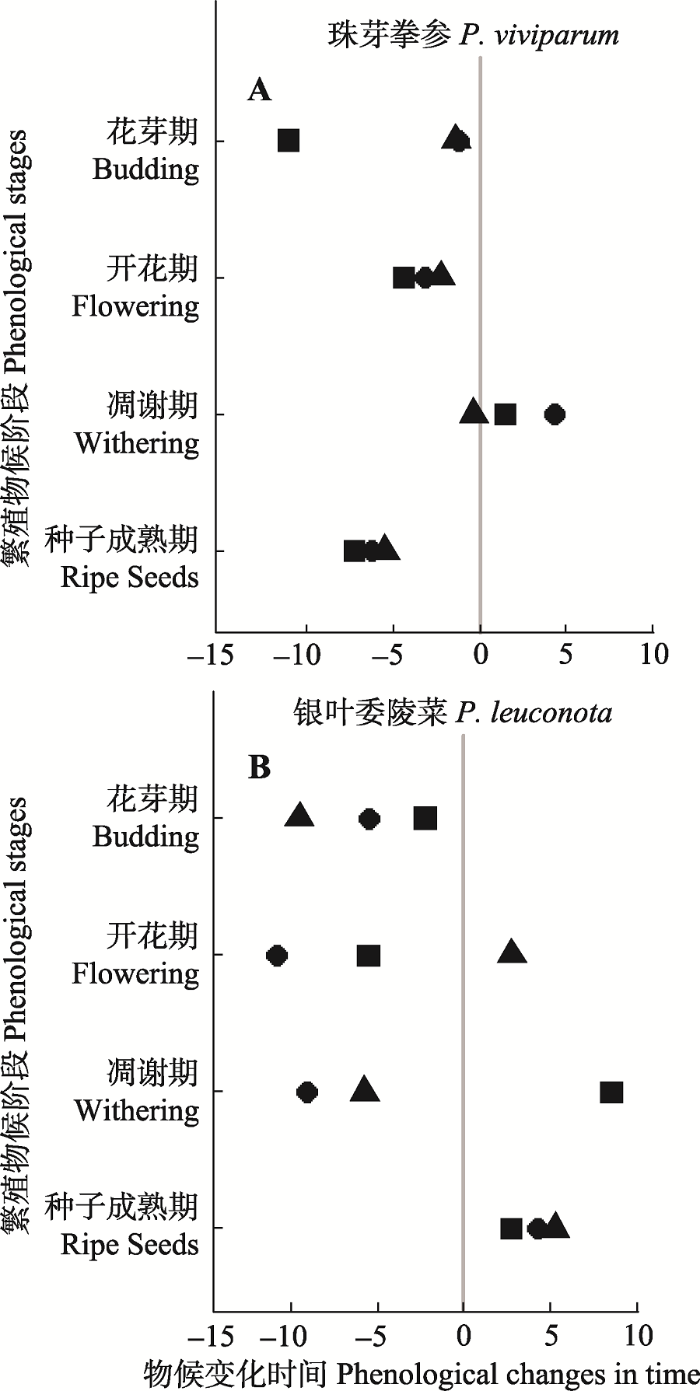

不同物种物候序列对模拟增温的响应方式(提前或推迟)和敏感程度存在一定差异(图2)。随着温度增加, 珠芽拳参花芽期长度缩短12天(p < 0.05), 同时其起始、峰值和结束日期分别提前1天、1.5天和11天; 开花期长度不变, 其起始、峰值和结束日期分别提前3天、2天和-2天; 凋谢期长度不变, 起始、峰值和结束日期分别提前-4天、0天和-1天; 种子成熟期起始、峰值和结束日期分别提前6天、5天和7天, 差异不显著(表1)。银叶委陵菜花芽期长度不变, 同时其起始、峰值和结束日期分别提前5.5天、9.5天和2天; 开花期长度不变, 其起始、峰值和结束日期分别提前11天、-3天和6天; 凋谢期长度不变, 其起始、峰值和结束日期分别提前9天、6天和-9天; 种子成熟期起始、峰值和结束日期分别延迟4天、5天和3天, 差异不显著(表1)。图2

新窗口打开|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT

新窗口打开|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT图2珠芽拳参(A)和银叶委陵菜(B)物候序列变化。■、▲和●分别表示各个阶段的起始、峰值和结束状态。负值表示处理与对照相比提前的天数, 正值表示与对照相比延迟的天数。

Fig. 2Phenological shifts at the sequence of Polygonum viviparum (A) and Potentilla leuconota (B). ■, ▲ and ● symbol represent a phenological shift of first, peak, and last of the four stages, respectively. Negative value represents earlier stations than control in days, and the positive value represents delayed stations than control in days. OTCs, open-top chambers.

Table 1

表1

表1各物候指标对模拟增温响应的参数统计

Table 1

| 阶段 Stage | 状态 Station | 银叶委陵菜 Potentilla leuconota | 珠芽拳参 Polygonum viviparum | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 截距 Intercept | OTCs | N | 截距 Intercept | OTCs | ||

| 花芽期 Budding | 开始 First | 6 | 5.11*** | -0.03 | 13 | 5.19*** | 0.01 |

| 峰值 Peak | 6 | 5.17 *** | -0.05 | 13 | 5.19*** | 0.01 | |

| 结束 Last | 6 | 5.23*** | -0.01 | 13 | 5.28*** | 0.02 | |

| 开花期 Flowering | 开始 First | 8 | 5.17*** | -0.06 | 10 | 5.28*** | -0.02 |

| 峰值 Peak | 8 | 5.18*** | 0.02 | 10 | 5.30*** | -0.01 | |

| 结束 Last | 8 | 5.27*** | -0.02 | 10 | 5.33*** | -0.02 | |

| 凋谢期 Withering | 开始 First | 8 | 5.18*** | -0.05 | 13 | 5.25*** | 0.02 |

| 峰值 Peak | 8 | 5.27 *** | -0.03 | 13 | 5.30*** | 0.01 | |

| 结束 Last | 8 | 5.36 *** | 0.04 | 13 | 5.33*** | 0.01 | |

| 种子成熟期 Ripe seeds | 开始 First | 8 | 5.23*** | 0.02 | 12 | 5.36*** | -0.02 |

| 峰值 Peak | 8 | 5.37 *** | 0.02 | 12 | 5.38*** | -0.02 | |

| 结束 Last | 8 | 5.47*** | 0.01 | 12 | 5.41*** | -0.03 | |

新窗口打开|下载CSV

2.3 各个物候阶段持续时间对增温的响应

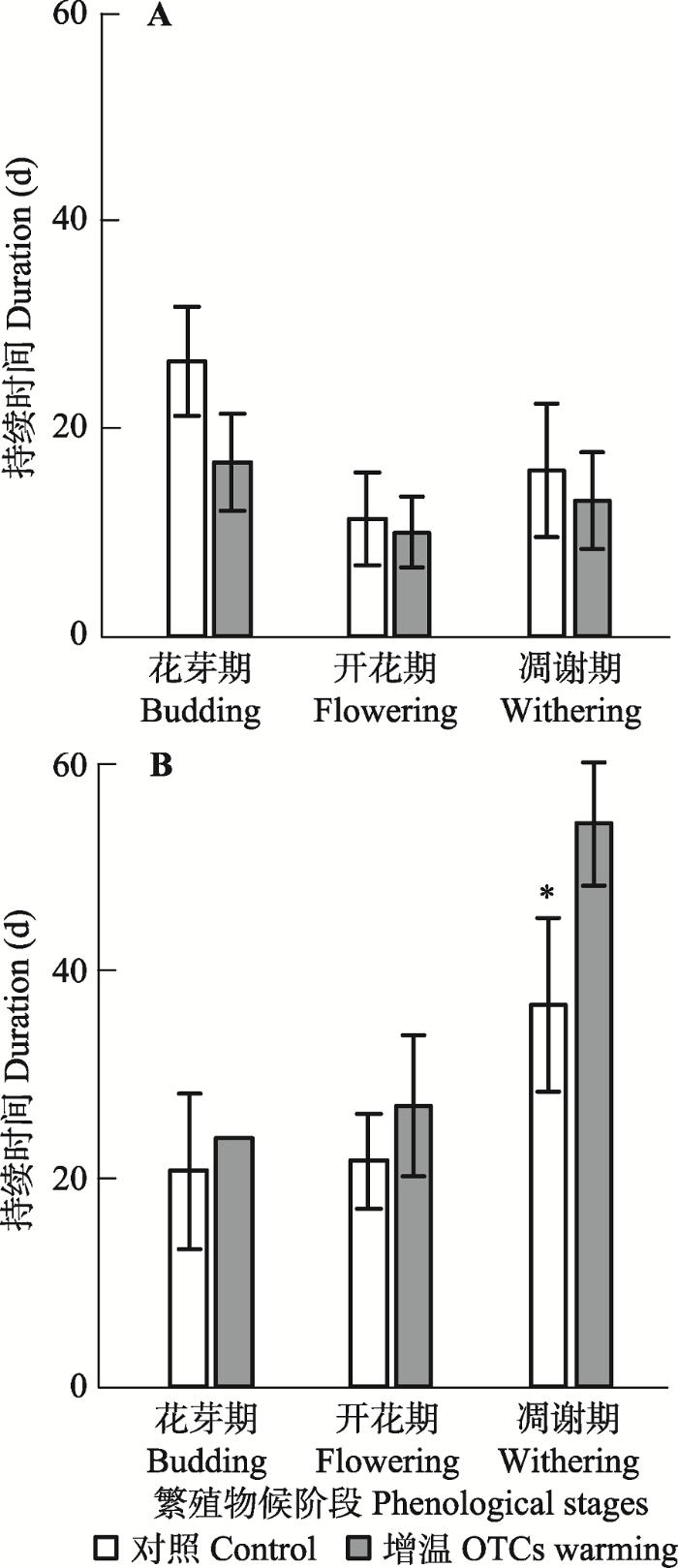

增温导致珠芽拳参各物候持续时段缩短, 银叶委陵菜延长, 两物种物候持续时段对增温的响应行为相反, 且银叶委陵菜对增温的响应更为强烈(图3)。模拟增温后, 珠芽拳参的花芽期、开花期和凋谢期持续时间分别缩短了12天(p < 0.05)、2天和1天, 而银叶委陵菜的花芽期、开花期和凋谢期持续时间分别延长了8天、5天和17天(p > 0.05)。图3

新窗口打开|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT

新窗口打开|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT图3开顶式增温箱模拟增温对珠芽拳参(A)和银叶委陵菜(B)各阶段持续时间长度的影响(平均值±标准误差)。

Fig. 3Effects of open-top chambers (OTCs) warming on the duration of each stage of Polygonum viviparum (A) and Potentilla leuconota (B)(mean ± SE).

