HTML

--> --> -->Because warm-season heavy rainfall can develop and dissipate rapidly within a day (Gray and Jacobson, 1977; Jung et al., 2001; Zhang and Chen, 2016; Zeng et al., 2019), identification of the characteristics of the diurnal variations in summertime heavy rainfall is important. Previous studies based on satellite and ground observations and numerical experiments have demonstrated that the peak time of heavy rainfall is generally related to the summer monsoon frontal system over East Asia (e.g., Wang et al., 2005; Geng and Yamada, 2007; Yuan et al., 2010; Chen et al., 2017; Xue et al., 2018; Zeng et al., 2019; Wu et al., 2020). Recently, it has been found that a nocturnal low-level jet transporting moisture northward plays a crucial role in causing the morning peak of the heavy rainfall in China by intensifying the mesoscale convective systems in the mei-yu frontal rainband overnight (Chen et al., 2017; Zeng et al., 2019). In addition, over the oceanic areas of East Asia, the morning peak of heavy rainfall is related to the low storm-top height and abundant water content characteristic of the humid monsoon environment [“the warm-type heavy rainfall mechanism” (Sohn et al., 2013; Song and Sohn, 2015)]. Apart from the morning peak, a double peak comprising both the morning and afternoon and one comprising just the afternoon are also found for the heavy rainfall in some regions in East Asia. These are related to the location relative to the monsoon frontal zone and the different topographic and environmental characteristics (e.g., Geng and Yamada, 2007; He and Zhang, 2010; Yuan et al., 2012; Xue et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2020). For example, heavy rainfalls in inland areas of East Asia show the afternoon peak and are related to the high storm-top heights of deep continental convection with abundant water/ice contents [“the cold-type heavy rainfall mechanism” (Song and Sohn, 2015; Yu et al., 2007; Park et al., 2016)].

It is known that the warm-type heavy rainfall mechanism prevails in Korea (Song et al., 2017, 2019; Park et al., 2018; Song and Sohn, 2020). However, the peak time of heavy rainfall varies from the morning to afternoon according to years and specific regions in Korea (Lim and Kwon, 1998; Hyun et al., 2010; Roh et al., 2012; Jo et al., 2020). Hence, the diurnal characteristics of summertime heavy rainfall in Korea can be diverse and cannot be represented by a single type of diurnal variation or mechanism.

The present study investigates diverse characteristics of diurnal variations in summertime heavy rainfall in Korea and associated synoptic and mesoscale circulations. We particularly focus on the period of July as it is climatologically the wettest month in Korea (Ho and Kang, 1988; Ho et al., 2003). We also considered the fact that the occurrence of heavy rainfall events in Korea generally peak in July (Jo et al., 2020). Based on the analyzed results, we examine whether the heavy rainfall events in the 2020 summer is significantly different from heavy rainfall events in other years. This paper is organized as follows: datasets and methodologies used in this study are described in section 2, the results are presented in section 3, and a summary of this study and discussion of the results appears in section 4.

2.1. Observation and reanalysis data

The hourly precipitation data from 1980?2020 at 63 Korean Meteorological Administration (KMA) stations were analyzed. We excluded precipitation events during tropical cyclones using the KMA record. To investigate the synoptic/mesoscale circulations, winds, pressure-based vertical velocity, air temperatures, specific humidity, relative humidity, cloud liquid/ice water contents, and geopotential heights from 900 hPa to 200 hPa were collected from the monthly and hourly Modern-Era Retrospective Analysis for the Research and Applications version 2 dataset (MERRA-2; Gelaro et al., 2017). The grid resolution of the monthly (hourly) dataset is 1.25° longitude × 0.625° latitude (0.625° longitude × 0.5° latitude). Gelaro et al. (2017) described that the bias of water cycle representation, particularly the extereme values, in the MERRA-2 is reduced compared to the previous version of MERRA. However, it is important to appreciate that the cloud liquid/ice water contents are model dependent, and relevant analysis here is only intended to better understand the relations implied behind various physical entities, rather then representing the values themselves.2

2.2. Classification of two heavy rainfall types

To identify the general types of summertime heavy rainfall in Korea within the perspectives of climatology, we applied the KMA heavy rainfall criteria, namely, 12-hour accumulated rainfall of 110 mm or more, to the accumulated hourly precipitation data in July that was calculated using the mean precipitation for 63 stations in Korea. According to this criterion, if the accumulated rainfall between 0000?1200 or 1200?2400 LST (LST = UTC + 9) exceeded 110 mm, we defined that as the morning and afternoon heavy rainfall type, respectively. Table 1 shows the years when both heavy rainfall types occurred in Korea. The two major types are identified as morning only heavy rainfall (MO) and all-day heavy rainfall (AD); the AD-type satisfies the KMA criteria not only in the morning but also in the afternoon. The years excluded in Table 1 (i.e., 1984, 1992, 1994, 1996, 2000, 2002, 2008, 2014, 2015, 2018, and 2019) could not meet the KMA criteria. Note that the 2020 heavy rainfall case is in the AD-type.| Type | Year |

| MO | 1980, 1982, 1990, 1993, 1995, 1999, 2004, 2005, 2007, 2012, 2013, 2017 |

| AD | 1981, 1985, 1986, 1987, 1988, 1989, 1991, 1997, 1998, 2001, 2003, 2006, 2009, 2010, 2011, 2016, 2020 |

| Note: 1983: the year of July heavy rainfall for 1200?2400 LST. | |

Table1. Years of two types of heavy rainfall (≥110 mm in 12 h) in the morning (0000?1200 LST; MO) and all-day (both 0000?1200 and 1200?2400 LST; AD) for 1980?2020.

3.1. Diurnal characteristics and associated synoptic/mesoscale features of the heavy rainfall

Morning peaks are prevalent for both MO- and AD-types (Fig. 1) in the precipitation diurnal cycles. This reconfirms the results found in previous studies (Sohn et al., 2013; Song et al., 2019). The AD-type tends to produce more precipitation than the MO-type during both the morning and afternoon hours (Fig. 1c). This suggests that the AD-type involves larger amounts of atmospheric moisture than the MO-type. Note that the diurnal cycle in the 2020 case shows two distinct peaks, one in the morning and another in the afternoon (Fig. 1b). When we examined diurnal cycles of precipitation for each year (not shown), this pattern in 2020 is similar to the one observed in 1991 only (Fig. 1b); however, the amount of precipitation during the morning and afternoon in the 2020 case exceeds the 75th percentile of the AD-type while that in the 1991 case was in the interquartile range (Fig. 1c). Figure1. Diurnal cycle of hourly precipitation (mm h?1) for (a) MO-type and (b) AD-type. The years for MO- and AD-types are listed in Table 1. (c) Ranges of the 12-h precipitation in 0000?1200 and 1200?2400 LST for the two rainfall types. Thick lines and shading in (a, b) indicate the composite average and the ranges within ±1 standard deviation every hour, respectively, for two years (2020 and 1991), depicted by red and black lines, respectively.

Figure1. Diurnal cycle of hourly precipitation (mm h?1) for (a) MO-type and (b) AD-type. The years for MO- and AD-types are listed in Table 1. (c) Ranges of the 12-h precipitation in 0000?1200 and 1200?2400 LST for the two rainfall types. Thick lines and shading in (a, b) indicate the composite average and the ranges within ±1 standard deviation every hour, respectively, for two years (2020 and 1991), depicted by red and black lines, respectively.To investigate the associated synoptic circulations for the two heavy rainfall types, we averaged the anomalies of the 850-hPa geopotential heights, winds, moisture divergence, and moisture fluxes in July for each of heavy rainfall types based on the monthly MERRA-2 data (Fig. 2). Compared to the climatological pattern (Fig. 2a), the anomalous circulation patterns of both types generally show enhanced summer monsoon circulations; however, significant differences were found between them. The western North Pacific subtropical high (WNPSH) is strengthened (weakened) near the East China Sea and Philippine Sea (the Korean Peninsula, Japan, and east of Japan) for the MO-type (Fig. 2b). This westward-expanded WNPSH induces anomalous westerly winds from eastern China to Korea. However, the intensified WNPSH over the entire western North Pacific region is found for the AD-type (Fig. 2c). Along the edge of the intensified WNPSH, the southwesterly wind anomaly blows from the East China Sea to Korea. The anomalous moisture circulation corresponded well with the anomalous lower-level atmospheric patterns (Figs. 2d?2f). For the MO-type, although westerly moisture flux is found over the Yellow Sea, moisture convergence was confined to the coast of eastern China (Fig. 2e). Meanwhile, for the AD-type, the southwesterly moisture flux brings relatively humid air from the lower latitudes to Korea, which results in strong moisture convergence along the latitude Korea (Fig. 2f). This indicates a much more humid condition in Korea for the AD-type than for the MO-type.

Figure2. Composite fields of anomalies in July for (a?c) geopotential height [contours (m); positive: solid line, negative: dashed line] and horizontal wind (vector; m s?1), (d?f) moisture divergence (shading; kg kg?1 10?8 s?1) and flux (vector; kg kg?1 m s?1) at 850 hPa. (a, d) represents climatology, (b, e) MO-type, and (e, f) AD-type. Magnitudes of wind, moisture divergence, and moisture flux anomalies are plotted only when the grid values are at the 90% confidence level. The cyan contour represents the statistical significance at the 90% confidence level.

