孙雅如, 李伟程, 余中节, 王旭, 李敏, 王佼, 张和平, 钟智

内蒙古农业大学乳品生物技术与工程教育部重点实验室, 农业农村部奶制品加工重点实验室, 内蒙古 呼和浩特 010018

收稿日期:2018-02-12;修回日期:2018-06-19;网络出版日期:2018-08-20

基金项目:国家自然科学基金(31601451,31622043)

*通信作者:钟智。Tel/Fax:+86-471-4301591;E-mail:imu150zhongzhi@163.com

摘要:[目的] 研究15株分离自自然发酵食品的粪肠球菌(Enterococcus faecalis)和1株粪肠球菌模式株对15种(1种β-内酰胺类和14种非β-内酰胺类)抗生素的耐药性,并通过菌株耐药表型与基因型的关联分析找到粪肠球菌潜在的耐药基因。[方法] 利用微量肉汤稀释法检测试验菌株对15种抗生素的耐药性,运用Scoary软件进行表型与基因型的关联分析。[结果] 16株粪肠球菌对卡那霉素、万古霉素、利奈唑胺和红霉素100%敏感;对其余11种抗生素均表现出不同程度的耐药,其中对克林霉素为100%耐药。基因组关联分析发现了9个功能基因与5种抗生素(氯霉素、环丙沙星、甲氧苄啶、新霉素和四环素)存在显著相关关系,其中基因FAM000296和FAM005768与氯霉素、甲氧苄啶和环丙沙星的耐药性有关。进一步分析发现基因FAM000296和FAM005768同被注释为SecG,但基因FAM005768与基因FAM000296相比在3'端丢失了21个碱基。[结论] 分离自自然发酵食品的粪肠球菌对多种抗生素具有耐药性,其基因组中携带有潜在的耐药基因。因此,对分离自自然发酵食品的粪肠球菌需要进行全面的安全性评估后方可考虑应用。

关键词:粪肠球菌抗生素耐药性关联分析发酵食品

Genome-wide association study on the antibiotic resistance of Enterococcus faecalis isolated from natural fermented food

Yaru Sun, Weicheng Li, Zhongjie Yu, Xu Wang, Min Li, Jiao Wang, Heping Zhang, Zhi Zhong

Key Laboratory of Dairy Biotechnology and Engineering, Ministry of Education; Key Laboratory of Dairy Products Processing, Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs, Inner Mongolia Agricultural University, Hohhot 010018, Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, China

Received 12 February 2018; Revised 19 June 2018; Published online 20 August 2018

*Corresponding author: Zhi Zhong, Tel/Fax: +86-471-4301591; E-mail: imu150zhongzhi@163.com

Supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31601451, 31622043)

Abstract: [Objective] To find out the antibiotic resistance of 15 (1 β-lactam and 14 non-β-lactams) antibiotics and potential antibiotic resistance genes of Enterococcus faecalis, isolated from natural fermented food. [Methods] The antibiotic resistance of Enterococcus faecalis was detected with 15 antibiotics by micro broth dilution method. Then the genome-wide association study was applied to find the potential antibiotic resistance genes of Enterococcus faecalis by Scoary. [Results] This study showed that the 16 strains of Enterococcus faecalis were 100% sensitive to kanamycin, vancomycin, linezolid and erythromycin, but 100% resistant to clindamycin. In addition, the different degrees of antibiotic resistance to other antibiotics were showed in Enterococcus faecalis. The genome-wide association study found 9 potential antibiotic resistance genes, which were significantly correlated with 5 antibiotics (chloramphenicol, ciprofloxacin, trimethoprim, neomycin and tetracycline). Genes, including FAM000296 and FAM005768, were related to the resistance of chloramphenicol, trimethoprim and ciprofloxacin. FAM000296 and FAM005768 were both annotated as SecG, while compared to FAM000296, FAM005768 lost 21 bases at the 3 end. [Conclusion] Enterococcus faecalis isolated from natural fermented products is resistant to many antibiotics and carries potentially antibiotic resistant genes in its genome. Therefore, a comprehensive safety of Enterococcus faecalis should be assessed before application.

