HTML

--> --> -->Aerosols in the ambient environment commonly exist in the form of atmospheric particulate matter (PM), which is a compound of multiple minerals and materials originating from nature and anthropogenic emissions. Given different compounds, the climatic and environmental effects of aerosols are thus determined by both physical properties (e.g., particle size) and chemical constituents of PM (Pósfai and Buseck, 2010; Yang et al., 2011; Xin et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2018). It is known that mass concentrations of PM and chemical compositions are determined by many factors including primary emissions, chemical reactions, depositions, as well as meteorological conditions that control both local dispersion and long-range transport of PM (Yang et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2014, 2019). Measuring chemical components in PM is thus crucial for understanding the formation of atmospheric aerosols, especially the complex mechanisms behind frequently occurred haze pollution events (e.g., Wang et al., 2016, 2017, 2020).

Observational networks have been extensively established to monitor the physical, chemical, and optical properties of atmospheric aerosols worldwide, such as the Aerosol Robotic Network (AERONET) (Holben et al., 1998) and Global Atmosphere Watch: Aerosols (GAW) (WMO, 2001). Such networks provide ample observational data to help improve understanding of aerosol properties around the world. Similar networks were also established in China. In 2011, the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) launched the Campaign on Atmospheric Aerosol Research network of China (CARE-China). This is also the first comprehensive research platform for observing atmospheric aerosols in the country, aiming to provide in situ measurements of anthropogenic aerosol emissions to better understand the climatic and environmental effects of aerosols in China (Xin et al., 2015).

By taking advantage of such invaluable in situ measurements, complex atmospheric haze pollution mechanisms in China have been better elucidated (Guo et al., 2014; Huang et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2020). For instance, based on chemical data observed in representative mega cities across China, Yang et al. (2011) found that PM2.5 mass concentrations and chemical compositions varied substantially over space and that the observed severe PM2.5 pollution events in eastern China were largely attributable to local formation/production and regional transport of the secondary aerosols. Utilizing field measurements of aerosol properties at an urban site in Beijing during January and February 2015, Zamora et al. (2019) found that frequently occurring wintertime haze events in Beijing were attributable to the efficient nucleation and secondary aerosol growth under high gaseous precursor concentrations and stagnant air conditions. Likewise, by taking advantage of comprehensive measurements and modeling simulations, Huang et al. (2020) found that the haze events during the COVID-19 lockdown in eastern China were driven by the formation of substantial secondary aerosols due to increases in atmospheric oxidizing capacity.

Given the adverse effect on public health, PM2.5 mass concentration and its speciation have been extensively examined in the literature (Yang et al., 2011; Zamora et al., 2019). In the present study, emphasis is given to even finer aerosols with an aerodynamic size less than 1.0 μm, which is also known as submicron PM (abbreviated as PM1 hereafter). Given this smaller size, PM1 has higher extinction efficiency and larger negative health impacts (Shi et al., 2014). Therefore, evaluating the variability of PM1 and its chemical speciation in space and time is of great significance for understanding of its important roles in haze formation and visibility degradation.

By using three-year-long aerosol measurements that were sampled in six representative cities in China, here we aim to first examine variations in PM1 and its major chemical compositions in space and time, and then to explore their potential roles in the formation of severe fine particle pollution events. The following science questions are to be answered: (1) What chemical constituents were dominant factors in elevating PM1 pollution levels in the selected regions? (2) Was there a common mechanism for the formation of PM1 pollution events across these regions? and (3) Did meteorological conditions play important roles in modulating PM1 pollution levels?

2.1. Field campaign and instruments

In this study, aerosol measurements collected from the CARE-China network at six distinct regions during the period of 2012 to 2014 were used. These six sampling sites were deployed in different geographic regions representative of diverse emission types given different population size and urbanization levels. Table 1 gives a brief description of geographic location and the ambient background (rural or urban site) of these six sampling sites. Among them, the site over Qinghai Lake (abbreviated as QHL hereafter) is referred to as a background site since it was deployed in the Tibetan Plateau where it was less influenced by human activity. In contrast, the other five sites were all deployed in urban regions, thereby representing a pollution regime that was highly influenced by anthropogenic emissions (Ren et al., 2018).| Region | Longitude (°E) | Latitude (°N) | Location and property of monitoring sites |

| Qinghai Lake (QHL) | 101.32 | 37.62 | At the northwestern rim of Qinghai Lake and referred to as the rural background site |

| ürümqi (UMQ) | 87.68 | 43.77 | On the rooftop of a 10 m-high building on the campus of the Institute of Desert Meteorology at the urban center |

| Xi’an (XA) | 108.95 | 34.27 | On the rooftop of a 10 m-high building on the campus of the Institute of Earth Environment of CAS at the downtown area |

| Chengdu (CD) | 104.06 | 30.67 | On the rooftop of a 10 m-high building on the campus of Chengdu Institute of Plateau Meteorological at the urban center |

| Shanghai (SH) | 121.48 | 31.22 | On the rooftop of Shaw House on the campus of Fudan University in the city |

| Guangzhou (GZ) | 113.23 | 23.16 | On the rooftop of a 50 m-high building on the campus of the South China Institute of Environmental Science at the urban center |

Table1. Geolocation and ambient background information of six aerosol sampling sites used in this study. The abbreviation of each city/region was shown in brackets.

Size-segmented atmospheric PM was collected using nine-stage Anderson samplers (Anderson Series 20?800, United States) at an airflow rate of 28.3 L min–1 with cutoff sizes of 9.0, 5.8, 4.7, 3.3, 2.1, 1.1, 0.7 and 0.4 μm. Each set of aerosol samples were measured twice monthly, with every data collection task lasting for three days at five urban sites, while six days were used at the QHL site to guarantee an adequate number of valid samples. More detailed description of sampling collection and storage can be found in the literature like Ren et al. (2018) and Xin et al. (2015).

A DRI 2001 thermal/optical carbon analyzer was used to measure organic carbon (OC) and elemental carbon (EC) compositions in size-resolved particles at each sampling site by following the Interagency Monitoring of Protected Visual Environments (IMPROVE) thermal/optical reflectance (TOR) protocol (Chow et al., 2004, 2007). Meanwhile, soluble inorganic salts including five cations (Na+, NH4+, K+, Mg2+, and Ca2+) and three anions (Cl–,

In this study, PM with aerodynamic diameter no more than 1.1 μm were aggregated to represent PM1. Mass concentrations of PM1 and five major chemical compositions of OC, EC, sulfate (

2

2.2. Meteorological data

Meteorological conditions are believed to play important roles in modulating ambient PM concentrations other than primary emissions since they can modulate the dispersion and accumulation of PM (Zheng et al., 2017; An et al., 2019). Four primary meteorological factors that are highly associated with aerosol variations—air temperature (T), wind speed (WS), relative humidity (RH), and boundary layer height (BLH)—were hereby used. All these data were retrieved from the Meteorological Information Comprehensive Analysis and Process System (MICAPS), except BLH, which was retrieved from the ERA-Interim reanalysis that was provided by the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF). 3-h MICAPS data at the sampling sites were averaged for every 24-hour to approximate daily averages.2

