, 刘春卉

, 刘春卉 , 汪毅

, 汪毅Rent gap and gentrification in the inner city of Nanjing

SONGWeixuan , LIUChunhui

, LIUChunhui , WANGYi

, WANGYi通讯作者:

收稿日期:2016-11-20

修回日期:2017-07-25

网络出版日期:2017-12-25

版权声明:2017《地理学报》编辑部本文是开放获取期刊文献,在以下情况下可以自由使用:学术研究、学术交流、科研教学等,但不允许用于商业目的.

基金资助:

作者简介:

-->

展开

摘要

关键词:

Abstract

Keywords:

-->0

PDF (4797KB)元数据多维度评价相关文章收藏文章

本文引用格式导出EndNoteRisBibtex收藏本文-->

1 引言

中产阶层化(Gentrification)是一种城市居住空间的重构、分异与隔离现象;是指具有更高社会经济地位的土地使用者置换原使用者,并伴随固定资产再投资导致的建成环境改变过程[1]。历经半个世纪的发展演化,中产阶层化愈发呈现出复杂性与多样化的特点[2-3]:一是内涵不断延伸,由“内城区中产阶层置换工人阶层现象”[4]拓展为不同区域不同阶层的高级化重构过程[5];二是区域间呈现异质化,南北半球间[6]、不同国家间[7]、相同国家不同城市间[8],甚至相同城市不同地区间[9],都可能存在中产阶层化现象和机理的巨大差异;三是内部类型不断分化,由古典中产阶层化(classic gentrification)[10]衍生出乡村中产阶层化(rural gentrification)[11]、超级中产阶层化(super-gentrification)[12]、郊区中产阶层化(suburban gentrification)[13]、学生中产阶层化(studentification)[14]、新建中产阶层化(new-build gentrification)[15],以及近年来出现的贫民区中产阶层化(slum gentrification)[16]、混合中产阶层化(hybrid gentrification)[17]、学区中产阶层化(jiaoyufication)[18-19]等形式。进入21世纪,中产阶层化已经发展为一种全球化现象(planetary gentrification)[20],以不同形式出现在各国包括第三世界国家城市中[15],成为全球城市发展战略(global urban strategy)[21],甚至上升为一种“中产阶层化地理学”(geography of gentrification)[12, 16]。全球化和新自由主义背景下,中国以住房市场化改革和大规模城市更新为契机,城市中大量传统邻里被推倒重建为高档封闭社区(gated community),原住居民被更高收入的富裕群体和中产阶层取代,这一城市社会空间重构过程被认为是中国最典型的中产阶层化现象[20, 22]。转型期特有的政治经济环境下,中国城市中产阶层化具有相对独特的“中国面孔”:一是驱动模式由政府主导(state-led gentrification)[23];二是实现方式以拆旧建新为主[24];三是规模更大、速度更快、“破坏性”更强[20]。尽管中国与欧美城市典型中产阶层化存在一定差异,但实质上皆是住宅市场化和土地竞租原则下,资本流向潜在可增值区域,由此引发该区域建成环境和邻里阶层的高端化重构[25-27]。因此,本文利用“租差”这一西方解读中产阶层化的经典理论工具,结合中国实际开展理论嫁接与地方化融合创新,试图从“租差”视角揭示中国中产阶层化的内生机理,探讨中产阶层化对城市社会空间重构的深远影响。

2 “租差”理论及其本土修正模型

2.1 “租差”理论对中产阶层化的解释

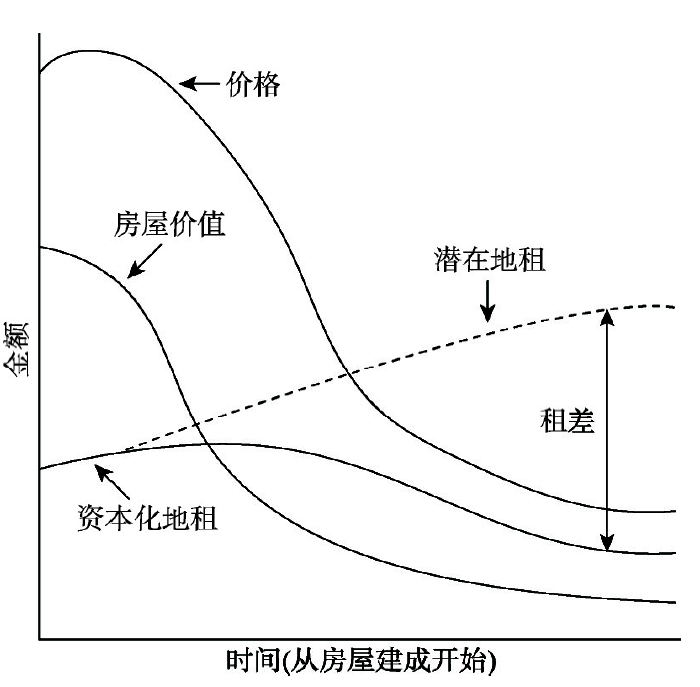

在Glass等****的早期研究中,中产阶层化被理解为“新中产阶层”取代工人阶层的“重返城市”运动,“中产群体及其选择”曾长期占据着欧美中产阶层化研究的核心[5]。与此不同,以Smith等为代表的新马克思主义****,从城市经济重构角度,强调资本和住宅供给在中产阶层化过程中的关键作用,认为中产阶层只是以消费者和参与者的身份存在,提出“是资本,而不是人”主导着中产阶层化进程[21]。Smith在其“非均衡发展”(uneven development)的基本理念之上,创造出作为“中产阶层化先决条件”的“租差”(rent gap)概念[28-29](图1)。 显示原图|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT

显示原图|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT图1Smith的住宅贬值周期和“租差”演变

注:根据Smith[

-->Fig. 1Residential devaluation cycle and rent gap evolution of Smith

-->

“租差”是指“‘潜在地租’①(①潜在地租指土地在“最高且最佳”利用方式下能够实现的资本化总和。)与‘资本化地租’②(②资本化地租指当前土地利用条件下可以获得的实际资本总量。)之间的差额”[29]。地块开发之初,投资主体会尽可能采用能够实现当时土地潜在价值的方式进行土地开发与资本化,此时该地块的“资本化地租”等同于“潜在地租”;建筑物具有空间固着、独占、持久等不同于一般商品的特性,并会随时间折旧而相对贬值,即“资本化地租”在开发完成一定时间后将逐渐下降;与此同时,建筑物所占据土地的“潜在地租”会持续增加,这就形成了“潜在地租”与“资本化地租”间不断扩大的“租差”。“租差”象征着开发商再投资的收益预期,当“租差”扩大到足以支付城市更新所需各项成本,并将产生使所有投资者满意的丰厚利润时,资本就会重新流向老旧城区,推动中产阶层化现象的发生。

自“租差”概念在欧美国家出现以来,迅速成为全球中产阶层化研究中极具影响力和争议性的焦点话题。尽管“租差”理论因强调资本主导而缺乏对“人”的关注,饱受以Ley和Butler等后工业化文化分析阵营的批评[30-31],但毫无疑问,“租差”理论在全球新自由主义语境下,以土地和住房市场为观察视角,对中产阶层化的产生具有广泛与非凡的经济解释力[32]。虽然各国政治经济环境与城市发展模式有所差异,但城市土地与住房开发经营者的资本利益取向是大致相同的,即尽可能以最低价购买土地和住宅,然后以最高的价格出售。不过,在运用“租差”理论解释不同国家地方化实践时,需要结合各国特定的制度环境与城市化阶段,通过检验、扩展和修正Smith的“租差”理论模型,重点从分析“租差”在何时、何地以及如何产生等问题着手,演绎出符合本国实际情况的“租差”及中产阶层化分析框架。

2.2 “租差”在中国中产阶层化研究中的适应性

古典“租差”概念是Smith在研究欧美资本主义城市中产阶层化过程中,解析资本为何重返城市中心时发明的,其理论内涵不能完全契合中国的实际情况,具体表现为 两点:①“租差”理论是基于西方完全市场经济和土地私有制前提假设,用以解释市场主导型中产阶层化的发生机制。但诚如Lees等所言[20],并非所有国家的中产阶层化案例都可以界定为新自由主义的,特别是东亚等集权型国家。就中国而言,城市土地所有权归属国家或集体,并可能与土地使用权、收益权和处分权等土地权利分属不同主体,这一明显异于西方语境的前设条件,既造就了中国特色的“政府主导型中产阶层化” [33],也使“租差”在中国的实践更趋复杂。②“租差”理论的适用范围限定为欧美城市郊区化浪潮和内城衰败发生后,工人阶层居住的邻里被中产阶层购房者、土地所有者和开发商所修缮复兴的过程,修缮后的区域在开发密度和建筑类型上与初始状态基本保持一致。不同于西方修缮和改造破败住宅和街区,中国中产阶层化过程多数以拆旧建新的空间再开发形式实现[34],涉及到地上建筑价值的灭失和再现,以及价值、价格、地租等不同价值形式及其转换问题[35]。利用古典“租差”模型解释这种“大规模拆毁与置换”[36]的“新建中产阶层化”过程存在一定困难。由于土地等制度环境和中产阶层化实现方式的差异,Smith的“租差”模型难以准确拟合中国城市中产阶层化“空间再生产”后“潜在地租”与“资本化地租”的演变轨迹。例如在Smith的模型中,住房建成后随着建筑老化和维修成本上升,其“资本化地租”和住宅“价格”都将持续降低(图1);而中国的实际情况是,自20世纪末住房市场化改革以来,城市“地租”与住宅“价格”一直快速波动上涨,即便是内城传统住宅,也不过是在价值增速上低于新建住宅,尚未出现“资本化地租”或“价格”持续下跌的局面。然而,并不能因此否定“租差”理论在中国的适用性或轻言“中国例外论”[37]。因为在分权化、市场化、全球化语境下[38],中国“政府企业化”转型和“城市增长联盟”崛起,以及金融资本主义席卷全球和新自由主义向第三世界国家“政策转移”,使中国城市“空间再生产”出现与西方类似的资本逐利逻辑。政治经济管制环境转变与城市空间转型重构背景下,土地所有者、投资者和开发经营主体等通过扩大“资本化地租”以追求“超额利润”,同样是中国中产阶层化的重要价值取向与驱动机制。

2.3 中国政治经济转型下“租差”的实现与扩大

随着社会主义福利体制瓦解,城市土地使用制度由“无偿划拨”转向“有偿使用”,城市住房由“福利”变为“商品”;于是土地成为城市政府可资经营的、最大活化国有资产[39],城市空间成为投资者实现资本增殖的垄断性工具。相应地,城市土地及住房的交换价值经历以下阶段逐步得到体现:(1)地租隐藏阶段(1988年以前)。在新中国成立后较长一段时期内,国家政府控制着城市土地供给、住房分配甚至人口流动,城市土地和居民住房因无法自由交易而单纯具有使用价值,交换价值即“资本化地租”被隐藏。

(2)租差显露阶段(20世纪末)。1988年开始实施的城市土地有偿使用制度和1998年全国范围内正式取消福利分房,使城市土地与住房的市场价值被激活,特别是城市中心等优质区位,“资本化地租”与“潜在地租”间出现巨大“租差”。

(3)地租跃升阶段(21世纪以来)。2000年以来大量资金进入城市房地产市场,推动城市地价和房价加速上涨。权力与资本“合谋”及土地竞租模式下,城市“地王”、“楼王”不断出现,推高区域房地产价格和城市整体“资本化地租”。虽然“潜在地租”也随城市发展而上升,但远不及地价和房价的上涨速度,导致“租差”随时间推移(建筑老化)不增反降,直至市场价格(资本化地租)最终高于并偏离实际价值(潜在地租)。

根据Smith的“租差”理论,在“租差”缩小的情况下,城市旧城更新会因资本无利可图而趋于停止,资本将转向回报率更高的城市外围未开发地区。而事实是,中国城市郊区化与城市内部更新基本上是同时发生的,城市旧城区从未出现衰败迹象,反而因新建筑、新功能、新阶层的不断汇聚而一直保持着“寸土寸金”的旺盛活力。究其原因,中国地方政府在城市空间再生产中扩大“租差”的努力,无疑发挥着关键作用。

在住房拆迁与新建过程中,城市政府作为中央政府的“代理人”,一方面根据国家相关要求制定房屋拆迁补偿标准,合法降低支付给原土地使用者的“资本化地租”,即通过行政手段强制性扩大“租差”,或称“实际租差”(rent gap),并收回包括所有权、使用权、收益权和处分权在内的所有土地权利;另一方面,通过“招拍挂”等市场化土地批租方式,再将土地以接近或高于“潜在地租”的交易价格出让给房地产开发商,并极力保障房地产投资较高的资本回报率,形成预期中“资本化地租”将逐渐高于“潜在地租”的另一种“租差”形式,本文称其为“预期租差”(rent jump)。于是,地方政府获得可观的“土地财政”收入,房地产开发商和商品房消费者拥有资本增值的良好预期,加上金融部门在各个环节的推波助澜,所有投资主体都能够在城市更新再造过程中获得满意的回报。

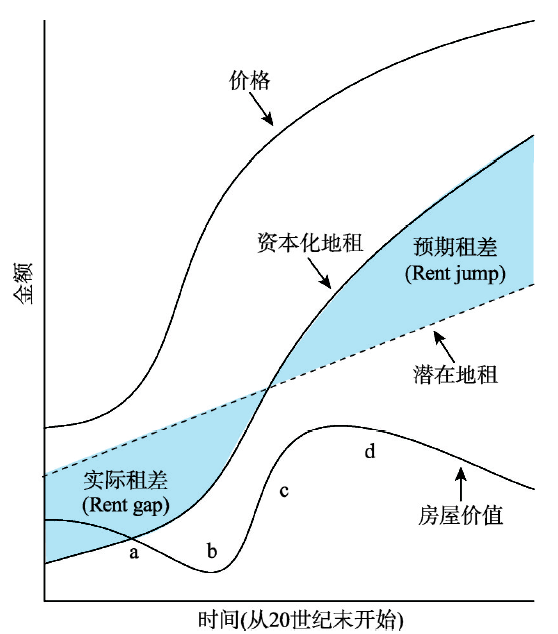

结合中国实际,修正后的“租差”模型如图2所示。与古典“租差”曲线的差异主要表现在:① 20世纪末,由于住房的福利属性,即使时间起点是新建住房,其“资本化地租”也要低于“潜在地租”;②“资本化地租”和住宅“价格”因市场化能量释放而快速上涨,并且至今保持上涨趋势;③ 驱动中产阶层化的“租差”包括政府能够获取的“实际租差”和房地产投资者可获利的“预期租差”两部分。

显示原图|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT

显示原图|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT图2修正后的“租差”模型

注:土地权包括除土地所有权外的土地使用权、收益权和处分权:a-传统建筑老化阶段土地权属:原住居民;b-征地拆迁至土地出让阶段土地权属:地方政府;c-商品住宅建设及销售阶段土地权属:房地产商;d-商品住宅使用阶段土地权属:购房者。

-->Fig. 2Corrected "rent gap" model

-->

3 南京内城中产阶层化现象

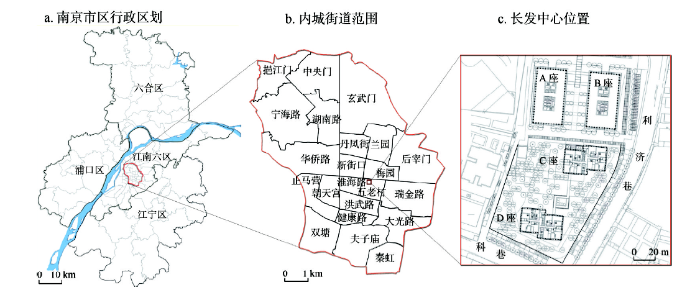

素有“六朝古都”之称的南京内城区,城墙围合面积约为40 km2,是南京城市核心区(图3)。本文选择南京内城为样本区域,主要是考虑:其一,南京是中国大城市的典型代表,更能代表中国中产阶层化的一般模式和共性规律;其二,内城是欧美中产阶层化的最典型发生地段,也是中国中产阶层化最早及最频繁发生区域,能够提供充足样本案例并便于进行国际比较;其三,南京内城土地全部国有,排除城市外围农村集体用地征地拆迁情况,可降低分析维度与复杂性。同时最新研究指出,刻画中国城市中产阶层化现象应从以下角度着手:一是资本逐利驱动的地租与“租差”变化;二是社区物质环境与社会构成向上跃升;三是邻里社会阶层变迁与低阶层被置换等[18-19]。因此,本文从上述三个方面,利用南京内城房屋拆迁及补偿、土地出让和利用方式转变、住宅价格变化等宏观数据,并通过揭示“利济巷地块”空间再生产为长发中心(CFC)的微观样本,分析南京内城中产阶层化现象以及“租差”在推动该过程所发挥的作用。 显示原图|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT

显示原图|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT图3南京市区行政区划、内城街道范围及长发中心位置

-->Fig. 3Administrative division of Nanjing, sub-district offices in inner city and location of CFC

-->

3.1 改革开放后城市空间“租差”的出现与资本化激活

1978年以前,在“先生产后生活”的城市发展方针下,城市建设资金匮乏,南京内城十分拥挤,一度居住着150万人口。改革开放以后,城市居住环境改善得到重视,如1978-1987年10年间,南京新建住宅面积超过建国后30年的总和[34]。随着1992年南京城市土地政策和住房制度改革,原本隐藏的土地价值和区位差异开始显露,持续扩大的“租差”为内城改造提供了强大动力。至20世纪末,南京内城中依然存在较大规模的棚户区、危旧房、老厂房和非法建筑亟待改造。21世纪伊始,南京城市政府出于增加税源、改善城市景观形象、疏散过度拥挤的人口等因素考虑,同时为满足城市产业转型发展和“新富裕阶层”[40]对现代居住条件的需求,开始推进大规模内城拆迁与重建[16]。根据南京市房管局、拆迁办、国土局提供资料显示,2001-2011年间,南京内城较大规模的国有土地拆迁、出让超过150幅地块;从时间上看,南京内城拆迁与出让地块数量呈现抛物线式的变化规律,约50%的拆迁和土地出让发生在2005-2007年期间(表1)。Tab. 1

表1

表12001-2011年南京内城历年拆迁和出让地块占比情况

Tab. 1Proportion of demolition and land transfer in the inner city of Nanjing during 2001-2011

| 年份 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 合计 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 拆迁项目比例(%) | 1.6 | 7.2 | 12.4 | 6.4 | 17.2 | 22.8 | 12.0 | 8.8 | 7.6 | 2.4 | 1.6 | 100 |

| 出让地块比例(%) | 7.1 | 12.7 | 9.9 | 7.0 | 19.7 | 15.5 | 15.5 | 5.6 | 2.8 | 1.4 | 2.8 | 100 |

新窗口打开

在房屋拆迁补偿方面,补偿金额根据被拆迁房屋的房地产市场评估单价和被拆迁房屋的建筑面积确定。拆迁补偿标准大体上根据住房新旧程度和当时周边同类房价进行综合评估折算,因土地的国有属性,政府主要补偿房屋现存价值而不是土地和区位“地租”价值,更不考虑房地产未来增值部分。因此,城市政府等拆迁方支付给被拆迁者的补偿款要远低于该土地和住房的实际价值。当拆迁完成,城市政府将该块土地使用权转移给房地产开发商时,则会以基本符合“潜在地租”的“地价”进行出让,此处的“实际租差”转变为地方政府的“土地财政”收益。例如2001-2011年期间,南京内城拆迁补偿金额为18.29亿元,同期土地出让价款高达113.8亿元,也就是说,被拆迁户所得补偿金额仅相当于土地出让金的约16%(表2),而排除补偿性、开发性和业务性成本,地方政府获取高额土地收益。

Tab. 2

表2

表22001-2011年南京内城拆迁补偿金额与土地出让价款

Tab. 2Compensation for demolition and land transfer price in the inner city of Nanjing during 2001-2011

| 年份 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 合计 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 拆迁补偿款(亿元) | 0.05 | 0.75 | 1.95 | 1.63 | 2.72 | 4.42 | 2.45 | 1.87 | 1.42 | 0.27 | 0.77 | 18.29 |

| 土地出让金(亿元) | 1.4 | 12.2 | 19.7 | 9.3 | 8.5 | 6.8 | 27.2 | 4.4 | 5.9 | 1.3 | 17.1 | 113.8 |

新窗口打开

在土地出让后的重建过程中,房地产开发商通过规划设计、建设施工、宣传销售等开发程序,实现居住空间再生产和“资本化地租”的跃升。以“利济巷地块”再开发为例(图4),地块紧临有“南京长安街”之称的中山东路,距离“南京总统府”仅200 m,到“新街口”不足1 km。新中国成立以来,该地块一直被始建于民国时期的低矮民宅所占据;直至20世纪末,考虑到地块高昂的“潜在地租”和日趋“危旧化”的住宅状况,南京政府决定进行土地拍卖与再开发。2002年,南京长发房地产开发公司以2.01亿元的成交价从政府手中获得该地块17000 m2土地的开发权,折合楼面地价为2408元/m2;2005年,原址重建的长发中心一期住宅开盘销售,均价达11500元/m2;2007年,二期住宅销售均价上涨为16600元/m2,随着商品房售罄,开发商获得不菲的“预期租差”。

显示原图|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT

显示原图|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT图4拆迁前的利济巷地块、建设中与重建后的长发中心影像

注:2002年影像来自于南京市规划局;2005年和2010年影像来自于“google earth”。

-->Fig. 4Liji Lane plot prior to demolition, CFC under construction and after reconstruction

-->

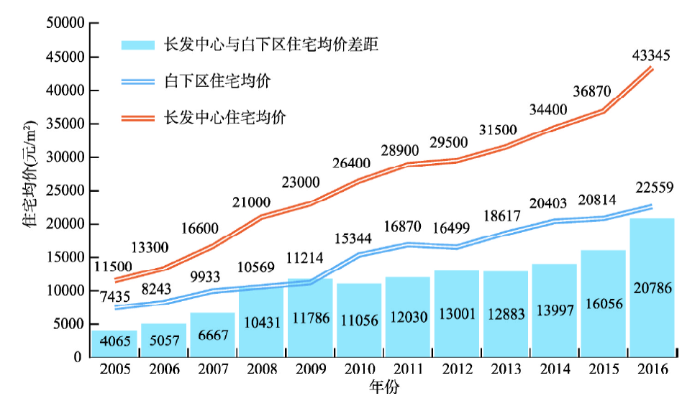

长发中心2005年开盘时,尽管每平米住宅均价比其所在白下区住宅均价高出4000元左右,但其综合居住优势和未来增值预期,依然吸引着大量具有高消费能力的中产群体竞相购买。事实也证明,新建的现代科技型住宅相比传统住宅而言,确实拥有更好的增值潜力,如图5所示,到2016年,在售价上,长发中心二手房均价上涨到43345元/m2,高出白下区住宅均价20000元/m2以上;在租金上,2016年长发中心住宅租金约为100元/月/m2,而紧邻的高层住宅科巷新寓的平均租金仅为50元/月/m2左右。长发中心更高的资产增值效率使住宅消费者与房地产开发商共享“预期租差”收益。

显示原图|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT

显示原图|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT图52005-2016年长发中心与白下区商品房均价走势

注:资源来源于城市房产网(http://nj.cityhouse.cn)。

-->Fig. 5Average price trends of CFC and commercial residential buildings in Baixia District during 2005-2016

-->

正如修正“租差”模型揭示的:政府通过土地征迁和土地出让获取“实际租差”,房地产开发商通过商品房建设和出售获得“预期租差”,城市政府和资本集团成为“拆—建”的积极推动者和最大受益者;而中产购房者家庭亦因住宅增值而获得部分“预期租差”,成为助推中产阶层化过程的消费群体保障。于是,在地方政府、房地产商、中产阶层联合金融机构,挖掘内城土地“租差”和再分配“资本化地租”的实践中,“资本”在“郊区化”的同时也产生向内城“回流”的趋向和动力,推动着内城中产阶层化的发生。

3.2 城市更新运动中的拆旧—建新式空间“高端化”重构

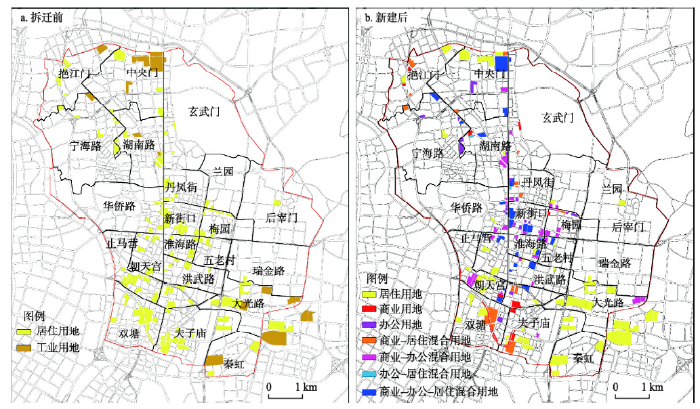

根据吴启焰[41]、陈果等[42]、刘玉亭等[43]对20世纪末南京城市居住空间格局的实证研究,发现集中居住着贫困群体的破旧民居,主要分布在南京内城的城中、城南夫子庙和城北下关码头等地区,具有“大分散,小集中”的特点。特别是“老城南”,历史上一直是南京城市人口最为密集的地区,以低矮、拥挤的传统民居为主。伴随南京旧城改造运动,上述地区中拥有优质区位和破败住宅的老旧邻里,因存在较大“租差”而首当其冲,被推倒重建为高档社区和商业办公场所,向“最高价值和最佳用途”(highest and best)[29]的土地利用方式转变,实现城市居住空间的现代化、高级化再生产。从2001-2011年南京内城拆迁—重建地块的空间布局和功能演变(图6)中可以看出:① 空间分布上,拆迁集中于城中、城南和城北地区,与城市低水平住宅和低收入群体的空间布局基本吻合,同时表现为沿路临水、单体地块规模小而分布散等布局特征。② 土地用途上,约90%的被拆迁地块用地性质为居住用地,另外10%为内城边缘地带零星分布的工业用地;重建后以商业、办公、居住混合用地性质为主,少量纯居住用地主要分布在城南和城北中央门附近。③ 利用效率上,出让140.43万m2土地上,规划总建筑面积369.57万m2,平均容积率达到2.63,单位面积土地利用强度远高于拆迁前。可见,在拆迁与重建过程中,内城以居住和工业职能为主的低矮民居和低效厂房,转变为以高端服务业和居住为主要职能的中高层现代建筑,实现了在土地功能、资本化地租、城市景观形象等方面的显著向上跃升。例如,拆迁前的“利济巷地块”曾拥挤密布着约185座1~2层的老旧民宅,历经大半个世纪多已破败不堪;而重建后的长发中心是由南京房地产公司和德国设计单位联合打造的办公—居住—商业综合体,由两栋高150 m的双塔商务办公楼、两栋135 m的高层住宅和商业广场组成,其设计获得诸多国内外奖项,堪称南京城市新地标型建筑和旧城更新的成功典范。

显示原图|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT

显示原图|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT图62001-2011年南京内城拆迁地块分布及土地利用性质变化

注:根据南京市房管局、拆迁办、国土局提供资料整理绘制。

-->Fig. 6Distribution of demolished plots and changes of land use in the inner city of Nanjing during 2001-2011

-->

然而,这种以土地“租差”为驱动、以推倒重建为形式的所谓“高端化”城市空间重构,在追求最大化土地利用效率的同时,也造成对城市传统文化和空间肌理的粗暴碾压。即Harvey眼中的资本“创造性破坏”(creative destruction)过程:资本通过反复的拆毁与重建完成对城市的投机行为和剩余价值再生产[44]。南京作为国家首批历史文化名城,其内城的大规模拆迁改造,亦表现为一种对原城市物质环境和人文社会景观的结构性破坏。如南京利济巷地区,是清代江宁织造署旧址所在地和曹雪芹出生地,与民国时期的总统府和中央饭店近在咫尺,改革开放后仍存有大量民国建筑和历史文化遗迹,却在内城拆迁改造中荡涤殆尽。再如“老城南”地区,在2006年以“打造一个新城南”口号下被成片拆毁,大量如颜料坊、牛市街区等历史文化街区和民居遭到破坏;一批具有珍贵历史价值的古街巷、古建筑和具有浓厚历史底蕴的文化地名和景观彻底消逝,造成难以挽回的损失。

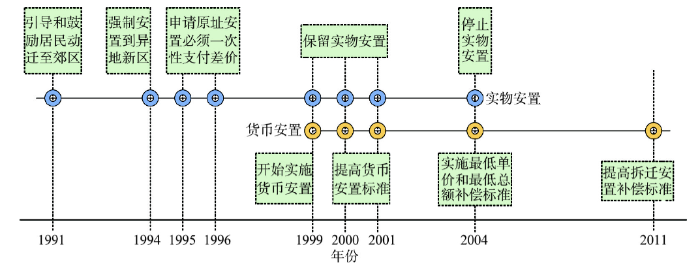

3.3 房价筛选机制下低收入群体外迁与中产阶层置换

城市拆旧建新过程必然在一定程度上伴随着居住群体的改变,特别是原住房面积较小的相对贫困家庭,在被拆迁后更倾向于向城市外围迁居。这点从南京拆迁安置补偿政策变迁上也能看出端倪(图7):1999年前以实物安置为主,但申请原址安置需要一次性支付差价;1999-2003年期间实施实物安置与货币安置并行政策,并提高货币补偿标准;至2004年正式以货币补偿和产权置换取代实物安置方式,引导拆迁家庭外迁至城市新区。应该说,政府实物化到货币化的拆迁补偿方式转变,客观上增加了被拆迁群体回迁内城的难度。 显示原图|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT

显示原图|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT图7南京市城市房屋拆迁安置补偿方式变迁

注:1991-2011年各版南京市城市房屋拆迁管理办法。

-->Fig. 7Changes of housing demolition and relocation compensation modes in Nanjing

-->

如表3所示,2001-2011年间,南京内城被拆迁安置家庭户均建筑面积为20.36 m2,户均补偿金额为10.56万元,相当于每平米建筑面积平均补偿5187元;在此期间,单位面积补偿标准虽逐渐提高,但增速明显滞后于内城房价的上涨速度;特别是拆迁量最大的2005-2007年期间,拆迁补偿标准未有明显提高,但内城房价则每平米上涨约2500元。限于原内城住房面积小,而且单位面积补偿金额远低于同期周边商品房价等因素,被拆迁家庭较难负担商品房或产权置换房。尤其是低收入群体,由于货币拆迁补偿总额低、申请贷款困难和偿还能力较弱等原因,不得不选择申购城市保障性住房,导致内城区的贫困阶层被迫迁出。根据南京住建局提供资料显示,在2001-2011年南京内城被迁拆群体中,有1.87万户低收入家庭的4.26万居民被动发生由内城到远郊区经济适用房的迁居。

Tab. 3

表3

表32001-2011年南京内城拆迁安置家庭户均住房面积和补偿金额情况

Tab. 3Average housing area and compensation of relocated family in the inner city of Nanjing during 2001-2011

| 年份 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 合计 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 户均拆迁面积(m2) | 19.49 | 20.97 | 22.61 | 25.22 | 20.63 | 18.54 | 25.16 | 17.97 | 15.81 | 16.38 | 13.45 | 20.36 |

| 户均补偿金额(万元) | 6.93 | 8.94 | 7.92 | 9.80 | 9.42 | 9.62 | 10.47 | 11.14 | 11.25 | 14.35 | 14.55 | 10.56 |

| 单位面积补偿(元/m2) | 3554 | 4621 | 3504 | 3886 | 4568 | 5189 | 4161 | 6201 | 7115 | 8758 | 10811 | 5187 |

| 内城住宅均价(元/m2) | 3678 | 4512 | 5190 | 6039 | 7435 | 8243 | 9933 | 10569 | 11214 | 15344 | 16870 | 9002 |

新窗口打开

再以“利济巷地块”拆迁为例,2002-2003年间共搬迁405户家庭,其中以货币补偿为主,每平米建筑面积平均补偿4833元;有约10%的低收入拆迁户符合申请保障房条件,迁至远郊区的春江新城、景明佳园和兴贤佳园,更多拆迁户则选择利用补偿款在市场上自由选择住房。尽管未能掌握被拆迁家庭迁出内城的比例,但不管是长发中心开盘11500元/m2的售价还是2.6元/月/m2的物管费用,都远超出当时大多数拆迁户的经济承受能力,导致原址回迁的居民寥寥。而按照长发中心“国际经理人公寓”的定位,取原住民而代之的,是450户原本分散的企业管理者、外企白领、外籍人士和其他高收入家庭。

简言之,当内城传统破败邻里被高档公寓和封闭社区取代,在住宅商品化和房价过滤机制下,一方面原住贫困家庭被迫外迁,另一方面,新富裕阶层和中产阶层凭借较强的经济实力逐渐集聚,并赋予邻里社区特定的阶层文化属性,实现对内城贫困阶层的所谓“社会清洗”(social cleansing)[45]。

4 基于地租的资本积累模式与利益分配博弈

在上述分析基础上,从资本循环和“租差”实践视角下的资本逻辑与政府效能;“租差”最大化取向下“新建中产阶层化”发生的时空规律;“租差”利益再分配中对被拆迁群体的多重剥夺等方面,探讨中产阶层化机理与效应问题。4.1 中产阶层化作为深度城市化和空间再生产策略

20世纪70年代,地理****Harvey通过引入“空间”因素,拓展了马克思的“资本循环”概念,提出资本循环的“三级回路”③(③市场中一般商品生产和消费为初级回路;随着一般商品生产的过度积累,过剩资本投向建成环境,此即二级回路;三级回路是指资本流向科技、研发和公共服务部门,以提高一二级回路的资本积累能力。)阐释资本流向与都市建成环境的关键作用,强调城市建成环境是解决资本“过度积累”④(④所谓资本过度积累危机,是指相对于资本可利用的机会,总体上产出过量资本所带来的过剩存货、利润萎缩、资本或劳动力闲置等问题。)(over accumulation)的重要场所[46]。当资本转移到建成环境回路,土地租金取代劳动力剩余价值,成为一个有利可图的商品,并通过空间再生产实现对资本循环矛盾的所谓“空间修复”(spatial fix)[47]。作为全球第二大经济体,中国工业化已进入相对产能过剩阶段,而城市化依然保持较快增长。不断增加的城市人口规模和居住需求,吸引工业部门过剩资本和追逐超额利润的国内外“热钱”涌入房地产市场,进入所谓资本循环的“二级回路”⑤ (⑤资本循环二级回路的投资方向主要有两种:一是生产活动所需固定资产(如机器设备、运输工具)和支持生产活动的物理结构(如厂房、办公场所);二是生活所需的耐用消费品(如家用电器、私家车)和建筑结构(如商铺、住宅、办公场所等)。当然,资本的二级回路也有过度积累的潜在风险,主要反映为不动产存量过剩。例如,经历本世纪以来房地产市场的超常规投资,中国部分城市或城市新区住宅供给量远超居民需求,导致出现商品房滞销甚至“空城”、“鬼城”现象。)。然而,中国的情况是,资本从制造业进入建成环境(主要指房地产市场),是与资本初级循环同时发生且相互支撑的[48],并非发生在资本过度积累导致经济危机或政治冲击之后,这与Harvey关于资本主义世界资本循环的描述有所不同。在土地私有体制下,通过完全市场化手段推进城市建成区的再开发成本高昂,资本通常会流向郊区未利用土地的房地产开发,郊区化的同时会造成内城的衰败。但中国特殊的经济制度使得权力与资本皆可以用较小的阻力来运作和支配空间[49],政府拥有城市土地所有权和空间再开发的主导权,城市政府通过相对低廉的补偿开展土地征收和房屋拆迁,提高城市土地利用效率和“潜在地租”,获取“实际租差”的同时也提升城市景观形象,避免内城衰败。经济发达城市有不断涌入的外来人口和较强的消费能力,城市地价和房价在旺盛的刚性或投资需求下保持快速上涨,能够产生足够“预期租差”吸引资本持续流向房地产市场。

城市企业主义(urban entrepreneurialism)[47]和土地导向积累模式(land-based accumulation)[50]下,建成环境(二级回路)成为城市政府资本循环的核心。城市空间对于城市政府而言,是一种交换价值与符号价值的共同体[51]。城市政府为增加财政收入和改善城市形象的“双重政绩”,致力于改善内城环境和基础设施,为投资者提供激励机制和优惠政策,迎合新兴中产阶层居住和消费需求,主导和推动内城拆建型中产阶层化运动。政府为化解城市建成环境投资过度积累风险,利用频繁变化的房地产调控政策,极力维持长期繁荣的房地产市场,保持商品房价持续、稳定上涨趋势⑥(⑥政府为获取持续不断增长的土地财政收入,同时提供足够吸引投资者的预期收益、刺激住房消费,必须调控房价保持平稳适度的增速,实现住房供给与消费的基本平衡,避免资本二级回路的过度积累。为促进房价和住房消费的稳步增长,政府通常以“降”为手段,例如降低购房首付比例、降低房贷利率、降低房屋交易税费、降低居住供地规模等;为防止房价增长过快造成不可控的政治经济风险,政府往往以“限”为工具,例如限购、限贷、限地价、限房价、限涨幅等。),吸引逐利性的资本和投资型的中产阶层流入,共享“预期租差”收益。显然,这种政府主导的“新建中产阶层化”或“拆建型中产阶层化”(slash-and-build gentrification)[19],已成为中国城市旧城区“再城市化”(re-urbanization)[9]的重要手段。政府通过扩大“租差”,引导资本涌向建成环境更新领域,推动内城空间、社会双重再生产,实现政府、投资者的双赢,是一种保持内城持续繁荣和充分挖潜空间“地租”价值的深度城市化策略。

4.2 垄断地租作用下城市中产阶层化的空间取向

从“租差”逻辑出发,发生中产阶层化的热点地区应具备的基本条件是:再开发成本和未来收益间存在足够大的利润空间。具体而言,一是土地回收成本要相对低,如国有土地上低矮的破败民居、集体土地上的“城中村”等;二是新建住宅价格要相对高且保值增值潜力要大,如城市中心、地铁沿线、优质景观地段和名校学区等。从南京内城中产阶层化的空间特征上看,城市原“棚户区”和贫困人口集聚区、城市中心新街口地区、十字形中轴线与秦淮河两岸等(图6),是住宅拆迁与重建的热点区域,与追求“租差”最大化的空间逻辑相符。当然,中产阶层化不止发生在内城[1, 52]。比如南京内城外的紫金山下、玄武湖、月牙湖和护城河畔等,原本由低收入城市居民或农村居民占据的优质景观地段,也明显存在中产阶层化社会—空间置换现象。不管是内城还是外围地区的中产阶层化,都是“垄断地租”(monopoly rent)[44]的资本化实现过程。土地作为企业型政府的最大“垄断资产”,通过土地一级市场改变所有权性质和用地性质(包括由农用地转变为城市建设用地),带给政府巨大的“增长溢价”[35];当具有独特性和不可复制性的土地(空间)被房地产商再开发为高档住宅,便成为“垄断产品”,通过土地二级市场,以“垄断价格”转让给购买力较强的中产阶层家庭;中产购房者的青睐旋即带动周边房价、地价的上涨,使政府在新一轮土地出让中获取更高的“垄断地租”。正如“空间资产”(spatial capital)[53]概念所揭示的,现代城市空间的“中心性”(centrality)是由空间(资产)的地租价值决定的。因此,中产阶层化一般发生在城市中心、依山傍水地段、名校学区、地铁站口等具有垄断性、稀缺性的城市空间,即指那些能够扩大“租差”和实现最大化“垄断地租”的城市“热点地带”(urban frontiers)[53]。

4.3 内城拆迁居民的利益剥夺与反中产阶层化行动

中产阶层化是一种资本主导的城市“空间殖民化”[54]和“剥夺性积累”(accumulation by dispossession)[55]过程。在中国中产阶层化“空间资产”转移和“租差”利润再分配中,政府和资本集团是最大获利者,从内城被迫迁居到郊区经济适用房的贫困家庭,则扮演着被“绝对剥夺”(absolute deprivation)的角色,承受着多重剥夺:其一,地租剥夺(ground rent dispossession)[56]。土地公有制下,城市居民相当于土地“租客”,部分拥有居住地“空间资产”。当拆迁发生时,政府主要补偿地面建筑物的价值,而对于地租的实际价值和增值预期的部分则不予补偿,导致补偿金额大大低于潜在资本化地租,造成对迁出居民经济利益的剥夺。

其二,空间剥夺(spatial deprivation)。Witten[57]研究发现,城市商业、医疗、教育和交通是评价空间剥夺程度最重要的指标。贫困群体由优势区位迁往郊区,势必会增加到城市中心的时空距离,降低与城中购物休闲、医疗卫生、体育娱乐、交通通讯、教育文化等公共资源要素的接近性和可及性,这是对居民住宅空间权利和附属价值的剥夺⑦(⑦2001-2011年期间,南京内城近两万户低收入家庭选择迁往恒盛嘉园、百水芊城、汇景家园、兴贤佳园、西善花苑和南湾营等保障房社区,均分布在距离城市中心10~20 km的郊区,以公交与地铁的公共交通方式出行至新街口,需要40~60 min,这造成外迁贫困居民交通、就业、生活成本增加,甚至就业机会减少。)。

其三,机会剥夺(opportunity deprivation)。空间分配的不公正与社会不公平存在密切关联[58],城市资源可接近性的降低本质上是对社会资源和发展机会的剥夺。对于贫困人口而言,被集中安置到公共交通欠发达、就业机会稀缺的城市远郊区,使他们很难摆脱被贫困捕获的命运,进而被固化在城市边缘地带[59]。更严重的是,由于远离城市优质教育资源,使这种贫困具有较强的代际传递性,可能造成贫困家庭继续“下沉”(downward movement)[60]。

伴随近年来持续上扬的房价,内城居民越来越清醒意识到居住区位的潜在市场价值,为维护自身权益和争取更多利益,“反中产阶层化”(anti-gentrification)情绪逐渐酝酿,不断出现如钉子户、上访户,甚至付诸暴力抗拆、自焚等极端“维权”行为。多数情况下,相对于西方城市抗议者主要为争取“原地不动的权力”(right to stay put)[61],中国城市反拆迁者更多是在争取符合其房屋“潜在地租”的经济补偿。尽管个体的维权行动难以形成具有影响力的结构性力量,但随着市民社会维权、组织机制的逐渐成熟和相关法律的逐步健全,特别是《物权法》的颁布,使“反增长联盟”(包括被拆迁户、部分媒体、****和公众人物等)正式具备了同“增长联盟”(包括地方政府和资本力量)开展利益博弈的法定权力。至此,在经历21世纪初大规模城市更新改造后,一方面内城所谓“棚户区”、“危旧房”已被拆除殆尽,另一方面,社会公平、旧城保护呼声日益高涨下城市拆迁成本攀高(“租差”缩小),意味着本轮“大拆大建”式的中产阶层化过程趋于结束,资本和“租差”驱动中产阶层化演进的作用方式和机制也将发生转变。

5 结论与展望

(1)根据Smith提出的是“资本”而不是“中产群体”驱动着中产阶层化的经典论断,“租差”的存在成为发生中产阶层化的前提条件。与西方经典“租差”模型不同,中国城市土地“租差”由两部分组成:土地公有和房屋贬值产生的“实际租差”,及房地产持续快速增值产生的“预期租差”。地方政府、房地产商和金融资本是“租差”利益分配中的最大获利者,因此也是城市中产阶层化最积极和强有力的推动者。(2)南京内城和“利济巷地块”案例验证了“实际租差”和“预期租差”的存在。城市政府通过扩大“租差”,鼓励和吸引资本投向建成环境(资本二级回路),共同推动内城更新改造。在城南夫子庙、城北下关等低矮破旧居民区,以及城中新街口、十字型主干道沿线、秦淮河两侧等存在最大“租差”的地段,率先出现以邻里物质环境跃升、低社会阶层被置换为显著特征的居住空间中产阶层化现象。

(3)相对于欧美市场化力量主导下的资本“回归”内城,中国政府主导型中产阶层化是“权力”与“资本”联手作用的结果,其实质是城市增长联盟操纵的“租差”资本化激活与资本循环增值过程。作为推动内城“再城市化”(re-urbanization)和社会空间高端化重构(re-construction)的重要策略,中国中产阶层化在充分发掘城市“空间资产”价值、改善城市景观、避免内城衰败和出现贫民窟等方面具有积极的意义。

(4)以提高“资本化地租”为导向的空间中产阶层化再生产,更加重视建成环境重建后的房地产增值,而相对忽视“租差”利益分配的公平性。例如拆迁中处于弱势地位的贫困群体,既不能获得真正体现其住房“潜在地租”的拆迁补偿,更无权参与到空间再开发后的资本增值收益分配,甚至因内城优质区位丧失、原有社会网络瓦解、就业机会和收入减少等原因而趋于“固化”在城市边缘和社会底层。

(5)随着内城拆迁改造高峰过去,大规模推倒重建式阶层演替将逐步放缓,并让位于与西方中产阶层化现象类似的个体渐进式阶层演替方式。因此,进一步研究需关注:中国中产阶层化过程是否具有波动性或周期性规律;“租差”理论如何解释修缮型的居住环境更新和侵入—演替式的阶层置换;中产阶层文化属性、家庭结构、生活方式等需求端非经济要素是否将发挥越来越重要的作用等问题。

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

参考文献 原文顺序

文献年度倒序

文中引用次数倒序

被引期刊影响因子

| [1] | . |

| [2] | . Schlichtman and Patch suggest that there is an elephant sitting in the academic corner: while urbanists often use ‘gentrification’ as a pejorative term in formal and informal academic conversation, many urbanists are gentrifiers themselves. Even though urbanists have this firsthand experience with the process, this familiarity makes little impact on scholarly debate. There is, Schlichtman and Patch argue, an artificial distance in accounts of gentrification because researchers have not adequately examined their own relationship to the process. Utilizing a simple diagnostic tool that includes ten common aspects of gentrification, they compose two autoethnographic memoirs to begin this dialogue. |

| [3] | . |

| [4] | . |

| [5] | . |

| [6] | . No abstract available. |

| [7] | |

| [8] | . Drawing on qualitative interviews in an inner Bristol (UK) neighbourhood, this paper offers some preliminary observations on the housing trajectories and strategies of a group of onward-moving gentrifiers. This indicates the potentially restricted nature of gentrification activity in the life-course and in the housing trajectories of these gentrifiers. The evidence points, on the one hand, to the diffuseness of gentrification, with a range of 'marginal', 'community' and 'corporate' gentrifiers all moving within the gentrified neighbourhood. On the other hand, those leaving the neighbourhood for contrasting locations and housing aesthetics experience a constrained form of gentrification: an inability to keep all social fields in play at the same time. They trade off current aesthetic display for longer-term investment in schooling and class reproduction. The structural and spatial arrangements of housing and education fields in different cities are thus critical in understanding how gentrification is expressed in terms of cultural capital, pointing to a provincial form of gentrification. |

| [9] | . New-build city-centre residential development in the UK has increasingly been identified as a form of ‘third-wave’ or ‘postrecession’ gentrification. The aim of this paper is, first, to extend our understanding of new, developer-led, residential development in the context of nonmetropolitan urban areas in the UK, which it does by means of a case study of the city of Bristol. The second aim is to revisit the issue of whether such residential development should be seen as a form of postrecession gentrification and to question the meaning of the term ‘gentrification’ as it has been increasingly used in a global context. This discussion draws both on a detailed case study of Bristol and on a critical reading of Davidson and Lees (2005, “New build ‘gentrification’ and London’s riverside renaissance”, Envronment and Planning A 37 1165 – 1190) account of new-build ‘gentrification’ in London’s riverside. In conclusion, it is argued that these forms of residential development and investment flows reflect a powerful and complex set of processes which it is important to understand. In contrast to Davidson and Lees, however, the conclusion is also that the extension of the term ‘gentrification’ to embrace such forms of development stretches it beyond the point at which it retains utility or meaning. |

| [10] | . This paper critically reviews the major theories of gentrification which have emerged over the last 10 years and the debate which has surrounded them. It argues that the reason why the gentrification debate has attracted so much interest, and has been so hard fought, is that it is one of key theoretical battlegrounds of contemporary human geography which highlights the arguments between structure and agency, production and consumption, capital and culture, and supply and demand. It also argues that each of the two major explanations which have been advanced to account for gentrification (the rent gap and the production of gentrifiers) are partial explanations, each of which is necessary but not sufficient. Finally, it argues that an integrated explanation for gentrification must involve both explanation of the production of devalued areas and housing and the production of gentrifiers and their specific consumption and reproduction patterns. |

| [11] | . ABSTRACT The term rural gentrification is examined and contrasted with contemporary debates over urban gentrification. A common root, in the displacement of a working-class populace by middle-class incomers, is identified and also criticised. Attention is drawn to debates current within urban studies concerning the definition of gentrification as a process of capital investment or as a means to purchase particular lifestyles, the role of reproductive work and service provision, and the possibility of diverse types of gentrifiers and processes of gentrification. The paper investigates, through a substantive study of households in four villages in Gower, whether some of these arguments can illuminate understandings of rural gentrification. Claims that gentrification is necessarily associated with home owners acting as capitalist developers or with an emergent service class are questioned and the possibility of arginal gentrifiers is raised. It is also suggested that asymmetries in class positions of householders may be constitutive of rural gentrification. Finally it is argued that comparative work should be undertaken to draw out both the commonalities and differences between rural and urban gentrification and also within gentrification in various rural localities. |

| [12] | . Abstract The gentrification literature since the mid-1990s is reappraised in light of the emergence of processes of post-recession gentrification and in the face of recent British and American urban policy statements that tout gentrification as the cure-all for inner-city ills. Some tentative suggestions are offered on how we might re-energize the gentrification debate. Although real analytical progress has been made there are still 'wrinkles' which research into the 'geography' of gentrification could address: 1) financifiers - super-gentrification; 2) third-world immigration - the global city; 3) black/ethnic minority gentrification - race and gentrification; and 4) liveability/urban policy - discourse on gentrification. In addition, context, temporality and methodology are argued to be important issues in an updated and rigorous deconstruction of not only the process of gentrification itself but also discourses on gentrification. |

| [13] | . This case study updates a long-running investigation into the revitalisation of inner Adelaide previously reported in Urban Studies in 1981 and 1991. Its value is two-fold: first, it provides an opportunity to review critically the fate of gentrification in Australia under economic conditions that others would claim have not always been favourable during the 1990s; and, secondly, it highlights the strategic role of a public housing authority as a lead agency in the process of urban revitalisation. The paper uses data on intercensal change together with an overview of the state government's urban investment policy to argue that the class transformation of inner Adelaide is now effectively complete. During the past decade, there has been a distinct improvement in the fortunes of the inner western suburbs which had previously suffered from long-term decline. The State's Inner Western Program has been instrumental in remediating badly degraded industrial land and rezoning an unused transport corridor through these suburbs and helping to lever private investment in the housing sector. Hence the housing reinvestment and class changeover normally associated with gentrification has proceeded apace right through the 1990s. After 30 years, the circle of regeneration has almost been completed on all four sides of the City of Adelaide. |

| [14] | . |

| [15] | . In a recent conference paper Lambert and Boddy (2002) questioned whether new-build residential developments in UK city centres were examples of gentrification. They concluded that this stretched the term too far and coined 0900residentialisation0964 as an alternative term. In contrast, we argue in this paper that new-build residential developments in city centres are examples of gentrification. We argue that new-build gentrification is part and parcel of the maturation and mutation of the gentrification process during the post-recession era. We outline the conceptual cases for and against new-build 0900gentrification0900, then, using the case of London's riverside renaissance, we find in favour of the case for. |

| [16] | . ABSTRACT This paper revisits the ‘geography of gentrification’ thinking through the literature on comparative urbanism. I argue that given the ‘mega-gentrification’ affecting many cities in the Global South gentrification researchers need to adopt a postcolonial approach taking on board critiques around developmentalism, categorization and universalism. In addition they need to draw on recent work on the mobilities and assemblages of urban policies/policy-making in order to explore if, and how, gentrification has travelled from the Global North to the Global South. |

| [17] | . This paper reveals how urban theories traditionally rooted in northern cities and academies are challenged and redeveloped by southern perspectives. Critiques of urban theory as narrowly northern (or Anglo-American) have recently emerged, spawning the comparative urbanism movement that calls for urban theories to be open to the experiences of all cities. Using the example of the sale of state-subsidised houses in South Africa, this research uses two parallel concepts, gentrification and downward raiding, to challenge the northern empirical focus of urban theory. Despite describing similar processes of urban class-based change, the concepts are rarely considered analogous, entrenched in divergent empirical contexts and academic literatures. While gentrification debates largely reference the northern central city, downward raiding is reserved for the southern 0900slum0964. In contrast, this research develops 0900hybrid gentrification0964 as a concept and methodological approach that demonstrates how non-northern urban experiences can and should create and refine urban theory. |

| [18] | . Gentrification, or the class-based restructuring of cities, is a process that has accrued a considerable historical depth and a wide geographical compass. But despite the existence of what is otherwise an increasingly rich literature, little has been written about connections between schools and the middle class makeover of inner city districts. This paper addresses that lacuna. It does so in the specific context of the search by well-off middle class parents for places for their children in leading state schools in the inner city of Nanjing, one of China largest urban centres, and it examines a process that we call here jiaoyufication. Jiaoyufication involves the purchase of an apartment in the catchment zone of a leading elementary school at an inflated price. Gentrifying parents generally spend nine years (covering the period of elementary and junior middle schooling) in their apartment before selling it on to a new gentrifying family at a virtually guaranteed good price without even any need for refurbishment. Jiaoyufication is made possible as a result of the commodification of housing alongside the increasingly strict application of a catchment zone policy for school enrolment. We show in this paper how jiaoyufication has led to the displacement of an earlier generation of mainly working class residents. We argue that the result has been a shift from an education system based on hierarchy and connections to one based on territory and wealth, but at the same time a strangely atypical sclerosis in the physical structure of inner city neighbourhoods. We see this as a variant form of gentrification. |

| [19] | . This commentary sets out to make a claim for gentrification to be understood from the Global East. I argue that a regional approach to gentrification can nurture a contextually informed but theoretically connected comparative urbanism, contributing to the comparative urbanist project by providing an appropriate point of contact between local context and universalising theories. In the process, I attempt to partially destabilise the concept of gentrification and then re-centre it in the Global East. Any comparative exercise is not a straightforward process; on the contrary, it is fraught with epistemological, theoretical and methodological stumbling blocks regions are slippery and often diverse; diversity can be hard to bottle and label along theoretical lines; methods work more smoothly in discrete settings. But it is an exercise worth undertaking; the regional is the middle stratum that allows the locally specific to speak to planetary trends, and planetary trends to find local purchase. In the pages that follow I map out a number of recognisable types of gentrification in East Asia. I then use these to transcend the region and cut across the Global North / Global South binary that bedevils so much theory-making. The aim, addressed specifically in the final section, is to use these claims for gentrification in the Global East to speak back to and, hopefully, enrich urban theory-making and contribute to discussion of what is becoming known as planetary gentrification (Lees et al., forthcoming). |

| [20] | |

| [21] | . |

| [22] | . |

| [23] | . |

| [24] | Abstract In Shanghai, globalised urban images and a well-functioning accumulation regime are enthusiastically sought after by urban policy, and explicitly promoted as a blueprint for a civilised city life. The city is celebrating its thriving neo-liberal urbanism by implementing enormous new-build gentrification, mostly in the form of demolition ebuild development involving direct displacement of residents and landscapes. This study aims to understand demographic changes and the socioeconomic consequences of new-build gentrification in central Shanghai. The paper first examines demographic changes between 1990 and 2000 in central Shanghai, i.e. the changing distribution of potential gentrifiers and displacees. It then looks into two cases of new-build gentrification projects in central Shanghai, to compare residents' socioeconomic profiles in old neighbourhoods and new-build areas. This study also examines the impacts of gentrification on displacees' quality of life and socioeconomic prospects. Because the enlarging middle class and the pursuit of wealth-induced growth by the municipal government are turning the central city into a hotspot of gentrification, inequalities in housing and socioeconomic prospects are being produced and intensified in the metropolitan area. This study thus emphasises that critical perspectives in gentrification research are valuable and indispensable. Copyright 2009 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. |

| [25] | . . |

| [26] | . . |

| [27] | . 从租差理论与绅士化的关系入手,梳理了租差理论的缘由、脉络与拓展,指出租差理论是城市空间再开发问题的有力工具,但难以在城市化和城市空间扩展快速推进的背景下应用。基于特征价格法研究方法,通过引入场所价格和区位价格的概念,考察了潜在地租、实际地租的不同组合类型以及租差的演变情况,区分不同的城市空间循环演化模式,为分析城市空间再开发的时机、难易程度等问题提供了新的分析思路与框架。 . 从租差理论与绅士化的关系入手,梳理了租差理论的缘由、脉络与拓展,指出租差理论是城市空间再开发问题的有力工具,但难以在城市化和城市空间扩展快速推进的背景下应用。基于特征价格法研究方法,通过引入场所价格和区位价格的概念,考察了潜在地租、实际地租的不同组合类型以及租差的演变情况,区分不同的城市空间循环演化模式,为分析城市空间再开发的时机、难易程度等问题提供了新的分析思路与框架。 |

| [28] | . Abstract Consumer sovereignty hypotheses dominate explanations of gentrification but data on the number of suburbanites returning to the city casts doubt on this hypothesis. In fact, gentrification is an expected product of the relatively unhampered operation of the land and housing markets. The economic depreciation of capital invested in nineteenth century inner-city neighborhoods and the simultaneous rise in potential ground rent levels produces the possibility of profitable redevelopment. Although the very apparent social characteristics of deteriorated neighborhoods would discourage redevelopment, the hidden economic characteristics may well be favorable. Whether gentrification is a fundamental restructuring of urban space depends not on where new inhabitants come from but on how much productive capital returns to the area from the suburbs. |

| [29] | . |

| [30] | . Whereas authors have frequently alluded to an adversarial politics among the new middle class of professional and managerial workers, surveys and electoral returns confirm a generally conservative disposition in this group as a whole. In this paper I seek to specify a social location for left -liberal politics among a distinctive cadre of social and cultural profes sionals, the cultural new class. This cadre also bears a distinct geographical identity, with an overconcentration in the central cities of large metropolitan areas, not least in their gentrifying districts. The part played since 1968 by the cultural new class in these gentrifying districts in redefining the urban politics of Toronto, Montreal, and Vancouver is examined. In particular, the role of a gentrifying middle class in challenging a postwar hegemony of growth boosterism practised by the conservative regimes in all three cities, and their parallel attempt to sustain an altemative regime of reform politics, are assessed. |

| [31] | . Gentrification and the middle classes |

| [32] | . |

| [33] | . . |

| [34] | . 在城市更新改造过程中,中产阶层化现象开始在我国城市中出现。中国中产阶层化是在全球化背景 下,由政府推动,投资者、金融机构和中产阶层等共同参与的社会空间再造过程。为了解我国现阶段中产阶层化的发育程度与演化机制,采取实地调研与问卷访谈等 研究手段,对南京中产阶层化过程进行探讨。认为南京中产阶层化过程经历了孕育、发生和快速发展三个时期;宏观上表现为中产阶层向城市中心集聚、封闭社区整 体植入等空间特征;微观上中产阶层化社区文化与阶层认同正在不断发育与成熟。在中产阶层化过程中,需要警惕如空间私有化、阶层排斥加剧与公平性缺失等社会 负面效应。随着大规模城市拆迁接近尾声和《物权法》等法规政策的出台,中国以城市更新为契机的第一波中产阶层化过程即将进入平稳缓行阶段。 . 在城市更新改造过程中,中产阶层化现象开始在我国城市中出现。中国中产阶层化是在全球化背景 下,由政府推动,投资者、金融机构和中产阶层等共同参与的社会空间再造过程。为了解我国现阶段中产阶层化的发育程度与演化机制,采取实地调研与问卷访谈等 研究手段,对南京中产阶层化过程进行探讨。认为南京中产阶层化过程经历了孕育、发生和快速发展三个时期;宏观上表现为中产阶层向城市中心集聚、封闭社区整 体植入等空间特征;微观上中产阶层化社区文化与阶层认同正在不断发育与成熟。在中产阶层化过程中,需要警惕如空间私有化、阶层排斥加剧与公平性缺失等社会 负面效应。随着大规模城市拆迁接近尾声和《物权法》等法规政策的出台,中国以城市更新为契机的第一波中产阶层化过程即将进入平稳缓行阶段。 |

| [35] | . 绅士化是西方国家再城市化过程中,城市中心区更新(复兴)的一种新的社会空间现象。Smith的租差理论从生产/供给的视角,认为绅士化出现的根本原因在于资本的逐利性。基于马克思主义的分析范式与路线,借助土地产权的理论视角,对Smith的租差理论进行重新诠释,认为绅士化与再开发,不仅是资本主导的“回归城市运动”,更是资本与权利驱动下的城市空间再生产过程。由再开发转向再生产,从关注城市物质空间的变迁转而关注社会空间与物质空间的互动机理及其相应的空间效应,将是未来包括中国在内的城市空间研究的必然趋势。 . 绅士化是西方国家再城市化过程中,城市中心区更新(复兴)的一种新的社会空间现象。Smith的租差理论从生产/供给的视角,认为绅士化出现的根本原因在于资本的逐利性。基于马克思主义的分析范式与路线,借助土地产权的理论视角,对Smith的租差理论进行重新诠释,认为绅士化与再开发,不仅是资本主导的“回归城市运动”,更是资本与权利驱动下的城市空间再生产过程。由再开发转向再生产,从关注城市物质空间的变迁转而关注社会空间与物质空间的互动机理及其相应的空间效应,将是未来包括中国在内的城市空间研究的必然趋势。 |

| [36] | . Property-led urban redevelopment in contemporary Chinese cities often results in the demolition of many historical buildings and neighbourhoods, invoking criticisms from conservationists. In the case of Beijing, the municipal government produced a series of documents in the early 2000s to implement detailed plans to conserve 25 designated historic areas in the Old City of Beijing. This paper aims to examine the recent socio-economic and spatial changes that took place within government-designated conservation areas, and scrutinise the role of the local state and real estate capital that brought about these changes. Based on recent field visits and semi-structured interviews with local residents and business premises in a case study area, this paper puts forward two main arguments. First, Beijing’s urban conservation policies enabled the intervention of the local state to facilitate revalorisation of dilapidated historic quarters and to release dilapidated courtyard houses on the real estate market. The revalorisation was possible with the participation of a particular type of real estate capital that had interests in the aesthetic value that historic quarters and traditional courtyard houses provided. Second, the paper also argues that economic benefits generated by urban conservation, if any, were shared disproportionately among local residents, and that local residents’ lack of opportunities to ‘voice out’ further consolidated the property-led characteristic of urban conservation, which failed to pay attention to social lives. |

| [37] | . |

| [38] | . China since the late 1970s has implemented a series of reforms and has undergone profound changes. This paper analyzes the three fundamental processes of China's economic reforms ecentralization, marketization, and globalization, and argues that an understanding of these triple transitions is necessary for a better understanding of regional development in China. These changes also have had significant implications for the development of regions, as the central state is no longer monopolizing the regional development process. It is speculated that China's regions will remain fragmented and the coastal-interior divide may persist. |

| [39] | . . |

| [40] | |

| [41] | |

| [42] | . . |

| [43] | . 本文以南京市为例,检查转型期城市贫困人口的空间分布特征,并着重分析贫困人口集中的低收入邻里的类型、特征及其产生机制。研究表明,转型期我国城市贫困人口的空间分布表现为在邻里或社区层面上的集中。城市贫困人口在邻里层次上的集聚,导致三种类型低收入邻里的产生,包括老城衰退邻里、退化的工人新村和农民工集聚区(城中村)。分析表明,这些低收入邻里的产生源于国家导向的城市发展政策和国家福利住房供应制度,并在住房市场化和房地产导向的城市发展过程中得以强化。基于南京市的实证分析和实地调查,城市贫困人口的空间分布状况和低收入邻里的特征被检查,低收入邻里的产生机制得以验证。 . 本文以南京市为例,检查转型期城市贫困人口的空间分布特征,并着重分析贫困人口集中的低收入邻里的类型、特征及其产生机制。研究表明,转型期我国城市贫困人口的空间分布表现为在邻里或社区层面上的集中。城市贫困人口在邻里层次上的集聚,导致三种类型低收入邻里的产生,包括老城衰退邻里、退化的工人新村和农民工集聚区(城中村)。分析表明,这些低收入邻里的产生源于国家导向的城市发展政策和国家福利住房供应制度,并在住房市场化和房地产导向的城市发展过程中得以强化。基于南京市的实证分析和实地调查,城市贫困人口的空间分布状况和低收入邻里的特征被检查,低收入邻里的产生机制得以验证。 |

| [44] | . No Abstract available for this article. |

| [45] | . Globalization and liberal economic reforms provide both opportunities and threats for developing cities. It can bring much needed capital and economic development but also at the possible cost of displacement and marginalization. Metro Manila contributes US$7.7 billion to the Philippine economy by remaining competitive in attracting and facilitating the flow of capital. However, this economic development translates to displacement, with its very citizens being affected. We analyze this phenomenon through the existing literature on Metro Manila and gentrification. This paper addresses the key questions: Who are the key players in Metro Manila’s gentrification? What are the implications of their actions? In this analysis, we use Neil Smith’s gentrification framework. We find that the key players involved in this development have prioritized competitiveness by facilitating capital in a globalized world at the cost of ignoring Metro Manila’s marginalized households. To continually ensure capital, the private sector has captured Metro Manila with the urban elites benefiting the most. Metro Manila has been successful in attracting capital and economic progress, but exclusively for consumers who can afford it. While this paper is primarily descriptive in nature, we hope to pose this as a challenge for government to pursue stronger inclusive policies in the urban capital. |

| [46] | . L'objectif de cet article est d'esquisser une problématique générale pour l'interprétation du processus urbain capitaliste. A cette fin, deux thèmes apparentés, l'accumulation et la lutte de classes, sont examinés. Un examen de la théorie marxiste de l'accumulation mène à une compréhension théorique du r00le de l'investissement dans le cadre bàti en relation avec l'ensemble de la structure et des contradictions du processus d'accumulation. Plus précisément, l'investissement dans le cadre b09ti est per04u en relation avec les différentes formes de crise qui peuvent surgir sous le capitalisme. Une séléction d'exemples empiriques est présentée et discutée afin d'illustrer comment le support théorique est relié à l'évidence historique. Ce04i permet de mettre à l'intérieur d'une perspective théorique cohérente les ‘long cycles’ d'investissement observés, ainsi que les changements geógraphique des fluxes d'investissements. Ensuite la manière dont le cadre b09ti lui-même exprime et contribu aux crises capitalistes est examinée. Il est demontré que sous le capitalisme il existe une lutte perpetuelle selon laquelle le capital essaye de construire un environnement propre à son image seulement pour le détruire avec la réapparition d'une nouvelle crise. L'analyse considère alors comment la lutte de classes—c'est à dire la réaction organisée de la force du travail aux déprédations du capital—influence la direction et la forme de l'investissement dans le cadre b09ti. D'un intérêt particulier est la manière dont la lutte de classes au lieu du travail se trouve déplacée à travers le processus urbain vers des luttes centrées autour de la reproduction de la force du travail au foyer. Quelques exemples de ces luttes sont présentés afin d'illustrer comment elles se rattachent à la lutte fondamentale au point de production en même temps qu'elles influencent la direction et la forme de l'investissement dans le cadre b09ti. |

| [47] | . In recent years, urban governance has become increasingly preoccupied with the exploration of new ways in which to foster and encourage local development and employment growth. Such an entrepreneurial stance contrasts with the managerial practices of earlier decades which primarily focussed on the local provision of services, facilities and benefits to urban populations. This paper explores the context of this shift from managerialism to entrepreneurialism in urban governance and seeks to show how mechanisms of inter-urban competition shape outcomes and generate macroeconomic consequences. The relations between urban change and economic development are thereby brought into focus in a period characterised by considerable economic and political instability. |

| [48] | . This paper uses Guangzhou0964s experience of hosting the 2010 Asian Games to illustrate Guangzhou0964s engagement with scalar politics. This includes concurrent processes of intra-regional restructuring to position Guangzhou as a central city in south China and a 0900negotiated scale-jump0964 to connect with the world under conditions negotiated in part with the overarching strong central state, testing the limit of Guangzhou0964s geopolitical expansion. Guangzhou0964s attempts were aided further by using the Asian Games as a vehicle for addressing condensed urban spatial restructuring to enhance its own production/accumulation capacities, and for facilitating urban redevelopment projects to achieve a 0900global0964 appearance and exploit the city0964s real estate development potential. Guangzhou0964s experience of hosting the Games provides important lessons for expanding our understanding of how regional cities may pursue their development goals under the strong central state and how event-led development contributes to this. |

| [49] | |

| [50] | |

| [51] | . 将制度的转轨与市场社会的形成 过程以及与此相伴随的空间的重构,概括为中国当代政治、经济与空间的转型过程。在转型背景下,指出空间再开发已经成为城市空间政治博弈的焦点,并采用"政 府、经济精英、市民与城市规划"的政治经济分析框架,解释了中国转型过程中政治博弈权力分配不均衡的现状,这种状况导致了再开发过程中利益分配的不均等。 最后针对权力分配与政治博弈的不均衡,提出了基本的治理对策。 . 将制度的转轨与市场社会的形成 过程以及与此相伴随的空间的重构,概括为中国当代政治、经济与空间的转型过程。在转型背景下,指出空间再开发已经成为城市空间政治博弈的焦点,并采用"政 府、经济精英、市民与城市规划"的政治经济分析框架,解释了中国转型过程中政治博弈权力分配不均衡的现状,这种状况导致了再开发过程中利益分配的不均等。 最后针对权力分配与政治博弈的不均衡,提出了基本的治理对策。 |

| [52] | |

| [53] | . In this paper we are critical of the fact that the gentrification literature has moved away from discussions about the reclaiming of locational advantage as a marker of gentrifiers’ social distinction within the middle classes. We begin the process of re/theorising locational advantage as ‘spatial capital’ focusing on the mobility practices of new-build gentrifiers in Swiss core cities. Gentrification is a relatively new process in Swiss cities and is dominated by new-build developments in central city areas. We focus on two case studies: Neuch09tel and the Zurich West area of Zurich. We show that Swiss new-build gentrifiers have sought locational advantage in the central city, and in so doing have gained the ‘spatial capital’ that they need to negotiate and cope with dual career households and the restrictive job markets of Swiss cities. The mobility practices of these gentrifiers show how they are both hyper-mobile and hyper-fixed, they are mobile and rooted/fixed. |

| [54] | The relationship between gentrification and globalisation has recently become a significant concern for gentrification scholars. This has involved developing an understanding of how gentrification has become a place-based strategy of class (re)formation during an era in which globalisation has changed sociological structures and challenged previously established indicators of social distinction. This paper offers an alternative reading of the relationship between gentrification and globalisation through examining the results of a mixed method research project which looked at new-build gentrification along the River Thames, London, UK. This research finds gentrification not to be distinguished by the gentrifer-performed practice of habitus within a 'global context'. Rather, the responsibility for gentrification, and the relationship between globalisation and gentrification, is found to originate with capital actors working within the context of a neoliberal global city. In order to critically conceptualise this form of gentrification, and understand the role of globalisation within the process, the urban theory of Lefebvre is drawn upon. |

| [55] | |

| [56] | . ABSTRACT The rent gap theory, a consistent explanation of gentrification in inner-city spaces, sees a growing disparity between capitalized ground rent (CGR) and potential ground rent (PGR) as a catalyst for large-scale property reinvestment and thence gentrification. In historical working-class Santiago's peri-centre (inner city), not only is there a measurable rent gap, but a state-subsidized market in high-density urban renewal based on the accumulation of increased CGR by a few large-scale developers. This article focuses on a low-income municipality of Santiago, which has a local government that aims to attract this market via the liberalization of its local building regulations (seeking to increase the PGR), and deliberate underperformance in a national programme for housing upgrading (seeking to devalue the CGR in spaces previously targeted for renewal). It is observed how, in this city, two forms of ground rent exist, a lower one capitalized by current owner-occupiers (CGR-1) and a higher one capitalized by the market agents of renewal (CGR-2). This is seen as a form of social dispossession of the ground rent and a necessary condition for gentrification. It is concluded that the state-led strategy of urban renewal in Santiago needs to be refocused on more participative forms of distribution of the rent gap.ResuméD'après la théorie du différentiel de loyer, qui éclaire de fa04on cohérente la gentrification des espaces centraux des villes, l'écart grandissant entre loyer foncier capitalisé (CGR) et loyer foncier potentiel (PGR) constitue un catalyseur de réinvestissement immobilier à grande échelle, donc de gentrification. Dans le péricentre historique et ouvrier de Santiago du Chili, il se crée non seulement un écart de prix mesurable, mais aussi un marché subventionné par l'07tat portant sur la rénovation de quartiers urbains à forte densité et fondé sur l'accumulation des CGR (croissants) par quelques grands promoteurs. L'article s'intéresse à une municipalité défavorisée de Santiago dont le gouvernement s'efforce d'attirer ce marché en libéralisant ses réglementations locales sur la construction (afin d'augmenter le PGR) et en produisant délibérément des résultats insuffisants dans le cadre d'un programme national d'amélioration des logements (afin de déprécier le CGR dans les espaces ciblés préalablement pour rénovation). Dans cette ville, on peut observer deux types de loyer foncier, un type inférieur capitalisé par les propriétaires occupants actuels (CGR-1) et un type supérieur capitalisé par les agents opérant sur le marché de la rénovation (CGR-2). La situation est considérée comme une forme de dépossession sociale du loyer foncier, et comme une condition nécessaire à la gentrification. Pour conclure, la stratégie de rénovation urbaine que l'07tat applique à Santiago doit être recentrée sur des formes plus participatives de répartition du différentiel de loyer. |

| [57] | . |

| [58] | . Since 2001, there has been a radical shift in the governance of urban land and housing markets in Turkey from a 0900populist0964 to a 0900neo-liberal0964 mode. Large 0900urban transformation projects0964 (UTPs) are the main mechanisms through which a neo-liberal system is instituted in incompletely commodified urban areas. By analysing two UTPs implemented in an informal housing zone and an inner-city slum in Istanbul, the paper discusses the motivations behind, the socioeconomic consequences of and grassroots resistance movements to the new urban regime. The analysis shows that the UTPs predominantly aim at physical and demographic upgrading of their respective areas rather than improving the living conditions of existing inhabitants, thus instigating a process of property transfer and displacement. It also demonstrates that the property/ tenure structure of an area plays the most important role in determining the form and effectiveness of grassroots movements against the UTPs. |

| [59] | . 采用南京内城区2001-2011年期间10843户贫困家庭的拆迁安置数据,探讨内城区户籍贫困空间格局及其重构特征。通过空间自相关与空间聚类等研究方法,对城市拆迁发生前内城区22个街道的贫困家庭分布格局分析发现:①样本贫困群体在街道尺度上社会经济属性相对均质,主要贫困属性因子的空间自相关性不强;②内城区户籍贫困空间格局具有良好的历史延续性,总体上呈分散布局并遵循着自然渐进式的空间演化模式;③拆迁安置导致内城区贫困空间发生由中心至边缘、由分散到集中的重构,而且这种贫困空间边缘化过程具有强烈的不可逆性;④贫困家庭的物质居住条件通过拆迁安置得以改善,代价是因搬离内城而远离商业区、重点中小学、三甲医院和地铁站点等城市优质公共资源。内城区贫困空间剥夺式重构过程中,城市优势区位的丧失有可能导致贫困家庭的交通、就业与生活成本增加,向上流动机会减少。 . 采用南京内城区2001-2011年期间10843户贫困家庭的拆迁安置数据,探讨内城区户籍贫困空间格局及其重构特征。通过空间自相关与空间聚类等研究方法,对城市拆迁发生前内城区22个街道的贫困家庭分布格局分析发现:①样本贫困群体在街道尺度上社会经济属性相对均质,主要贫困属性因子的空间自相关性不强;②内城区户籍贫困空间格局具有良好的历史延续性,总体上呈分散布局并遵循着自然渐进式的空间演化模式;③拆迁安置导致内城区贫困空间发生由中心至边缘、由分散到集中的重构,而且这种贫困空间边缘化过程具有强烈的不可逆性;④贫困家庭的物质居住条件通过拆迁安置得以改善,代价是因搬离内城而远离商业区、重点中小学、三甲医院和地铁站点等城市优质公共资源。内城区贫困空间剥夺式重构过程中,城市优势区位的丧失有可能导致贫困家庭的交通、就业与生活成本增加,向上流动机会减少。 |

| [60] | |

| [61] | . |