2.4 各个物候阶段间过渡时间对增温的响应

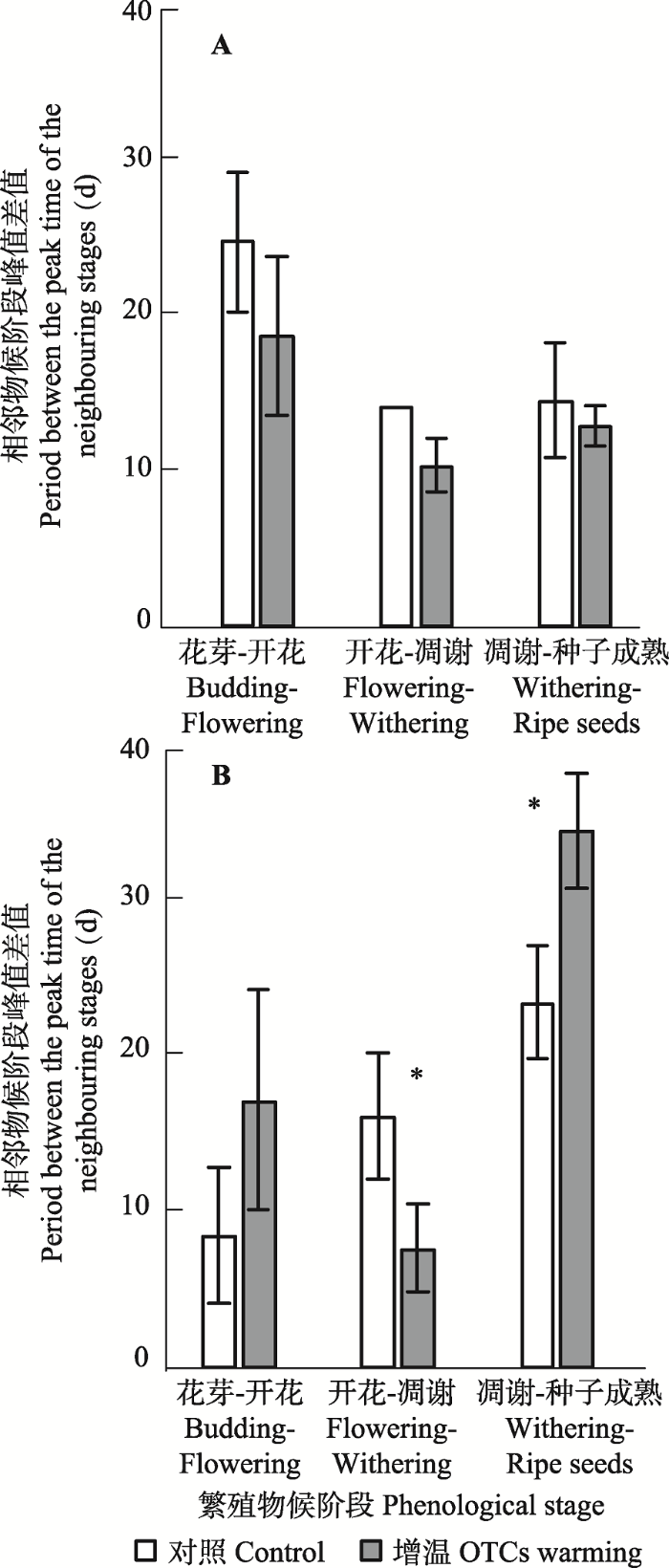

模拟增温导致珠芽拳参各阶段的过渡期不同程度地缩短, 银叶委陵菜的响应却不一致(图4)。其中, 珠芽拳参从花芽期到开花期长度、开花期到凋谢期长度、凋谢期到种子成熟期长度不发生改变。银叶委陵菜从花芽期到开花期长度不变, 开花期到凋谢期缩短了8天(p < 0.05), 凋谢期到种子成熟期长度延长11天(p < 0.05)。图4

新窗口打开|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT

新窗口打开|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT图4开顶式增温箱模拟增温对珠芽拳参(A)和银叶委陵菜(B)相邻物候阶段峰值期相差天数的影响(平均值±标准误差)。

Fig. 4Effects of open-top chambers (OTCs) warming on the period between the peak time of the neighboring stages of Polygonum viviparum (A) and Potentilla leuconota (B) (mean ± SE).

2.5 繁殖周期对增温的响应

增温导致珠芽拳参繁殖周期缩短、银叶委陵菜繁殖周期延长。增温使得珠芽拳参的花芽期起始时间提前, 也使得种子成熟起始时间得以提前, 最终表现为繁殖物候期缩短6天。增温导致银叶委陵菜花芽起始时间提前, 种子成熟的起始时间延迟, 最终表现为繁殖物候期延长8天。增温造成珠芽拳参的繁殖加快, 银叶委陵菜的繁殖延缓。3 讨论

增温改变了横断山区高山草甸珠芽拳参和银叶委陵菜的物候, 且同一物种不同物候阶段(花芽、开花、凋谢和果实成熟)对增温的响应方式(提前或推迟)和响应程度存在一定的差异, 甚至同一物候阶段内不同状态(开始、峰值和结束)对增温的响应都存在差异。同一物种的不同繁殖阶段对环境变化表现出不同的响应方式和敏感性, CaraDonna等(2014)整合亚高山高寒草甸60个物种长期物候资料发现, 研究区域内植物开花阶段的各个状态在增温处理下响应出现不同程度的提前, 在温度每10年增加(0.4 ± 0.1) ℃的情况下, 开花起始时间每10年提前(3.3 ± 0.24) d, 开花峰值提前(2.5 ± 0.20) d, 开花结束时间提前(1.5 ± 0.42) d。Post等(2008)对格陵兰岛西部的植物群落增温2年后发现, 在OTC增温效果为2 ℃左右的情况下, 卷耳属植物Cerastium alpinum花芽起始时间提前2.5 d, 开花时间不变。由此可见, 植物各物候阶段对环境变化的响应存在可塑性差异。Dorji等(2013)研究发现模拟增温对钉柱委陵菜(Potentilla saundersiana)的花芽起始期、开花起始期等物候指标不产生显著影响, 本研究通过银叶委陵菜和珠芽拳参的观测发现, 若仅采取与Dorji等(2013)相同的物候阶段作为响应温度变化的指标, 也可得到相同的结论, 认为模拟增温不改变两种植物的繁殖物候。但是若考虑整个繁殖序列, 则显示模拟增温显著延长了银叶委陵菜凋谢期长度、凋谢到成熟过渡期长度, 甚至显著缩短了开花到凋谢期长度。因此, 即使模拟增温对单个或几个物候阶段不产生显著影响, 也不能得出环境变化对该物种繁殖物候不产生影响的结论。同时Gugger等(2015)移位增温实验中, 以植物某一物候阶段的起始到下一物候阶段的峰值所经历的天数作为该阶段的持续时间, 结果显示增温显著缩短了植物凋谢期长度。本研究若仅使用凋谢期到成熟期过渡状态作为响应温度变化的指标, 则可以得出与Gugger (2015)类似的结论: 增温导致银叶委陵菜加速繁殖物候期; 但是若完整地记录银叶委陵菜整个繁殖物候期的长度,则显示增温延长了银叶委陵菜的繁殖物候期(p < 0.1), 单个的物候阶段与整个繁殖期对增温的响应呈现相反的结果, 植物繁殖物候某一阶段的响应与整个繁殖物候期的响应并不一致。因此, 在气候变化背景下对植物繁殖物候的研究中, 即使同一物种使用不同的物候指标也可能得到不同的结论, 甚至得出完全相反的结论, 单个物候阶段并不能准确地反映整个植物物候期对温度变化的响应(CaraDonna et al., 2014; Meng et al., 2016)。

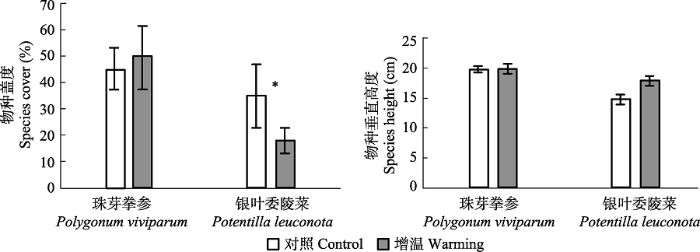

不同物种对增温的响应方式(提前或推迟)和敏感程度存在一定差异。不同繁殖阶段对增温响应的差异还引起植物各物候阶段的持续时间、过渡时间以及繁殖周期发生了变化。Inouye (2008)发现在生长季会出现霜冻的地区, 霜冻会使得该地区提前开花植物的花遭受不同程度的损失, 因此植物会选择缩短繁殖期以提高繁殖成功率。Post等(2008)对3种植物的模拟增温研究中也发现, 增温后每种植物至少有一个繁殖阶段表现为加速。本研究发现增温后, 植物繁殖物候期表现为不变或延长。这可能是增温后不同的植物表现出不同的响应方式, 例如, Totland和Schulte-Herbrüggen (2003)研究发现增温4年并不改变卷耳属(Cerastium)植物开花的持续时间。Arft等(1999)的meta分析结果显示模拟增温2年后植物对增温的响应开始减弱, 本研究是在增温后的第5年开始观测记录繁殖物候, 因此无法判断物种繁殖物候在增温初期植物繁殖周期对增温的响应。同时, 植物繁殖物候特征对增温响应的种间差异, 可能是植物个体为避免对土壤中水分和养分利用效率竞争、营养生长期的过度重叠, 以及植物叶片对光照需求的竞争, 最大化利用资源的一种适应环境的结果(Tilman et al., 1997; Dudgeon et al., 1999; Forrest & Miller-Rushing, 2010)。这种植物繁殖物候期的种间差异是物种长期进化过程中不断适应环境的结果, 也是植物降低种间竞争并维持群落水平物种共存的重要机制(Cleland et al., 2006)。本研究在群落地上净初级生产力达到峰值的8月初, 对样方内两物种的垂直高度和盖度进行了调查, 单因素方差分析的结果显示, 增温对珠芽拳参垂直高度和盖度没有显著影响, 而银叶委陵菜的盖度显著降低(p < 0.05), 垂直高度增加不显著(附件I), 垂直高度和盖度的变化表明两种植物在应对环境变化中采取了不同的响应策略。优势物种在群落中高度、盖度的不同变化可能会改变物种之间的竞争力(Pe?uelas et al., 2002), 引起物种物候繁殖策略的改变, 进而导致种群动态波动(Price & Waser, 1998)和植物与传粉者之间关系的变化(Memmott et al., 2007), 最终直接或间接地影响群落的结构和功能(Pe?uelas & Filella, 2009)。

综上所述, 完整的物候序列比单个物候阶段更能准确地评估植物繁殖物候对气候变暖的响应, 建议在相关模型的运用中考虑完整的繁殖物候序列。同时, 增温改变了高山草甸群落中两优势物种的繁殖物候时间和繁殖速率, 且在对增温的响应程度及方式上存在物种间的差异。可见, 高山生态系统植物物候对气候变化的响应并不是单一地朝着一个方向变化, 而是存在不同繁殖阶段的响应差异以及显著的种间差异, 这些物候差异为研究高山植物群落应对气候变化的响应格局和方向提供了可能的内在机制解释, 为该区域山地物种保育和生态系统功能研究提供了理论依据, 同时为准确地评估区域陆地生态系统应对气候变化的模型预估提供了基础数据和理论支持。

附件

附件I

新窗口打开|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT

新窗口打开|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT附件I增温后物种盖度和垂直高度的变化(平均值±标准误差)

Appendix IChanges in coverage and height of the two species under experimental warming (mean ± SE). *, p < 0.05

致谢

参考文献 原文顺序

文献年度倒序

文中引用次数倒序

被引期刊影响因子

DOI:10.1098/rspb.2010.0291URLPMID:20375052 [本文引用: 1]

Abstract Widespread concerns about global biodiversity loss have led to a growing demand for indices of biodiversity status. Today, climate change is among the most serious threats to global biodiversity. Although many studies have revealed phenological responses to climate change, no long-term community-level indices have been developed. We derived a 250-year index of first flowering dates for 405 plant species in the UK for assessing the impact of climate change on plant communities. The estimated community-level index in the most recent 25 years was 2.2-12.7 days earlier than any other consecutive 25-year period since 1760. The index was closely correlated with February-April mean Central England Temperature, with flowering 5.0 days earlier for every 1 degrees C increase in temperature. The index was relatively sensitive to the number of species, not records per species, included in the model. Our results demonstrate how multi-species, multiple-site phenological events can be integrated to obtain indices showing trends for each species and across species. This index should play an important role in monitoring the impact of climate change on biodiversity. Furthermore, this approach can be extended to incorporate data from other taxa and countries for evaluating cross-taxa and cross-country phenological responses to climate change.

DOI:10.1890/0012-9615(1999)069[0491:ROTPTE]2.0.CO;2URL

The International Tundra Experiment (ITEX) is a collaborative, multisite experiment using a common temperature manipulation to examine variability in species response across climatic and geographic gradients of tundra ecosystems. ITEX was designed specifically to examine variability in arctic and alpine species response to increased temperature. We compiled from one to four years of experimental data from 13 different ITEX sites and used meta-analysis to analyze responses of plant phenology, growth, and reproduction to experimental warming. Results indicate that key phenological events such as leaf bud burst and flowering occurred earlier in warmed plots throughout the study period; however, there was little impact on growth cessation at the end of the season. Quantitative measures of vegetative growth were greatest in warmed plots in the early years of the experiment, whereas reproductive effort and success increased in later years. A shift away from vegetative growth and toward reproductive effort and success in the fourth treatment year suggests a shift from the initial response to a secondary response. The change in vegetative response may be due to depletion of stored plant reserves, whereas the lag in reproductive response may be due to the formation of flower buds one to several seasons prior to flowering. Both vegetative and reproductive responses varied among life-forms; herbaceous forms had stronger and more consistent vegetative growth responses than did woody forms. The greater responsiveness of the herbaceous forms may be attributed to their more flexible morphology and to their relatively greater proportion of stored plant reserves. Finally, warmer, low arctic sites produced the strongest growth responses, but colder sites produced a greater reproductive response. Greater resource investment in vegetative growth may be a conservative strategy in the Low Arctic, where there is more competition for light, nutrients, or water, and there may be little opportunity for successful germination or seedling development. In contrast, in the High Arctic, heavy investment in producing seed under a higher temperature scenario may provide an opportunity for species to colonize patches of unvegetated ground. The observed differential response to warming suggests that the primary forces driving the response vary across climatic zones, functional groups, and through time.

DOI:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2004.01059.xURL [本文引用: 1]

Climate change effects on seasonal activity in terrestrial ecosystems are significant and well documented, especially in the middle and higher latitudes. Temperature is a main driver of many plant developmental processes, and in many cases higher temperatures have been shown to speed up plant development and lead to earlier switching to the next ontogenetic stage. Qualitatively consistent advancement of vegetation activity in spring has been documented using three independent methods, based on ground observations, remote sensing, and analysis of the atmospheric CO 2 signal. However, estimates of the trends for advancement obtained using the same method differ substantially. We propose that a high fraction of this uncertainty is related to the time frame analysed and changes in trends at decadal time scales. Furthermore, the correlation between estimates of the initiation of spring activity derived from ground observations and remote sensing at interannual time scales is often weak. We propose that this is caused by qualitative differences in the traits observed using the two methods, as well as the mixture of different ecosystems and species within the satellite scenes.

DOI:10.1007/s004840000050URLPMID:10993558 [本文引用: 1]

Abstract Warmer winter and spring temperatures have been noted over the last century in Western Canada. Earlier spring plant development in recent decades has been reported for Europe, but not for North America. The first-bloom dates for Edmonton, Alberta, were extracted from four historical data sets, and a spring flowering index showed progressively earlier development. For Populus tremuloides, a linear trend shows a 26-day shift to earlier blooming over the last century. The spring flowering index correlates with the incidence of El Ni01±o events and with Pacific sea-surface temperatures.

DOI:10.1073/pnas.1323073111URL [本文引用: 2]

Phenology—the timing of biological events—is highly sensitive to climate change. However, our general understanding of how phenology responds to climate change is based almost solely on incomplete assessments of phenology (such as first date of flowering) rather than on entire phenological distributions. Using a uniquely comprehensive 39-y flowering phenology dataset...

DOI:10.1073/pnas.0600815103URLPMID:16954189 [本文引用: 2]

Shifting plant phenology (i.e., timing of flowering and other developmental events) in recent decades establishes that species and ecosystems are already responding to global environmental change. Earlier flowering and an extended period of active plant growth across much of the northern hemisphere have been interpreted as responses to warming. However, several kinds of environmental change have the potential to influence the phenology of flowering and primary production. Here, we report shifts in phenology of flowering and canopy greenness (Normalized Difference Vegetation Index) in response to four experimentally simulated global changes: warming, elevated CO , nitrogen (N) deposition, and increased precipitation. Consistent with previous observations, warming accelerated both flowering and greening of the canopy, but phenological responses to the other global change treatments were diverse. Elevated CO and N addition delayed flowering in grasses, but slightly accelerated flowering in forbs. The opposing responses of these two important functional groups decreased their phenological complementarity and potentially increased competition for limiting soil resources. At the ecosystem level, timing of canopy greenness mirrored the flowering phenology of the grasses, which dominate primary production in this system. Elevated CO delayed greening, whereas N addition dampened the acceleration of greening caused by warming. Increased precipitation had no consistent impacts on phenology. This diversity of phenological changes, between plant functional groups and in response to multiple environmental changes, helps explain the diversity in large-scale observations and indicates that changing temperature is only one of several factors reshaping the seasonality of ecosystem processes.

