刘杨1, 周之超2, 顾继东2, 李猛1

1.深圳大学高等研究院, 广东 深圳 518000;

2.香港大学生物科学学院, 香港 999077

收稿日期:2018-01-22;修回日期:2018-03-17;网络出版日期:2018-03-23

基金项目:国家自然科学基金(31700430,31622002);中国博士后科学基金面上资助(2017M612718);广东省自然科学基金博士启动项目(2017A030310296)

作者简介:李猛, 深圳大学****。2011年于香港大学获得博士学位, 2016年入选中组部"青年千人"和国家基金委"优秀青年"人才项目。目前担任国际微生物生态学会(ISME)地区青年大使、中国微生物学会环境微生物专业委员会和地质微生物专业委员会委员、Applied and Environmental Biotechnology和《生物工程学报》编委, Frontiers in Microbiology审稿编辑等职。主要从事环境微生物组学研究, 结合微生物生态学和生物信息学等多学科交叉的理论和技术, 研究微生物驱动元素地球化学循环的机制, 在发掘环境中未培养古菌的生理代谢机制及其生态功能等方面取得系列成果, 相关工作被国际同行在Nature、Science和Cell等杂志多次引用。先后主持了国家基金委、广东省和深圳市等多项重要科研课题, 已在Nature Microbiology, Nature Communications, The ISME Journal等期刊发表文章40余篇, 引用次数超过1300次, H-index为20

*通信作者:李猛, Tel:+86-755-26979250;E-mail:limeng848@szu.edu.cn

摘要:[目的]初步探究海洋线虫与微生物的相互作用对碳、氮循环的影响。[方法]利用16S rRNA和18S rRNA基因高通量测序方法,对33个近岸沉积物样品中细菌、古菌和真核生物的多样性进行调查;对海洋线虫与细菌、海洋线虫与古菌的共现性进行网络分析,并采用Spearman统计学方法,识别出与海洋线虫共现性呈显著相关性的微生物种类。[结果]在夏季,红树林和潮间带泥滩样品中线虫OTU平均相对丰度基本呈随深度增加而递减趋势;冬季的红树林样品中发现相类似变化规律,只有在冬季潮间带泥滩样品中线虫OTU平均相对丰度在深层较高于表层。相对丰度最高的海洋线虫隶属于单宫目(47%)、色矛目(19%)、刺嘴目(16%)和垫刃目(9%),它们与热源体古菌、深古菌、γ-和δ-变形菌等微生物有显著正/负相关关系。[结论]在香港米埔湿地沉积物中,与相对丰度最高的5种线虫显著相关的几大类微生物均在碳、氮、硫等元素循环方面起十分重要的作用,暗示海洋线虫与微生物潜在的相互作用对元素地球化学循环具有重要影响。研究结果有助于深入了解线虫在生态系统中未被揭示的生态功能,有助于更清晰地认识海洋线虫在底栖生态系统中所扮演的角色。

关键词: 海洋线虫 细菌 古菌 元素循环 近岸沉积物

Effect of co-occurrence of marine nematodes and microbes on carbon and nitrogen cycles in coastal sediments

Yang Liu1, Zhichao Zhou2, Jidong Gu2, Meng Li1

1.Institute for Advanced Study, Shenzhen University, Shenzhen 518000, Guangdong Province, China;

2.School of Biological Sciences, The University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong 999077, China

Received 22 January 2018; Revised 17 March 2018; Published online 23 March 2018

*Corresponding author: Meng Li, Tel: +86-755-26979250; E-mail: limeng848@szu.edu.cn

Supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31700430, 31622002), by the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2017M612718) and by the Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province (2017A030310296)

Abstract: [Objective]This study is aimed to investigate the interaction effects of marine free-living nematodes and microbes on carbon and nitrogen cycles in coastal sediments.[Methods]We used 16S rRNA and 18S rRNA high-throughput sequencing technology to inspect the diversity and community of bacteria, archaea and eukaryotes in 33 coastal sediment samples. The Spearman correlation method was adapted to analyze the co-occurrence pattern between marine nematodes and microbes (bacteria and archaea), to recognize the microbial group with significant correlation with nematodes.[Results]In summer, the average relative abundance of nematode OTUs decreased with the increasing depths both in mangrove and intertidal mudflat sediments. Similar pattern was discovered in winter samples with one exception that the averaged relative abundance of nematode OTUs in deeper layer was significantly higher than that in upper layer. The five most abundant marine nematode OTUs belong to Monhysterida (47%), Chromadorida (19%), Enoplia (16%) and Tylenchida (9%). Those OTUs are significantly correlated with Thermoplasmata, Bathyarchaeota, gamma-and delta-Proteobacteria.[Conclusion]In the wetland sediments sampled from Mai Po Nature Reserve of Hong Kong, the microbes those have significant correlation with nematodes play important roles in carbon, nitrogen and sulfur cycles. It implies that the potential interaction effects between marine nematodes and microbes have crucial impacts on biogeochemical cycles. Our results could help us to uncover the ecological function of nematodes in the environments, to better understand the roles of marine nematodes in the benthic ecosystems.

Key words: marine nematodes bacteria archaea biogeochemical cycles coastal sediments

小型底栖动物是底栖环境中体长在35-500 μm的无脊椎动物类群,其在生态系统中具有很高的生产力(海洋系统[1]:0.003-38.800 g C/m2·a;淡水系统[2]:0.8-10.0 g C/m2·a)。其中,海洋自由生活线虫是分布最为广泛、数量最为丰富、多样性最高的一类[3],它们在海洋沉积物中的密度通常为1×106-12×106个/米2[4-5],在近岸环境中其可占小型底栖动物总数量的60%-90%[6]。近岸沉积物中汇聚了包括氮、碳、磷等元素在内的丰富的营养物质,为底栖生物提供了充足生长物质来源[7-8]。

目前,国际上关于小型底栖动物在底栖生态系统的活动过程及其在底栖系统服务中所扮演角色的研究十分有限[9],很少有研究关注小型底栖动物对物质循环,尤其是海洋线虫对于碳、氮循环的影响。研究表明由底栖微生物、小型底栖动物组成的“微食物网”对生态系统中所有可用有机物质的消耗量可占据70%-80%[10]。最新研究显示,某些种类的小型底栖动物在食物网中的营养位和大型底栖动物相当,甚至更高[11-12]。该结果一方面质疑了“食物网是静态的,且营养位随生物体长增长而增长”的假设,另一方面凸显了小型底栖动物在食物网中常被忽略的重要角色。海洋线虫可通过对微生物的摄食活动及生物扰动活动,影响海洋生态系统中碳、氮等元素循环过程[13-14]。因此,研究沉积物中海洋自由生活线虫与微生物相互作用对元素生物地球化学循环的影响是非常必要的,有助于深入了解线虫在海洋环境中未被揭示的生态功能。

本研究利用16S rRNA和18S rRNA基因高通量测序方法,对33个红树林近岸沉积物样品中细菌、古菌和真核生物的多样性进行了调查,构建了海洋线虫与细菌、海洋线虫与古菌的共现性网络,确定了海洋线虫与细菌、古菌的显著共现关系,描绘出海洋线虫与微生物相互作用的概貌,并初步探究了海洋线虫与微生物的相互作用对碳、氮循环的影响,为后续研究奠定基础。

1 材料和方法 1.1 样品采集、理化参数测定及DNA提取 本研究所采用的沉积物样品是从香港米埔自然保护区的近岸湿地采集的,如图 1。共6个站位,其中3个来自红树林(MG1-3),3个来自潮间带泥滩(TF1-3)。在冬夏两季进行了纵向分层采样,其中红树林样品分别分了4层(冬季,Win,表层至底层:A-D)和3层(夏季,Sum,表层至底层:A-C),潮间带泥滩样品均分了2层(表 1,A-B)。沉积物样品在采集后立即密封并放入冷冻盒保存。每个样品中取0.25 g湿重沉积物用来提取DNA。采用PowerSoil?DNA提取试剂盒,参照说明书对样品进行DNA提取。具体信息可参考文献[15]。

|

| 图 1 米浦湿地采样点的卫星示意图 Figure 1 Satellite map depicting Mai Po area and sampling locations. |

| 图选项 |

表 1. 个样品的采样点信息、18S rRNA基因测序信息及alpha多样性数据 Table 1. Sampling information, 18S rRNA gene sequencing information and alpha diversity values on 33 samples

| Sample name | Sampling position | Depth/cm | pH | Raw tags No. | Clean tags No. | OTU No. | Alpha diversity | |||

| Shannon index | ACE | Chao1 | Good’s coverage/% | |||||||

| MG1WinA | 22°29.665'N, 114°01.742'E | 0-2 | 7.07 | 164771 | 151635 | 10783.0 | 7.1 | 32169.8 | 29905.3 | 95.2 |

| MG1WinB | 10-15 | 6.38 | 83345 | 63789 | 7908.0 | 9.0 | 24362.2 | 23484.2 | 91.7 | |

| MG1WinC | 20-25 | 7.21 | 202851 | 188107 | 9169.0 | 6.0 | 30065.3 | 27948.0 | 96.7 | |

| MG1WinD | 40-45 | 7.60 | 109888 | 88884 | 6116.0 | 6.8 | 21849.6 | 19555.3 | 95.2 | |

| MG2WinA | 22°29.709'N, 114°01.812'E | 0-2 | 7.11 | 262456 | 252380 | 12327.0 | 6.1 | 32613.5 | 32582.3 | 96.9 |

| MG2WinB | 10-15 | 6.41 | 341526 | 233951 | 20760.0 | 9.7 | 72706.2 | 71205.7 | 93.9 | |

| MG2WinC | 20-25 | 6.84 | 535931 | 444189 | 28066.0 | 8.3 | 80349.3 | 80363.7 | 95.8 | |

| MG2WinD | 40-45 | 7.13 | 319584 | 319068 | 24644.0 | 8.8 | 77532.0 | 74795.0 | 94.8 | |

| MG3WinA | 22°29.762'N, 114°01.866'E | 0-2 | 6.41 | 349445 | 348681 | 25645.0 | 8.2 | 78420.8 | 77951.9 | 95.0 |

| MG3WinB | 10-15 | 6.27 | 390368 | 298445 | 17719.0 | 6.4 | 54425.6 | 56397.6 | 96.0 | |

| MG3WinC | 20-25 | 6.79 | 651598 | 575509 | 27633.0 | 6.6 | 91332.3 | 87157.5 | 96.7 | |

| MG3WinD | 40-45 | 7.40 | 659655 | 570376 | 30364.0 | 8.0 | 95982.5 | 90081.4 | 96.4 | |

