1. 中国科学院沈阳应用生态研究所 污染生态与环境工程重点实验室,辽宁 沈阳 110016;

2. 中国科学院大学,北京 100049

收稿日期:2021-03-15;接收日期:2021-05-11;网络出版时间:2021-09-01

基金项目:国家自然科学基金(Nos. 41907220, 41977295, 41907287),中国科学院前沿科学重点研究计划(No. ZDBS-LY-DQC038),辽宁省兴辽英才计划(No. XLYC1807139) 资助

作者简介:李秀颖?? 中国科学院沈阳应用生态研究所助理研究员,博士就读于中国科学院生态环境研究中心环境化学与生态毒理学国家重点实验室。现从事有机氯代污染物的微生物厌氧降解研究,注重有机卤呼吸细菌的分离与功能挖掘,有机卤呼吸细菌和辅助菌株协同降解与修复有机氯污染研究。曾在Environmental Science and Technology、Microbiology Resource Announcements等期刊发表论文多篇.

摘要:脱卤单胞菌Dehalogenimonas是绿弯菌门(Chloroflexi) 脱卤球菌纲(Dehalococcoidia) 的一个属。脱卤单胞菌属目前包含Dehalogenimonas lykanthroporepellens、Dehalogenimonas alkenigignens和Dehalogenimonas formicexedens这3个已正式命名的物种,其成员均为严格厌氧的专性有机卤呼吸细菌,利用氢气和甲酸作为电子供体,以氯代烷烃(例如1, 2, 3-三氯丙烷、1, 2-二氯丙烷和1, 2-二氯乙烷) 作为电子受体,通过介导还原性脱氯反应获得能量进行生长。我国污染场地地下水中氯代烷烃等有机氯污染较为突出,脱卤单胞菌的产能方式使其在污染场地原位修复中具有重要的应用价值。新近发现的WBC-2菌株和“Candidatus Dehalogenimonas etheniformans” GP菌株可以脱氯降解某些氯代烯烃,其中GP菌株能够将一氯乙烯完全脱氯至乙烯,拓展了有限的一氯乙烯脱氯菌种资源,丰富了脱卤单胞菌的生态学功能。文中围绕脱卤单胞菌属的生理生化特性、生态功能及基因组信息进行综述,旨在为污染场地有机氯污染物的清理及工程实施提供理论指导。

关键词:脱卤单胞菌有机卤呼吸还原脱氯生物修复

Advances of using Dehalogenimonas in anaerobic degradation of chlorinated compounds and bioremediation of contaminated sites

Yiru Cui1,2, Yi Yang1, Jun Yan1, Xiuying Li1

1. Key Laboratory of Pollution Ecology and Environmental Engineering, Institute of Applied Ecology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Shenyang 110016, Liaoning, China;

2. University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China

Received: March 15, 2021; Accepted: May 11, 2021; Published: September 1, 2021

Supported by: National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 41907220, 41977295, 41907287), Key Research Program of Frontier Science of Chinese Academy of Sciences (No. ZDBS-LY-DQC038), Talent Research Foundation to Invigorate Liaoning of Liaoning Province, China (No. XLYC1807139)

Corresponding author: Xiuying Li. Tel: +86-24-83970426; Fax: +86-24-83970300; E-mail: lixiuying@iae.ac.cn.

Abstract: The genus Dehalogenimonas (Dhgm) is a recently discovered taxonomic group within the class Dehalococcoidia of the phylum Chloroflexi. To date, Dhgm consists of three formally described species including Dehalogenimonas lykanthroporepellens, Dehalogenimonas alkenigignens and Dehalogenimonas formicexedens. All isolates of these three Dhgm species are obligate organohalide-respiring bacteria. They use hydrogen and formate as electron donors and chlorinated ethanes (e.g., 1, 2, 3-trichloropropane, 1, 2-dichloropropane, 1, 2-dichloroethane) as electron acceptors in energy-conserving reductive dechlorination reaction. Chlorinated ethanes are common groundwater contaminants in China. The unique metabolic capacities of Dhgm strains implicate it may play important roles in site remediation. The recently reported Dhgm sp. strain WBC-2 and 'Candidatus Dehalogenimonas etheniformans' strain GP are capable of dechlorinating certain chlorinated ethenes. More importantly, strain GP can completely detoxify the carcinogenic vinyl chloride (VC) to ethene. These findings expand the diversity of microorganisms involved in the respiratory VC reductive dechlorination and improve the understanding of Dhgm's ecological functions. Here, we summarize the advances in physiological and biochemical characteristics, ecological functions and genomic features of Dhgm, with the aim to develop effective and sustainable strategies to facilitate the bioremediation of chlorinated compounds contaminated sites.

Keywords: Dehalogenimonasorganohalide respirationreductive dechlorinationbioremediation

20世纪70年代,有机氯化物对环境的持久性污染和对人类健康的潜在危害引起人们的持续关注,其生物降解途径和机制现已得到广泛而深入的研究。有机氯化物C-Cl键的断裂主要由脱卤酶系统主导,包括由水解脱卤酶、氧解脱卤酶和还原性脱卤酶催化的3种反应机制。然而,氯取代基引起化合物电负性的改变限制了水解脱卤和氧解脱卤的作用,以致多氯取代化合物通过这两种机制断裂C-Cl键非常困难。另一方面,许多受有机氯化物污染的含水层和沉积层属于厌氧环境,厌氧条件下的还原脱氯过程显得尤为重要。早期关于微生物还原脱氯的研究表明这一降解过程缓慢且不彻底,并主要通过共代谢途径完成。直到Desulfomonile tiedjei[1]的发现开启了人们对脱氯细菌这一类微生物以及还原脱氯降解机制的新认识,随后不断有新的脱氯细菌种属被发现和报道,包括脱卤拟球菌属Dehalococcoides[2-3]、脱亚硫酸菌属Desulfitobacterium[4]、脱卤杆菌属Dehalobacter[5]、脱卤单胞菌属Dehalogenimonas[6-7]等,它们广泛分布于海洋、陆地等各类不同的自然环境中。这一类脱氯细菌以有机氯化合物作为电子受体,以氢气、甲酸或者乙酸作为电子供体,通过还原性脱卤酶催化,以氢原子取代卤素基团的还原脱氯反应获得生长所需的能量。类比硝酸盐呼吸、硫酸盐呼吸等厌氧条件下微生物获得能量的方式,这一过程被称为“有机卤呼吸” (Organohalide respiration),而这类脱氯细菌又被称为有机卤呼吸细菌(Organohalide-respiring bacteria)。根据有机卤呼吸是否为脱氯细菌唯一的能量代谢方式,可以将已被分离的菌株分为兼性和专性有机卤呼吸细菌[8]。虽然还原性脱氯反应在热力学上理论产能较高,但以有机卤呼吸获得能量的细胞实际生长产率较低。研究表明,在未污染环境中专性有机卤呼吸细菌在微生物群落中占比不高[8-9]。

有机卤呼吸细菌对地下水、沉积物等厌氧环境中有机氯化合物的去除具有重要作用,如脱卤拟球菌能够优先控制污染物三氯乙烯和一氯乙烯完全脱氯转化为无毒无害的乙烯[2]。围绕脱卤拟球菌的生理生化特征、还原性脱卤酶功能多样性的研究广泛而深入,以脱卤拟球菌为核心菌株开发的KB-1、SDC-9等微生物菌剂已有很多修复地下水有机氯污染的应用实例,对氯代烯烃和氯代烷烃均有比较理想的降解效果,显示了有机卤呼吸细菌在污染场地修复中的重要价值和潜力[10-12]。脱卤单胞菌是近年来发现的新型专性有机卤呼吸细菌,与脱卤拟球菌同属于绿弯菌门(Chloroflexi) 下的脱卤球菌纲(Dehalococcoidia),二者的16S rRNA基因序列相似性约为90%,但与绿弯菌门内其他属的进化距离较远[13-14]。许多脱卤单胞菌菌株通过二卤消除反应进行有机卤呼吸,近年来发现的该属中的新成员可以介导氢解脱氯反应(每步脱氯反应以一个质子置换一个氯离子) 并降解包括一氯乙烯在内的多种氯代烯烃[15-16]。这些研究结果拓展了对于脱卤单胞菌在生态功能和有机氯污染治理领域的认识。鉴于目前对于脱卤单胞菌的生理生化特性、降解功能以及分子机制的研究还不够系统和深入,本文总结了脱卤单胞菌的分离、生理生化特征、对有机氯化物的降解能力以及基因组特征等方面的研究进展,为将脱卤单胞菌应用于污染场地修复提供参考。

1 脱卤单胞菌的发现及分离脱卤单胞菌属目前包含3个已正式命名的种,Dehalogenimonas lykanthroporepellens[7]、Dehalogenimonas alkenigignens[17]以及Dehalogenimonas formicexedens[18],这3个物种的模式菌株均分离自受有机氯化物污染的一个美国超级基金场地(Superfund site) 的地下水。其中,D. lykanthroporepellens BL-DC-9是第一株纯培养下的脱卤单胞菌菌株,也是首个被报道的能够还原脱氯1, 2, 3-三氯丙烷的有机卤呼吸细菌。除以上3个正式命名的种,Manchester等在1, 1, 2, 2-四氯乙烷脱氯降解富集培养物中发现能够对反式-1, 2-二氯乙烯进行还原脱氯的菌株Dehalogenimonas sp. WBC-2[15]。此外,新近报道的“Candidatus Dehalogenimonas etheniformans” GP菌株是Yang等通过富集培养德国斯图加特附近罗滕贝格葡萄酒产区没有受有机氯污染的葡萄渣堆肥中的微生物而发现,随后由吕燕等分离获得[14, 16]。目前,所有的脱卤单胞菌菌株均是在厌氧条件下,通过在液体培养基中进行连续梯度稀释以获得接近单细胞培养物的绝迹稀释法(Dilution-to-extinction) 而分离[6, 14, 17-18]。将液体培养基中分离的菌株接种至用琼脂配制的固体培养基,即使经过2个月的培养也无法形成可见的菌落,表明其无法在固体表面生长[6, 17-18]。脱卤单胞菌的分离主要以氯代烷烃作为电子受体,如D. lykanthroporepellens BL-DC-9、D. lykanthroporepellens BL-DC-8以1, 2, 3-三氯丙烷,D. alkenigignens IP3-3、D. alkenigignens SBP-1和D. formicexedens NSZ-14菌株以1, 2-二氯丙烷进行绝迹稀释分离[6, 17-18]。此外,吕燕等以1, 1-二氯乙烯为电子受体分离出“Candidatus Dehalogenimonas etheniformans” GP菌株,是目前唯一1株以氯代烯烃类化合物为电子受体分离出的脱卤单胞菌[14]。虽然WBC-2菌株也是通过降解氯代烯烃被发现,但是目前尚未被分离。菌株生长所用的液体培养基包含无机盐、维生素和微量矿物质等常规成分,以乙酸和氢气分别作为碳源和电子供体。在稀释分离过程中常常加入氨苄青霉素和万古霉素等抗生素以抑制其他微生物的生长。为了维持较低的氧化还原电位,液体培养基中还需要添加柠檬酸钛(Ⅲ)、硫化钠等还原剂,随后研究发现,添加柠檬酸钛(Ⅲ) 作为还原剂的培养基比以硫化钠和L-半胱氨酸作为还原剂的培养基更适合脱卤单胞菌生长[17]。

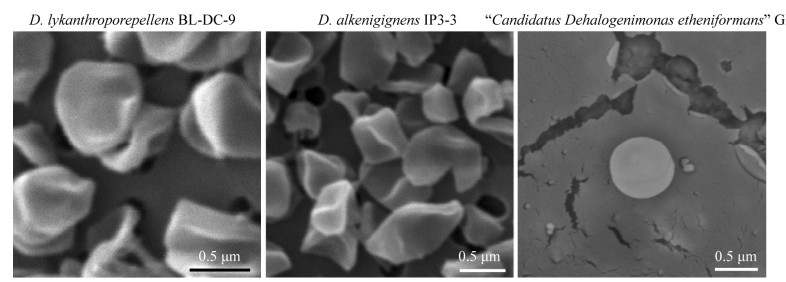

2 脱卤单胞菌的生理生化特征与功能脱卤单胞菌细胞呈微小的不规则球形,直径约为0.3–1.1 μm (图 1),无运动性,不能形成孢子,革兰氏染色呈阴性,耐受高浓度氨苄青霉素(例如1.0 g/L) 和万古霉素(例如0.1 g/L),最适生长温度为30 ℃[6-7, 14, 17-18]。D. lykanthroporepellens和D. alkenigignens已分离菌株可以生长的pH范围是6.0–8.0,D. formicexedens NSZ-14菌株可以生长的pH范围是5.5–7.5[7, 17-18]。另外,D. lykanthroporepellens BL-DC-9菌株可耐受高达2% (W/V) 的NaCl盐度,而D. formicexedens NSZ-14菌株和D. alkenigignens IP3-3菌株可分别在NaCl盐度0.1%和1%的培养基中生长,当NaCl浓度达到2%时无法生长[7, 17-18]。不同种间的脱卤单胞菌的胞内脂肪酸成分存在一定差异,但主要成分类似。D. lykanthroporepellens BL-DC-9胞内主要脂肪酸按含量由高到低依次为C18:1ω9c > C16:1ω9c > C16:0 > C14:0;D. alkenigignens IP3-3为C18:1ω9c > C16:0 > C14:0 > C16:1ω9c;D. formicexedens NSZ-14为C18:1ω9c > C14:0 > C16:0[7, 17-18]。

|

| 图 1 脱卤单胞菌的扫描电镜图片[14, 20-21] Fig. 1 Scanning electron microscopy images of several Dehalogenimonas isolates[14, 20-21]. Bar scale=0.5 μm. |

| 图选项 |

脱卤单胞菌已正式命名的3个种均能对多种C2-C3氯代烷烃进行还原脱氯,包括1, 2, 3-三氯丙烷、1, 2-二氯丙烷、1, 1, 2, 2-四氯乙烷、1, 1, 2-三氯乙烷和1, 2-二氯乙烷。它们介导的还原脱氯反应为二卤消除,即在相邻碳原子上去除两个卤素基团并同时形成碳-碳双键,可将1, 2-二氯乙烷和1, 2-二氯丙烷分别转化为无毒的终产物乙烯和丙烯,将1, 1, 2-三氯乙烷转化为一氯乙烯、1, 1, 2, 2-四氯乙烷转化为二氯乙烯、1, 2, 3-三氯丙烷转化为烯丙基氯[7, 17-18]。脱卤单胞菌在利用不同有机氯化物时显示出一定的偏好性,当培养体系中同时存在1, 1, 2-三氯乙烷、1, 2-二氯乙烷和1, 2-二氯丙烷时,D. lykanthroporepellens BL-DC-9菌株和D. alkenigignens IP3-3菌株均先利用1, 1, 2-三氯乙烷进行还原脱氯,待1, 1, 2-三氯乙烷浓度较低时才开始降解另外2种氯代烷烃[19]。这3个种的脱卤单胞菌菌株不能利用仅含有1个氯取代基的氯代烷烃类(如1-氯丙烷、2-氯丙烷)、一个碳原子上有多个氯取代基但相邻碳原子上无氯取代基的氯代烷烃类(如1, 1-二氯乙烷、1, 1, 1-三氯乙烷) 以及氯代甲烷类(如二氯甲烷、三氯甲烷、四氯化碳) 有机氯。已分离的脱卤单胞菌菌株只能以氢气和甲酸盐作为电子供体。乙酸盐、丙酸盐、丁酸盐、乳酸盐、丙酮酸盐、果糖、葡萄糖、乳糖、甲醇、乙醇、甲乙酮、柠檬酸盐、富马酸盐、苹果酸盐、琥珀酸盐或酵母提取物都不能单独作为电子供体支持其生长[7, 17-18]。

脱卤单胞菌菌株对含除氯以外其他卤素(如氟、溴)取代基化合物的脱卤还原研究还很有限,已有研究表明,D. lykanthroporepellens BL-DC-9菌株可以将1, 2-二溴乙烷、1, 2-二溴丙烷分别还原脱卤为乙烯和丙烯,同时释放出无机溴离子[22]。越来越多的证据表明,脱卤单胞菌除了能以二卤消除方式进行还原脱卤反应,还具有其他代谢和系统发育多样性,且可以通过氢解的方式降解其他类型的有机氯化物。例如,Manchester等报道了富集培养物WBC-2中1株新型脱卤单胞菌(GenBank登录号:JQ599651) 通过将反式-1, 2-二氯乙烯还原脱氯为一氯乙烯的过程进行自身生长,其16S rRNA基因序列与D. lykanthroporepellen. BL-DC-9菌株和D. alkenigignens IP3-3菌株分别有96.6%和96.5%的相似性[15]。Leitner等通过单体同位素分析技术发现富集培养物中的未知脱卤单胞菌参与四氯乙烯脱氯还原到乙烯的过程[23]。Yang等在没有受到有机氯污染的葡萄渣堆肥中发现并分离1株可以脱氯降解一氯乙烯等多种氯乙烯的新型脱卤单胞菌“Candidatus Dehalogenimonas etheniformans” GP菌株[16]。这一发现尤其值得关注,以往只有脱卤拟球菌属的一些菌株才能将生物毒性极强的一氯乙烯完全还原至乙烯。除一氯乙烯外,GP菌株还能够将三氯乙烯的氯取代基逐个脱除,生成二氯乙烯和一氯乙烯,最后完全脱氯至无毒的乙烯[24-25]。脱卤单胞菌还可以进行氯代苯的还原脱氯,Wang等通过分析可对多氯联苯混合物Aroclor 1260进行脱氯的富集培养物发现,Aroclor 1260发生脱氯降解的同时其中的脱卤单胞菌CG3菌株的16S rRNA基因(GenBank登录号:JQ990328) 拷贝显著增加,这为脱卤单胞菌也可以参与多氯联苯的脱氯提供了有力证据。在Qiao等建立的可将1, 2, 4-三氯代苯脱氯降解为苯的富集培养体系中,新型脱卤单胞菌可能是对1, 2, 4-三氯代苯和1, 2-/1, 3-二氯代苯异构体进行脱氯还原降解的主要菌株[26]。从以上研究可以看出,脱卤单胞菌对氯代脂肪烃和氯代芳香烃均具有脱氯功能,其分离纯化工作有待进一步开展,以更加深入研究其代谢及功能的多样性,扩大其生态功能的范畴。

3 脱卤单胞菌基因组特征及脱卤酶以来自绿弯菌门(Chloroflexi)、厚壁菌门(Firmicutes) 及变形菌门(Proteobacteria)的31株典型有机卤呼吸细菌和脱卤单胞菌进行基于16S rRNA基因序列的系统发育分析。使用MEGA X软件中MUSCLE算法对比多个16S rRNA基因序列,neighbour-joining方法构建系统发育树,并以jukes-cantor分析(1 000次重复) 校正[27-30],结果如图 2所示。脱卤单胞菌属与同样来自绿弯菌门脱卤球菌纲的脱卤拟球菌属及多氯联苯降解菌“Dehalobium chlorocoercia” DF-1菌株[31]进化距离较近,脱卤单胞菌各菌株与Dehalococcoides mccartyi 195菌株的相似性为90%–91%;与非绿弯菌门其他属的有机卤呼吸细菌的进化距离均较远,序列相似性低于75%。

|

| 图 2 基于16S rRNA基因序列的脱卤单胞菌系统发育树 Fig. 2 Phylogenetic comparison based on 16S rRNA gene sequences of strains from Dehalogenimonas and representative organohalide-respiring bacteria from the phyla Firmicutes, Chloroflexi and Proteobacteria. Numbers in parentheses: GenBank accession number; Numbers in branch points: branch support values; Bar length=0.05: nucleotide divergence between sequences. |

| 图选项 |

脱卤单胞菌基因组高度精简,大部分的管家基因只有一个拷贝。D. lykanthroporepellens BL-DC-9菌株、D. alkenigignens IP3-3菌株、. D. alkenigignens BRE15M菌株、D. formicexedens NSZ-14菌株、“Candidatus Dehalogenimonas etheniformans” GP菌株及Dehalogenimonas sp. WBC-2菌株[18, 20-21, 32-34] 6个已经完成测序的菌株基因组基本信息如表 1所示。脱卤单胞菌的环状染色体长度为1.65–2.09 Mbp,不含质粒,基因组G+C含量为49.0–56.3 mol%,这些数据略大于脱卤拟球菌的基因组(基因组大小为1.27–1.52 Mb,G+C含量46.9–48.9 mol%[35])。D. lykanthroporepellens BC-DL-9、D. alkenigignens IP3-3、D. formicexedens NSZ-14、“Candidatus Dehalogenimonas etheniformans” GP菌株的基因组都包含至少47个tRNA基因,包含编码所有20种常见氨基酸和不常见氨基酸硒代半胱氨酸的密码子及单拷贝的5S、16S、23S rRNA基因。从脱卤单胞菌中鉴定出的基因组特异性基因包括编码转座酶、限制性核酸内切酶、乙酰基转移酶、渗透酶、还原酶、氢化酶和脱卤酶的基因,且其中一些涉及插入序列(Insertion sequence) 转座元件。氢化酶基因与有机卤呼吸细菌利用电子供体的能力相关,脱卤单胞菌基因组上编码氢化酶基因簇hypABCDEF、多个[Ni-Fe]氢化酶基因和镍依赖性氢化酶基因。氢化酶负责催化H2转化为H+释放出电子。目前对于脱卤单胞菌由电子供体到电子受体的电子传递过程研究较少,最新的研究表明D. alkenigignens BRE15M菌株的还原性脱卤酶复合物中,两个吸氢型氢化酶亚基(HupL和HupS) 组成电子输入模块HupLS,催化由H2生成H+的反应,电子经铁硫蛋白HupX和具有钼蝶呤结合基序的氧化还原蛋白亚基(OmeA、OmeB) 传递至还原性脱卤酶[32]。

表 1 脱卤单胞菌基因组特征Table 1 Genomic features of Dehalogenimonas

| Strains | Genome size (Mb) | DNA G+C content (mol%) | Protein coding genes | rdhA | rdhB |

| D. lykanthroporepellens BL-DC-9 | 1.69 | 55.0 | 1 720 | 25 | 6 |

| D. alkenigignens IP3-3 | 1.85 | 55.9 | 1 936 | 29 | 3 |

| D. alkenigignens BRE15M | 1.65 | 56.3 | 1 795 | 31 | 8 |

| D. formicexedens NSZ-14 | 2.09 | 54.0 | 2 165 | 25 | 6 |

| Dehalogenimonas sp. WBC-2 | 1.72 | 49.0 | n.d. | 22 | 1 |

| “Dehalogenimonas etheniformans” GP | 2.07 | 51.9 | 2 006 | 50 | 4 |

表选项

除氢气外,已知脱卤单胞菌纯培养菌株能够利用甲酸盐作为电子供体,这是由于其基因组上编码了含硒代半胱氨酸的甲酸脱氢酶(Formate dehydrogenase) 基因。甲酸脱氢酶这一基因最初注释于D. formicexedens NSZ-14菌株的基因组,随后在D. lykanthroporepellens BL-DC-9、. D. alkenigignens IP3-3和“Candidatus Dehalogenimonas etheniformans” GP菌株的基因组中也发现了其同源基因,由这些同源基因预测出的氨基酸序列与NSZ-14菌株具有66.0%–90.7%的相似性[18, 34]。脱卤拟球菌也含有该基因的同源基因,然而,这些同源基因的氨基酸序列与NSZ-14菌株的一致性较低(52%–53%),在关键位置上编码硒代半胱氨酸的密码子被编码丝氨酸的密码子所取代,这一特征可能是脱卤拟球菌菌株无法利用甲酸盐作为电子供体的原因[36]。D. formicexedens NSZ-14、D. alkenigignens IP3-3及D. lykanthroporepellens BL-DC-9等菌株基因组中均存在完整的与硒代半胱氨酸合成和插入相关的操纵子(selCDAB)[18, 20-21, 34]。

已测序的脱卤单胞菌基因组中含有22–52个编码还原性脱卤酶(Reductive dehalogenase) A亚基的同源基因(rdhA)。在所有已知的有机卤呼吸细菌的还原性脱卤酶基因中,完整且具有功能的rdhA基因常与编码具有跨膜螺旋的疏水性膜锚定蛋白(RdhB,约90 aa) 的基因rdhB相邻,两者以rdhAB操纵子的组织形式共转录,其编码的蛋白质(RdhA,约500 aa) 在N端含有双精氨酸转位(Tat) 跨膜信号序列,在C端含有两个铁硫簇结合序列[9, 35, 37-47]。然而与其他有机卤呼吸细菌相比,脱卤单胞菌基因组上的大多数rdhA基因都缺乏同源的膜锚定蛋白基因rdhB (表 2)。以D. lykanthroporepellens BL-DC-9菌株为例,其基因组上共注释出了25个rdhA基因,包括17个完整的rdhA基因和8个缺少双精氨酸序列或基本上被截短的rdhA基因,完整的rdhA中仅有6个与同源的rdhB相邻[21, 48]。目前普遍认为RdhB蛋白起到协助脱卤酶转运到细胞质膜外的作用。但脱卤单胞菌GP表达的一些RdhA被预测拥有一个Sec信号肽和跨膜区域,表明可能并非所有的RdhA蛋白都需要RdhB协助来发挥催化活性[16]。缺乏RdhB的RdhA能否发挥催化活性,或者单个RdhB是否可能协助多个RdhA的跨膜转运,以及RdhA与细胞质膜相互作用的机理还有待进一步研究。

表 2 脱卤单胞菌还原性脱卤酶及其功能Table 2 The reductive dehalogenases characterized in Dehalogenimonas

| Name | Reactionsa | Molecular weight (kDa) | GenBank accession number | References |

| DcpA | 1, 2-DCP→Propene | 53.81 | WP_013218938 | [49] |

| TdrA | tDCE→VC | 64.06 | AKG53095 | [33] |

| CerA | VC→Ethene | 61.96 | QNT77188.1 | [16] |

| a: 1, 2-DCP: 1, 2-dichloropropane; tDCE: trans-1, 2-dichloroethene; VC: vinyl chloride. | ||||

表选项

目前在脱卤单胞菌中仅鉴定出了3种还原性脱卤酶,DcpA以二卤消除反应将1, 2-二氯丙烷脱氯为丙烯[49];TdrA通过氢解反应将反式-1, 2-二氯乙烯脱氯为一氯乙烯[33];CerA通过氢解反应将一氯乙烯脱氯为乙烯[16] (表 2)。最初于D. lykanthroporepellens BL-DC-9菌株基因组上编码DcpA的dcpA基因,也存在于Dehalococcoides mccartyi KS菌株和RC菌株中(序列相似性分别为95%和92%)[50]。在BL-DC-9菌株的基因组上,dcpA (位点标签Dehly_1524) 是仅有的6个完整且与rdhB基因相邻的rdhA基因之一。随后在D. alkenigignens IP3-3、D. formicexedens NSZ-14等脱卤单胞菌的基因组上也注释出了高度同源(序列相似性92%–96%) 的dcpA基因[18, 20]。许多环境样品和富集培养中也都可以检测出与D. lykanthroporepellens BL-DC-9菌株dcpA基因高度同源(序列相似性91%–93%) 的序列,表明dcpA或DcpA是可以指示1, 2-二氯丙烷发生脱氯降解的生物标志物,用于1, 2-二氯丙烷原位生物修复的监测[40, 49, 51-52]。TdrA是在脱卤单胞菌WBC-2菌株中鉴定出的将反式-1, 2-二氯乙烯脱氯为一氯乙烯的还原性脱卤酶,与来自Dehalococcoides mccartyi FL2菌株的可降解多种氯代烯烃的TceA (GenBank登录号:AY165309.1)序列的相似度为74.6%。在此之前所报道的脱卤单胞菌都只能以二卤消除方式对氯代烷烃进行脱氯,这一发现证明了其也可以通过氢解的脱氯方式利用氯代烯烃。但通过分析tdrAB操纵子所处的基因岛性质推断tdrAB操纵子是通过横向基因迁移获得的[33]。CerA是在“Candidatus Dehalogenimonas etheniformans” GP菌株中鉴定出的一氯乙烯还原性脱卤酶,与同样具有一氯乙烯还原功能的TceA、BvcA (GenBank登录号:AAT64888) 及VcrA (GenBank登录号:WP_012882535) 分别具有83.3%、56.1%和49%的蛋白序列相似性[16]。菌株GP可以降解包括剧毒的一氯乙烯在内的多种氯乙烯化合物。综上所述,脱卤单胞菌基因组中的大量未得到生化鉴定的还原性脱卤酶基因资源还有待进一步挖掘。

4 脱卤单胞菌的环境分布及对污染场地修复的应用前景脱卤单胞菌的多样性分布显示出其重要的生态作用[13, 53-56],对从美国和澳大利亚111个有机氯污染场地收集的1 173个地下水样品的分析发现,脱卤单胞菌16S rRNA基因被频繁检出,在65%的样品中其16S rRNA基因拷贝数超过脱卤拟球菌[16, 57]。越来越多的研究表明,脱卤单胞菌是受污染含水层中介导有机氯化物还原脱氯反应的重要种群,其潜力也许远远超过我们目前所知。以往有机氯污染场地修复的研究总是将脱卤拟球菌的16S rRNA基因以及相关脱卤酶基因tceA、vcrA和bvcA作为指导和决策修复的重要生物标志物[58]。但在实际修复中会出现一氯乙烯消失但并未检测到脱卤拟球菌相关标志物出现和增加的情况。除了非生物和好氧氧化作用[59-60],脱卤单胞菌的发现表明,自然界中更广泛多样的有机卤呼吸细菌参与了氯代烷烃、氯代芳香烃以及氯代烯烃,特别是一氯乙烯的厌氧代谢和解毒过程。因而,有必要增加脱卤单胞菌的生物标记基因作为微生物还原脱氯过程驱动污染物去除的依据。已有研究脱卤单胞菌的富集培养与分离大多取样于有机氯污染场地中,而“Candidatus Dehalogenimonas etheniformans” GP菌株的分离表明,未受有机氯化物污染的环境中也存在脱卤单胞菌生物资源。对一些人为干扰少的环境样品的16S rRNA基因测序发现,比较原始的北极湖泊以及贝加尔湖的光层(0–25 m) 和近底区(1 465–1 515 m) 均发现了脱卤单胞菌16S rRNA基因序列[61-62]。进一步证明除了降解人为产生的有机氯污染物,脱卤单胞菌在自然界的卤素循环中也发挥着重要作用[54]。

脱卤单胞菌的另一个重要特征是具有降解高浓度氯代烷烃的能力。D. lykanthroporepellens BL-DC-9、D. alkenigignens IP3-3和D. formicexedens NSZ-14菌株可耐受并脱氯降解浓度分别高达8.7 mmol/L、4.0 mmol/L和3.5 mmol/L的1, 1, 2-三氯乙烷,这对修复受到有机氯严重污染的土壤和地下水有着重要意义[63]。Chen等的应用性研究表明,将可发酵糖浆废液和碳酸氢钠缓冲剂注入地下水,采用定量聚合酶链式反应方法进行检测,脱卤单胞菌16S rRNA基因拷贝数增加超过100倍,同时1, 1, 2-三氯乙烷和1, 2-二氯乙烷浓度显著降低[13]。Schmitt等以乳化植物油(EVO) 和乳酸作为生物刺激性底物,接种脱卤单胞菌实现了对1, 2, 3-三氯丙烷污染场地的生物强化修复[64]。这些研究表明,在修复多氯代烷烃污染地下水的应用中,脱卤单胞菌适用于通过发酵以产生其电子供体H2的生物刺激和生物强化两种通用修复方式。还有研究利用地下水再循环系统,在提高电子供体浓度的同时,降低竞争性电子受体(如硫酸盐) 和特定抑制剂(如氯仿) 的浓度,使脱卤单胞菌16S rRNA基因拷贝数增加2–3个数量级,有效减少其他微生物过程对有机卤呼吸过程的竞争,从而提高修复效率[65]。

有关脱卤单胞菌纯培养和富集培养的研究已经表明它们可以利用不同类型的有机氯化物,在有机氯污染场地的原位修复中具有很大潜力。同时,脱卤单胞菌还能与其他有机卤呼吸细菌联合对难降解有机氯化物进行彻底的脱氯降解。如Qiao等建立的可将1, 2, 4-三氯苯脱氯降解为苯的富集培养体系中,脱卤单胞菌利用1, 2, 4-三氯代苯和1, 2-/1, 3-二氯代苯异构体进行单脱氯,脱卤杆菌Dehalobacter则进一步对生成的1, 4-二氯苯和一氯苯进行脱氯降解,最终将氯离子全部脱除[26]。这些结果启发我们在进行场地修复中,除脱卤拟球菌标志物外,还需要监测包括脱卤单胞菌在内的更广谱的有机卤呼吸细菌标志物,从而更加准确地指导和评价修复进程。

目前脱卤拟球菌菌剂的商业化开发和应用案例已有较多报道[58, 66],而脱卤单胞菌与脱卤拟球菌进化距离最近,并且具有重要的生态功能,其对污染环境有机卤化物降解的贡献还没有得到充分认识。脱卤单胞菌的大量疑似还原性脱卤酶仍未得到生化鉴定,今后的研究需要进一步发掘脱卤单胞菌的还原性脱卤酶基因资源,开发适合脱卤单胞菌的生化、遗传及分子生物学工具以阐明这些还原性脱卤酶的功能及底物范围,增加用于监测污染场地有机氯降解进程的生物标志物。未来对脱卤单胞菌的生理生化性质及基因组信息还需要进行深入的研究,拓展有机氯化物降解微生物的菌种资源,从而发展绿色高效的修复有机氯污染场地的生物技术。

参考文献

| [1] | DeWeerd KA, Mandelco L, Tanner RS, et al. Desulfomonile tiedjei gen. nov. and sp. nov., a novel anaerobic, dehalogenating, sulfate-reducing bacterium. Arch Microbiol, 1990, 154(1): 23-30. |

| [2] | L?ffler FE, Yan J, Ritalahti KM, et al. Dehalococcoides mccartyi gen. nov., sp. nov., obligately organohalide-respiring anaerobic bacteria relevant to halogen cycling and bioremediation, belong to a novel bacterial class, Dehalococcoidia classis nov., order Dehalococcoidales ord. nov. and family Dehalococcoidaceae fam. nov., within the phylum Chloroflexi. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol, 2013, 63(Pt 2): 625-635. |

| [3] | Maymó-Gatell X, Chien Y, Gossett JM, et al. Isolation of a bacterium that reductively dechlorinates tetrachloroethene to ethene. Science, 1997, 276(5318): 1568-1571. DOI:10.1126/science.276.5318.1568 |

| [4] | Utkin I, Woese C, Wiegel J. Isolation and characterization of Desulfitobacterium dehalogenans gen. nov., sp. nov., an anaerobic bacterium which reductively dechlorinates chlorophenolic compounds. Int J Syst Bacteriol, 1994, 44(4): 612-619. DOI:10.1099/00207713-44-4-612 |

| [5] | Holliger C, Hahn D, Harmsen H, et al. Dehalobacter restrictus gen. nov. and sp. nov., a strictly anaerobic bacterium that reductively dechlorinates tetra- and trichloroethene in an anaerobic respiratio. Arch Microbiol, 1998, 169(4): 313-321. DOI:10.1007/s002030050577 |

| [6] | Yan J, Rash BA, Rainey FA, et al. Isolation of novel bacteria within the Chloroflexi capable of reductive dechlorination of 1, 2, 3-trichloropropane. Environ Microbiol, 2009, 11(4): 833-843. DOI:10.1111/j.1462-2920.2008.01804.x |

| [7] | Moe WM, Yan J, Nobre MF, et al. Dehalogenimonas lykanthroporepellens gen. nov., sp. nov., a reductively dehalogenating bacterium isolated from chlorinated solvent-contaminated groundwater. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol, 2009, 59(Pt 11): 2692-2697. |

| [8] | Maphosa F, de Vos WM, Smidt H. Exploiting the ecogenomics toolbox for environmental diagnostics of organohalide-respiring bacteria. Trends Biotechnol, 2010, 28(6): 308-316. DOI:10.1016/j.tibtech.2010.03.005 |

| [9] | Hug LA, Maphosa F, Leys D, et al. Overview of organohalide-respiring bacteria and a proposal for a classification system for reductive dehalogenases. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci, 2013, 368(1616): 20120322. DOI:10.1098/rstb.2012.0322 |

| [10] | Paul L, Herrmann S, Koch CB, et al. Inhibition of microbial trichloroethylene dechlorination by Fe(Ⅲ) reduction depends on Fe mineralogy: a batch study using the bioaugmentation culture KB-1. Water Res, 2013, 47(7): 2543-2554. DOI:10.1016/j.watres.2013.02.029 |

| [11] | Peale JGD, Mueller J, Molin J. Successful ISCR-enhanced bioremediation of a TCE DNAPL source utilizing EHC? and KB-1?. Remediation, 2010, 20(3): 63-81. DOI:10.1002/rem.20251 |

| [12] | Kanitkar YH, Stedtfeld RD, Steffan RJ, et al. Loop-mediated isothermal amplification (LAMP) for rapid detection and quantification of Dehalococcoides biomarker genes in commercial reductive dechlorinating cultures KB-1 and SDC-9. Appl Environ Microbiol, 2016, 82(6): 1799-1806. DOI:10.1128/AEM.03660-15 |

| [13] | Chen J, Bowman KS, Rainey FA, et al. Reassessment of PCR primers targeting 16S rRNA genes of the organohalide-respiring genus Dehalogenimonas. Biodegradation, 2014, 25(5): 747-756. DOI:10.1007/s10532-014-9696-z |

| [14] | 吕燕, 李秀颖, 王晶晶, 等. 一株脱卤单胞菌属有机卤呼吸细菌的分离纯化与基础特征. 微生物学报, 2021, 6(4): 1016-1029. Lü Y, Li XY, Wang JJ, et al. Isolation and basic characterization of a novel organohalide-respiring bacterium within the genus Dehalogenimonas. Acta Microbiol Sin, 2021, 6(4): 1016-1029 (in Chinese). |

| [15] | Manchester MJ, Hug LA, Zarek M, et al. Discovery of a trans-dichloroethene-respiring Dehalogenimonas species in the 1, 1, 2, 2-tetrachloroethane- dechlorinating WBC-2 consortium. Appl Environ Microbiol, 2012, 78(15): 5280-5287. DOI:10.1128/AEM.00384-12 |

| [16] | Yang Y, Higgins SA, Yan J, et al. Grape pomace compost harbors organohalide-respiring Dehalogenimonas species with novel reductive dehalogenase genes. Isme J, 2017, 11(12): 2767-2780. DOI:10.1038/ismej.2017.127 |

| [17] | Bowman KS, Nobre MF, da Costa MS, et al. Dehalogenimonas alkenigignens sp. nov., a chlorinated-alkane-dehalogenating bacterium isolated from groundwater. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol, 2013, 63(Pt 4): 1492-1498. |

| [18] | Key TA, Bowman KS, Lee I, et al. Dehalogenimonas formicexedens sp. nov., a chlorinated alkane-respiring bacterium isolated from contaminated groundwater. Int J Syst Evol Microbio, 2017, 67(5): 1366-1373. DOI:10.1099/ijsem.0.001819 |

| [19] | Dillehay JL, Bowman KS, Yan J, et al. Substrate interactions in dehalogenation of 1, 2-dichloroethane, 1, 2-dichloropropane, and 1, 1, 2-trichloroethane mixtures by Dehalogenimonas spp... Biodegradation, 2014, 25(2): 301-312. DOI:10.1007/s10532-013-9661-2 |

| [20] | Key TA, Richmond DP, Bowman KS, et al. Genome sequence of the organohalide-respiring Dehalogenimonas alkenigignens type strain (IP3-3(T)). Stand Genomic Sci, 2016, 11: 44. DOI:10.1186/s40793-016-0165-7 |

| [21] | Siddaramappa S, Challacombe JF, Delano SF, et al. Complete genome sequence of Dehalogenimonas lykanthroporepellens type strain (BL-DC-9(T)) and comparison to "Dehalococcoides" strains. Stand Genomic Sci, 2012, 6(2): 251-264. DOI:10.4056/sigs.2806097 |

| [22] | Adrian L, L?ffler FE. Organohalide-respiring bacteria — an introduction. Organohalide-Respiring Bacteria. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2016, 3-6. |

| [23] | Wang SQ, He JZ. Phylogenetically distinct bacteria involve extensive dechlorination of aroclor 1260 in sediment-free cultures. PLoS ONE, 2013, 8(3): e59178. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0059178 |

| [24] | Leitner S, Berger H, Gorfer M, et al. Isotopic effects of PCE induced by organohalide-respiring bacteria. Environ Sci Pollut Res, 2017, 24(32): 24803-24815. DOI:10.1007/s11356-017-0075-2 |

| [25] | Murray AM, Ottosen CB, Maillard J, et al. Chlorinated ethene plume evolution after source thermal remediation: determination of degradation rates and mechanisms. J Contam Hydrol, 2019, 227: 103551. DOI:10.1016/j.jconhyd.2019.103551 |

| [26] | Qiao WJ, Luo F, Lomheim L, et al. A Dehalogenimonas population respires 1, 2, 4-trichlorobenzene and dichlorobenzenes. Environ Sci Technol, 2018, 52(22): 13391-13398. DOI:10.1021/acs.est.8b04239 |

| [27] | Felsenstein J. Confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Evolution, 1985, 39(4): 783-791. DOI:10.1111/j.1558-5646.1985.tb00420.x |

| [28] | Kumar S, Stecher G, Li M, et al. MEGA X: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis across computing platforms. Mol Biol Evol, 2018, 35(6): 1547-1549. DOI:10.1093/molbev/msy096 |

| [29] | Saitou N, Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol, 1987, 4(4): 406-425. |

| [30] | Stecher G, Tamura K, Kumar S. Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis (MEGA) for macOS. Mol Biol Evol, 2020, 37(4): 1237-1239. DOI:10.1093/molbev/msz312 |

| [31] | Wu QZ, Watts JEM, Sowers KR, et al. Identification of a bacterium that specifically catalyzes the reductive dechlorination of polychlorinated biphenyls with doubly flanked chlorines. Appl Environ Microbiol, 2002, 68(2): 807-812. DOI:10.1128/AEM.68.2.807-812.2002 |

| [32] | Trueba-Santiso A, Wasmund K, Soder-Walz JM, et al. Genome sequence, proteome profile, and identification of a multiprotein reductive dehalogenase complex in Dehalogenimonas alkenigignens strain BRE15M. J Proteome Res, 2021, 20(1): 613-623. DOI:10.1021/acs.jproteome.0c00569 |

| [33] | Molenda O, Quaile AT, Edwards EA. Dehalogenimonas sp. strain WBC-2 genome and identification of its trans-dichloroethene reductive dehalogenase, TdrA. Appl Environ Microbiol, 2016, 82(1): 40-50. DOI:10.1128/AEM.02017-15 |

| [34] | Yang Y, Yan J, Li X, et al. Genome sequence of "Candidatus Dehalogenimonas etheniformans" strain GP, a vinyl chloride-respiring anaerobe. Microbiol Resour Announc, 2020, 9(50): e01212-20. |

| [35] | Nonaka H, Keresztes G, Shinoda Y, et al. Complete genome sequence of the dehalorespiring bacterium Desulfitobacterium hafniense Y51 and comparison with Dehalococcoides ethenogenes 195. J Bacteriol, 2006, 188(6): 2262-2274. DOI:10.1128/JB.188.6.2262-2274.2006 |

| [36] | Morris RM, Fung JM, Rahm BG, et al. Comparative proteomics of Dehalococcoides spp. reveals strain-specific peptides associated with activity. Appl Environ Microbiol, 2007, 73(1): 320-326. DOI:10.1128/AEM.02129-06 |

| [37] | Nijenhuis I, Zinder SH. Characterization of hydrogenase and reductive dehalogenase activities of Dehalococcoides ethenogenes strain 195. Appl Environ Microbiol, 2005, 71(3): 1664-1667. DOI:10.1128/AEM.71.3.1664-1667.2005 |

| [38] | Fricker AD, LaRoe SL, Shea ME, et al. Dehalococcoides mccartyi strain JNA dechlorinates multiple chlorinated phenols including pentachlorophenol and harbors at least 19 reductive dehalogenase homologous genes. Environ Sci Technol, 2014, 48(24): 14300-14308. DOI:10.1021/es503553f |

| [39] | Fung JM, Morris RM, Adrian L, et al. Expression of reductive dehalogenase genes in Dehalococcoides ethenogenes strain 195 growing on tetrachloroethene, trichloroethene, or 2, 3-dichlorophenol. Appl Environ Microbiol, 2007, 73(14): 4439-4445. DOI:10.1128/AEM.00215-07 |

| [40] | Holmes VF, He J, Lee PKH, et al. Discrimination of multiple Dehalococcoides strains in a trichloroethene enrichment by quantification of their reductive dehalogenase genes. Appl Environ Microbiol, 2006, 72(9): 5877-5883. DOI:10.1128/AEM.00516-06 |

| [41] | Low A, Shen Z, Cheng D, et al. A comparative genomics and reductive dehalogenase gene transcription study of two chloroethene-respiring bacteria, Dehalococcoides mccartyi strains MB and 11a. Sci Rep, 2015, 5: 15204. DOI:10.1038/srep15204 |

| [42] | Mattes TE, Ewald JM, Liang Y, et al. PCB dechlorination hotspots and reductive dehalogenase genes in sediments from a contaminated wastewater lagoon. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int, 2018, 25(17): 16376-16388. DOI:10.1007/s11356-017-9872-x |

| [43] | Molenda O, Puentes Jácome LA, Cao X, et al. Insights into origins and function of the unexplored majority of the reductive dehalogenase gene family as a result of genome assembly and ortholog group classification. Environ Sci Process Impacts, 2020, 22(3): 663-678. DOI:10.1039/C9EM00605B |

| [44] | Parthasarathy A, Stich TA, Lohner ST, et al. Biochemical and EPR-spectroscopic investigation into heterologously expressed vinyl chloride reductive dehalogenase (VcrA) from Dehalococcoides mccartyi strain VS. J Am Chem Soc, 2015, 137(10): 3525-3532. DOI:10.1021/ja511653d |

| [45] | Temme HR, Carlson A, Novak PJ. Presence, diversity, and enrichment of respiratory reductive dehalogenase and non-respiratory hydrolytic and oxidative dehalogenase genes in terrestrial environments. Front Microbiol, 2019, 10: 1258. DOI:10.3389/fmicb.2019.01258 |

| [46] | Tsukagoshi N, Ezaki S, Uenaka T, et al. Isolation and transcriptional analysis of novel tetrachloroethene reductive dehalogenase gene from Desulfitobacterium sp. strain KBC1. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol, 2006, 69(5): 543-553. DOI:10.1007/s00253-005-0022-x |

| [47] | Wagner A, Segler L, Kleinsteuber S, et al. Regulation of reductive dehalogenase gene transcription in Dehalococcoides mccartyi. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci, 2013, 368(1616): 20120317. DOI:10.1098/rstb.2012.0317 |

| [48] | Mukherjee K, Bowman KS, Rainey FA, et al. Dehalogenimonas lykanthroporepellens BL-DC-9(T) simultaneously transcribes many rdhA genes during organohalide respiration with 1, 2-DCA, 1, 2-DCP, and 1, 2, 3-TCP as electron acceptors. FEMS Microbiol Lett, 2014, 354(2): 111-118. DOI:10.1111/1574-6968.12434 |

| [49] | Padilla-Crespo E, Yan J, Swift C, et al. Identification and environmental distribution of dcpA, which encodes the reductive dehalogenase catalyzing the dichloroelimination of 1, 2-dichloropropane to propene in organohalide- respiring Chloroflexi. Appl Environ Microbiol, 2014, 80(3): 808-818. DOI:10.1128/AEM.02927-13 |

| [50] | Higgins SA, Padilla-Crespo E, L?ffler FE. Draft genome sequences of the 1, 2-dichloropropane- respiring Dehalococcoides mccartyi strains RC and KS. Microbiol Resour Announc, 2018, 7(10): e01081-18. |

| [51] | Lee PKH, Johnson DR, Holmes VF, et al. Reductive dehalogenase gene expression as a biomarker for physiological activity of Dehalococcoides spp.. Appl Environ Microbiol, 2006, 72(9): 6161-6168. DOI:10.1128/AEM.01070-06 |

| [52] | Ritalahti KM, Amos BK, Sung Y, et al. Quantitative PCR targeting 16S rRNA and reductive dehalogenase genes simultaneously monitors multiple Dehalococcoides strains. Appl Environ Microbiol, 2006, 72(4): 2765-2774. DOI:10.1128/AEM.72.4.2765-2774.2006 |

| [53] | Yang Y, Sanford R, Yan J, et al. Roles of organohalide-respiring Dehalococcoidia in carbon cycling. mSystems, 2020, 5(3): e00757-19. |

| [54] | 杨毅, 张耀之, 李秀颖, 等. 脱卤球菌纲(Dehalococcoidia Class)在有机卤化物生物地球化学循环中的作用. 环境科学学报, 2019, 39(10): 3207-3214. Yang Y, Zhang YZ, Li XY, et al. Roles of Dehalococcoidia class in the biogeochemical cycle of organohalides. Acta Sci Circumstantiae, 2019, 39(10): 3207-3214 (in Chinese). |

| [55] | Chen J, Wang PF, Wang C, et al. Spatial distribution and diversity of organohalide-respiring bacteria and their relationships with polybrominated diphenyl ether concentration in Taihu Lake sediments. Environ Pollut, 2018, 232: 200-211. DOI:10.1016/j.envpol.2017.08.124 |

| [56] | Dang HY, Kanitkar YH, Stedtfeld RD, et al. Abundance of chlorinated solvent and 1, 4-dioxane degrading microorganisms at five chlorinated solvent contaminated sites determined via shotgun sequencing. Environ Sci Technol, 2018, 52(23): 13914-13924. DOI:10.1021/acs.est.8b04895 |

| [57] | Munro JE, Kimyon ?, Rich DJ, et al. Co-occurrence of genes for aerobic and anaerobic biodegradation of dichloroethane in organochlorine-contaminated groundwater. FEMS Microbiol Ecol, 2017, 93(11): fix133. |

| [58] | Stroo HF, Leeson A, Ward CH. Bioaugmentation for groundwater remediation. New York, NY: Springer New York, 2013. |

| [59] | He YT, Wilson JT, Su C, et al. Review of abiotic degradation of chlorinated solvents by reactive iron minerals in aquifers. Groundwater Monit R, 2015, 35(3): 57-75. DOI:10.1111/gwmr.12111 |

| [60] | Coleman NV, Mattes TE, Gossett JM, et al. Phylogenetic and kinetic diversity of aerobic vinyl chloride-assimilating bacteria from contaminated sites. Appl Environ Microbiol, 2002, 68(12): 6162-6171. DOI:10.1128/AEM.68.12.6162-6171.2002 |

| [61] | Comeau AM, Harding T, Galand PE, et al. Vertical distribution of microbial communities in a perennially stratified Arctic lake with saline, anoxic bottom waters. Sci Rep, 2012, 2: 604. DOI:10.1038/srep00604 |

| [62] | Kurilkina MI, Zakharova YR, Galachyants YP, et al. Bacterial community composition in the water column of the deepest freshwater Lake Baikal as determined by next-generation sequencing. FEMS Microbiol Ecol, 2016, 92(7): fiw094. DOI:10.1093/femsec/fiw094 |

| [63] | Maness AD, Bowman KS, Yan J, et al. Dehalogenimonas spp. can reductively dehalogenate high concentrations of 1, 2-dichloroethane, 1, 2-dichloropropane, and 1, 1, 2-trichloroethane. AMB Express, 2012, 2(1): 54. DOI:10.1186/2191-0855-2-54 |

| [64] | Schmitt M, Varadhan S, Dworatzek S, et al. Optimization and validation of enhanced biological reduction of 1, 2, 3-trichloropropane in groundwater. Remediation, 2017, 28(1): 17-25. DOI:10.1002/rem.21539 |

| [65] | Baldwin BR, Taggart D, Chai YZ, et al. Bioremediation management reduces mass discharge at a chlorinated DNAPL site. Groundwater Monit R, 2017, 37(2): 58-70. DOI:10.1111/gwmr.12211 |

| [66] | L?ffler FE, Edwards EA. Harnessing microbial activities for environmental cleanup. Curr Opin Biotechnol, 2006, 17(3): 274-284. DOI:10.1016/j.copbio.2006.05.001 |