[本文引用: 1]

[本文引用: 1]

DOI:10.1111/gcb.12059URLPMID:23504784 [本文引用: 2]

Abstract Global climate change is predicted to have large impacts on the phenology and reproduction of alpine plants, which will have important implications for plant demography and community interactions, trophic dynamics, ecosystem energy balance, and human livelihoods. In this article we report results of a 3-year, fully factorial experimental study exploring how warming, snow addition, and their combination affect reproductive phenology, effort, and success of four alpine plant species belonging to three different life forms in a semiarid, alpine meadow ecosystem on the central Tibetan Plateau. Our results indicate that warming and snow addition change reproductive phenology and success, but responses are not uniform across species. Moreover, traits associated with resource acquisition, such as rooting depth and life history (early vs. late flowering), mediate plant phenology, and reproductive responses to changing climatic conditions. Specifically, we found that warming delayed the reproductive phenology and decreased number of inflorescences of Kobresia pygmaea C. B. Clarke, a shallow-rooted, early-flowering plant, which may be mainly constrained by upper-soil moisture availability. Because K. pygmaea is the dominant species in the alpine meadow ecosystem, these results may have important implications for ecosystem dynamics and for pastoralists and wildlife in the region. 2012 Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

DOI:10.1890/0012-9615(1999)069[0331:COSSIA]2.0.CO;2URL [本文引用: 1]

The lower intertidal zone (0.0 to + 1.0 m mean low water [MLW]) ofky shores in New England is a space-limited community occupied by two similar rhodophyte seaweeds, Chondrus crispus and Mastocarpus stellatus, that overlap broadly in their use of three essential resources: space, light, and nutrients. C. crispus coexists primarily with the prostrate-crust generation of M. stellatus lower on the shore (less than +0.35 m MLW) and with the alternate upright-frond generation higher on the shore (greater than +0.35 m MLW). Our objectives were to determine (1) whether these two species compete and (2) if so, what process(es) enable their coexistence. Upright fronds of M. stellatus transplanted to the lowest intertidal zone (less than +0.25 m MLW) where C. crispus predominates grew faster and showed higher survivorship after 2 yr than those transplanted to areas where M. stellatus predominates. However, the failure of upright fronds of M. stellatus to consistently recruit limits their abundance in the lowest zone and reduces the frequency of preemptive competition by C. crispus. Moreover, when M. stellatus was grown in combination with fronds of C. crispus in this zone, the dominant competitor C. crispus suppressed the growth and reproductive output of M. stellatus fronds. Neither species was significantly consumed by littorinid gastropods in field and laboratory experiments, indicating that herbivory does not control patterns of coexistence. In the low zone, coexistence between C. crispus and M. stellatus appears to be mediated primarily by disturbances from winter storm waves that remove large, fast-growing C. crispus fronds and limit its abundance. Coexistence of C. crispus fronds and M. stellatus crusts in this zone may also result from their different patterns of resource use. In contrast to the low zone, the slow growth of C. crispus in the mid-low zone (approximately +0.5 m MLW) prevented the overgrowth of fronds of M. stellatus and, hence, prevented competition from

DOI:10.1098/rstb.2010.0145URLPMID:2981948 [本文引用: 1]

Phenology affects nearly all aspects of ecology and evolution. Virtually all biological phenomena-from individual physiology to interspecific relationships to global nutrient fluxes-have annual cycles and are influenced by the timing of abiotic events. Recent years have seen a surge of interest in this topic, as an increasing number of studies document phenological responses to climate change. Much recent research has addressed the genetic controls on phenology, modelling techniques and ecosystem-level and evolutionary consequences of phenological change. To date, however, these efforts have tended to proceed independently. Here, we bring together some of these disparate lines of inquiry to clarify vocabulary, facilitate comparisons among habitat types and promote the integration of ideas and methodologies across different disciplines and scales. We discuss the relationship between phenology and life history, the distinction between organismal- and population-level perspectives on phenology and the influence of phenology on evolutionary processes, communities and ecosystems. Future work should focus on linking ecological and physiological aspects of phenology, understanding the demographic effects of phenological change and explicitly accounting for seasonality and phenology in forecasts of ecological and evolutionary responses to climate change.

DOI:10.1093/aob/mcv155URLPMID:4640129 [本文引用: 1]

BACKGROUND AND AIMS: Recent global changes, particularly warming and drought, have had worldwide repercussions on the timing of flowering events for many plant species. Phenological shifts have also been reported in alpine environments, where short growing seasons and low temperatures make reproduction particularly challenging, requiring fine-tuning to environmental cues. However, it remains unclear if species from such habitats, with their specific adaptations, harbour the same potential for phenological plasticity as species from less demanding habitats. METHODS: Fourteen congeneric species pairs originating from mid and high elevation were reciprocally transplanted to common gardens at 1050 and 2000 a.s.l. that mimic prospective climates and natural field conditions. A drought treatment was implemented to assess the combined effects of temperature and precipitation changes on the onset and duration of reproductive phenophases. A phenotypic plasticity index was calculated to evaluate if mid- and high-elevation species harbour the same potential for plasticity in reproductive phenology. KEY RESULTS: Transplantations resulted in considerable shifts in reproductive phenology, with highly advanced initiation and shortened phenophases at the lower (and warmer) site for both mid- and high-elevation species. Drought stress amplified these responses and induced even further advances and shortening of phenophases, a response consistent with an 'escape strategy'. The observed phenological shifts were generally smaller in number of days for high-elevation species and resulted in a smaller phenotypic plasticity index, relative to their mid-elevation congeners. CONCLUSIONS: While mid- and high-elevation species seem to adequately shift their reproductive phenology to track ongoing climate changes, high-elevation species were less capable of doing so and appeared more genetically constrained to their specific adaptations to an extreme environment (i.e. a short, cold growing season).

DOI:10.1890/04-0520URL [本文引用: 1]

The response of plants to temperature has gained renewed interest as researchers speculate on the biotic response to climate change. It is of particular interest in the Arctic, due to recent warming trends and anticipated continued warming for the region. This long-term, multispecies study confirms that changes in temperature affect the functioning of plants in their natural environment. It also demonstrates that the influence of temperature should be considered in the context of natural variability within a given location. The study examined natural temperature gradients, interannual climate variation, and experimental warming at sites near Barrow (71° 18′ N, 156° 40′ W) and Atqasuk (70° 29′ N, 157° 25′ W) in northern Alaska, USA. At each of the four sites, 24 plots were experimentally warmed for 5-7 years with small, open-top chambers, and plant growth and phenology were monitored; an equal number of unmanipulated control plots were monitored. The response of seven traits from 32 plant species occurring in at least one site is reported when there were at least three years of recordings. Plants responded to temperature in 49% of the measured traits of a species in a site. The most common response to warming was earlier phenological development and increased growth and reproductive effort. However, the total response of a species, for all traits examined, was individualistic and varied among sites. In 14% of the documented responses, the plant trait was correlated with thawing degree-day totals from snowmelt (TDDsm), and temperature was considered the dominant factor. In 35% of the documented responses, the plant trait responded to warming, but the interannual variation in the trait was not correlated with TDDsmand temperature was considered subordinate to other factors. The abundance of temperature responses that were considered subordinate to other factors suggests that prediction of plant response to temperature that does not account for natural variability may overestimate the importance of temperature and lead to unrealistic projections of the rate of vegetation change due to climate warming.

DOI:10.1098/rstb.2012.0489URLPMID:3720060 [本文引用: 1]

Many alpine and subalpine plant species exhibit phenological advancements in association with earlier snowmelt. While the phenology of some plant species does not advance beyond a threshold snowmelt date, the prevalence of such threshold phenological responses within plant communities is largely unknown. We therefore examined the shape of flowering phenology responses (linear versus nonlinear) to climate using two long-term datasets from plant communities in snow-dominated environments: Gothic, CO, USA (1974-2011) and Zackenberg, Greenland (1996-2011). For a total of 64 species, we determined whether a linear or nonlinear regression model best explained interannual variation in flowering phenology in response to increasing temperatures and advancing snowmelt dates. The most common nonlinear trend was for species to flower earlier as snowmelt advanced, with either no change or a slower rate of change when snowmelt was early (average 20% of cases). By contrast, some species advanced their flowering at a faster rate over the warmest temperatures relative to cooler temperatures (average 5% of cases). Thus, some species seem to be approaching their limits of phenological change in response to snowmelt but not temperature. Such phenological thresholds could either be a result of minimum springtime photoperiod cues for flowering or a slower rate of adaptive change in flowering time relative to changing climatic conditions.

DOI:10.1890/06-2128.1URL

[本文引用: 2]

[本文引用: 1]

DOI:10.1111/j.1461-0248.2004.00677.xURL [本文引用: 1]

Abstract We investigated the independent and combined effects of experimental warming and grazing on plant species diversity on the north-eastern Tibetan Plateau, a region highly vulnerable to ongoing climate and land use changes. Experimental warming caused a 26–36% decrease in species richness, a response that was generally dampened by experimental grazing. Higher species losses occurred at the drier sites where N was less available. Moreover, we observed an indirect effect of climate change on species richness as mediated by plant–plant interactions. Heat stress and warming-induced litter accumulation are potential explanations for the species’ responses to experimental warming. This is the first reported experimental evidence that climate warming could cause dramatic declines in plant species diversity in high elevation ecosystems over short time frames and supports model predictions of species losses with anthropogenic climate change.

