芦科堃, 向文良

, 卢倩文

, 卢倩文 西华大学食品与生物工程学院, 四川省食品生物技术重点实验室, 西华大学古法酿造生物技术研究所, 四川 成都 610039

收稿日期:2018-04-23;修回日期:2018-07-12;网络出版日期:2018-08-20

基金项目:国家自然科学基金(31571935);四川省应用基础重点(2018JY0045);成都市一般项目(2016-NY02-00064-NC);西华大学研究生创新基金(YCJJ2017044)

*通信作者:向文良。Tel/Fax:+86-28-87725899;E-mail:biounicom@mail.xhu.edu.cn

摘要:[目的] 分析有机、化肥和野生折耳根表面的附生细菌群落结构和抗生素抗性基因(ARGs),揭示细菌群落结构与ARGs相互关系。[方法] 高通量测定16S rRNA V3-V4可变区序列分析样品表面附生细菌群落结构;PCR和qPCR扩增29种ARGs基因分析样品表面ARGs污染情况;冗余分析(RDA)探讨细菌群落结构与ARGs的相互关系。[结果] 折耳根表面检测到35个属的细菌,其中有机折耳根表面附生细菌多样性低于化肥和野生折耳根(P < 0.05);29种被检的ARGs中,有14种在折耳根中被检出,其中有机折耳根含有全部被检出的ARGs,化肥和野生折耳根则含有部分被检出的ARGs。折耳根表面ARGs污染的多样性和丰度显著受到样品表面的菌群结构影响,其中Lactococcus、Escherichia、Fluviicola、Enterococcus、Sanguibacter和Acidovorax是影响ARGs最主要的菌群。[结论] 有机种植极大地改变了折耳根表面附生细菌的群落结构,增加了ARGs的多样性和丰度,对有机折耳根的食品安全带来了潜在威胁。因此,有必要将ARGs污染监测纳入到有机折耳根的食品安全考核范围内。

关键词:折耳根高通量测序原核微生物多样性抗生素抗性基因定量PCR

Bacterial community structure and antibiotic resistance gene on the surface of Houttuynia cordata Thunb from different planting patterns in Chengdu plain

Kekun Lu, Wenliang Xiang

, Qianwen Lu

, Qianwen Lu Key Laboratory of Food Biotechnology of Sichuan, Institute of Traditional Brewing Technology, College of Food and Bioengineering, Xihua University, Chengdu 610039, Sichuan Province, China

Received 23 April 2018; Revised 12 July 2018; Published online 20 August 2018

*Corresponding author: Wenliang Xiang. Tel/Fax:+86-28-87725899. E-mail:biounicom@mail.xhu.edu.cn

Supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31571935), by the Applied Basic Research Program of Sichuan, China (2018JY0045), by the General Program of Chengdu (2016-NY02-00064-NC) and by the Graduate Student Innovation Fund of Xihua University (YCJJ2017044)

Abstract: [Objective] The aim of this study is to analyze bacterial community and antibiotic resistant genes (ARGs) in organic, fertilized and wild Houttuynia cordata Thunb, and to reveal the relationship between bacterial community and ARGs. [Methods] The bacterial community structure was investigated by high-throughput 16S rRNA V3-V4 variable region sequencing. The qualitative and quantitative analysis of 29 ARGs was determined by PCR and qPCR. The redundancy analysis was used to reveal the relationship between bacterial community and ARGs. [Results] A total of 35 genera of bacteria were detected. The bacterial diversity in organic H. cordata Thunb was lower than that in fertilized and wild H. cordata Thunb. Fourteen ARGs were detected on H. cordata Thunb. All detected ARGs were found in the organic H. cordata Thunb, while only part was found in the fertilized and wild H. cordata Thunb. Redundancy analysis showed ARGs were significantly affected by bacterial diversity and abundance, and Lactococcus, Escherichia, Fluviicola, Enterococcus, Sanguibacter and Acidovorax were main bacteria which affected on the diversity and abundance of ARGs on H. cordata Thunb. [Conclusion] Organic planting affects bacterial community on H. Cordata Thunb, and increases diversity and abundance of ARGs, suggesting a potential food safety risk. Therefore, it is necessary to bring ARGs contamination into the scope of food safety assessment for organic H. cordata Thunb.