| TF1WinA | 22°29.676'N, 114°01.706'E | 0-5 | 7.06 | 1228320 | 1185230 | 24847.0 | 4.3 | 70252.2 | 70803.9 | 98.7 |

| TF1WinB | 13-16 | 7.68 | 358872 | 279182 | 17908.0 | 7.5 | 53783.8 | 53913.2 | 95.7 | |

| TF2WinA | 22°29.726'N, 114°01.799'E | 0-5 | 7.45 | 1112432 | 1070530 | 30319.0 | 5.9 | 80930.9 | 84256.4 | 98.2 |

| TF2WinB | 13-16 | 7.77 | 87491 | 87345 | 9181.0 | 8.0 | 27190.4 | 26585.2 | 93.0 | |

| TF3WinA | 22°29.951'N, 114°01.651'E | 0-5 | 7.02 | 211145 | 130551 | 8533.0 | 6.8 | 23700.0 | 22837.1 | 95.7 |

| TF3WinB | 13-16 | 7.52 | 116565 | 116379 | 10915.0 | 7.8 | 32622.7 | 32190.2 | 93.7 | |

| MG1SumA | 22°29.665'N, 114°01.726'E | 0-2 | 6.68 | 304282 | 267065 | 19604.0 | 7.7 | 60716.9 | 59178.1 | 95.0 |

| MG1SumB | 10-15 | 7.58 | 333212 | 307936 | 27243.0 | 9.2 | 80659.2 | 78807.0 | 94.1 | |

| MG1SumC | 20-25 | 7.90 | 124781 | 124626 | 16225.0 | 9.7 | 51088.6 | 49866.6 | 91.1 | |

| MG2SumA | 22°29.704'N, 114°01.814'E | 0-2 | 5.82 | 337234 | 313946 | 25960.0 | 9.5 | 98849.8 | 88838.3 | 94.1 |

| MG2SumB | 10-15 | 6.87 | 222251 | 162739 | 15148.0 | 8.2 | 51126.7 | 47642.9 | 93.5 | |

| MG2SumC | 20-25 | 6.84 | 308159 | 259515 | 19965.0 | 7.9 | 66506.5 | 64372.7 | 94.7 | |

| MG3SumA | 22°29.875'N, 114°01.767'E | 0-2 | 6.60 | 861442 | 826093 | 24450.0 | 4.9 | 79451.7 | 80107.1 | 98.0 |

| MG3SumB | 10-15 | 7.31 | 834775 | 794436 | 25470.0 | 5.5 | 85674.9 | 83892.3 | 97.8 | |

| MG3SumC | 20-25 | 7.32 | 109010 | 108864 | 14223.0 | 9.6 | 44868.6 | 42034.8 | 91.1 | |

| TF1SumA | 22°29.679'N, 114°01.709'E | 0-5 | 7.10 | 644737 | 609389 | 24681.0 | 6.2 | 70324.8 | 71240.6 | 97.4 |

| TF1SumB | 13-16 | 7.86 | 39849 | 24893 | 4955.0 | 9.3 | 16816.2 | 15780.8 | 86.0 | |

| TF2SumA | 22°29.718'N, 114°01.786'E | 0-5 | 7.38 | 251469 | 232317 | 13554.0 | 7.0 | 38031.4 | 36742.5 | 96.2 |

| TF2SumB | 13-16 | 8.17 | 63467 | 63385 | 7528.0 | 8.5 | 25642.2 | 24289.5 | 91.7 | |

| TF3SumA | 22°29.949'N, 114°01.656'E | 0-5 | 7.31 | 120057 | 116618 | 12378.0 | 8.5 | 37582.5 | 35829.7 | 92.8 |

| TF3SumB | 13-16 | 7.81 | 61702 | 61616 | 7152.0 | 8.6 | 23842.6 | 24050.4 | 92.0 | |

| For the information on bacteria and archaeal 16S rRNA genes, please see in Supplementary Table 4 in the reference [15]. | ||||||||||

表选项

1.2 16S rRNA和18S rRNA基因的引物扩增及高通量测序 为了得到古菌特有16S rRNA基因库,本研究采用嵌套式PCR流程,第一步长片段引物为21F/958R,在获得纯化后的PCR产物后,采用Arch349F/Arch806R引物进行第二步PCR。对于细菌16S rRNA基因建库,本研究采用515F/909R引物,覆盖了16S的V4-V5高变区。具体信息详见本课题组已发表文献[15]。对于18S rRNA基因建库,本研究采用1380F/1510R引物,覆盖了18S的V9高变区,随后的标准化PCR扩增等流程由北京诺禾致源公司完成。本研究采用Illumina MiSeq高通量测序平台(北京诺禾致源公司)。

1.3 测序数据分析 采用修改后的vsearch标准流程(https://github.com/torognes/vsearch/wiki/VSEARCH-pipeline)对细菌和古菌的16S rRNA以及18S rRNA基因测序数据进行分析,得到OTU后,采用QIIME[16]的assign_taxonomy.py (SILVA SSU v128数据库,97%相似度)和make_otu_table.py对OTU进行分类学分析和构建OTU表。18S rRNA基因和细菌、古菌的16S rRNA基因的OTU数据采用dada2包[17]的rarefy_even_depth函数进行均一化。对33个样品的18S rRNA基因数据和细菌、古菌的16S rRNA基因数据进行均一化后,将每一个线虫OTU在33个样品中的相对丰度数值与每一个细菌、古菌OTU的相对丰度数值进行Spearman相关性计算[18],通过P值是否小于0.05来判断相关性是否显著,通过ρ值是否大于0.33/小于-0.33判断是否显著正/负相关[19]。线虫OTU的相对丰度为某个线虫OTU的绝对丰度之于所有18S rRNA OTU的绝对丰度之和的百分比值(图 2-A),线虫OTU种群内的相对丰度为某个线虫OTU的绝对丰度之于所有线虫OTU绝对丰度之和的百分比值(图 2-B)。

|

| 图 2 在红树林和潮间带泥滩样品中,不同季节、深度样品中线虫OTU的平均相对丰度 Figure 2 The averaged relative abundance of nematode OTUs in different seasons and sediment depths from mangrove and tidal flat samples. Error bar stands for standard deviation values. |

| 图选项 |

2 结果和分析 在对33个样品的18S rRNA基因的高通量测序结果进行均一化后,共获得属于线虫动物门的119个OTU,其中OTU_21、OTU_17、OTU_29、OTU_14和OTU_15是相对丰度最高的5个,其序列总数占所有线虫动物门OTU序列总数的58.5%。如图 2所示,在夏季,红树林和潮间带泥滩样品中线虫OTU平均相对丰度基本呈随深度增加而递减趋势,在冬季的红树林样品中亦是,只有在冬季潮间带泥滩样品中线虫OTU平均相对丰度在深层是较高于表层的。

2.1 线虫在目水平上的相对丰度和群落组成 从33个样品18S rRNA基因的测序结果可以看出(图 3),在目水平上,单宫目(Monhysterida)线虫是最优势种,其OTU数量在所有样品的线虫OTU中平均所占比为47%,并在所有样品中均有出现(图 3)。在潮间带泥滩样品中,冬季单宫目线虫OTU平均相对丰度要高于夏季,但在红树林湿地中则相反,且相较于红树林样品,单宫目线虫OTU总数要高于潮间带泥滩样品。其次,色矛目(Chromadorida)和刺嘴目(Enoplida)线虫OTU相对丰度也较高,其数量在所有样品的线虫OTU中平均所占比分别为19%和16%。其中,色矛目线虫在冬季的红树林样品中OTU平均相对丰度最多,但冬季潮间带泥滩样品却最少,而刺嘴目线虫的OTU平均相对丰度在冬季的红树林和潮间带泥滩样品中均高于夏季样品。此外,垫刃目线虫(Tylenchida) OTU在所有样品的线虫OTU中平均所占比为9%,在夏季红树林样品中数量最高,夏季潮间带泥滩样品次之,而在冬季样品中鲜见。

|

| 图 3 线虫群落分类图 Figure 3 Bar chart of taxonomic profiles of nematode community at order level. A: Relative abundance of nematodes at order level; B: Relative abundance of the nematode population. |

| 图选项 |

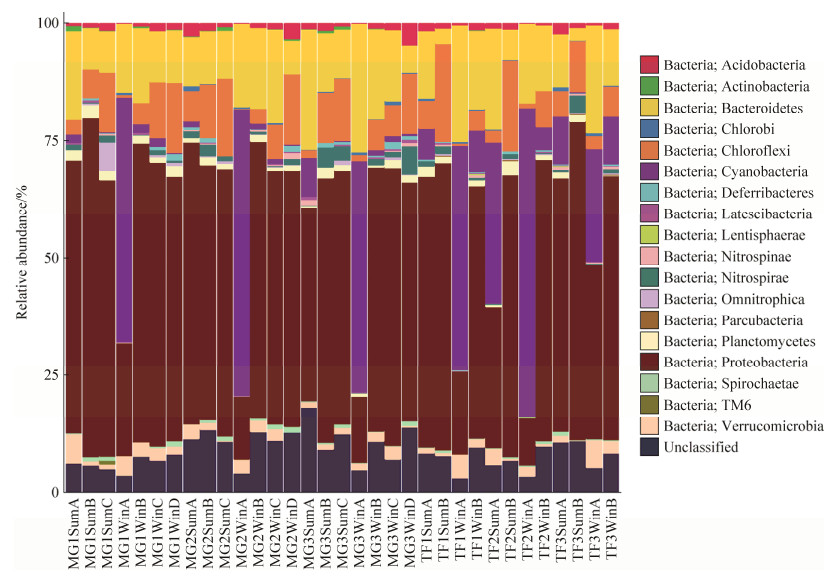

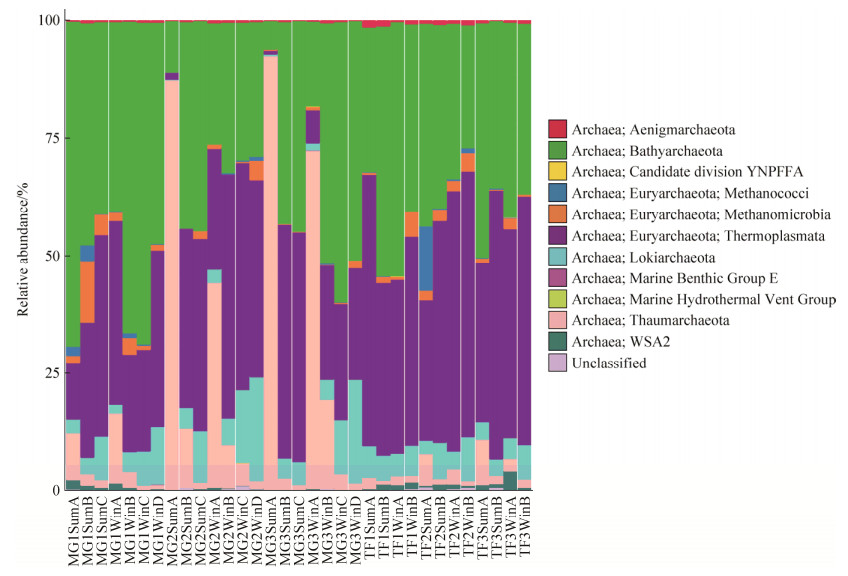

2.2 细菌和古菌在门/纲水平上的相对丰度和群落组成 细菌和古菌的群落组成和相对丰度的16S rRNA基因测序结果如图 4、5显示。相对丰度最高的细菌包括变形菌门(Proteobacteria,52%)、拟杆菌门(Bacteroidetes,15%)、蓝菌门(Cyanobacteria,12%)、绿弯菌门(Chloroflexi,9%)和浮霉菌门(Planctomycetes,2%)。相对丰度最高的古菌包括深古菌(Bathyarchaeota,41%)、热源体菌(Thermoplasmata,36%)、奇古菌(Thaumarchaeota,13%)、洛基古菌(Lokiarchaeota,7%)和甲烷微古菌(Methanomicrobia,2%)。这5种古菌的相对丰度之和占古菌总量的近99%。

|

| 图 4 细菌在门/纲水平上的相对丰度 Figure 4 Bar chart of taxonomic profiles of bacterial community at phylum/order level. |

| 图选项 |

|

| 图 5 古菌在门/纲水平上的相对丰度 Figure 5 Bar chart of taxonomic profiles of archaeal community at phylum/order level. |

| 图选项 |

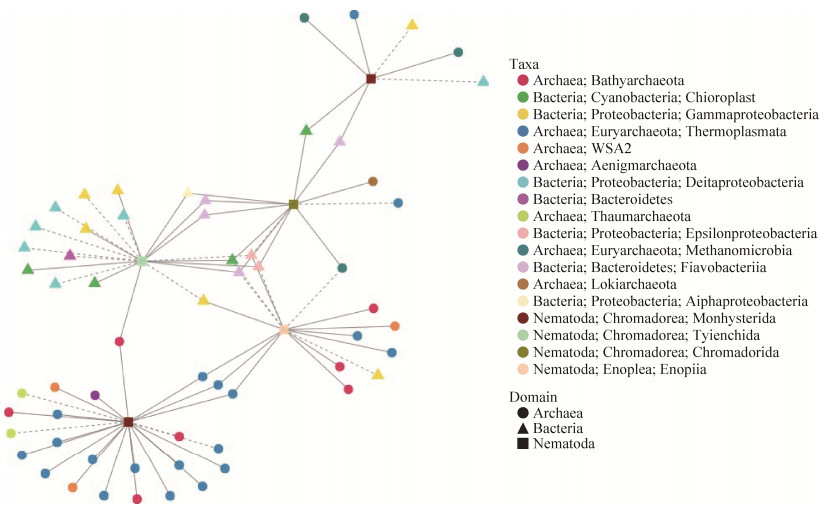

2.3 线虫与细菌、古菌共现关系网络分析 总共有60个细菌和古菌OTU与这5个线虫OTU呈显著相关关系。其中,39个细菌和古菌OTU只与线虫OTU呈显著正相关关系,主要包括热源体古菌(17)、深古菌(6)、WSA2古菌(3)、黄杆菌(3)和蓝细菌(3);而其中15个细菌和古菌OTU只与线虫OTU呈显著负相关关系,包括δ变形菌(6)、γ变形菌(3)、热源体古菌(2)、奇古菌(2)、深古菌(1)和拟杆菌(1)。

如图 6显示,相对丰度最高的5个线虫OTU分属于单宫目(OTU_21和OTU_29)、色矛目(OTU_14)、刺嘴目(OTU_15)和垫刃目(OTU_17)。OTU_21 (单宫目)与24种细菌和古菌呈显著相关关系,包括与热源体古菌、深古菌和WSA2古菌呈显著正相关关系,与奇古菌呈显著负相关关系。OTU_17 (垫刃目)与20种细菌、古菌呈显著相关关系,其中,OTU_17 (垫刃目)主要与γ变形菌、蓝细菌和黄杆菌有显著正相关关系,主要与δ变形菌、绿弯菌和γ变形菌呈显著负相关关系。OTU_15 (刺嘴目)与16种细菌、古菌呈显著相关关系,主要包括与深古菌和热源体古菌呈显著正相关关系,与变形菌呈显著负相关关系。OTU_14 (色矛目)与12种细菌、古菌呈显著相关关系,包括与黄杆菌和蓝细菌呈显著正相关关系,与变形菌和热源体古菌呈显著负相关关系。OTU_29 (单宫目)与7种细菌、古菌呈显著相关关系,包括与甲烷微古菌呈显著正相关关系,与变形菌呈显著负相关关系。

|

| 图 6 线虫与细菌、古菌的共现网络图 Figure 6 The co-occurrence network between nematodes and bacteria/archaea. Solid lines indicate significantly positive correlations, dashed lines indicate significantly negative correlations. |

| 图选项 |

3 讨论 本研究分析了香港米埔湿地自然保护区冬夏两季,共33个湿地沉积物样品中线虫与细菌、古菌的共现性关系,试图找出受线虫活动影响的细菌、古菌类群,从而将线虫的摄食、生物扰动活动与微生物的代谢功能联系起来,初步探究线虫在湿地沉积物中碳、氮元素循环中扮演的重要角色。

蔡立哲等[20]于1997年对深圳河口福田泥滩与红树林进行了自由生活海洋线虫的生态调查,共采到28种海洋线虫,分别隶属于单宫目、色矛目和刺嘴目,与本研究所得的线虫种类类似,唯一区别是本研究还检测到了垫刃目线虫的存在。该研究的采样点与本研究的采样点毗邻,属于同一区域,因此具有可比性。目前国际上依赖于DNA条形码,例如分子标记基因(18S rRNA或COI),正逐渐做为形态学鉴定调查海洋线虫多样性的辅助手段[21-22]。由于缺乏形态学鉴定结果,本研究对海洋线虫的调查无法直接代表该样品中线虫的真正多样性和丰度,但对于后续研究具有指导意义。

从与5个相对丰度最高的线虫OTU呈显著相关关系的微生物类群的数量和分布上可以看出,包括热源体古菌、深古菌、WSA2古菌和奇古菌在内的古菌类群在OTU数量上,意外地比细菌多。我们推测,在海洋生态环境中绝对丰度不占优势的古菌类群,与海洋线虫产生的如此联系很有可能对海洋环境的元素循环产生此前所被忽视的重要影响。

热源体古菌是米埔湿地中相对丰度仅次于深古菌的古菌类群,但其是与5个相对丰度最高的线虫OTU呈显著正相关关系最多的微生物类群。热源体古菌是一类未培养古菌,隶属于广古菌门,其广泛分布于全球海洋中[23]。根据基因组功能预测[23-24],热源体古菌具有胞外蛋白降解酶、产乙酸、产氢气、糖类发酵等代谢功能,对沉积物中碳循环起到十分重要的作用。

深古菌是米埔湿地中相对丰度最高的古菌类群,其中很多与5个相对丰度最高的线虫OTU呈显著关系。深古菌是最近命名的一个新的古菌门[25],该古菌类群具有种群多样性高、代谢多样性高的特点。目前深古菌可分为23个亚群,具有多种生理生化功能,能降解蛋白质、多聚碳水化合物、脂肪酸、芳香族化合物和甲基化合物等有机质,参与甲烷代谢循环,产乙酸,异化还原亚硝酸盐和硫酸盐,对沉积物中碳、氮、硫循环均可能具有重要的驱动作用[26]。

变形菌是米埔湿地中相对丰度最高的细菌,其中的γ-和δ-变形菌是主要与线虫OTU有显著相关关系的类群。γ变形菌中以黄单胞菌(Xanthomonadales)和着色菌(Chromatiales)为优势类群,δ变形菌中以脱硫菌(Desulfobacterales)为最优势类群。黄单胞菌是最大的植物病原菌类群之一,为专性需氧菌。但在米埔湿地沉积物中的黄单胞菌绝大多数属于JTB255-MBG类群,根据最新研究显示[27],该菌在全球海洋沉积物中广泛分布,并在欧洲和澳大利亚近岸沉积物中分别占总细胞数的22%和6%。根据目前唯一的分离纯菌和基因组信息预测,该菌可进行好氧和厌氧呼吸,为异养兼性化能自养型细菌,并具有反硝化功能[27-28]。根据重建的16S rRNA基因进化树分析[27],该菌应隶属于着色菌目Woeseiaceae属,而非黄单胞菌目。此外,大部分着色菌和脱硫菌主要以硫的代谢为主要能量来源(硫化物氧化)或者硫酸盐为主要的电子受体(硫酸盐还原等),其中着色菌中也有可在氧化硫化物时进行固氮和乙炔还原活动[29-31]。

分析结果表明在米埔湿地沉积物中,与相对丰度最高的5种线虫显著相关的几大类微生物均在碳、氮、硫等元素循环方面起到十分重要的作用。因此,研究沉积物中海洋自由生活线虫与微生物相互作用对元素生物地球化学循环的影响非常必要,有助于深入了解线虫在生态系统中未被揭示的生态功能。早先针对土壤食细菌线虫对土壤中碳、氮矿化的促进作用的研究并不鲜见[32-34],但均采用特定线虫类群及其喜好的微生物作为研究系统。随后,也出现了以整个土壤生态系统为研究对象的研究结果,称线虫类群的多寡并未显著影响土壤中碳的矿化[35]。另外,有科学家对海洋沉积物中以海洋线虫为优势类群的小型底栖动物为研究对象,发现其生物扰动活动会通过下行效应改变微生物群落,虽显著降低多环芳烃的矿化[36],但可以显著提高有机物质的矿化[13],此外亦可提高反硝化作用[14]。因此,在底栖生态系统中,包括海洋线虫在内的小型底栖动物类群对生物地球化学循环的影响已经得到了少量研究的证实,但对于影响机制的研究尚无报道。

本文从整个湿地沉积物生态系统的角度出发,通过网络分析的方法探索了湿地沉积物中线虫与不同微生物类群的潜在相互作用,结果发现线虫与古菌有着较为丰富的共现性关系,而且与线虫有显著关系的微生物类群均在碳、氮循环中扮演重要角色。本研究所建立的线虫与微生物的共现性关系,可为将来深入研究“线虫-微生物-元素循环”这一相互作用机理打下基础,从而更加清晰地认识海洋线虫在底栖生态系统中所扮演的角色。

References

| [1] | Burd BJ, Macdonald TA, van Roodselaar A. Towards predicting basin-wide invertebrate organic biomass and production in marine sediments from a Coastal Sea. PLoS One, 2012, 7(7): e40295. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0040295 |

| [2] | Reiss J, Schmid-Araya JM. Life history allometries and production of small fauna. Ecology, 2010, 91(2): 497-507. DOI:10.1890/08-1248.1 |

| [3] | Du YF, Gao S, Warwick RM, Hua E. Ecological functioning of free-living marine nematodes in coastal wetlands:an overview. Chinese Science Bulletin, 2014, 59(34): 4692-4704. DOI:10.1007/s11434-014-0592-z |

| [4] | Heip CHR, Vincx M, Vranken G. The ecology of marine nematodes. Oceanography and Marine Biology-An Annual Review, 1985, 23: 399-489. |

| [5] | Soetaert K, Vincx M, Wittoeck J, Tulkens M. Meiobenthic distribution and nematode community structure in five European estuaries. Hydrobiologia, 1995, 311(1/3): 185-206. |

| [6] | Cai LZ. Progresson marine benthic ecology and biodiversity. Journal of Xiamen University (Natural Science), 2006, 45(S2): 83-89. (in Chinese) 蔡立哲. 海洋底栖生物生态学和生物多样性研究进展. 厦门大学学报(自然科学版), 2006, 45(S2): 83-89. |

| [7] | Sanders CJ, Eyre BD, Santos IR, Machado W, Luiz-Silva W, Smoak JM, Breithaupt JL, Ketterer ME, Sanders L, Marotta H, Silva-Filho E. Elevated rates of organic carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus accumulation in a highly impacted mangrove wetland. Geophysical Research Letters, 2014, 41(7): 2475-2480. DOI:10.1002/2014GL059789 |

| [8] | Alfaro AC. Benthic macro-invertebrate community composition within a mangrove/seagrass estuary in northern New Zealand. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, 2006, 66(1/2): 97-110. |

| [9] | Schratzberger M, Ingels J. Meiofauna matters:The roles of meiofauna in benthic ecosystems. Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology, 2017. DOI:10.1016/j.jembe.2017.01.007 |

| [10] | Mitsch WJ, Gosselink JG. The value of wetlands:importance of scale and landscape setting. Ecological Economics, 2000, 35(1): 25-33. DOI:10.1016/S0921-8009(00)00165-8 |

| [11] | Evrard V, Soetaert K, Heip CHR, Huettel M, Xenopoulos MA, Middelburg JJ. Carbon and nitrogen flows through the benthic food web of a photic subtidal sandy sediment. Marine Ecology Progress Series, 2010, 416: 1-16. DOI:10.3354/meps08770 |

| [12] | Schmid-Araya JM, Schmid PE, Tod SP, Esteban GF. Trophic positioning of meiofauna revealed by stable isotopes and food web analyses. Ecology, 2016, 97(11): 3099-3109. DOI:10.1002/ecy.1553 |

| [13] | Nascimento FJA, N?slund J, Elmgren R. Meiofauna enhances organic matter mineralization in soft sediment ecosystems. Limnology and Oceanography, 2012, 57(1): 338-346. DOI:10.4319/lo.2012.57.1.0338 |

| [14] | Bonaglia S, Nascimento FJA, Bartoli M, Klawonn I, Brüchert V. Meiofauna increases bacterial denitrification in marine sediments. Nature Communications, 2014, 5: 5133. DOI:10.1038/ncomms6133 |

| [15] | Zhou ZC, Meng H, Liu Y, Gu JD, Li M. Stratified bacterial and archaeal community in mangrove and intertidal wetland mudflats revealed by high throughput 16S rRNA gene sequencing. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2017, 8: 2148. DOI:10.3389/fmicb.2017.02148 |

| [16] | Caporaso JG, Kuczynski J, Stombaugh J, Bittinger K, Bushman FD, Costello EK, Fierer N, Pe?a AG, Goodrich JK, Gordon JI, Huttley GA, Kelley ST, Knights D, Koenig JE, Ley RE, Lozupone CA, McDonald D, Muegge BD, Pirrung M, Reeder J, Sevinsky JR, Turnbaugh PJ, Walters WA, Widmann J, Widmann T, Zaneveld J, Zaneveld R. QIIME allows analysis of high-throughput community sequencing data. Nature Methods, 2010, 7(5): 335-336. DOI:10.1038/nmeth.f.303 |

| [17] | Callahan BJ, McMurdie PJ, Rosen MJ, Han AW, Johnson AJA, Holmes SP. DADA2:High-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nature Methods, 2016, 13(7): 581-583. DOI:10.1038/nmeth.3869 |

| [18] | Barberán A, Bates ST, Casamayor EO, Fierer N. Using network analysis to explore co-occurrence patterns in soil microbial communities. The ISME Journal, 2012, 6(2): 343-351. DOI:10.1038/ismej.2011.119 |

| [19] | Mukaka MM. Statistics corner:A guide to appropriate use of correlation coefficient in medical research. Malawi Medical Journal, 2012, 24(3): 69-71. |

| [20] | Cai LZ, Li HM, Zou CZ. Species composition and seasonal variation of marine nematodes on Futian mudflat in Shenzhen estuary. Chinese Biodiversity, 1999, 8(4): 385-390. (in Chinese) 蔡立哲, 厉红梅, 邹朝中. 深圳河口福田泥滩海洋线虫的种类组成及季节变化. 生物多样性, 1999, 8(4): 385-390. |

| [21] | Brannock PM, Waits DS, Sharma J, Halanych KM. High-throughput sequencing characterizes intertidal meiofaunal communities in northern gulf of Mexico (Dauphin Island and Mobile Bay, Alabama). The Biological Bulletin, 2014, 227(2): 161-174. DOI:10.1086/BBLv227n2p161 |

| [22] | Tang CQ, Leasi F, Obertegger U, Kieneke A, Barraclough TG, Fontaneto D. The widely used small subunit 18S rDNA molecule greatly underestimates true diversity in biodiversity surveys of the meiofauna. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2012, 109(40): 16208-16212. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1209160109 |

| [23] | Lloyd KG, Schreiber L, Petersen DG, Kjeldsen KU, Lever MA, Steen AD, Stepanauskas R, Richter M, Kleindienst S, Lenk S, Schramm A, J?rgensen BB. Predominant archaea in marine sediments degrade detrital proteins. Nature, 2013, 496(7444): 215-218. DOI:10.1038/nature12033 |

| [24] | Lazar CS, Baker BJ, Seitz KW, Teske AP. Genomic reconstruction of multiple lineages of uncultured benthic archaea suggests distinct biogeochemical roles and ecological niches. The ISME Journal, 2017, 11(5): 1118-1129. DOI:10.1038/ismej.2016.189 |

| [25] | Meng J, Xu J, Qin D, He Y, Xiao X, Wang FP. Genetic and functional properties of uncultivated MCG archaea assessed by metagenome and gene expression analyses. The ISME Journal, 2014, 8(3): 650-659. DOI:10.1038/ismej.2013.174 |

| [26] | Chen YL, Pan J, Zhou ZC, Wang FP, Li M. Progress in studies on Bathyarchaeota in coastal ecosystems. Microbiology China, 2017, 44(7): 1690-1698. (in Chinese) 陈玉连, 潘杰, 周之超, 王风平, 李猛. 滨海深古菌的研究进展. 微生物学通报, 2017, 44(7): 1690-1698. |

| [27] | Mu?mann M, Pjevac P, Krüger K, Dyksma S. Genomic repertoire of the Woeseiaceae/JTB255, cosmopolitan and abundant core members of microbial communities in marine sediments. The ISME Journal, 2017, 11(5): 1276-1281. DOI:10.1038/ismej.2016.185 |

| [28] | Chen GJ, Wang ZJ, Du ZJ, Zhao JX. Woeseia oceani gen. nov., sp. nov., a chemoheterotrophic member of the order Chromatiales, and proposal of Woeseiaceae fam. nov.. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2016, 66(1): 107-112. DOI:10.1099/ijsem.0.000683 |

| [29] | Proctor LM. Nitrogen-fixing, photosynthetic, anaerobic bacteria associated with pelagic copepods. Aquatic Microbial Ecology, 1997, 12(2): 105-113. |

| [30] | Llorens-Marès T, Yooseph S, Goll J, Hoffman J, Vila-Costa M, Borrego CM, Dupont CL, Casamayor EO. Connecting biodiversity and potential functional role in modern euxinic environments by microbial metagenomics. The ISME Journal, 2015, 9(7): 1648-1661. DOI:10.1038/ismej.2014.254 |

| [31] | Bazylinski DA, Morillo V, Lefèvre CT, Viloria N, Dubbels BL, Williams TJ. Endothiovibrio diazotrophicus gen. nov., sp. nov., a novel nitrogen-fixing, sulfur-oxidizing gammaproteobacterium isolated from a salt marsh. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology, 2017, 67(5): 1491-1498. DOI:10.1099/ijsem.0.001743 |

| [32] | Ferris H, Venette RC, van der Meulen HR, Lau SS. Nitrogen mineralization by bacterial-feeding nematodes:verification and measurement. Plant and Soil, 1998, 203(2): 159-171. DOI:10.1023/A:1004318318307 |

| [33] | Ferris H, Venette RC, Lau SS. Population energetics of bacterial-feeding nematodes:Carbon and nitrogen budgets. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 1997, 29(8): 1183-1194. DOI:10.1016/S0038-0717(97)00035-7 |

| [34] | Postma-Blaauw MB, de Vries FT, de Goede RGM, Bloem J, Faber JH, Brussaard L. Within-trophic group interactions of bacterivorous nematode species and their effects on the bacterial community and nitrogen mineralization. Oecologia, 2005, 142(3): 428-439. DOI:10.1007/s00442-004-1741-x |

| [35] | Gebremikael MT, Steel H, Bert W, Maenhout P, Sleutel S, de Neve S. Quantifying the contribution of entire free-living nematode communities to carbon mineralization under contrasting C and N availability. PLoS One, 2015, 10(9): e0136244. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0136244 |

| [36] | N?slund J, Nascimento FJA, Gunnarsson JS. Meiofauna reduces bacterial mineralization of naphthalene in marine sediment. The ISME Journal, 2010, 4(11): 1421-1430. DOI:10.1038/ismej.2010.63 |