HTML

--> --> -->The diurnal variation is one of the most distinct features of local and global precipitation, the understanding of which is essential for a thorough understanding of regional weather and climate characteristics, energy budgets, and water balance (Sorooshian et al., 2002; Fu et al., 2006; Yu et al., 2007, 2014; Chen et al., 2012). When precipitation occurs frequently at a specific time of day, it typically implies that the atmospheric conditions and physical processes during that period favor convective activity (Sorooshian et al., 2002). Furthermore, analysis of the diurnal variations of precipitation can be used to validate and improve the accuracy of weather and climate model predictions (Yang and Slingo, 2001; Chen et al., 2012; Mao et al., 2012). Previous studies have shown that the underlying surface plays an important role in regulating diurnal variations of precipitation. This is thought to be attributed to the extremely uneven surface forcing caused by complex land-sea interactions and terrain distributions. For example, maximum precipitation is regularly observed in the afternoon and evening over land, but in the early morning over the ocean (Nesbitt andZipser, 2003; Fu et al., 2012; Yu et al., 2014). At land-sea boundaries, precipitation along the coast can spread over adjacent inland or offshore areas for several hundred kilometers due to gravity waves at specific times (Yang and Slingo, 2001; Zuidema, 2003; Mao et al., 2012). Moreover, increased elevation can sometimes cause unique diurnal variations that differ from the regular afternoon maxima over land (Fu et al., 2006). For example, precipitation over the Great Plains in the United States exhibits a nocturnal diurnal peak related to eastward propagation of convection systems from the Rockies, which account for a large proportion of summer precipitation (Wallace, 1975; Jiang et al., 2006).

The Himalayas and its surrounding areas are ideal for the analysis of orographically influenced diurnal variations in precipitation given their highly complex and steep terrain, which will inevitably lead to significant regional variations in diurnal precipitation. To date, the diurnal variations of precipitation in the TP and Himalayas have been widely studied using regional climate model, rain-gauge, and satellite data, all of which reveal remarkable diurnal variations. In summer, afternoon and evening maxima are dominant in the TP as a result of strong solar radiative heating (Liu et al., 2009). According to observations made using a C-band vertically-pointing frequency-modulated continuous-wave radar, stratiform and weak convective precipitation events contribute significantly to the evening and afternoon maxima, respectively (Ma et al., 2018). Diurnal cycles of precipitation and cloudiness exhibit clear eastward phase propagation, to the east and downstream of the TP, accompanied by a gradual strengthening (Yu et al., 2007; Xu and Zipser, 2011; Chen et al., 2012; Pan and Fu, 2015). Furthermore, the eastward propagation of deep convection is more profound than that of shallow precipitation (Pan and Fu, 2015). Precipitation in the foothills of the Himalayas is characterized by an early-morning maximum (Bhatt and Nakamura, 2005; Singh and Nakamura, 2010), which is associated with strong diurnal variations of circulation over the TP as determined by regional climate models (Chow and Chan, 2009). In addition, previous research has revealed complex local circulation systems in the TP and Himalayas, including mountain-valley and glacial winds (Bhatt and Nakamura 2005, 2006; Romatschke et al., 2010; Chen et al., 2012; Yu et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2019), which play an important role in diurnal precipitation patterns. For example, precipitation in mountainous areas tends to be more frequent in the afternoon, whereas precipitation in valleys tends to occur during the night into early morning (Barros et al., 2000; Barros and Lang, 2003; Fujinami and Yasunari, 2005; Zhang et al., 2018).

Owing to limited regional observational data, previous studies have generally focused on the diurnal variations of accumulated rainfall and rain frequency (RF) in the TP and Himalayas using ground observation stations or short-period Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission (TRMM) precipitation radar (PR) data to generate a domain average. Other parameters, such as rain rate (RR), storm top altitude (STA), brightness temperature (TB10.8) of precipitating clouds, and three-dimensional information of precipitation, have rarely been studied. Furthermore, the effects of topography on diurnal variations and the detailed propagation of precipitation over the steep slopes of the Himalayas are not sufficiently understood.

Based on the research of Fu et al. (2018), this study further analyzes diurnal variations of precipitation and circulation over the steep slopes of the Himalayas and surrounding areas during the rainy season (May–August) using long-term (1998–2012) collocated TRMM PR, visible infrared scanner (VIRS), and topographic data, as well as the following reanalysis products; National Centers for Environmental Prediction (NCEP) data, Climate Forecast System Reanalysis (CFSR) data and the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF)-Interim data.

The aims of this study are to: 1) reveal the relationship between diurnal variations of precipitation and terrain, specifically, the regional diurnal variations of precipitation observed in plain, foothill, steep slope, and mountain regions, 2) study the propagation of precipitation over the steep slopes of the Himalayas, and 3) reveal the diurnal variations in atmospheric circulation and better understand the possible mechanisms for diurnal variations in precipitation over the steep slopes of the Himalayas. This research contributes to our understanding of the climatic characteristics, land-atmosphere interactions, and precipitation formation mechanisms in areas of complex terrain. In addition, the findings can be used to validate and improve the accuracy of weather models applied to complex terrain.

The remainder of this manuscript is organized as follows. Sections 2.1 and 2.2 provide a brief description of the data and methods, respectively. Section 3.1 describes the daily variations of RF, RR, STA, and TB10.8, section 3.2 details the vertical structures of diurnal variation of precipitation, section 3.3 describes the influence of topography on diurnal variations of precipitation, and section 3.4 describes the diurnal variations of circulation and discusses possible mechanisms which explain the observed diurnal variations of precipitation. Finally, section 4 presents the conclusions and summary.

2.1. Data

TRMM is a sun-synchronous satellite launched in 1997 with the intent of providing systematic and quantitative measurement of tropical to mid-latitude rainfall and energy exchange. It was the first satellite with onboard spaceborne PR and the first to integrate PR, VIRS, TRMM Microwave Imager (TMI), Lightning Imaging Sensor (LIS), and Clouds and Earth's Radiant Energy System (CERES) for the purpose of detecting clouds, precipitation, and lightning, thereby representing substantial progress in precipitation research. A number of studies have indicated that the distribution features of precipitation derived from TRMM PR measurements is in agreement with that of ground-based observations at climatological scale over the TP and Himalayas (Barros et al., 2000; Bookhagen and Burbank 2006, 2010; Liu et al., 2010). Additionally, rain rates detected by PR at low-altitude stations demonstrate better skill compared with those at high elevation stations (Barros et al., 2000), which may be related to the spatial density of rain gauges (Liu et al., 2010). The precipitation data provided by TRMM have high spatial and temporal resolution, which compensates for the shortcomings of scattered, scarce, and insufficient observations from ground stations, ultimately providing for a new opportunity to study precipitation over the steep slopes of the Himalayas (Fu et al., 2018).Previous studies have shown that the Asian monsoon rainy season usually begins in mid-May (Wang and LinHo, 2002); therefore, we define the rainy season as the period from May to August (Fu et al., 2018). This study employed collocated Version 7 TRMM PR (2A25) and VIRS (1B01) data, scan by scan, for 15 consecutive years (1997–2012) of rainy seasons. The rain profiles of 2A25 are three-dimensional precipitation data from sea level to 20-km height retrieved from the detected echo signals of PR. PR data have 49 pixels in each scan with a horizontal resolution of approximately 4.3 km (5 km) pre-(post) boost and a vertical resolution of 250 m near the radar nadir. 1B01 data represent the reflectivity and brightness temperature after VIRS calibration. VIRS data have 261 pixels in each scan with a horizontal resolution of 2.2 km. Considering the different resolutions between PR and VIRS, the weighted average of VIRS pixels in a PR pixel was obtained to derive the corresponding VIRS value of each PR pixel and reduce the resolution of VIRS to the same as that of PR (Fu et al., 2011). The results indicated that the TB of the 10.8-μm channel exhibited no distortion when the average value changed by less than 0.7%, and the mean square error was less than 2.5% after the collocating process; therefore, the collocated data was deemed valid. PR and VIRS collocated data have also been widely used in previous research (Liu and Fu, 2010; Fu and Qin, 2014; Pan and Fu, 2015; Fu et al., 2016, 2018).

The topographic data were derived from the ETOPO2v2 Global Database issued by the National Geophysical Data Center of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (Amante and Eakins, 2009; available at

Climatological surface (0.995 sigma level) winds were derived from the NCEP CFSR from 1998–2010 and the NCEP Climate Forecast System dataset, version 2 (CFSV2) from 2011–2012 with 6-h temporal resolution and 0.5° spatial resolution (Qie et al., 2014; Fu et al., 2018). Vertical circulation and atmospheric parameters were extracted from ECMWF-Interim reanalysis data with 6-h temporal resolution and 0.25° spatial resolution. The datasets provide 36 pressure-level layers, with a resolution of 25-hPa intervals below 750 hPa, and 50-hPa intervals between 750–250 hPa. Circulation in the radial direction comprises the u and v wind components.

2

2.2. Methods

TRMM PR operates at a frequency of 13.8 GHz; therefore, it cannot effectively detect reflectivity down to 17 dBZ, which is equivalent to a rain intensity of approximately 0.4 mm h–1. Consequently, only the rain samples with a near-surface rain intensity equal to or greater than 0.4 mm h–1 were considered (Schumacher and Houze, 2003; Chen et al., 2016; Fu et al., 2018). RF was defined as the rain samples in each bin divided by the corresponding total pixel numbers detected by PR to remove the zonal inhomogeneity sampling bias. STA is the maximum height of 20-dBZ PR reflectivity detected by PR, which is an indicator of how high the updraft can lift precipitation-sized ice particles (Liu and Zipser 2005; Houze et al., 2007; Liu et al., 2007; Chen et al. 2016; Fu et al. 2012, 2018).The value of TB10.8 can reflect the height and phase of the cloud top. Generally, clouds with TB10.8 values below 233 K indicate an ice phase, whereas clouds with TB10.8 values greater than 273 K indicate a water phase, and clouds with TB10.8 values between 233 K and 273 K indicate a mixed phase (Braga and Vila, 2014; Fu and Qin, 2014; Fu et al., 2018).