Keywords: Houttuynia cordata Thunbhigh throughput sequencingprokaryotic microbial diversityantibiotic resistance genesquantitative PCR

折耳根(Houttuynia cordata Thunb)又名鱼腥草,是一种多年生常见的药食两用草本植物,以鲜食为主,为三白草科折耳根属,多生长在背阴山坡、村边田埂、河畔溪边及湿地草丛中,广泛分布于我国南方各省区,尤以云、贵、川地区居多。研究表明,折耳根含有许多健康成分,如精油、类黄酮、多酚、生物碱、有机酸、脂肪酸、甾醇和微量元素,同时具有多种药理活性,包括利尿、抗菌、抗病毒、抗肿瘤、抗炎、抗氧化、抗糖尿病、抗过敏和抗诱变等作用[1-3]。然而,随着需求增加和不规律采集,野生折耳根资源受到了极大破坏,产量不断下降。为满足社会需求,近几十年来,折耳根的人工种植迅速发展起来。在这些种植中,有机种植被认为是最有发展前景和最安全的种植方式。

抗生素在畜牧业、农业和养殖业的大量使用或滥用造成了农业生态环境微生物群落结构发生改变,含有抗生素抗性基因(ARGs)的微生物菌群明显增加[4]。蔬菜在种植过程中不可避免地会污染这些ARGs携带菌或离体的ARGs,当这些ARGs携带菌或离体的ARGs伴随蔬菜特别是生食蔬菜进入人体肠道后,可能会通过水平转移机制将ARGs转移给其他微生物,甚至是致病菌,从而给疾病治疗带来困难。因此,农业生态ARGs污染加剧对农产品特别是鲜食蔬菜的食品安全造成了潜在威胁[5-8]。

目前,国内外关于ARGs污染的研究主要是针对城市污泥、猪场土壤、垃圾处理场和蔬菜基地等环境中微生物,而对折耳根表面附生细菌以及ARGs污染情况鲜有报道。因此本研究以有机、化肥和野生折耳根为实验对象,高通量测定原核微生物16S rRNA V3-V4可变区,分析折耳根样品表面附生细菌群落结构和多样性;PCR和qPCR对四环素类、氨基糖苷类和β-内酰胺类共29种ARGs进行定性和定量检测,然后通过冗余分析(RDA)揭示附生细菌菌群和ARGs之间的相关性,以期为从ARGs角度评估鲜食折耳根的安全性提供基础数据。

1 材料和方法 1.1 样品采集及预处理 选取成都平原周边9个折耳根生产点作为采样点,包括6个人工种植基地(3个化肥种植和3个有机种植)和3个折耳根野生地。其中,人工种植点自然环境良好,污染较少,一直以来为农业耕地,过去以种植水稻为主,目前已连续种植折耳根5年以上;3个有机折耳根生产基地严格按照国家有机食品标准GB/T 19630.1-2011进行生产,在折耳根种植过程中以畜禽粪便经堆积发酵后为主要肥料,禁止使用化肥、农药、生长调节剂等。化肥种植则以商用化肥作为肥料,野生折耳根采集于自然生长地。各蔬菜基地主要以地下水为灌溉水。采样时间为2017年3月。采用5点混合采样法,每个采样点采集3种生产方式的折耳根各3份重复样品,放入装有冰盒的采样箱运回实验室,–80 ℃保存,备用。

1.2 原核微生物群落分析 无菌水冲洗折耳根样品后,根据Bokai Zhu等[9]的方法分离折耳根表面的微生物,FastDNA? Spin Kit for Soil (MP Biomedicals,美国)进行总DNA提取。DNA提取完毕后,用微量核酸蛋白分析仪(NanoDrop Technologies Inc,美国)测定DNA浓度和纯度,于–80 ℃保存。

高通量测序检测折耳根中表面附生细菌的群落结构并分析多样性。引物341F (5′-AGAGTTTG ATCCTGGCTCAG-3′)和806R (5′-TTACCGCGGCT GCTGGCAC-3′)扩增16S rRNA V3-V4可变区[10],Illuminate Hiaeq 2500 (上海美吉生物医药有限公司)平台完成测序。

使用QIIME[11]软件对测序数据进行过滤,通过flash[12]软件将有overlap的一对reads进行拼接。用UClust[13]软件对序列进行聚类,将97%相似性的序列聚类成为OTUs (operational taxonomic units),RDP classifier[14]对序列进行物种注释。统计每个样品在各分类水平上的构成,利用OTUs的数值及比对注释种类到属水平上计算各个采样点的Chao1、Shannon和PD指数分析比较原核微生物群落多样性。

1.3 ARGs的PCR和qPCR分析 PCR检测折耳根中的ARGs,扩增引物序列见表 1。在此基础上,荧光定量PCR (Analytikjena,德国)测定折耳根样品中的总基因拷贝数(16S rRNA)、3类抗生素(氨基糖苷类、四环素类和β-内酰胺类抗生素)抗性基因的浓度。并采用标准质粒外标法对样品的丰度进行绝对定量[6]。所制备的标准质粒浓度为1.75×1010–1.83×1011 copies/L。选取5个点,通过预实验选取标准品的10–2–10–8稀释液用于制备标准曲线。qPCR反应体系为20 μL,10 μL的SybrGreen qPCR Master Mix (TaKaRa,日本),0.5 μL的DNA模板,0.4 μL的10 μmol/L上下游引物和9.1 μL灭菌超纯水。扩增效率为96.27%–118.17%,R2值为0.9915–0.9996。每个样品做3次重复,每次设置阴性对照实验。

表 1. 检测的基因种类及其参考文献 Table 1. Detected gene types and related references

| Antibiotics | Genes | Ref. |

| Aminoglycoside | strA、strB、aadA | [15] |

| Tetracycline | tetA、tetE | [16] |

| tetB、tetC、tetD、tetG、tetL、tetO、tetQ、tetS、tetW、tetX | [17] | |

| tetH、tetJ、tetK、tetY、tetZ、tet30、tetBP | [18] | |

| tetM | [19] | |

| tetT、OtrA | [20] | |

| β-lactamase | Bla-tem、Bla-oxa-1 | [21] |

| Bla、BlaZ | [22] | |

| 16S rRNA | [23] |

表选项

1.4 统计分析 不同样品间显著性平均值差异采用SPSS20.0进行t-Test检验,P < 0.05为显著水平。Excel 2003和Heatmap用于细菌群落统计热点图分析;Canoco 4.5分析软件和Canodraw 4.5分析ARGs和微生物群落相互关系。

2 结果和分析 2.1 细菌群落多样性 9个样品获得总共357282个高质量序列(表 2),每个样品的序列数为34093至46029。这些序列按97%相似性划分为1245个OTU。野生、化肥和有机折耳根样品的平均OTU数分别为201、136和81,9组样品文库覆盖率均在95%以上,能够反映样品中真实存在的细菌种类和结构。

表 2. 折耳根样品的Alpha指数统计表 Table 2. Alpha indices statistics

| Sample | Reads | OTUs | Chao1 | Shannon | PD | Good's coverage/% |

| OPH | 37419 | 85 | 84.21 | 2.45 | 4.56 | 97.01 |

| OJH | 36927 | 80 | 88.07 | 1.99 | 5.02 | 95.55 |

| OSH | 34093 | 79 | 85.50 | 2.03 | 4.73 | 95.37 |

| CPH | 42170 | 135 | 144.71 | 3.65 | 7.18 | 96.74 |

| CJH | 44021 | 128 | 133.83 | 3.67 | 6.47 | 95.38 |

| CSH | 35897 | 146 | 152.57 | 2.47 | 7.94 | 95.82 |

| WPH | 42098 | 204 | 207.00 | 4.77 | 10.15 | 96.64 |

| WJH | 46029 | 200 | 213.93 | 4.94 | 10.67 | 95.99 |

| WSH | 38628 | 199 | 273.37 | 4.40 | 10.17 | 97.82 |

| O, C and W respectively indicate organic planting, fertilizer planting and wild planting; P, S and J respectively indicate the planting sites of Pengzhou, Shifang and Jintang; H indicates H. cordata Thunb. | ||||||

表选项

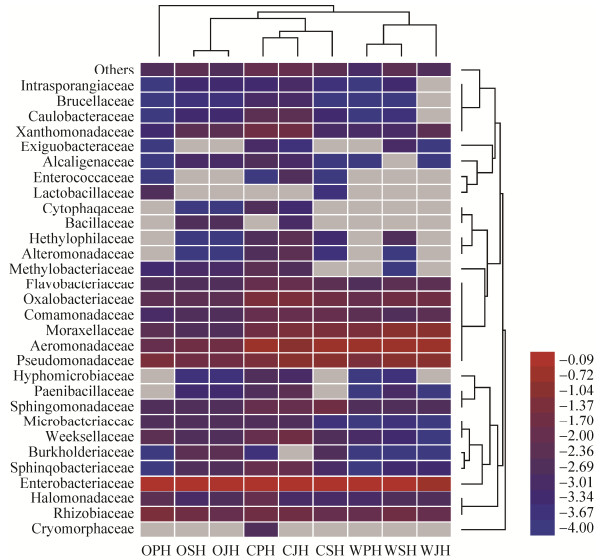

测序得到的OTU数经分析主要为原核微生物的8个门,包括变形菌门(Proteobacteria,92.0%–99.5%)、拟杆菌门(Bacteroidetes,0%–0.1%)和放线菌门(Actinobacteria,0.005%–0.015%)等。9个折耳根样品中的细菌分属于35个属的微生物(图 1),其中优菌属依次为假单胞菌属(Pseudomonas,0.67%–12.14%)、泛菌属(Pantoea,1.39%–20.84%)、不动杆菌属(Acinetobacter,2.64%–9.44%)、农杆菌属(Agrobacterium)、草螺属(Herbaspirillum)、嗜菌属(Stenotrophomonas)、金黄杆菌属(Chyseobacterium)、黄杆菌属(Flavobacterium)和盐单胞菌属(Halomonas),但他们在不同种植折耳根中所占比例差异较大,如:假单胞菌属在有机、化肥和野生折耳根中的比例分别为10.00%–12.14%、0.67%–0.79%和7.03%–8.96%;泛菌属在有机、化肥和野生折耳根中的比例则分别为7.00%–20.84%、1.39%–3.13%和6.47%–9.20%;而不动杆菌属在有机、化肥和野生折耳根中的比例则分别为6.00%–9.44%、2.64%–5.01%和3.90%–9.18%。

基于每个样品中物种种类和丰度,对菌群进行分类地位聚类和样本聚类(图 1),结果表明:有机种植的折耳根表面的细菌群落结构与化肥种植的相近,与野生折耳根相差较大。其中Pseudomonas、Pantoea、Acinetobacter和Agrobacterium在所有折耳根样品中的丰度均显著高于其他菌属。基于细菌种类和丰度,3个有机的折耳根样品和3个化肥的折耳根样品聚为一簇,野生折耳根样品单独为一簇,表明有机和化肥种植的折耳根相比于野生折耳根在细菌群结构组成上发生了明显变化。总体而言,有机折耳根表面附生细菌多样性小于化肥和野生折耳根。

|

| 图 1 折耳根表面附生细菌菌群聚类 Figure 1 The cluster analysis of the bacterial community in samples |

| 图选项 |

2.2 ARGs的种类和丰度 根据PCR和qPCR分析结果,折耳根样品中总ARGs的绝对拷贝数和相对拷贝数达到4.86×102–2.02×106和1.83×10–4–3.93×10–2(图 2),其中有机折耳根样品的总ARGs的绝对拷贝数和相对拷贝数均高于化肥和野生折耳根样品。

|

| 图 2 总ARGs的绝对拷贝数和相对拷贝数 Figure 2 The absolute and relative abundance of total ARGs.Error bars represent discreteness of multiple experiments |

| 图选项 |

折耳根样品中检出了9种四环素、3种氨基糖苷和2种β-内酰胺酶基因(图 3)。有机折耳根样品中检出的四环素耐药基因包括6个外排泵基因(tetA、tetB、tetC、tetD、tetE和tetG)、1个核糖体保护蛋白基因(tetM)和1个酶修饰基因(tetX)的四环素抗性基因,而施用化肥的折耳根样品中仅发现tetE和tetX四环素耐药基因,野生折耳根样品中没有四环素抗性基因;9个样品中每种种植方式或者每处地区的样品中都检测到3种编码氨基糖苷类抗性基因,包括核苷酸转移酶基因(aadA)和磷酸转移酶基因(strA和strB);β-内酰胺酶(Bla-tem和Bla-oxa-1)耐药基因仅在有机和化肥折耳根样品中发现,野生样品中没有检出。qPCR结果表明,有机折耳根样品中tetA、tetC和tetE的绝对拷贝数高达2.04×104–2.09×105 copies/g、1.14×104–3.10×105 copies/g和3.08×104–1.92×106 copies/g,相对拷贝数为9.03×10–4–3.35×10–2、9.34×10–4–4.97×10–2和4.94×10–3–8.50×10–2。aadA的绝对拷贝数为3.71×104–4.92×105 copies/g,相对拷贝数为2.46×10–3–7.88×10–2。上述结果表明,有机种植和施用化肥的折耳根比野生折耳根污染了更重的ARGs。

|

| 图 3 折耳根中ARGs的绝对丰度和相对丰度 Figure 3 The absolute abundance (A) and relative abundance (B) of ARGs in HCT |

| 图选项 |

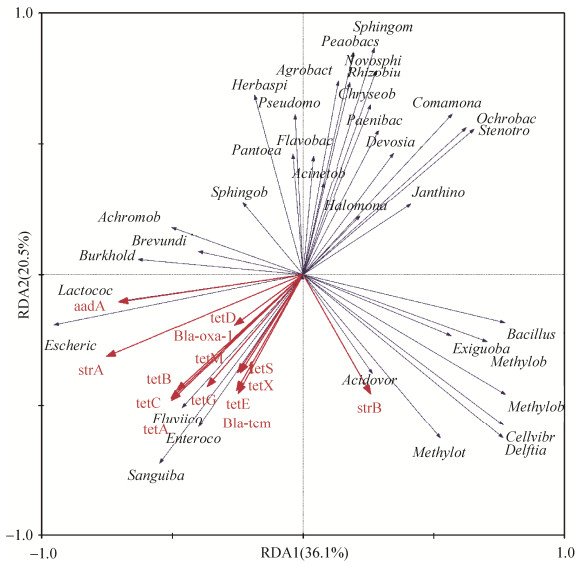

2.3 细菌菌群与ARGs的相关性 为了明确细菌群落与ARGs的关系,对9个折耳根样品中属水平的细菌种类与ARGs相对丰度进行RDA分析(图 4)。RDA结果表明,第一和第二排序轴分别对应36.1%和20.5%的抗性基因相对丰度与菌群结构的关系。Lactococcus、Escherichia、Burkholderia、Brevundimonas和Achromobacter菌群丰度与aadA显著正相关,Fluviicola、Enterococcus和Sanguibacter菌属与tetA、tetB、tetC、tetD、tetE、tetG、tetM、tetS、tetX、strA、Bla-oxa-1和Bla-tem呈显著正相关,Acidovorax、Methylotenera和Delftia等与strB显著正相关。而多数检出的属菌群丰度如Janthinobacterium、Stenotrophomonas、Ochrobactrum和Comamonas等与所有检出的ARGs均显著负相关。

|

| 图 4 原核微生物群落与ARGs的相关性 Figure 4 The relationship between bacterial community and ARGs |

| 图选项 |

3 讨论 2006年,ARGs作为一种新型的环境面源污染物由美国****Pruden[24]首次提出,由于其在环境介质中的持久残留以及在不同宿主间的水平转移往往比抗生素本身的危害更大,因此其对食品安全和公共健康构成的威胁,已逐渐成为植物学、土壤学、环境科学和食品科学等领域的研究热点[25-28]。长期以来,蔬菜生产过程中一直忽视ARGs的影响,特别是有机蔬菜。动物粪便是ARGs的潜在基因库,动物粪便在有机农业种植中的使用会显著增加蔬菜表面ARGs的丰度[29],Marti等的研究指出仅在施粪肥蔬菜上检出了不属于土壤中的ARGs[30],表明粪肥能增加ARGs的丰度和多样性。在调查的29种ARGs中,有机种植折耳根样品比施用化肥和野生折耳根样品检出更多的ARGs,同时总ARGs的相对拷贝数达到非有机种植折耳根的2000倍以上,表明有机种植增加了折耳根中ARGs的污染程度。目前关于蔬菜和水果表面ARGs的污染情况的研究指出,施用畜禽粪便会增加蔬菜中抗生素抗性菌和ARGs的检出频率[28],有些ARGs只在使用有机粪肥的蔬菜附生菌中检出[31]。最近研究指出植物叶面和根部附生原核微生物在很大程度上有重叠现象,表明植物中原核微生物可能来源于土壤[32],原核微生物可以在土壤和植物叶部之间互相迁移[33]。例如,土壤微生物可以影响葡萄藤中的微生物[34],并且可作为多种根际原核微生物的起始物种[35]。原核微生物在土壤和植物中的来回迁移可能是增加蔬菜中ARGs丰度的最重要的原因之一。此外,通过气溶胶传播的土壤微生物也是植物叶面微生物的主要来源之一,进一步增加植物叶际ARGs的丰度[10]。

微生物菌群的改变会影响ARGs的种类和丰度,但是目前关于蔬菜中微生物菌群改变导致ARGs变化的研究较少。高通量测序表明有机和化肥折耳根表面原核微生物菌群多样性相比于野生折耳根发生了显著改变(P < 0.05),这与之前报道的长期施用鸡粪便降低了莴笋叶片细菌群落的多样性的结果一致[36]。微生物菌群结构与ARGs之间的RDA分析表明,Lactococcus与aadA等显著正相关,Methylotenera和Bacillus与strB正相关,而这三种菌属在有机折耳根中的比例都高于野生折耳根样品。由此可以推测,蔬菜中微生物菌群结构的改变会影响ARGs的分布。

本研究一方面利用高通量测序分析折耳根表面原核微生物的多样性,较全面地揭示了折耳根中原核微生物的结构组成,但是由于测序深度有限,未对原核微生物在种上的分布进行解读,在后续实验中应该更深入地研究原核微生物的多样性。另一方面通过PCR和qPCR对有限的ARGs进行定性和定量分析,为了更全面地了解蔬菜中ARGs的污染情况,在后续研究中可以利用高通量定量PCR技术对ARGs的污染情况提供更广泛的信息。此外,原核微生物与ARGs的相关性还需建立在高通量测序手段上进行精准的预测。

4 结论 人工种植影响折耳根表面原核微生物群落结构,增加ARGs的种类和丰度,有机种植对此影响表现最显著。因此有必要把ARGs污染作为有机蔬菜的安全指标之一。

References

| [1] | Oh SY. An effective quality control of pharmacologically active volatiles of Houttuynia cordata Thunb by fast gas chromatography-surface acoustic wave sensor. Molecules, 2015, 20(6): 10298-10312. DOI:10.3390/molecules200610298 |

| [2] | Sekita Y, Murakami K, Yumoto H, Mizuguchi H, Amoh T, Ogino S, Matsuo T, Miyake Y, Fukui H, Kashiwada Y. Anti-bacterial and anti-inflammatory effects of ethanol extract from Houttuynia cordata poultice. Bioscience, Biotechnology, and Biochemistry, 2016, 80(6): 1205-1213. DOI:10.1080/09168451.2016.1151339 |

| [3] | Li J, Zhao FT. Anti-inflammatory functions of Houttuynia cordata Thunb. and its compounds:a perspective on its potential role in rheumatoid arthritis. Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine, 2015, 10(1): 3-6. DOI:10.3892/etm.2015.2467 |

| [4] | Huang CH, Renew JE, Smeby KL, Pinkston K, Sedlak DL. Assessment of potential antibiotic contaminants in water and preliminary occurrence analysis. Journal of Contemporary Water Research and Education, 2001, 120(1): 30-40. |

| [5] | Abriouel H, Omar NB, Molinos AC, López RL, Grande MJ, Martínez-Viedma P, Ortega E, Ca?amero MM, Galvez A. Comparative analysis of genetic diversity and incidence of virulence factors and antibiotic resistance among enterococcal populations from raw fruit and vegetable foods, water and soil, and clinical samples. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 2008, 123(1/2): 38-49. |

| [6] | Boehme S, Werner G, Klare I, Reissbrot R, Witte W. Occurrence of antibiotic-resistant enterobacteria in agricultural foodstuffs. Molecular Nutrition and Food Research, 2004, 48(7): 522-531. DOI:10.1002/(ISSN)1613-4133 |

| [7] | Durso LM, Miller DN, Wienhold BJ. Distribution and quantification of antibiotic resistant genes and bacteria across agricultural and non-agricultural metagenomes. PLoS One, 2012, 7(11): e48325. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0048325 |

| [8] | Rodríguez C, Lang L, Wang A, Altendorf K, García F, Lipskí A. Lettuce for human consumption collected in Costa Rica contains complex communities of culturable oxytetracycline- and gentamicin-resistant bacteria. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2006, 72(9): 5870-5876. DOI:10.1128/AEM.00963-06 |

| [9] | Zhu BK, Chen QL, Chen SC, Zhu YG. Does organically produced lettuce harbor higher abundance of antibiotic resistance genes than conventionally produced?. Environment International, 2017, 98: 152-159. DOI:10.1016/j.envint.2016.11.001 |

| [10] | Tang JY, Bu YQ, Zhang XX, Huang KL, He XW, Ye L, Shan ZJ, Ren HQ. Metagenomic analysis of bacterial community composition and antibiotic resistance genes in a wastewater treatment plant and its receiving surface water. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety, 2016, 132: 260-269. DOI:10.1016/j.ecoenv.2016.06.016 |

| [11] | Caporaso JG, Kuczynski J, Stombaugh J, Bittinger K, Bushman FD, Costello EK, Fierer N, Pe?a AG, Goodrich JK, Gordon JI, Huttley GA, Kelley ST, Knights D, Koenig JE, Ley RE, Lozupone CA, McDonald D, Muegge BD, Pirrung M, Reeder J, Sevinsky JR, Turnbaugh PJ, Walters WA, Widmann J, Yatsunenko T, Zaneveld J, Knight R. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nature Methods, 2010, 7(5): 335-336. DOI:10.1038/nmeth.f.303 |

| [12] | Mago? T, Salzberg SL. FLASH:fast length adjustment of short reads to improve genome assemblies. Bioinformatics, 2011, 27(21): 2957-2963. DOI:10.1093/bioinformatics/btr507 |

| [13] | Edgar RC. Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST. Bioinformatics, 2010, 26(19): 2460-2461. DOI:10.1093/bioinformatics/btq461 |

| [14] | Wang Q, Garrity MG, Tiedje MJ, Cole RJ. Na ve Bayesian classifier for rapid assignment of rRNA sequences into the new bacterial taxonomy. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2007, 73(16): 5261-5267. DOI:10.1128/AEM.00062-07 |

| [15] | Mao DQ, Yu S, Rysz M, Luo YX, Yang FX, Li FX, Hou J, Mu QH, Alvarez PJJ. Prevalence and proliferation of antibiotic resistance genes in two municipal wastewater treatment plants. Water Research, 2015, 85: 458-466. DOI:10.1016/j.watres.2015.09.010 |

| [16] | Ouoba LII, Lei V, Jensen LB. Resistance of potential probiotic lactic acid bacteria and bifidobacteria of African and European origin to antimicrobials:determination and transferability of the resistance genes to other bacteria. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 2008, 121(2): 217-224. DOI:10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2007.11.018 |

| [17] | Zhang J, Yang XH, Ge F, Wang N, Jiao SJ, Ye BP. Effects of long-term application of pig manure containing residual tetracycline on the formation of drug-resistant bacteria and resistance genes. Environmental Science, 2014, 35(6): 2374-2380. (in Chinese) 张俊, 杨晓洪, 葛峰, 王娜, 焦少俊, 叶波平. 长期施用四环素残留猪粪对土壤中耐药菌及抗性基因形成的影响. 环境科学, 2014, 35(6): 2374-2380. |

| [18] | Jia SY, He XW, Bu YQ, Shi P, Miao Y, Zhou HP, Shan ZJ, Zhang XX. Environmental fate of tetracycline resistance genes originating from swine feedlots in river water. Journal of Environmental Science and Health Part B-Pesticides, Food Contaminants, and Agricultural Wastes, 2014, 49(8): 624-631. |

| [19] | Jiang L, Hu XL, Xu T, Zhang HC, Sheng D, Yin DQ. Prevalence of antibiotic resistance genes and their relationship with antibiotics in the Huangpu River and the drinking water sources, Shanghai, China. Science of the Total Environment, 2013, 458-460: 267-272. DOI:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.04.038 |

| [20] | Zhang AY, Wang HN, Tian GB, Zhang Y, Yang X, Xia QQ, Tang JN, Zou LK. Phenotypic and genotypic characterisation of antimicrobial resistance in faecal bacteria from 30 Giant pandas. International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents, 2009, 33(5): 456-460. DOI:10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2008.10.030 |

| [21] | Aminov RI, Garrigues-Jeanjean N, Mackie RI. Molecular ecology of tetracycline resistance:development and validation of primers for detection of tetracycline resistance genes encoding ribosomal protection proteins. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2001, 67(1): 22-32. DOI:10.1128/AEM.67.1.22-32.2001 |

| [22] | Zhang JY, Chen MX, Sui QW, Wang R, Tong J, Wei YS. Fate of antibiotic resistance genes and its drivers during anaerobic co-digestion of food waste and sewage sludge based on microwave pretreatment. Bioresource Technology, 2016, 217: 28-36. DOI:10.1016/j.biortech.2016.02.140 |

| [23] | Casado Mu?oz MdelC, Benomar N, Lavilla LL, Gálvez A, Abriouel H. Antibiotic resistance of Lactobacillus pentosus and Leuconostoc pseudomesenteroides isolated from naturally-fermented Alore a table olives throughout fermentation process. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 2014, 172: 110-118. DOI:10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2013.11.025 |

| [24] | Pruden A, Pei RT, Storteboom H, Carlson KH. Antibiotic resistance genes as emerging contaminants:studies in northern Colorado. Environmental Science & Technology, 2006, 40(23): 7445-7450. |

| [25] | Tian Z, Zhang Y, Yu B, Yang M. Changes of resistome, mobilome and potential hosts of antibiotic resistance genes during the transformation of anaerobic digestion from mesophilic to thermophilic. Water Research, 2016, 98: 261-269. DOI:10.1016/j.watres.2016.04.031 |

| [26] | Martínez JL. Antibiotics and antibiotic resistance genes in natural environments. Science, 2008, 321(5887): 365-367. DOI:10.1126/science.1159483 |

| [27] | van Hoek AHAM, Mevius D, Guerra B, Mullany P, Roberts AP, Aarts HJM. Acquired antibiotic resistance genes:an overview. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2011, 2: 203. |

| [28] | Wang FH, Qiao M, Chen Z, Su JQ, Zhu YG. Antibiotic resistance genes in manure-amended soil and vegetables at harvest. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 2015, 299: 215-221. DOI:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2015.05.028 |

| [29] | Chen QL, An XL, Li H, Su JQ, Ma YB, Zhu YG. Long-term field application of sewage sludge increases the abundance of antibiotic resistance genes in soil. Environment International, 2016, 92-93: 1-10. DOI:10.1016/j.envint.2016.03.026 |

| [30] | Marti R, Scott A, Tien YC, Murray R, Sabourin L, Zhang Y, Topp E. Impact of manure fertilization on the abundance of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and frequency of detection of antibiotic resistance genes in soil and on vegetables at harvest. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2013, 79(18): 5701-5709. DOI:10.1128/AEM.01682-13 |

| [31] | Ross J, Topp E. Abundance of antibiotic resistance genes in bacteriophage following soil fertilization with dairy manure or municipal biosolids, and evidence for potential transduction. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2015, 81(22): 7905-7913. DOI:10.1128/AEM.02363-15 |

| [32] | Bai Y, Müller DB, Srinivas G, Garrido-Oter R, Potthoff E, Rott M, Dombrowski N, Münch PC, Spaepen S, Remus-Emsermann M, Hüttel B, McHardy AC, Vorholt JA, Schulze-Lefert P. Functional overlap of the Arabidopsis leaf and root microbiota. Nature, 2015, 528(7582): 364-369. DOI:10.1038/nature16192 |

| [33] | Ruiz-Pérez CA, Restrepo S, Zambrano MM. Microbial and functional diversity within the phyllosphere of Espeletia species in an andean high-mountain ecosystem. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2016, 82(6): 1807-1817. DOI:10.1128/AEM.02781-15 |

| [34] | Zarraonaindia I, Owens SM, Weisenhorn P, West K, Hampton-Marcell J, Lax S, Bokulich NA, Mills DA, Martin G, Taghavi S, van der Lelie D, Gilbert JA. The soil microbiome influences grapevine-associated microbiota. mBio, 2015, 6(2): e02527-14. |

| [35] | Bulgarelli D, Rott M, Schlaeppi K, Ver Loren van Themaat E, Ahmadinejad N, Assenza F, Rauf P, Huettel B, Reinhardt R, Schmelzer E, Peplies J, Gloeckner FO, Amann R, Eickhorst T, Schulze-Lefert P. Revealing structure and assembly cues for Arabidopsis root-inhabiting bacterial microbiota. Nature, 2012, 488(7409): 91-95. DOI:10.1038/nature11336 |

| [36] | Duan ML, Li HC, Gu J, Tuo XX, Sun W, Qian X, Wang XJ. Effects of biochar on reducing the abundance of oxytetracycline, antibiotic resistance genes, and human pathogenic bacteria in soil and lettuce. Environmental Pollution, 2017, 224: 787-795. DOI:10.1016/j.envpol.2017.01.021 |