2.3. Random forest

To better understand the haze formation mechanisms over the selected regions, we attempted to resolve statistical associations between PM1 and chemical species as well as meteorological factors at each individual site. The ultimate goal is to evaluate the relative importance of each factor contributing to PM1 loading levels to determine the leading influential factors in each city. The random forest (RF) method was hereby used to statistically link PM1 mass concentration to its five major chemical species and four meteorological factors. The reason to use the random forest method is twofold. First, RF has a good generalization performance. Second, in contrast to many “black-box” models, RF has a unique variable importance estimation capacity (Ho, 1998; Altmann, et al., 2010).The relative importance is calculated by estimating the response of out-of-bag error to the random permutation of out-of-bag data across each variable. Therefore, the larger the increase in error budget, the more important the variable. Such a metric is thus oftentimes used to assess the prediction power of the given predictor, enabling us to determine whether the given variable should be included in the modeling process or not. This capacity helps us better understand the intrinsic associations between the response variable and various explanatory factors (Bai et al., 2019a, b). For the configuration of RF models, 500 regression trees were used in each random forest model, while each tree was grown on a bootstrap sample with a random subset of predictors selected at each split. In this study, our focus is not on the RF modeling performance given limited samples (as large as of 72 data pairs given two monthly sampling frequency). Rather, we aimed to evaluate the relative importance of each explanatory variable, i.e., the relative contribution of chemical species and meteorological factors in determining PM1 mass concentration.

3.1. Major chemical species in PM1

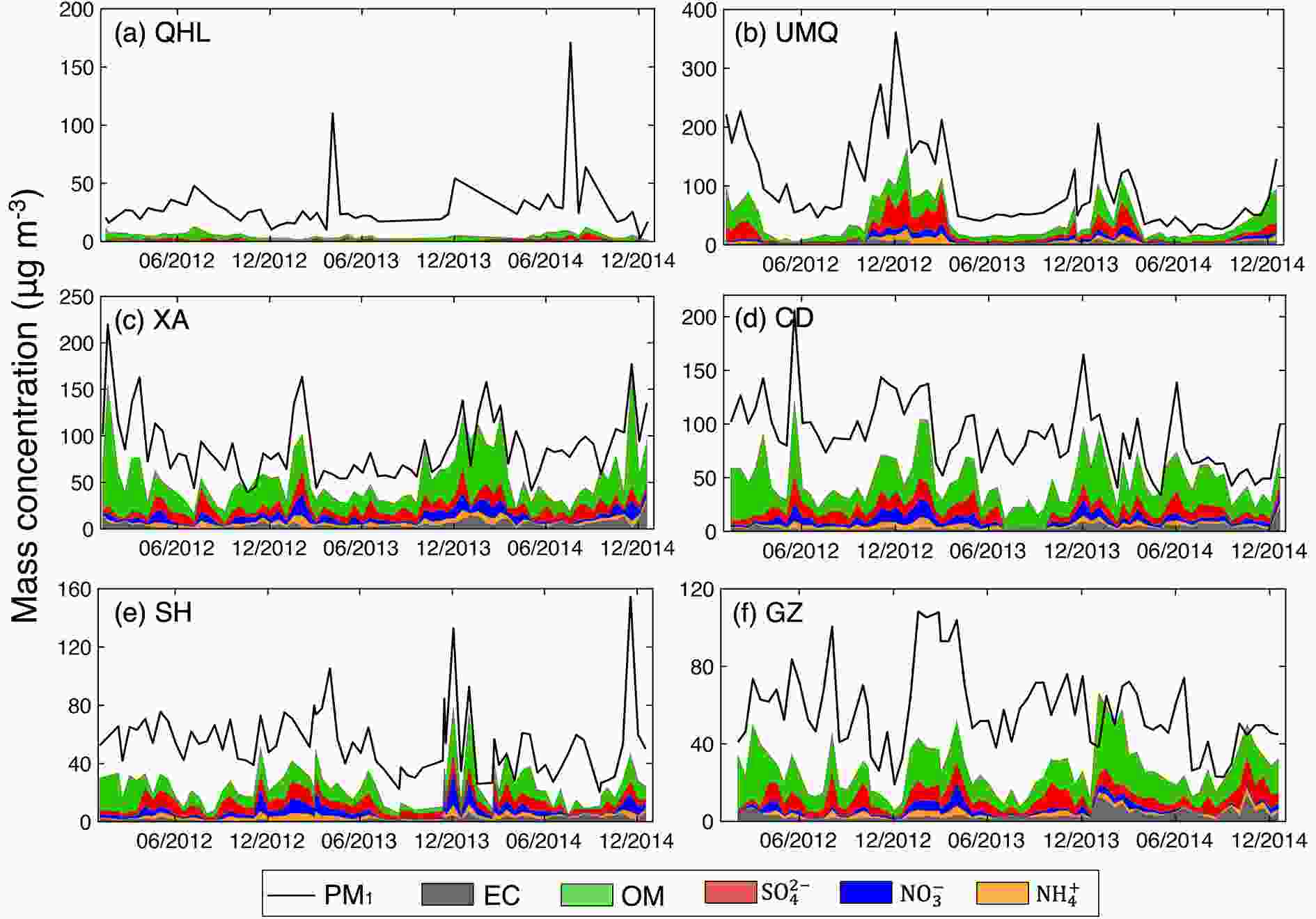

Figure 1 presents the temporal evolutions of PM1 and five major chemical constituents that were sampled at each individual site during the field campaign between 2012 and 2014. As shown, concentrations of PM1 and its chemical constituents varied significantly in space and time, with the maximum mean PM1 concentration being triple that of the minimum (29.5?98 μg m?3). Noteworthy is that there were two large outliers (>120 μg m?3) in the PM1 time series of QHL, and this could be due to possible measurement errors. According to the magnitude of mean PM1 concentration, these six sampling regions could be generally grouped into three primary pollution regimes as clean (QHL: 29.5±25.1 μg m?3), polluted (SH and GZ: 54.2±23.3 and 57.3±20.9 μg m?3), and severely polluted (XA, CD, and UMQ: 88.1±34.7, 89.7±32.1, and 98±69.5 μg m?3), respectively. Temporally, PM1 varied even more drastically, as high PM1 loading (>100 μg m?3) appeared mainly in the winter, whereas low values were seen in the summer. Meanwhile, high PM1 concentrations were oftentimes accompanied by a substantial increase in chemical constituents such as organic aerosols, sulfates and nitrates, revealing the significance of secondary aerosols in elevating ambient PM1 loading. Figure1. Temporal evolution of PM1 mass concentration and five major chemical compositions sampled in six representative cities in China between 2012 and 2014. Note that there were only 53 valid samples measured at the QHL site during the field campaigns.

