吴志豪1,2, 曾志将1,2, 黄强1,2

1. 江西农业大学蜜蜂研究所, 江西 南昌 330045;

2. 江西省蜜蜂生物学与饲养重点实验室, 江西 南昌 330045

收稿日期:2020-12-11;修回日期:2021-02-20;网络出版日期:2021-06-11

基金项目:国家自然科学基金(32060778);江西农业大学科研启动经费(050014/923230722)

*通信作者:黄强, Tel/Fax: +86-791-83828176;E-mail: qiang-huang@live.com.

摘要:东方蜜蜂微孢子虫病是一种由东方蜜蜂微孢子虫(Nosema ceranae)引起的蜜蜂传染病,已经蔓延到全球。蜜蜂感染东方蜜蜂微孢子虫后会导致早衰、哺育能力下降、生产力和繁殖能力降低,严重时可直接导致蜂群瓦解。本文从传染病学角度出发,对近10年东方蜜蜂微孢子虫病原学、流行病学和防治方法等方面进行总结,以此提高对微孢子虫的认识,为微孢子虫防治提供新思路。

关键词:东方蜜蜂微孢子虫传染病学分析防治方法蜜蜂

The epidemiological analysis of Nosema ceranae

Zhihao Wu1,2, Zhijiang Zeng1,2, Qiang Huang1,2

1. Honeybee Research Institute, Jiangxi Agricultural University, Nanchang 330045, Jiangxi Province, China;

2. Jiangxi Province Key Laboratory of Honeybee Biology and Beekeeping, Nanchang 330045, Jiangxi Province, China

Received: 11 December 2020; Revised: 20 February 2021; Published online: 11 June 2021

*Corresponding author: Huang Qiang, Tel/Fax: +86-791-83828176;E-mail: qiang-huang@live.com.

Foundation item: Supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32060778) and by the Initiation Funding of Jiangxi Agricultural University (050014/923230722)

Abstract: Nosemosis is an infectious disease caused by Nosema ceranae, which infects honey bees globally. Nosema ceranae infection led to premature aging, decreased nursing and productivity, as well as fecundity. Under extreme circumstances, the infection caused colony collapses. In this study, we summarized the etiology, epidemiology and the control methods of Nosema ceranae in the last ten years. This study aims to improve the understanding of Nosema ceranae biology and provide new insights for the parasite control.

Keywords: Nosema ceranaeepidemiological analysisprevention and control methodshoneybee

在过去半个世纪里,全世界作物种植面积增加了约25%,其中相当多一部分是依靠授粉的虫媒花植物[1]。蜜蜂是全球范围内最重要的授粉者[2–3],也是目前唯一被人类大规模饲养,并能够在短时期内完成对密集开花的高产作物进行授粉的昆虫[4]。蜂群的快速衰减为农业生产带来严重威胁[5–6],这一点在北美的表现尤为突出[7–8]。造成蜂群数量下降的因素是多方面的,除农药的使用、环境的变化所带来的不利因素外,越来越多的研究证实寄生虫及病原体的感染是造成蜂群死亡的主要因素[9–11]。东方蜜蜂微孢子虫病是由东方蜜蜂微孢子虫引起的一种蜜蜂消化道传染病[12],主要通过被污染的水源和食物进行蜂群内及蜂群间的互相传播[13–15]。蜜蜂在感染后表现出定向和归巢能力降低、加速老龄化、蜂群抵抗力和哺育能力下降、采集蜂过早死亡[16–20]等现象。

1996年,东方蜜蜂微孢子虫首次在北京的东方蜜蜂肠道内被发现和命名[21]。2003年以来,美国、巴西、墨西哥、芬兰、澳大利亚及非洲等多个国家或地区均有东方蜜蜂微孢子虫感染蜜蜂的报道[22–26],此外熊蜂(Bombus)等多个蜂种均可作为东方蜜蜂微孢子虫的寄生宿主[15]。

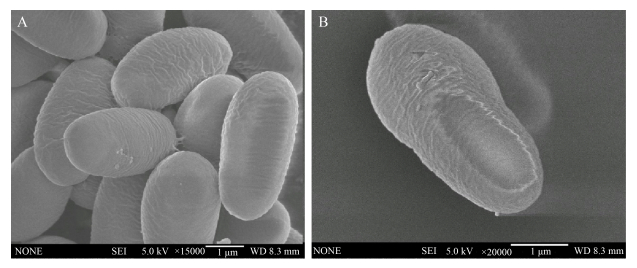

1 病原学 东方蜜蜂微孢子虫病的病原属于微孢子虫科(Nosematidae)微孢子虫属(Nosema)的成员,被命名为东方蜜蜂微孢子虫。东方蜜蜂微孢子虫属于单细胞真核生物,不能在宿主细胞外繁殖,没有经典的线粒体,但携带有由线粒体衍生的细胞器,称为线粒体残迹(mitosome),通过利用宿主的能量物质完成自身的快速繁殖[27]。成熟的孢子为椭圆形,可在400倍光学显微镜下观察到,其平均大小为4.5 μm×2.4 μm,孢壁主要成分为几丁质和糖蛋白[28]。在扫描电镜下可以观察到东方蜜蜂微孢子虫孢壁上具有粗糙褶皱(图 1);透射电镜下可测得孢壁厚度为137–183 nm,由内向外可分为刺突状外层、电子透明薄层和纤维性内层,其中电子透明层较厚,从孢壁整体上看前端孢壁较薄,只有约36 nm,是孢子抛出极丝的位置,孢子前端具有固根盘结构,后端是具有空泡结构的后极泡,内质网在核的两端依次缠绕。极丝具有4层结构,在核外盘绕20–23圈,螺旋倾角为55°–60°[29]。

|

| 图 1 扫描电镜下东方蜜蜂微孢子虫的外部形态特征[29] Figure 1 The external morphology of Nosema ceranae by scanning electronic micrographs[29]. A: external morphology of multiple spores; B: external morphology of a single spore. |

| 图选项 |

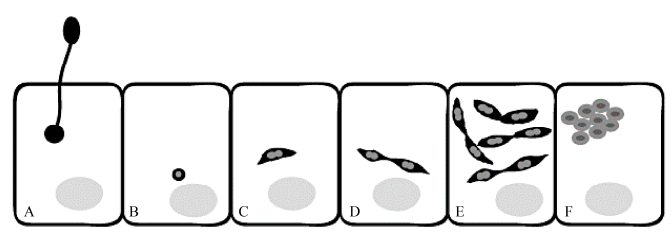

永久的蜜蜂细胞培养系和蜜蜂病原体细胞的培养模型的缺乏严重制约了蜜蜂病原体与靶细胞之间的分子和细胞相互作用的研究进展[12]。为了克服这一障碍,Gisder等基于从吉普赛蛾卵巢建立的异源鳞翅目细胞系IPL-LD-65Y开发了专性细胞内蜜蜂病原体东方蜜蜂微孢子虫的细胞培养模型,为东方蜜蜂微孢子虫在蜜蜂细胞内繁殖周期提供了新的见解[12, 30]。与IPL-LD-65Y悬浮细胞共同孵育萌发的东方蜜蜂微孢子虫显示,萌发的孢子挤出极管,从远处击中目标细胞,然后将孢子质注入宿主细胞[31]。此后不久,感染细胞中的孢子质变为球形小体。对细胞内生命周期的时程分析表明:接种东方蜜蜂微孢子虫16 h后,注入的孢子质发育成东方蜜蜂微孢子虫的营养阶段,形成一个纺锤形分生组织。在随后的4 h,第一对纺锤形的分生组织开始出现。然后,这些纺锤形分生孢子成倍增加,直到第一个凝聚结构的形成。在感染细胞的48–72 h期间可以检测到发育成初生孢子和许多对纺锤形分生粒。初生孢子为圆形,而不是环境孢子的椭圆形[32],成熟孢子在感染细胞大约96 h后可以检测到(图 2)。

|

| 图 2 东方蜜蜂微孢子虫繁殖周期示意图[12] Figure 2 Schematic representation of the early events in the life cycle of Nosema ceranae[12]. A: membrane of the target cell followed by injection of the sporoplasm into the host cell; B: the sporoplasm appears as small spherical body in the host cell; C: develops into a spindle-shaped meront; D: which begins to divide giving rise to paired meronts; E: these pairs of meronts then undergo several rounds of cell division; F: they separate and develop into round to oval sporonts, which are condensed and characterized by a thickened plasma membrane. |

| 图选项 |

2 流行病学 2.1 易感动物 东方蜜蜂微孢子虫具有感染蜂种多、范围广的特点[15]。成年蜜蜂在各阶段对本病均易感。在同一蜂群中,新出房蜜蜂体内几乎无东方蜜蜂微孢子虫,采集蜂感染量最高,其次为哺育蜂[33]。利用人工方法对蜜蜂接种东方蜜蜂微孢子虫,结果表明,蜜蜂在出房1 d内最易感染东方蜜蜂微孢子虫,在出房5 d后对感微孢子虫染不敏感[34]。东方蜜蜂微孢子虫对蜜蜂来说是具有高度特异性的消化道寄生物,在感染后的第3天,利用400倍光学显微镜可在中肠上皮细胞、排泄物和分泌物中观察到成熟的孢子[18]。

2.2 传染源及传播途径 东方蜜蜂微孢子虫主要通过直接接触传播和间接接触传播两个途径。在蜂群内部,由于蜜蜂具有交哺的生物学特性,患病蜂在交哺行为发生过程中将东方蜜蜂微孢子虫传给了健康蜜蜂[35–36]。在外界环境中,东方蜜蜂微孢子虫通过被病蜂排泄物、分泌物污染的蜂粮和水源进行传播。此外Sulborska等[37]曾报道,干燥的粪便及某些生物气溶胶内携带的东方蜜蜂微孢子虫可以借助空气进行传播。显然在饲养管理中不恰当的并群和盗蜂现象的产生会加速东方蜜蜂微孢子虫在蜂群间的传播。卫生条件差、蜂群营养状况不佳等不良的饲养管理条件会提高该病的发病率和死亡率。一般情况下,弱群在感染后所表现出的危害性比强群更明显,这主要是因为弱群抵抗力和免疫力更弱。

2.3 流行特点 Martin-Hernandez[38]在2005年对西班牙感染东方蜜蜂微孢子虫的蜂群感染率进行统计分析,结果显示东方蜜蜂微孢子虫的感染无季节特异性。但在2008年,Higes等[39]对采集蜂和哺育蜂的感染率以及蜜蜂中肠内孢子载量进行检测,发现蜂群在感染后第二年秋季,微孢子感染率和蜜蜂中肠内孢子载量达到最高,随后出现蜂群衰竭症状。2009–2010年间,Traver等[40]对弗吉尼亚州西南部蜂群内采集蜂的感染率和孢子载量结合qPCR的方法进行分析,结果表明东方蜜蜂微孢子虫的感染在春末夏初达到顶峰,其余时间有所下降,这与Gisder等[41]在德国的实验结果相似,导致这种差异的原因可能与取样时间、测量指标、当地环境和气候有关。显然,东方蜜蜂微孢子虫的发病特点是复杂的,评估感染水平的季节性变化需要从多个方面进行综合考量。

3 临床症状 东方蜜蜂微孢子虫在感染蜂群后,主要经历无症状阶段、取代阶段、假恢复阶段和蜂群衰竭四个阶段[42]。无症状阶段主要在感染的第一个春季到秋季,蜂群感染后外观不明显,低于60%的采集蜂被感染,单只蜜蜂中肠内东方蜜蜂微孢子载量低于100万个。取代阶段是指由于蜜蜂出房前体内几乎不含有孢子,蜂巢内工蜂可以培育较多幼虫,使群势重新恢复。假恢复阶段一般发生在第二年春季到秋季,由于外界蜜源充足,蜂群略有恢复,但整体上感染开始向巢内蜂移动。最后是蜂群衰竭阶段,蜂群内蜜蜂数量突然下降到60%左右,采集蜂东方蜜蜂微孢子感染率大于65%,哺育蜂孢子感染率大于40%,单只蜜蜂中肠内孢子载量大于100万个。若发生在寒冷季节,单只蜜蜂中肠内孢子载量可超过1000万个,蜂王和幼虫也会因感染东方蜜蜂微孢子虫而死亡[39]。

蜜蜂个体在感染东方蜜蜂微孢子虫后,免疫防御、新陈代谢和营养消化功能受到扰乱。东方蜜蜂微孢子虫会导致被感染蜜蜂免疫受到抑制,抗菌肽Abaecin、Apidaecin、Hymenoptaecin和Defensin1的基因表达水平显著降低[43–44],由于其发病过程缓慢而漫长,随时间推移逐渐显现下痢、腹部膨大、中肠显白色等明显症状。东方蜜蜂微孢子虫能够诱导中肠和大脑中与营养代谢和激素分泌相关的基因表达的变化[45–47]。孢子从蜜蜂中肠中获得能量,损害蜜蜂上皮细胞,并随着感染的时间在数量上不断增加,这增加了蜜蜂的氧化应激[18, 45–46],同时咽下腺等与营养敏感相关的结构和功能发生变化[48–51]。在中肠蛋白质组中,与能量和蛋白质的代谢、抗氧化防御有关的结构也发生了改变[52–53]。因此受感染蜜蜂表现出明显的饥饿感和对蔗糖敏感度的增加,并且不愿意与其他个体分享食物[17, 19]。同时被感染蜜蜂会出现早熟觅食、恶劣天气条件下外出觅食和盗蜂现象,这些非正常的觅食行为不仅降低了蜜蜂的采集能力,更会使大量蜜蜂无法返回蜂箱,蜂群整体年龄结构发生改变,并可能进一步导致蜂群的损失[16, 39, 54–58]。

4 病理变化 东方蜜蜂微孢子虫只在细胞质中发育繁殖而不入侵细胞核。正常蜜蜂中肠上皮细胞的细胞核呈规则的圆球状,而感染东方蜜蜂微孢子虫后,中肠细胞的细胞膜完全被破坏,细胞间界限不明显;细胞质中存在大量处于不同发育阶段的孢子;随后细胞核开始膨大,并因成熟孢子的挤压而呈现不规则形状,细胞核内染色质凝集,核膜略有消融;正常中肠细胞中的线粒体呈长椭圆形,板层状嵴突与线粒体长轴垂直,感染东方蜜蜂微孢子虫后,线粒体变小,嵴增宽且排列方向改变,有些线粒体嵴减小甚至消融。正常中肠细胞中的粗面内质网排列整齐,多呈密集平行排列的扁平囊状,核糖体附着在膜外表面,感染东方蜜蜂微孢子虫后,粗面内质网散乱于细胞质中,排列紊乱,甚至被挤压成碎片直至解体[29]。利用传统的HE对蜜蜂中肠切片进行染色,发现被感染的中肠上皮细胞胞浆扩张,胞核颜色鲜艳,顶端移位。细胞腔内常残留充满成熟孢子的分泌球和游离成熟孢子。此外,周围经常出现断裂的细胞膜。某些粪便小球内含有许多孢子,周围环绕着营养物质和花粉[59],在回肠内未见明显病变。

5 诊断 通过流行病学和特征性临床症状,可以作出初步诊断,确诊需要通过形态学检测、免疫学检测和分子生物学诊断,主要包括东方蜜蜂微孢子虫的分离鉴定、涂片镜检、单克隆抗体制备、PCR检测等。并注意与蜜蜂微孢子病的鉴别诊断。

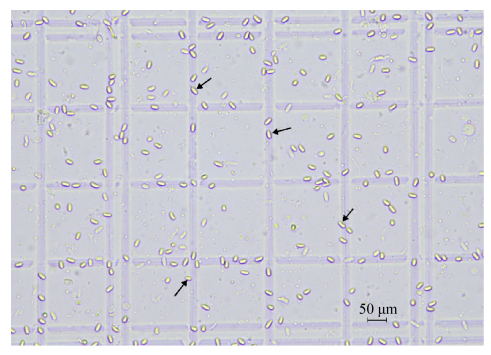

5.1 形态学检测 随机抓取20只疑似患有东方蜜蜂微孢子虫的蜜蜂,解剖其中肠于1.5 mL EP管中,加入500 μL双蒸水,利用研磨棒进行研磨。取悬浮液20 μL于载玻片,盖上盖玻片,在400倍光学显微镜下进行镜检(图 3)。若观察到有椭圆形,具有折光性的个体,即可确诊微孢子的存在。

|

| 图 3 400倍光学显微镜下东方蜜蜂微孢子虫 Figure 3 Nosema ceranae under light microscope (400 times). |

| 图选项 |

5.2 免疫学检测 通过对东方蜜蜂微孢子虫特定的SWP-32抗体进行酶联免疫吸附实验(Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay,ELISA),可以确定目的蛋白或者激素的存在,并通过分光光度计和标准样对检测样品的孢子含量和感染程度进行定性[60]。

5.3 分子生物学诊断 东方蜜蜂微孢子虫具有较厚的孢子壁,需要采用玻璃珠破碎法或液氮研磨法提取模板DNA,其基因组全长约7.86 Mb[61],可用于多重PCR。通过正向引物(5′-CGGCGACGATGTGATATGAA AATATTAA-3′)和反向引物(5′-CCCGGTCATTC TCAAACAAAA-AACCG-3′)进行扩增。PCR反应程序为94 ℃ 10 s,62 ℃ 15 s,72 ℃ 30 s,25个循环,每个连续循环加2 s的延伸循环,最后在72 ℃下延伸7 min。其最终产物为218 bp,通过琼脂糖凝胶电泳可进行检测[62]。

6 防治方法 在现有研究中,尚未发现一种高效抑制或杀灭东方蜜蜂微孢子虫、成本低廉和无残留的药物和方法。但在营养防治、基因水平防治、天然植物提取物防治和微生物防治等方面已有许多探索。

6.1 抗生素 烟曲霉素早在1949年从真菌烟曲霉(Aspergillus Fumigatus)发酵液中提取出来,也是目前在美国唯一经过药品注册和认证的对微孢子感染有效的药物[63]。烟曲霉素在美国养蜂业中被应用于控制蜜蜂微孢子虫已有50多年历史,3%的烟曲霉素对东方蜜蜂微孢子虫也具有抑制作用[64–65]。烟曲霉素通过抑制东方蜜蜂微孢子虫蛋氨酸氨基肽酶2 (MetAP2)的表达,干扰东方蜜蜂微孢子虫行使正常细胞功能所必需的蛋白质修饰来发挥功能[66]。但最新研究表明,烟曲霉素具有相当强烈的毒性,会导致蜜蜂染色体畸变和下咽腺超微结构的改变[63],因此烟曲霉素在美洲以外的许多国家被禁止使用。

6.2 肠道微生物对微孢子的感染和预防具有积极意义 随着测序技术的逐渐成熟,测序的深度在不断提高,而测序成本却大幅下降[67],人们对肠道微生物的研究日益增多,有研究发现,当病原体侵染宿主时,微生物群落会产生戏剧性的反应,通过改善蜜蜂肠道微生态环境,对提高蜜蜂对病原微生物的抵抗力具有重要作用[68]。东方蜜蜂微孢子从侵染宿主细胞到孢子成熟大约需要4 d时间[12],在这一过程中,东方蜜蜂微孢子虫会不可避免地受到肠道微生物的影响。

在成年蜜蜂身上已经确定了8个核心菌群,包括Gilliamella apicola、Frischella perrara、Snodgrassella alvi、Lactobacillus mellis、Lactobacillus Firm5、Bifidobacterium asteroides、Bartonellaceae和Acetobacteraceae[69]。这8个核心菌群以及一些更低频的微生物可能会参与到蜜蜂肠道对花粉和蜂蜜的消化,宿主并未提供营养[70]。研究表明,当肠道微生物受到抗生素干扰时,蜜蜂更容易受到东方蜜蜂微孢子虫及其他病原体的感染[71–72]。Frischella perrara会触发蜜蜂的黑化反应,刺激宿主产生具有细胞毒性的醌类中间产物,醌类中间产物会聚合成黑色素沉积到入侵的病原体周围,起到隔离杀死病原体的作用[73]。乳酸菌作为饲料添加剂对东方蜜蜂微孢子的感染具有抑制作用[74]。Szyma?等[75]在人工合成花粉中添加Biogen及Trilac两种益生菌制剂提高了蜜蜂中肠内围食膜的存在。而围食膜具有保护中肠上皮细胞和有助于食物消化吸收的功能,从而提高了蜜蜂肠道的抵抗力。Rubanov等[76]对感染东方微孢子与未感染微孢子蜜蜂体内肠道菌群进行比对,发现两个特定的Gilliamella菌株与东方蜜蜂微孢子虫的感染强度呈正相关。但也有研究发现,共生菌Gilliamella Apicola和Snogrsella Alvi具有提高宿主对食物消化能力和病原体防御的功能,这可能与不同菌株之间的序列差异导致的功能变异有关[77–78]。

显然,蜜蜂和肠道微生物会对东方蜜蜂微孢子虫的感染作出反应,这为东方蜜蜂微孢子虫的防治提供了一种十分重要的非化学手段[79],但不适当的益生菌制剂补充也可能导致肠道微生物的失调和对病原微生物易感性的增加[80],因此利用益生菌防治东方蜜蜂微孢子感染仍有巨大的研究空间和价值。

6.3 天然提取物对微孢子的抑制作用 天然提取物对东方蜜蜂微孢子虫的抑制作用也同样受到人们的广泛研究。各种天然提取物已被证明在饲喂蜜蜂治疗东方蜜蜂微孢子虫感染后,可以提高蜜蜂的存活率和降低孢子的载量[81–85]。蜂胶是工蜂通过采集树脂,并混入上颚腺和蜡腺分泌物形成的产物[86],是蜜蜂建造巢房的主要物质,也是在传统中医药中重要的材料。蜂胶提取物在抗菌抑菌[87]、解毒、杀灭病原微生物[88]等方面的功效已被证实。Alessandra等[89]试验证明蜂胶对东方蜜蜂微孢子虫的感染具有抑制作用,但高浓度的蜂胶对蜜蜂存在显著的致死作用,这可能与蜂胶内所含有的一些多酚类物质有关。莱菔硫烷、香芹酚、柚皮素、1%浓度的牛膝提取液被证明对东方蜜蜂微孢子虫的感染和发育具有抑制作用,但与蜂胶一样存在对蜜蜂致死的作用[83, 90]。

从蜂胶和植物中所获得的粗提取物化学成分往往是复杂且未知的,提取物成分的降解及变质等会影响天然提取物对东方蜜蜂微孢子的防治效果。利用天然提取物来防治东方蜜蜂微孢子的生产过程必须高度标准化,才能保证治疗效果[91]。虽然天然植物提取物还存在一定的缺陷,但从药物残留和耐药性方面考虑,利用植物提取物治疗或预防东方蜜蜂微孢子虫的感染仍是当下研究的一大热点。

6.4 RNA干扰技术对微孢子的防治效果 RNA干扰(RNAi)是一种由双链RNA (dsRNA)引起的转录后基因沉默的自然机制,双链RNA在序列上与沉默的基因同源,已被用于操纵几种生物中的基因表达[92]。利用RNA干扰技术来进行基因敲除的方法已被广泛用于控制害虫数量、控制昆虫病原性疾病和研究特定基因在许多昆虫物种中的功能作用[93–95]。对意大利蜜蜂的完整基因组分析揭示了该物种中存在与RNA沉默有关的遗传机制。东方蜜蜂微孢子虫和蜜蜂微孢子虫基因组的可获得性以及对这2个微孢子虫物种的比较基因组分析[96],为蜜蜂宿主细胞内寄生虫的粘附、入侵、免疫逃避、定殖和复制有关的毒力因子的鉴定提供了条件。对东方蜜蜂微孢子虫在感染过程中的生活史和致病性了解的提高,使我们能够利用RNA干扰技术来治疗蜜蜂微孢子病。现有研究表明,沉默微孢子虫毒力因子和宿主免疫抑制基因可以减少寄生虫载量,激活蜜蜂免疫反应,并改善受感染蜜蜂的整体健康[97–98]。

极管是微孢子穿透宿主细胞膜,将具有感染性孢子质传递到宿主细胞内,完成对宿主侵袭感染的重要结构。富含脯氨酸的极管蛋白1、富含赖氨酸的极管蛋白2和分子量大于135 kDa的极管蛋白3是已知的组成孢子极管的主要蛋白。Rodríguez-García等以蜜蜂微孢子同源、分子量大于13 kDa的极管蛋白3为靶基因,饲喂极管蛋白3区域所对应的dsRNA,可以使感染东方蜜蜂微孢子虫的蜜蜂在处理后的第10天,极管蛋白3表达下调,蜜蜂体内微孢子虫的载量明显降低,与免疫相关的Apidaecin、Abaecin、Hymenoptaecin和defensin-1 4个基因表达发生上调[97, 99]。

Dicer基因对细胞核酸内切酶具有广泛的调控作用,Huang等[100]利用小RNA干扰技术,通过抑制微孢子Dicer基因的表达,降低了70%微孢子的数量,与细胞增殖相关基因受到抑制,说明微孢子繁殖受到抑制。同时,mucin-2-like在Dicer基因受到抑制后显著上调,增强了中肠黏膜上皮细胞对微孢子的抵抗力。结果表明Dicer可调控东方蜜蜂微孢子虫的繁殖。

通过抑制宿主免疫抑制基因表达、提高蜜蜂抵抗力也是治疗和预防东方蜜蜂微孢子虫感染的重要手段。研究表明,Wnt通路对昆虫Toll通路上免疫基因的表达具有抑制作用[101],裸露角质层基因(naked cuticle,nkd)是Wnt通路上的重要一员[102]。Li等[103]通过沉默蜜蜂nkd基因,上调了Apidaecin、Abaecin、Hymenoptaecin和defensin-1 4个免疫基因的表达,进而降低了宿主体内东方蜜蜂微孢子虫的载量,延长了蜜蜂寿命。这一结果清晰地表明,沉默宿主nkd基因的表达可以激活宿主的免疫反应,抑制东方蜜蜂微孢子虫的繁殖,改善蜜蜂的整体健康状况。

6.5 抗东方蜜蜂微孢子虫蜂王的培育 实践证明,选择性繁殖、更换蜂王等蜂群管理手段对蜂群的多发性疾病具有很好的预防和缓解作用。通过人工选育的方法,培育出对微孢子感染具有抗性或耐性的蜂种,所产生的意义是长远和重大的。这不仅减少了蜂农在时间和金钱方面的投入,更减少了耐药性和药物残留发生的可能性。在丹麦,蜂农通过20多年的选育,已经培育出一种对东方蜜蜂微孢子虫具有抗性的蜂种[104]。在俄罗斯[105]、乌拉圭[106]也有报道发现对东方蜜蜂微孢子虫具有天然抗性的蜂种。这表明,在蜜蜂群体中足够的遗传变异可以产生对东方蜜蜂微孢子虫具有抗性的品种。

通过以上研究可知,通过药物防治东方蜜蜂微孢子虫其效果是相对有限的,且目前尚无法律允许的药物用于养蜂业的生产。现阶段天然植物提取物、蜂胶提取并没有实现批量生产,且存在使用浓度与蜜蜂致死率的矛盾尚待解决。对于蜜蜂肠道微生物和营养状况的研究,证实了提高蜜蜂自身抵抗力对抑制东方蜜蜂微孢子虫的积极意义。RNA干扰技术则存在着成本高和临床应用繁琐的缺点。在生产实践中加强蜂群的饲养管理,选择地势较高、阳光充足和较为安静的环境,饲喂干净和优质的蜂粮,提高蜂群自身抵抗力是防治东方蜜蜂微孢子虫的有效途径。

7 展望 在东方蜜蜂微孢子虫首次发现的10年后,就有研究表明在美国和欧洲先后暴发的蜜蜂崩溃综合症(colony collapse disorder,CCD)与东方蜜蜂微孢子虫存在间接联系[39]。2013年,张建燕等[107]对我国16个主要养蜂地区的蜜蜂微孢子感染情况进行了调查和检测,在68份检测样品中,东方蜜蜂微孢子在西方蜜蜂的体内感染率高达98.5%。东方蜜蜂微孢子虫在我国以及世界范围内已广泛流行,但在现有阶段,鲜有资料就东方蜜蜂微孢子传染病学特点进行总结和报道。

东方蜜蜂微孢子虫病的发生和流行是由传染源、传播途径和易感动物相互联系、相互作用引起的复杂过程,从传染病学角度做好东方蜜蜂微孢子虫病的防治工作具有重要意义。在综合防治东方蜜蜂微孢子虫病时,需要果断采取消灭传染源、切断传播途径和保护易感动物的措施,以此阻止传染病流行发展过程中3个必要因素之间的相互联系。在现阶段,人们已从病原学特点、临床特征、诊断方法及分子生物学水平对东方蜜蜂微孢子虫病进行了解,在治疗手段方面经历了从单纯的利用抗生素治疗到利用肠道微生物、天然提取物、RNA干扰及育种技术对蜜蜂进行预防和治疗的探索,但在切断东方蜜蜂微孢子虫的传播途径方面仍然需要进行大量的探索和研究。

通过确定东方蜜蜂微孢子虫的感染特征以及开发出一套预防和治疗东方蜜蜂微孢子虫病的治疗方法意义重大。对东方蜜蜂微孢子虫的治疗和控制不仅可以降低蜂群的损失,更能使其他野生授粉者受益[108–110]。蜜蜂与东方蜜蜂微孢子虫之间的研究也可能为人类微孢子虫病的研究和治疗提供借鉴和模型[111],通过对蜜蜂病理学的深入研究为人类的医疗实践提供重要的参考。

References

| [1] | Magrach A, González-Varo JP, Boiffier M, Vilà M, Bartomeus I. Honeybee spillover reshuffles pollinator diets and affects plant reproductive success. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 2017, 1(9): 1299-1307. |

| [2] | Kleijn D, Winfree R, Bartomeus I, Carvalheiro LG, Henry M, Isaacs R, Klein AM, Kremen C, Rader R, Ricketts TH, Williams NM, Adamson NL, Ascher JS, Báldi A, Batáry P, Benjamin F, Biesmeijer JC, Blitzer EJ, Bommarco R, Brand MR, Bretagnolle V, Button L, Cariveau DP, Chifflet R, Colville JF, Danforth BN, Elle E, Garratt MPD, Herzog F, Holzschuh A, Howlett BG, Jauker F, Jha S, Knop E, Krewenka KM, le Féon V, Mandelik Y, May EA, Park MG, Pisanty G, Reemer M, Riedinger V, Rollin O, Rundl?f M, Sardi?as HS, Scheper J, Sciligo AR, Smith HG, Steffan-Dewenter I, Thorp R, Tscharntke T, Verhulst J, Viana BF, Vaissière BE, Veldtman R, Ward KL, Westphal C, Potts SG. Delivery of crop pollination services is an insufficient argument for wild pollinator conservation. Nature Communications, 2015, 6: 7414. DOI:10.1038/ncomms8414 |

| [3] | Kennedy CM, Lonsdorf E, Neel MC, Williams NM, Ricketts TH, Winfree R, Bommarco R, Brittain C, Burley AL, Cariveau D, Carvalheiro LG, Chacoff NP, Cunningham SA, Danforth BN, Dudenh?ffer JH, Elle E, Gaines HR, Garibaldi LA, Gratton C, Holzschuh A, Isaacs R, Javorek SK, Jha S, Klein AM, Krewenka K, Mandelik Y, Mayfield MM, Morandin L, Neame LA, Otieno M, Park M, Potts SG, Rundl?f M, Saez A, Steffan-Dewenter I, Taki H, Viana BF, Westphal C, Wilson JK, Greenleaf SS, Kremen C. A global quantitative synthesis of local and landscape effects on wild bee pollinators in agroecosystems. Ecology Letters, 2013, 16(5): 584-599. DOI:10.1111/ele.12082 |

| [4] | Rader R, Howlett BG, Cunningham SA, Westcott DA, Newstrom-Lloyd LE, Walker MK, Teulon DAJ, Edwards W. Alternative pollinator taxa are equally efficient but not as effective as the honeybee in a mass flowering crop. Journal of Applied Ecology, 2009, 46(5): 1080-1087. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2664.2009.01700.x |

| [5] | Klein AM, Vaissière BE, Cane JH, Steffan-Dewenter I, Cunningham SA, Kremen C, Tscharntke T. Importance of pollinators in changing landscapes for world crops. Proceedings Biological Sciences, 2007, 274(1608): 303-313. |

| [6] | Calderone NW. Insect pollinated crops, insect pollinators and US agriculture: trend analysis of aggregate data for the period 1992-2009. PLoS ONE, 2012, 7(5): e37235. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0037235 |

| [7] | Van Engelsdorp D, Hayes J Jr, Underwood RM, Pettis J. A survey of honey bee colony losses in the US, fall 2007 to spring 2008. PLoS ONE, 2008, 3(12): e4071. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0004071 |

| [8] | Vanengelsdorp D, Evans JD, Saegerman C, Mullin C, Haubruge E, Nguyen BK, Frazier M, Frazier J, Cox-Foster D, Chen YP, Underwood R, Tarpy DR, Pettis JS. Colony collapse disorder: a descriptive study. PLoS ONE, 2009, 4(8): e6481. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0006481 |

| [9] | Goulson D, Nicholls E, Botías C, Rotheray EL. Bee declines driven by combined stress from parasites, pesticides, and lack of flowers. Science, 2015, 347(6229): 1255957. DOI:10.1126/science.1255957 |

| [10] | Cox-Foster DL, Conlan S, Holmes EC, Palacios G, Evans JD, Moran NA, Quan PL, Briese T, Hornig M, Geiser DM, Martinson V, VanEngelsdorp D, Kalkstein AL, Drysdale A, Hui J, Zhai JH, Cui LW, Hutchison SK, Simons JF, Egholm M, Pettis JS, Lipkin WI. A metagenomic survey of microbes in honey bee colony collapse disorder. Science, 2007, 318(5848): 283-287. DOI:10.1126/science.1146498 |

| [11] | Dainat B, VanEngelsdorp D, Neumann P. Colony collapse disorder in Europe. Environmental Microbiology Reports, 2012, 4(1): 123-125. DOI:10.1111/j.1758-2229.2011.00312.x |

| [12] | Gisder S, M?ckel N, Linde A, Genersch E. A cell culture model for Nosema ceranae and Nosema apis allows new insights into the life cycle of these important honey bee-pathogenic microsporidia. Environmental Microbiology, 2011, 13(2): 404-413. DOI:10.1111/j.1462-2920.2010.02346.x |

| [13] | Fenoy S, Rueda C, Higes M, Martín-Hernández R, del Aguila C. High-level resistance of Nosema ceranae, a parasite of the honeybee, to temperature and desiccation. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2009, 75(21): 6886-6889. DOI:10.1128/AEM.01025-09 |

| [14] | Higes M, Martin-Hernandez R, Meana A. Nosema ceranae in Europe: an emergent type C nosemosis. Apidologie, 2010, 41(3): 375-392. DOI:10.1051/apido/2010019 |

| [15] | Graystock P, Ng WH, Parks K, Tripodi AD, Mu?iz PA, Fersch AA, Myers CR, McFrederick QS, McArt SH. Dominant bee species and floral abundance drive parasite temporal dynamics in plant-pollinator communities. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 2020, 4(10): 1358-1367. |

| [16] | Goblirsch M, Huang ZY, Spivak M. Physiological and behavioral changes in honey bees (Apis mellifera L.) induced by Nosema ceranae infection. PLoS ONE, 2013, 8(3): e58165. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0058165 |

| [17] | Naug D, Gibbs A. Behavioral changes mediated by hunger in honeybees infected with Nosema ceranae. Apidologie, 2009, 40(6): 595-599. DOI:10.1051/apido/2009039 |

| [18] | Higes M, García-Palencia P, Martín-Hernández R, Meana A. Experimental infection of Apis mellifera honeybees with Nosema ceranae (Microsporidia). Journal of Invertebrate Pathology, 2007, 94(3): 211-217. DOI:10.1016/j.jip.2006.11.001 |

| [19] | Mayack C, Naug D. Energetic stress in the honeybee Apis mellifera from Nosema ceranae infection. Journal of Invertebrate Pathology, 2009, 100(3): 185-188. DOI:10.1016/j.jip.2008.12.001 |

| [20] | Paxton RJ, Klee J, Korpela S, Fries I. Nosema ceranae has infected Apis mellifera in Europe since at least 1998 and may be more virulent than Nosema apis. Apidologie, 2007, 38(6): 558-565. DOI:10.1051/apido:2007037 |

| [21] | Fries I, Feng F, da Silva A, Slemenda SB, Pieniazek NJ. Nosema ceranae n. sp. (Microspora, Nosematidae), morphological and molecular characterization of a microsporidian parasite of the Asian honey bee Apis cerana (Hymenoptera, Apidae).. European Journal of Protistology, 1936, 32(3): 356-365. |

| [22] | Klee J, Besana AM, Genersch E, Gisder S, Nanetti A, Tam DQ, Chinh TX, Puerta F, Ruz JM, Kryger P, Message D, Hatjina F, Korpela S, Fries I, Paxton RJ. Widespread dispersal of the microsporidian Nosema ceranae, an emergent pathogen of the western honey bee, Apis mellifera. Journal of Invertebrate Pathology, 2007, 96(1): 1-10. DOI:10.1016/j.jip.2007.02.014 |

| [23] | Chen YP, Evans JD, Smith IB, Pettis JS. Nosema ceranae is a long-present and wide-spread microsporidian infection of the European honey bee (Apis mellifera) in the United States. Journal of Invertebrate Pathology, 2008, 97(2): 186-188. DOI:10.1016/j.jip.2007.07.010 |

| [24] | Invernizzi C, Abud C, Tomasco IH, Harriet J, Ramallo G, Campá J, Katz H, Gardiol G, Mendoza Y. Presence of Nosema ceranae in honeybees (Apis mellifera) in Uruguay. Journal of Invertebrate Pathology, 2009, 101(2): 150-153. DOI:10.1016/j.jip.2009.03.006 |

| [25] | Stevanovic J, Stanimirovic Z, Genersch E, Kovacevic SR, Ljubenkovic J, Radakovic M, Aleksic N. Dominance of Nosema ceranae in honey bees in the Balkan countries in the absence of symptoms of colony collapse disorder. Apidologie, 2011, 42(1): 49. DOI:10.1051/apido/2010034 |

| [26] | Plischuk S, Martín-Hernández R, Prieto L, Lucía M, Botías C, Meana A, Abrahamovich AH, Lange C, Higes M. South American native bumblebees (Hymenoptera: Apidae) infected by Nosema ceranae (Microsporidia), an emerging pathogen of honeybees (Apis mellifera). Environmental Microbiology Reports, 2009, 1(2): 131-135. DOI:10.1111/j.1758-2229.2009.00018.x |

| [27] | Burri L, Williams BAP, Bursac D, Lithgow T, Keeling PJ. Microsporidian mitosomes retain elements of the general mitochondrial targeting system. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2006, 103(43): 15916-15920. DOI:10.1073/pnas.0604109103 |

| [28] | Huang WF, Jiang JH, Chen YW, Wang CH. A Nosema ceranae isolate from the honeybee Apis mellifera. Apidologie, 2007, 38(1): 30-37. DOI:10.1051/apido:2006054 |

| [29] | Qin HR, He SY, Wu J, Li JL. Pathogenic mechanism of Bombus patagiatus infected by Nosema ceranae. Scientia Agricultura Sinica, 2012, 45(22): 4697-4704. (in Chinese) 秦浩然, 和绍禹, 吴杰, 李继莲. 东方蜜蜂微孢子虫对密林熊蜂的致病机理. 中国农业科学, 2012, 45(22): 4697-4704. DOI:10.3864/j.issn.0578-1752.2012.22.016 |

| [30] | Goodwin RH, Tompkins GJ, McCawley P. Gypsy moth cell lines divergent in viral susceptibility. In Vitro, 1978, 14(6): 485-494. DOI:10.1007/BF02616088 |

| [31] | Ghosh K, Weiss LM. Molecular diagnostic tests for microsporidia. Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Infectious Diseases, 2009, 2009: 1-13. |

| [32] | De Graaf DC, De Raes H, Jacobs FJ. Spore dimorphism in Nosema apis (Microsporida, Nosematidae) developmental cycle. Journal of Invertebrate Pathology, 1994, 63(1): 92-94. DOI:10.1006/jipa.1994.1015 |

| [33] | Li WF, Evans JD, Li JH, Su SK, Hamilton M, Chen YP. Spore load and immune response of honey bees naturally infected by Nosema ceranae. Parasitology Research, 2017, 116(12): 3265-3274. DOI:10.1007/s00436-017-5630-8 |

| [34] | Urbieta-Magro A, Higes M, Meana A, Barrios L, Martín-Hernández R. Age and method of inoculation influence the infection of worker honey bees (Apis mellifera) by Nosema ceranae. Insects, 2019, 10(12): E417. DOI:10.3390/insects10120417 |

| [35] | Smith ML. The honey bee parasite Nosema ceranae: transmissible via food exchange?. PLoS ONE, 2012, 7(8): e43319. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0043319 |

| [36] | Martín-Hernández R, Botías C, Barrios L, Martínez-Salvador A, Meana A, Mayack C, Higes M. Comparison of the energetic stress associated with experimental Nosema ceranae and Nosema apis infection of honeybees (Apis mellifera). Parasitology Research, 2011, 109(3): 605-612. DOI:10.1007/s00436-011-2292-9 |

| [37] | Sulborska A, Horecka B, Cebrat M, Kowalczyk M, Skrzypek TH, Kazimierczak W, Trytek M, Borsuk G. Microsporidia Nosema spp.-obligate bee parasites are transmitted by air. Scientific Reports, 2019, 9: 14376. DOI:10.1038/s41598-019-50974-8 |

| [38] | Martín-Hernández R, Meana A, Prieto L, Salvador AM, Garrido-Bailón E, Higes M. Outcome of colonization of Apis mellifera by Nosema ceranae. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2007, 73(20): 6331-6338. DOI:10.1128/AEM.00270-07 |

| [39] | Higes M, Martín-Hernández R, Botías C, Bailón EG, González-Porto AV, Barrios L, del Nozal MJ, Bernal JL, Jiménez JJ, Palencia PG, Meana A. How natural infection by Nosema ceranae causes honeybee colony collapse. Environmental Microbiology, 2008, 10(10): 2659-2669. DOI:10.1111/j.1462-2920.2008.01687.x |

| [40] | Traver BE, Fell RD. Prevalence and infection intensity of Nosema in honey bee (Apis mellifera L.) colonies in Virginia.. Journal of Invertebrate Pathology, 2011, 107(1): 43-49. DOI:10.1016/j.jip.2011.02.003 |

| [41] | Gisder S, Hedtke K, M?ckel N, Frielitz MC, Linde A, Genersch E. Five-year cohort study of Nosema spp. in Germany: does climate shape virulence and assertiveness of Nosema ceranae? Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2010, 76(9): 3032-3038. |

| [42] | Huang WC. Nosema ceranae. Journal of Bee, 2008, 28(7): 11-12. (in Chinese) 黄文诚. 东方蜜蜂微孢子虫. 蜜蜂杂志, 2008, 28(7): 11-12. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1003-9139.2008.07.023 |

| [43] | Antúnez K, Martín-Hernández R, Prieto L, Meana A, Zunino P, Higes M. Immune suppression in the honey bee (Apis mellifera) following infection by Nosema ceranae (Microsporidia). Environmental Microbiology, 2009, 11(9): 2284-2290. DOI:10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.01953.x |

| [44] | Chaimanee V, Chantawannakul P, Chen YP, Evans JD, Pettis JS. Differential expression of immune genes of adult honey bee (Apis mellifera) after inoculated by Nosema ceranae. Journal of Insect Physiology, 2012, 58(8): 1090-1095. DOI:10.1016/j.jinsphys.2012.04.016 |

| [45] | Holt HL, Aronstein KA, Grozinger CM. Chronic parasitization by Nosema microsporidia causes global expression changes in core nutritional, metabolic and behavioral pathways in honey bee workers (Apis mellifera). BMC Genomics, 2013, 14: 799. DOI:10.1186/1471-2164-14-799 |

| [46] | Mayack C, Natsopoulou ME, McMahon DP. Nosema ceranae alters a highly conserved hormonal stress pathway in honeybees. Insect Molecular Biology, 2015, 24(6): 662-670. DOI:10.1111/imb.12190 |

| [47] | McDonnell CM, Alaux C, Parrinello H, Desvignes JP, Crauser D, Durbesson E, Beslay D, Le Conte Y. Ecto- and endoparasite induce similar chemical and brain neurogenomic responses in the honey bee (Apis mellifera). BMC Ecology, 2013, 13(1): 1-15. DOI:10.1186/1472-6785-13-1 |

| [48] | Wang DR, Moeller FE. Histological comparisons of the development of hypopharyngeal glands in healthy and Nosema-infected worker honey bees. Journal of Invertebrate Pathology, 1969, 14(2): 135-142. DOI:10.1016/0022-2011(69)90098-6 |

| [49] | Alaux C, Brunet JL, Dussaubat C, Mondet F, Tchamitchan S, Cousin M, Brillard J, Baldy A, Belzunces L P, Le Conte Y. Interactions between Nosema microspores and a neonicotinoid weaken honeybees (Apis mellifera). Environmental Microbiology, 2010, 12(3): 774-782. DOI:10.1111/j.1462-2920.2009.02123.x |

| [50] | Corby-Harris V, Meador CAD, Snyder LA, Schwan MR, Maes P, Jones BM, Walton A, Anderson KE. Transcriptional, translational, and physiological signatures of undernourished honey bees (Apis mellifera) suggest a role for hormonal factors in hypopharyngeal gland degradation. Journal of Insect Physiology, 2016, 85: 65-75. DOI:10.1016/j.jinsphys.2015.11.016 |

| [51] | Jack CJ, Uppala SS, Lucas HM, Sagili RR. Effects of pollen dilution on infection of Nosema ceranae in honey bees. Journal of Insect Physiology, 2016, 87: 12-19. DOI:10.1016/j.jinsphys.2016.01.004 |

| [52] | Vidau C, Panek J, Texier C, Biron DG, Belzunces LP, Le Gall M, Broussard C, Delbac F, El Alaoui H. Differential proteomic analysis of midguts from Nosema ceranae-infected honeybees reveals manipulation of key host functions. Journal of Invertebrate Pathology, 2014, 121: 89-96. DOI:10.1016/j.jip.2014.07.002 |

| [53] | Kurze C, Dosselli R, Grassl J, Le Conte Y, Kryger P, Baer B, Moritz RFA. Differential proteomics reveals novel insights into Nosema-honey bee interactions. Insect Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 2016, 79: 42-49. DOI:10.1016/j.ibmb.2016.10.005 |

| [54] | Wang DR, Mofller FE. The division of labor and queen attendance behavior of Nosema-infected worker honey bees. Journal of Economic Entomology, 1970, 63(5): 1539-1541. DOI:10.1093/jee/63.5.1539 |

| [55] | Dussaubat C, Maisonnasse A, Crauser D, Beslay D, Costagliola G, Soubeyrand S, Kretzchmar A, Le Conte Y. Flight behavior and pheromone changes associated to Nosema ceranae infection of honey bee workers (Apis mellifera) in field conditions. Journal of Invertebrate Pathology, 2013, 113(1): 42-51. DOI:10.1016/j.jip.2013.01.002 |

| [56] | Higes M, Martín-Hernández R, García-Palencia P, Marín P, Meana A. Horizontal transmission of Nosema ceranae (Microsporidia) from worker honeybees to Queens (Apis mellifera). Environmental Microbiology Reports, 2009, 1(6): 495-498. DOI:10.1111/j.1758-2229.2009.00052.x |

| [57] | Barron AB. Death of the bee hive: understanding the failure of an insect society. Current Opinion in Insect Science, 2015, 10: 45-50. DOI:10.1016/j.cois.2015.04.004 |

| [58] | Perry CJ, S?vik E, Myerscough MR, Barron AB. Rapid behavioral maturation accelerates failure of stressed honey bee colonies. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2015, 112(11): 3427-3432. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1422089112 |

| [59] | Higes M, García-Palencia P, Urbieta A, Nanetti A, Martín-Hernández R. Nosema apis and Nosema ceranae tissue tropism in worker honey bees (Apis mellifera). Veterinary Pathology, 2020, 57(1): 132-138. DOI:10.1177/0300985819864302 |

| [60] | Aronstein KA, Webster TC, Saldivar E. A serological method for detection of Nosema ceranae. Journal of Applied Microbiology, 2013, 114(3): 621-625. DOI:10.1111/jam.12066 |

| [61] | Cornman RS, Chen YP, Schatz MC, Street C, Zhao Y, Desany B, Egholm M, Hutchison S, Pettis JS, Lipkin WI, Evans JD. Genomic analyses of the microsporidian Nosema ceranae, an emergent pathogen of honey bees. PLoS Pathogens, 2009, 5(6): e1000466. DOI:10.1371/journal.ppat.1000466 |

| [62] | Tlak Gajger I, Vugrek O, Grilec D, Petrinec Z. Prevalence and distribution of Nosema ceranae in Croatian honeybee colonies. Veterinární Medicína, 2010, 55(9): 457-462. |

| [63] | Van Den Heever JP, Thompson TS, Curtis JM, Ibrahim A, Pernal SF. Fumagillin: an overview of recent scientific advances and their significance for apiculture. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2014, 62(13): 2728-2737. DOI:10.1021/jf4055374 |

| [64] | Williams GR, Sampson MA, Shutler D, Rogers REL. Does fumagillin control the recently detected invasive parasite Nosema ceranae in western honey bees (Apis mellifera)?. Journal of Invertebrate Pathology, 2008, 99(3): 342-344. DOI:10.1016/j.jip.2008.04.005 |

| [65] | Higes M, Nozal MJ, Alvaro A, Barrios L, Meana A, Martín-Hernández R, Bernal JL, Bernal J. The stability and effectiveness of fumagillin in controlling Nosema ceranae (Microsporidia) infection in honey bees (Apis mellifera) under laboratory and field conditions. Apidologie, 2011, 42(3): 364-377. DOI:10.1007/s13592-011-0003-2 |

| [66] | Huang WF, Solter LF, Yau PM, Imai BS. Nosema ceranae escapes fumagillin control in honey bees. PLoS Pathogens, 2013, 9(3): e1003185. DOI:10.1371/journal.ppat.1003185 |

| [67] | Xie ZY, Lin JH, Tan J, Shu KX. The history and advances of DNA sequencing technology. Biotechnology Bulletin, 2010(8): 64-70. (in Chinese) 解增言, 林俊华, 谭军, 舒坤贤. DNA测序技术的发展历史与最新进展. 生物技术通报, 2010(8): 64-70. |

| [68] | Schwarz RS, Huang Q, Evans JD. Hologenome theory and the honey bee pathosphere. Current Opinion in Insect Science, 2015, 10: 1-7. DOI:10.1016/j.cois.2015.04.006 |

| [69] | Moran NA. Genomics of the honey bee microbiome. Current Opinion in Insect Science, 2015, 10: 22-28. DOI:10.1016/j.cois.2015.04.003 |

| [70] | Kwong WK, Moran NA. Gut microbial communities of social bees. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 2016, 14(6): 374-384. DOI:10.1038/nrmicro.2016.43 |

| [71] | Li JH, Evans JD, Li WF, Zhao YZ, Degrandi-Hoffman G, Huang SK, Li ZG, Hamilton M, Chen YP. New evidence showing that the destruction of gut bacteria by antibiotic treatment could increase the honey bee's vulnerability to Nosema infection. PLoS ONE, 2017, 12(11): e0187505. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0187505 |

| [72] | Raymann K, Shaffer Z, Moran NA. Antibiotic exposure perturbs the gut microbiota and elevates mortality in honeybees. PLoS Biology, 2017, 15(3): e2001861. DOI:10.1371/journal.pbio.2001861 |

| [73] | Engel P, Bartlett KD, Moran NA. The bacterium Frischella perrara causes scab formation in the gut of its honeybee host. mBio, 2015, 6(3): e00193-e00115. |

| [74] | Arredondo D, Castelli L, Porrini MP, Garrido PM, Eguaras MJ, Zunino P, Antúnez K. Lactobacillus kunkeei strains decreased the infection by honey bee pathogens Paenibacillus larvae and Nosema ceranae. Beneficial Microbes, 2018, 9(2): 279-290. DOI:10.3920/BM2017.0075 |

| [75] | Szyma? B, ?angowska A, Kazimierczak-Baryczko M. Histological structure of the midgut of honey bees (Apis mellifera L.) fed pollen substitutes fortified with probiotics.. Journal of Apicultural Science, 2012, 56(1): 5-12. DOI:10.2478/v10289-012-0001-2 |

| [76] | Rubanov A, Russell KA, Rothman JA, Nieh JC, McFrederick QS. Intensity of Nosema ceranae infection is associated with specific honey bee gut bacteria and weakly associated with gut microbiome structure. Scientific Reports, 2019, 9: 3820. DOI:10.1038/s41598-019-40347-6 |

| [77] | Kwong WK, Engel P, Koch H, Moran NA. Genomics and host specialization of honey bee and bumble bee gut symbionts. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2014, 111(31): 11509-11514. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1405838111 |

| [78] | Engel P, Stepanauskas R, Moran NA. Hidden diversity in honey bee gut symbionts detected by single-cell genomics. PLoS Genetics, 2014, 10(9): e1004596. DOI:10.1371/journal.pgen.1004596 |

| [79] | Baffoni L, Gaggìa F, Alberoni D, Cabbri R, Nanetti A, Biavati B, Di Gioia D. Effect of dietary supplementation of Bifidobacterium and Lactobacillus strains in Apis mellifera L.against Nosema ceranae. Beneficial Microbes, 2016, 7(1): 45-51. DOI:10.3920/BM2015.0085 |

| [80] | Ptaszyńska AA, Borsuk G, Zdybicka-Barabas A, Cytryńska M, Ma?ek W. Are commercial probiotics and prebiotics effective in the treatment and prevention of honeybee nosemosis C?. Parasitology Research, 2016, 115(1): 397-406. DOI:10.1007/s00436-015-4761-z |

| [81] | Bravo J, Carbonell V, Sepúlveda B, Delporte C, Valdovinos CE, Martín-Hernández R, Higes M. Antifungal activity of the essential oil obtained from Cryptocarya alba against infection in honey bees by Nosema ceranae. Journal of Invertebrate Pathology, 2017, 149: 141-147. DOI:10.1016/j.jip.2017.08.012 |

| [82] | Arismendi N, Vargas M, López MD, Barría Y, Zapata N. Promising antimicrobial activity against the honey bee parasite Nosema ceranae by methanolic extracts from Chilean native plants and Propolis. Journal of Apicultural Research, 2018, 57(4): 522-535. DOI:10.1080/00218839.2018.1453006 |

| [83] | Porrini MP, Fernández NJ, Garrido PM, Gende LB, Medici SK, Eguaras MJ. In vivo evaluation of antiparasitic activity of plant extracts on Nosema ceranae (Microsporidia). Apidologie, 2011, 42(6): 700-707. DOI:10.1007/s13592-011-0076-y |

| [84] | Yemor T, Phiancharoen M, Eric Benbow M, Suwannapong G. Effects of stingless bee Propolis on Nosema ceranae infected Asian honey bees, Apis cerana. Journal of Apicultural Research, 2015, 54(5): 468-473. DOI:10.1080/00218839.2016.1162447 |

| [85] | Suwannapong G, Maksong S, Phainchajoen M, Benbow ME, Mayack C. Survival and health improvement of Nosema infected Apis florea (Hymenoptera: Apidae) bees after treatment with Propolis extract. Journal of Asia-Pacific Entomology, 2018, 21(2): 437-444. DOI:10.1016/j.aspen.2018.02.006 |

| [86] | Przyby?ek I, Karpiński TM. Antibacterial properties of Propolis. Molecules, 2019, 24(11): 2047. DOI:10.3390/molecules24112047 |

| [87] | Corrêa JL, Veiga FF, Jarros IC, Costa MI, Castilho PF, de Oliveira KMP, Rosseto HC, Bruschi ML, Svidzinski TIE, Negri M. Propolis extract has bioactivity on the wall and cell membrane of Candida albicans. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 2020, 256: 112791. DOI:10.1016/j.jep.2020.112791 |

| [88] | Mahmoodzadeh Hosseini H, Hamzeh Pour S, Amani J, Jabbarzadeh S, Hosseinabadi M, Mirhosseini SA. The effect of Propolis on inhibition of Aspergillus parasiticus growth, aflatoxin production and expression of aflatoxin biosynthesis pathway genes. Journal of Environmental Health Science and Engineering, 2020, 18(1): 297-302. DOI:10.1007/s40201-020-00467-y |

| [89] | Mura A, Pusceddu M, Theodorou P, Angioni A, Floris I, Paxton RJ, Satta A. Propolis consumption reduces Nosema ceranae infection of European honey bees (Apis mellifera). Insects, 2020, 11(2): 124. DOI:10.3390/insects11020124 |

| [90] | Borges D, Guzman-Novoa E, Goodwin PH. Control of the microsporidian parasite Nosema ceranae in honey bees (Apis mellifera) using nutraceutical and immuno-stimulatory compounds. PLoS ONE, 2020, 15(1): e0227484. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0227484 |

| [91] | Burnham AJ. Scientific advances in controlling Nosema ceranae (Microsporidia) infections in honey bees (Apis mellifera). Frontiers in Veterinary Science, 2019, 6: 79. DOI:10.3389/fvets.2019.00079 |

| [92] | Fire A, Xu SQ, Montgomery MK, Kostas SA, Driver SE, Mello CC. Potent and specific genetic interference by double-stranded RNA in Caenorhabditis elegans. Nature, 1998, 391(6669): 806-811. DOI:10.1038/35888 |

| [93] | Yu N, Christiaens O, Liu JS, Niu JZ, Cappelle K, Caccia S, Huvenne H, Smagghe G. Delivery of dsRNA for RNAi in insects: an overview and future directions. Insect Science, 2013, 20(1): 4-14. DOI:10.1111/j.1744-7917.2012.01534.x |

| [94] | Zhang J, Khan SA, Heckel DG, Bock R. Next-generation insect-resistant plants: RNAi-mediated crop protection. Trends in Biotechnology, 2017, 35(9): 871-882. DOI:10.1016/j.tibtech.2017.04.009 |

| [95] | Gundersen DE, Adrianos SL, Allen ML, Becnel JJ., Chen Y, Choi MY, Estep A, Evans JD, Garczynski SF, Geib SM, Ghosh SB, Handler AM, Hasegawa DK, Heerman MC, Hull JJ, Hunter WB, Kaur N, Li J, Li W, Ling K, Nayduch D, Oppert BS, Perera OP, Perkin LC, Sanscrainte ND, Sim SB, Sparks M, Temeyer KB, Vander Meer RK, Wintermantel WM, James RR, Hackett KJ, Coates BS.. Arthropod genomics research in the United States Department of Agriculture-Agricultural Research Service: applications of RNA interference and CRISPR gene editing technologies in pest control.. Trends in Entomology, 2017, 13: 109-137. |

| [96] | Cornman RS, Chen YP, Schatz MC, Street C, Zhao Y, Desany B, Egholm M, Hutchison S, Pettis JS, Lipkin WI, Evans JD. Genomic analyses of the microsporidian Nosema ceranae, an emergent pathogen of honey bees. PLoS Pathogens, 2009, 5(6): e1000466. DOI:10.1371/journal.ppat.1000466 |

| [97] | Paldi N, Glick E, Oliva M, Zilberberg Y, Aubin L, Pettis J, Chen YP, Evans JD. Effective gene silencing in a microsporidian parasite associated with honeybee (Apis mellifera) colony declines. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2010, 76(17): 5960-5964. DOI:10.1128/AEM.01067-10 |

| [98] | Li WF, Evans JD, Huang Q, Rodríguez-García C, Liu J, Hamilton M, Grozinger CM, Webster TC, Su SK, Chen YP. Silencing the honey bee (Apis mellifera) naked cuticle gene (nkd) improves host immune function and reduces Nosema ceranae infections. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2016, 82(22): 6779-6787. DOI:10.1128/AEM.02105-16 |

| [99] | Rodríguez-García C, Evans JD, Li WF, Branchiccela B, Li JH, Heerman MC, Banmeke O, Zhao YZ, Hamilton M, Higes M, Martín-Hernández R, Chen YP. Nosemosis control in European honey bees Apis mellifera by silencing the gene encoding Nosema ceranae polar tube protein 3. Journal of Experimental Biology, 2018, 221(19): jeb184606. |

| [100] | Huang Q, Li W, Chen Y, Retschnig-Tanner G, Yanez O, Neumann P, Evans JD. Dicer regulates Nosema ceranae proliferation in honeybees. Insect Molecular Biology, 2019, 28(1): 74-85. DOI:10.1111/imb.12534 |

| [101] | Gordon MD, Dionne MS, Schneider DS, Nusse R. WntD is a feedback inhibitor of Dorsal/NF-κB in Drosophila development and immunity. Nature, 2005, 437(7059): 746-749. DOI:10.1038/nature04073 |

| [102] | Zeng W, Wharton KA, Mack JA, Wang K, Gadbaw M, Suyama K, Klein PS, Scott MP. Naked cuticle encodes an inducible antagonist of Wnt signalling. Nature, 2000, 403(6771): 789-795. DOI:10.1038/35001615 |

| [103] | Li WF, Evans JD, Huang Q, Rodríguez-García C, Liu J, Hamilton M, Grozinger CM, Webster TC, Su SK, Chen YP. Silencing the honey bee (Apis mellifera) naked cuticle gene (nkd) improves host immune function and reduces Nosema ceranae infections. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2016, 82(22): 6779-6787. DOI:10.1128/AEM.02105-16 |

| [104] | Huang Q, Lattorff HMG, Kryger P, Le Conte Y, Moritz RFA. A selective sweep in a microsporidian parasite Nosema-tolerant honeybee population, Apis mellifera. Animal Genetics, 2014, 45(2): 267-273. DOI:10.1111/age.12114 |

| [105] | Bourgeois AL, Rinderer TE, Sylvester HA, Holloway B, Oldroyd BP. Patterns of Apis mellifera infestation by Nosema ceranae support the parasite hypothesis for the evolution of extreme polyandry in eusocial insects. Apidologie, 2012, 43(5): 539-548. DOI:10.1007/s13592-012-0121-5 |

| [106] | Mendoza Y, Antúnez K, Branchiccela B, Anido M, Santos E, Invernizzi C. Nosema ceranae and RNA viruses in European and Africanized honeybee colonies (Apis mellifera) in Uruguay. Apidologie, 2014, 45(2): 224-234. DOI:10.1007/s13592-013-0241-6 |

| [107] | Zhang JY, Diao QY, Dai PL, Chu YN, Wu YY, Zhou T, Wang Q. Germplasm distribution of Nosema spp. in Apis mellifera in China.. Chinese Journal of Animal and Veterinary Sciences, 2015, 46(9): 1638-1643. (in Chinese) 张建燕, 刁青云, 代平礼, 褚艳娜, 吴艳艳, 周婷, 王强. 中国部分主要养蜂区侵染西方蜜蜂(Apis mellifera)群微孢子虫种质分布调查. 畜牧兽医学报, 2015, 46(9): 1638-1643. |

| [108] | Graystock P, Yates K, Darvill B, Goulson D, Hughes WOH. Emerging dangers: Deadly effects of an emergent parasite in a new pollinator host. Journal of Invertebrate Pathology, 2013, 114(2): 114-119. DOI:10.1016/j.jip.2013.06.005 |

| [109] | Fürst MA, McMahon DP, Osborne JL, Paxton RJ, Brown MJF. Disease associations between honeybees and bumblebees as a threat to wild pollinators. Nature, 2014, 506(7488): 364-366. DOI:10.1038/nature12977 |

| [110] | Arbulo N, Antúnez K, Salvarrey S, Santos E, Branchiccela B, Martín-Hernández R, Higes M, Invernizzi C. High prevalence and infection levels of Nosema ceranae in bumblebees Bombus atratus and Bombus bellicosus from Uruguay. Journal of Invertebrate Pathology, 2015, 130: 165-168. DOI:10.1016/j.jip.2015.07.018 |

| [111] | Fayer R, Santin-Duran M. Epidemiology of microsporidia in human infections. Microsporidia.. Chichester, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2014: 135-164. |