The contoured frequency by altitude diagram (CFAD, Yuter and Houze, 1995) displays the frequency of precipitation echo intensity at each height. It is an effective method of representing the vertical structure of precipitation. Here, the CFAD was normalized (NCFAD) by dividing by the maximum absolute frequency of samples within the region for the entire day, which enables comparisons between different periods. The NCFAD values used in this study were truncated by 20 dBZ to reduce noise according to the sensitivity of the TRMM PR (Fu et al., 2018).

In order to highlight the significance of the diurnal variation, the diurnal variation curves were normalized by the following formula:

where

where P and

According to distributions of topography, atmospheric circulation, and precipitation (Chen et al., 2017; Fu et al., 2018), four belt-shape sectors from the northern plains of India via the foothills to the steep slopes of the Himalayas and the Himalayan–Tibetan Plateau tableland were selected, as shown in Fig. 1a. The four regions represent the flat Gangetic Plains (FGP), the foothills of the Himalayas (FHH), the steep slopes of the southern Himalayas (SSSH), and the Himalayan–Tibetan Plateau tableland (HTPT), respectively. Rain samples based on the 0.25° × 0.25° grid were abundant (Fig.1), averaging more than 100 except for some grids during some time periods; rain samples of less than 50 were neglected. Therefore, the results have statistical significance based upon the 0.25° × 0.25° grid.

Figure1. Distributions of rain samples in six time periods in rainy seasons from 1998–2012. (a) Early morning, (b) morning, (c) noon, (d) afternoon, (e) evening, and (f) midnight. I, II, III and IV represent FGP, FHH, SSSH, and HTPT, respectively, and black dashed lines represent the boundaries of each region.

Figure1. Distributions of rain samples in six time periods in rainy seasons from 1998–2012. (a) Early morning, (b) morning, (c) noon, (d) afternoon, (e) evening, and (f) midnight. I, II, III and IV represent FGP, FHH, SSSH, and HTPT, respectively, and black dashed lines represent the boundaries of each region.3.1. Daily variation of RF, RR, STA, and TB10.8

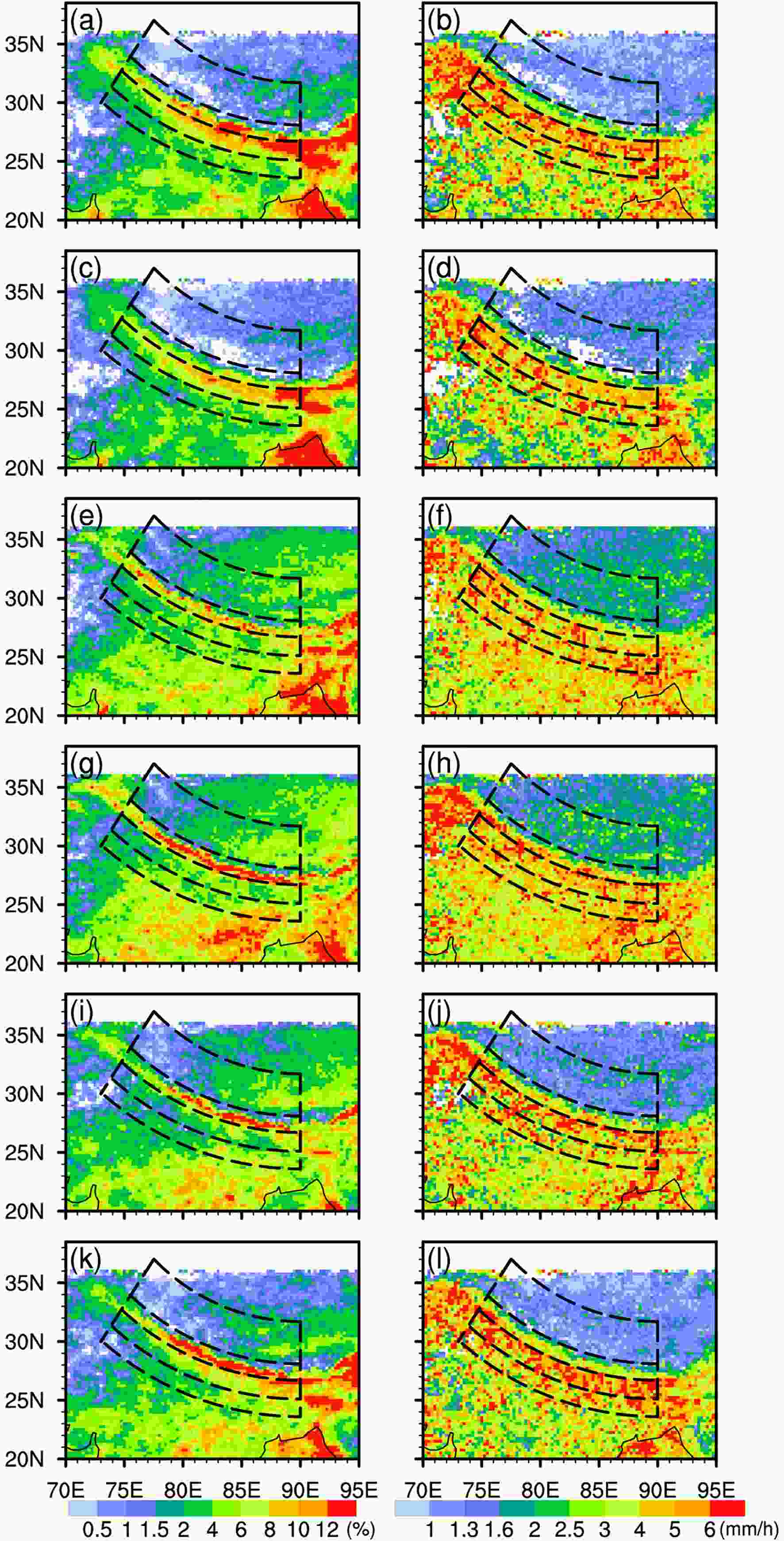

The distributions of diurnal variations of RF and RR, over the six periods, in a 0.25o × 0.25o grid, are displayed in Fig. 2. Large diurnal variations are observed throughout the study region. At FGP, RF increases starting at noon, peaking in the afternoon (~4%), and then begins to decrease until morning (~2%). At FFH, RF tends to increase starting at midnight and reaches a maximum value (8–10%) in the early morning. Precipitation during this period is predominantly downslope winds precipitation and easterly circumfluent precipitation (Zhang et al., 2018). RF then decreases until the evening (~6%). Rain is most frequent at SSSH and exhibits a large gradient (Fu et al., 2018). RF at higher elevations in the north of SSSH mainly peaks in the afternoon (~2%), and RF at lower elevations in the south has a peak close to midnight (> 12%). RF reaches a minimum in the morning, especially in the highest of the Himalayan mountains, where there is almost no rain. At HTPT, RF increases significantly from noon as a result of forcing attributed to land surface heating, especially in the central TP. RF mainly peaks in the afternoon over the western and central HTPT, and in the evening over the southeast HTPT, with a few hours delay relative to the western and central HTPT, which may be related to precipitation forming when the convective clouds move eastward. In most areas, RF decreases rapidly from the evening and reaches a minimum in the morning, which agrees with model simulation results that generate minimal precipitation in the TP because air flow is deflected around the mountains beginning around midnight and lasting into the morning (Wu et al., 2012). The diurnal variations of RR are relatively weaker than those of RF. At FGP, RR mainly peaks from noon to the afternoon (4~5 mm h–1) and reaches a minimum (~3 mm h–1) in the morning. At FHH, RR begins to strengthen from the afternoon, then reaches a peak from midnight to early morning and a minimum at noon. Over SSSH, RR peaks at noon at higher elevations and at midnight at lower elevations, with the minimum occurring in the morning. At HTPT, RR begins to increase from noon and reaches a maximum in the afternoon, then decreases until early morning. Figure2. Distributions of RF (left) and RR (right) in the six time periods in rainy seasons from 1998–2012. (a, b) early morning, (c, d) morning, (e, f) noon, (g, h) afternoon, (i, j) evening, and (k, l) midnight, and black dashed lines represent the boundaries of each region.

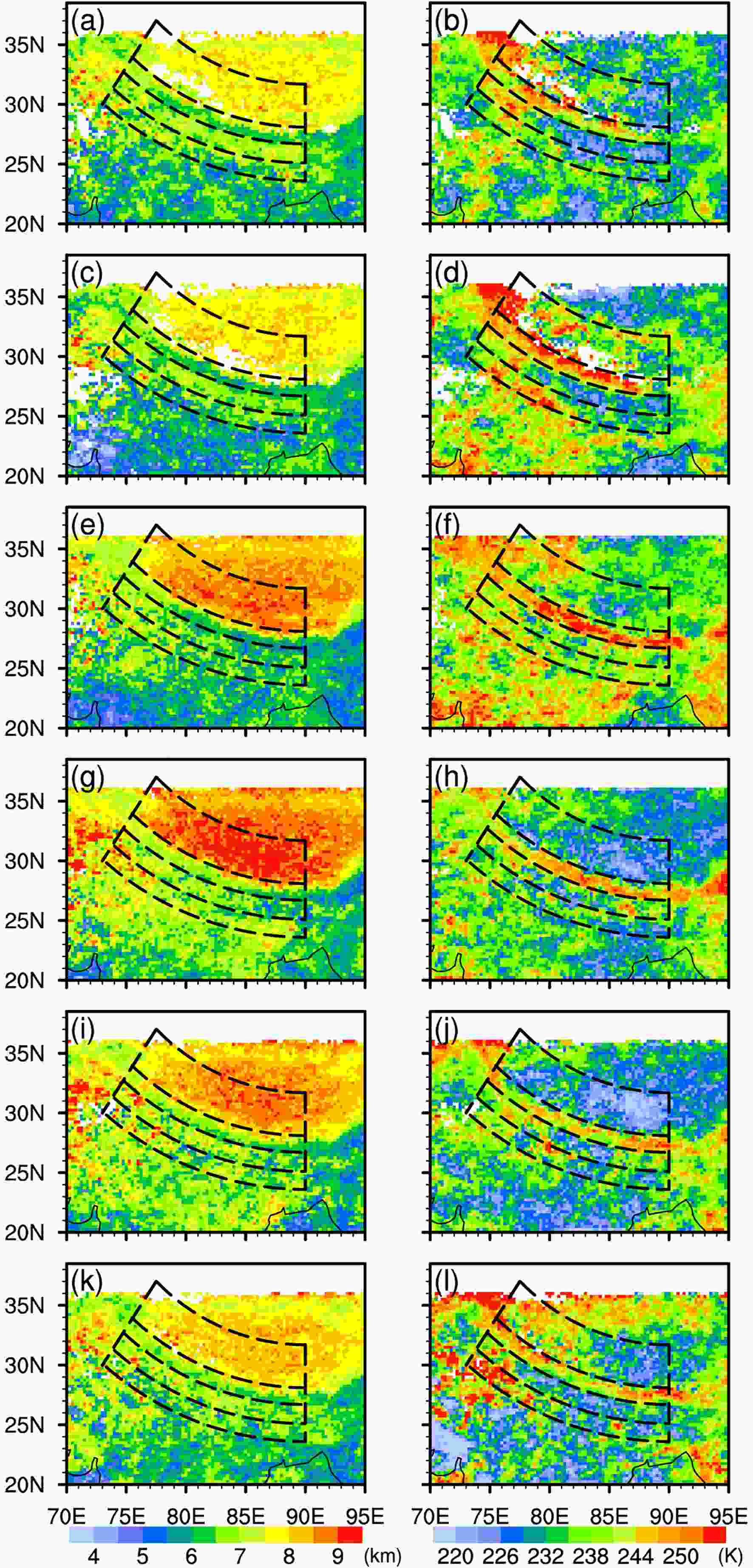

Figure2. Distributions of RF (left) and RR (right) in the six time periods in rainy seasons from 1998–2012. (a, b) early morning, (c, d) morning, (e, f) noon, (g, h) afternoon, (i, j) evening, and (k, l) midnight, and black dashed lines represent the boundaries of each region.The corresponding distributions of diurnal variations of STA and TB10.8 in the six periods are displayed in Fig. 3. Because of intense solar heating during the day, the STAs over FGP, SSSH, and HTPT develop around noon, and reach a peak in the afternoon in most areas, with maximum values of approximately 7.5 km, 7 km, and greater than 9 km, respectively. At FHH, STA begins to develop around noon, and reaches a maximum (~7.5 km) in the morning, then gradually decreases, reaching a minimum (~6 km) at noon. Generally, TB10.8 represents the cloud top temperatures when clouds exist; therefore, it is interesting to determine if the diurnal variations for precipitating cloud tops are the same as those of STA. Peaks of TB10.8 at HTPT and FGP are mainly concentrated in the evening, and the peaks at FHH typically occur from early morning to morning. According to the TB10.8 values (< 233 K), the precipitation-topped clouds are predominantly composed of ice-phase particles during these periods. Peaks of TB10.8 (~240 K) over SSSH are concentrated during the midnight, and the precipitation cloud top is mainly composed of mixed particles. The peaks of TB10.8 occur a few hours after those of STA, indicating that the cloud top height is maintained and continues to develop when STA reaches its peak. In addition, the lower value of TB10.8 during the night may also be related to the enhanced surface radiational cooling. This observed relationship between STA and clouds is an interesting topic for future investigation. The peak distributions of parameters are consistent with the results proposed by Yu et al. (2013). The precipitation process is asymmetric, and the precipitation intensity can peak a very short time after the onset of precipitation; however, the peak toward the end of precipitation event lasts a long time. This leads to differences in the peak times among the different parameters.

Figure3. Distributions of STA (left) and TB10.8 (right) in the six time periods in rainy seasons from 1998–2012. (a, b) early morning, (c, d) morning, (e, f) noon, (g, h) afternoon, (i, j) evening, and (k, l) midnight, and black dashed lines represent the boundaries of each region.

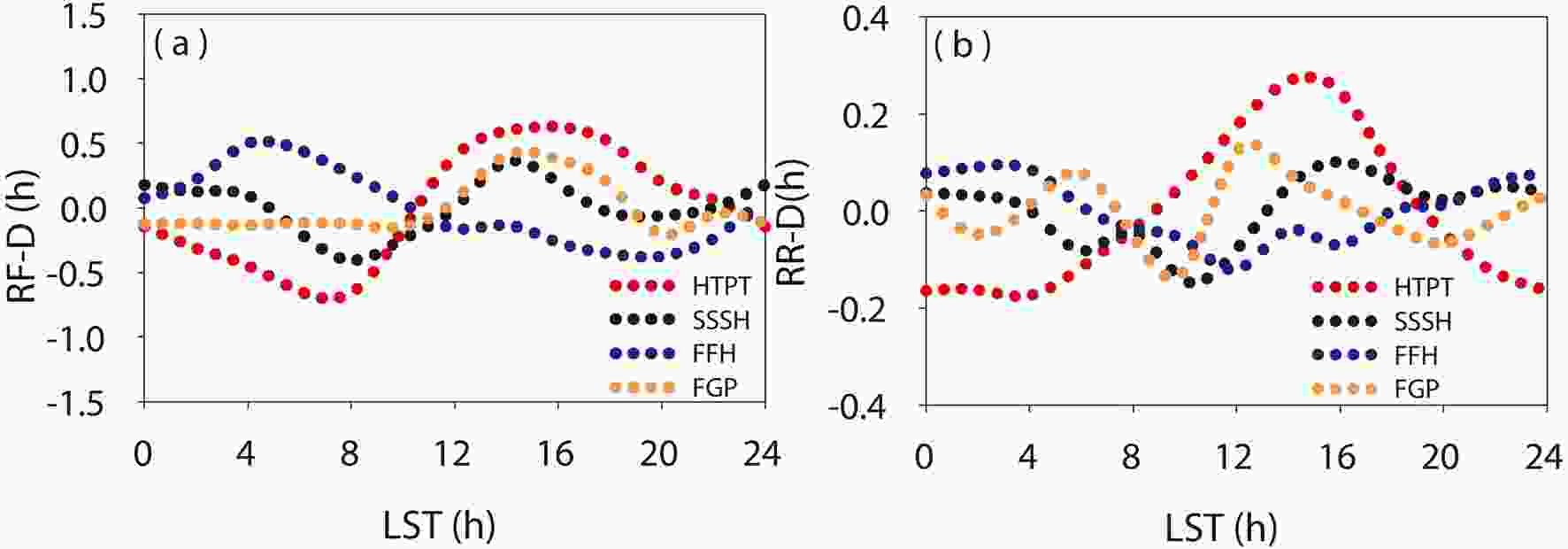

Figure3. Distributions of STA (left) and TB10.8 (right) in the six time periods in rainy seasons from 1998–2012. (a, b) early morning, (c, d) morning, (e, f) noon, (g, h) afternoon, (i, j) evening, and (k, l) midnight, and black dashed lines represent the boundaries of each region.Figure 4 shows the normalized diurnal variation curves of RF and RR in the four study areas. The RF daily variation curve at FGP has a unimodal structure and is gentler than that in other regions. Rain predominantly occurs between 1300 LST and 1800 LST, with a maximum at 1600 LST, and is less frequent from 0000–1000 LST, with minimal variation during the latter period. At FHH, rain mainly occurs from 0300–0600 LST, with a maximum at 0400 LST, then begins to decrease until 2000 LST. This suggests that low-altitude warm and wet rapids are important causes of nighttime convective formation and preservation (Houze et al., 2007). The diurnal variation curve of RF at SSSH has a bimodal structure with the first peak at 1500 LST and a second less pronounced peak at 0000 LST. The minimum value appears at 0800 LST. The diurnal variation at HTPT is the most significant of the four regions. The RF daily variation curve has a unimodal structure with a peak at 1600 LST and a minimum at 0800 LST. RR shows a similar diurnal variation pattern to RF, but the peaks are roughly 1–2 h earlier in most areas, except over SSSH, where RR exhibits a bimodal pattern with peaks at 1600 LST and 0000 LST. Moreover, RF has a heavier tail than RR during the evening over HTPT and FGP, which is indicative of numerous light showers from weak and less-organized convection (Liu et al., 2009). A second peak occurs around 0600 LST over FGP, which may be related to nighttime precipitation over the southern domain of FHH.

Figure4. Normalized diurnal variation curves of (a) RF and (b) RR over the study region in rainy seasons from 1998–2012.

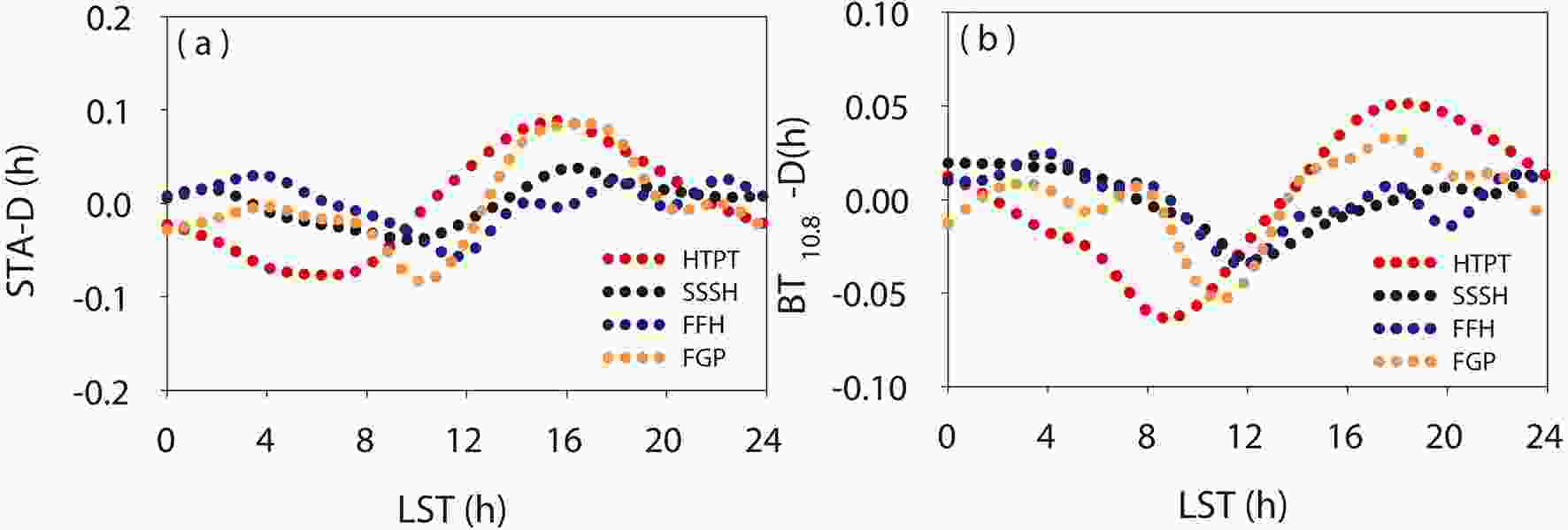

Figure4. Normalized diurnal variation curves of (a) RF and (b) RR over the study region in rainy seasons from 1998–2012.The corresponding normalized daily variation curves of STA and TB10.8 are depicted in Fig. 5. At FGP, the daily variation curves exhibit a bimodal pattern, with the main and secondary peaks at 1600 LST and 0400 LST, respectively. At FHH, STA reaches a maximum and minimum at 0400 LST and 1200 LST, respectively. At SSSH, the daily change curve is similar to that of RR, with two peaks at 1600 LST and 0200 LST, respectively, and the minimum at 1000 LST. The daily variation curve of STA at HTPT is very similar to that of RF, exhibiting a unimodal structure with the peak at 1600 LST and the minimum at 0700 LST, which is consistent with the cloud characteristics at Nagqu calculated by Cloud Radar by Liu et al. (2015). The daily variation curve of TB10.8 shows that the precipitation clouds with a higher cloud top height at FGP and HTPT are concentrated within the period, 1600–2200 LST, and the TB10.8 value peaks at 1800 LST, lagging behind other parameter peaks, before reaching a minimum at 1200 LST. For FHH and SSSH, higher precipitation cloud top heights typically occur from midnight to early morning, with the peaks at 0000 LST and 0400 LST respectively, before decreasing until 1200 LST.

Figure5. Normalized diurnal variation curves of (a) STA and (b) TB10.8 over the study region in rainy seasons from 1998–2012.

Figure5. Normalized diurnal variation curves of (a) STA and (b) TB10.8 over the study region in rainy seasons from 1998–2012.2

3.2. Diurnal variation characteristics of the vertical precipitation structure

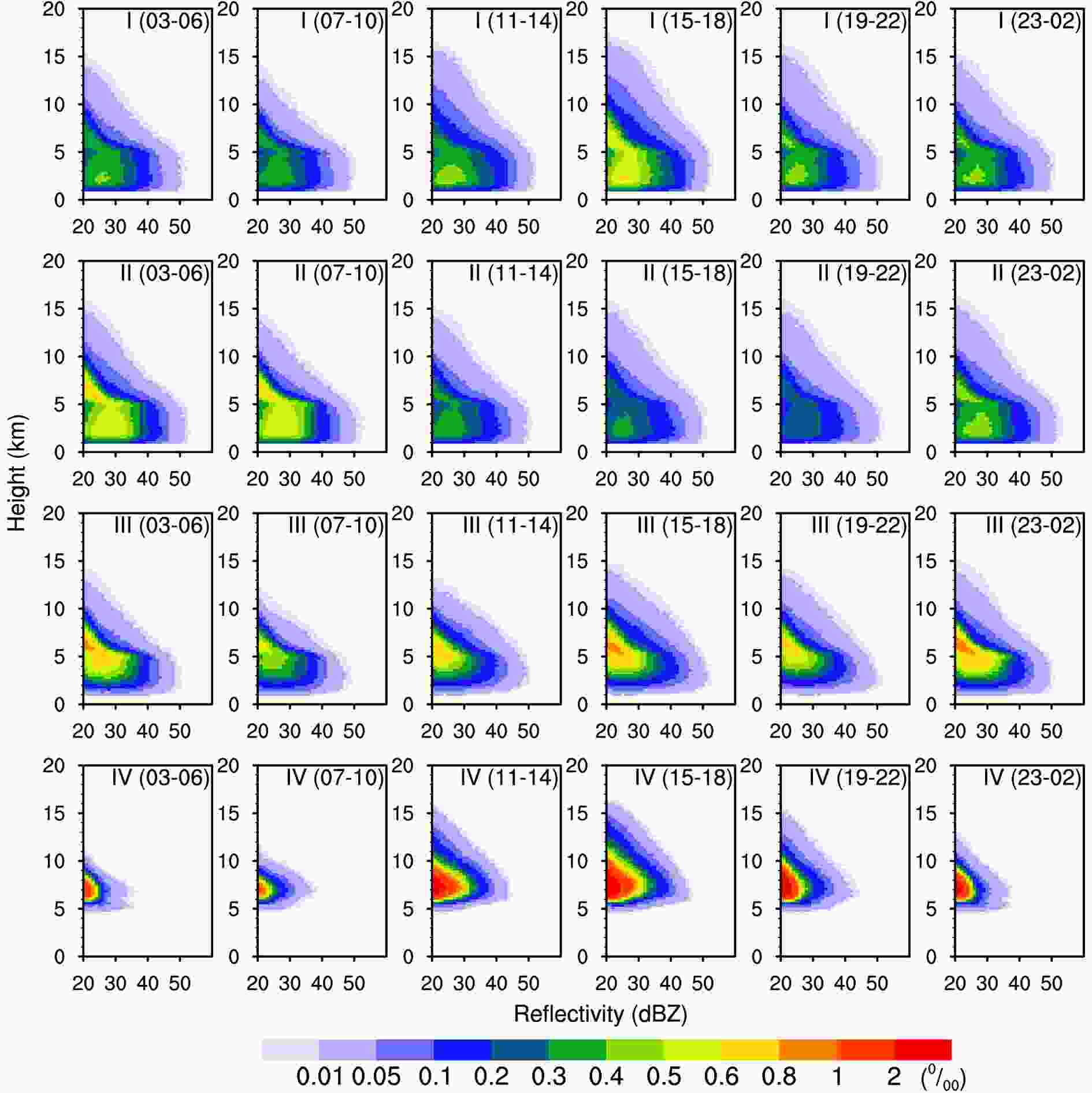

Figure 6 shows the distribution of NCFAD in the six periods for each region. At FGP, the vertical structure starts to develop at noon and is most vigorous in the afternoon, with the largest value. During this period, the strongest echo exceeds 50 dBZ, and the 20-dBZ and 40-dBZ echo heights can reach up to 17 km and 12 km, respectively, indicating deep strong convection (40-dBZ echo reaching heights > 10 km, Houze et al, 2007; Xu, 2013). Then, the precipitation begins to weaken to a minimum in the morning with a 20- (40-) dBZ echo height at 14 (8) km, and echo greater than 40 dBZ is less frequent. At FHH, the vertical structure of precipitation begins to develop at midnight, with the most vigorous development and largest value occurring in the early morning. The echo top height of 20 (40) dBZ reaches 16 (8) km before the precipitation begins to weaken, with the weakest development at noon and an echo top height of 20 (40) dBZ of approximately 15 (7) km. At SSSH, vertical structure development is most vigorous in the afternoon and at midnight, with a maximum echo greater than 50 dBZ, and the echo top height of 20 (40) dBZ can reach 14 (8) km. The convection is most shallow in the morning with a maximum echo of approximately 49 dBZ, when the echo top height of 20 (40) dBZ is only 12 (6) km. Over FGP, FHH, and SSSH, clear bright band features are observed (frequency has obvious right shift) near the 0°C layer in an echo intensity range of less than 40 dBZ; these bright band features are more pronounced from midnight to early morning, indicating a greater tendency for stratiform precipitation to occur during this period with relatively stable stratification (Houze, 1997). The diurnal variation of convective activity is most significant over HTPT. The convective activity starts to strengthen in the morning and becomes strongest in the afternoon. The echo height of 20 dBZ can reach 16 km and the maximum echo intensity is approximately 45 dBZ. The vertical structure shows obvious convective precipitation characteristics, indicating that precipitation is accompanied by strong upward movement and conditionally unstable stratification (Houze, 1997). The convective activity then begins to weaken until the early morning with a 20-dBZ echo top height of approximately 11 km and a maximum echo intensity of approximately 35 dBZ. Figure6. Distributions of NCFAD in the four study regions in the six time periods. Regions I, II, III, and IV represent FGP, FHH, SSSH, and HTPT, respectively.

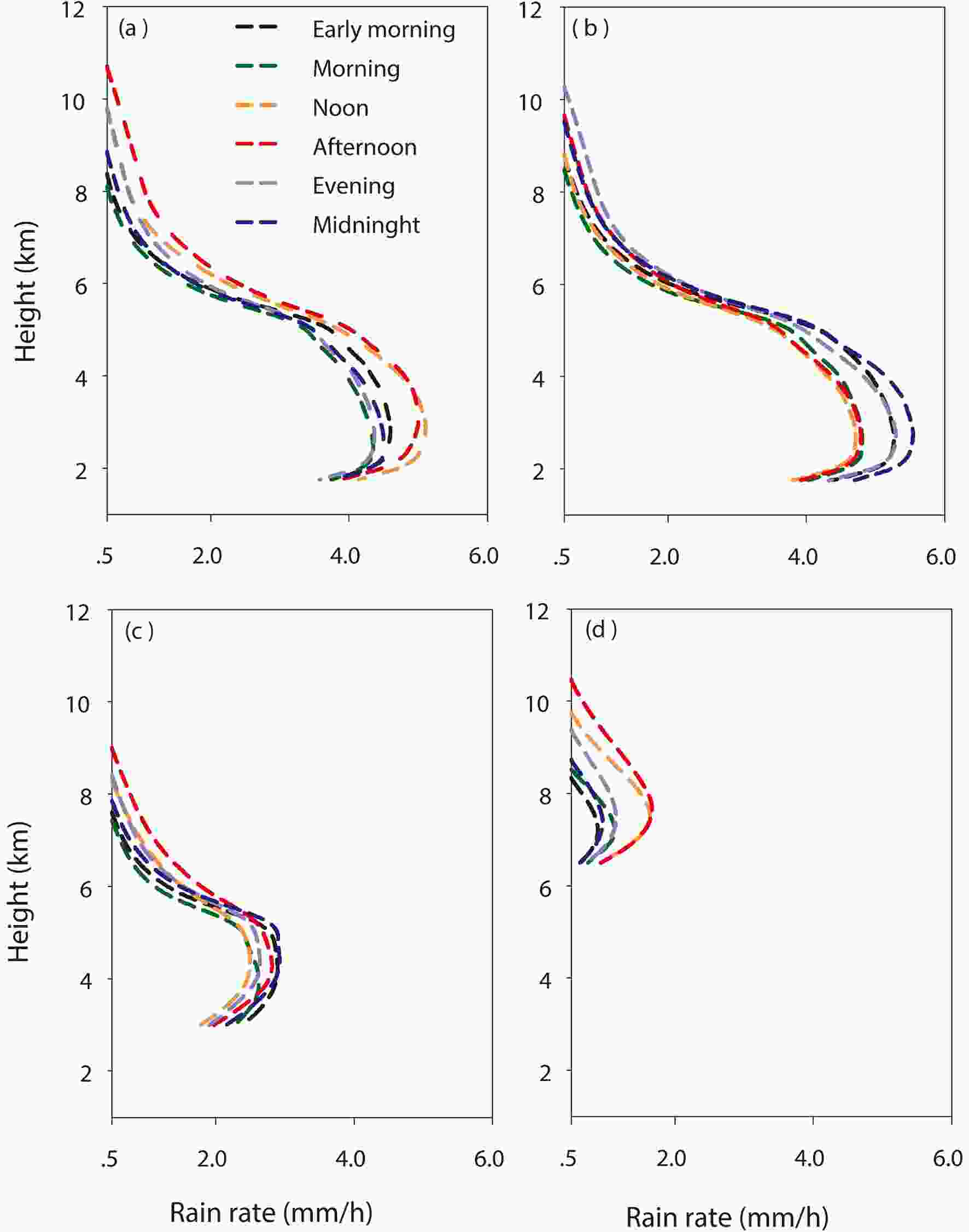

Figure6. Distributions of NCFAD in the four study regions in the six time periods. Regions I, II, III, and IV represent FGP, FHH, SSSH, and HTPT, respectively.The precipitation profile can reflect upon the thermodynamic structure and microphysical characteristics of precipitating clouds (Fu et al., 2008). Figure 7 shows the average precipitation profiles in the six periods for each region, which exhibit obvious daily variation differences and clearly reveal the microphysical characteristics reflected in the precipitating clouds. According to the research results of Fu et al. (2018), the FGP and FHH precipitation profiles are divided into four vertical layers based on the echo gradient of precipitation profile: ground level to 2.5 km is an evaporation layer for rain droplets; from the top of the evaporation layer to the freezing layer (~5 km) is a layer of coalescence for different particle sizes with different phases; from the top of the coalescence layer to 7 km is a mixed layer of different particle phases; and from the mixture layer upward is a layer of particle crystallization. Over FGP, the daily variation of STA can vary from 8–11 km. The average STA is highest (~11 km) in the afternoon, when the crystallization layer is the thickest, which indicates that there are abundant ice-phase particles in the precipitating cloud. Furthermore, the precipitation intensity changes most rapidly within the boundaries of the coalescence layer during this time, that is, the collision-based growth process is most intense, corresponding to the largest RR (~4.7 mm h–1). In the morning, the average STA is the lowest (~ 8 km) and the rainfall intensity changes the slowest within the coalescence layer, with the smallest RR (~ 4.1 mm h–1). Compared with FGP, the precipitation intensity over FHH in the coalescence layer changes more substantially with more intense raindrop accretion, and is most intense and least intense at midnight and noon, respectively, corresponding to the maximum and minimum RR. The daily variation of STA is relatively small, with the highest in the evening (~10.5 km) and the lowest in the morning (8.5 km). The vertical profile over SSSH based on rain rate gradient can also be divided into four layers. From near the ground to 4 km is an evaporation layer of rain droplets. From the top of the evaporation layer to the frozen layer, the precipitation profile remains approximately unchanged with no raindrop collision or growth. From 5 km to 7 km, the rain rate gradient in the mixed layer exhibits a large diurnal variation difference, and the ice and water mixture is the most intense at midnight, corresponding to the larger RR. At noon, the mixture is the weakest, corresponding to the smallest RR. Above the mixed layer is a layer of particle crystallization, and this layer is thickest in the afternoon. Over HTPT, the rain profile at each time is divided into two layers with heights of 7.5 km, and convection is shallower because of the much thinner air mass over the plateau (Fu et al., 2018). The daily variation in the vertical profile is most obvious here, with the highest STA and largest RR in the afternoon and the lowest STA and smallest RR in the morning.

Figure7. Distribution of precipitation profiles in the four study areas in the six periods, (a), (b), (c), and (d) represent FGP, FHH, SSSH, and HTPT, respectively.

Figure7. Distribution of precipitation profiles in the four study areas in the six periods, (a), (b), (c), and (d) represent FGP, FHH, SSSH, and HTPT, respectively.2

3.3. Influence of topography on diurnal variations of precipitation

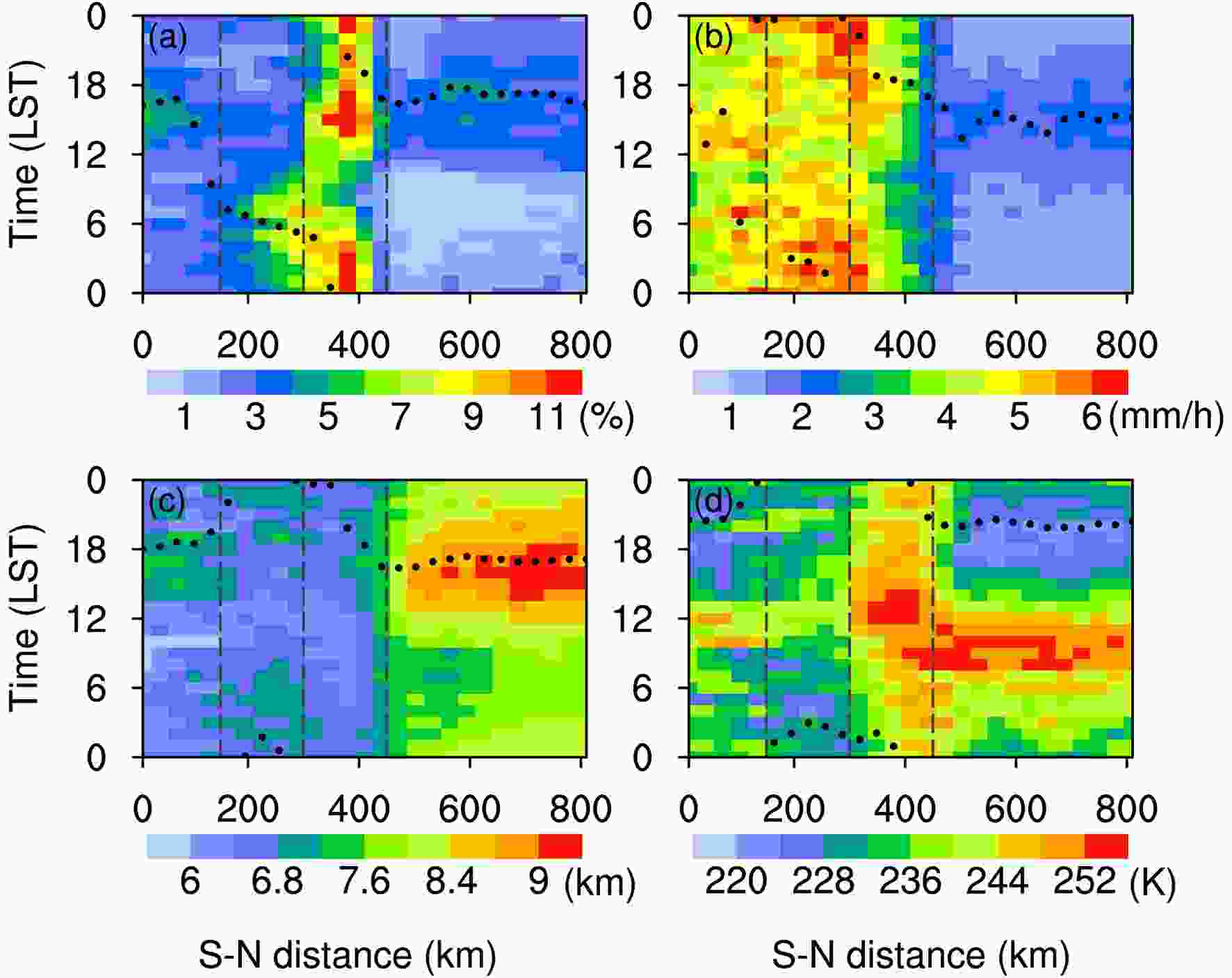

Here, we describe how the diurnal variations of precipitation vary with topography. The evolution of precipitation parameters (RF, RR, STA, and TB10.8) with time along the radial direction, from south to north, in the study region, is shown in Fig. 8. Over HTPT, the RF increases sharply from less than 1% at 1100 LST to a peak of 5% around 1600 LST, then weakens steadily to 1% between midnight and morning. All diurnal harmonic phases are centered at approximately 1600 LST. RR increases dramatically from less than 1 mm/h at 1100 LST to a peak value (> 2 mm h–1) at 1500 LST, then gradually decreases to a minimum (< 1 mm h–1) in the morning. The phase is centered around 1500 LST, which is approximately one hour earlier than the RF phase in Fig. 8a, indicating that the RF peaks are approximately 1–2 h behind those of the rainfall amount (Liu et al., 2009). STA increases from less than 7.5 km at 1100 LST to an average maximum of 9 km at approximately 1600 LST, then decreases until the morning (~7.5 km). TB10.8 varies from 220–252 K, with the lowest values (less than 230 K) at 1600–2200 LST, indicating that the precipitation cloud is predominantly composed of ice particles at this time. TB10.8 values are highest at 0800–1200 LST, with values of 240–260 K, indicating that the precipitating cloud is predominantly mixed particles. The phase appears close to 2100 LST, which represents a delay compared to other precipitation parameters. Figure8. Evolution of (a) RF, (b) RR, (c) STA, and (d) TB10.8 with time during rainy seasons from 1998–2012 averaged along the radial direction from south (S) to north (N) in the sector areas shown in Fig. 1a. Black dots represent the diurnal harmonic phase, gray solid lines represent the corresponding average altitude, and black dashed lines represent the boundaries of each region. (Note: the average has a resolution of approximately 0.1° in the X-axis and 0.25 km in the Y-axis).

Figure8. Evolution of (a) RF, (b) RR, (c) STA, and (d) TB10.8 with time during rainy seasons from 1998–2012 averaged along the radial direction from south (S) to north (N) in the sector areas shown in Fig. 1a. Black dots represent the diurnal harmonic phase, gray solid lines represent the corresponding average altitude, and black dashed lines represent the boundaries of each region. (Note: the average has a resolution of approximately 0.1° in the X-axis and 0.25 km in the Y-axis).As shown in Fig. 8a, over SSSH, RF varies from 5% to 12%, and the maximum value appears at a height of 2 km in the hillside. Precipitation mainly occurs from the afternoon until early morning. The phase is centered around 1500 LST at higher altitude and 0000 LST at lower altitude, respectively. Precipitation seldom occurs from early morning to morning, with RF values of less than 7%. The diurnal harmonic phase distributions of RR (Fig. 8b) and STA (Fig. 8c) are similar to RF, but the phase of RR is roughly 1–2 h earlier. TB10.8 varies from 236–252 K (Fig. 8d), which is higher than the surrounding area, indicating that the average precipitation cloud top height in this area is lower than that in the surrounding area and mostly composed of mixed precipitation clouds (Fu et al., 2018). The diurnal harmonic phase distribution of TB10.8 is similar to RF, but the phase lags behind a few hours.

From early morning to morning, the center of the RF peak moves southward and widens to FHH, reaching a maximum value (~6%), before weakening from 1200 LST to a minimum value (~2%) close to 2100 LST. The RF phase moves southward from the lower elevations over SSSH to FHH at a speed of approximately 25 km h–1 from 0000 LST to 0800 LST. RR is greater from midnight to morning with a maximum of more than 6 mm h–1; the phase value varies from 0000 to 0400 LST. STA varies in the range of 6–7 km and is higher from midnight through early morning with the phase appearing close to 0100 LST. TB10.8 varies from 228~240 K with a minimum in the early morning; the cloud top is predominantly ice particles at this time. TB10.8 reaches a maximum at noon, when the cloud top is mainly composed of mixed particles.

The daily variation characteristics of FGP are similar to those of HTPT. RF varies in the range of 2–4% with the phase appearing close to 1600 LST. RR varies in the range of 3.5–5.5 mm h-1 and is larger from 1200–1700 LST. Near the boundary of FHH, RF and RR are also stronger from midnight to early morning, which may be related to the propagating convective system from FHH. STA varies in the range of 6~7.5 km with the phase appearing close to 1800 LST. STA is higher from afternoon to evening and lower in the morning. TB10.8 varies in the range of 228–244 K, with the phase appearing close to 2100 LST.

The corresponding standard amplitudes and percentage variance of the diurnal harmonic wave are shown in Fig. 9. The RF normalized amplitude is the largest, with the most significant diurnal variation, whereas the TB10.8 normalized amplitude is the smallest, exhibiting relatively weak diurnal variation. The standardized amplitude of all parameters is largest in HTPT, having diurnal percentage variances of more than 80%, which indicates that the diurnal variation is quite dramatic over HTPT. The smallest standardized amplitude is located at the boundary between each area, which is consistent with the fact that the daily variability is weaker around the TP periphery (Liu et al, 2009), especially for the junction between FGP and FHH. This suggests that half-day variation characteristics may exist in this region.

Figure9. Standardized amplitude (red dotted line) and percentage of variance explained by the diurnal harmonic (blue dotted line) for (a) RF, (b) RR, (c) STA, and (d) TB10.8. Gray solid lines represent the corresponding average altitude and long dashed black lines represent the boundary of each region.

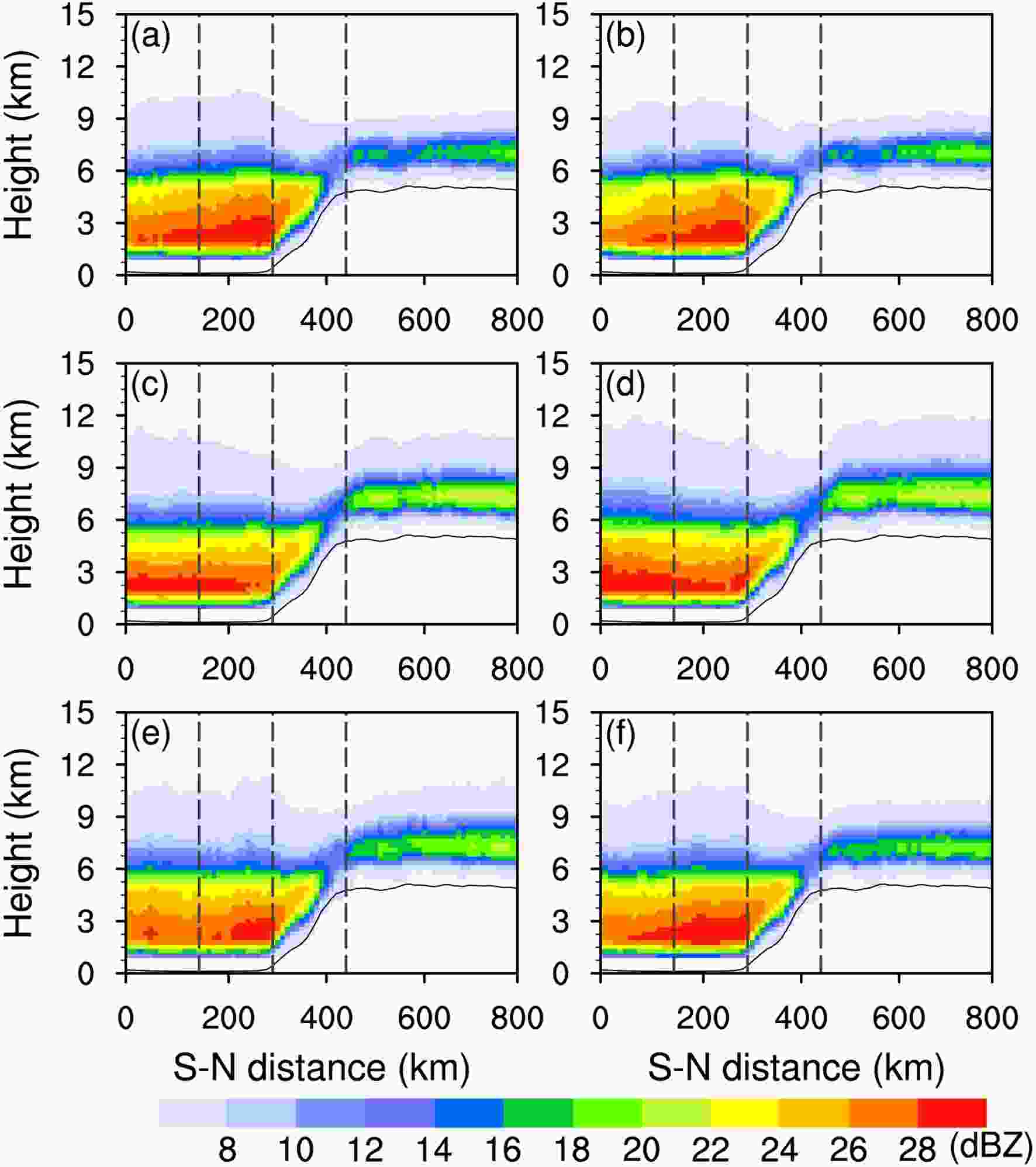

Figure9. Standardized amplitude (red dotted line) and percentage of variance explained by the diurnal harmonic (blue dotted line) for (a) RF, (b) RR, (c) STA, and (d) TB10.8. Gray solid lines represent the corresponding average altitude and long dashed black lines represent the boundary of each region.In order to analyze the variation of the vertical structure with terrain height, the vertical reflectivity distributions along the radial direction (south to north) in the study region are shown for the six periods in Fig. 10. The average radar reflectivity is lowest over HTPT, and the areas with echo intensity of more than 28 dBZ are mainly concentrated in FGP and FHH, with obvious diurnal variation characteristics. From midnight to morning (Fig. 10f, a, b), vertical movement over HTPT, SSSH, and FGP is weaker, with a reflectivity height of less than 10 km. Convection is weakest during early morning, with an average maximum reflectivity of less than 18 dBZ over HTPT. Furthermore, the strongest convection in the region occurs at FHH during this time, with reflectivity reaching 26 dBZ above 5 km. From afternoon to evening (Fig. 10d and e), moist convection is quick to develop over HTPT, SSSH, and FGP, and is most vigorous during the afternoon. The average radar echo height over HTPT reaches 12 km and the average maximum radar reflectivity reaches 22 dBZ. During this time, the reflectivity over FGP is strongest, exhibiting stronger reflectivity than the surrounding areas and featuring echo top heights of greater than 11 km. The vertical motion is weakest at FHH during this time, with 26-dBZ echo reflectivity occurring at heights less than 4 km.

Figure10. Average vertical reflectivity distribution in the radial direction along south to north in the study region in different periods: (a) early morning, (b) morning, (c) noon, (d) afternoon, (e) evening, and (f) midnight. Long dashed black lines represent the boundary of each region.

Figure10. Average vertical reflectivity distribution in the radial direction along south to north in the study region in different periods: (a) early morning, (b) morning, (c) noon, (d) afternoon, (e) evening, and (f) midnight. Long dashed black lines represent the boundary of each region.2

3.4. Diurnal variations of atmospheric circulation

Wind is an important factor influencing the diurnal variation of precipitation because it governs the transport and distribution of moisture (Bhatt and Nakamura, 2005; Chow and Chan, 2009; Zhang et al., 2018). The mean anomaly near-surface wind fields from daily averaged fields are shown in Fig. 11. A previous study has shown that the diurnal cycle of mountain-valley breezes strongly affects lower-level winds (Barros and Lang, 2003). At 0600 Universal Time Coordinate (UTC) (b) and 1200 UTC (c), HTPT exhibits topographically induced convergent heat flow with greater sensible heating than the surrounding areas because of the presence of a strong elevated heat source (Wu et la., 2007; Zhang et al., 2018). Because of this, the anomalous wind flows are directed toward HTPT from the surrounding regions. At the same time, the anomalous wind over SSSH exhibits an up-valley southwesterly flow, which is consistent with enhanced monsoonal flow and subsequent rainfall. Warm and moist flows from the Bay of Bengal converge at HTPT and SSSH through persistent orographic lifting which causes the moisture-laden air masses to cool and condense; hence, the RF and RR increase over HTPT. At 1800 UTC and 0000 UTC, the anomalous wind flows are directed away from HTPT toward the downslope regions because of the nocturnal radiational cooling known to occur over elevated terrain. The anomalous southwesterly flow over HTPT and SSSH reverses to a relatively arid, down-valley, northeasterly flow away from HTPT, which weakens the monsoonal circulation and rain. At the same time, the anomalous southeasterly wind is intensified at FFH, bringing in warm and moist air which is associated with the Asian summer monsoon. In addition, the destabilization of the atmosphere is maximized over the FHH at night because of the interaction between the increase in low-level moisture and the diurnal heating and cooling patterns of the atmosphere (Barros and Lang, 2003). These factors explain why the rainfall increases. Furthermore, at 0000 UTC, the anomalous northeasterly flow turns more southerly which may be related to the cool outflow from precipitation. This increases the down-valley tendency of winds (Barros and Lang, 2003). The anomalous southeasterly flows of the summer monsoon and a relatively arid northeasterly flow converge at FFH, which generates lift and precipitation at this location. The results show that the large-scale, near-surface circulation caused by HTPT and SSSH topography is an important component of the diurnal variations of precipitation. Figure11. Anomalous mean surface (0.995 sigma level) wind fields superimposed on elevation in the rainy season at (a) 0000, (b) 0600, (c) 1200, and (d) 1800 UTC. (The averaged anomalous variables at 0000, 0600, 1200, 1800 UTC were computed by subtracting the daily means, the same below.)

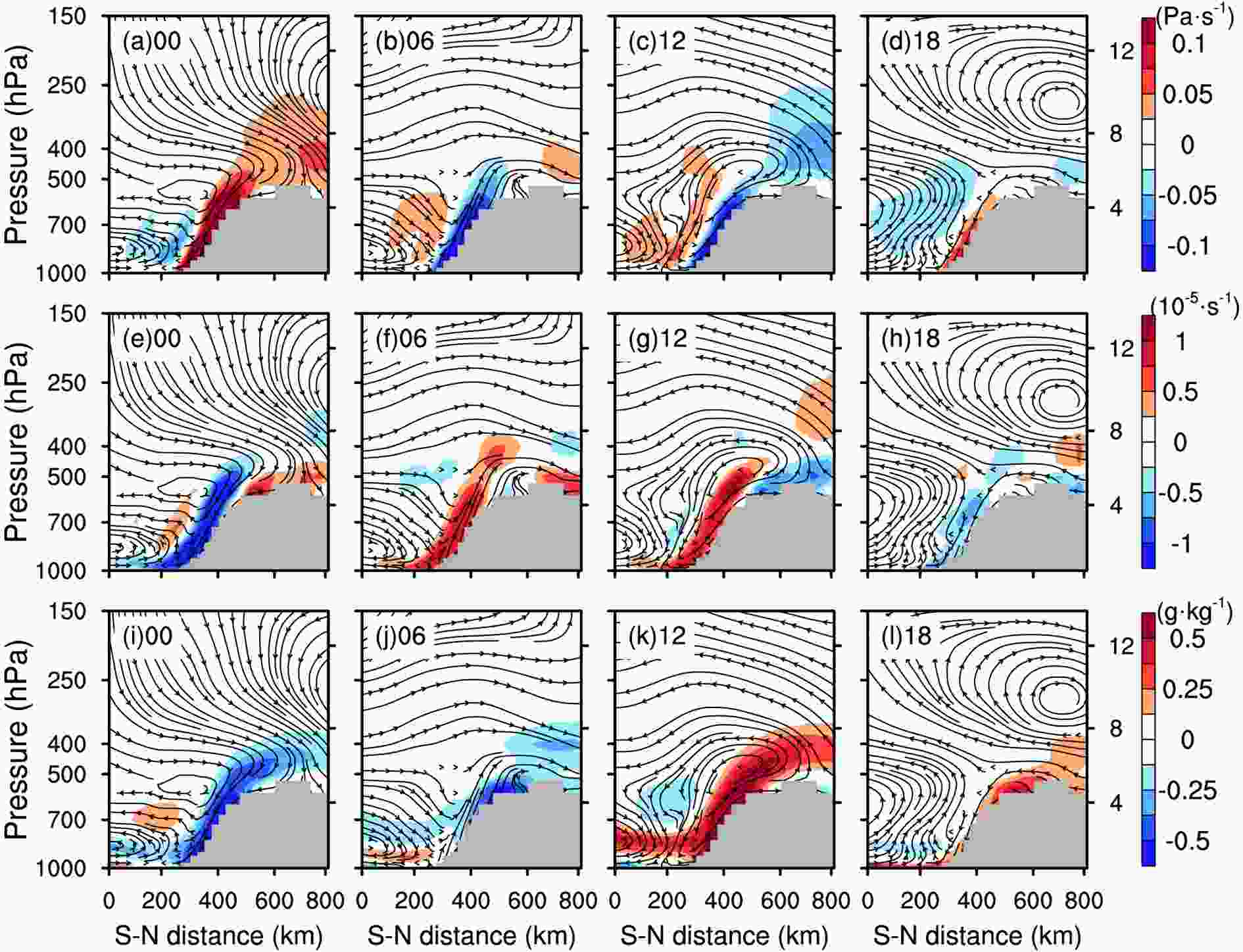

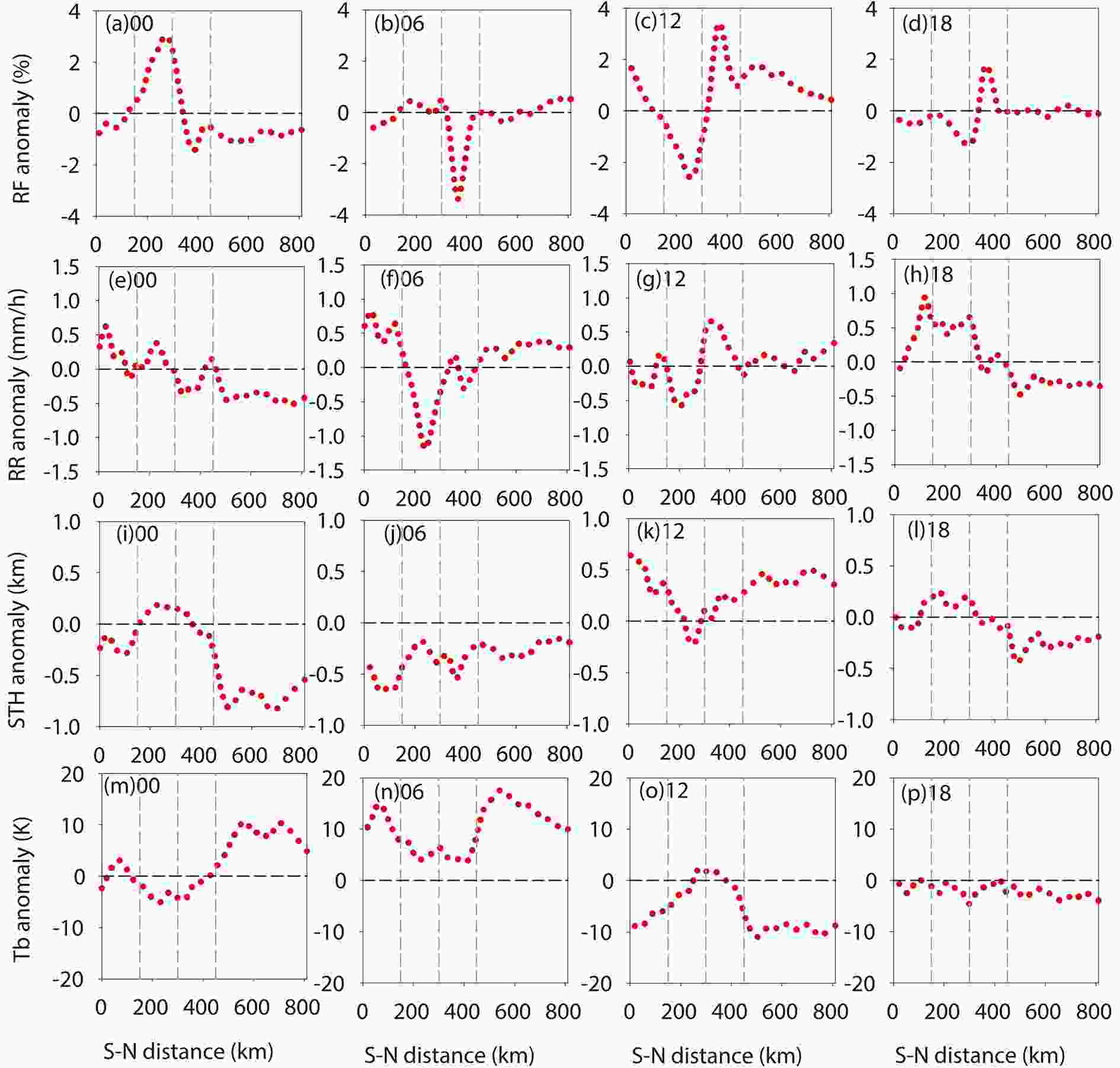

Figure11. Anomalous mean surface (0.995 sigma level) wind fields superimposed on elevation in the rainy season at (a) 0000, (b) 0600, (c) 1200, and (d) 1800 UTC. (The averaged anomalous variables at 0000, 0600, 1200, 1800 UTC were computed by subtracting the daily means, the same below.)To better understand the diurnal variations of precipitation over complex terrain, pressure-radial cross-sections of anomalous streamlines, vertical velocity, divergence and specific humidity at 0000, 0600, 1200, and 1800 UTC are presented in Fig. 12. The corresponding RF, RR, STA, and TB10.8 anomalies at the same times are shown in Fig. 13. The vertical motions exhibit apparent day-night changes, and the upward-downward motion patterns agree well with the precipitation distributions. Anomalous upward motions over HTPT are strongest and weakest at 1200 UTC and 0000 UTC, respectively, with 0600 UTC and 1800 UTC representing transition periods. At 0000 UTC, the surface cools over the HTPT, because of the nocturnal longwave radiative cooling effect (Ma et al., 2018).Consequently, strong anomalous downward motions occur over HTPT extending from the near surface to the upper troposphere (250 hPa, Fig. 12a). An anomalous divergent flow also occurs in the lower atmosphere (4–6 km), accompanied by a relatively weak anomalous convergent flow in the middle atmosphere (Fig. 13e), which is not conducive to the precipitation in this region, noted by a negative anomaly of RF (Fig. 13a), RR (Fig. 13e), and STA (Fig. 13i) and a positive anomaly of TB10.8 (Fig. 13m). Over SSSH, the anomalous vertical motions are downward with convergent flow and the rain is relatively weaker with negative RR. At the same time, the anomalous, down-valley wind transports arid air advected off the HTPT causing the specific humidity to decrease. However, over the FHH, the anomalous vertical motions are upward and are convergent due to the absence of up-valley flow (Barros and Lang, 2003). The low-level collision of the moist southerly air flow with the arid air flow, advected off HTPT, trigger convection at FHH, thereby contributing to the precipitation maximum with positive anomalies of RF, RR, and STA and a negative anomaly of TB10.8. At 0600 UTC, the anomalous, down-valley wind becomes an up-valley wind and the vertical motions over HTPT change from downward to upward. This reversal results from accumulative solar heating and subsequent warming through surface sensible heat flux, which causes strong local ascent and convective destabilization (Wu et al., 2007; Ma et al., 2018). The specific humidity begins to increase at HTPT (Fig. 12j), reaching a maximum at 1200 UTC (Fig. 12k).

Figure12. Pressure-radial cross-sections of anomalous streamlines and vertical velocity (top panel, shading), divergence (middle panel, shading), and specific humidity (bottom panel, shading) at 0000 UTC, 0600 UTC, 1200 UTC, and 1800 UTC, respectively.

Figure12. Pressure-radial cross-sections of anomalous streamlines and vertical velocity (top panel, shading), divergence (middle panel, shading), and specific humidity (bottom panel, shading) at 0000 UTC, 0600 UTC, 1200 UTC, and 1800 UTC, respectively. Figure13. RF (top panel), RR (second panel), STA (third panel) and TB10.8 (bottom panel) anomalies along the radial direction from south to north in the study region at 0000 UTC, 0600 UTC, 1200 UTC, and 1800 UTC, respectively. Long dashed grey lines represent the boundary of each region.

Figure13. RF (top panel), RR (second panel), STA (third panel) and TB10.8 (bottom panel) anomalies along the radial direction from south to north in the study region at 0000 UTC, 0600 UTC, 1200 UTC, and 1800 UTC, respectively. Long dashed grey lines represent the boundary of each region.At 1200 UTC, the anomalous upward motions over HTPT are strongest, extending from the near surface to the upper troposphere (~10 km, Fig. 12c). This results from the combined effects of anomalous convergent flow in the lower atmosphere and anomalous divergent flow in the middle to upper atmosphere (Fig. 12g). At the same time, the anomalous wind over FHH is an up-valley wind, which brings warm and moist air - into the region from the south, increasing the specific humidity and providing sufficient moisture for precipitation over HTPT (Fig. 12k). This circulation configuration is conducive for generating precipitation over HTPT with a strong positive anomaly of RF (Fig. 13c), RR (Fig. 13g), and STA (Fig. 13k) and a negative anomaly of TB10.8 (Fig. 13o). During this time, the anomalous downward motions at FHH reach a maximum with divergent flow near the surface, which is not conducive to precipitation, and the anomalies of RF, RR, and STA are negative. At 1800 UTC, the anomalous upward motions are suppressed, and an anticyclone is obvious at 7 km height over HTPT, weakening the precipitation. The anomalous winds over SSSH are weak and down-valley with convergent flow. The corresponding RF increases with positive specific humidity anomalies, but the intensity is weaker with zero anomalies.

Diurnal variations of precipitation exhibit significant regional differences that are strongly related to topography. The diurnal variations are most significant in the center of the TP and weakest at the boundary between each region. The most striking diurnal variable is RF. Rain parameters (RF, RR, and STA) over HTPT and FGP are characterized by afternoon maxima and morning minima due to the effect of accumulative solar heating, whereas, maximum rain parameters at FHH typically occur in the early morning. Rain parameters at SSSH are characterized by double peaks; one in the afternoon and one at midnight. The afternoon peak values mainly occur at higher altitudes whereas peak values at midnight typically occur at lower altitudes. Except for the daily peak of TB10.8 over FHH, which appears at noon, the peaks of TB10.8 occur approximately three hours after those of the other rain properties. This study only analyzes the daily variation characteristics of each parameter; however, the differences and relationships with diurnal variations between different parameters remain an interesting topic for future research.

Significant regional differences were also observed in the vertical structure of precipitation. Over HTPT and FGP, the convective activities are both strongest in the afternoon, exhibiting the thickest crystallization layer, and weakest in the early morning and morning, respectively. The collision and growth of precipitation particles at FGP is also most intense in the afternoon. Over FHH, the vertical structure of precipitation develops most vigorously from midnight to early morning with the most intense collision and growth of precipitation particles, whereas development is weakest at noon. Over SSSH, the vertical motions within the convective activity is stronger in the afternoon and at midnight with the strongest mixing of ice and water particles, and is shallowest in the morning. From FGP to SSSH, the bright band characteristics are more evident from midnight to morning, indicating a larger proportion of precipitating stratiform clouds.

The results of harmonic analysis showed that the peak daily variation of precipitation frequency occurs at 1600 LST over FGP and HTPT, then moves southward from SSSH to FHH from midnight to early morning; the phase exhibits significant southward movement characteristics, which may be related to the interaction between the systematic monsoon flow and the mountain-valley breezes. The daily variation characteristics of precipitation are most significant over HTPT, with the diurnal percentage variance reaching 90%.

Large-scale atmospheric circulation also exhibits obvious diurnal variation characteristics and corresponds well to the distribution of precipitation. At 0600 and 1200 UTC, HTPT exhibits topographically induced convergent, low-level, thermally contrasting flow with enhanced upward motions due to the strong heating effect over HTPT, which results in anomalous wind flows toward HTPT from the surrounding regions. The anomalous wind over SSSH is southwesterly, which is consistent with an enhanced monsoon circulation. Warm and humid air flow from the Bay of Bengal converges at HTPT and SSSH due to continuous topographic uplift, which increases the RF and RR over HTPT and SSSH. At 1800 and 0000 UTC, the anomalous wind flows away from HTPT toward the surrounding regions, and the anomalous upward motions change to downward flows because of the nocturnal cooling over elevated terrain. The anomalous southwesterly flow transits to a relatively arid northeasterly flow from HTPT, which counteracts the effect of the monsoon circulation on the transport of water vapor to the HTPT and SSSH. At 1800 UTC, the anomalous southeasterly wind intensifies in the foothills and precipitation over FHH begins to increase until 0000 UTC. As the anomalous northeasterly flow gets to the strongest, the weakest upward motion apparently occurs associated with the flow over the SSSH. The anomalous northeasterly flow also collides with the southeasterly flow over the FHH, which forms convergence and triggers moist convection and the maximum precipitation over there.

The diurnal variations of precipitation for different rain types and in different seasons will be studied in more detail based on the Global Precipitation Measurement data, which features relatively higher spatial and temporal resolutions. Moreover, the mechanism influencing the diurnal variation characteristics over the steep slopes of the Himalayas, such as the physical reasons for the southward movement of rain bands from lower elevations of SSSH to FHH from midnight to early morning will be further analyzed using high-resolution numerical models and additional observations.

Acknowledgements. This study was jointly funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant no. 41705011, 91837310), the National Key R&D Program of China (2018YFC1506803, 2018YFC1507302, 2018YFC1507200), and the Second Tibetan Plateau Scientific Expedition and Research (STEP) program (Grant No. 2019QZKK0104). We thank the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency and Goddard Space Flight Center for providing the TRMM PR 2A25 and VIRS 1B01 version 7 data.