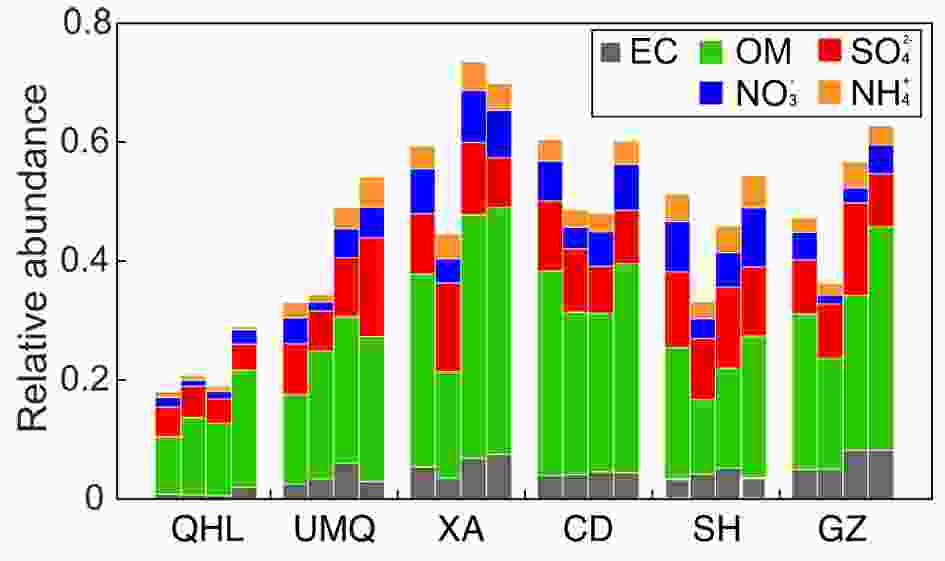

Figure1. Temporal evolution of PM1 mass concentration and five major chemical compositions sampled in six representative cities in China between 2012 and 2014. Note that there were only 53 valid samples measured at the QHL site during the field campaigns.In order to better reveal the spatial and temporal variability of chemical constituents in PM1 in these six regions, we compared the seasonal mean relative fraction of each chemical species in PM1. The results are presented in Fig. 2. It is seen that total carbon (OC plus EC) and SNA (the sum of sulfate, nitrate, and ammonium) only accounted for a small portion (<50% in most regions) of PM1 mass concentration, especially at the QHL site (21.4%). Given low primary emissions around the QHL site due to limited human activity, the low fraction of five major chemical constituents thus implies higher contribution of other components like mineral elements from manmade or natural primary sources to the observed PM1 mass concentration. However, noteworthy is that the mean PM1 concentration at the QHL site is even larger than some urban sites around the world, e.g., Vienna (14.9±7.7 μg m?3) (Gomi??ek et al., 2004). Due to the data availability issue, the element analysis was not performed here to better examine the constituents of PM1 at the QHL site; hence, reasons for this effect remain unclear.

Figure2. Seasonal mean relative abundance of five major chemical compositions in PM1 mass sampled at six representative cities during the 2012?14 field campaigns. Bars from the left to the right for each city indicate the fraction of chemical compositions in spring (MAM), summer (JJA), autumn (SON), and winter (DJF), respectively. Note that only 53 observations were sampled in Qinghai from the field campaigns.

Figure2. Seasonal mean relative abundance of five major chemical compositions in PM1 mass sampled at six representative cities during the 2012?14 field campaigns. Bars from the left to the right for each city indicate the fraction of chemical compositions in spring (MAM), summer (JJA), autumn (SON), and winter (DJF), respectively. Note that only 53 observations were sampled in Qinghai from the field campaigns.An inter-comparison between five chemical constituents revealed that OM had the most significant contribution to PM1 mass concentration since OM alone accounted for a mass fraction as large as of 10%?42% of PM1 throughout the year at these six sampling sites. Such a high fraction of OM was also found in other cities like Beijing and Tianjin (Shao et al., 2018; Khan et al., 2021). Temporally, this high fraction was even more impressive in the autumn and winter, particularly in cities like Xi’an and Guangzhou where OM increased more drastically during the wintertime than in the summer. This could be attributable to extensive primary emissions from biomass burning and coal combustion in the winter (Li et al., 2014; Wu et al., 2020). In Guangzhou, the increase in OM could be ascribed to both primary and secondary organic aerosols from extensive traffic emissions (e.g., vehicles and ships), since the primary organic pollutants can be easily oxidized to form SOA through gas-phase oxidation chemistry in a wet ambient environment (Yang et al., 2011; Qin et al., 2017).

The SNA only accounted for 7%?23% (a mean value of 17.8%±5.9%) of PM1 concentration. Notably, sulfate constituted much higher fractions (58%±6.6% of the SNA) than the other two counterparts (25.6%±4.3% for nitrate and 16.4%±3% for ammonium). In contrast, the EC constituted a much lower fraction with a percentage ranging from only 0.9%?6.5%. Spatially, Guangzhou had the largest EC fraction (6.5%) while the smallest fraction (<1%) was observed at the QHL site. Since the field measurements at the QHL were considered as the ambient background values, these inter-comparation results collectively imply that the higher PM1 mass concentration in the other five major cities could be attributable largely to extensive anthropogenic emissions from primary sources like vehicles and heating related biomass and coal combustion.

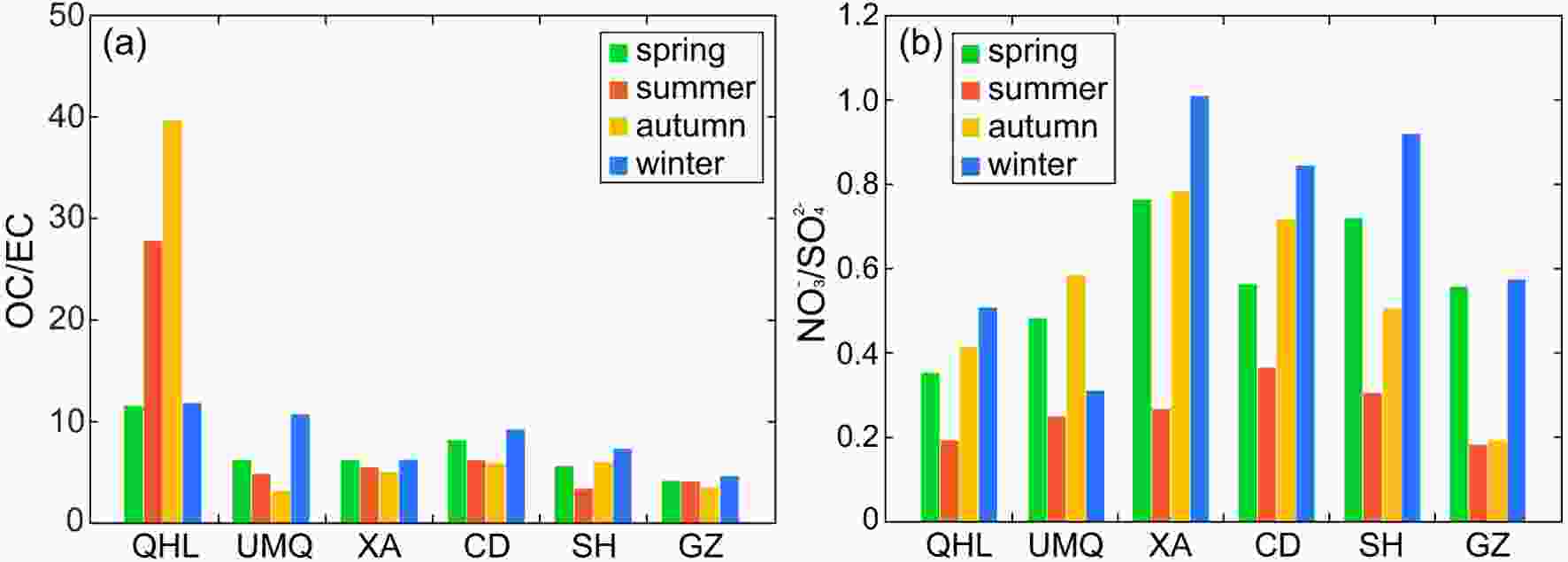

Figure 3 compares the seasonal mean mass ratio of OC to EC (OC/EC) and

Figure3. Same as in Fig. 2 but for seasonal mean mass ratios of (a) OC to EC and (b)

