1 西北农林科技大学 动物医学院 神经生物学实验室,陕西 杨凌 712100;

2 西北农林科技大学 食品科学与工程学院,陕西 杨凌 712100;

3 西北农林科技大学 创新实验学院,陕西 杨凌 712100

收稿日期:2017-09-19;接收日期:2017-12-11; 网络出版时间:2017-12-13 基金项目:国家自然科学基金(No. 31572477),陕西省资源主导型产业关键技术项目(No. 2016KTCL02-19)资助

摘要:干细胞研究已成为当今生命科学领域中的前沿和热点问题,该研究为探讨胚胎发生、组织细胞分化以及基因表达调控等生物学问题提供了理想的模型,同时也为临床组织缺陷性疾病和遗传性疾病的细胞治疗和基因治疗开辟了新的手段。其中,经血源性子宫内膜干细胞(Menstrual blood-derived stem cells,MenSCs)来源丰富,具有多向分化潜能和较低的免疫排斥的特性,可以实现个体化治疗,是临床最具有应用优势的干细胞。脑与脊髓作为中枢神经系统,其损伤极为常见,致死率和致残率居各类创伤之首。与周围神经系统损伤相比,中枢神经受损后恢复较为困难,其治疗仍缺乏突破。而MenSCs的治疗有希望解决此难题,故结合近年来国内外对MenSCs的生物学特性及其对中枢神经系统疾病治疗的研究作一综述,从而为中枢神经系统疾病的治疗提供参考。

关键词:经血源性子宫内膜干细胞 分化 中枢神经系统疾病 干细胞治疗 修复

Process in menstrual blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells for treatment of central nervous system diseases

Mengmeng Liu1, Xinran Cheng1, Kaikai Li1, Mingrui Xu2, Yongji Wu1, Mengli Wang1, Qianru Zhang1, Wenyong Yan1, Chang Luo3, Shanting Zhao1

1 Neurobiology Laboratory, College of Veterinary Medicine, Northwest A & F University, Yangling 712100, Shaanxi, China;

2 College of Food Science and Engineering, Northwest A & F University, Yangling 712100, Shaanxi, China;

3 Innovation Experimental College, Northwest A & F University, Yangling 712100, Shaanxi, China

Received: September 19, 2017; Accepted: December 11, 2017; Published: December 13, 2017

Supported by: National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31572477), Resource-based Industry Key Technology Project of Shaanxi Province (No. 2016KTCL02-19)

Corresponding author:Shanting Zhao. Tel/Fax: +86-29-87091032; E-mail: shantingzhao@hotmail.com

Abstract: Stem cell research has become a frontier in the field of life sciences, and provides an ideal model for exploring developmental biology problems such as embryogenesis, histiocytosis, and gene expression regulation, as well as opens up new doors for clinical tissue defective and inheritance diseases. Among them, menstrual blood-derived stem cells (MenSCs) are characterized by wide source, multi-directional differentiation potential, low immune rejection characteristics. Thus, MenSCs can achieve individual treatment and have the most advantage of the clinical application. The central nervous system, including brain and spinal cord, is susceptible to injury. And lethality and morbidity of them tops the list of all types of trauma. Compared to peripheral nervous system, recovery of central nervous system after damage remains extremely hard. However, the treatment of stem cells, especially MenSCs, is expected to solve this problem. Therefore, biological characteristics of MenSCs and their treatment in the respect of central nervous system diseases have been reviewed at home and abroad in recent years, so as to provide reference for the treatment of central nervous system diseases.

Key words: menstrual blood-derived stem cells differentiation central nervous system diseases stem cell treatment repair

与外周神经系统损伤修复相比,中枢神经系统疾病的治疗是公认的世界难题,多项研究表明干细胞治疗有望解决此题。经血源性子宫内膜干细胞(Menstrual blood-derived stem cells,MenSCs)是新近发现的干细胞,既具有来源广、取材易、多向分化潜能等特性,又具有无伦理学问题、可实现个性化治疗及免疫原性低等临床优势。因此,结合本实验室之前对于中枢神经系统疾病原理的探究以及对MenSCs研究的初步结果,本文主要就MenSCs的特性及其在中风、脊髓损伤修复、恶性胶质瘤和多发性硬化等中枢神经系统疾病治疗中的应用作一综述,并展望了MenSCs的应用前景。

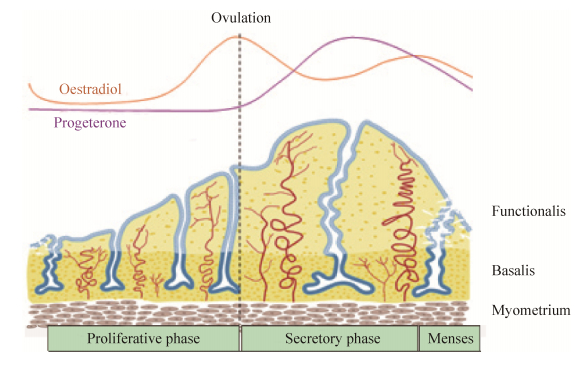

1 经血源性子宫内膜干细胞1.1 经血源性子宫内膜干细胞的发现及来源因血管生成是月经周期中子宫内膜增生的关键环节,Meng等[1]提出能在月经血中分离出干细胞这一假说且得到证实,并将此干细胞命名为子宫内膜再生细胞。之后,Patel等[2]提取、分离、命名该细胞为经血源性子宫内膜基质干细胞,并证明该细胞能分化为中、外两个胚层细胞系。经研究发现MenSCs的确切来源是月经期间子宫内膜功能层脱落而来的月经血,而不是源于骨髓间充质干细胞[3]。子宫壁由内向外分为3层,即子宫内膜、肌层和浆膜,而子宫内膜又分为基底层和功能层。月经周期分为3个时期:增殖期、分泌期和月经期。在月经期间,子宫内膜只有功能层脱落。月经周期受到性类固醇激素等的调控[4] (图 1),在雌激素等调控的增殖期,子宫内膜在10 d内增厚5?7 mm[5];在黄体酮等调控的分泌期,腺体和基质成熟[6];在分泌晚期,黄体退化,引起雌激素和黄体酮的分泌降低,触发子宫内膜功能层脱落[7]。因而,女性月经期间子宫内膜功能层脱落的月经血可以提取并分离出MenSCs。

|

| 图 1 在月经周期中人子宫内膜功能层的变化[4] Figure 1 Schematic of changes in the human endometrium during the menstrual cycle, illustrating the growth, differentiation and shedding of the functionalis layer[4]. |

| 图选项 |

1.2 MenSCs的分离、提取及鉴定方法一是通过密度梯度离心分离出单个核细胞并成功诱导其分化为心肌细胞、呼吸上皮细胞、神经细胞、肌细胞、内皮细胞、胰腺细胞、脂肪细胞和成骨细胞;经流式细胞仪分析该细胞标志物并得到其表型特征为Oct-4、CD105、CD44、CD73和CD9等阳性,而Nanog、SSEA-4、CD45、CD34和CD14等阴性[1]。这是首次证明从月经血中可以分离出干细胞且该细胞具有分化为内、中、外3个胚层细胞系的潜能。方法二是直接离心取沉淀培养,用与子宫内膜高增殖性密切相关的CD117 (c-kit)微磁珠技术筛选细胞,获得的细胞经分析阳性表达SSEA-4以及Oct-4,且可诱导分化为软骨细胞、脂肪细胞、成骨细胞、心肌细胞和神经细胞,证明该细胞能分化为中、外两个胚层细胞系[2]。

不同的收集和处理方法得到的MenSCs可能会在月经血中提取出具有不同生物学特性的细胞群[1-2, 8]。不同的研究者在MenSCs是否表达表面标志物SSEA-4方面的结果仍有争议[1-2]。而研究表明MenSCs表达端粒酶催化亚基和Nanog[9],这对于体外具有高增殖活性的干细胞来说是常见的。此外,MenSCs不表达HLA-DR分子和低表达HLAⅠ类分子[10],这些都进一步为MenSCs的临床应用奠定了基础。

1.3 MenSCs的体外分化最初,Meng等[1]用含GlutaMax和hFGA-4的神经诱导培养基诱导MenSCs分化为表达星形胶质细胞标记物GFAP和神经干细胞标记物Nestin的神经样细胞(Neural like cells,NLCs)。紧接着Patel等[2]在诱导培养基中添加了N2、bFGF以及EGF等诱导MenSCs分化为少突胶质样细胞、神经元样细胞以及神经祖细胞样细胞。后来,Zemel’ko等[9]证明相比于骨髓间充质干细胞和脂肪干细胞,全反式维甲酸对MenSCs的神经分化是必需的。这些方法都为后来的研究奠定了重要基础。总而言之,MenSCs在体外诱导分化为NLCs与神经营养因子或其类似物紧密相连,在诱导条件下,一般先转变为神经祖细胞样细胞,再最终分化为其他NLCs。大量MenSCs体外分化机制的探究为许多不治之症带来了希望。

2 MenSCs与中枢神经系统疾病的治疗脑部疾病是引起人类死亡的第三大原因,而干细胞可以适时地调节炎症,消除细胞死亡,保留神经功能。之前的许多研究中,已经成功地将MenSCs分化成各种细胞系,包括胶质样细胞[11]。与骨髓间充质干细胞相比(表 1),MenSCs具有长期的自我更新能力和较强的增殖能力,较小的核型异常风险,不会引发免疫原性反应或肿瘤形成[12-13]。因此,MenSCs更有可能成为治疗中枢神经系统疾病的“潜力股”。另外,MenSCs取自“废物”——月经血,避免了胚胎干细胞的伦理问题以及骨髓干细胞取材的侵入性,这些特性使得MenSCs的临床应用会变得更加广泛。因此,我们对MenSCs在中枢神经系统疾病如中风[19, 24-25]、脊髓损伤[26]、恶性胶质瘤[27]和多发性硬化[28]等疾病治疗中的应用(表 2)作一阐述。

表 1 经血源性子宫内膜干细胞与骨髓间充质干细胞的比较Table 1 Comparison of menstrual blood-derived endometrial stem cells (MenSCs) with bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BM-MSCs)

| MenSCs | BM-MSCs | |

| Source | Menstrual blood | Bone marrow |

| Surface marker* | CD9+, CD13+, CD29+, CD117+, SSEA4+, CD73+, CD90+, CD105+, HLA I+, HLA-DR-, STRO-1-[1-2, 14-15] | CD9-, CD13-, CD29-, CD117-, SSEA4+, CD73+, CD90+, CD105+, HLA I+, HLA-DR-, STRO-1+[9, 16-18] |

| Immunoreactivity | MenSCs < BM-MSCs[19] | |

| Differentiation | Mesoderm (myocytes, cardiomyocytes, osteocytes, adipocytes), ectoderm (neurons, glial-like cells) or endoderm (hepatocytes, pancreatic cells, respiratory epithelium) origin[1-2, 9, 11, 13] | Numerous cell types of mesenchymal origin, glial cells, neurons, hepatocytes, and pancreatic islet cells[20-21] |

| Self-renewal and proliferation capacity | MenSCs > BM-MSCs[13] | |

| Clinical application | Have stable genome and are not tumorigenic[13, 22] | Exhibit crippling abnormalities, such as reduced proliferation rate, differentiation capacity and passage-associated abnormalities[16, 23] |

| *Cell surface markers are not exactly the same as the table. | ||

表选项

表 2 经血源性子宫内膜干细胞在中枢神经系统疾病治疗中的应用Table 2 Application of menstrual blood-derived endometrial stem cells in the treatment of central nervous system diseases

| Treated diseases/model | Total injected cell concentration | Outcomes | Administration route |

| MCAO stroke animals | 400 thousand or 4 million for intracerebral and intravenous injection, respectively | Robust effects, less neurologic deficit | Intracerebral and intravenous injection |

| Dorsally hemisected SCI rat | 1 million | Neuronal regeneration, axonal remyelination and motor function recovery | Implantation |

| Experimental animal tumor model | 3 million | Migratory capacity, therapeutic efficacy | Tail vein injection |

| Multiple sclerosis | 30 milion | No notable events or abnormities | Intrathecal infusion |

| Abbreviation: MCAO middle cerebral artery occlusion. | |||

表选项

2.1 MenSCs与中风“脑卒中”又称“中风”、“脑血管意外”,是一种急性脑血管疾病,具有发病率高、死亡率高和致残率高的特点,也是导致中国成年人残疾的首要原因,然而一直缺乏有效的治疗手段,干细胞治疗有望解决此难题。

众所周知,中风不仅仅影响神经元的功能,而且涉及到与其周围免疫系统相互作用的“血管神经纤维瘤”中的脑细胞及其细胞外基质。由于这些原因,中风的治疗应针对这些系统,而不是只针对个别的损伤过程,才能避免过去临床转化开发特定神经保护药物的失败尝试。Borlongan等[29]使用Patel等[2]描述的MenSCs研究中风的体外和体内模型的治疗。研究发现这些细胞提供了一些保护原代神经元免受氧-葡萄糖剥夺的物质。进一步研究发现这些物质能够发挥类似的神经保护作用,这可能与血管内皮生长因子、脑源性生长因子和神经营养因子3有关。早先,关于其他干细胞系的研究也发现了一种或多种因子的释放[30-31]及其对卒中治疗的潜在益处[32],该研究明确表示无论是在脑内还是在静脉内自体移植MenSCs均未显示免疫抑制;实验诱导成年大鼠缺血性卒中后,其行为学和组织学损伤显著降低。因此,移植MenSCs而得的神经结构和血管生成能力可以成为中风治疗的有效途径,也支持它们成为用于其他基底神经节疾病,如帕金森病和亨廷顿病治疗的干细胞来源。

2.2 MenSCs与脊髓损伤修复脊髓损伤(Spinal cord injury,SCI)是一种创伤性损伤,可导致运动神经元或感觉神经元的损失。与周围神经系统相比,脊髓的有限再生能力是源于创伤后环境,如缺血、炎症、免疫应答和胶质瘢痕的形成[33]。已经证明,干细胞治疗可通过释放一系列内源性修复的营养因子或通过分化成神经元或神经胶质细胞以替换受损细胞来促进SCI后的神经元再生[34-36]。另外,三维支架通过模拟内源性微环境更有利地支持细胞存活、增殖和体内分化。故将工程支架与干细胞结合可能成为治疗SCI的有前途的策略。

MenSCs作为具有多种临床应用优势的干细胞,已有研究将其种植在一种纳米纤维上,再植入到背侧半透明的大鼠模型中,可以减轻二次反应,促进神经元再生、轴突髓鞘再生和运动功能恢复[26]。此外,作为抗炎和神经保护介质的番茄红素的同时,给药可以抑制神经变性过程并帮助改善神经元再生。这表明MenSCs的移植并结合支架可以更好地促进损伤部位细胞的恢复,成为有效治疗SCI的方法。

2.3 MenSCs与胶质瘤神经胶质瘤是中枢神经系统中最常见和最恶性的脑肿瘤。肿瘤细胞的侵袭性和浸润性以及有效治疗的困难导致预后很差。尽管手术、放疗、化疗甚至基因治疗已被广泛应用,但胶质瘤的5年生存率仍低于10%[37]。因此,迫切需要一种消除侵袭性肿瘤细胞而不损伤正常脑组织的新的治疗手段。

研究表明,肿瘤坏死因子相关凋亡诱导配体(Tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand,TRAIL)可以通过激活凋亡途径诱导癌细胞凋亡。结构分析表明,分泌型TRAIL (sTRAIL)含有蛋白质的受体结合域,可用于选择性触发癌细胞凋亡而不损害正常细胞[38]。而Wang等[27]结合sTRAIL与MenSCs靶向治疗恶性胶质瘤,为神经胶质瘤的治疗带来了新的思路。在该研究中,当用作治疗药物的基因递送载体时,MenSCs显示人类恶性胶质瘤的向性。而感染过表达sTRAIL的有效腺病毒血清型35载体的MenSCs在体外和体内均显示出显著的抗肿瘤作用。在此,MenSCs既具有干细胞增殖、分化的优点,又作为sTRAIL等药物靶向治疗的载体,正是治疗胶质瘤的希望所在。

2.4 MenSCs与多发性硬化多发性硬化症(Multiple sclerosis, MS)是一种常见的中枢神经脱髓鞘疾病,伴随着胶质纤维增生而形成钙化斑,多见于视神经、脊髓和脑干。

目前,虽然已有多种疾病缓解疗法(Disease-modifying therapies,DMTs)获得批准治疗MS[39],但仍没有有效药物能阻止该疾病进展或直接促进已有中枢神经系统损伤的修复。使用干细胞治疗不仅可以减弱免疫反应,还能更好地促进内源性修复机制的运行。Zhong等[28]认为MenSCs是具有多能分化活性和诱导新血管发生能力的间充质干细胞群,在体外和动物体内的研究都表明MenSCs具有免疫特性,在某些情况下能主动抑制免疫应答,并报道了1例静脉内和鞘内注射MenSCs以及3例鞘内注射MenSCs临床治疗多发性硬化症患者的初步安全性研究。经最长超过一年的随访,病人并没有出现免疫反应或治疗相关的不良反应。这些初步数据表明MenSCs在临床治疗的可行性,并支持使用这种新型干细胞治疗疾病的进一步研究。

Naddafi等[40]研究表明尼古丁在多发性硬化症实验模型中具有保护作用。而后,Mahfouz等[41]揭示间充质干细胞和尼古丁的组合可以进一步改善MS,可成为MS治疗的有希望的策略。所以,以细胞为基础的治疗(移植、动员和药物治疗)可能有助于退行性机制导致的多发性硬化症的治疗,但这一假设有待进一步证实[42]。因此,MenSCs这种无入侵性、来源广、免疫原性较低的干细胞结合药物一起治疗MS或许是一种不错的选择。

3 展望移植的干细胞可以提供新的神经元以及分泌细胞因子以形成新的功能性神经回路并促进轴突再生[43-45]。基于干细胞的治疗方法可以促进神经元再建、抑制细胞凋亡、轴突再生和髓鞘形成。最新研究报道,神经干细胞和间充质干细胞已经用于损伤脊髓的细胞替代疗法。然而,神经干细胞治疗脊髓损伤的结果并不理想,很大程度上是由于神经胶质瘢痕组成以及神经干细胞体内分化的复杂性而导致的突触靶向再生的阻碍[46-48]。此外,神经干细胞治疗还存在以下问题:1)移植后的神经干细胞存活时间短[49];2)所移植的神经干细胞纯度及其可能与其他宿主神经细胞之间产生的不可预测的相互作用[49-50];3)移植后的神经干细胞可能逃脱分化和选择过程并在移植部位扩大形成肿瘤[50-51]。而间充质干细胞表现出的下调促凋亡因子、上调抗细胞凋亡分子以及阻碍轴突脱髓鞘和退化的能力,已被提倡作为干细胞治疗的“明日之星”[52]。但是,宿主免疫应答、神经分化的缺乏和移植细胞的低存活率仍是使用间充质干细胞的限制[53]。

此时,“应召而来”的MenSCs是适用于细胞治疗的新型的干细胞来源[54-55]。这些细胞不仅具有分离、提取的非侵入性和快速扩增特性,还表现出高增殖潜力,有分化成为具神经源性细胞类型的能力[2, 56]。研究表明,MenSCs免疫原性较低,已经在治疗子宫内膜异位症[57]、卵巢早衰症[58]、Asherman综合症[59]等子宫疾病、高血糖症[60]、胶原诱导的关节炎和异物移植物抗宿主病[10]、急性肝功能衰竭[61]、皮肤创伤[62]以及急性肺损伤[63]等疾病的研究中得以证实。

值得一提的是,间充质干细胞的免疫调节机制并不总是相同,而是取决于众多相关因素的相互作用,需要更进一步的研究来阐述其在不同疾病状态下的特异效应[64],这对于MenSCs来说也不例外。此外,干细胞包括MenSCs的治疗仍面临着很多问题,如移植后细胞的存活、细胞命运、维持指定的细胞分化表型、避免畸胎瘤的形成及移植的安全性等问题。为解决这些问题,将组织工程与干细胞技术结合应用可能是一个非常不错的选择,如上述胶质瘤和脊髓损伤的治疗。因此MenSCs在临床应用之前不仅需要有充足的研究积淀,还需要进行全面可靠的安全评估。

参考文献

| [1] | Meng XL, Ichim TE, Zhong J, et al. Endometrial regenerative cells: a novel stem cell population.J Transl Med, 2007, 5: 57.DOI: 10.1186/1479-5876-5-57 |

| [2] | Patel AN, Park E, Kuzman M, et al. Multipotent menstrual blood stromal stem cells: isolation, characterization, and differentiation.Cell Transplant, 2008, 17(3): 303–311.DOI: 10.3727/096368908784153922 |

| [3] | Azedi F, Kazemnejad S, Zarnani AH, et al. Comparative capability of menstrual blood versus bone marrow derived stem cells in neural differentiation.Mol Biol Rep, 2017, 44(1): 169–182.DOI: 10.1007/s11033-016-4095-7 |

| [4] | Emmerson SJ, Gargett CE. Endometrial mesenchymal stem cells as a cell based therapy for pelvic organ prolapse.World J Stem Cells, 2016, 8(5): 202–215.DOI: 10.4252/wjsc.v8.i5.202 |

| [5] | McLennan CE, Rydell AH. Extent of endometrial shedding during normal menstruation.Obstet Gynecol, 1965, 26(5): 605–621. |

| [6] | Gargett CE, Chan RW, Schwab KE. Hormone and growth factor signaling in endometrial renewal: role of stem/progenitor cells.Mol Cell Endocrinol, 2008, 288(12): 22–29. |

| [7] | Padykula HA, Coles LG, McCracken JA, et al. A zonal pattern of cell proliferation and differentiation in the rhesus endometrium during the estrogen surge.Biol Reprod, 1984, 31(5): 1103–1118.DOI: 10.1095/biolreprod31.5.1103 |

| [8] | Hida N, Nishiyama N, Miyoshi S, et al. Novel cardiac precursor-like cells from human menstrual blood-derived mesenchymal cells.Stem Cells, 2008, 26(7): 1695–1704.DOI: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-0826 |

| [9] | Zemel'ko VI, Kozhukharova IB, Alekseenko LL, et al. Neurogenic potential of human mesenchymal stem cells isolated from bone marrow, adipose tissue and endometrium: a comparative study.Tsitologiia, 2013, 55(2): 101–110. |

| [10] | Luz-Crawford P, Torres MJ, No?l D, et al. The immunosuppressive signature of menstrual blood mesenchymal stem cells entails opposite effects on experimental arthritis and graft versus host diseases.Stem Cells, 2016, 34(2): 456–469.DOI: 10.1002/stem.2244 |

| [11] | Azedi F, Kazemnejad S, Zarnani AH, et al. Differentiation potential of menstrual blood-versus bone marrow-stem cells into glial-like cells.Cell Biol Int, 2014, 38(5): 615–624.DOI: 10.1002/cbin.v38.5 |

| [12] | Darzi S, Zarnani AH, Jeddi-Tehrani M, et al. Osteogenic differentiation of stem cells derived from menstrual blood versus bone marrow in the presence of human platelet releasate.Tissue Eng Part A, 2012, 18(15/16): 1720–1728. |

| [13] | Khanjani S, Khanmohammadi M, Zarnani AH, et al. Comparative evaluation of differentiation potential of menstrual blood-versus bone marrow-derived stem cells into hepatocyte-like cells.PLoS ONE, 2014, 9(2): e86075.DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0086075 |

| [14] | Lai DM, Guo Y, Zhang QW, et al. Differentiation of human menstrual blood-derived endometrial mesenchymal stem cells into oocyte-like cells.Acta Biochim Biophys Sin, 2016, 48(11): 998–1005.DOI: 10.1093/abbs/gmw090 |

| [15] | Farzamfar S, Naseri-Nosar M, Ghanavatinejad A, et al. Sciatic nerve regeneration by transplantation of menstrual blood-derived stem cells.Mol Biol Rep, 2017, 44(5): 407–412.DOI: 10.1007/s11033-017-4124-1 |

| [16] | Stolzing A, Jones E, McGonagle D, et al. Age-related changes in human bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells: consequences for cell therapies.Mech Ageing Dev, 2008, 129(3): 163–173.DOI: 10.1016/j.mad.2007.12.002 |

| [17] | Cao XK, Li R, Sun W, et al. Co-combination of islets with bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells promotes angiogenesis.Biomed Pharmacother, 2016, 78: 156–164.DOI: 10.1016/j.biopha.2016.01.007 |

| [18] | Hayward JA, Ellis CE, Seeberger K, et al. Cotransplantation of mesenchymal stem cells with neonatal porcine islets improve graft function in diabetic mice.Diabetes, 2017, 66(5): 1312–1321.DOI: 10.2337/db16-1068 |

| [19] | Allickson JG, Sanchez A, Yefimenko N, et al. Recent studies assessing the proliferative capability of a novel adult stem cell identified in menstrual blood.Open Stem Cell J, 2011, 3(2011): 4–10. |

| [20] | Woodbury D, Schwarz EJ, Prockop DJ, et al. Adult rat and human bone marrow stromal cells differentiate into neurons.J Neurosci Res, 2000, 61(4): 364–370.DOI: 10.1002/(ISSN)1097-4547 |

| [21] | Sato Y, Araki H, Kato J, et al. Human mesenchymal stem cells xenografted directly to rat liver are differentiated into human hepatocytes without fusion.Blood, 2005, 106(2): 756–763.DOI: 10.1182/blood-2005-02-0572 |

| [22] | Murphy MP, Wang H, Patel AN, et al. Allogeneic endometrial regenerative cells: an "off the shelf solution" for critical limb ischemia?.J Transl Med, 2008, 6: 45.DOI: 10.1186/1479-5876-6-45 |

| [23] | Roobrouck VD, Ulloa-Montoya F, Verfaillie CM. Self-renewal and differentiation capacity of young and aged stem cells.Exp Cell Res, 2008, 314(9): 1937–1944.DOI: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2008.03.006 |

| [24] | Rodrigues MCO, Glover LE, Weinbren N, et al. Toward personalized cell therapies: autologous menstrual blood cells for stroke.J Biomed Biotechnol, 2011, 2011: 194720. |

| [25] | Rodrigues MC, Voltarelli J, Sanberg PR, et al. Recent progress in cell therapy for basal ganglia disorders with emphasis on menstrual blood transplantation in stroke.Neurosci Biobehav Rev, 2012, 36(1): 177–190.DOI: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2011.05.010 |

| [26] | Terraf P, Kouhsari SM, Ai J, et al. Tissue-engineered regeneration of hemisected spinal cord using human endometrial stem cells, poly ε-caprolactone scaffolds, and crocin as a neuroprotective agent.Mol Neurobiol, 2017, 54(7): 5657–5667.DOI: 10.1007/s12035-016-0089-7 |

| [27] | Wang XJ, Xiang BY, Ding YH, et al. Human menstrual blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells as a cellular vehicle for malignant glioma gene therapy.Oncotarget, 2017, 8(35): 58309–58321. |

| [28] | Zhong ZH, Patel AN, Ichim TE, et al. Feasibility investigation of allogeneic endometrial regenerative cells.J Transl Med, 2009, 7: 15.DOI: 10.1186/1479-5876-7-15 |

| [29] | Borlongan CV, Kaneko Y, Maki M, et al. Menstrual blood cells display stem cell-like phenotypic markers and exert neuroprotection following transplantation in experimental stroke.Stem Cells Dev, 2010, 19(4): 439–452.DOI: 10.1089/scd.2009.0340 |

| [30] | Kurozumi K, Nakamura K, Tamiya T, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells that produce neurotrophic factors reduce ischemic damage in the rat middle cerebral artery occlusion model.Mol Ther, 2005, 11(1): 96–104.DOI: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2004.09.020 |

| [31] | Yasuhara T, Hara K, Maki M, et al. Mannitol facilitates neurotrophic factor up-regulation and behavioural recovery in neonatal hypoxic-ischaemic rats with human umbilical cord blood grafts.J Cell Mol Med, 2010, 14(4): 914–921.DOI: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2008.00671.x |

| [32] | Sun YJ, Jin KL, Xie L, et al. VEGF-induced neuroprotection, neurogenesis, and angiogenesis after focal cerebral ischemia.J Clin Invest, 2003, 111(12): 1843–1851.DOI: 10.1172/JCI200317977 |

| [33] | Snyder EY, Teng YD. Stem cells and spinal cord repair.New Engl J Med, 2012, 366(20): 1940–1942.DOI: 10.1056/NEJMcibr1200138 |

| [34] | Morita T, Sasaki M, Kataoka-Sasaki Y, et al. Intravenous infusion of mesenchymal stem cells promotes functional recovery in a model of chronic spinal cord injury.Neuroscience, 2016, 335: 221–231.DOI: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2016.08.037 |

| [35] | Satti HS, Waheed A, Ahmed P, et al. Autologous mesenchymal stromal cell transplantation for spinal cord injury: a phase Ⅰ pilot study.Cytotherapy, 2016, 18(4): 518–522.DOI: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2016.01.004 |

| [36] | Zhou HL, Zhang XJ, Zhang MY, et al. Transplantation of human amniotic mesenchymal stem cells promotes functional recovery in a rat model of traumatic spinal cord injury.Neurochem Res, 2016, 41(10): 2708–2718.DOI: 10.1007/s11064-016-1987-9 |

| [37] | Nabors LB, Portnow J, Ammirati M, et al. Central nervous system cancers, version 2.2014. Featured updates to the NCCN guidelines.J Natl Compr Canc Netw, 2014, 12(11): 1517–1523.DOI: 10.6004/jnccn.2014.0151 |

| [38] | Walczak H, Miller RE, Ariail K, et al. Tumoricidal activity of tumor necrosis factor-related apoptosis-inducing ligand in vivo.Nat Med, 1999, 5(2): 157–163.DOI: 10.1038/5517 |

| [39] | Ingwersen J, Aktas O, Hartung HP. Advances in and algorithms for the treatment of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis.Neurotherapeutics, 2016, 13(1): 47–57.DOI: 10.1007/s13311-015-0412-4 |

| [40] | Naddafi F, Reza Haidari M, Azizi G, et al. Novel therapeutic approach by nicotine in experimental model of multiple sclerosis.Innov Clin Neurosci, 2013, 10(4): 20–25. |

| [41] | Mahfouz MM, Abdelsalam RM, Masoud MA, et al. The neuroprotective effect of mesenchymal stem cells on an experimentally induced model for multiple sclerosis in mice.J Biochem Mol Toxicol, 2017, 31(9): e21936. |

| [42] | Scolding NJ, Pasquini M, Reingold SC, et al. Cell-based therapeutic strategies for multiple sclerosis.Brain, 2017, 140(11): 2776–2796.DOI: 10.1093/brain/awx154 |

| [43] | Salgado AJ, Oliveira JM, Martins A, et al. Tissue engineering and regenerative medicine: past, present, and future.Int Rev Neurobiol, 2013, 108: 1–33.DOI: 10.1016/B978-0-12-410499-0.00001-0 |

| [44] | Lai BQ, Wang JM, Ling EA, et al. Graft of a Tissue-engineered neural scaffold serves as a promising strategy to restore myelination after rat spinal cord transection.Stem Cells Dev, 2014, 23(8): 910–921.DOI: 10.1089/scd.2013.0426 |

| [45] | Liu C, Huang Y, Pang M, et al. Tissue-engineered regeneration of completely transected spinal cord using induced neural stem cells and gelatin-electrospun poly (lactide-co-glycolide)/polyethylene glycol scaffolds.PLoS ONE, 2015, 10(3): e0117709.DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0117709 |

| [46] | Vroemen M, Aigner L, Winkler J, et al. Adult neural progenitor cell grafts survive after acute spinal cord injury and integrate along axonal pathways.Eur J Neurosci, 2003, 18(4): 743–751.DOI: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02804.x |

| [47] | Webber DJ, Bradbury EJ, McMahon SB, et al. Transplanted neural progenitor cells survive and differentiate but achieve limited functional recovery in the lesioned adult rat spinal cord.Regen Med, 2007, 2(6): 929–945.DOI: 10.2217/17460751.2.6.929 |

| [48] | Shrestha B, Coykendall K, Li YC, et al. Repair of injured spinal cord using biomaterial scaffolds and stem cells.Stem Cell Res Ther, 2014, 5(4): 91.DOI: 10.1186/scrt480 |

| [49] | Keene CD, Chang RC, Leverenz JB, et al. A patient with Huntington's disease and long-surviving fetal neural transplants that developed mass lesions.Acta Neuropathol, 2009, 117(3): 329–338.DOI: 10.1007/s00401-008-0465-0 |

| [50] | Kim SU, Lee HJ, Kim YB. Neural stem cell-based treatment for neurodegenerative diseases.Neuropathology, 2013, 33(5): 491–504. |

| [51] | Wislet-Gendebien S, Poulet C, Neirinckx V, et al. In vivo tumorigenesis was observed after injection of in vitro expanded neural crest stem cells isolated from adult bone marrow.PLoS ONE, 2012, 7(10): e46425.DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046425 |

| [52] | Liang WB, Han QQ, Jin W, et al. The promotion of neurological recovery in the rat spinal cord crushed injury model by collagen-binding BDNF.Biomaterials, 2010, 31(33): 8634–8641.DOI: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.07.084 |

| [53] | Li J, Lepski G. Cell transplantation for spinal cord injury: a systematic review.Biomed Res Int, 2013, 2013: 786475. |

| [54] | Dimitrov R, Timeva T, Kyurkchlev D, et al. Characterization of clonogenic stromal cells isolated from human endometrium.Reproduction, 2008, 135(4): 551–558.DOI: 10.1530/REP-07-0428 |

| [55] | Mobarakeh ZT, Ai J, Yazdani F, et al. Human endometrial stem cells as a new source for programming to neural cells.Cell Biol Int Rep, 2012, 19(1): e00015. |

| [56] | Wolff EF, Gao XB, Yao KV, et al. Endometrial stem cell transplantation restores dopamine production in a Parkinson's disease model.J Cell Mol Med, 2011, 15(4): 747–755.DOI: 10.1111/jcmm.2011.15.issue-4 |

| [57] | Shimizu K, Kamada Y, Sakamoto A, et al. High expression of high-mobility group Box 1 in menstrual blood: implications for endometriosis.Reprod Sci, 2017, 24(11): 1532–1537.DOI: 10.1177/1933719117692042 |

| [58] | Liu T, Huang YY, Zhang J, et al. Transplantation of human menstrual blood stem cells to treat premature ovarian failure in mouse model.Stem Cells Dev, 2014, 23(13): 1548–1557.DOI: 10.1089/scd.2013.0371 |

| [59] | Tan JC, Li PP, Wang QS, et al. Autologous menstrual blood-derived stromal cells transplantation for severe Asherman's syndrome.Hum Reprod, 2016, 31(12): 2723–2729.DOI: 10.1093/humrep/dew235 |

| [60] | Wu XX, Luo YQ, Chen JY, et al. Transplantation of human menstrual blood progenitor cells improves hyperglycemia by promoting endogenous progenitor differentiation in type 1 diabetic mice.Stem Cells Dev, 2014, 23(11): 1245–1257.DOI: 10.1089/scd.2013.0390 |

| [61] | Fathi-Kazerooni M, Tavoosidana G, Taghizadeh-Jahed M, et al. Comparative restoration of acute liver failure by menstrual blood stem cells compared with bone marrow stem cells in mice model.Cytotherapy, 2017, 19(12): 1474–1490.DOI: 10.1016/j.jcyt.2017.08.022 |

| [62] | Akhavan-Tavakoli M, Fard M, Khanjani S, et al. In vitro differentiation of menstrual blood stem cells into keratinocytes: a potential approach for management of wound healing.Biologicals, 2017, 48: 66–73.DOI: 10.1016/j.biologicals.2017.05.005 |

| [63] | Xiang BY, Chen L, Wang XJ, et al. Transplantation of menstrual blood-derived mesenchymal stem cells promotes the repair of LPS-induced acute lung injury.Int J Mol Sci, 2017, 18(4): 689.DOI: 10.3390/ijms18040689 |

| [64] | Waterman RS, Tomchuck SL, Henkle SL, et al. A new mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) paradigm: polarization into a pro-inflammatory MSC1 or an immunosuppressive MSC2 phenotype.PLoS ONE, 2010, 5(4): e10088.DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010088 |