DOI:10.11821/xb201005006URL [本文引用: 1]

运用样条函数法、线性回归、最小二乘法和趋势分析等方法,对横断山区27个气象站1960-2008年日平均气温和降水资料分析表明,近50年来横断山区气温呈现统计意义上的变暖趋势,其中60和80年代气温相对较低,其他年代则较高,2000-2008时段年均温比多年均值高0.46oC。横断山区年均气温、春季气温、夏季气温、秋季气温和冬季气温的倾向率分别为0.15oC10a-1、0.589oC10a-1、0.153oC10a-1、0.167oC10a-1和0.347oC10a-1,升温幅度表现出随纬度增高而加大的趋势,整个横断山区以沙鲁里山和大雪山南缘区域及梅里雪山地区为中心,春季升温幅度最大,冬季次之。横断山区年降水在60和70年代偏低,80年代以后相对偏高,特别是90年代比多年均值高29.84mm,进入2000年后相较90年代明显下降。横断山区年降水、春季降水、夏季降水、秋季降水和冬季降水倾向率分别为9.09mm10a-1、8.62mm10a-1、-1.5mm10a-1、1.53mm10a-1和1.47mm10a-1,只有春季倾向率通过了显著水平检验;除夏季降水外,其他季节降水均表现出由西南向东北和由南向北递减的趋势,这是纵向岭谷对流经该区的东亚季风和南亚季风同时起着东西向阻隔作用和南北向通道作用的体现。横断山区季风期气温和降水的倾向率分别为0.117oC10a-1和6.01mm10a-1,最为明显的是2000年后季风期降水明显降低;横断山区非季风期气温和降水的倾向率分别为0.25oC10a-1和7.47mm10a-1,均高于季风期。

DOI:10.11821/xb201005006URL [本文引用: 1]

运用样条函数法、线性回归、最小二乘法和趋势分析等方法,对横断山区27个气象站1960-2008年日平均气温和降水资料分析表明,近50年来横断山区气温呈现统计意义上的变暖趋势,其中60和80年代气温相对较低,其他年代则较高,2000-2008时段年均温比多年均值高0.46oC。横断山区年均气温、春季气温、夏季气温、秋季气温和冬季气温的倾向率分别为0.15oC10a-1、0.589oC10a-1、0.153oC10a-1、0.167oC10a-1和0.347oC10a-1,升温幅度表现出随纬度增高而加大的趋势,整个横断山区以沙鲁里山和大雪山南缘区域及梅里雪山地区为中心,春季升温幅度最大,冬季次之。横断山区年降水在60和70年代偏低,80年代以后相对偏高,特别是90年代比多年均值高29.84mm,进入2000年后相较90年代明显下降。横断山区年降水、春季降水、夏季降水、秋季降水和冬季降水倾向率分别为9.09mm10a-1、8.62mm10a-1、-1.5mm10a-1、1.53mm10a-1和1.47mm10a-1,只有春季倾向率通过了显著水平检验;除夏季降水外,其他季节降水均表现出由西南向东北和由南向北递减的趋势,这是纵向岭谷对流经该区的东亚季风和南亚季风同时起着东西向阻隔作用和南北向通道作用的体现。横断山区季风期气温和降水的倾向率分别为0.117oC10a-1和6.01mm10a-1,最为明显的是2000年后季风期降水明显降低;横断山区非季风期气温和降水的倾向率分别为0.25oC10a-1和7.47mm10a-1,均高于季风期。

DOI:10.1890/10-2060.1URL [本文引用: 1]

DOI:10.1111/ele.2007.10.issue-8URL [本文引用: 1]

DOI:10.1016/j.agrformet.2016.04.013URL [本文引用: 1]

Change in individual species phenology is often unsuitable for predicting change in community phenology because of different responses of different species to temperature change. However, few studies have observed community phenological sequences in the field. Here we explore the changes in timing and duration of the community phenological sequence (i.e. onset of leaf-out (OLO), first flower bud (FB), first flowering (FF), first fruiting-set (FFS), post-fruiting vegetation (OPFV), first leaf-coloring (FLC) and complete leaf-coloring (CLC)) along an elevation gradient from 3200 to 3800 m in an alpine meadow on the Tibetan plateau. Our results indicate that OLO and FFS significantly advanced and other timings of phenological events significantly delayed at 3200 m compared with higher elevations (3600 and 3800 m). The flowering duration of the community was shortest and other phenological durations (except budding stage and post-fruiting vegetation stage) were longest at 3200 m. The duration of the growing season decreased as elevation increased, and the ratio of the durations of the reproductive period and growing season was smallest at 3200 m. There were negative correlations between the proportion of early-spring flowering functional group plants and FB, and the durations of leafing and post-fruiting vegetation of the community. Positive correlations were found between the proportion of mid-summer flowering functional group plants in the community and these variables. There were significant negative correlations between flowering duration of the community and annual mean air temperature and soil moisture. Therefore, our results suggest that different community compositions might respond differently to climate change.

DOI:10.1053/jlts.2003.50055URL [本文引用: 1]

Global climate change impacts can already be tracked in many physical and biological systems; in particular, terrestrial ecosystems provide a consistent picture of observed changes. One of the preferred indicators is phenology, the science of natural recurring events, as their recorded dates provide a high-temporal resolution of ongoing changes. Thus, numerous analyses have demonstrated an earlier onset of spring events for mid and higher latitudes and a lengthening of the growing season. However, published single-site or single-species studies are particularly open to suspicion of being biased towards predominantly reporting climate change-induced impacts. No comprehensive study or meta-analysis has so far examined the possible lack of evidence for changes or shifts at sites where no temperature change is observed. We used an enormous systematic phenological network data set of more than 125 000 observational series of 542 plant and 19 animal species in 21 European countries (1971-2000). Our results showed that 78% of all leafing, flowering and fruiting records advanced (30% significantly) and only 3% were significantly delayed, whereas the signal of leaf colouring/fall is ambiguous. We conclude that previously published results of phenological changes were not biased by reporting or publication predisposition: the average advance of spring/summer was 2.5 days decade(-1) in Europe. Our analysis of 254 mean national time series undoubtedly demonstrates that species' phenology is responsive to temperature of the preceding months (mean advance of spring/summer by 2.5 days degrees C-1, delay of leaf colouring and fall by 1.0 day degrees C-1). The pattern of observed change in spring efficiently matches measured national warming across 19 European countries (correlation coefficient r=-0.69, P < 0.001).

DOI:10.1126/science.1066860URLPMID:11679652 [本文引用: 1]

ABSTRACT Animal and plant life cycles are increasingly shown to depend on temperature trends and patterns. In their Perspective, Pe uelas and Filella review the evidence that global warming during the 20th century has affected the growth period of plants and the development and behavior of animals from insects to birds. The authors warn that changes in the interdependence between species could have unpredictable consequences for ecosystems, that the lengthening of the plant growing season contributes to the global increased carbon fixation, and that changes in phenology may affect not only ecosystems but also agriculture and sanitation.

DOI:10.1126/science.1173004URLPMID:19443770 [本文引用: 1]

A longer growing season as a result of climate change will in turn affect climate through biogeochemical and biophysical effects.

DOI:10.1046/j.1365-2486.2002.00489.xURL [本文引用: 1]

Abstract The available data on climate over the past century indicate that the earth is warming. Important biological effects, including changes of plant and animal life cycle events, have already been reported. However, evidence of such effects is still scarce and has been mostly limited to northern latitudes. Here we provide the first long-term (1952 2000) evidence of altered life cycles for some of the most abundant Mediterranean plants and birds, and one butterfly species. Average annual temperatures in the study area (Cardedeu, NE Spain) have increased by 1.4 C over the observation period while precipitation remained unchanged. A conservative linear treatment of the data shows that leaves unfold on average 16days earlier, leaves fall on average 13days later, and plants flower on average 6days earlier than in 1952. Fruiting occurs on average 9days earlier than in 1974. Butterflies appear 11days earlier, but spring migratory birds arrive 15days later than in 1952. The stronger changes both in temperature and in phenophases timing occurred in the last 25years. There are no significant relationships among changes in phenophases and the average date for each phenophase and species. There are not either significant differences among species with different Raunkiaer life-forms or different origin (native, exotic or agricultural). However, there is a wide range of phenological alterations among the different species, which may alter their competitive ability, and thus, their ecology and conservation, and the structure and functioning of ecosystems. Moreover, the lengthening of plant growing season in this and other northern hemisphere regions may contribute to a global increase in biospheric activity.

DOI:10.1038/nclimate2563URL [本文引用: 3]

There is growing evidence that the rate of warming is amplified with elevation, such that high-mountain environments experience more rapid changes in temperature than environments at lower elevations. Elevation-dependent warming (EDW) can accelerate the rate of change in mountain ecosystems, cryospheric systems, hydrological regimes and biodiversity. Here we review important mechanisms that contribute towards EDW: snow albedo and surface-based feedbacks; water vapour changes and latent heat release; surface water vapour and radiative flux changes; surface heat loss and temperature change; and aerosols. All lead to enhanced warming with elevation (or at a critical elevation), and it is believed that combinations of these mechanisms may account for contrasting regional patterns of EDW. We discuss future needs to increase knowledge of mountain temperature trends and their controlling mechanisms through improved observations, satellite-based remote sensing and model simulations.