Figure3. Same as in Fig. 2 but for seasonal mean mass ratios of (a) OC to EC and (b)

The mass ratio of

The

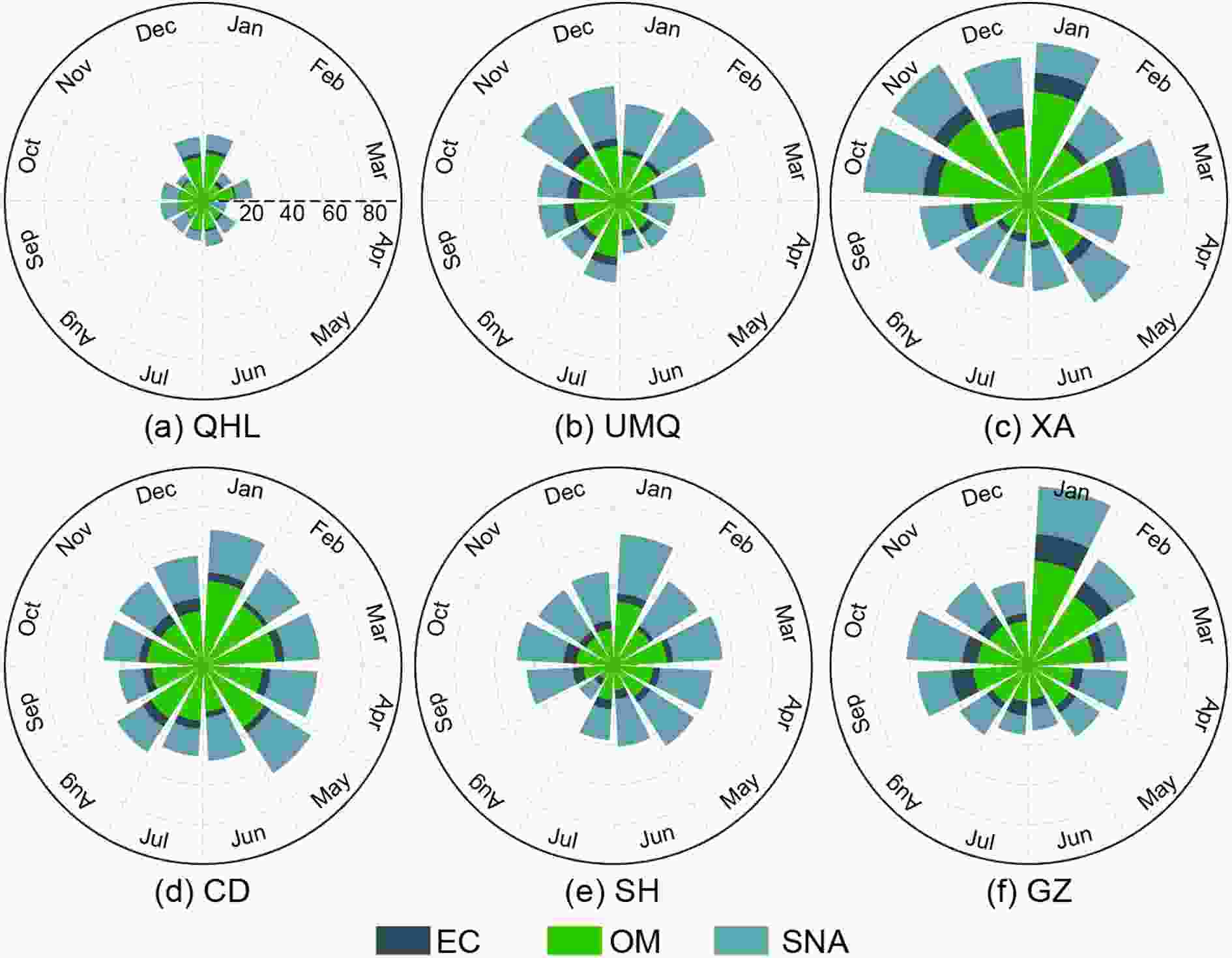

Figure 4 compares the annual cycle of EC, OM, and SNA in PM1 mass in these six representative regions. Noteworthy is that the sum of EC, OM, and SNA at QHL only accounted for <30% of PM1 mass throughout the year, except in December and January, when there was a marked increase in OM. Nevertheless, the average ratio was still low (24.7%), even after accounting for other inorganic ions such as K+, Na+, Ca2+, Mg2+, Cl?, and F?. This implies the species considered in this study were insufficient to account for PM1 mass measured at QHL. Conversely, the sum of EC, OM, and SNA constituted more than 80% of PM1 mass during wintertime in Guangzhou (January) and Xi’an (October, November, and January), especially the latter two components (i.e., OM and SNA), accounting for the vast majority of wintertime PM1 mass concentration. Overall, the largest fraction was more likely to be observed in January due to a substantial increase in OM and SNA, particularly OM, which increased from about 20% in December to nearly 50% in January in Guangzhou (Fig. 4f). These results clearly revealed significant variations in PM1 and its speciation in space and time, highlighting the importance of continuous field campaigns, particularly a comprehensive analysis of elements, to better understand the variability of chemical compositions in PM1 across China.

Figure4. Monthly mean relative abundance of elemental carbon (EC), organic mass (OM), and secondary inorganic species (denoted as SNA, which is represented by the sum of sulfate, nitrate, and ammonium) in PM1 mass at six cities across China during 2012?14. A commonly applied factor of 1.4 was applied to convert organic carbon to OM to account for unmeasured atoms in organic species. Note that observations at the QHL station were temporally discontinuous during the field campaigns due to the absence of valid measurements in several months.