Keywords: Enterococcus faecalisantibiotics resistancegenome-wide association studyfermented food

粪肠球菌(E. faecalis)是肠球菌属的模式种,也是目前研究较多的肠球菌之一,粪肠球菌作为典型的乳酸菌,在食品领域、饲料领域和微生物制剂等相关领域应用十分广泛[1]。尤其在食品行业,常被用于制作奶酪等乳制品,是良好的乳酸菌发酵剂[2]。

粪肠球菌有着较长的安全使用历史,但近年来,粪肠球菌逐渐成为医院常见的病原菌之一,能导致人和动物多个脏器的感染[3]。如果粪肠球菌一旦具有了耐药性或者携带耐药基因,就会给临床治疗带来极大困难,同时如果食品应用中的粪肠球菌携带了耐药基因,就可能随着人们的饮食而进入人体胃肠道,通过水平转移进而传递给其它肠道菌株,甚至是有害菌,最终导致有害菌产生耐药性[4]。

鉴于粪肠球菌的实际应用价值与潜在风险,对其耐药性的研究十分重要。以往对粪肠球菌耐药性的研究主要集中于肠道分离株和致病株。近年来,随着人们对食品安全重视程度的不断加深,对食品中分离获得的粪肠球菌的耐药性研究也越来越多,但对其耐药性和相关基因的关联分析的报道还相对较少。

本实验团队前期已经对15株分离自自然发酵食品中的粪肠球菌进行了全基因组测序。本研究在此基础上全面研究发酵食品中分离获得的粪肠球菌对15种抗生素的耐药性,进一步分析粪肠球菌耐药表型与基因型之间的关联性,为评价发酵食品中粪肠球菌的安全性提供一定的数据参考,同时筛选出一些耐药性低、安全性好的粪肠球菌,为其在食品领域的应用奠定一定的基础。

1 材料和方法 1.1 菌株来源 试验所用16株粪肠球菌(15株自然发酵食品分离株、1株粪肠球菌模式株),均由内蒙古农业大学乳品生物技术与工程教育重点实验室提供。所用菌株及来源如表 1所示。菌株使用M17培养基,37 ℃有氧培养24 h,传至三代备用。

表 1. 粪肠球菌菌株信息 Table 1. List of the Enterococcus faecalis strains analyzed in this study

| Strains | NCBI accession number | Separated from | Origin |

| ATCC 19433T | ASDA00000000.1 | Laboratory purchase | Reference strain |

| DM7-2 | MSQG00000000 | Baotou in Inner Mongolia | Cheese |

| ELS8-4 | MSQH00000000 | Russia Aginsk town | Natural fermented milk |

| HS5152 | MSQI00000000 | Hohhot in Inner Mongolia | Natural fermented porridge |

| HS5302 | MSQJ00000000 | Hohhot in Inner Mongolia | Natural fermented porridge |

| MGA44-7 | MSQK00000000 | Province of Kent, Mongolia | Natural fermented milk |

| NM15-4 | MSQL00000000 | Hulun Buir in Inner Mongolia | Natural fermented milk |

| NM31-3 | MSQM00000000 | Hulun Buir in Inner Mongolia | Natural fermented milk |

| QH-29-4 | MSQN00000000 | Haibei state in Qinghai | Natural fermented yak milk |

| QH9-5 | MSQO00000000 | Haina state in Qinghai | Natural fermented yak milk |

| WZ21-1 | MSQP00000000 | Bayinnaoer in Inner Mongolia | Natural fermented goat milk |

| WZ34-2 | MSQQ00000000 | Bayinnaoer in Inner Mongolia | Natural fermented camel milk |

| XJ76305 | MSQR00000000 | Yili in Xinjiang | Natural fermented milk |

| XM26-4 | MSQS00000000 | Xilin Gol in Inner Mongolia | Koumiss |

| YM11-6 | MSQT00000000 | Erdos in Inner Mongolia | Natural fermented goat milk |

| YM39-2 | MSQU00000000 | Erdos in Inner Mongolia | Natural fermented goat milk |

表选项

1.2 粪肠球菌最小抑菌浓度的测定 粪肠球菌耐药性的测定,即粪肠球菌对不同抗生素最小抑菌浓度(minimum inhibitory concentration,MIC)的测定,MIC值定量反映粪肠球菌的耐药性。本试验采取微量肉汤稀释法对粪肠球菌的耐药性进行测定[5]。

1.2.1 抗生素制备: 粪肠球菌耐药性测定所用的抗生素浓度及其测定范围参考文献[6]。选购的抗生素为保证其效力,需根据厂家提供的效价换算后称取抗生素质量。配制的抗生素需通过滤菌的方式进行灭菌,–80 ℃贮藏。MIC测定时,抗生素浓度以2倍稀释递增。

1.2.2 菌液的制备: 取活化至三代的粪肠球菌菌液划线,挑取单菌落于5 mL生理盐水中至OD625为0.16–0.20,稀释500倍后,置于4 ℃备用。

1.2.3 菌液与抗生素溶液的混合: 粪肠球菌菌液与抗生素溶液的混和添加量,分为水溶性和水不溶性两种[5-7]。混合后粪肠球菌活菌数共稀释1000倍(活菌数约为3×105 CFU/mL)。