DOI:10.1890/06-2138.1URL [本文引用: 2]

DOI:10.1890/0012-9658(1998)079[1261:EOEWOP]2.0.CO;2URL [本文引用: 1]

Increasing "greenhouse" gases are predicted to warm the earth by several degrees Celsius during the coming century. At high elevations one likely result is a longer snow-free season, which will affect plant growth and reproduction. We studied flowering and fruiting of 10 angiosperm species in a subalpine meadow over 4 yr, focusing on plant responses to warming by overhead heaters. The 10 species reproduced in a predictable sequence during 3-4 mo between spring snowmelt and fall frosts. Experimental warming advanced the date of snowmelt by almost 1 wk on average, relative to controls, and similarly advanced the mean timing of plant reproduction. This phenological shift was entirely explained by earlier snowmelt in the case of six plant species that flowered early in the season, whereas four later-flowering species apparently responded to other cues. Experimental warming had no detectable effect on the duration of flowering and fruiting, even though natural conditions of early snowmelt were associated with longer duration and greater overlap of reproduction of sequentially flowering species. Fruit set was greater in warmed plots for most species, but this effect was not significant for any species individually. We conclude that global warming will cause immediate phenological shifts in plant communities at high elevations, mediated largely through changes in timing of snowmelt. Shifts on longer time scales are also likely as plant fitnesses, population dynamics, and community structure respond to altered phenology of species relative to one another and to animal mutualists and enemies. However, the small spatial scale of experiments such as ours and the inability to perfectly mimic all elements of climate change limit our ability to predict these longer term changes. A promising future direction is to combine experiments with study of natural phenological variation on landscape and larger scales.

DOI:10.1038/nature01333URLPMID:12511952 [本文引用: 1]

Over the past 100 years, the global average temperature has increased by approximately 0.6 degrees C and is projected to continue to rise at a rapid rate. Although species have responded to climatic changes throughout their evolutionary history, a primary concern for wild species and their ecosystems is this rapid rate of change. We gathered information on species and global warming from 143 studies for our meta-analyses. These analyses reveal a consistent temperature-related shift, or 'fingerprint', in species ranging from molluscs to mammals and from grasses to trees. Indeed, more than 80% of the species that show changes are shifting in the direction expected on the basis of known physiological constraints of species. Consequently, the balance of evidence from these studies strongly suggests that a significant impact of global warming is already discernible in animal and plant populations. The synergism of rapid temperature rise and other stresses, in particular habitat destruction, could easily disrupt the connectedness among species and lead to a reformulation of species communities, reflecting differential changes in species, and to numerous extirpations and possibly extinctions.

DOI:10.1002/1097-0088(20000630)20:83.0.CO;2-5URL [本文引用: 1]

Abstract Onset of the growing season in mid-latitudes is a period of rapid transition, which includes heightened interaction between living organisms and the lower atmosphere. Phenological events (seasonal plant and animal activity driven by environmental factors), such as first leaf appearance or flower bloom in plants, can serve as convenient markers to monitor the progression of this yearly shift, and assess longer-term change resulting from climate variations. We examined spring seasons across North America over the 1900–1997 period using modelled and actual lilac phenological data. Regional differences were detected, as well as an average 5–6 day advance toward earlier springs, over a 35-year period from 1959–1993 . Driven by seasonally warmer temperatures, this modification agrees with earlier bird nesting times, and corresponds to a comparable advance of spring plant phenology described in Europe. These results also align with trends towards longer growing seasons, reported by recent carbon dioxide and satellite studies. North American spring warming is strongest regionally in the northwest and northeast portions. Meanwhile, slight autumn cooling is apparent in the central USA. Copyright 08 2000 Royal Meteorological Society

DOI:10.1038/nature02121URLPMID:14712274 [本文引用: 1]

Climate change over the past ~30 years has produced numerous shifts in the distributions and abundances of species and has been implicated in one species-level extinction. Using projections of species' distributions for future climate scenarios, we assess extinction risks for sample regions that cover some 20% of the Earth's terrestrial surface. Exploring three approaches in which the estimated probability of extinction shows a power-law relationship with geographical range size, we predict, on the basis of mid-range climate-warming scenarios for 2050, that 15-37% of species in our sample of regions and taxa will be 0900committed to extinction0964. When the average of the three methods and two dispersal scenarios is taken, minimal climate-warming scenarios produce lower projections of species committed to extinction (~18%) than mid-range (~24%) and maximum-change (~35%) scenarios. These estimates show the importance of rapid implementation of technologies to decrease greenhouse gas emissions and strategies for carbon sequestration.

DOI:10.1073/pnas.94.5.1857URLPMID:11038606

Abstract Ecosystem processes are thought to depend on both the number and identity of the species present in an ecosystem, but mathematical theory predicting this has been lacking. Here we present three simple models of interspecific competitive interactions in communities containing various numbers of randomly chosen species. All three models predict that, on average, productivity increases asymptotically with the original biodiversity of a community. The two models that address plant nutrient competition also predict that ecosystem nutrient retention increases with biodiversity and that the effects of biodiversity on productivity and nutrient retention increase with interspecific differences in resource requirements. All three models show that both species identity and biodiversity simultaneously influence ecosystem functioning, but their relative importance varies greatly among the models. This theory reinforces recent experimental results and shows that effects of biodiversity on ecosystem functioning are predicted by well-known ecological processes.

[本文引用: 1]

Many alpine/arctic flowering plant species have presumably evolved the ability to self-pollinate as a reproductive assurance mechanism under harsh abiotic environmental conditions that restrict insect flower visitation. We compared self-pollination, pollen limitation, insect flower visitation, and dichogamy of low- and high-elevation populations of Cerastium alpinum, a species in established alpine communities, and Cerastium cerastoides, a pioneer species in disturbed habitats. Cerastium alpinum has large showy flowers, while C. cerastoides has smaller and paler flowers. The temporal separation of pollen release and stigma receptivity within a flower (dichogamy) was smallest in C. cerastoides, which was also more highly self-compatible. No pollen limitation on seed set occurred in any species, possibly due to their high selfing ability. Despite a substantially higher pollinator visitation to C. alpinum compared to C. cerastoides, the latter had the higher seed set. Pollen limitation, autogamy, and pollinator visitation did not differ between altitudes for either species. Differences in habitat and flower size, color, and development between the species are consistent with their different selfing ability.

DOI:10.1890/13-2235.1URL [本文引用: 2]

Abstract Understanding how flowering phenology responds to warming and cooling (i.e., symmetric or asymmetric response) is needed to predict the response of flowering phenology to future climate change that will happen with the occurrence of warm and cold years superimposed upon a long-term trend. A three-year reciprocal translocation experiment was performed along an elevation gradient from 3200 m to 3800 m in the Tibetan Plateau for six alpine plants. Transplanting to lower elevation (warming) advanced the first flowering date (FFD) and transplanting to higher elevation (cooling) had the opposite effect. The FFD of early spring flowering plants (ESF) was four times less sensitive to warming than to cooling (by 612.1 d/°C and 8.4 d/°C, respectively), while midsummer flowering plants (MSF) were about twice as sensitive to warming than to cooling (618.0 d/°C and 4.9 d/°C, respectively). Compared with pooled warming and cooling data, warming alone significantly underpredicted 3.1 d/°C for ESF and overestimated 1.7 d/°C for MSF. These results suggest that future empirical and experimental studies should consider nonlinear temperature responses that can cause such warming–cooling asymmetries as well as differing life strategies (ESF vs. MSF) among plant species.

DOI:10.1038/nature11014URLPMID:22622576 [本文引用: 1]

Abstract Warming experiments are increasingly relied on to estimate plant responses to global climate change. For experiments to provide meaningful predictions of future responses, they should reflect the empirical record of responses to temperature variability and recent warming, including advances in the timing of flowering and leafing. We compared phenology (the timing of recurring life history events) in observational studies and warming experiments spanning four continents and 1,634 plant species using a common measure of temperature sensitivity (change in days per degree Celsius). We show that warming experiments underpredict advances in the timing of flowering and leafing by 8.5-fold and 4.0-fold, respectively, compared with long-term observations. For species that were common to both study types, the experimental results did not match the observational data in sign or magnitude. The observational data also showed that species that flower earliest in the spring have the highest temperature sensitivities, but this trend was not reflected in the experimental data. These significant mismatches seem to be unrelated to the study length or to the degree of manipulated warming in experiments. The discrepancy between experiments and observations, however, could arise from complex interactions among multiple drivers in the observational data, or it could arise from remediable artefacts in the experiments that result in lower irradiance and drier soils, thus dampening the phenological responses to manipulated warming. Our results introduce uncertainty into ecosystem models that are informed solely by experiments and suggest that responses to climate change that are predicted using such models should be re-evaluated.

DOI:10.1080/17550874.2013.871654URL

Background: Alpine and arctic ecosystems at high latitudes have been shown to be particularly vulnerable to climate change, but little has been reported about plant community responses from lower latitudes, such as the vast Qinghai090009Tibetan Plateau.

A 250-year index of first flowering dates and its response to temperature changes

1

2010

... id="C5">物候被认为是气候变化的“指纹” (

Responses of tundra plants to experimental warming: Meta-analysis of the international tundra experiment

1999

Responses of spring phenology to climate change

1

2004

... id="C5">物候被认为是气候变化的“指纹” (

Spring phenology trends in Alberta, Canada: Links to ocean temperature

1

2000

... id="C5">物候被认为是气候变化的“指纹” (

Shifts in flowering phenology reshape a subalpine plant community

2

2014

... id="C21">增温改变了横断山区高山草甸珠芽拳参和银叶委陵菜的物候, 且同一物种不同物候阶段(花芽、开花、凋谢和果实成熟)对增温的响应方式(提前或推迟)和响应程度存在一定的差异, 甚至同一物候阶段内不同状态(开始、峰值和结束)对增温的响应都存在差异.同一物种的不同繁殖阶段对环境变化表现出不同的响应方式和敏感性,

... id="C22">Dorji等(2013)研究发现模拟增温对钉柱委陵菜(Potentilla saundersiana)的花芽起始期、开花起始期等物候指标不产生显著影响, 本研究通过银叶委陵菜和珠芽拳参的观测发现, 若仅采取与Dorji等(2013)相同的物候阶段作为响应温度变化的指标, 也可得到相同的结论, 认为模拟增温不改变两种植物的繁殖物候.但是若考虑整个繁殖序列, 则显示模拟增温显著延长了银叶委陵菜凋谢期长度、凋谢到成熟过渡期长度, 甚至显著缩短了开花到凋谢期长度.因此, 即使模拟增温对单个或几个物候阶段不产生显著影响, 也不能得出环境变化对该物种繁殖物候不产生影响的结论.同时Gugger等(2015)移位增温实验中, 以植物某一物候阶段的起始到下一物候阶段的峰值所经历的天数作为该阶段的持续时间, 结果显示增温显著缩短了植物凋谢期长度.本研究若仅使用凋谢期到成熟期过渡状态作为响应温度变化的指标, 则可以得出与Gugger (2015)类似的结论: 增温导致银叶委陵菜加速繁殖物候期; 但是若完整地记录银叶委陵菜整个繁殖物候期的长度,则显示增温延长了银叶委陵菜的繁殖物候期(p < 0.1), 单个的物候阶段与整个繁殖期对增温的响应呈现相反的结果, 植物繁殖物候某一阶段的响应与整个繁殖物候期的响应并不一致.因此, 在气候变化背景下对植物繁殖物候的研究中, 即使同一物种使用不同的物候指标也可能得到不同的结论, 甚至得出完全相反的结论, 单个物候阶段并不能准确地反映整个植物物候期对温度变化的响应(

Diverse responses of phenology to global changes in a grassland ecosystem

2

2006

... id="C5">物候被认为是气候变化的“指纹” (

... id="C23">不同物种对增温的响应方式(提前或推迟)和敏感程度存在一定差异.不同繁殖阶段对增温响应的差异还引起植物各物候阶段的持续时间、过渡时间以及繁殖周期发生了变化.Inouye (2008)发现在生长季会出现霜冻的地区, 霜冻会使得该地区提前开花植物的花遭受不同程度的损失, 因此植物会选择缩短繁殖期以提高繁殖成功率.Post等(2008)对3种植物的模拟增温研究中也发现, 增温后每种植物至少有一个繁殖阶段表现为加速.本研究发现增温后, 植物繁殖物候期表现为不变或延长.这可能是增温后不同的植物表现出不同的响应方式, 例如, Totland和Schulte-Herbrüggen (2003)研究发现增温4年并不改变卷耳属(Cerastium)植物开花的持续时间.Arft等(1999)的meta分析结果显示模拟增温2年后植物对增温的响应开始减弱, 本研究是在增温后的第5年开始观测记录繁殖物候, 因此无法判断物种繁殖物候在增温初期植物繁殖周期对增温的响应.同时, 植物繁殖物候特征对增温响应的种间差异, 可能是植物个体为避免对土壤中水分和养分利用效率竞争、营养生长期的过度重叠, 以及植物叶片对光照需求的竞争, 最大化利用资源的一种适应环境的结果(

近百年中国气候变化科学问题的新认识

1

2015

... id="C4">联合国政府间气候变化专门委员会(IPCC)第五次评估报告显示, 1901-2012年, 地球表面平均温度上升了0.89 ℃ (

近百年中国气候变化科学问题的新认识

1

2015

... id="C4">联合国政府间气候变化专门委员会(IPCC)第五次评估报告显示, 1901-2012年, 地球表面平均温度上升了0.89 ℃ (

Plant functional traits mediate reproductive phenology and success in response to experimental warming and snow addition in Tibet

2

2013

... id="C5">物候被认为是气候变化的“指纹” (

... id="C6">在全球变暖的背景下, 普遍认为高海拔和高纬度地区增温幅度更大(

Coexistence of similar species in a space-limited intertidal zone

1

1999

... id="C23">不同物种对增温的响应方式(提前或推迟)和敏感程度存在一定差异.不同繁殖阶段对增温响应的差异还引起植物各物候阶段的持续时间、过渡时间以及繁殖周期发生了变化.Inouye (2008)发现在生长季会出现霜冻的地区, 霜冻会使得该地区提前开花植物的花遭受不同程度的损失, 因此植物会选择缩短繁殖期以提高繁殖成功率.Post等(2008)对3种植物的模拟增温研究中也发现, 增温后每种植物至少有一个繁殖阶段表现为加速.本研究发现增温后, 植物繁殖物候期表现为不变或延长.这可能是增温后不同的植物表现出不同的响应方式, 例如, Totland和Schulte-Herbrüggen (2003)研究发现增温4年并不改变卷耳属(Cerastium)植物开花的持续时间.Arft等(1999)的meta分析结果显示模拟增温2年后植物对增温的响应开始减弱, 本研究是在增温后的第5年开始观测记录繁殖物候, 因此无法判断物种繁殖物候在增温初期植物繁殖周期对增温的响应.同时, 植物繁殖物候特征对增温响应的种间差异, 可能是植物个体为避免对土壤中水分和养分利用效率竞争、营养生长期的过度重叠, 以及植物叶片对光照需求的竞争, 最大化利用资源的一种适应环境的结果(

Toward a synthetic understanding of the role of phenology in ecology and evolution

1

2010

... id="C23">不同物种对增温的响应方式(提前或推迟)和敏感程度存在一定差异.不同繁殖阶段对增温响应的差异还引起植物各物候阶段的持续时间、过渡时间以及繁殖周期发生了变化.Inouye (2008)发现在生长季会出现霜冻的地区, 霜冻会使得该地区提前开花植物的花遭受不同程度的损失, 因此植物会选择缩短繁殖期以提高繁殖成功率.Post等(2008)对3种植物的模拟增温研究中也发现, 增温后每种植物至少有一个繁殖阶段表现为加速.本研究发现增温后, 植物繁殖物候期表现为不变或延长.这可能是增温后不同的植物表现出不同的响应方式, 例如, Totland和Schulte-Herbrüggen (2003)研究发现增温4年并不改变卷耳属(Cerastium)植物开花的持续时间.Arft等(1999)的meta分析结果显示模拟增温2年后植物对增温的响应开始减弱, 本研究是在增温后的第5年开始观测记录繁殖物候, 因此无法判断物种繁殖物候在增温初期植物繁殖周期对增温的响应.同时, 植物繁殖物候特征对增温响应的种间差异, 可能是植物个体为避免对土壤中水分和养分利用效率竞争、营养生长期的过度重叠, 以及植物叶片对光照需求的竞争, 最大化利用资源的一种适应环境的结果(

Lower plasticity exhibited by high-versus mid-elevation species in their phenological responses to manipulated temperature and drought

1

2015

... id="C5">物候被认为是气候变化的“指纹” (

Plant response to temperature in northern Alaska: Implications for predicting vegetation change

1

2005

... id="C5">物候被认为是气候变化的“指纹” (

Nonlinear flowering responses to climate: Are species approaching their limits of phenological change?

1

2013

... id="C5">物候被认为是气候变化的“指纹” (

Effects of climate change on phenology, frost damage, and floral abundance of montane wildflowers

2008

2

2013

... id="C4">联合国政府间气候变化专门委员会(IPCC)第五次评估报告显示, 1901-2012年, 地球表面平均温度上升了0.89 ℃ (

... id="C5">物候被认为是气候变化的“指纹” (

In situ mineralization of nitrogen and phosphorus of arctic soils after perturbations simulating climate change

1

1993

... id="C6">在全球变暖的背景下, 普遍认为高海拔和高纬度地区增温幅度更大(

Experimental warming causes large and rapid species loss, dampened by simulated grazing, on the Tibetan Plateau

1

2004

... id="C4">联合国政府间气候变化专门委员会(IPCC)第五次评估报告显示, 1901-2012年, 地球表面平均温度上升了0.89 ℃ (

我国横断山区1960-2008年气温和降水时空变化特征

1

2010

... id="C6">在全球变暖的背景下, 普遍认为高海拔和高纬度地区增温幅度更大(

我国横断山区1960-2008年气温和降水时空变化特征

1

2010

... id="C6">在全球变暖的背景下, 普遍认为高海拔和高纬度地区增温幅度更大(

Shifting phenology and abundance under experimental warming alters trophic relationships and plant reproductive capacity

1

2011

... id="C23">不同物种对增温的响应方式(提前或推迟)和敏感程度存在一定差异.不同繁殖阶段对增温响应的差异还引起植物各物候阶段的持续时间、过渡时间以及繁殖周期发生了变化.Inouye (2008)发现在生长季会出现霜冻的地区, 霜冻会使得该地区提前开花植物的花遭受不同程度的损失, 因此植物会选择缩短繁殖期以提高繁殖成功率.Post等(2008)对3种植物的模拟增温研究中也发现, 增温后每种植物至少有一个繁殖阶段表现为加速.本研究发现增温后, 植物繁殖物候期表现为不变或延长.这可能是增温后不同的植物表现出不同的响应方式, 例如, Totland和Schulte-Herbrüggen (2003)研究发现增温4年并不改变卷耳属(Cerastium)植物开花的持续时间.Arft等(1999)的meta分析结果显示模拟增温2年后植物对增温的响应开始减弱, 本研究是在增温后的第5年开始观测记录繁殖物候, 因此无法判断物种繁殖物候在增温初期植物繁殖周期对增温的响应.同时, 植物繁殖物候特征对增温响应的种间差异, 可能是植物个体为避免对土壤中水分和养分利用效率竞争、营养生长期的过度重叠, 以及植物叶片对光照需求的竞争, 最大化利用资源的一种适应环境的结果(

Global warming and the disruption of plant-pollinator interactions

1

2007

... id="C22">Dorji等(2013)研究发现模拟增温对钉柱委陵菜(Potentilla saundersiana)的花芽起始期、开花起始期等物候指标不产生显著影响, 本研究通过银叶委陵菜和珠芽拳参的观测发现, 若仅采取与Dorji等(2013)相同的物候阶段作为响应温度变化的指标, 也可得到相同的结论, 认为模拟增温不改变两种植物的繁殖物候.但是若考虑整个繁殖序列, 则显示模拟增温显著延长了银叶委陵菜凋谢期长度、凋谢到成熟过渡期长度, 甚至显著缩短了开花到凋谢期长度.因此, 即使模拟增温对单个或几个物候阶段不产生显著影响, 也不能得出环境变化对该物种繁殖物候不产生影响的结论.同时Gugger等(2015)移位增温实验中, 以植物某一物候阶段的起始到下一物候阶段的峰值所经历的天数作为该阶段的持续时间, 结果显示增温显著缩短了植物凋谢期长度.本研究若仅使用凋谢期到成熟期过渡状态作为响应温度变化的指标, 则可以得出与Gugger (2015)类似的结论: 增温导致银叶委陵菜加速繁殖物候期; 但是若完整地记录银叶委陵菜整个繁殖物候期的长度,则显示增温延长了银叶委陵菜的繁殖物候期(p < 0.1), 单个的物候阶段与整个繁殖期对增温的响应呈现相反的结果, 植物繁殖物候某一阶段的响应与整个繁殖物候期的响应并不一致.因此, 在气候变化背景下对植物繁殖物候的研究中, 即使同一物种使用不同的物候指标也可能得到不同的结论, 甚至得出完全相反的结论, 单个物候阶段并不能准确地反映整个植物物候期对温度变化的响应(

Changes in phenological sequences of alpine communities across a natural elevation gradient

1

2016

... id="C5">物候被认为是气候变化的“指纹” (

European phenological response to climate change matches the warming pattern

1

2006

... id="C5">物候被认为是气候变化的“指纹” (

Responses to a warming world

1

2001

... id="C23">不同物种对增温的响应方式(提前或推迟)和敏感程度存在一定差异.不同繁殖阶段对增温响应的差异还引起植物各物候阶段的持续时间、过渡时间以及繁殖周期发生了变化.Inouye (2008)发现在生长季会出现霜冻的地区, 霜冻会使得该地区提前开花植物的花遭受不同程度的损失, 因此植物会选择缩短繁殖期以提高繁殖成功率.Post等(2008)对3种植物的模拟增温研究中也发现, 增温后每种植物至少有一个繁殖阶段表现为加速.本研究发现增温后, 植物繁殖物候期表现为不变或延长.这可能是增温后不同的植物表现出不同的响应方式, 例如, Totland和Schulte-Herbrüggen (2003)研究发现增温4年并不改变卷耳属(Cerastium)植物开花的持续时间.Arft等(1999)的meta分析结果显示模拟增温2年后植物对增温的响应开始减弱, 本研究是在增温后的第5年开始观测记录繁殖物候, 因此无法判断物种繁殖物候在增温初期植物繁殖周期对增温的响应.同时, 植物繁殖物候特征对增温响应的种间差异, 可能是植物个体为避免对土壤中水分和养分利用效率竞争、营养生长期的过度重叠, 以及植物叶片对光照需求的竞争, 最大化利用资源的一种适应环境的结果(

Phenology feedbacks on climate change

1

2009

... id="C23">不同物种对增温的响应方式(提前或推迟)和敏感程度存在一定差异.不同繁殖阶段对增温响应的差异还引起植物各物候阶段的持续时间、过渡时间以及繁殖周期发生了变化.Inouye (2008)发现在生长季会出现霜冻的地区, 霜冻会使得该地区提前开花植物的花遭受不同程度的损失, 因此植物会选择缩短繁殖期以提高繁殖成功率.Post等(2008)对3种植物的模拟增温研究中也发现, 增温后每种植物至少有一个繁殖阶段表现为加速.本研究发现增温后, 植物繁殖物候期表现为不变或延长.这可能是增温后不同的植物表现出不同的响应方式, 例如, Totland和Schulte-Herbrüggen (2003)研究发现增温4年并不改变卷耳属(Cerastium)植物开花的持续时间.Arft等(1999)的meta分析结果显示模拟增温2年后植物对增温的响应开始减弱, 本研究是在增温后的第5年开始观测记录繁殖物候, 因此无法判断物种繁殖物候在增温初期植物繁殖周期对增温的响应.同时, 植物繁殖物候特征对增温响应的种间差异, 可能是植物个体为避免对土壤中水分和养分利用效率竞争、营养生长期的过度重叠, 以及植物叶片对光照需求的竞争, 最大化利用资源的一种适应环境的结果(

Changed plant and animal life cycles from 1952 to 2000 in the Mediterranean region

1

2002

... id="C6">在全球变暖的背景下, 普遍认为高海拔和高纬度地区增温幅度更大(

Elevation-dependent warming in mountain regions of the world

3

2015

... id="C5">物候被认为是气候变化的“指纹” (

... ), 繁殖物候期总的长度也未发生明显变化(

... ), 即增温虽然能够提前繁殖物候的各个阶段, 并不改变植物繁殖的速率.这些矛盾的繁殖物候的研究都是使用单个的发育阶段作为评估物候对气候变化响应的指标, 而植物发育是一个连续的过程, 早期的发育阶段会对后期的发育阶段产生一定的限制作用(

Phenological sequences reveal aggregate life history response to climatic warming

2

2008

... id="C5">物候被认为是气候变化的“指纹” (

... id="C23">不同物种对增温的响应方式(提前或推迟)和敏感程度存在一定差异.不同繁殖阶段对增温响应的差异还引起植物各物候阶段的持续时间、过渡时间以及繁殖周期发生了变化.Inouye (2008)发现在生长季会出现霜冻的地区, 霜冻会使得该地区提前开花植物的花遭受不同程度的损失, 因此植物会选择缩短繁殖期以提高繁殖成功率.Post等(2008)对3种植物的模拟增温研究中也发现, 增温后每种植物至少有一个繁殖阶段表现为加速.本研究发现增温后, 植物繁殖物候期表现为不变或延长.这可能是增温后不同的植物表现出不同的响应方式, 例如, Totland和Schulte-Herbrüggen (2003)研究发现增温4年并不改变卷耳属(Cerastium)植物开花的持续时间.Arft等(1999)的meta分析结果显示模拟增温2年后植物对增温的响应开始减弱, 本研究是在增温后的第5年开始观测记录繁殖物候, 因此无法判断物种繁殖物候在增温初期植物繁殖周期对增温的响应.同时, 植物繁殖物候特征对增温响应的种间差异, 可能是植物个体为避免对土壤中水分和养分利用效率竞争、营养生长期的过度重叠, 以及植物叶片对光照需求的竞争, 最大化利用资源的一种适应环境的结果(

Effects of experimental warming on plant reproductive phenology in a subalpine meadow

1

1998

... id="C5">物候被认为是气候变化的“指纹” (

Fingerprints of global warming on wild animals and plants

1

2003

... id="C5">物候被认为是气候变化的“指纹” (

Changes in North American spring

1

2000

... id="C6">在全球变暖的背景下, 普遍认为高海拔和高纬度地区增温幅度更大(

Extinction risk from climate change

1

2004

... id="C23">不同物种对增温的响应方式(提前或推迟)和敏感程度存在一定差异.不同繁殖阶段对增温响应的差异还引起植物各物候阶段的持续时间、过渡时间以及繁殖周期发生了变化.Inouye (2008)发现在生长季会出现霜冻的地区, 霜冻会使得该地区提前开花植物的花遭受不同程度的损失, 因此植物会选择缩短繁殖期以提高繁殖成功率.Post等(2008)对3种植物的模拟增温研究中也发现, 增温后每种植物至少有一个繁殖阶段表现为加速.本研究发现增温后, 植物繁殖物候期表现为不变或延长.这可能是增温后不同的植物表现出不同的响应方式, 例如, Totland和Schulte-Herbrüggen (2003)研究发现增温4年并不改变卷耳属(Cerastium)植物开花的持续时间.Arft等(1999)的meta分析结果显示模拟增温2年后植物对增温的响应开始减弱, 本研究是在增温后的第5年开始观测记录繁殖物候, 因此无法判断物种繁殖物候在增温初期植物繁殖周期对增温的响应.同时, 植物繁殖物候特征对增温响应的种间差异, 可能是植物个体为避免对土壤中水分和养分利用效率竞争、营养生长期的过度重叠, 以及植物叶片对光照需求的竞争, 最大化利用资源的一种适应环境的结果(

Plant diversity and ecosystem productivity: Theoretical considerations

1997

Breeding system, insect flower visitation, and floral traits of two alpine Cerastium species in Norway

1

2003

... id="C5">物候被认为是气候变化的“指纹” (

Asymmetric sensitivity of first flowering date to warming and cooling in alpine plants

2

2014

... id="C5">物候被认为是气候变化的“指纹” (

... ), 甚至可能影响后期阶段对气候变化的响应.因此, 使用单个的物候阶段作为观测指标并不能准确地反映植物物候对气候变化的响应(

Warming experiments under predict plant phenological responses to climate change

1

2012

... id="C6">在全球变暖的背景下, 普遍认为高海拔和高纬度地区增温幅度更大(

Plant community responses to five years of simulated climate warming in an alpine fen of the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau

2015