Figure4. Monthly mean relative abundance of elemental carbon (EC), organic mass (OM), and secondary inorganic species (denoted as SNA, which is represented by the sum of sulfate, nitrate, and ammonium) in PM1 mass at six cities across China during 2012?14. A commonly applied factor of 1.4 was applied to convert organic carbon to OM to account for unmeasured atoms in organic species. Note that observations at the QHL station were temporally discontinuous during the field campaigns due to the absence of valid measurements in several months.2

3.2. Chemical compositions during clean and polluted days

To better examine the associations between chemical compositions and PM1 mass concentrations, particularly their relative roles in elevating PM1 loading levels, we compared mass concentration of each major chemical composition in PM1 at each sampling location between distinct pollution episodes. We define clean and polluted episodes according to the relative levels of PM1 mass concentration in each specific region as days with the smallest and the largest 20% of PM1, respectively. Detailed comparison results were presented in Table 2.| Region | Episode | PM1 | EC | OM | $ {\rm{NO}}_{3}^{-} $ | $ {\rm{SO}}_{4}^{2-} $ | $ {\rm{NH}}_{4}^{+} $ |

| Qinghai (N=12) | clean | 13.96±4.57 | 0.12±0.10 | 2.03±1.52 | 0.33±0.13 | 0.77±0.53 | 0.14±0.21 |

| polluted | 59.64±43.40 | 0.21±0.20 | 4.03±3.05 | 0.34±0.22 | 2.06±1.86 | 0.33±0.31 | |

| ürümqi (N=14) | clean | 35.29±6.86 | 1.74±0.72 | 9.19±2.17 | 0.76±0.73 | 3.14±1.19 | 0.70±0.48 |

| polluted | 213.76±51.35 | 4.62±3.47 | 40.63±14.60 | 8.26±4.89 | 29.70±17.08 | 8.32±5.71 | |

| Xi’an (N=15) | clean | 52.15±7.19 | 3.20±2.19 | 18.72±7.74 | 3.72±2.28 | 6.85±3.43 | 2.30±0.99 |

| polluted | 142.29±29.75 | 7.46±6.75 | 61.14±29.07 | 12.47±5.97 | 12.43±6.50 | 6.25±3.13 | |

| Chengdu (N=14) | clean | 50.44±8.78 | 3.11±1.65 | 17.78±5.23 | 3.07±1.43 | 5.34±2.51 | 1.73±0.79 |

| polluted | 138.41±23.36 | 3.89±2.00 | 45.66±14.98 | 10.32±5.33 | 12.70±6.33 | 5.23±2.62 | |

| Shanghai (N=14) | clean | 28.85±4.49 | 2.05±1.34 | 5.38±3.63 | 1.58±1.51 | 4.40±1.64 | 1.38±0.71 |

| polluted | 88.33±25.72 | 2.12±1.70 | 15.98±8.53 | 9.79±5.47 | 9.07±2.50 | 4.39±1.50 | |

| Guangzhou (N=14) | clean | 30.91±7.55 | 2.54±2.07 | 9.23±6.28 | 0.73±0.38 | 3.10±1.20 | 0.70±0.35 |

| polluted | 87.34±14.81 | 2.93±1.63 | 17.73±7.16 | 3.53±2.81 | 7.72±3.56 | 2.64±1.21 |

Table2. Comparisons of mean mass concentration of PM1 and chemical compositions (units: μg m?3) during clean and polluted episodes. Here clean and polluted days were defined as days with the lowest and the largest 20% PM1 mass concentration during the study time period, respectively. N denotes the number of samples in each episode and uncertainty of each factor was characterized by plus and minus one standard deviation from the mean value.

It is found that PM1 concentration on polluted days was, on average, 2.6~6.5 times the magnitude of that during clean periods, with the largest increase observed in ürümqi (6.5), followed by Qinghai (4.6), Shanghai (3.1), Guangzhou (2.8), Chengdu (2.7), and Xi’an (2.7). This also implies PM1 concentration in ürümqi experienced the most significant variation over the time covered by the sampling period. On the contrary, PM1 concentration in Chengdu exhibited a relatively low variability throughout the year. In regard to chemical constituents, the mass concentration of some species during polluted episodes increased by a factor as large as 10 times of that during clean episodes.

During polluted periods, in Qinghai, sulfate almost tripled in concentration compared to that on clean days, while OM, EC, and ammonium doubled their concentrations. In contrast, nitrate maintained a nearly constant concentration. This implies the high PM1 concentration at QHL was dominated by primary combustion emissions, since emissions from vehicles were negligible around the sampling region. In ürümqi, there were substantial increases in concentrations of five major chemical compositions as ammonium, nitrate, sulfate, OM, and EC increased by a factor of 11.9, 10.9, 9.5, 4.4, 2.7, respectively. Such a salient increase in these five major compositions inevitably elevated the mass concentration of PM1. Given the considerable increase in concentrations of SNA, we may largely ascribe the drastic elevation in PM1 mass concentration during polluted days in ürümqi to extensive anthropogenic primary emissions. On the other hand, this also could be attributable to enhanced nitrate formation as well as aerosol hygroscopicity due to increased RH during wintertime in ürümqi resulting from extensive snowfalls, since a similar effect was also observed in north China (Shao et al., 2018; Sun et al., 2020).

Xi’an and Chengdu, two inland mega cities, were found to exhibit similar variations in concentrations of both PM1 and major chemical compositions. Moreover, their data magnitudes were also comparable. Specifically, PM1 concentration on polluted days in both cities was 2.7 times of that on clean days. In terms of the five major chemical constituents studied, Xi’an had larger concentrations of EC, OM, nitrate, and ammonium than Chengdu during polluted episodes, especially the former two species as their concentrations in Xi’an significantly exceeded those in Chengdu. These results suggest that primary emissions played a more important role in elevating PM1 pollution levels in Xi’an, whereas PM1 pollution in Chengdu could be attributable to larger emissions from stationary sources (e.g., coal combustion) given higher sulfate loading.

The two mega cites in the coastal regions, Shanghai and Guangzhou, were both found to suffer from similar PM1 pollution levels given comparable mean PM1 concentration. It is indicative that PM1 concentration during polluted days almost tripled that on clean days in both cities. During polluted episodes, concentration of all species except EC was observed to increase significantly in both cities. Noteworthy is that all the remaining four major species were found to increase even more markedly in Shanghai, especially OM (+10.6 μg m?3) and nitrate (+8.2 μg m?3). This implies more important roles of mobile sources in elevating PM1 pollution levels in Shanghai during haze days. Similar results have also been revealed in the literature (e.g., Shi et al., 2014; Qiao et al., 2016).

Compared to the other four species, EC constituted a relatively low fraction in urban areas. Also, the absolute concentration exhibited small variation between two regimes. This indicates that the phenomenal increase in PM1 concentration during polluted days should be attributable more to other species such as OM, nitrate and sulfate as their concentrations were found to increase drastically. This finding also corroborates the critical role of the fast formation of secondary aerosols via aqueous reaction in exacerbating regional fine particle pollution levels during polluted periods (Wang et al., 2017, 2019; Yao et al., 2018; Dang and Liao, 2019).

In light of the increases in mean concentrations of PM1 and five major chemical species, we find that mean PM1 concentration had increased by 45~178 μg m?3 during polluted periods compared to that on clean days (Table 2). However, the accumulated increases in concentration of the five major chemical constituents only accounted for a small fraction of the total increased PM1 concentration. This implies that the observed high PM1 loading also should be attributable to factors other than these five major chemical constituents. In other words, it is challenging to resolve PM1 pollution mechanisms simply based on these five chemical species since they only accounted for a small fraction of the observed increase in PM1 concentration.

Since severe haze pollution events are oftentimes observed in the winter, we further compared mass concentrations of PM1 and five major chemical constituents during polluted days in winter and other seasons. As shown in Table 3, higher mean PM1 concentration was observed during wintertime in Xi’an, Shanghai, and Guangzhou. In ürümqi, there was a noticeable increase in concentration of OM, sulfate, and ammonium in the winter, especially OM (+12.61 μg m?3) as the mean wintertime concentration was 1.5 times of that in other seasons. This implies more extensive primary emissions in ürümqi in the winter and that the elevated OM could be attributable to wetter weather due to extensive wintertime snowfalls that boost the formation of SOA.

| Region | Season | N | PM1 | EC | OM | $ {\rm{NO}}_{3}^{-} $ | $ {\rm{SO}}_{4}^{2-} $ | $ {\rm{NH}}_{4}^{+} $ |

| Qinghai | winter | 1 | 54.26 | 0.10 | 5.20 | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.01 |

| others | 10 | 60.18±45.71 | 0.22±0.20 | 3.91±3.19 | 0.37±0.20 | 2.26±1.83 | 0.36±0.31 | |

| ürümqi | winter | 10 | 209.51±59.02 | 3.76±3.50 | 44.47±13.91 | 7.31±3.82 | 29.88±11.81 | 8.43±4.82 |

| others | 5 | 210.86±35.85 | 5.68±3.31 | 31.86±11.47 | 10.47±6.07 | 28.23±25.28 | 8.33±7.34 | |

| Xi’an | winter | 9 | 144.95±32.61 | 9.10±7.92 | 59.46±27.59 | 12.69±6.18 | 13.00±7.64 | 6.87±3.27 |

| others | 6 | 138.30±27.30 | 4.99±3.88 | 63.65±33.70 | 12.13±6.20 | 11.57±4.83 | 5.32±2.92 | |

| Chengdu | winter | 7 | 132.99±16.78 | 3.30±2.60 | 41.96±16.02 | 12.23±5.20 | 12.40±4.98 | 6.16±2.83 |

| others | 8 | 139.46±29.44 | 4.05±1.54 | 45.47±17.04 | 8.43±4.72 | 12.63±7.35 | 4.30±2.05 | |

| Shanghai | winter | 4 | 92.98±28.21 | 3.11±2.76 | 24.57±11.27 | 13.35±7.38 | 9.80±2.67 | 5.45±1.78 |

| others | 9 | 84.90±25.22 | 1.75±0.97 | 12.26±3.99 | 7.90±4.21 | 8.98±2.48 | 3.92±1.18 | |

| Guangzhou | winter | 4 | 99.14±16.10 | 2.17±0.28 | 18.40±4.45 | 4.82±0.43 | 7.59±2.37 | 3.13±0.84 |

| others | 10 | 84.19±12.41 | 3.30±1.90 | 18.29±8.05 | 3.22±3.30 | 7.98±4.17 | 2.58±1.32 |

Table3. Same as in Table 2 but for comparisons of mean mass concentration of PM1 and chemical compositions (units: μg m?3) during polluted days in winter and other seasons. Note that there is only one valid sample in Qinghai during the winter.

In Xi’an, all five major chemical compositions were found to have larger mass concentration during the wintertime except OM, especially EC (+4.01 μg m?3), implying the wintertime PM1 pollution in Xi’an could be ascribed to more extensive primary emissions. In contrast, both PM1 and the five major chemical constituents were observed to have higher concentration in Chengdu during the wintertime, with the most significant increase found in OM (+12.31 μg m?3), followed by nitrate (+5.45 μg m?3), ammonium (+1.53 μg m?3) and EC (+1.36 μg m?3). This could be due to the enhanced formation of secondary aerosols during the wintertime. In contrast, little difference was observed in chemical compositions between seasons in Guangzhou. Noteworthy is that there was a ubiquitous increase in ammonium during wintertime in these five major cities, though the magnitude was relatively small. These diverse results clearly highlight the complexity behind the formation mechanism of PM1 pollution events as factors like the formation of SOA and aerosol hygroscopicity could all result in a significant increase in PM1 loading in the atmosphere (Khan et al., 2021).

2

3.3. Impact of meteorological conditions on PM1 pollution

In addition to chemical speciation, PM1 mass concentration was modulated by meteorological conditions, which are believed to play an important role in governing the dispersion of atmospheric particles and its gaseous precursors. Figure 5 shows the correlation between PM1 mass concentration and the four meteorological factors of air temperature, wind speed, RH, and BLH, respectively. Figure5. Correlation between PM1 mass concentration and four meteorological factors in six representative regions across China. Only data values during clean (circle) and polluted (diamond) days were extracted for the calculation of correlation coefficient. Correlation values marked by asterisk indicate the correlation is statistically significant at the 95% confidence interval.

Figure5. Correlation between PM1 mass concentration and four meteorological factors in six representative regions across China. Only data values during clean (circle) and polluted (diamond) days were extracted for the calculation of correlation coefficient. Correlation values marked by asterisk indicate the correlation is statistically significant at the 95% confidence interval.Negative correlations were observed between PM1 mass concentration and air temperature (except at the QHL where exhibited a positive correlation), especially in ürümqi, Xi’an, and Shanghai, where negative correlations were even statistically significant at the 95% confidence interval. High PM1 concentrations were mainly observed during cold days, whereas low values were prevalent on hot days. This effect was even more pronounced at ürümqi and Xi’an, in large part possibly due to the wintertime heating-related extensive coal combustion in these two cities. In addition, stagnant weather was more likely to occur in the winter, which can also elevate PM1 loading (Shao et al., 2018). For regions like Guangzhou, temperature appeared to have no significant association with PM1 concentration. This is because temperature is normally high in Guangzhou throughout the year and there is almost no extensive wintertime heating related coal combustion there.

Wind speed exhibited a negative correlation with PM1 mass concentration in the five major cities (Fig. 5b), which is also in line with our expectation, since wind modulates the diffusion and transport of regional air pollutants. Nevertheless, significant correlations were found only in ürümqi and Chengdu, indicating wind played critical roles in modulating regional PM1 concentration levels in these two cities.

Humidity is also a critical factor since it determines the nucleation and hygroscopic growth of particles through gas-liquid reaction process, especially the aqueous-phase oxidation of SO2 (Wang et al., 2016, 2020; Li et al., 2017; Zheng et al., 2017; Sun et al., 2020). Given the complex process of gas-liquid reaction, the relationship between humidity and PM1 mass concentration is oftentimes nonlinear and nonstationary, making it challenging to characterize the statistical associations between them. A statistically significant positive correlation was found between RH and PM1 in ürümqi, with high pollution levels being more likely to be observed under wetter conditions with RH > 70% (Fig. 5c). A recent study also revealed distinct responses of primary and secondary species in PM1 and PM2.5 to RH due to changes in aerosol hygroscopicity and phase states (Sun et al., 2020).

BLH is another key factor modulating the dispersion and accumulation of air pollutants in the troposphere in addition to wind speed (Guo et al., 2019; Lou et al., 2019), since a low planetary boundary layer can suppress the vertical and horizontal diffusion of aerosol, in turn exacerbating the haze pollution (Liu et al., 2018; Miao et al., 2018; Zhu et al., 2018; Bai et al., 2019a). Negative correlations were found between BLH and PM1 mass concentration in five major cities, with statistically significant correlations (95% confidence interval) observed in ürümqi (R = –0.35), Xi’an (R = –0.48), and Shanghai (R = –0.58), respectively. It is understood that severe haze pollution events oftentimes are accompanied by a low BLH (<200 m), causing both fine particles and precursors to be suppressed in the lower troposphere near the ground, and accelerating the accumulation of air pollutants and higher PM1 loading in turn.

Table 4 compares the seasonal mean meteorological conditions during polluted days between winter and other seasons. The results indicate that there were significant yet heterogeneous differences in meteorological conditions between distinct seasons. Generally, the synoptic weather in the winter was oftentimes cold, calm (lower wind speed), along with a low BLH, and even wetter in some regions (e.g., ürümqi, Chengdu, and Shanghai). Evidently, such a weather condition is favorable to the accumulation of air pollutants (low wind speed and BLH) and the formation of secondary aerosols (cold and wet) (Li et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2017; An et al., 2019). Noteworthy is that synoptic weather appears to have little effect on PM1 pollution levels in Chengdu despite the similarity in PM1 concentration and meteorological conditions (except temperature) across seasons. This could be attributable to the basin topography of Chengdu, where air pollutants cannot be easily diluted under a relatively calm weather regime, thereby yielding a near constant ambient PM1 loading therein.

| Region | Season | N | T (°C) | WS (m s?1) | RH (%) | BLH (m) |

| Qinghai | winter | 1 | ?9.39 | 0.96 | 54.39 | 34.12 |

| others | 10 | 9.97±6.07 | 1.68±0.59 | 64.60±23.67 | 89.00±51.85 | |

| ürümqi | winter | 10 | ?11.40±1.84 | 1.72±0.26 | 77.09±3.95 | 20.19±7.60 |

| others | 5 | 5.78±10.88 | 2.18±0.71 | 49.57±25.62 | 22.96±7.15 | |

| Xi’an | winter | 9 | 1.46±1.64 | 1.89±0.81 | 58.13±24.97 | 66.16±78.29 |

| others | 6 | 9.98±5.94 | 2.40±1.22 | 70.17±7.36 | 95.47±100.10 | |

| Chengdu | winter | 7 | 7.25±2.34 | 1.13±0.20 | 76.84±4.25 | 124.74±91.37 |

| others | 8 | 15.55±5.85 | 1.05±0.20 | 74.51±6.40 | 143.80±124.95 | |

| Shanghai | winter | 4 | 5.65±3.84 | 2.10±0.90 | 64.95±3.20 | 209.68±190.34 |

| others | 9 | 15.04±4.99 | 2.74±0.93 | 61.93±9.06 | 319.77±176.29 | |

| Guangzhou | winter | 4 | 17.16±3.89 | 1.95±0.54 | 75.06±10.82 | 154.09±103.69 |

| others | 10 | 22.56±5.21 | 2.35±0.69 | 82.92±8.82 | 350.48±128.09 |

Table4. Same as in Table 3 but for meteorological conditions. Note that there is only one valid sample in Qinghai during the winter.

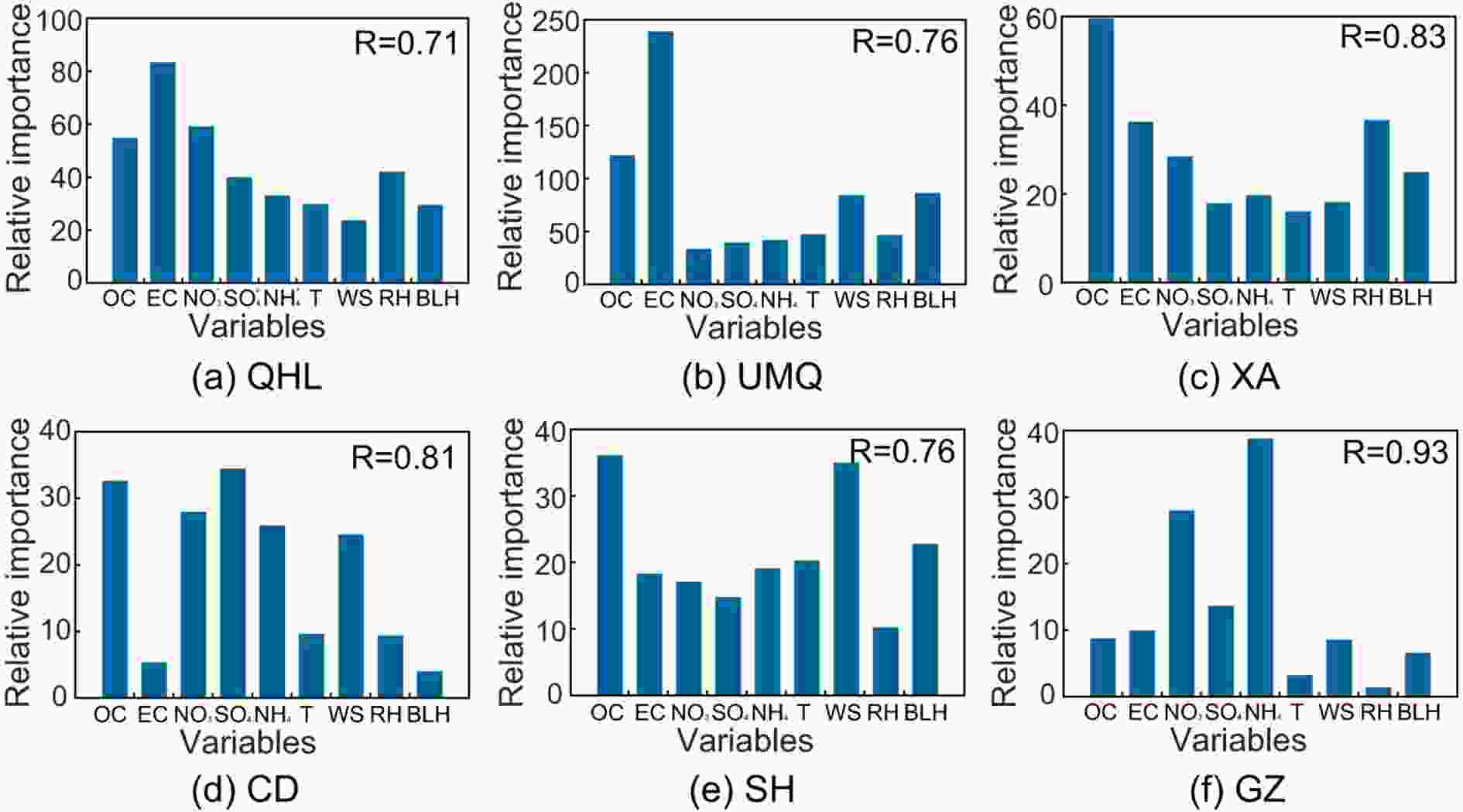

Figure 6 compares the relative importance of each factor in predicting PM1 concentration levels at each individual sampling site. As shown, leading factors (i.e., factors with larger relative importance) differed across study regions. Specifically, EC was the leading factor in predicting PM1 mass concentration at the QHL, implying the variability of PM1 concentration was highly associated with the loading of EC. Since this region was deemed as the ambient background given limited human activity, it is reasonable to conclude that PM1 loading in this region is largely modulated by EC from primary emissions occurring there. In ürümqi, EC and OC were found to play more important roles, indicative of larger contribution of primary sources to PM1 variations in this region.

Figure6. Relative importance of five primary chemical constituents and four related meteorological factors contributing to the observed PM1 mass concentration during polluted days. R denotes the correlation coefficient between predicted PM1 mass concentration values and the corresponding in situ observations.

Figure6. Relative importance of five primary chemical constituents and four related meteorological factors contributing to the observed PM1 mass concentration during polluted days. R denotes the correlation coefficient between predicted PM1 mass concentration values and the corresponding in situ observations.In Xi’an, OC played the predominant role compared to other factors, followed by RH, EC, and nitrate. This is indicative of the significant role of secondary aerosols in modulating PM1 mass concentration there. In contrast, OC and SNA played comparable roles in Chengdu, followed by wind speed. Among them, sulfate had a larger importance than the others, implying more important roles played by stationary sources. Moreover, wind was also a key factor in modulating the dispersion of PM, since air pollutants cannot be easily diluted in Chengdu due to the basin topography. In Shanghai, OC and wind speed were two leading factors, followed by BLH, indicating the critical role of secondary aerosols and meteorological conditions like temperature inversion in modulating PM1 concentration in this region.

In spite of the low abundance of ammonium and nitrate as compared to other three species, these two species were found to play the most critical roles in modulating the variations in PM1 mass concentration in Guangzhou (Fig. 6f). Conversely, RH was found to play the least important role, because Guangzhou is located in Pear River estuary, which has a humid subtropical climate, thereby the humidity is high year round. In other words, humidity would not be a key factor limiting the formation of secondary aerosols in a humid region. Ammonium was found to play the most critical role in modulating the variations in PM1 mass concentration, followed by nitrate. This could be related to the neutralization of

2

3.4. Ratios of PM1 to PM2.5

To better understand PM pollution in these six regions, we also compared the mass concentration of PM and five major chemical compositions between PM1 and PM2.5 (using PM2.1 as a proxy). Given the simultaneous sampling, we calculated their mass concentration ratios (PM1/PM2.5) and the results are summarized in Table 5. It is seen that PM1 accounted for 66%?75% mass concentration of PM2.5 that were measured in these six regions, which is slightly higher than that in Tianjin (63%) as discovered in Khan et al. (2021). Such a high PM1/PM2.5 ratio implies PM2.5 in these six regions was largely dominated by small size particles due to combustion processes and secondary aerosols rather than natural sources and mechanical processes (Khan et al., 2021). Meanwhile, this also highlights the notorious negative health impacts of PM2.5 since nearly 70% of its composition is from submicron particles.| Region | N | PM | EC | OM | $ {\rm{NO}}_{3}^{-} $ | $ {\rm{SO}}_{4}^{2-} $ | $ {\rm{NH}}_{4}^{+} $ |

| Qinghai | 53 | 0.71±0.10 | 0.84±0.16 | 0.79±0.10 | 0.71±0.12 | 0.80±0.10 | 0.94±0.09 |

| ürümqi | 71 | 0.71±0.11 | 0.78±0.18 | 0.78±0.10 | 0.72±0.14 | 0.72±0.17 | 0.80±0.18 |

| Xi’an | 72 | 0.66±0.08 | 0.79±0.11 | 0.70±0.11 | 0.63±0.12 | 0.67±0.13 | 0.73±0.14 |

| Chengdu | 71 | 0.69±0.07 | 0.79±0.09 | 0.73±0.08 | 0.68±0.09 | 0.66±0.12 | 0.68±0.12 |

| Shanghai | 71 | 0.73±0.06 | 0.83±0.09 | 0.81±0.09 | 0.70±0.10 | 0.76±0.10 | 0.79±0.12 |

| Guangzhou | 70 | 0.75±0.04 | 0.88±0.08 | 0.81±0.06 | 0.70±0.10 | 0.80±0.09 | 0.85±0.13 |

Table5. Same as in Table 2 but for comparison of mean mass concentration ratios of PM and five major chemical compositions between PM1 and PM2.1.

Spatially, PM1 accounted for a larger fraction of PM2.5 mass concentration in the two coastal megacities of Shanghai (0.73) and Guangzhou (0.75), where primary emissions from vehicles and ships are normally more extensive than in the two inland megacities of Xi’an (0.66) and Chengdu (0.69). Such a spatial distribution of PM1/PM2.5 ratio is also in line with previous studies in Chen et al. (2018) as high ratios were mainly observed in Southeastern and Central China while low ratios were found in Western China where natural sources are also important contributions. Moreover, this ratio varied with pollution regimes and humidity. For instance, Qiao et al. (2016) found a relatively high PM1/PM2.5 ratio on clean days whereas an elevated ratio of PM1?2.5/PM2.5 on hazy days. Sun et al. (2020) also revealed that the changes in PM1/PM2.5 ratios as a function of RH were largely different for primary and secondary aerosol species due to distinct aerosol hygroscopicity and phase states.

In regard to the five major chemical compositions, we found that most major PM2.5 constituents in Guangzhou were PM1 given higher ratios of chemical species, except nitrate and ammonium, which had the largest fraction in ürümqi (0.72) and Qinghai (0.94), respectively. This implies PM2.5 pollution in Guangzhou is mainly dominated by submicron fine particle pollution events, followed by Shanghai given the second highest ratio. On the contrary, Xi’an and Chengdu are two cities having relatively low fractions in chemical compositions. This result suggests even more diverse emission sources in these two inland cities, since a larger fraction of chemical compositions in PM2.5 was contributed by coarser particles. Overall, our results indicate that the main sources of PM1 and PM2.5 in the two coastal cities were dominated by combustion processes and secondary aerosols while natural sources and mechanical emissions could contribute significantly in the two inland cities.

Comparisons of OC/EC and

Meteorological factors were shown to play important roles in modulating the variability of PM1 mass loading. Our modeling practices have clearly revealed that ambient PM1 mass concentration was largely regulated by primary emissions (e.g., Qinghai and ürümqi) and secondary aerosol formations (e.g., Xi’an, Shanghai, and Chengdu). Meanwhile, the importance of meteorological factors was found to vary across regions under different pollution regimes. Overall, the results in this study clearly indicate that there is no common driving mechanism for haze events due to diverse sources and influential factors. Due to the data issue, an elemental analysis was not performed in the current study, but this should be included in future field campaigns to more fully investigate the driving factors behind haze events.

Acknowledgements. We are grateful to three anonymous reviewers and editors for their copious and constructive comments and suggestions. This work was financially supported by National Key R&D Plan (Grant No. 2017YFC0210000), National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 41701413), National Key R&D Plan (Grant No. 2017YFC0212703) and Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Grant No. XDB05020401). Meteorological data were acquired from the Meteorological Information Comprehensive Analysis and Process System (air temperature, relative humidity, and wind speed), and ERA-Interim reanalysis (boundary layer height) that was provided by the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts.