)

) 1浙江大学管理学院, 杭州 310058

2中国农业大学经济管理学院, 北京 100083

3北京大学光华管理学院, 北京 100871

收稿日期:2017-09-20出版日期:2018-10-15发布日期:2018-08-23基金资助:* 国家自然科学基金项目资助(71632002)Self-monitoring in group context: Its indirect benefits for individual status attainment and group task performance

HU Qiongjing1, LU Xi2, ZHANG Zhixue3( )

) 1 School of Management, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou 310058, China

2 College of Economics and Management, China Agricultural University, Beijing 100083, China

3 Guanghua School of Management, Peking University, Beijing 100871, China

Received:2017-09-20Online:2018-10-15Published:2018-08-23摘要/Abstract

摘要: 自我监控是与人际互动密切相关的人格特质。在群体建立和发展的过程中, 自我监控不仅影响个体的人际交往质量, 同时也作用于群体内部的互动; 并且, 自我监控的作用可能随着群体的发展而发生动态变化。为探究上述设想, 本研究针对32个大学新生寝室进行了一学期的跟踪调查。结果表明, 在个体层面, 个体自我监控水平促进群体成员对该个体的积极情感, 并进而间接促进其在群体中的地位获取(个体地位和友谊网络中心度); 在群体层面, 群体自我监控水平促进群体成员间的凝聚力, 并进而间接促进群体在合作中的绩效表现。此外, 个体自我监控水平对他人积极情感的影响存在时间效应, 具体而言, 其正向效应随着群体发展得到一定程度的增强。本研究揭示了自我监控对于个体和群体发生影响的机理, 对于自我监控理论以及地位等相关领域做出了一定的贡献。

图/表 7

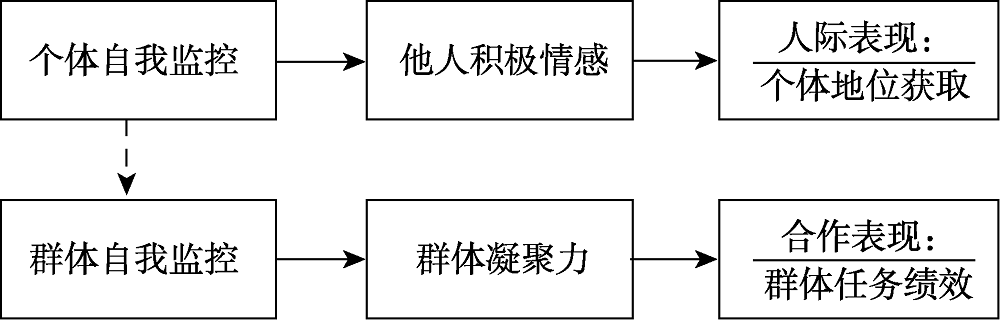

图1自我监控作用的机理与影响图示 注:实线箭头表示概念间的因果关系; 虚线箭头表示群体概念由个体概念加成得到

图1自我监控作用的机理与影响图示 注:实线箭头表示概念间的因果关系; 虚线箭头表示群体概念由个体概念加成得到

图1自我监控作用的机理与影响图示 注:实线箭头表示概念间的因果关系; 虚线箭头表示群体概念由个体概念加成得到

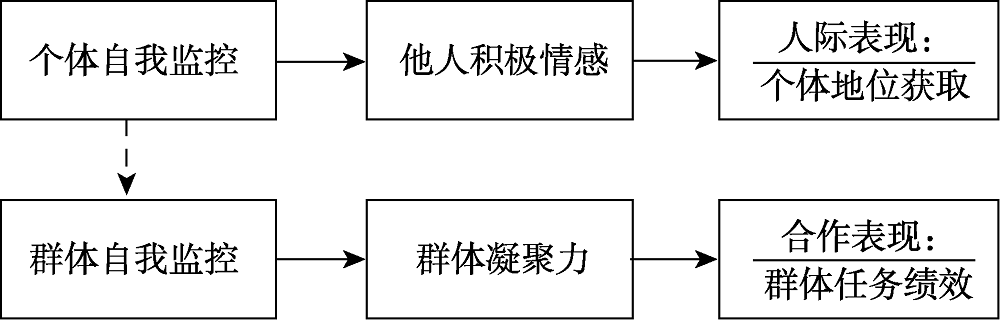

图2他人积极情感测量示例①(1 感谢匿名评审专家建议我们采用示意图的方式来更清晰地表现测量方式。)

图2他人积极情感测量示例①(1 感谢匿名评审专家建议我们采用示意图的方式来更清晰地表现测量方式。)

图2他人积极情感测量示例①(1 感谢匿名评审专家建议我们采用示意图的方式来更清晰地表现测量方式。)表1个体层面变量均值、标准差和相关系数

| 变量 | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. 个体自我监控(T1) | 4.69 | 0.67 | ||||

| 2. 他人积极情感(T2) | 4.84 | 0.92 | 0.18* | |||

| 3. 他人积极情感(T3) | 4.90 | 0.92 | 0.31*** | 0.64*** | ||

| 4. 个体地位(T3) | 5.08 | 0.98 | 0.04 | 0.41*** | 0.62*** | |

| 5. 友谊网络中心度 (T3) | 0.78 | 0.34 | 0.01 | 0.28** | 0.32*** | 0.29** |

表1个体层面变量均值、标准差和相关系数

| 变量 | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. 个体自我监控(T1) | 4.69 | 0.67 | ||||

| 2. 他人积极情感(T2) | 4.84 | 0.92 | 0.18* | |||

| 3. 他人积极情感(T3) | 4.90 | 0.92 | 0.31*** | 0.64*** | ||

| 4. 个体地位(T3) | 5.08 | 0.98 | 0.04 | 0.41*** | 0.62*** | |

| 5. 友谊网络中心度 (T3) | 0.78 | 0.34 | 0.01 | 0.28** | 0.32*** | 0.29** |

表2群体层面变量均值、标准差和相关系数

| 变量 | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. 群体自我监控 (T1) | 4.69 | 0.30 | |||

| 2. 群体凝聚力(T2) | 5.49 | 0.91 | 0.49** | ||

| 3. 群体凝聚力(T3) | 5.54 | 0.91 | 0.45* | 0.60*** | |

| 4. 群体任务绩效 (T3) | 11.64 | 3.91 | 0.28 | 0.45** | 0.45** |

表2群体层面变量均值、标准差和相关系数

| 变量 | M | SD | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. 群体自我监控 (T1) | 4.69 | 0.30 | |||

| 2. 群体凝聚力(T2) | 5.49 | 0.91 | 0.49** | ||

| 3. 群体凝聚力(T3) | 5.54 | 0.91 | 0.45* | 0.60*** | |

| 4. 群体任务绩效 (T3) | 11.64 | 3.91 | 0.28 | 0.45** | 0.45** |

表3个体层面的跨层次回归分析结果

| 变量 | 模型1 他人积极 情感(T2) | 模型2 他人积极 情感(T3) | 模型3 个人地位(T3) | 模型4 友谊网络 中心度(T3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 个体自我监控 | 0.25* (0.12) | 0.60*** (0.07) | -0.08 (0.12) | -0.03 (0.04) |

| 他人积极情感(T2) | 0.28** (0.09) | 0.42*** (0.09) | 0.10** (0.03) | |

| 样本量(群体水平) | 32 | 32 | 32 | 32 |

| 样本量(个体水平) | 122 | 122 | 122 | 122 |

| 偏差(deviance) | 319.93* | 250.27*** | 311.67*** | 64.40** |

表3个体层面的跨层次回归分析结果

| 变量 | 模型1 他人积极 情感(T2) | 模型2 他人积极 情感(T3) | 模型3 个人地位(T3) | 模型4 友谊网络 中心度(T3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 个体自我监控 | 0.25* (0.12) | 0.60*** (0.07) | -0.08 (0.12) | -0.03 (0.04) |

| 他人积极情感(T2) | 0.28** (0.09) | 0.42*** (0.09) | 0.10** (0.03) | |

| 样本量(群体水平) | 32 | 32 | 32 | 32 |

| 样本量(个体水平) | 122 | 122 | 122 | 122 |

| 偏差(deviance) | 319.93* | 250.27*** | 311.67*** | 64.40** |

表4群体层面一般线性回归分析结果

| 变量 | 模型1 群体凝聚力 (T2) | 模型2 群体凝聚力 (T3) | 模型3 群体任务绩效 (T3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 群体自我监控 | 1.47** (0.48) | 0.62 (0.50) | 0.47 (1.22) |

| 群体凝聚力(T2) | 0.49** (0.17) | 0.89* (0.40) | |

| 样本量 | 32 | 32 | 32 |

| R2 | 0.24 | 0.39 | 0.21 |

| F | 9.22** | 9.13*** | 3.83* |

表4群体层面一般线性回归分析结果

| 变量 | 模型1 群体凝聚力 (T2) | 模型2 群体凝聚力 (T3) | 模型3 群体任务绩效 (T3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 群体自我监控 | 1.47** (0.48) | 0.62 (0.50) | 0.47 (1.22) |

| 群体凝聚力(T2) | 0.49** (0.17) | 0.89* (0.40) | |

| 样本量 | 32 | 32 | 32 |

| R2 | 0.24 | 0.39 | 0.21 |

| F | 9.22** | 9.13*** | 3.83* |

表5RMediation检验间接效应的结果

| 路径 | 自变量→ 中介变量(a) | 中介变量→ 因变量(b) | 估计量(a × b) | 偏差校正的 置信区间 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 个体自我监控(T1)-他人积极情感(T2)-个体地位(T3) | 0.25 | 0.42 | 0.105 | [0.006, 0.225] |

| 个体自我监控(T1)-他人积极情感(T2)-友谊网络中心度(T3) | 0.25 | 0.10 | 0.025 | [0.001, 0.058] |

| 群体自我监控(T1)-群体凝聚力(T2)-群体任务绩效(T3) | 1.47 | 0.89 | 1.308 | [0.105, 3.012] |

表5RMediation检验间接效应的结果

| 路径 | 自变量→ 中介变量(a) | 中介变量→ 因变量(b) | 估计量(a × b) | 偏差校正的 置信区间 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 个体自我监控(T1)-他人积极情感(T2)-个体地位(T3) | 0.25 | 0.42 | 0.105 | [0.006, 0.225] |

| 个体自我监控(T1)-他人积极情感(T2)-友谊网络中心度(T3) | 0.25 | 0.10 | 0.025 | [0.001, 0.058] |

| 群体自我监控(T1)-群体凝聚力(T2)-群体任务绩效(T3) | 1.47 | 0.89 | 1.308 | [0.105, 3.012] |

参考文献 57

| [1] | Anderson C., John O. P., Keltner D., & Kring A. M . ( 2001). Who attains social status? Effects of personality and physical attractiveness in social groups. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81( 1), 116-132. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.81.1.116URLpmid: 11474718 |

| [2] | Bai F . ( 2017). Beyond dominance and competence: A moral virtue theory of status attainment. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 21( 3), 203-227. doi: 10.1177/1088868316649297URLpmid: 27225037 |

| [3] | Baldwin T. T., Bedell M. D., & Johnson J. L . ( 1997). The social fabric of a team-based M.B.A. program: Network effects on student satisfaction and performance. Academy of Management Journal, 40( 6), 1369-1397. |

| [4] | Beal D. J., Cohen R. R., Burke M. J., & McLendon C. L . ( 2003). Cohesion and performance in groups: A meta-analytic clarification of construct relations. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88( 6), 989-1004. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.88.6.989URLpmid: 14640811 |

| [5] | Bell S.T . ( 2007). Deep-level composition variables as predictors of team performance: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology,92( 3), 595-615. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.92.3.595URLpmid: 17484544 |

| [6] | Bendersky C., &Shah N.P . ( 2012). The cost of status enhancement: Performance effects of individuals’ status mobility in task groups. Organization Science, 23( 2), 308-322. doi: 10.1287/orsc.1100.0543URL |

| [7] | Bradley B. H., Klotz A. C., Postlethwaite B. E., & Brown K. G . ( 2013). Ready to rumble: How team personality composition and task conflict interact to improve performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 98( 2), 385-392. doi: 10.1037/a0029845URL |

| [8] | Colbert A. E., Barrick M. R., & Bradley B. H . ( 2014). Personality and leadership composition in top management teams: Implications for organizational effectiveness. Personnel Psychology, 67( 2), 351-387. doi: 10.1111/peps.2014.67.issue-2URL |

| [9] | Correl S.J., &Ridgeway C.L . ( 2003). Expectation states theory. In Delamater, J.(Ed.), Handbook of Social Psychology |

| [10] | Dabbs J. M., Evans M. S., Hopper C. H., & Purvis J. A . ( 1980). Self-monitors in conversation: What do they monitor? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39( 2), 278-284. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.39.2.278URL |

| [11] | Day D. V., Schleicher D. J., Unckless A. L., & Hiller N. J . ( 2002). Self-monitoring personality at work: A meta- analytic investigation of construct validity. Journal of Applied Psychology, 87( 2), 390-401. doi: 10.1037//0021-9010.87.2.390URLpmid: 12002965 |

| [12] | Devine D.J., &Philips J.L . ( 2000). Do smarter teams do better? A meta-analysis of team level cognitive ability and team performance. Paper presented at the 15th annual conference of the Society for Industrial and Organizational Psychology, New Orleans,LA. |

| [13] | Diefendorff J. M., Croyle M. H., & Gosserand R. H . ( 2005). The dimensionality and antecedents of emotional labor strategies. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 66( 2), 339-357. doi: 10.1016/j.jvb.2004.02.001URL |

| [14] | Filho E., Dobersek U., Gershgoren L., Becker B., & Tenenbaum G . ( 2014). The cohesion-performance relationship in sport: A 10-year retrospective meta-analysis. Sport Science for Health, 10( 3), 165-177. doi: 10.1007/s11332-014-0188-7URL |

| [15] | Flynn F. J., Reagans R. E., Amanatullah E. T., & Ames D. R . ( 2006). Helping one’s way to the top: Self-monitors achieve status by helping others and knowing who helps whom. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 91( 6), 1123-1137. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.91.6.1123URL |

| [16] | Fredrickson B.L . ( 1998). What good are positive emotions? Review of General Psychology,2( 3), 300-319. doi: 10.1037/1089-2680.2.3.300URLpmid: 3156001 |

| [17] | Frey M.C., &Detterman D.K . ( 2004). Scholastic assessment or g? The relationship between the scholastic assessment test and general cognitive ability. Psychological Science, 15( 6), 373-378. |

| [18] | Frijda N. H. ( 1994). Varieties of affect: Emotions and episodes, moods, and sentiments. In Ekman, P., & Davidson, R. J. (Eds.), The nature of emotion: Fundamental questions (pp. 59-67). New York: Oxford University Press. |

| [19] | Gangestad S.W., & Snyder M . ( 2000). Self-monitoring: Appraisal and reappraisal. Psychological Bulletin, 126( 4), 530-555. |

| [20] | Hall R. J., Workman J. W., & Marchioro C. A . ( 1998). Sex, task, and behavioral flexibility effects on leadership perceptions. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 74( 1), 1-32. |

| [21] | Hobfoll S.E . ( 1989). Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist, 44( 3), 513-524. |

| [22] | Ickes W., Holloway R., Stinson L. L., & Hoodenpyle T. G . ( 2006). Self-monitoring in social interaction: The centrality of self-Affect. Journal of Personality, 74( 3), 659-684. |

| [23] | James L.R .( 1982). Aggregation bias in estimates of perceptual agreement. Journal of Applied Psychology, 67( 2), 219-229. |

| [24] | Jehn K.A., &Mannix E.A .( 2001). The dynamic nature of conflict: A longitudinal study of intragroup conflict and group performance. Academy of Management Journal, 44( 2), 238-251. |

| [25] | Jenkins J.M .( 1993). Self-monitoring and turnover - the impact of personality on intent to leave. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 14( 1), 83-91. |

| [26] | Kelly J.R., &Barsade S.G . ( 2001). Mood and emotions in small groups and work teams. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 86( 1), 99-130. |

| [27] | Klein H.J., , &Mulvey P.W . ( 1995). Two investigations of the relationships among group goals, goal commitment, cohesion, and performance. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 61( 1), 44-53. |

| [28] | Klein K. J., Lim B.-C., Saltz J. L., & Mayer D. M . ( 2004). How do they get there? An examination of the antecedents of centrality in team networks. Academy of Management Journal, 47( 6), 952-963. |

| [29] | LeBreton J.M., &Senter J.L . ( 2008). Answers to 20 Questions about interrater reliability and interrater agreement. Organizational Research Methods, 11( 4), 815-852. |

| [30] | Lennox R.D., &Wolfe R.N . ( 1984). Revision of the self-monitoring scale. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 46( 6), 1349-1364. |

| [31] | LePine J.A . ( 2003). Team adaptation and postchange performance: Effects of team composition in terms of members’ cognitive ability and personality. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88( 1), 27-39. |

| [32] | LePine J. A., Hollenbeck J. R., Ilgen D. R., & Hedlund J . ( 1997). Effects of individual differences on the performance of hierarchical decision-making teams: Much more than g. Journal of Applied Psychology,82( 5), 803-811. |

| [33] | Lin H.-C., & Rababah N .( 2014). CEO-TMT exchange, TMT personality composition, and decision quality: The mediating role of TMT psychological empowerment . Leadership Quarterly, 25( 5), 943-957. |

| [34] | Liu X., &Zhang Z ( 2005). Process of interaction among members in simulated work teams. Acta Psychological Sinica, 37( 2), 253-259. |

| [ 刘雪峰, 张志学 . ( 2005). 模拟情境中工作团队成员互动过程的初步研究及其测量. 心理学报, 37( 2), 253-259.] | |

| [35] | MacKinnon D. P., Fritz M. S., Williams J., & Lockwood C. M . ( 2007). Distribution of the product confidence limits for the indirect effect: Program PRODCLIN. Behavior Research Methods, 39( 3), 384-389. |

| [36] | MacKinnon D. P., Lockwood C. M., & Williams J . ( 2004). Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product and resampling methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 39( 1), 99-128. |

| [37] | Magee J.C., &Galinsky A.D .( 2008). Social hierarchy: The self-reinforcing nature of power and status. The Academy of Management Annals, 2( 1), 351-398. |

| [38] | Man D.C., &Lam S. S.K . ( 2003). The effects of job complexity and autonomy on cohesiveness in collectivistic and individualistic work groups: A cross-cultural analysis. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 24( 8), 979-1001. |

| [39] | Mehra A., Kilduff M., & Brass D. J . ( 2001). The social networks of high and low self-monitors: Implications for workplace performance. Administrative Science Quarterly, 46( 1), 121-146. |

| [40] | Mullen B., & Copper C .( 1994). The relation between group cohesiveness and performance: An integration. Psychological Bulletin, 115( 2), 210-227. |

| [41] | Norris S.L., &Zweigenhaft R.L . ( 1999). Self-monitoring, trust, and commitment in romantic relationships. The Journal of Social Psychology, 139( 2), 215-220. |

| [42] | Oh H., &Kilduff M .( 2008). The ripple effect of personality on social structure: Self-monitoring origins of network brokerage. Journal of Applied Psychology, 93( 5), 1155-1164. |

| [43] | Pettit N. C., Yong K., & Spataro S. E . ( 2010). Holding your place: Reactions to the prospect of status gains and losses. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 46( 2), 396-401. |

| [44] | Roberson Q.M., &Williamson I.O .( 2012). Justice in self-monitoring teams: The role of social networks in the emergence of procedural justice climates. Academy of Management Journal,55( 3), 685-701. |

| [45] | Scott B. A., Barnes C. M., & Wagner D. T . ( 2012). Chameleonic or consistent? A multilevel investigation of emotional labor variability and self-monitoring. Academy of Management Journal, 55( 4), 905-1050. |

| [46] | Scott B. A., Colquitt J. A., & Zapata-Phelan C. P . ( 2007). Justice as a dependent variable: subordinate charisma as a predictor of interpersonal and informational justice perceptions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92( 6), 1597-1609. |

| [47] | Synder M .( 1974). Self-monitoring of expressive behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 30( 4), 526-537. |

| [48] | Synder M., & Cantor N . ( 1980). Thinking about ourselves and others: Self-monitoring and social knowledge. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39( 2), 222-234. |

| [49] | Tofighi D., & MacKinnon D.P . ( 2011). RMediation: An R package for mediation analysis confidence intervals. Behavior Research Methods, 43( 3), 692-700. |

| [50] | Tuckman B.W . ( 1965). Developmental sequence in small groups. Psychological Bulletin, 63( 6), 384-399. |

| [51] | Turner R.G . ( 1980). Self-monitoring and humor production. Journal of Personality, 48( 2), 163-167. |

| [52] | Turnley W.H., &Bolino M.C . ( 2001). Achieving desired images while avoiding undesired image: Exploring the role of self-monitoring in impression management. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86( 2), 351-360. |

| [53] | Tziner A., &Eden D . ( 1985). Effects of crew composition on crew performance: Does the whole equal the sum of its parts? Journal of Applied Psychology, 70( 1), 85-93. |

| [54] | Wang S., Hu Q., & Dong B . ( 2015). Managing personal networks: An examination of how high self-monitors achieve better job performance. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 91, 180-188. |

| [55] | Watson D . ( 2000). Mood and temperament. New York: Guilford Press. |

| [56] | Watson D., & Clark L.A .( 1994). The PANAS-X: Manual for the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule, expanded form. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press |

| [57] | Zaccaro S. J., Foti R. J., & Kenny D. A . ( 1991). Self-monitoring and trait-based variance in leadership: An investigation of leader flexibility across multiple group situations. Journal of Applied Psychology, 76( 2), 308-315. |

相关文章 10

| [1] | 张景焕, 付萌萌, 辛于雯, 陈佩佩, 沙莎. 小学高年级学生创造力的发展:性别差异及学校支持的作用[J]. 心理学报, 2020, 52(9): 1057-1070. |

| [2] | 陈红君,赵英,伍新春,孙鹏,谢瑞波,冯杰. 小学儿童词汇知识与阅读理解的关系:交叉滞后研究[J]. 心理学报, 2019, 51(8): 924-934. |

| [3] | 郭海英;陈丽华; 叶枝;潘瑾;林丹华. 流动儿童同伴侵害的特点及与内化问题的循环作用关系:一项追踪研究[J]. 心理学报, 2017, 49(3): 336-348. |

| [4] | 周宵, 伍新春, 王文超, 田雨馨. 社会支持、创伤后应激障碍与创伤后成长之间的关系:来自雅安地震后小学生的追踪研究[J]. 心理学报, 2017, 49(11): 1428-1438. |

| [5] | 赵英;程亚华;伍新春;阮氏芳. 汉语儿童语素意识与词汇知识的双向关系:一项追踪研究[J]. 心理学报, 2016, 48(11): 1434-1444. |

| [6] | 梁宗保;张光珍;邓慧华;宋媛;郑文明. 学前儿童努力控制的发展轨迹与父母养育的关系:一项多水平分析[J]. 心理学报, 2013, 45(5): 556-567. |

| [7] | 范方,耿富磊,张岚,朱清. 负性生活事件、社会支持和创伤后应激障碍症状:对汶川地震后青少年的追踪研究[J]. 心理学报, 2011, 43(12): 1398-1407. |

| [8] | 胡金生,杨丽珠. 高低自我监控者在不同互动情境中的被洞悉错觉[J]. 心理学报, 2009, 41(01): 79-85. |

| [9] | 宋广文,陈启山. 印象整饰对强迫服从后态度改变的影响[J]. 心理学报, 2003, 35(03): 397-403. |

| [10] | 李峰,张德,张宇莲. 心理控制源与自我监控在预测中的交互作用[J]. 心理学报, 1992, 24(3): 39-44. |

PDF全文下载地址:

http://journal.psych.ac.cn/xlxb/CN/article/downloadArticleFile.do?attachType=PDF&id=4284