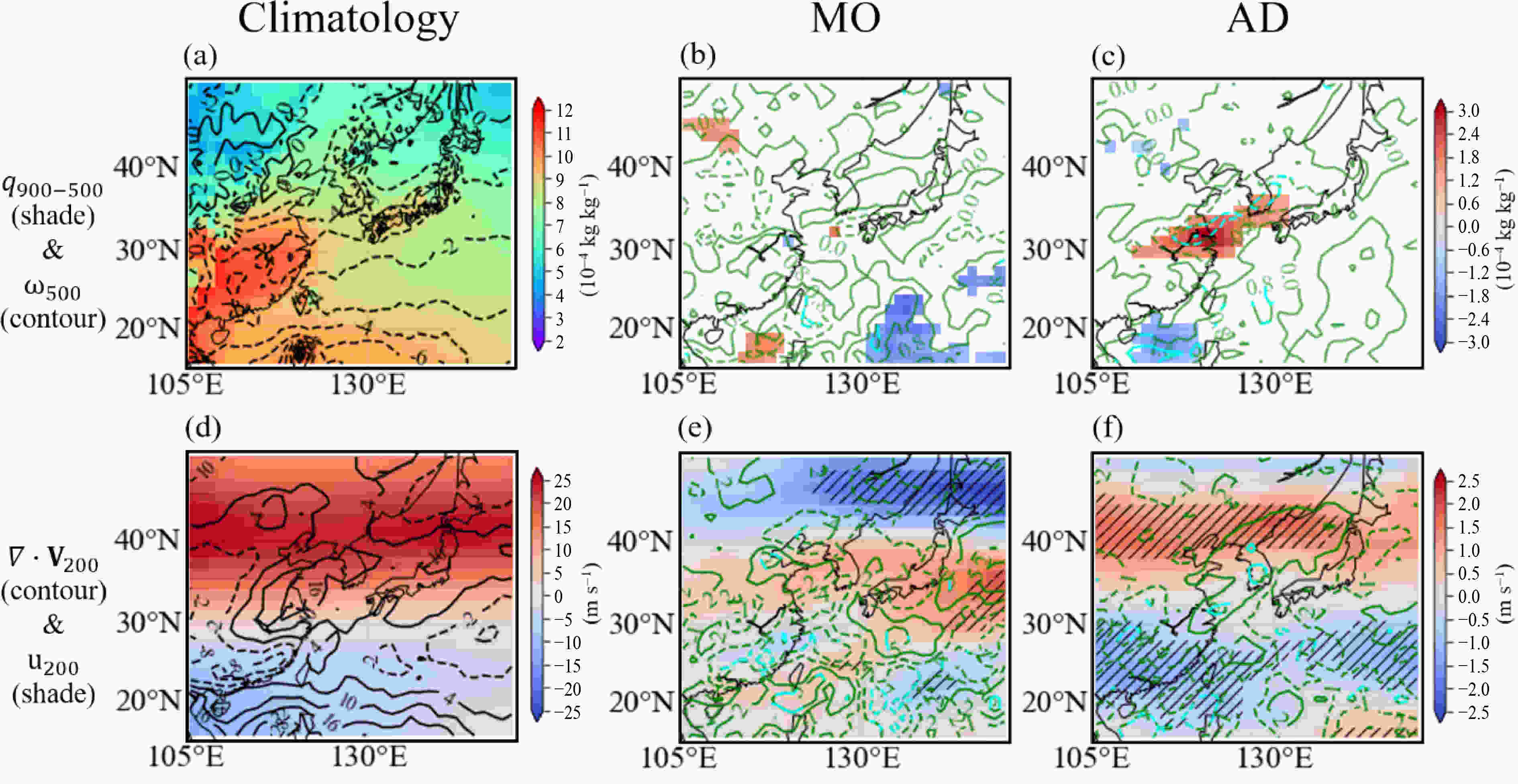

Figure2. Composite fields of anomalies in July for (a?c) geopotential height [contours (m); positive: solid line, negative: dashed line] and horizontal wind (vector; m s?1), (d?f) moisture divergence (shading; kg kg?1 10?8 s?1) and flux (vector; kg kg?1 m s?1) at 850 hPa. (a, d) represents climatology, (b, e) MO-type, and (e, f) AD-type. Magnitudes of wind, moisture divergence, and moisture flux anomalies are plotted only when the grid values are at the 90% confidence level. The cyan contour represents the statistical significance at the 90% confidence level.Figure 3 depicts the anomalies in the vertically integrated specific humidity at 900?500 hPa, 500-hPa vertical velocity, 200-hPa divergence, and 200-hPa zonal winds. For the AD-type, a considerable increase in humidity near Korea is observed resulting from the moisture circulations (Fig. 3c). In addition, a significant upward motion anomaly in southern Korea is also identified as a negative 500-hPa vertical velocity anomaly (Fig. 3c) which is induced by the upper-tropospheric circulation (Figs. 3d?3f). The enhanced upper-tropospheric jet and related divergence anomaly over the Korean Peninsula could induce strong rising motions over Korea (Fig. 3f). These synoptic features related to the AD-type appear to consistently induce heavy rainfall through the day, from morning to afternoon. For the MO-type, some changes in the specific humidity, vertical velocity, and upper-tropospheric jet and divergence are also found over Korea. However, their statistical significance is below the 90% confidence level (Figs. 3b and 3e), indicating that the anomalous synoptic circulation for the MO-type is not significantly different from the climatological circulation (Figs. 3a and 3d).

Figure3. Same as Fig. 2 except for (a?c) vertically integrated specific humidity in the 900?500 hPa layer (shading; 10?4 kg kg?1) and 500-hPa vertical velocity (contours, 10?2 Pa s?1; positive: solid line, negative: dashed line) and (d?f) divergence (contours, 10?7 s?1; positive: solid line, negative: dashed line) and zonal wind (shading; m s?1) at 200 hPa. The diagonal lines represent areas in which the statistical significance exceeds the 90% confidence level.

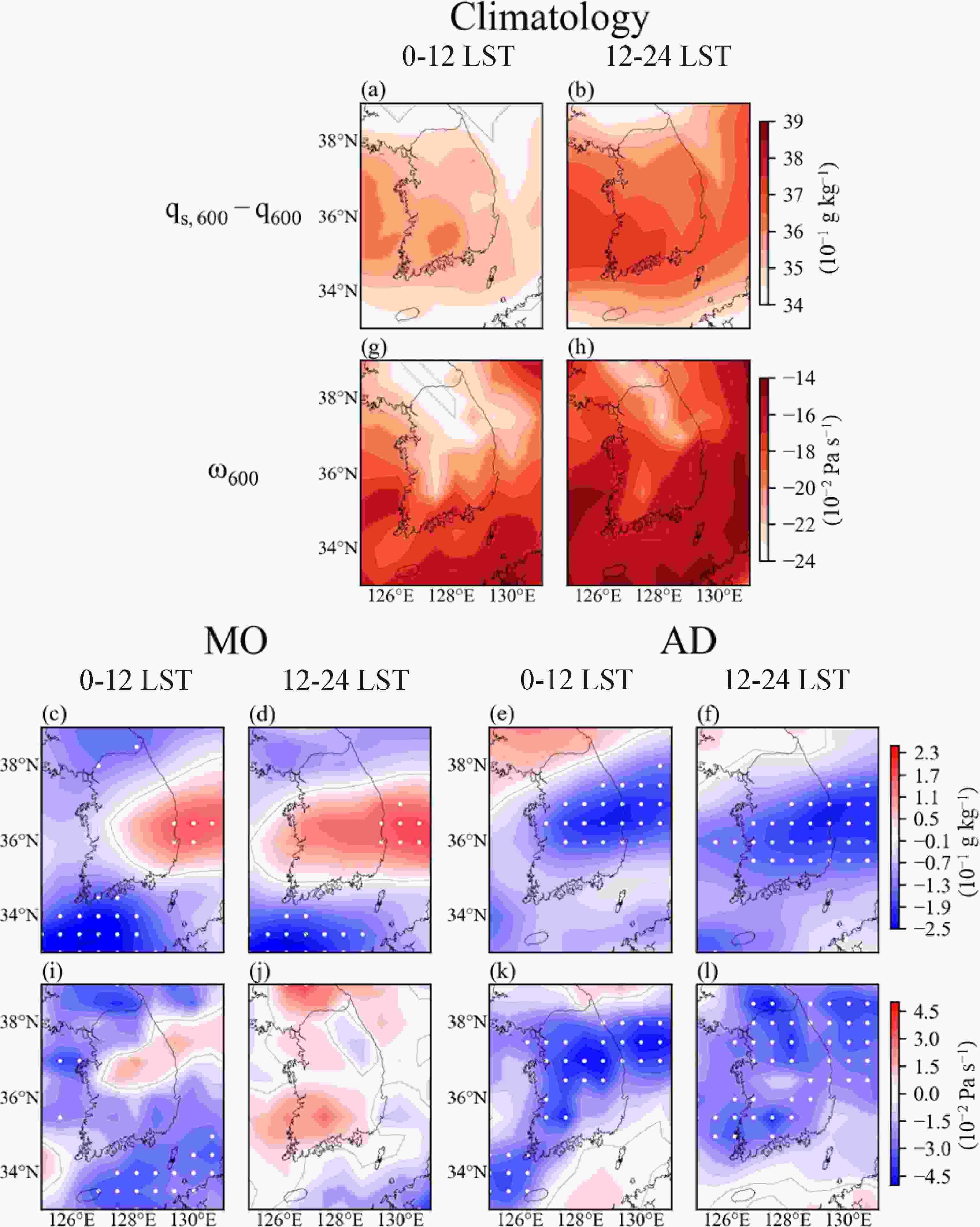

Figure3. Same as Fig. 2 except for (a?c) vertically integrated specific humidity in the 900?500 hPa layer (shading; 10?4 kg kg?1) and 500-hPa vertical velocity (contours, 10?2 Pa s?1; positive: solid line, negative: dashed line) and (d?f) divergence (contours, 10?7 s?1; positive: solid line, negative: dashed line) and zonal wind (shading; m s?1) at 200 hPa. The diagonal lines represent areas in which the statistical significance exceeds the 90% confidence level.Although it is found that the overall synoptic circulation provides a favorable environment for the heavy rainfall for both the AD-type and the MO-type, detailed environmental mechanisms assoicated with the diurnal variations of heavy rainfall for the two types is not easily understood based on the results of synoptic analysis alone. Thus, further analysis was performed on the differences in the mesoscale features between the morning (0000–1200 LST) and afternoon (1200–2400 LST) rainfall peaks using the hourly MERRA-2 data (Fig. 4). According to the climatology results, the mid-tropospheric saturation deficit is smaller (Figs. 4a and 4b) and mid-tropospheric upward mass flux is larger (Figs. 4g and 4h) in the morning than in the afternoon. These results indicate that morning heavy rainfall is climatologically favored over Korea. The mesoscale features of the MO-type are not significantly different from the climatology in either the morning or afternoon rainfall peaks except for those near the southern and eastern ocean regions around Korea. However, it is noteworthy that these two mesoscale features of the MO-type are different between morning and afternoon because smaller saturation deficit anomalies (Figs. 4c and 4d) and negative upward mass flux anomalies (Figs. 4i and 4j) are observed in the morning when the precipitation amount is larger (Figs. 1a and 1c). For the AD-type, however, overall mesoscale features both in the morning and afternoon present significantly more favorable conditions for precipitation than the climatology. Less moisture deficit (Figs. 4e and 4f) and larger upward mass flux (Figs. 4k and 4l) imply that mesoscale conditions in the AD-type are more favorable for high precipitation (> 110 mm in 12 h) both in the morning and afternoon than the climatology of each.

Figure4. Composite fields of (a–f) mid-tropospheric saturation deficit at 600 hPa (10?1 g kg?1) and (g–l) mid-tropospheric upward mass flux at 600 hPa (10?2 Pa s?1) for climatology, MO-type, and AD-type at 0000–1200 and 1200–2400 LST. White dots indicate where the statistical significance exceeds the 90% confidence level.

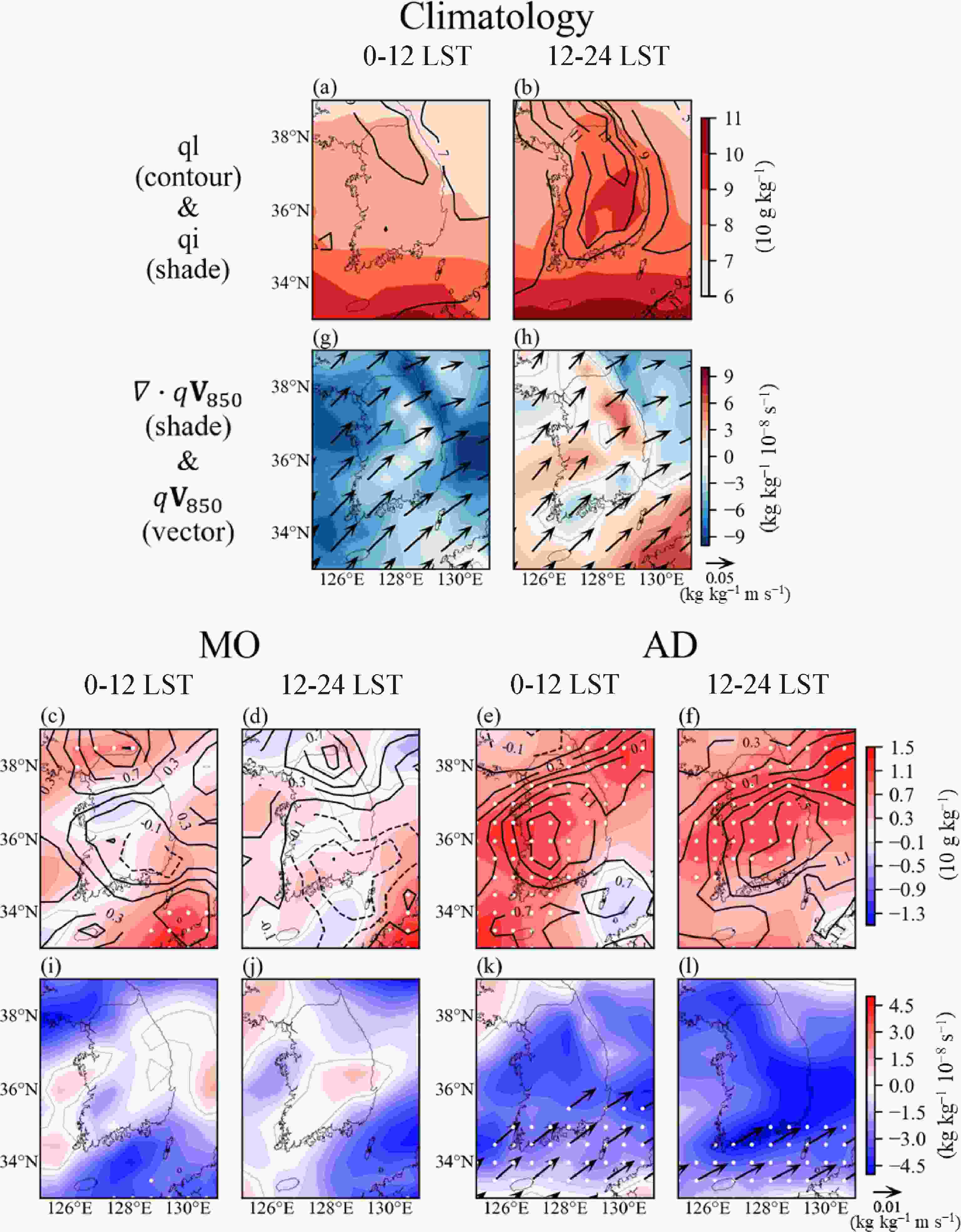

Figure4. Composite fields of (a–f) mid-tropospheric saturation deficit at 600 hPa (10?1 g kg?1) and (g–l) mid-tropospheric upward mass flux at 600 hPa (10?2 Pa s?1) for climatology, MO-type, and AD-type at 0000–1200 and 1200–2400 LST. White dots indicate where the statistical significance exceeds the 90% confidence level.Figure 5 presents the vertically-integrated mass fraction of liquid and ice cloud water in the 900?200 hPa layer as well as the moisture divergence and flux at 850 hPa. According to the climatology results, the mass fraction of the liquid and ice cloud water is smaller in the morning than in the afternoon (Figs. 5a and 5b). For the MO-type (Figs. 5c and 5d), the deviation from the climatology is insignificant. For the AD-type (Figs. 5e and 5f), the mass fraction of both liquid and ice cloud water are significantly larger than in the climatology both in the morning and the afternoon despite the heavy rainfall. This is consistent with the moisture divergence and flux at 850 hPa shown in Figs. 5g–5l. The climatology shows clearly convergence of moisture at 850 hPa in the morning (Fig. 5g), while the divergence of moisture at 850 hPa is seen in the afternoon (Fig. 5h). The overall moisture flux occurs under a southwesterly flow. The moisture divgerence and flux for MO-type (Figs. 5i and 5j) are not significantly different from the climatological values in the morning and the afternoon. For AD-type, however, moisture convergence (Figs. 5k and 5l) is significantly larger than the climatology with attendant southwesterly anomalies of moisture flux. Abundant moisture flux from the southwestern part of Korea and their convergence over the southern part of Korea supports heavy rainfall both in the morning and the afternoon in AD-types.

Figure5. Same as Fig. 4, but for (a–f) vertically integrated cloud liquid water (contours, 10 g kg?1; positive: solid line, negative: dashed line) and cloud ice water (shading; 10 g kg?1) for 900–200 hPa and (g–l) moisture divergence (shading; 10?8 kg kg?1 s?1) and flux (vectors; kg kg?1 m s?1) at 850 hPa. White dots indicate where the statistical significance exceeded the 90% confidence level. The arrows in panel (i, j, k, and l) are only plotted when the grid values are at the 90% confidence level.

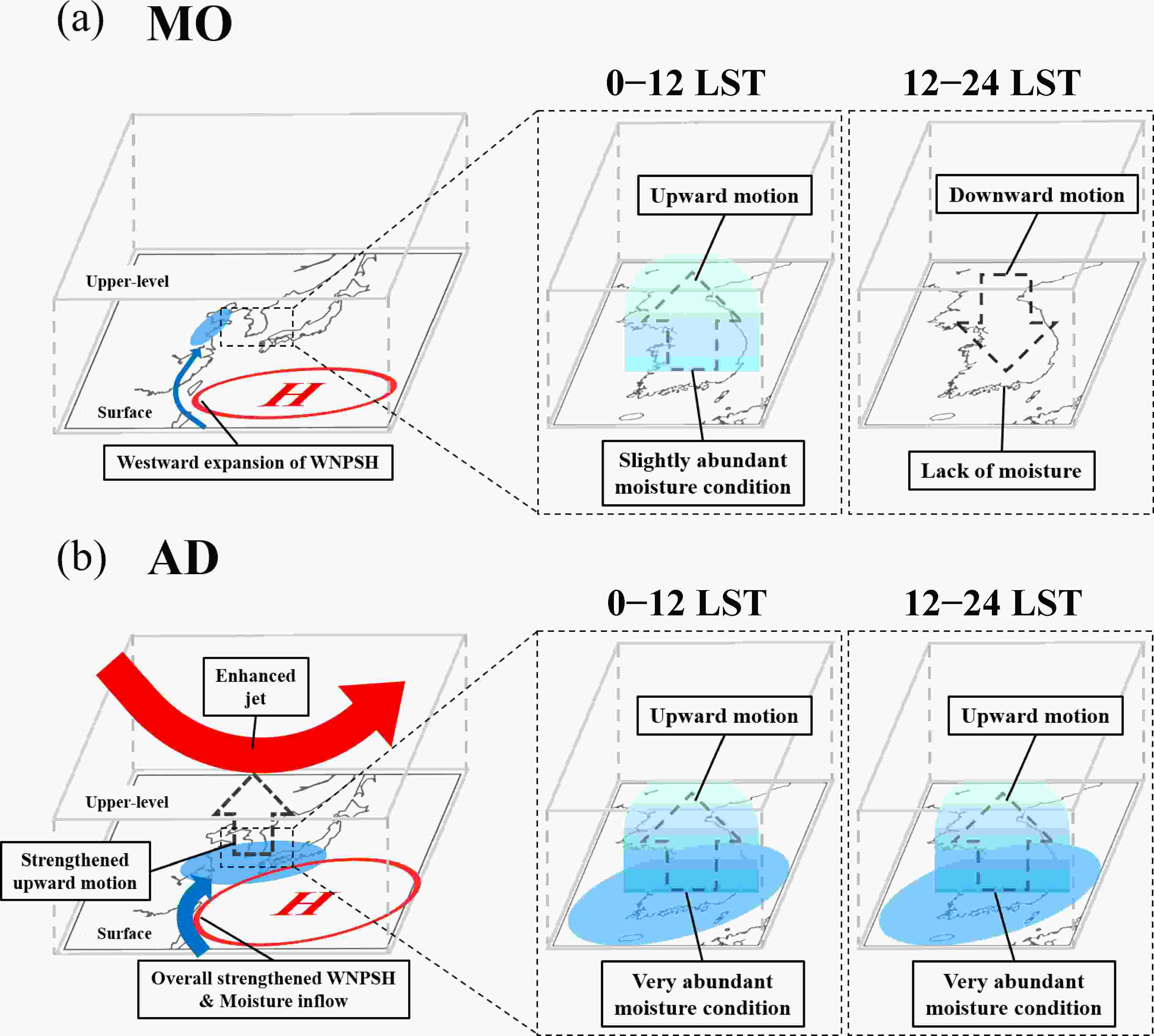

Figure5. Same as Fig. 4, but for (a–f) vertically integrated cloud liquid water (contours, 10 g kg?1; positive: solid line, negative: dashed line) and cloud ice water (shading; 10 g kg?1) for 900–200 hPa and (g–l) moisture divergence (shading; 10?8 kg kg?1 s?1) and flux (vectors; kg kg?1 m s?1) at 850 hPa. White dots indicate where the statistical significance exceeded the 90% confidence level. The arrows in panel (i, j, k, and l) are only plotted when the grid values are at the 90% confidence level.Figure 6 summarizes the results. The anomalous atmospheric circulations for the MO-type generally correspond to the climatological pattern except for the westward expansion of WNPSH (Fig. 6a). For the AD-type (Fig. 6b), the anomalous moisture inflow from low latitudes into Korea by the strengthened WNPSH generates abundant moisture. The strong upward motion anomaly due to the enhanced upper-tropospheric jet promotes the formation of heavy rainfall in Korea under humid conditions. When the morning and afternoon conditions are further examined, the mesoscale features in the afternoon clearly diverges into the two types; meanwhile, those in the morning are nearly the same except for the moisture content. For the MO-type, overall features in the morning and the afternoon are similar to the climatology; however, favorable mesoscale conditions for heavy rainfall are dominant in the morning. For the AD-type of heavy rainfall, abundant moisture content and strong upward mass flux are observed throughout the day.

Figure6. Schematic models for anomalous atmospheric circulations related to MO- and AD-types.

Figure6. Schematic models for anomalous atmospheric circulations related to MO- and AD-types.2

3.2. Heavy rainfall features in the 1991 and 2020

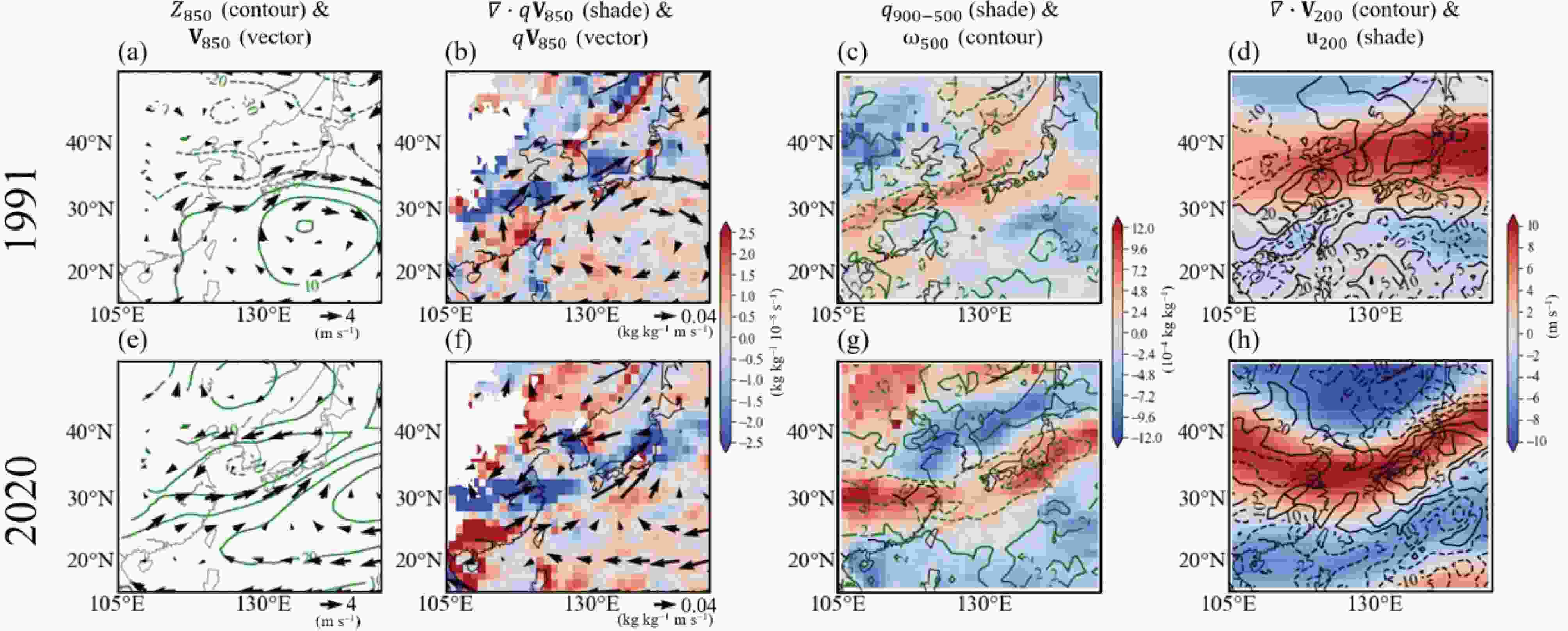

When we checked each of the individual precipitation diurnal cycles of AD-type years (Table 1), we found that 1991 represented a very similar patten to 2020 (Fig. 1b). Accordingly, we investigated and compared the synoptic/mesoscale features between these two years. Figure 7 depicts the anomalous synoptic patterns in the 1991 and 2020 cases for the same atmospheric variables as in Figs. 2 and 3. The synoptic features in 1991 and 2020 are very similar to the AD-type pattern. Although local cyclonic circulations are present near the west side of the Korean Peninsula, the strengthened WNPSH and associated southwesterly winds are found over the East China Sea in both 1991 and 2020 (Figs. 7a and 7e). Following these low-tropospheric circulations, anomalous moisture inflows (from the low latitudes to Korea) along the moisture convergence area are also identified (Figs. 7b and 7f). In addition, abundant moisture (positive specific humidity anomaly) and strong upward motion (negative vertical velocity anomaly) induced by the enhanced upper-tropospheric jet are present in the East China Sea and South Korea (Figs. 7c, 7d, 7g, and 7h). Figure7. Same as Figs. 2 and 3 except for two specific years, 1991 and 2020.

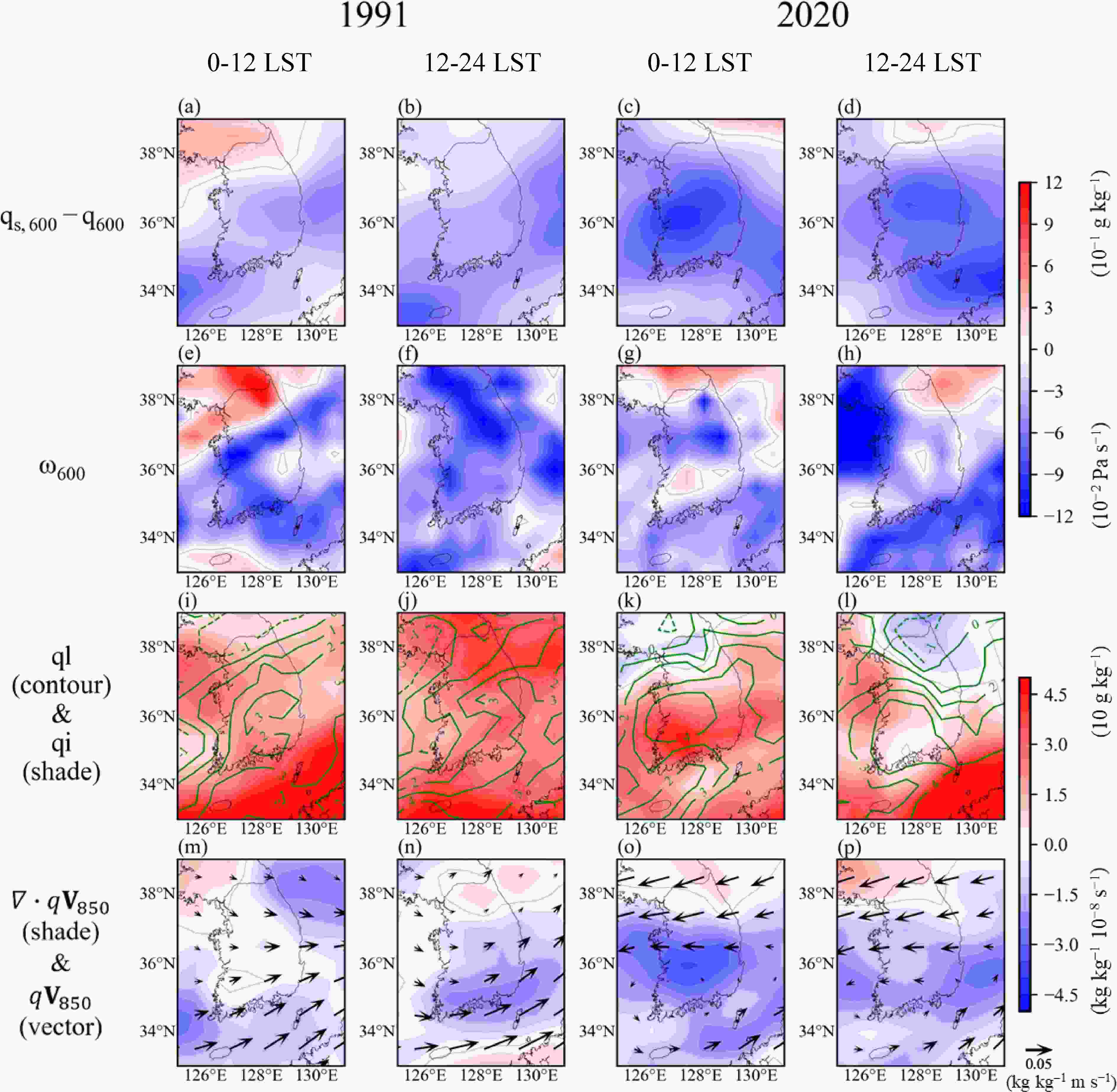

Figure7. Same as Figs. 2 and 3 except for two specific years, 1991 and 2020.Similarly, mesoscale features in 1991 and 2020 were investigated (Fig. 8). Although climatological mesoscale features contrast between the morning and the afternoon, their anomalies in 1991 and 2020 are generally consistent throughout the day, presenting typical AD-type patterns as discussed above. Negative moisture deficit anomalies indicate a relatively more humid condition than the climatology in both morning and afternoon (Figs. 8a–8d), which is consistent with the synoptic transport of abundant moisture. The anomalous vertical mass flux shows less coherent spatial patterns of negative anomalies than the moisture deficit. However, the vertical mass flux is generally enhanced, except for a few regions (Figs. 8e?8h). This indicates the occurrence of relatively active upward motions in 1991 and 2020, thereby favoring heavy rainfall all day long. Positive anomalies of the vertically integrated mass fraction of cloud liquid and ice water (Figs. 8i–8l) correspond well with the transport and convergence of abundant moisture (Figs. 8m–8p) and the attendant humid conditions. In other words, due to sufficient moisture supplies, cloud liquid and ice water remained even after heavy rainfall throughout the day in 1991 and 2020. Thus, these results show that despite some specific differences, the atmospheric conditions for the heavy rainfalls in 1991 and 2020 cases can be considered as the typical pattern of AD-type heavy rainfall in Korea.

Figure8. Same as Figs. 4 and 5 except for two specific years, 1991 and 2020.

Figure8. Same as Figs. 4 and 5 except for two specific years, 1991 and 2020.In Figs. 1b and 1c, the amount of rainfall in 2020 is much more than that in 1991. Although the general synoptic and mesoscale features of 2020 and 1991 are corresponed to the typical pattern of AD-type, some specific differences are found in Figs. 7 and 8. In particular, the moisture inflow (Figs. 7b, 7f and 8m?8p) and the mid-tropospheric saturation deficit (Figs. 8a?8d) in 2020 are generally greater than those in 1991. These differences may contribute to such rainfall amount difference between 2020 and 1991. However, because there are complex environmental processes and interactions between numerous factors that created the rainfall, further investigations may be needed to fully understand associated mechanisms incurring the rainfall amount difference between 2020 and 1991. This is beyond the scope of present study.

For both MO- and AD-types, heavy rainfall is mainly related to abundant cloud liquid water. This implies that the warm-type heavy rainfall mechanism is dominant in Korea, as previous studies have indicated. By contrast, for the AD-type heavy rainfall, abundant cloud ice water contents and active convection are also found, which are the main features of the cold-type heavy rainfall mechanism. Namely, the cold-type mechanism may partially contribute to the formation of heavy rainfall for the AD-type within the dominant warm-type mechanism. Song and Sohn (2020) suggested that for the summertime rainfall system in Korea during recent decades, the cold-type mechanism has become more frequent than the warm-type mechanism. This recent change may be related to the occurrence of the two distinct heavy rainfall peaks in the morning and afternoon for 1991 and 2020, which are the years categorized as having AD-type events (see Fig 1b). Thus, to fully understand the diurnal characteristics of heavy rainfall in Korea and their interannual/decadal variations, further investigation of the microphysical processes that are related to the formation of the two types of heavy rainfall are necessary.

The anomalous atmospheric circulations related to the heavy rainfall in the 2020 correspond well with those for the AD-type heavy rainfall. In addition, the diurnal cycle and associated synoptic and mesoscale features of the heavy rainfall in 1991 are very similar to those in the 2020 case, indicating that the events of 1991 are similar to those of 2020. These results present that severe heavy rainfall events in the 2020 were induced by the recurring atmospheric phenomenon related to the heavy rainfall in Korea.

Acknowledgements. This work was supported by the Korea Meteorological Administration Research and Development Program (Chang-Hoi HO and Minhee CHANG: KMI2020-00610), the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (Kyung-Ja HA: 2020R1A2C2006860, Chang-Kyun PARK: 2021R1C1C2004711), and Development and Assessment of AR6 Climate Change Scenarios (Jinwon KIM: KMA2018-00321).

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (