,1, 闫爱玲2, 孙磊3, 张国军1, 王晓玥1, 任建成1, 徐海英

,1, 闫爱玲2, 孙磊3, 张国军1, 王晓玥1, 任建成1, 徐海英 ,1

,1Effects of Low Temperature Storage on Monoterpenes in Table Grape

WANG HuiLing ,1, YAN AiLing2, SUN Lei3, ZHANG GuoJun1, WANG XiaoYue1, REN JianCheng1, XU HaiYing

,1, YAN AiLing2, SUN Lei3, ZHANG GuoJun1, WANG XiaoYue1, REN JianCheng1, XU HaiYing ,1

,1通讯作者:

责任编辑: 赵伶俐

收稿日期:2020-04-29接受日期:2020-08-19网络出版日期:2021-01-01

| 基金资助: |

Received:2020-04-29Accepted:2020-08-19Online:2021-01-01

作者简介 About authors

王慧玲,E-mail:

摘要

关键词:

Abstract

Keywords:

PDF (1216KB)元数据多维度评价相关文章导出EndNote|Ris|Bibtex收藏本文

本文引用格式

王慧玲, 闫爱玲, 孙磊, 张国军, 王晓玥, 任建成, 徐海英. 低温贮藏对鲜食葡萄果实中单萜化合物的影响[J]. 中国农业科学, 2021, 54(1): 164-178 doi:10.3864/j.issn.0578-1752.2021.01.012

WANG HuiLing, YAN AiLing, SUN Lei, ZHANG GuoJun, WANG XiaoYue, REN JianCheng, XU HaiYing.

开放科学(资源服务)标识码(OSID):

0 引言

【研究意义】葡萄具有很高的营养价值,且味美多汁,是世界五大名果之一。然而葡萄生产具有地域性和季节性的特点,要实现各地周年供应新鲜葡萄,发展贮藏保鲜事业很有必要。低温冷藏是现代葡萄贮藏保鲜的主要方式[1]。随着生活水平的提高,人们对葡萄品质的要求也越来越高。香气是构成葡萄品质的主要因素之一,特别是玫瑰香味深受消费者喜欢[2]。研究采后低温贮藏期间玫瑰香气成分的变化规律,将为建立更科学的葡萄贮藏体系,保证葡萄优良风味品质提供理论和实践依据。【前人研究进展】单萜是葡萄果实中含量最丰富的萜类化合物,被认为是玫瑰香味的主要呈香物质[3]。根据游离态单萜类化合物的含量高低,欧洲种酿酒葡萄品种被分为玫瑰香型(游离态单萜化合物总量高达6 mg?L-1)、非玫瑰香芳香型(游离态单萜化合物总量达1—4 mg?L-1)和非芳香型(游离态单萜化合物总量低于1 mg?L-1)3类[4]。在葡萄果实中单萜化合物以游离态和糖苷结合态存在,一般认为游离态是挥发性化合物,可以被直接感知,与葡萄浆果的香气有关。而糖苷结合态单萜不易挥发,对葡萄的香气没有直接贡献,但是它们可以通过增加水解作用而转化为游离态化合物,从而改变葡萄的芳香特性[5]。影响单萜化合物积累的因素很多,除了遗传基因组成,还受生长环境及栽培技术措施等外在因素的影响[6,7,8]。然而目前对葡萄单萜成分的研究主要集中在采前阶段,在低温贮藏过程中,果实的理化性质会发生或多或少的变化[9]。科学家对葡萄在低温贮藏过程中的理化特性和贮藏特性进行了研究[10],并且也做了很多努力来揭示葡萄贮藏过程中维生素和多酚等营养成分的变化[11]。但是关于葡萄在低温贮藏期间的香气组成和含量变化研究还比较少,特别是针对大众喜爱的玫瑰香味的研究更少。成明[12]以‘玫瑰香’葡萄为试材的研究表明,冷库贮藏期间,葡萄的香气成分(醛类和醇类)随着贮藏期的延长,相对含量均呈下降趋势;主要物质(E)-2-己烯醛、里那醇、橙花醇的相对含量也均呈下降趋势。张鹏等[13]以‘无核寒香蜜’葡萄为试材,研究发现其主要挥发性成分乙酸乙酯、青叶醛、正己醇、叶醇等化合物在冷藏45 d后相对含量均低于冷藏15 d的果实。尽管MATSUMOTO和IKOMA[14]研究了不同采后贮藏对‘阳光玫瑰’葡萄果实中玫瑰香味和香气挥发物含量的影响,但也只研究了单一萜类化合物里那醇含量的变化。【本研究切入点】综上可见,葡萄果实在低温贮藏过程中会发生风味变化,但是仍然缺乏详细全面的特定代谢物类型和水平的信息。已有的研究也主要集中于游离态化合物检测,缺乏糖苷结合态香气化合物的代谢谱数据。【拟解决的关键问题】本研究以两个优新玫瑰香型葡萄品种‘瑞都红玫’和‘瑞都早红’为试材,探讨低温贮藏过程中游离态和糖苷结合态单萜组分和含量变化趋势,从更加全面的代谢物角度诠释玫瑰香气成分变化规律,为更好地研究贮藏期间葡萄风味品质的变化和最佳贮藏条件的建立提供理论参考。1 材料与方法

试验于2017年8—9月在北京市林业果树科学研究院进行。1.1 材料

供试鲜食葡萄品种为‘瑞都红玫’和‘瑞都早红’,两者均是北京市林业果树科学研究院育成的红色早中熟优新品种,选自‘京秀’和‘香妃’的杂交后代。果肉质地较脆,口味甜香,‘瑞都红玫’具有明显的玫瑰香味,‘瑞都早红’淡淡的玫瑰香味,成熟时可溶性固形物含量均可以达到16%以上[15,16]。试验植株为露地栽培7年生自根苗,定植于北京市林业果树科学院葡萄试验园内,单臂篱架水平龙干整形,株行距0.75 m×2 m,试验地土壤肥力中等,pH 6.9。采用简易避雨、地表园艺地布覆盖、滴灌供水和常规病虫害等管理模式,生长期内修剪及肥水管理一致。依据往年物候期记载结合可溶性固形物含量确定两个品种的成熟期进行样品采集,贮藏试验地点在北京市林业果树科学研究院冷库((2±1)℃,90% RH)。1.2 试验方法

选择颗粒饱满、果粒大小均匀、无病、无机械伤、无落粒的葡萄果穗放入开孔纸板箱,每箱5 kg。预冷至-1—0℃,放入PE葡萄保鲜膜中,封口入库。每个品种设3—5次重复,每隔15 d进行调查并取样测试相关指标。1.3 外观品质指标测定

失重率:穗重失重率(%)=(贮前穗重-贮后穗重)/贮前穗重×100。烂果率:烂果率(%)=(腐烂果粒的个数/果粒总数)×100。落粒率:落粒率(%)=落粒果重/总果重×100。果柄耐拉力:将葡萄果柄与弹簧秤相连,沿果粒纵轴方向拉至果柄从果实上脱离,记录弹簧秤最终读数,即为果柄耐拉力,每个处理重复10—20次以上,取平均值。果梗褐变指数:褐变指数(%)=∑(各级穗数×级数)/(最高级数×总穗数)×100;穗轴(果梗)褐变级别:无褐变的为0级,褐变0—1/4为1级,褐变1/4—1/2为2级,褐变1/2—3/4为3级,褐变3/4以上为4级。1.4 单萜化合物提取

单萜的提取和测定参考WEN等[17]的方法,略有改动。首先葡萄果实样品去除种子,以避免对挥发性化合物的提取产生任何可能的影响。其余果实部分(约50 g)在液氮中研磨,研磨过程中加入1 g PVPP和0.5 g D-葡萄糖酸内酯。得到的果粉样品在4℃低温静置4 h后,立即在4℃下以8 000×g离心10 min,得到澄清的葡萄汁。澄清葡萄汁直接检测游离单萜化合物。对每个样品进行3次独立提取。糖苷结合态化合物提取,固相萃取柱(Cleanert PEP-SPE柱,天津博纳艾杰尔公司)依次经10 mL甲醇和10 mL水活化后,加入2 mL上述澄清葡萄汁样品。经2 mL水洗脱去除一些糖、酸等低分子量的极性化合物后,加入5 mL二氯甲烷洗脱,进一步去除大部分游离态香气物质的干扰,最后用20 mL甲醇将结合态香气物质洗脱,收集至50 mL的圆底烧瓶内,整个固相萃取过程洗脱剂流速保持2 mL?min-1。所得甲醇洗脱液在旋转蒸发器下蒸发至干燥,然后重新溶解在10 mL的2 mol?L-1柠檬酸-磷酸盐缓冲溶液(pH 5.0)中。在40℃的培养箱中,用200 μL 糖苷酶AR 2000(100 mg?L-1,在pH 5.0的2 mol?L-1柠檬酸盐/磷酸盐缓冲液中)酶解结合型挥发性化合物16 h。每个果汁样品做2个独立的重复。

此后,在以下SPME条件下提取游离和结合态挥发物:将5 mL提取液与10 μL 4-甲基-2-戊醇(内标)和1 g NaCl混合在20 mL聚四氟乙烯硅隔膜盖小瓶中。将样品瓶在40℃下的500 r/min搅拌下平衡30 min。之后将活化的SPME针头(Supelco,Bellefonte,PA,USA)插入小瓶顶空,在40℃下吸附挥发性组分30 min。最后,将SPME针头插入GC进样口8 min,释放挥发物。

1.5 单萜化合物检测

气相色谱与质谱联用仪(GC-MS)型号:Agilent 7890B GC和Agilent 5977A MS(Agilent,美国)。毛细管柱为HP-INNOwax(60 m×0.25 mm×0.25 μm,J&W Scientific,美国)。GC-MS条件参考WU等[18]发表的方法:载气为高纯氦气(He,>99.999%),流速为1 mL?min-1;进样口温度为250℃,采样不分流模式,解析时间8 min;升温程序为50℃保持1 min,然后以3℃?min-1升温到220℃,保持5 min。质谱电离方式为EI,离子源温度为230℃,电离能为70 eV,四级杆温度为150℃,质谱接口温度为280℃,质量扫描范围为30—350 u。

1.6 单萜化合物定性定量分析

数据处理和分析通过ChemStation软件(安捷伦科技公司)进行,参考WU等[18]的方法。化合物首先根据标准品保留指数和质谱进行鉴定,当标准品不可用时,利用NIST 05标准库,参考标准品的保留指数和质谱匹配来鉴别。化合物定量使用标准曲线,每种标准品溶于甲醇,然后混合在一起。将混合标准溶液稀释,以获得每个分析物的5—12个浓度水平。对没有可用标准物的挥发物,使用具有相似碳原子或结构的标准物进行量化。1.7 数据处理与统计分析

数据统计分析利用分析软件SPSS 13.0,采用Duncan多重比较进行显著性分析,最低显著水平P<0.05;主成分分析和聚类分析采用MetaboAnalyst 4.0;绘图采用Excel和Sigma Plot 10.0。2 结果

2.1 两个葡萄品种低温贮藏过程中果实理化和贮藏特性变化

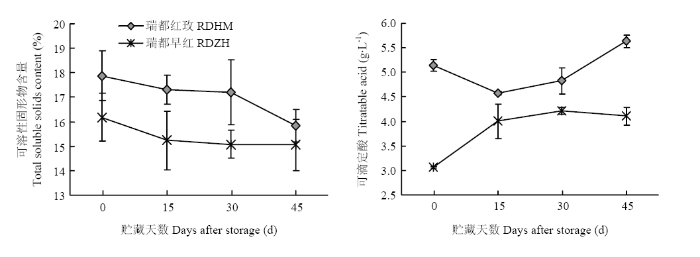

两个品种葡萄果实可溶性固形物含量在低温贮藏过程中均表现为逐渐降低的趋势,‘瑞都红玫’果实的可溶性固形物含量高于‘瑞都早红’(图1)。两个品种果实中可滴定酸含量在低温贮藏过程中变化趋势略有差异,‘瑞都红玫’中可滴定酸含量在贮藏15 d时有所下降,之后略有上升;而‘瑞都早红’可滴定酸含量在贮藏30 d内上升,之后在贮藏45 d时略有下降(图1)。‘瑞都红玫’果实中可滴定酸含量高于‘瑞都早红’。图1

新窗口打开|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT

新窗口打开|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT图1两种鲜食葡萄在低温贮藏过程中理化指标变化

Fig. 1The changes of physiochemical data of two grape varieties during storage at (2±1)℃

失重率、烂果率、落粒率、果柄耐拉力、果梗褐变指数等是评价果品耐贮性好坏、商品性优劣的直观表现。由表1可见,随着贮藏期的延长,两个品种的失重率均呈上升趋势,‘瑞都早红’在贮藏后期失重幅度增大,贮藏45 d时达到8.57%,‘瑞都红玫’失重率为5.46%。在低温贮藏过程中,‘瑞都红玫’的烂果率上升幅度较小。而‘瑞都早红’在贮藏早期烂果率较低(贮藏15 d时仅为1.96%),但贮藏中后期烂果现象比较明显。在整个贮藏过程中,‘瑞都红玫’落粒率均比较低,‘瑞都早红’落粒现象明显,到贮藏45 d达到50%。两个葡萄品种果柄耐拉力都随贮藏时间推移而降低,‘瑞都红玫’的果柄耐拉力高于‘瑞都早红’。两个品种在贮藏早期(15 d)果梗都没有发现褐变现象,30 d时都有不同程度的褐变发生,到贮藏45 d时,‘瑞都红玫’果梗褐变程度高于‘瑞都早红’。综合5项指标,‘瑞都红玫’的低温耐贮性优于‘瑞都早红’。

Table 1

表1

表1两种鲜食葡萄在低温贮藏过程中表观品质指标变化

Table 1

| 品种 Variety | 贮藏天数 Days after storage (d) | 失重率 Weight loss (%) | 果柄耐拉力 Berry retention force (N) | 烂果率 Percentage of decayed (%) | 落粒率 Berry drop ratio (%) | 果梗褐变指数 Browning index (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 瑞都红玫RDHM | 0 | 0 | 3.94±0.11 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 15 | 0.67±0.13 | 3.95±0.18 | 5.66±1.50 | 0 | 0 | |

| 30 | 2.15±0.80 | 4.49±0.22 | 9.26±1.654 | 14.04±2.22 | 30.00±2.10 | |

| 45 | 5.46±0.64 | 2.82±0.14 | 29.82±2.31 | 14.81±1.60 | 35.00±3.50 | |

| 瑞都早红RDZH | 0 | 0 | 3.62±0.37 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 15 | 1.39±0.37 | 4.04±0.16 | 1.96±0.96 | 4.84±1.40 | 0 | |

| 30 | 2.05±0.66 | 3.42±0.14 | 20.97±3.12 | 24.49±2.02 | 2.50±1.50 | |

| 45 | 8.57±0.90 | 2.06±0.21 | 77.38±8.42 | 50.00±13.54 | 35.00±3.00 |

新窗口打开|下载CSV

2.2 两个品种葡萄果实中的单萜化合物组分和含量比较

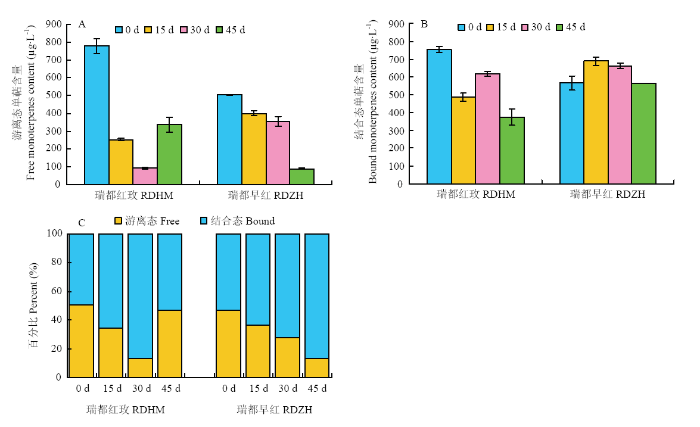

28种游离态单萜和糖苷结合态单萜在两个品种葡萄果实中均检测到,含量存在差异(表2、3)。在两个品种葡萄果实中,游离态单萜含量最高的6个化合物均是里那醇、β-月桂烯、β-cis-罗勒烯、柠檬烯、cis-呋喃型氧化里那醇和香叶醇。除了个别化合物如β-香茅醇、cis-氧化玫瑰和trans-呋喃型氧化里那醇,其余游离态单萜在‘瑞都红玫’中的含量均高于‘瑞都早红’(表2)。游离态单萜总量在‘瑞都红玫’中也明显高于‘瑞都早红’(图2)。Table 2

表2

表2低温贮藏过程中两种鲜食葡萄果实中游离态单萜含量变化

Table 2

| 编号 Code | 化合物 Compound | 品种 Variety | 贮藏天数Days after storage(d) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 15 | 30 | 45 | |||

| M1 | β-月桂烯 β-Myrcene | 瑞都红玫 RDHM | 72.62±1.79a | 29.98±1.07c | 10.10±2.19d | 35.39±0.64b |

| 瑞都早红 RDZH | 48.94±0.12a | 36.79±0.74b | 25.38±1.81c | 8.84±0.04d | ||

| M2 | 柠檬烯 Limonene | 瑞都红玫 RDHM | 30.66±1.24a | 11.71±0.50c | 7.40±0.12d | 24.2±0.32b |

| 瑞都早红 RDZH | 12.36±0.12c | 15.17±0.90a | 13.04±0.22b | 6.37±0.27d | ||

| M3 | 水芹烯 phellandrene | 瑞都红玫RDHM | 7.79±0.14a | 5.78±0.30bc | 1.87±0.08c | 6.07±0.03b |

| 瑞都早红 RDZH | 6.06±0.01a | 5.82±0.12b | 5.77±0.12c | 1.65±0.03d | ||

| M4 | β-trans-罗勒烯 β-trans-Ocimene | 瑞都红玫 RDHM | 19.74±0.84a | 7.33±0.30c | 3.83±0.03d | 12.45±0.01b |

| 瑞都早红RDZH | 9.98±0.07a | 9.58±0.37b | 8.98±0.31c | 3.11±0.02d | ||

| M5 | γ-松油烯 γ-Terpinen | 瑞都红玫 RDHM | 3.27±0.05a | 1.55±0.12b | 0.67±0.06c | 3.05±0.01a |

| 瑞都早红 RDZH | 1.81±0.10c | 2.44±0.18a | 2.10±0.01b | 0.52±0.01d | ||

| M6 | β-cis-罗勒烯 β-cis-Ocimene | 瑞都红玫 RDHM | 44.57±2.22a | 14.26±0.73c | 6.09±0.13d | 28.24±0.23b |

| 瑞都早红 RDZH | 19.69±0.19a | 19.75±0.92a | 13.09±0.72b | 4.52±0.02c | ||

| M7 | 异松油烯 Terpinolen | 瑞都红玫 RDHM | 9.87±0.43a | 4.75±0.14c | 3.88±0.41d | 8.84±0.06b |

| 瑞都早红 RDZH | 4.30±0.05c | 5.74±0.19b | 6.60±0.06a | 1.93±0.20d | ||

| M8 | cis-氧化玫瑰 cis Rose oxide | 瑞都红玫 RDHM | 0.20±0.01 | tr | tr | tr |

| 瑞都早红 RDZH | 0.38±0.03b | 0.72±0.03a | 0.73±0.04a | tr | ||

| M9 | trans-氧化玫瑰 trans-Rose oxide | 瑞都红玫 RDHM | tr | nd | nd | nd |

| 瑞都早红 RDZH | tr | tr | 0.43±0.07 | tr | ||

| M10 | 别罗勒烯 Allo-Ocimene | 瑞都红玫 RDHM | 16.13±0.64a | 5.76±0.26c | 3.28±0.05d | 10.41±0.66b |

| 瑞都早红 RDZH | 7.76±0.05a | 7.76±0.41a | 6.49±0.38b | 2.37±0.07c | ||

| M11 | (E,Z)-别罗勒烯 (E,Z)-Allo-Ocimene | 瑞都红玫 RDHM | 6.85±0.19a | 4.27±0.06c | 1.46±0.01d | 5.01±0.35b |

| 瑞都早红 RDZH | 4.92±0.04a | 4.70±0.12b | 4.33±0.13c | 0.90±0.01d | ||

| M12 | cis-呋喃型氧化里那醇 cis-furan linalool oxide | 瑞都红玫 RDHM | 25.02±1.17a | 12.55±0.26c | 2.61±0.07d | 11.23±2.07b |

| 瑞都早红 RDZH | 14.47±0.27c | 24.99±0.71a | 15.19±1.48b | 3.09±0.04c | ||

| M13 | trans-呋喃型氧化里那醇 trans-furan linalool oxide | 瑞都红玫 RDHM | 7.38±0.09a | 5.68±0.21b | 1.20±0.04c | 5.75±0.94b |

| 瑞都早红 RDZH | 7.56±0.30b | 9.19±0.13a | 8.68±1.03a | 2.51±0.06c | ||

| M14 | 橙花醚 Nerol oxide | 瑞都红玫 RDHM | 15.87±1.64b | 2.74±0.32c | 1.69±1.12d | 16.73±3.60a |

| 瑞都早红 RDZH | 3.43±0.37c | 15.44±2.20a | 15.18±1.43b | 1.98±0.13d | ||

| M15 | 香茅醛 Citronellal | 瑞都红玫 RDHM | 3.08±0.02a | 0.62±0.10c | 0.71±0.04c | 2.86±0.13b |

| 瑞都早红 RDZH | 1.10±0.03c | 1.37±0.03b | 1.86±0.03a | 0.34±0.04d | ||

| M16 | 里那醇 Linalool | 瑞都红玫 RDHM | 448.10±29.13a | 117.34±1.87b | 18.43±1.53c | 113.71±34.04b |

| 瑞都早红 RDZH | 317.18±1.10a | 199.00±7.22b | 186.07±37.64c | 28.51±0.60d | ||

| M17 | 4-松油烯醇 4-Terpineol | 瑞都红玫 RDHM | 2.73±0.04a | 0.61±0.08b | 0.24±0.02c | 2.65±0.05a |

| 瑞都早红 RDZH | 0.54±0.07c | 1.10±0.11b | 3.26±0.03a | 0.19±0.02d | ||

| M18 | 橙花醛 Neral | 瑞都红玫 RDHM | 0.83±0.04b | 0.67±0.03c | 1.20±0.08a | 0.54±0.08d |

| 瑞都早红 RDZH | 0.55±0.02c | 0.18±0.02d | 0.63±0.07b | 0.83±0.05a | ||

| M19 | α-衣兰油烯 α-muurolene | 瑞都红玫 RDHM | 0.33±0.01a | tr | 0.12±0.00c | 0.30±0.01b |

| 瑞都早红 RDZH | 0.27±0.01a | 0.13±0.01c | 0.18±0.01b | 0.10±0.01d | ||

| 续表2 Continued table 2 | ||||||

| 编号 Code | 化合物 Compound | 品种 Variety | 贮藏天数Days after storage(d) | |||

| 0 | 15 | 30 | 45 | |||

| M20 | α-萜品醇 α-Terpineol | 瑞都红玫 RDHM | 15.27±1.02a | 5.91±0.24c | 4.85±0.09d | 13.10±0.62b |

| 瑞都早红 RDZH | 4.97±0.06c | 7.46±0.36a | 6.42±1.22b | 4.48±0.05d | ||

| M21 | 香叶醛 geranial | 瑞都红玫 RDHM | 8.13±0.29a | 3.70±0.02d | 4.46±0.12c | 6.70±0.42b |

| 瑞都早红 RDZH | 6.94±0.21a | 4.99±0.10b | 3.77±0.28c | 3.32±0.04d | ||

| M22 | β-香茅醇 β-Citronellol | 瑞都红玫 RDHM | 3.82±0.03a | 3.58±0.01c | 1.41±0.05d | 3.67±0.02b |

| 瑞都早红 RDZH | 4.47±0.04a | 4.29±0.03b | 3.49±0.10c | 3.66±0.01d | ||

| M23 | γ-香叶醇 γ-geraniol | 瑞都红玫 RDHM | 1.61±0.01a | 0.42±0.01b | 0.47±0.01b | 1.55±0.01a |

| 瑞都早红 RDZH | 1.51±0.01a | 0.74±0.03c | 0.87±0.02b | 0.21±0.02d | ||

| M24 | 橙花醇 Nerol | 瑞都红玫 RDHM | 5.39±0.12a | 3.70±0.02c | 3.74±0.01c | 4.69±0.11b |

| 瑞都早红 RDZH | 4.13±0.01b | 4.14±0.04b | 4.60±0.16a | 1.76±0.11c | ||

| M25 | cis-异香叶醇 cis-isogeraniol | 瑞都红玫 RDHM | 0.17±0.01a | 0.15±0.01a | 0.16±0.01a | 0.17±0.01a |

| 瑞都早红 RDZH | 0.16±0.01a | 0.17±0.01a | 0.09±0.01b | tr | ||

| M26 | trans-异香叶醇 trans-isogeraniol | 瑞都红玫 RDHM | tr | tr | tr | nd |

| 瑞都早红 RDZH | tr | tr | tr | nd | ||

| M27 | 香叶醇 Geraniol | 瑞都红玫 RDHM | 23.67±0.68a | 10.72±0.06d | 12.63±0.05c | 16.08±0.85b |

| 瑞都早红 RDZH | 17.02±0.05a | 14.37±0.19b | 13.63±0.91b | 7.70±0.22c | ||

| M28 | 香叶酸 Geranic acid | 瑞都红玫 RDHM | 3.89±0.11a | 0.23±0.05c | 0.61±0.18b | 4.01±0.05a |

| 瑞都早红 RDZH | 2.74±1.73c | 4.22±0.26b | 4.74±0.03a | 0.34±0.30d | ||

新窗口打开|下载CSV

Table 3

表3

表3低温贮藏过程中两种鲜食葡萄果实中糖苷结合态单萜含量变化

Table 3

| 编号 Code | 化合物 Compound | 品种 Variety | 贮藏天数Days after storage (d) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 15 | 30 | 45 | |||

| CM1 | β-月桂烯 β-Myrcene | 瑞都红玫 RDHM | 104.17±3.62a | 66.87±6.59c | 87.94±4.74b | 53.44±0.70d |

| 瑞都早红 RDZH | 71.91±6.55a | 81.90±0.69b | 67.63±0.74c | 78.49±0.91d | ||

| CM2 | 柠檬烯 Limonene | 瑞都红玫 RDHM | 35.58±0.14a | 22.81±2.46c | 32.67±1.65b | 21.00±0.50d |

| 瑞都早红 RDZH | 28.28±2.87c | 37.00±0.12a | 33.91±0.49b | 27.44±0.22d | ||

| CM3 | 水芹烯 phellandrene | 瑞都红玫 RDHM | 21.63±0.45a | 12.69±1.74bc | 18.16±1.35b | 10.54±0.02d |

| 瑞都早红 RDZH | 15.25±1.41c | 18.37±0.26a | 15.61±0.19b | 15.91±0.02b | ||

| CM4 | β-trans-罗勒烯 β-trans-Ocimene | 瑞都红玫 RDHM | 29.91±0.65a | 19.52±1.88c | 27.09±1.87b | 17.66±0.74d |

| 瑞都早红 RDZH | 21.77±1.69c | 23.95±0.29a | 21.51±0.18c | 22.97±0.20b | ||

| CM5 | γ-松油烯 γ-Terpinen | 瑞都红玫 RDHM | 3.49±0.10a | 1.96±0.21c | 2.67±0.16b | 1.77±0.19d |

| 瑞都早红 RDZH | 2.42±0.20c | 3.06±0.06a | 2.75±0.03b | 2.35±0.02d | ||

| CM6 | β-cis-罗勒烯 β-cis-Ocimene | 瑞都红玫 RDHM | 49.82±1.26a | 29.78±3.29c | 43.87±2.66b | 24.85±3.11d |

| 瑞都早红 RDZH | 34.02±3.27c | 39.01±0.33a | 34.21±0.38c | 36.25±0.66b | ||

| CM7 | 异松油烯 Terpinolen | 瑞都红玫 RDHM | 9.39±0.21a | 3.23±0.38d | 5.35±0.36b | 3.81±0.58c |

| 瑞都早红 RDZH | 4.61±0.52c | 6.33±0.05b | 7.69±0.20a | 4.34±0.09c | ||

| CM8 | cis-氧化玫瑰 cis-Rose oxide | 瑞都红玫 RDHM | tr | tr | tr | tr |

| 瑞都早红 RDZH | 3.06±0.15c | 3.35±0.01b | 3.77±0.04a | 2.54±0.03d | ||

| 续表3 Continued table 3 | ||||||

| 编号 Code | 化合物 Compound | 品种 Variety | 贮藏天数Days after storage (d) | |||

| 0 | 15 | 30 | 45 | |||

| CM9 | trans-氧化玫瑰 trans-Rose oxide | 瑞都红玫 RDHM | tr | nd | nd | nd |

| 瑞都早红 RDZH | 2.89±0.02c | 2.97±0.02b | 3.03±0.01a | tr | ||

| CM10 | 别罗勒烯 Allo-Ocimene | 瑞都红玫 RDHM | 20.36±0.51a | 14.61±1.21c | 19.20±0.32b | 11.51±1.92d |

| 瑞都早红 RDZH | 16.38±1.06c | 17.93±0.10a | 16.15±0.03d | 17.03±0.15b | ||

| CM11 | (E,Z)-别罗勒烯 (E,Z)-Allo-Ocimene | 瑞都红玫 RDHM | 10.27±0.15a | 5.45±0.61c | 9.21±0.61b | 4.49±0.76d |

| 瑞都早红 RDZH | 6.83±1.04c | 8.23±0.04a | 6.35±0.12d | 7.43±0.05b | ||

| CM12 | cis-呋喃型氧化里那醇 cis-furan linalool oxide | 瑞都红玫 RDHM | 32.46±1.25a | 12.39±0.37d | 17.31±0.29b | 14.71±1.96c |

| 瑞都早红 RDZH | 31.09±1.09b | 51.48±3.39a | 66.26±5.82a | 28.75±0.73c | ||

| CM13 | trans-呋喃型氧化里那醇 trans-furan linalool oxide | 瑞都红玫 RDHM | 6.15±0.04a | 5.15±0.01d | 5.26±0.01c | 5.42±0.16b |

| 瑞都早红 RDZH | 5.77±0.11b | 6.50±0.21a | 8.27±0.61a | 5.58±0.06c | ||

| CM14 | 橙花醚 Nerol oxide | 瑞都红玫 RDHM | 40.48±1.11a | 18.96±1.54d | 26.04±0.81b | 19.30±3.26c |

| 瑞都早红 RDZH | 31.93±1.95c | 37.62±1.82b | 39.80±1.12a | 31.49±0.37c | ||

| CM15 | 香茅醛 Citronellal | 瑞都红玫 RDHM | 4.65±0.13b | 3.22±0.01c | 5.26±0.21a | 2.36±0.31d |

| 瑞都早红 RDZH | 3.97±0.31c | 4.27±0.19a | 2.62±0.07d | 4.19±0.38b | ||

| CM16 | 里那醇 Linalool | 瑞都红玫 RDHM | 170.62±3.37a | 85.49±3.52b | 76.27±0.74c | 68.43±13.08d |

| 瑞都早红 RDZH | 79.89±4.25c | 123.71±3.55b | 140.54±4.86a | 62.86±0.93d | ||

| CM17 | 4-松油烯醇 4-Terpineol | 瑞都红玫 RDHM | 1.00±0.01a | 0.47±0.01c | 0.72±0.07b | 0.70±0.05b |

| 瑞都早红 RDZH | 0.72±0.01b | 0.76±0.01b | 0.92±0.03a | 0.61±0.05c | ||

| CM18 | 橙花醛 Neral | 瑞都红玫 RDHM | 19.16±0.67b | 19.89±0.04b | 24.73±0.92a | 5.79±1.46c |

| 瑞都早红 RDZH | 22.79±0.05c | 23.09±3.22b | 23.61±0.27b | 26.43±0.68a | ||

| CM19 | α-衣兰油烯 α-muurolene | 瑞都红玫 RDHM | 0.92±0.01a | 0.74±0.01b | 0.98±0.00a | 0.59±0.06c |

| 瑞都早红 RDZH | 0.98±0.03a | 0.98±0.04a | 0.94±0.01c | 0.96±0.01b | ||

| CM20 | α-萜品醇 α-Terpineol | 瑞都红玫 RDHM | 22.75±0.08a | 5.25±0.36c | 21.57±0.05a | 14.17±5.62b |

| 瑞都早红 RDZH | 14.09±1.47c | 21.75±0.09b | 22.44±0.03a | 6.30±0.32d | ||

| CM21 | 香叶醛 Geranial | 瑞都红玫 RDHM | 57.75±0.08b | 54.82±0.10c | 67.55±2.05a | 29.45±3.76d |

| 瑞都早红 RDZH | 51.72±0.23c | 56.79±5.86b | 51.57±0.91c | 60.27±0.09a | ||

| CM22 | β-香茅醇 β-Citronellol | 瑞都红玫 RDHM | 7.29±0.22a | 5.75±0.49b | 7.19±0.23a | 2.95±0.64c |

| 瑞都早红 RDZH | 19.41±0.12b | 19.83±0.07a | 19.22±0.07c | 19.07±0.04d | ||

| CM23 | γ-香叶醇 γ-geraniol | 瑞都红玫 RDHM | 7.63±0.05a | 3.35±0.03b | 7.61±0.04a | 1.83±0.39c |

| 瑞都早红 RDZH | 5.59±2.73b | 7.57±0.03a | 2.62±0.09c | 7.54±0.01a | ||

| CM24 | 橙花醇 Nerol | 瑞都红玫 RDHM | 20.77±0.24b | 20.22±0.23b | 21.82±0.14a | 17.83±0.33c |

| 瑞都早红 RDZH | 22.46±0.24b | 23.96±0.26a | 19.79±0.07d | 20.94±0.15c | ||

| CM25 | cis-异香叶醇 cis-isogeraniol | 瑞都红玫 RDHM | 0.85±0.02a | 0.80±0.01b | 0.80±0.01b | tr |

| 瑞都早红 RDZH | 0.82±0.02b | 0.86±0.01a | tr | 0.86±0.01a | ||

| CM26 | trans-异香叶醇 trans-isogeraniol | 瑞都红玫 RDHM | 0.78±0.01b | 0.81±0.01a | 0.81±0.01a | nd |

| 瑞都早红 RDZH | tr | tr | tr | nd | ||

| CM27 | 香叶醇 Geraniol | 瑞都红玫 RDHM | 74.25±2.45b | 66.16±1.66c | 84.83±2.22a | 42.11±3.66d |

| 瑞都早红 RDZH | 64.09±2.65b | 63.96±2.21c | 45.40±0.17d | 71.37±0.05a | ||

| CM28 | 香叶酸 Geranic acid | 瑞都红玫 RDHM | 0.42±0.11d | 2.42±0.04a | 1.80±0.28b | 0.85±0.12c |

| 瑞都早红 RDZH | 3.44±2.44b | 3.03±1.49c | 4.57±2.55a | 2.87±0.13d | ||

新窗口打开|下载CSV

图2

新窗口打开|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT

新窗口打开|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT图2低温贮藏过程中两个葡萄品种游离态和糖苷结合态单萜总量变化

Fig. 2Changes of total free and glycosidically-bound monoterpenes content in two grape varieties during storage at (2±1)℃

两个品种葡萄果实中糖苷结合态单萜含量较高的6个化合物依次是里那醇、β-月桂烯、香叶醇、香叶醛、β-cis-罗勒烯和橙花醚。这些主成分化合物在‘瑞都红玫’果实中含量高于‘瑞都早红’,而氧化玫瑰、香茅醇和橙花醇等糖苷结合态单萜的含量在 ‘瑞都早红’中较高(表3)。但是结合态单萜总量仍表现为‘瑞都红玫’高于‘瑞都早红’(图2)。

关于不同形式单萜含量高低比较,本研究发现在所检测的28种单萜中,除了里那醇、异松油烯、氧化玫瑰、trans-呋喃型氧化里那醇、4-松油烯醇和香叶酸6种化合物的糖苷结合态含量在‘瑞都红玫’果实中低于游离态,其余单萜糖苷结合态含量均高于游离态(表2、3)。但是总糖苷结合态单萜含量略低于游离态(图2);而在‘瑞都早红’果实中,除了里那醇,其余27种单萜糖苷结合态含量均高于游离态(表2、3),总糖苷结合态单萜含量高于游离态(图2)。

2.3 低温贮藏过程中‘瑞都红玫’果实中单萜化合物变化

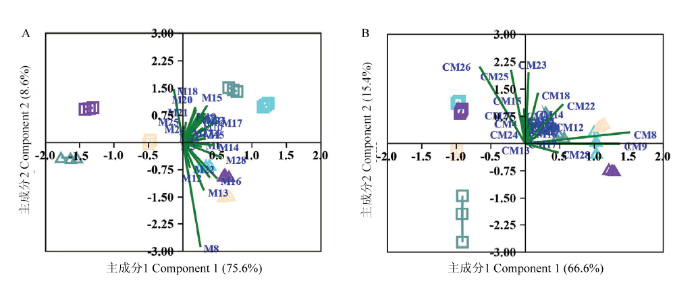

在整个低温贮藏过程中,‘瑞都红玫’果实中主要游离态单萜成分略有波动。贮藏初期(15 d)变化不大,主要游离态单萜为里那醇、β-月桂烯、β-cis-罗勒烯、cis-呋喃型氧化里那醇、柠檬烯和香叶醇;到贮藏30 d时,‘瑞都红玫’果实中含量最高的6个化合物依次为里那醇、香叶醇、β-月桂烯、柠檬烯、β-cis-罗勒烯和α-萜品醇;贮藏45 d时,α-萜品醇含量降低而橙花醚含量升高成为主含量单萜。在整个低温贮藏过程中,里那醇含量均最高。28种游离态单萜含量在贮藏初期(15 d)均呈现下降趋势;在贮藏30 d后,包含里那醇在内的大部分单萜含量持续下降,而香叶醇、香叶酸、橙花醇、香叶醛、香茅醛和橙花醛等单萜含量略有上升;贮藏后期(45 d),除了橙花醛,其他27种单萜含量表现上升趋势(表2)。聚类分析结果显示,在低温贮藏过程中,‘瑞都红玫’果实中游离态单萜含量变化趋势主要聚为4类(图3-A)。第一类包含β-月桂烯(M1)、水芹烯(M3)、(E, Z)-别罗勒烯(M11)、cis-呋喃型氧化里那醇(M12)、trans-呋喃型氧化里那醇(M13)、里那醇(M16)和β-香茅醇(M22),这一类单萜在低温贮藏过程中含量持续降低,到贮藏30 d时达到最低,贮藏后期略有上升。第二类变化趋势与第一类相近,不同的是这类化合物在低温贮藏15 d后含量急剧下降,到贮藏中期(30 d)降至最低,贮藏45 d时含量明显升高,这类化合物包含柠檬烯(M2)、β-trans-罗勒烯(M4)、γ-松油烯(M5)、β-cis-罗勒烯(M6)、异松油烯(M7)、别罗勒烯(M10)、4-松油烯醇(M17)和α-萜品醇(M20)。第三类有cis-氧化玫瑰(M8)、香茅醛(M15)、橙花醇(M24)、香叶醇(M27)和香叶酸(M28)等单萜,这类单萜在贮藏初期(15 d)含量即降为最低,贮藏中后期含量上升,贮藏45 d时含量明显升高。第四类仅包含橙花醛(M18),尽管M18在贮藏初期含量也略有下降,但是与前3类不同,该单萜在贮藏30 d时含量最高,贮藏45 d时含量最低。

图3

新窗口打开|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT

新窗口打开|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT图3低温贮藏过程中‘瑞都红玫’中游离态和糖苷结合态单萜化合物含量变化

A:游离态;B:结合态

Fig. 3Changes of free and glycosidically-bound monoterpenes content in Ruidu Hongmei during storage at (2±1)℃

A: Free; B: Bound

在低温贮藏过程中,主要糖苷结合态单萜组分差异不明显,主要包括里那醇、β-月桂烯、香叶醇、香叶醛和β-cis-罗勒烯等单萜。在贮藏30 d时,β-月桂烯和香叶醇含量升高,高于结合态里那醇含量(表3)。大部分结合态单萜变化趋势相似,贮藏初期(15 d)表现下降,中期(30 d)又有所上升,贮藏后期(45 d)急剧下降(表3)。聚类分析显示结合态单萜在低温贮藏过程中变化趋势也主要聚为4类(图3-B):第一类有β-月桂烯(CM1)、柠檬烯(CM2)、水芹烯(CM3)、β-trans-罗勒烯(CM4)、γ-松油烯(CM5)、β-cis-罗勒烯(CM6)、别罗勒烯(CM10)、(E, Z)-别罗勒烯(CM11)、香茅醛(CM15)、α-衣兰油烯(CM19)和γ-香叶醇(CM23),这类糖苷结合态单萜在贮藏15 d时含量显著下降,之后上升,到贮藏45 d又急剧下降到最低含量。第二类结合态单萜包含异松油烯(CM7)、cis-呋喃型氧化里那醇(CM12)、trans-呋喃型氧化里那醇(CM13)、橙花醚(CM14)、里那醇(CM16)、4-松油烯醇(CM17)和α-萜品醇(CM20),这类单萜在低温贮藏过程中含量持续降低,没有明显的升高过程。第三类结合态单萜在贮藏早期含量降低不明显,在贮藏30 d时略有上升,到后期(45 d)急剧降到最低,这类单萜包含橙花醛(CM18)、香叶醛(CM21)、β-香茅醇(CM22)、橙花醇(CM24)、cis-异香叶醇(CM25)和香叶醇(M27)。最后一类仅包含香叶酸(CM28),在贮藏15 d时含量升高,之后逐渐降低。

在低温贮藏过程中,‘瑞都红玫’果实中游离态单萜总量呈现先下降后期略有升高的趋势,游离态单萜占总单萜的比例也表现为先下降后期升高的趋势(图2)。而糖苷结合态单萜总量在贮藏初期(15 d)下降,贮藏30 d后又升高,之后又略有下降(图2)。贮藏15 d后,糖苷结合态单萜含量高于游离态单萜含量。

2.4 低温贮藏过程中‘瑞都早红’果实中单萜化合物变化

在低温贮藏过程中,‘瑞都早红’果实中主要游离态单萜化合物组分改变不大。里那醇含量最高,其次是β-月桂烯,其他化合物含量高低略有变化(表2)。大多数游离态单萜含量在低温贮藏过程中呈现下降的趋势。聚类分析结果显示(图4-A),游离态单萜变化趋势主要聚为4类:第一类包含β-月桂烯(M1)、β-cis-罗勒烯(M6)、别罗勒烯(M10)、(E, Z)-别罗勒烯(M11)、里那醇(M16)、α-衣兰油烯(M19)、香叶醛(M21)、β-香茅醇(M22)、γ-香叶醇(M23)和香叶醇(M27),这类单萜含量在低温贮藏过程中逐渐降低,到贮藏45 d降到最低。第二类单萜有柠檬烯(M2)、水芹烯(M3)、β-trans-罗勒烯(M4)、γ-松油烯(M5)、异松油烯(M7)、cis-氧化玫瑰(M8)、cis-呋喃型氧化里那醇(M12)、trans-呋喃型氧化里那醇(M13)、香茅醛(M15)、橙花醇(M24)和香叶酸(M28),这类化合物在贮藏早、中期含量上升,贮藏后期急剧下降,降到最低。第三类包含4种单萜trans-氧化玫瑰(M9)、橙花醚(M14)、4-松油烯醇(M17)和α-萜品醇(M20),它们的含量在贮藏15 d或者贮藏30 d显著升高,之后下降。第四类单萜仅包含橙花醛(M18)一种化合物,该化合物在贮藏15 d含量显著下降,之后逐渐升高。

图4

新窗口打开|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT

新窗口打开|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT图4低温贮藏过程中‘瑞都早红’中游离态和糖苷结合态单萜化合物含量变化

A:游离态;B:结合态

Fig. 4Changes of free and glycosidically-bound monoterpenes content in Ruidu Zaohong during storage at (2±1)℃

A: Free; B: Bound

在低温贮藏前期和中期,‘瑞都早红’果实中主要糖苷结合态单萜组分基本没有变化,含量最高的化合物是里那醇,其次是β-月桂烯和香叶醇等单萜。到贮藏后期(45 d),里那醇含量下降,β-月桂烯和香叶醇含量升高,分别成为第一、二主含量单萜(表3)。低温贮藏过程中糖苷结合态单萜含量变化趋势主要聚为两大类(图4-B):第一类包含β-月桂烯(CM1)、水芹烯(CM3)、β-trans-罗勒烯(CM4)、β-cis-罗勒烯(CM6)、别罗勒烯(CM10)、(E, Z)-别罗勒烯(CM11)、香茅醛(CM15)、γ-香叶醇(CM23)、cis-异香叶醇(CM25)、香叶醇(M27);橙花醛(CM18)、香叶醛(CM21)、α-衣兰油烯(CM19)、β-香茅醇(CM22)、橙花醇(CM24)、cis-异香叶醇(CM25)等单萜,这类化合物在贮藏15 d时升高,之后下降,到贮藏45 d含量又有所回升。第二类单萜主要有cis-氧化玫瑰(CM8)、trans-氧化玫瑰(CM9)、里那醇(CM16)、4-松油烯醇(CM17)、α-萜品醇(CM20)、异松油烯(CM7)、cis-呋喃型氧化里那醇(CM12)、trans-呋喃型氧化里那醇(CM13)、橙花醚(CM14)、香叶酸(CM28)、柠檬烯(CM2)、和γ-松油烯(CM5)等,这类糖苷结合态单萜在贮藏前中期含量呈上升趋势,到贮藏45 d时显著下降。

在低温贮藏过程中,‘瑞都早红’果实中游离态单萜总量表现为逐渐降低的趋势,到贮藏45 d降到最低,仅为89.26 μg?L-1;糖苷结合态单萜总量在贮藏初期(15 d)升高,贮藏30 d后逐渐降低(图2)。整个贮藏期间,游离态单萜占总单萜的比例逐渐降低,而糖苷结合态比例上升(图2)。

2.5 低温贮藏过程中两个葡萄品种单萜化合物主成分分析

以不同贮藏时期2个葡萄品种游离态单萜定量数据进行PCA分析(图5-A),从数据中提取了两个主成分,主成分1(PC1)和主成分2(PC2)分别解释了75.6%和8.6%的变量信息,这两个主成分占据了所有数据84.2%的变异,反映了化合物的绝大部分信息。在PC1方向,不同贮藏时间样品可以得到很好地区分,贮藏初期(0 d)和后期(45 d)的‘瑞都红玫’样品位于第一象限,贮藏15 d和30 d样品位于第二象限;而‘瑞都早红’在贮藏后期(45 d)与其他时期明显区分开,位于第三象限。除了橙花醛(M18),其他游离态单萜含量与PC1均呈正相关。由图5-A可见,对于PC1,香叶酸(M28)、橙花醚(M14)、里那醇(M16)、4-松油烯醇(M17)、cis-呋喃型氧化里那醇(M12)和β-cis-罗勒烯(M6)等单萜载荷值较高,这些化合物在贮藏开始(0 d)和后期(45 d)的‘瑞都红玫’样品中含量显著高于贮藏15 d和30 d的样品(表2);在贮藏后期(45 d)‘瑞都早红’样品中的含量明显低于其他3个时期样品(表2)。这些单萜可以作为区分贮藏时期样品的主要贡献差异化合物成分。在PC2方向,两个葡萄品种明显区分开,‘瑞都红玫’样品位于第一、二象限,而‘瑞都早红’位于第三、四象限。在PC2中,cis-氧化玫瑰(M8)、橙花醛(M18)和trans-呋喃型氧化里那醇(M13)等游离态单萜载荷绝对值最高,其中M8和M13与PC2呈负相关。‘瑞都早红’中这两个单萜含量明显高于‘瑞都红玫’,而M18的含量低于‘瑞都红玫’。这3个游离态单萜可以作为两个品种区分的主要差异化合物。图5

新窗口打开|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT

新窗口打开|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT图5低温贮藏过程中两个葡萄品种游离态和糖苷结合态单萜变化主成分分析

方块代表‘瑞都红玫’;三角代表‘瑞都早红’;水蓝色表示贮藏后0 d;橘黄色表示贮藏后15 d;紫色表示贮藏后30 d;蓝绿色表示贮藏后45 d

Fig. 5PCA analysis of total free and glycosidically-bound monoterpenes content in two grape varieties during storage at (2±1)℃

Square represent Ruidu Hongmei; Triangle represent Ruidu Zaohong; Aqua blue indicate 0 days after storage; Bisque indicate 15 days after storage; Blueviolet indicate 30 days after storage; Cadetblue indicate 45 days after storage

以2个葡萄品种不同贮藏时间糖苷结合态单萜定量数据进行PCA分析(图5-B),从数据中也提取了两个主成分,分别解释了66.6%(PC1)和15.4%(PC2)的变量信息。根据PC1可以把两个葡萄品种进行很好的区分,‘瑞都红玫’样品位于第二、三象限,而‘瑞都早红’样品主要位于第一、四象限。在PC1中,cis-氧化玫瑰(CM8)、trans-氧化玫瑰(CM9)、trans-异香叶醇(CM26)和β-香茅醇(CM22)等单萜载荷值较大,可以作为品种区分的主要差异物。根据PC2成分,两个品种不同贮藏时期样品也可以区分,‘瑞都红玫’贮藏0 d和30 d样品位于第二象限,而贮藏15 d和45 d样品位于第三象限;‘瑞都早红’贮藏30 d样品明显远离其他时期样品。在PC2中,trans-异香叶醇(CM26)、γ-香叶醇(CM23)、cis-异香叶醇(CM25)和橙花醛(CM18)可以作为主要差异成分。

3 讨论

单萜是葡萄果实中重要的异戊二烯衍生物,是玫瑰香型葡萄的典型香气成分。研究表明,影响香气成分积累的因素很多除了采前因素外,采后保鲜贮藏也会引起香气的变化[6]。本研究发现两个不同品种果实中,尽管各个单萜含量存在显著差异,但是主含量化合物成分相似。在‘瑞都红玫’和‘瑞都早红’果实中,主要高含量游离态单萜有里那醇、β-月桂烯、柠檬烯和香叶醇等化合物,这与孙磊等[19]研究结果一致。这种单萜组分上的相似性可能是因为‘瑞都红玫’和‘瑞都早红’均是从‘京秀’和‘香妃’杂交后代中选出的优新品种,它们具有相似的遗传背景[15,16]。此外,‘瑞都红玫’中游离态单萜含量高于‘瑞都早红’,孙磊等[19]也在‘瑞都红玫’中检测到高于‘瑞都早红’的单萜含量,感官品尝‘瑞都红玫’的玫瑰香味比‘瑞都早红’更加浓郁。尽管两者游离态单萜总量远远低于玫瑰香型酿酒葡萄被定义的浓度范围(≥6 mg?L-1)[4],但这两个葡萄品种均具有不同程度的玫瑰香味,说明鲜食葡萄可能存在不同的化合物浓度范围。RUIZ-GARCíA等[20]的研究表明,葡萄果实玫瑰香味与氧化玫瑰的有无相关,在所有玫瑰香型葡萄品种中都存在氧化玫瑰,而非玫瑰香型葡萄中都不存在氧化玫瑰,本研究在两个品种中均检测到不同浓度的游离态氧化玫瑰(表2)。之前的一些研究表明玫瑰香型葡萄品种富含萜烯类化合物,这些化合物在葡萄果实中主要以糖苷结合态形式存在,这些结合态萜类作为潜在的香味来源具有重要意义[21,22]。本研究首次对两个品种葡萄果实中糖苷结合态单萜进行了定性定量分析,发现在两个葡萄品种中大部分糖苷结合态单萜含量明显高于游离态,说明单萜在这两种葡萄果实中也主要以结合态形式存在。两个葡萄品种果实中高含量糖苷结合态单萜组分相似,含有里那醇、β-月桂烯和香叶醇等,这与上述游离态结果相似。FENOLL等[23]在‘玫瑰香’葡萄果实中也检测到高含量的糖苷结合态里那醇和香叶醇,此外,香茅醇和橙花醇含量也较高,与本研究结果略有不同。成熟的‘阳光玫瑰’果实中也检测到高含量的里那醇和香叶醇,但是并未检测到β-月桂烯[24]。此外,之前的研究表明酿酒葡萄果实中糖苷结合态香气物质含量是游离态的2—8倍[25],但是本研究发现在鲜食葡萄果实中存在不同的组成比例,这可能与葡萄品种、果实成熟度和栽培模式等有关。甚至在‘瑞都红玫’果实中,里那醇、异松油烯和氧化玫瑰等6种单萜游离态含量高于结合态含量,而高含量的游离态单萜更容易被感知,从而增强香味的浓郁程度。WU等[24]在鲜食葡萄‘阳光玫瑰’果实中也检测到较高含量的游离态异松油烯、氧化玫瑰和脱氢芳樟醇等单萜。

低温贮藏过程中,‘瑞都红玫’和‘瑞都早红’中的大部分游离态单萜或早或晚出现含量降低的趋势。之前的研究指出低温贮藏是能够最大限度保持葡萄果实品质的有效技术,但是随着贮藏时间的延长,可能会导致果实香味改变或香味丧失[26,27]。贮藏温度和时间会对挥发性香气成分产生显著影响[28,29,30]。单萜化合物含量之间存在较高的相关性[31],本研究中同一类化合物变化趋势相似。β-月桂烯、里那醇和cis-呋喃氧化里那醇等聚为一类;氧化玫瑰、香叶醇和香叶酸等聚为一类;而异油松烯和α-萜品醇等单萜聚在一起,这与酿酒葡萄果实发育过程中各个单萜聚类结果相似[5],可能与同一类单萜具有相同或者相近的合成代谢途径相关[3]。但是各个游离态单萜在两个品种中的变化趋势不尽相同,如主含量单萜里那醇、β-月桂烯和β-香茅醇(M22)等在两个品种中虽然都聚在第一类,但在‘瑞都红玫’中贮藏30 d时含量降为最低,在45 d时含量又有所回升;‘瑞都早红’则在45 d降为最低。橙花醇(M24)和香叶醇(M27)等化合物在‘瑞都红玫’中贮藏15 d时含量即降为最低,之后含量又逐渐升高,而在‘瑞都红玫’中贮藏15 d时含量升高,之后随着贮藏时间延长而逐渐降低;cis-氧化玫瑰(M8)在两个品种中也表现不同的变化趋势,这些差异可能与两个品种具有不同的低温耐贮性相关。MORALES等[32]也发现不同品种树莓在低温贮藏过程中,里那醇、香叶醇和α-萜品醇等游离态单萜存在相反的变化模式。在不同品种柑橘低温贮藏过程中,单萜也呈现不同的变化趋势[33]。28种游离态单萜在两个品种低温贮藏过程中的变化有特性也有共性。主成分分析结果显示两个品种葡萄中香叶酸(M28)、橙花醚(M14)、里那醇(M16)和4-松油烯醇(M17)等游离态单萜在低温贮藏过程中含量差异明显,在PC1中具有高的荷载值,这些游离态单萜可以作为区分不同贮藏时间样品的主要贡献单萜成分。

糖苷结合态单萜低温贮藏过程中的变化模式与游离态单萜表现不同,其中总糖苷结合态单萜的含量和比例与游离态单萜呈现相反的趋势,这可能是因为在低温贮藏过程中糖苷结合态和游离态单萜之间发生了相互转化。MATSUMOTO和IKOMA[14]指出采后贮藏过程中贮藏温度和时间可能影响萜类化学或酶水解反应,导致各种单萜含量波动差异。糖苷结合态单萜在‘瑞都红玫’中变化趋势聚为4类,在‘瑞都早红’则聚为两大类。LI等[5]在两种不同酿酒葡萄中也发现不同的结合态单萜聚类模式,可能与不同品种中单萜糖基转移酶活性差异有关。随着低温贮藏时间延长,包含高含量单萜里那醇、β-月桂烯和香叶醇等各个糖苷结合态单萜呈现不同的变化趋势,表现出品种特异性。说明相较于贮藏条件,品种对于糖苷结合态单萜影响更大。随后的主成分分析进一步印证了这一结果,在PC1方向上两个品种可以进行很好的区分。RUIZ-GARCíA等[20]的研究曾指出氧化玫瑰可以作为品种有无玫瑰香味的标记物。本研究也发现在PC1中,糖苷结合态cis-氧化玫瑰和trans-氧化玫瑰都具有较高的荷载值,说明该化合物也可以作为区分两个品种的主要标记物。

4 结论

‘瑞都红玫’的低温耐贮性优于‘瑞都早红’。两个鲜食葡萄品种中的主含量单萜化合物组分相近,主要游离态单萜包含有里那醇、β-月桂烯、β-cis-罗勒烯、柠檬烯、cis-呋喃型氧化里那醇和香叶醇等;主要糖苷结合态单萜包括里那醇、β-月桂烯、香叶醇、香叶醛、β-cis-罗勒烯和橙花醚等。‘瑞都红玫’中单萜含量高于‘瑞都早红’。在低温贮藏过程中,游离态单萜含量呈现动态变化过程,主要呈现4种变化模式;相较于低温贮藏初期,大部分游离态单萜单萜含量呈现降低趋势。香叶酸(M28)、橙花醚(M14)、里那醇(M16)和4-松油烯醇(M17)等游离态单萜可以作为不同贮藏时间样品区分的主要贡献单萜成分。在贮藏过程中,总糖苷结合态单萜的含量与游离态单萜呈现相反的趋势,各个糖苷结合态单萜的变化趋势因品种而不同。氧化玫瑰可以作为区分两个品种的主要标记物。参考文献 原文顺序

文献年度倒序

文中引用次数倒序

被引期刊影响因子

URLPMID:30814549 [本文引用: 1]

URLPMID:31645942 [本文引用: 1]

URL [本文引用: 2]

Monoterpene compounds are a kind of typical aroma components in grapes and wine,with both free and bound forms. This review focuses on progress of monoterpene biosynthesis pathway and the key enzyme-monoterpene synthase in grapes,classification of monoterpene compounds as well as the structure,content,research methodology of glycosidically conjugated monoterpenes in grapes and wine. Also,the prospect of monoterpenes research is suggested.

URL [本文引用: 2]

Monoterpene compounds are a kind of typical aroma components in grapes and wine,with both free and bound forms. This review focuses on progress of monoterpene biosynthesis pathway and the key enzyme-monoterpene synthase in grapes,classification of monoterpene compounds as well as the structure,content,research methodology of glycosidically conjugated monoterpenes in grapes and wine. Also,the prospect of monoterpenes research is suggested.

[本文引用: 2]

[本文引用: 3]

URLPMID:23852166 [本文引用: 2]

[本文引用: 1]

URL [本文引用: 1]

URL [本文引用: 1]

DOI:10.1016/j.postharvbio.2013.10.001URL [本文引用: 1]

[本文引用: 1]

DOI:10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.03.055URLPMID:23790850 [本文引用: 1]

Flavonoids and stilbenes are secondary metabolites produced in plants that can play an important health-promoting role. The biosynthesis of these compounds generally increases as a response to biotic or abiotic stress; therefore, in order to achieve as high phenolic accumulation as possible, the interactive effects of storage conditions (temperature and time) and UV-C radiation on polyphenols content in postharvest Redglobe table grape variety were investigated. During a storage time longer than 48h, both cold storage (4 degrees C) and UV-C exposure of almost 3min (2.4kJm(-2)) positively enhanced the content of cis- and trans-piceid (34 and 90mugg(-1) of skin, respectively) together with quercetin-3-O-galactoside and quercetin-3-O-glucoside (15 and 140mugg(-1) of skin, respectively) up to three fold respect to control grape samples. Conversely, catechin was not significantly affected by irradiation and storage treatments. With regard anthocyanins, the highest concentrations of cyanidin-3-O-glucoside and peonidin-3-Oglucoside were observed in Redglobe, stored at both room temperature and 4 degrees C, after 5min (4.1kJm(-2)) of UV-C treatment and 24h of storage. Gathered findings showed that combined postharvest treatments can lead to possible

[D].

[本文引用: 1]

[D].

[本文引用: 1]

DOI:10.1111/jfds.1972.37.issue-2URL [本文引用: 1]

DOI:10.1111/jfds.1972.37.issue-2URL [本文引用: 1]

[本文引用: 2]

[本文引用: 2]

[本文引用: 2]

[本文引用: 2]

[本文引用: 2]

URLPMID:26444528 [本文引用: 1]

[本文引用: 2]

DOI:10.16420/j.issn.0513-353x.2016-0164URL [本文引用: 2]

‘Ruidu Xiangyu’,‘Ruidu Hongmei’,‘Ruidu Zaohong’,‘Ruidu Hongyu’,‘Ruidu

Cuixia’and their parents‘Jingxiu’,‘Xiangfei’were used as materials. Headspace solid phase

micro-extraction(HS-SPME)and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry(GC–MS)combined with

automated Mass Spectral Deconvolution and Identification System(AMDIS)were employed to analyzethe free terpene contents in the seven varieties,to explicate their flavor characteristics. The results showed

that a total of 29 terpenes were identified,but the concentration varied among different varieties. The total

terpene concentration in‘Xiangfei’and‘Ruidu Xiangyu’was over 1 000 μg · L-1,while‘Ruidu Hongmei’,

‘Ruidu Zaohong’and‘Ruidu Hongyu’had similar concentration,the terpene in‘Ruidu Cuixia’and

‘Jingxiu’were both lower than 50 μg · L-1.‘Xiangfei’and‘Ruidu Xiangyu’had the highest OAVs,

the OAVs in‘Ruidu Cuixia’and‘Jingxiu’were less than 1,these results roughly corresponded to the

multiple years sensory analysis data. As principal component analysis(PCA)results showed that,the

cumulative variance contribution ratio of the first two principal components is 84.79%. The representative

variables of the first principal component include (E,Z)-alloocimene, (Z)-alloocimene ,linalool,

(E)-β-ocimene,(Z)-β-ocimene,limonene,terpinolene,cis-rose oxide,trans-rose oxide and β-myrcene,

and the representative ones of the second principal component have geraniol,geranial,γ-geraniol,neral

and trans-furan linalool oxide. Floral and fruity are the most prominent aroma characteristics of these free

terpenes,in which linalool,limonene,cis-rose oxide and trans-rose oxide contributing to the floral aroma,

while linalool,limonene,geraniol having fruity aroma.

DOI:10.16420/j.issn.0513-353x.2016-0164URL [本文引用: 2]

‘Ruidu Xiangyu’,‘Ruidu Hongmei’,‘Ruidu Zaohong’,‘Ruidu Hongyu’,‘Ruidu

Cuixia’and their parents‘Jingxiu’,‘Xiangfei’were used as materials. Headspace solid phase

micro-extraction(HS-SPME)and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry(GC–MS)combined with

automated Mass Spectral Deconvolution and Identification System(AMDIS)were employed to analyzethe free terpene contents in the seven varieties,to explicate their flavor characteristics. The results showed

that a total of 29 terpenes were identified,but the concentration varied among different varieties. The total

terpene concentration in‘Xiangfei’and‘Ruidu Xiangyu’was over 1 000 μg · L-1,while‘Ruidu Hongmei’,

‘Ruidu Zaohong’and‘Ruidu Hongyu’had similar concentration,the terpene in‘Ruidu Cuixia’and

‘Jingxiu’were both lower than 50 μg · L-1.‘Xiangfei’and‘Ruidu Xiangyu’had the highest OAVs,

the OAVs in‘Ruidu Cuixia’and‘Jingxiu’were less than 1,these results roughly corresponded to the

multiple years sensory analysis data. As principal component analysis(PCA)results showed that,the

cumulative variance contribution ratio of the first two principal components is 84.79%. The representative

variables of the first principal component include (E,Z)-alloocimene, (Z)-alloocimene ,linalool,

(E)-β-ocimene,(Z)-β-ocimene,limonene,terpinolene,cis-rose oxide,trans-rose oxide and β-myrcene,

and the representative ones of the second principal component have geraniol,geranial,γ-geraniol,neral

and trans-furan linalool oxide. Floral and fruity are the most prominent aroma characteristics of these free

terpenes,in which linalool,limonene,cis-rose oxide and trans-rose oxide contributing to the floral aroma,

while linalool,limonene,geraniol having fruity aroma.

DOI:10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.01.005URLPMID:24518327 [本文引用: 2]

Aroma is an important quality characteristic in Muscat grapes and constitutes a major concern for viticulturist and grapevine breeders. For this reason, Muscat aroma variability was characterised in a segregating progeny and in a collection of table grapes, to assess the usefulness of the presence or absence of rose oxide for predicting Muscat genotypes. Simple tasting and an analysis of free and bound aroma compounds, including rose oxide, linalool oxide, linalool, alpha-terpineol, citronellol, nerol, geraniol, benzyl alcohol and 2-phenylethanol, were carried out. The association between Muscat score and the compounds considered as active odorants according to their odour activity values was also evaluated. The results obtained pointed to a highly significant correlation between the presence/absence of rose oxide in grapes and the presence/absence of Muscat aroma. Thus, this analysis could be a useful tool for identifying Muscat cultivars in a more objective way than sensory analysis. (C) 2014 Elsevier Ltd.

URLPMID:27374521 [本文引用: 1]

DOI:10.1007/s00425-012-1704-0URLPMID:22824963 [本文引用: 1]

In developing grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.) berries, precursor volatile organic compounds (PVOCs) are largely stored as glycosides which may be hydrolyzed to release VOCs during fruit ripening, wine making, or aging. VOCs can be further transformed by yeast metabolism. Together, these processes contribute to complexity of wine aromas. Floral and citrus odors of many white wine varietals are attributed to monoterpenes and monoterpene alcohols, while phenolic compounds, norisoprenoids, and other volatiles also play important roles in determining aroma. We present an analysis of PVOCs stored as glycosides in developing Gewurztraminer berries during the growing season. We optimized a method for PVOC analysis suitable for small amounts of Muscat grapevine berries and showed that the amount of PVOCs dramatically increased during and after veraison. Transcript profiling of the same berry samples underscored the involvement of terpenoid pathway genes in the accumulation of PVOCs. The onset of monoterpenol PVOC accumulation in developing grapes was correlated with an increase of transcript abundances of early terpenoid pathway enzymes. Transcripts encoding the methylerythritol phosphate pathway gene 4-hydroxy-3-methylbut-2-enyl diphosphate reductase, as well as geraniol diphosphate synthase, were up-regulated preceding and during the increase in monoterpenol PVOCs. Transcripts for linalool/nerolidol synthase increased in later veraison stages.

DOI:10.1016/j.foodchem.2008.09.060URL [本文引用: 1]

DOI:10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.125778URLPMID:31704071 [本文引用: 2]

This study investigated the evolution of both free and bound volatile compounds in 'Shine Muscat' grape from post-fruit set to post-maturity and limiting factors of the lipoxygenase (LOX) pathway. C6 compounds and terpenes were the main free and bound volatile compounds, respectively. At pre-softening, volatile compounds concentrations were mainly regulated by expansion dilution, and terpene concentrations decreased significantly, which resulted in the minimum terpene concentrations occurred at softening. The volatile compounds were mainly regulated by metabolic synthesis at post-softening, and the production of C6 compounds, terpenes and esters largely began at 10, 12weeks post-flowering and maturity stages, respectively. In the LOX pathway, LOX, alcohol dehydrogenase and the substrate alcohols were the limiting factors. The aroma maturity stages occurred at 15.4weeks post-flowering. Finally, the developmental patterns of the volatile compounds in grape were summarized considering previous results in neutral and non-Muscat aromatic varieties.

[本文引用: 1]

DOI:10.1016/j.postharvbio.2010.09.011URL [本文引用: 1]

Mandarins are very prone to losing flavor quality during storage and, as a result, often have a short shelf life. To better understand the basis of this flavor loss, two mandarin varieties ('W. Murcott' and 'Owari') were stored for 0, 3 and 6 weeks at either 0 degrees C, 4 degrees C, or 8 degrees C plus 1 week at 20 degrees C, and then evaluated for sensory attributes as well as quality parameters and aroma volatile profile. The experiment was conducted multiple times for each variety over two seasons, using three separate grower lots per experiment. Flavor quality was reduced in 'Owari' following 4 weeks of storage as off-flavor increased, while for 'W. Murcott' the hedonic score decreased after the fruit were stored for 7 weeks. Sensory panelists also noted a decline in tartness during storage for both varieties that was associated with an increase in the ratio of soluble solids concentration (SSC) to titratable acidity (TA). Large increases in alcohols and esters occurred during storage in both varieties, a number of which were present in concentrations in excess of their odor threshold values and are likely contributing to the loss in flavor quality. Thirteen aroma volatiles, consisting mainly of terpenes and aldehydes, declined during storage by up to 73% in 'Owari', only one of which significantly changed in 'W. Murcott'. Although many of these volatiles had aromas characteristic of citrus, their involvement in flavor loss during storage is unclear. 'W. Murcott' stored at 8 degrees C had slightly superior flavor to fruit stored at either 0 degrees C or 4 degrees C, and the better flavor was associated with higher SSC/TA and lesser tartness. Aroma volatiles did not play a role in the temperature effect on flavor as there were no significant differences in volatile concentrations among the three temperatures. There was no effect of storage temperature on the flavor of 'Owari'. Published by Elsevier B.V.

DOI:10.1016/j.postharvbio.2013.02.013URL [本文引用: 1]

Mandarin flavor quality often declines during storage but the respective contributions to the flavor disorder of warm versus cold temperature during storage were unknown. To determine this 'W. Murcott Afourer' mandarins were stored for either 6 weeks at a continuous 5 degrees C or held at 20 degrees C for either 1 or 2 weeks following, 2 or 4 weeks of 5 degrees C storage. Sensory quality as measured by likeability was maintained throughout the 6 week storage when the fruit were kept at 5 degrees C, but rapidly declined upon moving fruit to 20 degrees C. Flavor loss increased as the duration of cold storage prior to the warm temperature holding period was lengthened. The beneficial effect of maintaining mandarins in cold storage was also observed in three of the five other varieties where there was flavor quality loss during storage at a warmer temperature. Soluble solids concentration (SSC) and titratable acidity (TA) were relatively unchanged by holding. at 20 degrees C, but aroma volatiles, with alcohols and ethyl esters being of the greatest importance, were greatly enhanced in concentration and are the likely cause of the off-flavor. The increases in aroma volatile concentration were apparent within one day of holding the fruit at 20 degrees C, indicating the need to carefully control postharvest storage temperatures. A comparison of 5,10 and 20 degrees C holding indicated that it is only at 20 degrees C that aroma volatiles contributing to off-flavor accumulated. This study suggests that it may be possible in many mandarin varieties to prevent losses in flavor quality by maintaining the fruit at a cold temperature (5-10 degrees C) following packing and until the time of consumption. Published by Elsevier B.V.

DOI:10.1016/j.postharvbio.2010.09.012URL [本文引用: 1]

Melting flesh peach (Prunus persica L Batsch., cv. Hujingmilu) fruit were harvested and stored at 0, 5, 8 degrees C for up to 21 d. Data on emission of characteristic aroma-related volatiles, and expression patterns of related genes, including lipoxygenase (LOX), hydroperoxide lyase (HPL), alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH), and alcohol acyltransferase (AAT), were obtained from fruit at the different low temperatures for 7, 14 and 21 d and a subsequent shelf-life for 3 cl after each of those storage times. Production of volatiles was markedly influenced by storage temperature and time. In general, fruit at 5 degrees C were sensitive to chilling injury (CI) and had the lowest levels of volatile compounds, especially fruity note vo'latiles such as esters and lactones. An electronic nose (e-nose) was used to evaluate peach aroma, and the Cl fruit could be separated from those at low temperature but which had not developed the disorder. Relative expression levels of genes involved in the LOX pathway were repressed in fruit with Cl. Of the LOX family genes, PpLOX1 and PpLOX3 were upregulated in association with accumulated ethylene during shelf-life, while levels of PpLOX2 and PpLOX4 declined after removal. Expression of PpHPL1, PpADH1, FpADH2, and PpADH3 exhibited similar decreasing patterns during shelf-life, whereas transcript levels of PpAAT1 were induced. The results suggest that reduced levels of fruity note volatiles in fruit with Cl were the consequence of modifications in expression of PpLOX1. PpLOX3 and PpAAT1; the significance of ethylene in relation to aroma-related volatiles production after cold storage is discussed. (C) 2010 Elsevier B.V.

DOI:10.1016/j.postharvbio.2018.08.015URL [本文引用: 1]

[本文引用: 1]

URLPMID:27746799 [本文引用: 1]

DOI:10.1016/j.postharvbio.2014.05.013URL [本文引用: 1]

In this study, the effect of storage time at low temperature on volatile compounds in two cultivars of raspberry, Rubus idaeus L. cv. Sevillana and Maravilla, was determined. A total of 28 compounds were identified in both cultivars and showed quantitative differences between the cultivars. The Sevillana cultivar was richer in volatile compounds than the Maravilla cultivar. beta-Ionone had the highest concentration in both cultivars. We observed opposing trends in the volatile compound composition for the cultivars during storage at low temperature, in which 'Sevillana' lost compounds and 'Maravilla' was enriched. Therefore, storage at low temperature causes important changes in the volatile compound profile of raspberry, particularly the Sevillana cultivar, with significant decreases in C-13-norisoprenoids and increases in terpenes. These changes are most likely responsible for the aromatic differences between the cultivars because of the presence of terpenes in 'Sevillana' and C-13-norisoprenoids in 'Maravilla'. (C) 2014 Elsevier B.V.

DOI:10.1016/j.postharvbio.2011.07.009URL [本文引用: 1]

Mandarins suffer from short 'flavor-life' compared with other citrus species. The recommended minimum safe temperature for mandarin storage is 5-8 degrees C. However, because of continuing reductions in permitted chemical residues and increasing concern regarding decay development, mandarins are often shipped at much lower temperatures of 3-4 degrees C. In the last few years we noticed wide differences in responsiveness of mandarin varieties to chilling, and that the earliest indication of damage was a decrease in flavor acceptability. In the present study, we evaluated changes in flavor and quality of chilling-tolerant 'Or' and chilling-sensitive 'Odem' mandarins after 4 weeks of storage at 2, 5, or 8 degrees C followed by 3 days at 20 degrees C. Low storage temperatures resulted in loss of orange peel color in fruit of both varieties, which became paler and yellowish. The flavor of 'Or' mandarins was not affected by different storage temperatures, whereas 'Odem' showed severe flavor loss at low storage temperatures. GC-MS analysis of aroma volatiles revealed that changes of storage temperatures had no major effects on aroma volatile contents in 'Or' mandarins. However, in 'Odem' mandarins, storage at 2 degrees C caused accumulation of 13 volatiles, mainly terpenes and their derivates, whereas storage at 8 degrees C resulted in decreases of six volatiles, comprising five terpenes and one terpene derivative. Overall, we conclude that storage temperature is a fundamental factor affecting color and flavor of mandarins, and therefore it is crucial to define the optimal minimum safe temperature for each mandarin variety. Furthermore, massive accumulation of terpenes is most likely the cause for the decrease in flavor acceptability of 'Odem' mandarins after storage at low chilling temperatures. (C) 2011 Elsevier B.V.