MIC测定中需要设置对照组,即加粪肠球菌不加抗生素的阳性对照和不加粪肠球菌加不同浓度抗生素的阴性对照。每组2个平行。

1.2.4 耐药性评价: 通过得到的MIC值,对粪肠球菌进行耐药性评价。当MIC小于或等于临界值时为敏感(susceptible),当MIC大于临界值时为抗性(resistant)。具体评价参照相关标准EFSA,2012[8],CLSI,2012[6],EUC,2002[9]进行。

1.2.5 耐药率的获取: 针对单个抗生素,表现为耐药的菌株数量与总菌株数量的百分比即为菌株对该抗生素的耐药率。

1.3 全基因组关联分析 本研究所用的菌株前期已进行全基因组测序[1],NCBI登录号如表 1所示。通过Scoary (https://github.com/AdmiralenOla/Scoary)[10]软件进行耐药表型与基因型的关联分析。为保证结果的准确性,Scoary软件将对结果进行多次测试校正,当naive P-value、empirical P-value和Benjamini-Hochberg-corrected P-value均小于0.05时,则认为关联结果显著。

将上述关联到的基因分别与Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG, E < 1e-5)[11]数据库、Cluster of Orthologous Groups of proteins (COG, E < 1e-5)[12]数据库和Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database (CARD, E < 1e-5)[13]数据库进行比对,注释基因信息。

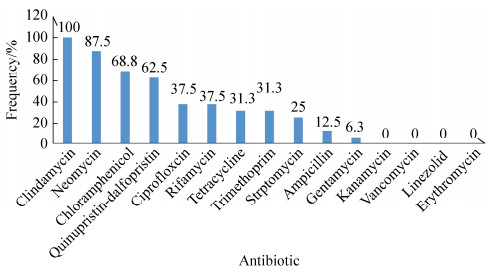

2 结果和分析 2.1 粪肠球菌耐药性结果 16株粪肠球菌对15种抗生素的最低抑菌浓度值如表 2所示,耐药率如图 1所示。结果显示16株粪肠球菌对卡那霉素、万古霉素、利奈唑胺和红霉素不具有耐药性,为100%敏感,而对其余11种抗生素具有不同程度的耐药性。其中所有试验菌株对克林霉素的最低抑菌浓度值均大于16 μg/mL,耐药率为100%。对新霉素、奎奴普丁-达夫普汀和氯霉素的耐药率也很高,分别为87.5%、62.5%和68.8%。此外,试验菌株对氨苄西林和庆大霉素的耐药率较低,分别为12.5%和6.3%。

|

| 图 1 16株粪肠球菌对不同抗生素的耐药率 Figure 1 Antibiotic resistance rates of 16 strains of Enterococcus faecalis. |

| 图选项 |

表 2. 粪肠球菌对15种抗生素的MIC分布结果 Table 2. The MIC distribution results of Enterococcus faecalis to 15 antibiotics

| Strains | CLI | NEO | CHL | QUI | CIP | RIF | TET | TRI | STR | AMP | GEN | KANA | VAN | LINE | ERY |

| ATCC19433T | 16R | 32R | 64R | 0.25S | 16R | 16R | 0.25S | 0.25 S | 64S | 1S | 16S | 512S | 1S | 0.5S | 4S |

| HS5152 | > 16R | 128R | 8S | > 8R | 32R | 16R | > 64R | 16R | 256R | 4R | 16S | 512S | 2S | 2S | 1S |

| MGA44-7 | > 16R | 128R | 8S | > 8R | 16R | 4R | 1S | 8R | 256R | 4R | 8S | 256S | 2S | 2S | 2S |

| ELS8-4 | > 16R | 128R | 8S | > 8R | 32R | 2S | 32R | 4R | 256R | 0.032S | 16S | 256S | 2S | 1S | 2S |

| NM15-4 | > 16R | 64R | 8S | > 8R | 16R | 8R | 1S | 16R | 256R | 2S | 32S | 256S | 2S | 2S | 2S |

| HS5302 | > 16R | 64R | 64R | > 8R | 2S | 16R | 64R | 0.125S | 16S | 0.5S | 16S | 128S | 0.5S | 0.5S | 0.25S |

| WZ21-1 | > 16R | 128R | 64R | 1S | 1S | 0.5S | 16R | 0.125S | 32S | 0.5S | 64R | 128S | 0.5S | 0.5S | 0.25S |

| NM31-3 | > 16R | 32R | 64R | 8R | 0.5S | 8R | 0.5S | 0.25S | 32S | 0.5S | 16S | 64S | 0.5S | 0.5S | 0.5S |

| QH9-5 | 16R | 16S | 4S | > 8R | 16R | 2S | 1S | 16R | 128S | 1S | 8S | 128S | 1S | 2S | 2S |

| DM7-2 | > 16R | 32R | 64R | 4R | 1S | 2S | 1S | 0.125S | 32S | 0.5S | 16S | 64S | 0.5S | 0.5S | 0.5S |

| XM26-4 | > 16R | 128R | 64R | 2S | 1S | 2S | 32R | 0.125S | 32S | 1S | 32S | 64S | 0.5S | 0.25S | 0.5S |

| YM11-6 | > 16R | 64R | 64R | 8R | 0.5S | 1S | 1S | 0.125S | 32S | 1S | 16S | 64S | 0.5S | 0.25S | 0.25S |

| YM39-2 | > 16R | 64R | 64R | 8R | 2S | 2S | 0.5S | 0.125S | 8S | 1S | 16S | 64S | 1S | 0.25S | 0.125S |

| QH29-4 | > 16R | 64R | 64R | 0.25S | 1S | 2S | 0.5S | 0.125S | 32S | 1S | 16S | 128S | 1S | 0.5S | 0.25S |

| XJ76305 | > 16R | 128R | 64R | 2S | 2S | 2S | 0.5S | 0.125S | 64S | 1S | 32S | 256S | 0.5S | 0.5S | 0.5S |

| WZ34-2 | > 16R | 16S | 64R | 2S | 1S | 1S | 0.5S | 0.125S | 8S | 0.5S | 16S | 64S | 1S | 0.5S | 0.064S |

| R: resistant; S: susceptible. GEN: Gentamycin, KANA: Kanamycin, STR: Strptomycin, NEO: Neomycin, TET: Tetracycline, CLI: Clindamycin, AMP: Ampicillin, VAN: Vancomycin, QUI: Quinupristin-dalfopristin, LINE: Linezolid, CIP: Ciprofloxcin, ERY: Erythromycin, CHL: Chloramphenicol, TRI: Trimethoprim, RIF: Rifamycin. | |||||||||||||||

表选项

虽然16株菌均出现了不同程度的耐药性,但是不同菌株对抗生素的耐药性存在很大的差异。其中,分离自呼和浩特酸粥样品的菌株HS5152耐药最严重,该菌株对9种抗生素具有耐药性。其次是分离自蒙古国酸牛奶样品的菌株MGA44-78,该菌株对8种抗生素具有耐药性。对抗生素较敏感的菌株XJ76305和菌株QH29-4分别分离自新疆伊犁酸牛奶样品和青海海北州酸牦牛奶样品,它们仅对3种抗生素表现出耐药性。对抗生素最敏感的是分离自内蒙古自巴彦淖尔市酸驼奶的菌株WZ34-2,该菌株仅对克林霉素和氯霉素具有耐药性。

2.2 与耐药性相关的基因 为了深入了解菌株的耐药机制,本研究对16株粪肠球菌耐药表型与基因型进行了关联分析。结果发现9个功能基因与5种抗生素(氯霉素、环丙沙星、甲氧苄啶、新霉素和四环素)存在显著相关关系(表 3)。

表 3. 关联分析所得基因信息 Table 3. Genes associated with antibiotic resistance

| Antibiotic | Genes | Resistant frequency/% (genes/resistant) | Susceptible frequency/% (genes/sensitive) | Correlation with resistance | P-value | Genes function | KEGG | COG |

| CHL | FAM000296 | 100(11/11) | 20(1/5) | Positive | 0.003 | Preprotein translocase subunit SecG | K03075 | COG1314 |

| FAM005768 | 0(0/11) | 80(4/5) | Negative | 0.003 | Preprotein translocase subunit SecG | K03075 | COG1314 | |

| CIP | FAM000296 | 33.3(2/6) | 100(10/10) | Negative | 0.008 | Preprotein translocase subunit SecG | K03075 | COG1314 |

| FAM005768 | 66.7(4/6) | 0(0/10) | Positive | 0.008 | Preprotein translocase subunit SecG | K03075 | COG1314 | |

| FAM002962 | 66.7(4/6) | 0(0/10) | Positive | 0.008 | Conserved hypothetical protein | – | – | |

| TRI | FAM000296 | 20(1/5) | 100(11/11) | Negative | 0.003 | Preprotein translocase subunit SecG | K03075 | COG1314 |

| FAM005768 | 80(4/5) | 0(0/11) | Positive | 0.003 | Preprotein translocase subunit SecG | K03075 | COG1314 | |

| TET | FAM002893 | 80(4/5) | 0(0/11) | Positive | 0.003 | Tetracycline resistance protein tetM | – | COG0480 |

| FAM002894 | 80(4/5) | 0(0/11) | Positive | 0.003 | DNA-binding protein | – | – | |

| FAM002895 | 80(4/5) | 0(0/11) | Positive | 0.003 | RNA polymerase subunit sigma-70 | – | – | |

| NEO | FAM000032 | 100(14/14) | 0(0/2) | Positive | 0.008 | DNA mismatch repair protein MutT | – | K02025 |

| FAM000255 | 100(14/14) | 0(0/2) | Positive | 0.008 | Sugar ABC transporter permease | K02025 | COG4209 | |

| FAM000258 | 100(14/14) | 0(0/2) | Positive | 0.008 | Sensor histidine kinase | – | COG5578 | |

| Positive: Associated with resistance genes exist in the resistant strains; Negative: Associated with resistance genes absence in the resistant strains. | ||||||||

表选项

与氯霉素耐药性呈正相关的基因是FAM000296,呈负相关的基因是FAM005768,这2个基因的功能均为蛋白转位酶亚基SecG (preprotein translocase subunit SecG)。

与环丙沙星抗性相关的基因有3个,其中基因FAM000296与抗性呈负相关性,基因FAM005768和FAM002962与抗性呈正相关性,FAM002962的功能为噬菌体次要结构蛋白(conserved hypothetical protein)。

与甲氧苄啶抗性相关的基因和氯霉素一致,但基因对抗生素抗性的作用不同,基因FAM000296与甲氧苄啶抗性呈负相关性,基因FAM005768与抗性呈正相关性。

有3个基因与四环素抗性相关,且均表现为正相关。其中基因FAM002894和FAM002895的功能分别为DNA结合蛋白(DNA-binding protein)和RNA聚合酶亚基δ-70 (RNA polymerase subunit sigma-70),基因FAM002893功能为四环素抗性蛋白tetM (tetracycline resistance protein tetM),该基因在本研究中发挥的功能与其在CARD数据库比对到的功能一致。

基因FAM000032、FAM000255和FAM000258与新霉素抗性呈显著正相关性,这3个基因功能分别为DNA错配修复蛋白MutT (DNA mismatch repair protein MutT)、ABC转运蛋白通透酶(sugar ABC transporter permease)和传感器组氨酸激酶(sensor histidine kinase)。

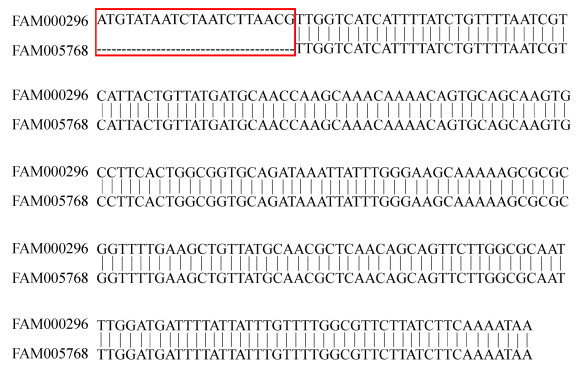

2.3 基因SecG的缺失与菌株的耐药性 上述分析发现,基因FAM000296和FAM005768与氯霉素、环丙沙星和甲氧苄啶的耐药性具有显著相关性。基因FAM000296与氯霉素抗性呈正相关,与环丙沙星和甲氧苄啶抗性呈负相关;而FAM005768与氯霉素抗性呈负相关,与环丙沙星和甲氧苄啶抗性呈正相关。更有趣的是,这2个基因为同源基因,均被注释为SecG。为了进一步分析2个基因的差异,我们比较了2个基因的核苷酸序列,如图 2所示。通过序列比较发现,2个基因的核苷酸序列高度相似,但是,FAM005768相比FAM000296在3′端缺失了21个碱基。这21个碱基编码了7个氨基酸,分别为蛋氨酸、酪氨酸、天冬酰胺、亮氨酸、异亮氨酸、亮氨酸和苏氨酸。

|

| 图 2 基因FAM000296和FAM005768核苷酸序列比较 Figure 2 Genes FAM000296 and FAM005768 nucleotide sequence comparison. |

| 图选项 |

3 讨论 本研究发现发酵食品中分离的粪肠球菌对克林霉素、新霉素、奎奴普丁-达夫普汀和氯霉素具有较高的耐药性,与宋丹丹等[14]、Rizzotti等[15]和Liu等[16]的研究结果一致。其中,对克林霉素100%耐药,这是因为克林霉素为林可酰胺类抗生素,肠球菌对林可酰胺类抗生素具有固有抗性。此外,粪肠球菌对氯霉素的高耐药率可能与氯霉素常用于兽医实践相关,在奶牛治疗中长期使用氯霉素可能是乳制品中粪肠球菌对氯霉素具有较高耐药率的原因之一。粪肠球菌对上述抗生素的高耐药率也提示我们在治疗由粪肠球菌引发的炎症反应中应尽量避免使用上述几种抗生素。

在15种抗生素中,我们发现这16株粪肠球菌对卡那霉素、万古霉素、利奈唑胺和红霉素均无抗性。万古霉素是临床上用于治疗感染的重要的抗菌药物,利奈唑胺也是世界卫生组织用于评估治疗耐万古霉素肠球菌感染的极其重要的抗生素[17],本研究所用粪肠球菌对这两种抗生素均无抗性,相对较安全,与Said等[18]的研究结果一致。此外,红霉素作为大环内酯类抗生素的代表,其抗性一直是一个备受关注的问题。虽然De等[19]已经发现多数粪肠球菌对红霉素表现为中抗或耐药,与本研究结果相异,分析原因可能是由于粪肠球菌样本基数小导致的差异。

与此同时,研究表明甲氧苄啶和环丙沙星抗生素对菌株的抑制效果完全一致,而氯霉素对菌株的抑制效果却与其完全相反。通过关联分析结果显示,基因FAM000296与氯霉素抗性呈正相关性,基因FAM005768与氯霉素抗性呈负相关性,而在与甲氧苄啶和环丙沙星抗性的关联中,FAM000296与甲氧苄啶和环丙沙星抗性呈负相关性,FAM005768与甲氧苄啶和环丙沙星抗性呈正相关性。我们发现,同一菌株中,耐药表型与耐药基因的正负相关性,随着抗生素的不同而存在明显差异,这种差异性反映了菌株的适应性。

值得关注的是,基因FAM000296和FAM005768注释到同一功能SecG,SecG是蛋白Sec体系中的一个转运蛋白,与SecY、SecE形成异源三聚体SecYEG,三聚体SecYEG为前体蛋白过膜通道的主要组成部分[20-21],而SecG在前体蛋白转运和细胞生长中并不是不可或缺的,它仅影响转运的效率。目前,SecG的生化功能还不清楚[12]。SecG与抗生素耐药是否有关,仍是未知数。但本研究却发现SecG可能影响菌株耐药性。虽然FAM000296和FAM005768注释到同一功能但它们的作用却截然相反。我们推测FAM000296和FAM005768极有可能原为同源基因,而FAM005768是基因在进化过程中丢失了编码上述氨基酸的碱基形成的突变。它们对同一抗生素表现出的相反作用可能是由于缺失了7个氨基酸导致其编码蛋白质的空间构象发生了变化[23-25],进而影响了其对抗生素的抗性。这种突变赋予了菌株新的耐药性,与FAM000296相比FAM005768显然拓宽了耐药谱,这种突变对菌株本身可能是有利的,但给人类生产实践带来了一定的风险。当然,这还需要后续的试验进一步验证。

此外,根据试验所用粪肠球菌菌株来源分析,发现菌株耐药性差异较大。分离自自然发酵乳制品的菌株耐药性明显低于其他发酵食品菌株。与此同时,对13株分离自自然发酵乳制品的粪肠球菌耐药情况进行分析,发现分离自酸牛奶的菌株耐药性普遍高于酸马奶、酸驼奶和酸山羊奶等乳制品。分离自酸驼乳的菌株耐药性最低,Jans等[26]报道,驼乳的微生物多样性略低于牛乳,粪肠球菌从其他微生物中获得耐药基因的机会就较少。这可能是导致其耐药性较低的主要原因。

鉴于16株分离自自然发酵乳制品的粪肠球菌在分离源上存在的显著差异性,进一步分析了分离自自然发酵乳制品粪肠球菌的分离地与耐药性的相关性。我们发现,分离自蒙古国和俄罗斯的菌株耐药情况较严重,其中菌株MGA44-7 (蒙古国肯特省)对8种抗生素耐药,菌株ELS8-4 (俄罗斯阿金斯科镇)对7种抗生素耐药;而分离自青海和新疆地区的3株菌耐药性较低。然而,由于样本量较少,采样地点较分散,这种差异并无显著性。

4 结论 本研究全面分析了粪肠球菌对15种抗生素的耐药性,结果发现16株粪肠球菌对卡那霉素、万古霉素、利奈唑胺和红霉素100%敏感;对其余11种抗生素均表现出不同程度的耐药,其中对克林霉素耐药率达到100%。表型与基因组关联分析发现,基因SecG可能影响着氯霉素、甲氧苄啶和环丙沙星的耐药性,基因FAM005768极有可能是FAM000296的突变体,它们对同一抗生素表现出的相反作用可能是由于缺失的7个氨基酸使其对抗生素抗性的表达发生了变化。这表明分离自自然发酵食品的部分粪肠球菌对个别抗生素存在抗性并含有相应的耐药基因。因此,对应用于食品工业的粪肠球菌需进行全面的安全性评估后方可考虑应用。

此外,本研究所用15株粪肠球菌中,有3株耐药性较低的菌株(WZ34-2、XJ76305和QH29-4)可经过进一步的评估应用于食品工业。

References

| [1] | 钟智.肠球菌属模式株比较基因组分析及发酵食品中粪肠球菌多位点序列分型研究.内蒙古农业大学博士学位论文, 2015. |

| [2] | Giraffa G. Functionality of enterococci in dairy products. International Journal of Food Microbiology, 2003, 88(2/3): 215-222. |

| [3] | Joghataei M, Yavarmanesh M, Dovom MRE. Safety evaluation and antibacterial activity of enterococci isolated from lighvan cheese. Journal of Food Safety, 2017, 37(1): e12289. DOI:10.1111/jfs.2017.37.issue-1 |

| [4] | Klibi N, Aouini R, Borgo F, Said LB, Ferrario C, Dziri R, Boudabous A, Torres C, Slama KB. Antibiotic resistance and virulence of faecal enterococci isolated from food-producing animals in Tunisia. Annals of Microbiology, 2015, 65(2): 695-702. DOI:10.1007/s13213-014-0908-x |

| [5] | CLSI. Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically; approved standard. 9th ed. CLSL document M07-A9. Wayne, PA: CLSI, 2012: 90. |

| [6] | CLSL. Performance standards for antimicrobial disk susceptibility tests; approved standard. 11th ed. CLSL document M02-A11. Wayne, PA: CLSI, 2012: 91-94. |

| [7] | ISO. ISO 10932-2010 Milk and milk products: determination of the minimal inhibitory concentration (MIC) of antibiotics applicable to bifidobacteria and non-enterococcal lactic acid bacteria. London: ISO, 2010, 6: 109-132. |

| [8] | FEEDAP. Guidance on the assessment of bacterial susceptibility to antimicrobials of human and veterinary importance. EFSA Journal, 2012, 10(6): 2740. |

| [9] | European Commission, Health & Consumer Protection Directorate-General. Opinion of the scientific committee on animal nutrition on the criteria for assessing the safety of micro-organisms resistant to antibiotics of human clinical and veterinary importance. Brussels: European Commission, 2003. |

| [10] | Brynildsrud O, Bohlin J, Scheffer L, Eldholm V. Rapid scoring of genes in microbial pan-genome-wide association studies with Scoary. Genome Biology, 2016, 17: 238. DOI:10.1186/s13059-016-1108-8 |

| [11] | Kanehisa M, Sato Y, Kawashima M, Furumichi M, Tanabe M. KEGG as a reference resource for gene and protein annotation. Nucleic Acids Research, 2016, 44(D1): D457-D462. DOI:10.1093/nar/gkv1070 |

| [12] | Tatusov RL, Fedorova ND, Jackson JD, Jacobs AR, Kiryutin B, Koonin EV, Krylov DM, Mazumder R, Mekhedov SL, Nikolskaya AN, Rao BS, Smirnov S, Sverdlov AV, Vasudevan S, Wolf YI, Yin JJ, Natale DA. The COG database:an updated version includes eukaryotes. BMC Bioinformatics, 2003, 4: 41. DOI:10.1186/1471-2105-4-41 |

| [13] | McArthur AG, Waglechner N, Nizam F, Yan A, Azad MA, Baylay AJ, Bhullar K, Canova MJ, de Pascale G, Ejim L, Kalan L, King AM, Koteva K, Morar M, Mulvey MR, O'Brien JS, Pawlowski AC, Piddock LJV, Spanogiannopoulos P, Sutherland AD, Tang I, Taylor PL, Thaker M, Wang WL, Yan M, Yu T, Wright GD. The comprehensive antibiotic resistance database. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 2013, 57(7): 3348-3357. DOI:10.1128/AAC.00419-13 |

| [14] | Song DD, Zhang QZ. Clinical distribution and drug resistence of 215 strains of Enterococcus. Journal of Dali University, 2016, 1(2): 48-51. (in Chinese) 宋丹丹, 张群智. 215株肠球菌的临床分布与耐药性分析. 大理大学学报, 2016, 1(2): 48-51. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1672-2345.2016.02.014 |

| [15] | Rizzotti L, Rossi F, Torriani S. Biocide and antibiotic resistance of Enterococcus faecalis and Enterococcus faecium isolated from the swine meat chain. Food Microbiology, 2016, 60: 160-164. DOI:10.1016/j.fm.2016.07.009 |

| [16] | Flórez AB, Mayo B. Antibiotic resistance-susceptibility profiles of Streptococcus thermophilus isolated from raw milk and genome analysis of the genetic basis of acquired resistances. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2017, 8: 2608. DOI:10.3389/fmicb.2017.02608 |

| [17] | Kürekci C, ?nen SP, Yipel M, Aslanta? ?, Gündo?du A. Characterisation of phenotypic and genotypic antibiotic resistance profile of Enterococci from cheeses in turkey. Korean Journal for Food Science of Animal Resources, 2016, 36(3): 352-358. DOI:10.5851/kosfa.2016.36.3.352 |

| [18] | Said LB, Klibi N, Dziri R, Borgo F, Boudabous A, Slama KB, Torres C. Prevalence, antimicrobial resistance and genetic lineages of Enterococcus spp. from vegetable food, soil and irrigation water in farm environments in Tunisia. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 2016, 96(5): 1627-1633. DOI:10.1002/jsfa.2016.96.issue-5 |

| [19] | Chotinantakul K, Chansiw N, Okada S. Antimicrobial resistance of Enterococcus spp. isolated from Thai fermented pork in Chiang Rai Province, Thailand. Journal of Global Antimicrobial Resistance, 2018, 12: 143-148. DOI:10.1016/j.jgar.2017.09.021 |

| [20] | 白雷雷.基因修饰增加枯草芽孢杆菌脂肪酶的分泌.天津大学硕士学位论文, 2015. |

| [21] | Park E, Ménétret JF, Gumbart JC, Ludtke SJ, Li WK, Whynot A, Rapoport TA, Akey CW. Structure of the SecY channel during initiation of protein translocation. Nature, 2014, 506(7486): 102-106. DOI:10.1038/nature12720 |

| [22] | Zhang Y, Yang KG. Escherichia coli Sec-dependent protein transport pathways. Progress in Microbiology and Immunology, 2000, 28(4): 64-68. (in Chinese) 张友, 杨克恭. 大肠杆菌Sec依赖性蛋白质转运途径. 微生物学免疫学进展, 2000, 28(4): 64-68. |

| [23] | Zhang F, Zhang Q, Lin B, Cai SF, Zhu ZM, Zhou TL. Analysis of virus mutation in blood donors with occult hepatitis B infection. Chinese Journal of Health Laboratory Technology, 2017, 27(6): 804-807. (in Chinese) 张锋, 张琼, 林碧, 蔡淑锋, 朱紫苗, 周铁丽. 无偿献血者隐匿性乙肝感染病毒变异检测分析. 中国卫生检验杂志, 2017, 27(6): 804-807. |

| [24] | Altukhov DA, Talyzina AA, Agapova YK, Vlaskina AV, Korzhenevskiy DA, Bocharov EV, Rakitina TV, Timofeev VI, Popov VO. Enhanced conformational flexibility of the histone-like (HU) protein from Mycoplasma gallisepticum. Journal of Biomolecular Structure and Dynamics, 2018, 36(1): 45-53. DOI:10.1080/07391102.2016.1264893 |

| [25] | Su MG, Weng JTY, Hsu JBK, Huang KY, Chi YH, Lee TY. Investigation and identification of functional post-translational modification sites associated with drug binding and protein-protein interactions. BMC Systems Biology, 2017, 11(S7): 132. DOI:10.1186/s12918-017-0506-1 |

| [26] | Jans C, Bugnard J, Njage PMK, Lacroix C, Meile L. Lactic acid bacteria diversity of African raw and fermented camel milk products reveals a highly competitive, potentially health-threatening predominant microflora. LWT-Food Science and Technology, 2012, 47(2): 371-379. DOI:10.1016/j.lwt.2012.01.034 |