彭涛, 张斯仪, 王璐婷, 何祯珍, 舒龙飞

中山大学环境科学与工程学院, 南方海洋科学与工程广东省实验室(珠海), 环境微生物组学研究中心, 广东 广州 510006

收稿日期:2019-10-03;修回日期:2019-11-27;网络出版日期:2019-12-05

基金项目:国家自然科学基金(31970384,41907024)

*通信作者:舒龙飞。E-mail:shulf@mail.sysu.edu.cn.

摘要:阿米巴是原生动物的主要类群,是陆地和水生生态系统的关键组成部分。阿米巴与细菌之间有着密切而复杂的相互作用。一方面,阿米巴通过捕食直接影响细菌群落与多样性,增强细菌活性。另一方面,细菌也进化出抵抗捕食的机制来抵抗甚至感染阿米巴,反向影响阿米巴的生长和多样性。近年来,阿米巴-细菌互作的研究开始受到了广泛关注。本文总结了阿米巴-细菌互作的进化历史、生态关系(捕食、偏利共生、寄生和互利共生)以及其对环境的潜在影响,旨在更好地理解阿米巴-细菌互作这一研究领域,为其他原生动物-微生物之间的研究提供新的思路,也为探究宿主-微生物互作的机制提供参考。

关键词:原生动物阿米巴细菌宿主捕食共生协同进化

Amoebas-bacteria interactions: evolution, ecology and environmental impacts

Tao Peng, Siyi Zhang, Luting Wang, Zhenzhen He, Longfei Shu

Environmental Microbiomics Research Center, Southern Marine Science and Engineering Guangdong Laboratory (Zhuhai), School of Environmental Science and Engineering, Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou 510006, Guangdong Province, China

Received: 3 October 2019; Revised: 27 November 2019; Published online: 5 December 2019

*Corresponding author: Longfei Shu, E-mail:shulf@mail.sysu.edu.cn.

Foundation item: Supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31970384, 41907024)

Abstract: Amoebas are important components of terrestrial ecosystems, and play a key role in soil nutrient cycling and energy flow. Amoebas have complex relationships with bacteria. On one hand, amoebas can directly affect the bacterial community and diversity through predation and enhance bacterial activity. On the other hand, bacteria have also evolved mechanisms to resist predation and even to infect amoebas, thus adversely affecting the growth and diversity of amoebas. In recent years, the interactions between amoebas and bacteria have attracted much attention. This paper summarizes the evolutionary history of amoebas-bacteria interactions, ecological relationships (predation, commensalism, parasitism, and mutualism) and their potential impacts on the environment. This review will improve our understanding about this research field and provide new ideas for the study of other protists-bacteria interactions, as well as exploring the mechanism of host-bacteria interactions in general.

Keywords: protistamoebabacteriahostpreysymbiosiscoevolution

阿米巴(amoebas)是一类可通过伸长或收回伪足来改变自身形状的单细胞真核原生生物。阿米巴也被称作变形虫、阿米巴原虫,为了统一,本综述将使用阿米巴作为标准的名称。阿米巴是动物与真菌的姐妹群,源自它们共同的祖先单鞭毛生物。目前自然环境中已发现2400多种阿米巴,它们的细胞大小差异非常大:最小的多聚覆毛虫(Massisteria voersi)大小仅有2.3–3.0 μm,而沼泽多核变形虫(Pelomyxa palustris)最大能达到5000 μm。阿米巴在环境中分布极其广泛,常见于生物膜、水-土壤、水-动物、水-植物和水-空气界面上[1]。它们主要以细菌、藻类、真菌和小有机颗粒为食,通过吞噬作用摄取食物[1-2]。

近年来,阿米巴与细菌之间的互作已逐渐成为国内外研究的热点。阿米巴能和环境中大量的细菌形成复杂的互作关系[3-6]:它们捕食细菌,也会被致病菌感染,还能和细菌形成稳定的共生关系[7-9]。因此,阿米巴在陆地和水生生态系统中对微生物群落调控扮演重要角色。此外,许多阿米巴被发现携带细菌,包括大量的致病菌,这使其成为了病原体的环境宿主和载体[5, 10]。因此,研究阿米巴-细菌互作也对公共卫生及人类健康十分关键。

本文将总结阿米巴-细菌互作的进化历史、生态关系(捕食、偏利共生、寄生和互利共生)以及其对环境的潜在影响,为原生动物-微生物之间的研究提供新的思路,并进一步探究宿主-微生物互作的生态进化机理。

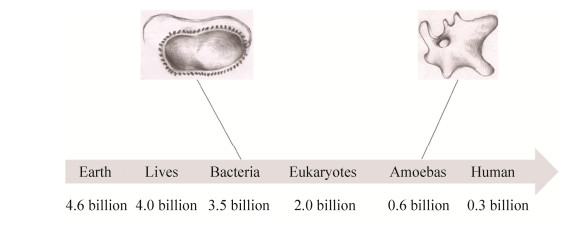

1 阿米巴-细菌互作的进化史 细菌(最早的原核生物出现于约35亿年前)和阿米巴(最早的真核生物出现于约18.5亿年前)是最早出现在地球上的生命之一(图 1)。因此,早在细菌感染动物、植物和人之前,它们和阿米巴之间已经有了非常悠久的互作历史。阿米巴进化出了一系列的机制来追踪、捕食、吞噬、杀死和消化细菌[11-14]。与此同时,细菌也进化出了相应的对策来应对阿米巴的捕食,反过来感染阿米巴,甚至形成稳定的共生关系[7-9, 15-16]。

|

| 图 1 阿米巴-细菌互作的进化时间线[29-30] Figure 1 Evolutionary timeline of amoeba and bacteria[29-30]. |

| 图选项 |

阿米巴-细菌长期的互作历史,使其成为一个优良的研究宿主-细菌互作的模式系统。阿米巴-细菌互作几乎涵盖了宿主-细菌互作的所有方面,包括寄生、偏利共生、互利共生等[9]。阿米巴作为模式物种已被广泛应用于细胞生物学、医学、社会进化学以及生态学等领域[17-21]。同时,因为其具有:(1)宿主阿米巴和细菌都可在实验室内纯培养,操作方便;(2)可将阿米巴和细菌分离,并重新进行组合(其他系统几乎不能做到);(3)可分别和同时对阿米巴细菌进行分子、细胞和进化上的操作等优点,阿米巴-细菌互作为我们提供了一个研究宿主和细菌互作关系的优良模型,也可以为其他宿主-细菌互作系统提供参考。

阿米巴-细菌漫长的互作历史,也使其对公共卫生及人类健康产生重大影响。阿米巴可以携带大量的致病菌,使其成为病原体的环境载体和宿主[8-10, 22-24]。同时,因为阿米巴和动物免疫细胞在进化上具有同源性,它们在细胞结构、免疫机制和功能基因上都存在相似性,这意味着能感染阿米巴的致病菌,往往也能感染包括人在内的动物免疫细胞,危害人类健康[25-28]。

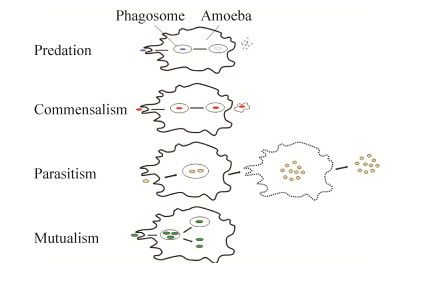

2 阿米巴-细菌互作的生态关系 阿米巴-细菌之间的互作类型包括捕食、偏利共生、寄生以及互利共生等四种生态关系(图 2,表 1),以下我们对其分别进行介绍。

|

| 图 2 阿米巴-细菌的互作关系 Figure 2 Diagram of amoeba-bacteria interactions. |

| 图选项 |

表 1. 阿米巴-细菌互作的生态关系 Table 1. Relationships between amoebas and bacteria

| Types | Amoebas | Bacteria | References |

| Predation | Acanthamoeba | Pneumococci | [14] |

| D. discoideum | Klebsiella pneumoniae | [14] | |

| Acanthamoeba | Betaproteobacteria | [35] | |

| Commensalism | Acanthamoeba | Amoebophilus asiaticus | [37] |

| Acanthamoeba | Caedibacter acanthamoebae | [38] | |

| Parasitism | Various amoebas | Legionella pneumophila | [39-41] |

| D. discoideum | Mycobacterium marinum | [40, 42] | |

| D. discoideum | Mycobacterium tuberculosis | [40, 42] | |

| D. discoideum | Neisseria meningitides | [43] | |

| Acanthamoeba | Burkholderia cenocepacia | [44-45] | |

| D. discoideum | Pseudomonas aeruginosa | [46] | |

| Acanthamoeba | Chlamydophila pneumoniae | [47] | |

| Mutualism | D. discoideum | Burkholderia agricolaris | [7-8, 16, 48] |

| D. discoideum | Burkholderia hayleyella | [7-8, 16, 48] | |

| D. discoideum | Burkholderia bonniea | [8, 22] |

表选项

2.1 捕食 在陆地和水生生态系统中,细菌是阿米巴的主要食物。阿米巴进化出了一系列的机制来追踪、捕食、吞噬、杀死和消化细菌[11-14]。首先,阿米巴能够通过趋化作用(细胞沿浓度梯度向着化学刺激物作定向移动)在一定距离内发现并追逐细菌[31]。随后,利用吞噬作用(将周围环境中的固体颗粒例如细菌等通过小泡的形式吞食进入细胞内部)吞噬细菌。通过吞噬作用产生的吞噬体会与包含多种消化酶的溶酶体融合形成吞噬溶酶体,细菌会被消化成营养物质输送到细胞质中[12, 32-33]。因此,作为非常有效率的细菌捕食者,阿米巴能够显著地调节和改变微生物群落[34-35]。

但是到目前为止,阿米巴对细菌的选择性摄食机制仍是一个有待阐明的问题。即,阿米巴是否会选择性地摄食特定类群的细菌?这不仅关系到阿米巴对细菌的选择性群落调控,也关系到其生态功能。美国贝勒医学院的Kuspa实验室研究了模式阿米巴盘基网柄菌(Dictyostelium discoideum)捕食革兰氏阴性菌和阳性菌时的转录组差异,他们发现盘基网柄菌捕食两类细菌时有着明显的基因表达差异[36]。他们还发现有一些基因例如gp130、AlyL等只在捕食革兰氏阳性菌时需要[36]。美国休斯敦大学的Ostrowski同样利用趋化实验发现,盘基网柄菌更倾向于向革兰氏阴性菌移动[11]。这些研究表明,阿米巴似乎更倾向于捕食革兰氏阴性菌。但是需要指出的是,以上研究都是利用模式阿米巴盘基网柄菌作为研究对象,且实验都是在平板上进行。未来的研究应该采用更多的阿米巴物种,在土壤等真实环境中模拟其摄食行为。

2.2 偏利共生 在漫长的互作历史中,有一些细菌进化出了对阿米巴捕食的抗性,这些细菌被称作阿米巴抗性细菌(Amoeba-resisting bacteria,ARB)[10, 49]。在这里,我们定义这种能够抵抗阿米巴捕食,但同时又不对阿米巴的适合度造成显著影响的关系称为偏利共生(图 2)。这些细菌不仅能躲避阿米巴的捕食,还可以躲藏在阿米巴内部从而获得保护,并将其作为环境传播的载体和宿主[10, 49-50]。在阿米巴中,抗性细菌可以在不利的环境下暂时或持久生存,尤其是当宿主阿米巴形成非常抗逆的孢子或者包囊时,保护其免受外界不利条件的损害[24]。

目前已经报道的抗性细菌逃避阿米巴捕食的策略主要有三种[9]:一是从吞噬体中逃离到细胞质中,相对来说细胞质是有利于细菌生长的温和环境,它能提供大量的营养物质并且让细菌免于受到宿主免疫系统的杀死[51]。第二种是改变吞噬体的微环境:一些细菌能够阻碍吞噬体-溶酶体融合,延迟吞噬体酸化从而避免吞噬溶酶体对其的杀伤[52]。第三种是适应吞噬体的微环境,这些细菌适应了低pH等胁迫的吞噬体环境从而可以存活其中[9]。在躲避过不利条件以后,这些偏利共生的细菌会被包裹在源自阿米巴的多层膜结构中,被重新释放到环境中[53]。

2.3 寄生 在众多的阿米巴抗性细菌中,有一些细菌进化出了感染甚至杀死阿米巴宿主的能力,这些细菌我们称之为阿米巴致病菌[9]。因为阿米巴细胞和动物免疫细胞在进化上高度同源,这些阿米巴致病菌往往也是动物甚至是人的致病菌,容易感染引发疾病从而影响人体健康,例如分支杆菌属、嗜肺军团菌属和其他病原体等[10, 49-54]。

嗜肺军团菌属是目前研究最多的阿米巴致病菌之一[55-57]。嗜肺军团菌是一种兼性胞内寄生菌,它广泛存在于水体和土壤中,能够入侵人类肺泡巨噬细胞和阿米巴并寄生。嗜肺军团菌能够导致军团病,其作为军团病重症肺炎的致病因子已被证实,通常是人体吸入由空调装置或淋浴等水系统产生的污染气溶胶而引起的[58]。嗜肺军团菌可以入侵阿米巴并利用其作为复制和传播的环境载体[59]。在阿米巴体内,它能破坏小泡传输,产生嗜肺军团小泡(Legionella containing vacuole,LCV),阻止吞噬体-溶酶体融合从而在细胞内复制,最后完成胞内复制的细菌从宿主细胞中逸出导致宿主细胞死亡[60-64]。

阐明宿主与致病菌的关系是生命科学和医学的核心问题。由于阿米巴具有易培养、方便用于药物测试、有成熟的分子和细胞生物技术等优势,是一个潜在的研究宿主-致病菌互作的优良模型[65]。这将有助于新兴病原体研究领域的发展,有利于进一步剖析致病菌对人类健康的影响,在未来宿主-致病菌研究上具有重要的参考价值。

2.4 互利共生 细菌与真核生物的长期互作会导致长期稳定的互利共生关系的形成[66-67]。经典的案例包括鱿鱼-弧菌共生[68]、蚜虫内生菌共生以及根瘤菌与豆科植物之间的共生固氮关系[69-70]。阿米巴和细菌之间有着漫长的互作历史,它们之间亦存在生物学意义上的合作的关系。其中,最著名的例子是社会性阿米巴盘基网柄菌与其共生菌之间的合作[8, 16, 48]。

盘基网柄菌是一种社会性阿米巴,正常状态下它们以细菌为食物,在食物耗尽的情况下,成千上万的阿米巴会聚集在一起并形成多细胞的蛞蝓体进行迁移,当迁移到新的地点以后会最终形成子实体和位于其顶部的孢子。2011年的一项研究发现,一些从野外收集的盘基网柄菌克隆会在其整个生活史中携带细菌,当转移到新的食物营养匮乏的环境中时,这些细菌能够作为它们的食物来源,这些能携带、播种细菌的盘基网柄菌克隆称为阿米巴农民(Farmer)[16]。后续的研究表明,这种携带并播种细菌的性状是由一种名为伯克氏菌的共生菌诱导的[48]。伯克氏菌属(Burkholderia)属于β-变形菌,广泛分布于环境中,它们在土壤中含量丰富同时与许多真菌、植物和无脊椎动物形成共生关系[71-73]。在它们的共生关系中,盘基网柄菌为伯克氏菌的生长和传播提供载体,而伯克氏菌为盘基网柄菌的生长、抵抗毒素和种内竞争提供优势[8, 16, 48, 74-76]。

社会性阿米巴-伯克氏菌互作是一种相对简单且可控的研究共生与协同进化的新模式系统,也是作者实验室研究的主要方向[7-9]。通过阐明其互作机制,将有利于回答宿主-细菌共生领域亟待解决的科学问题,以及帮助了解不同共生菌对动物、植物以及人类本身的健康的影响。

3 阿米巴-细菌互作的环境影响 土壤原生动物作为土壤生态系统的重要组成部分,既参与了微生物所介导的物质循环和能量流动,同时参与了对微生物的捕食作用,因此在土壤生态系统中发挥关键作用[77]。阿米巴-细菌在促进土壤生态系统的物质循环和能量流动以及提高微生物、植物和动物活力方面起着不可或缺的作用,对于提高生物群落的稳定性和生产力同样非常关键。它们的主要生态功能包括:(1)调控细菌群落。阿米巴通常参与食物网中细菌的捕食,是土壤中细菌的主要捕食者,最终调控细菌群落、增加细菌活性[35, 78];(2)刺激土壤养分转化和碳氮磷等元素矿化[79];(3)促进植物的生长[78, 80]。一方面,阿米巴对细菌的捕食提高了微生物的产量和营养物的矿化,间接促进了植物的生长;同时,阿米巴捕食细菌生物量中的N以NH4+的形式释放被植物根系吸收,进而促进植物生长。

阿米巴同样广泛地分布在水环境中。已有报道从水生阿米巴中分离出了大量的阿米巴抗性细菌,其中包括大量水传播微生物病原体,如嗜肺军团菌(L. pneumophila)、霍乱弧菌(Vibriocholerae)、绿脓假单胞菌(Pseudomonas aeruginosa)、幽门螺杆菌(Helicobacter pylori)、鸟分枝杆菌(Mycobacterium avium)等[23, 81]。阿米巴成为了这些细菌病原体传播的环境载体,使其能够耐受恶劣的环境胁迫并在环境中传播增殖。因此,阐明阿米巴与阿米巴抗性细菌之间的互作,对公共卫生与健康有着重大影响。

包括阿米巴在内的原生动物在污水处理中同样发挥着显著作用。它们能促进细菌活力,提高出水品质,对水质的净化起了积极的作用。它们的主要作用方式包括:(1)直接净化作用:通过体表渗透吸收水中的可溶性有机质,捕食水体中的颗粒物,不仅能够降低水体中有机营养物的负荷,而且增加了水体的透明度同时减弱水中病原菌的毒害作用;(2)捕食细菌间接净化作用:由于原生动物捕食细菌的影响,一定程度上能有效刺激细菌迁移,增强了细菌的活性,提高细菌对水体中可溶性物质的摄取能力,从而能够促进水质净化[82],同时吞噬细菌可加快水生生态系统中N、P等元素的矿化,优化基质的碳氮磷比率,促进了污水的进化[83-84];(3)絮凝沉淀作用[85]:原生动物在新陈代谢和自我繁殖过程中,产生的某些代谢物能和水中的特定污染物发生反应使之聚集沉淀进而净化了水质。但是到目前为止,阿米巴在污水处理中的作用的研究相对较少,亟需更多的研究。

4 阿米巴-细菌互作研究的机遇与挑战 早在半个多世纪以前,阿米巴-细菌共生的现象已有报道[86]。但是长期以来,相关的研究主要集中于描述性的研究,利用显微镜或16S rRNA基因测序等技术检测阿米巴共生菌的有无及种类[87-89],而少有涉及到宿主-共生领域亟待解决的科学问题,如宿主-细菌共生系统的起源、形成、维持及协同进化的机制。主要原因在于长期以来,阿米巴-细菌互作研究领域缺乏像大肠杆菌、酵母和小鼠等类似的遗传背景清楚、易于在实验室内进行分子、细胞和进化操作的模式生物。

作者课题组利用一种社会性阿米巴盘基网柄菌及其共生细菌作为研究对象,希望建立一种新的研究共生与协同进化的模式系统。作者课题组此前系统地研究了野外的社会性阿米巴宿主携带细菌的组成、多样性、功能以及协同进化。从来自美国中东部环境的阿米巴样品中,分离了超过两百种可培养的细菌,这表明阿米巴在某种程度成为了“特洛伊木马”,有大量的细菌躲藏在其内部[7-9]。作者的研究发现阿米巴可与细菌选择性互作[7],同时也可与细菌形成稳定的共生关系,而共生时间的长短还会影响它们的协同进化[8]。同时,多个国际顶尖实验室也利用社会性阿米巴AX2和AX4菌株作为模式生物研究宿主-致病菌互作,包括:瑞士日内瓦大学的Thierry Soldati实验室,用社会性阿米巴研究致病菌结核杆菌的致病机理[13, 42, 56];奥地利维也纳大学的Matthias Horn实验室,关注阿米巴与致病菌衣原体的互作[90-91]。

未来,我们希望把社会性阿米巴建立成为一种新的研究共生与协同进化的模式系统。它的遗传背景清晰[20],易于在实验室内进行分子、细胞和进化操作,也是为数不多的可以阐明宿主与其全部共生菌关系和功能的研究系统,将有利于研究宿主-细菌共生系统的起源、形成、维持及协同进化机制等关键科学问题。

5 总结和展望 生物个体携带的共生细菌的组成往往极其的复杂且难以分离,对阐明宿主-共生菌关系的研究造成很大的困难。阿米巴-细菌互作提供了一种相对简单且可控的新的模式系统来研究宿主与共生菌之间的关系,这也是为数不多的可以阐明宿主与其全部共生菌关系和功能的模式系统。然而,目前我们对于阿米巴-细菌互作的功能和机制,以及它们对环境和生态系统功能的理解上仍然面临很多挑战。未来亟待回答的科学问题包括:

(1) 阿米巴-细菌互作的形成和维持机制是什么?

(2) 细菌对阿米巴的生长、健康和适合度有什么影响?

(3) 阿米巴-细菌之间是否存在代谢互补?

(4) 阿米巴-细菌之间是否存在协同进化?具体机制是什么?

(5) 阿米巴-细菌互作对生态系统和环境工程的影响是什么?

References

| [1] | Rodríguez-Zaragoza S. Ecology of free-living amoebae. Critical Reviews in Microbiology, 1994, 20(3): 225-241. |

| [2] | Cosson P, Soldati T. Eat, kill or die:when amoeba meets bacteria. Current Opinion in Microbiology, 2008, 11(3): 271-276. DOI:10.1016/j.mib.2008.05.005 |

| [3] | Steinert M. Pathogen-host interactions in Dictyostelium, Legionella, Mycobacterium and other pathogens. Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology, 2011, 22(1): 70-76. |

| [4] | Richards AM, Von Dwingelo JE, Price CT, Kwaik YA. Cellular microbiology and molecular ecology of Legionella-amoeba interaction. Virulence, 2013, 4(4): 307-314. DOI:10.4161/viru.24290 |

| [5] | Scheid P. Relevance of free-living amoebae as hosts for phylogenetically diverse microorganisms. Parasitology Research, 2014, 113(7): 2407-2414. DOI:10.1007/s00436-014-3932-7 |

| [6] | Khan NA, Siddiqui R. Predator vs aliens:bacteria interactions with Acanthamoeba. Parasitology, 2014, 141(7): 869-874. DOI:10.1017/S003118201300231X |

| [7] | Shu LF, Zhang BJ, Queller DC, Strassmann JE. Burkholderia bacteria use chemotaxis to find social amoeba Dictyostelium discoideum hosts. The ISME Journal, 2018, 12(8): 1977-1993. DOI:10.1038/s41396-018-0147-4 |

| [8] | Shu LF, Brock DA, Geist KS, Miller JW, Queller DC, Strassmann JE, DiSalvo S. Symbiont location, host fitness, and possible coadaptation in a symbiosis between social amoebae and bacteria. eLife, 2018, 7: e42660. DOI:10.7554/eLife.42660 |

| [9] | Strassmann JE, Shu LF. Ancient bacteria-amoeba relationships and pathogenic animal bacteria. PLoS Biology, 2017, 15(5): e2002460. DOI:10.1371/journal.pbio.2002460 |

| [10] | Tosetti N, Croxatto A, Greub G. Amoebae as a tool to isolate new bacterial species, to discover new virulence factors and to study the host-pathogen interactions. Microbial Pathogenesis, 2014, 77: 125-130. DOI:10.1016/j.micpath.2014.07.009 |

| [11] | Rashidi G, Ostrowski EA. Phagocyte chase behaviours:discrimination between gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria by amoebae. Biology Letters, 2019, 15(1): 20180607. DOI:10.1098/rsbl.2018.0607 |

| [12] | Dunn JD, Bosmani C, Barisch C, Raykov L, Lefran?ois LH, Cardenal-Mu?oz E, López-Jiménez AT, Soldati T. Eat prey, live:Dictyostelium discoideum as a model for cell-autonomous defenses. Frontiers in Immunology, 2018, 8: 1906. DOI:10.3389/fimmu.2017.01906 |

| [13] | Zhang XZ, Zhuchenko O, Kuspa A, Soldati T. Social amoebae trap and kill bacteria by casting DNA nets. Nature Communications, 2016, 7(1): 10938. DOI:10.1038/ncomms10938 |

| [14] | Cosson P, Lima WC. Intracellular killing of bacteria:is Dictyostelium a model macrophage or an alien?. Cellular Microbiology, 2014, 16(6): 816-823. DOI:10.1111/cmi.12291 |

| [15] | K?nig L, Wentrup C, Schulz F, Wascher F, Escola S, Swanson MS, Buchrieser C, Horn M. Symbiont-mediated defense against Legionella pneumophila in Amoebae. mBio, 2019, 10(3): e00333-19. DOI:10.1128/mBio.00333-19 |

| [16] | Brock DA, Douglas TE, Queller DC, Strassmann JE. Primitive agriculture in a social amoeba. Nature, 2011, 469(7330): 393-396. DOI:10.1038/nature09668 |

| [17] | Li SI, Purugganan MD. The cooperative amoeba:Dictyostelium as a model for social evolution. Trends in Genetics, 2011, 27(2): 48-54. DOI:10.1016/j.tig.2010.11.003 |

| [18] | Loomis WF. Cell signaling during development of Dictyostelium. Developmental Biology, 2014, 391(1): 1-16. DOI:10.1016/j.ydbio.2014.04.001 |

| [19] | Williams JG. Dictyostelium finds new roles to model. Genetics, 2010, 185(3): 717-726. |

| [20] | Eichinger L, Pachebat JA, Gl?ckner G, Rajandream MA, Sucgang R, Berriman M, Song J, Olsen R, Szafranski K, Xu Q, Tunggal B, Kummerfeld S, Madera M, Konfortov BA, Rivero F, Bankier AT, Lehmann R, Hamlin N, Davies R, Gaudet P, Fey P, Pilcher K, Chen G, Saunders D, Sodergren E, Davis P, Kerhornou A, Nie X, Hall N, Anjard C, Hemphill L, Bason N, Farbrother P, Desany B, Just E, Morio T, Rost R, Churcher C, Cooper J, Haydock S, van Driessche N, Cronin A, Goodhead I, Muzny D, Mourier T, Pain A, Lu M, Harper D, Lindsay R, Hauser H, James K, Quiles M, Madan Babu M, Saito T, Buchrieser C, Wardroper A, Felder M, Thangavelu M, Johnson D, Knights A, Loulseged H, Mungall K, Oliver K, Price C, Quail MA, Urushihara H, Hernandez J, Rabbinowitsch E, Steffen D, Sanders M, Ma J, Kohara Y, Sharp S, Simmonds M, Spiegler S, Tivey A, Sugano S, White B, Walker D, Woodward J, Winckler T, Tanaka Y, Shaulsky G, Schleicher M, Weinstock G, Rosenthal A, Cox EC, Chisholm RL, Gibbs R, Loomis WF, Platzer M, Kay RR, Williams J, Dear PH, Noegel AA, Barrell B, Kuspa A. The genome of the social amoeba Dictyostelium discoideum. Nature, 2005, 435(7038): 43. DOI:10.1038/nature03481 |

| [21] | Katz ER. Dictyostelium:evolution, cell biology, and the development of multicellularity by Richard H Kessin. Quarterly Review of Biology, 2002, 77(4): 453-454. |

| [22] | Haselkorn TS, DiSalvo S, Miller JW, Bashir U, Brock DA, Queller DC, Strassmann JE. The specificity of Burkholderia symbionts in the social amoeba farming symbiosis:prevalence, species, genetic and phenotypic diversity. Molecular Ecology, 2019, 28(4): 847-862. |

| [23] | Balczun C, Scheid PL. Free-living amoebae as hosts for and vectors of intracellular microorganisms with public health significance. Viruses, 2017, 9(4): 65. |

| [24] | Greub G, Raoult D. Microorganisms resistant to free-living amoebae. Clinical Microbiology Reviews, 2004, 17(2): 413-433. DOI:10.1128/CMR.17.2.413-433.2004 |

| [25] | Chamberlain NB, Mehari YT, Hayes BJ, Roden CM, Kidane DT, Swehla AJ, Lorenzana-DeWitt MA, Farone AL, Gunderson JH, Berk SG, Farone MB. Infection and nuclear interaction in mammalian cells by 'Candidatus Berkiella cookevillensis', a novel bacterium isolated from amoebae. BMC Microbiology, 2019, 19(1): 91. |

| [26] | Okubo T, Matsushita M, Nakamura S, Matsuo J, Nagai H, Yamaguchi H. Acanthamoeba S13WT relies on its bacterial endosymbiont to backpack human pathogenic bacteria and resist Legionella infection on solid media. Environmental Microbiology Reports, 2018, 10(3): 344-354. DOI:10.1111/1758-2229.12645 |

| [27] | Taylor-Mulneix DL, Bendor L, Linz B, Rivera I, Ryman VE, Dewan KK, Wagner SM, Wilson EF, Hilburger LJ, Cuff LE, West CM, Harvill ET. Bordetella bronchiseptica exploits the complex life cycle of Dictyostelium discoideum as an amplifying transmission vector. PLoS Biology, 2017, 15(4): e2000420. DOI:10.1371/journal.pbio.2000420 |

| [28] | Valvano MA. Intracellular survival of Burkholderia cepacia complex in phagocytic cells. Canadian Journal of Microbiology, 2015, 61(9): 607-615. DOI:10.1139/cjm-2015-0316 |

| [29] | Glansdorff N, Xu Y, Labedan B. The last universal common ancestor:emergence, constitution and genetic legacy of an elusive forerunner. Biology Direct, 2008, 3(1): 29. |

| [30] | Porter SM, Meisterfeld R, Knoll AH. Vase-shaped microfossils from the Neoproterozoic Chuar Group, Grand Canyon:a classification guided by modern testate amoebae. Journal of Paleontology, 2003, 77(3): 409-429. DOI:10.1666/0022-3360(2003)077<0409:VMFTNC>2.0.CO;2 |

| [31] | Kuburich NA, Adhikari N, Hadwiger JA. Acanthamoeba and Dictyostelium use different foraging strategies. Protist, 2016, 167(6): 511-525. DOI:10.1016/j.protis.2016.08.006 |

| [32] | Lima WC, Balestrino D, Forestier C, Cosson P. Two distinct sensing pathways allow recognition of Klebsiella pneumoniae by Dictyostelium amoebae. Cellular Microbiology, 2014, 16(3): 311-323. DOI:10.1111/cmi.12226 |

| [33] | German N, Doyscher D, Rensing C. Bacterial killing in macrophages and amoeba:do they all use a brass dagger?. Future Microbiology, 2013, 8(10): 1257-1264. DOI:10.2217/fmb.13.100 |

| [34] | Amaro F, Wang W, Gilbert JA, Anderson OR, Shuman HA. Diverse protist grazers select for virulence-related traits in Legionella. The ISME Journal, 2015, 9(7): 1607-1618. DOI:10.1038/ismej.2014.248 |

| [35] | Rosenberg K, Bertaux J, Krome K, Hartmann A, Scheu S, Bonkowski M. Soil amoebae rapidly change bacterial community composition in the rhizosphere of Arabidopsis thaliana. The ISME Journal, 2009, 3(6): 675-684. DOI:10.1038/ismej.2009.11 |

| [36] | Nasser W, Santhanam B, Miranda ER, Parikh A, Juneja K, Rot G, Dinh C, Chen R, Zupan B, Shaulsky G, Kuspa A. Bacterial discrimination by dictyostelid amoebae reveals the complexity of ancient interspecies interactions. Current Biology, 2013, 23(10): 862-872. DOI:10.1016/j.cub.2013.04.034 |

| [37] | Horn M, Harzenetter MD, Linner T, Schmid EN, Müller KD, Michel R, Wagner M. Members of the Cytophaga-Flavobacterium-Bacteroides phylum as intracellular bacteria of acanthamoebae:proposal of 'Candidatus Amoebophilus asiaticus'. Environmental Microbiology, 2001, 3(7): 440-449. DOI:10.1046/j.1462-2920.2001.00210.x |

| [38] | Horn M, Fritsche TR, Gautom RK, Schleifer KH, Wagner M. Novel bacterial endosymbionts of Acanthamoeba spp. related to the Paramecium caudatum symbiont Caedibacter caryophilus. Environmental Microbiology, 1999, 1(4): 357-367. DOI:10.1046/j.1462-2920.1999.00045.x |

| [39] | Shin S, Roy CR. Host cell processes that influence the intracellular survival of Legionella pneumophila. Cellular Microbiology, 2008, 10(6): 1209-1220. DOI:10.1111/j.1462-5822.2008.01145.x |

| [40] | Clarke M. Recent insights into host-pathogen interactions from Dictyostelium. Cellular Microbiology, 2010, 12(3): 283-291. DOI:10.1111/j.1462-5822.2009.01413.x |

| [41] | Franco IS, Shuman HA, Charpentier X. The perplexing functions and surprising origins of Legionella pneumophila type Ⅳ secretion effectors. Cellular Microbiology, 2009, 11(10): 1435-1443. DOI:10.1111/j.1462-5822.2009.01351.x |

| [42] | Hagedorn M, Rohde KH, Russell DG, Soldati T. Infection by tubercular mycobacteria is spread by nonlytic ejection from their amoeba hosts. Science, 2009, 323(5922): 1729-1733. DOI:10.1126/science.1169381 |

| [43] | Colucci AM, Peracino B, Tala A, Bozzaro S, Alifano P, Bucci C. Dictyostelium discoideum as a model host for meningococcal pathogenesis. Medical Science Monitor, 2008, 14(7): BR134-40. |

| [44] | Marolda CL, Haur?der B, John MA, Michel R, Valvano MA. Intracellular survival and saprophytic growth of isolates from the Burkholderia cepacia complex in free-living amoebae. Microbiology, 1999, 145(7): 1509-1517. DOI:10.1099/13500872-145-7-1509 |

| [45] | Aubert DF, Flannagan RS, Valvano MA. A novel sensor kinase-response regulator hybrid controls biofilm formation and type Ⅵ secretion system activity in Burkholderia cenocepacia. Infection and Immunity, 2008, 76(5): 1979-1991. DOI:10.1128/IAI.01338-07 |

| [46] | Carilla-Latorre S, Calvo-Garrido J, Bloomfield G, Skelton J, Kay RR, Ivens A, Martinez JL, Escalante R. Dictyostelium transcriptional responses to Pseudomonas aeruginosa:common and specific effects from PAO1 and PA14 strains. BMC Microbiology, 2008, 8(1): 109. |

| [47] | Essig A, Heinemann M, Simnacher U, Marre R. Infection of Acanthamoeba castellanii by Chlamydia pneumoniae. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 1997, 63(4): 1396-1399. DOI:10.1128/AEM.63.4.1396-1399.1997 |

| [48] | DiSalvo S, Haselkorn TS, Bashir U, Jimenez D, Brock DA, Queller DC, Strassmann JE. Burkholderia bacteria infectiously induce the proto-farming symbiosis of Dictyostelium amoebae and food bacteria. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2015, 112(36): E5029-E5037. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1511878112 |

| [49] | Thomas JM, Ashbolt NJ. Do free-living amoebae in treated drinking water systems present an emerging health risk?. Environmental Science & Technology, 2011, 45(3): 860-869. |

| [50] | Thomas V, Herrera-Rimann K, Blanc DS, Greub G. Biodiversity of amoebae and amoeba-resisting bacteria in a hospital water network. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2006, 72(4): 2428-2438. |

| [51] | Ray K, Marteyn B, Sansonetti PJ, Tang CM. Life on the inside:the intracellular lifestyle of cytosolic bacteria. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 2009, 7(5): 333-340. DOI:10.1038/nrmicro2112 |

| [52] | Casadevall A. Evolution of intracellular pathogens. Annual Review of Microbiology, 2008, 62: 19-33. DOI:10.1146/annurev.micro.61.080706.093305 |

| [53] | Paquet VE, Charette SJ. Amoeba-resisting bacteria found in multilamellar bodies secreted by Dictyostelium discoideum:social amoebae can also package bacteria. FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 2016, 92(3): fiw025. |

| [54] | Lienard J, Greub G. Discovering new pathogens: amoebae as tools to isolate amoeba-resisting microorganisms from environmental samples//Sen K, Ashbolt NJ. Environmental Microbiology: Current Technology and Water Applications. Norfolk: Caister Academic Press, 2011: 143-162. |

| [55] | Levitte S, Adams KN, Berg RD, Cosma CL, Urdahl KB, Ramakrishnan L. Mycobacterial acid tolerance enables phagolysosomal survival and establishment of tuberculous infection in vivo. Cell Host & Microbe, 2016, 20(2): 250-258. |

| [56] | Gerstenmaier L, Pilla R, Herrmann L, Herrmann H, Prado M, Villafano GJ, Kolonko M, Reimer R, Soldati T, King JS, Hagedorn M. The autophagic machinery ensures nonlytic transmission of mycobacteria. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2015, 112(7): E687-E692. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1423318112 |

| [57] | Hilbi H, Weber SS, Ragaz C, Nyfeler Y, Urwyler S. Environmental predators as models for bacterial pathogenesis. Environmental Microbiology, 2007, 9(3): 563-575. DOI:10.1111/j.1462-2920.2007.01238.x |

| [58] | Lamoth F, Greub G. Amoebal pathogens as emerging causal agents of pneumonia. FEMS Microbiology Reviews, 2010, 34(3): 260-280. DOI:10.1111/j.1574-6976.2009.00207.x |

| [59] | H?gele S, K?hler R, Merkert H, Schleicher M, Hacker J, Steinert M. Dictyostelium discoideum:a new host model system for intracellular pathogens of the genus Legionella. Cellular Microbiology, 2000, 2(2): 165-171. DOI:10.1046/j.1462-5822.2000.00044.x |

| [60] | Horwitz MA. The Legionnaires' disease bacterium (Legionella pneumophila) inhibits phagosome-lysosome fusion in human monocytes. Journal of Experimental Medicine, 1983, 158(6): 2108-2126. DOI:10.1084/jem.158.6.2108 |

| [61] | Horwitz MA, Maxfield FR. Legionella pneumophila inhibits acidification of its phagosome in human monocytes. Journal of Cell Biology, 1984, 99(6): 1936-1943. DOI:10.1083/jcb.99.6.1936 |

| [62] | Wintermeyer E, Ludwig B, Steinert M, Schmidt B, Fischer G, Hacker J. Influence of site specifically altered Mip proteins on intracellular survival of Legionella pneumophila in eukaryotic cells. Infection and Immunity, 1995, 63(12): 4576-4583. DOI:10.1128/IAI.63.12.4576-4583.1995 |

| [63] | Gao LY, Kwaik YA. Activation of caspase 3 during Legionella pneumophila-induced apoptosis. Infection and Immunity, 1999, 67(9): 4886-4894. DOI:10.1128/IAI.67.9.4886-4894.1999 |

| [64] | Francione L, Smith PK, Accari SL, Taylor PE, Bokko PB, Bozzaro S, Beech PL, Fisher PR. Legionella pneumophila multiplication is enhanced by chronic AMPK signalling in mitochondrially diseased Dictyostelium cells. Disease Models & Mechanisms, 2009, 2(9/10): 479-489. |

| [65] | Li ZR, Dugan AS, Bloomfield G, Skelton J, Ivens A, Losick V, Isberg RR. The amoebal MAP kinase response to Legionella pneumophila is regulated by DupA. Cell Host & Microbe, 2009, 6(3): 253-267. |

| [66] | Wernegreen JJ. Endosymbiosis. Current Biology, 2012, 22(14): 555-561. DOI:10.1016/j.cub.2012.06.010 |

| [67] | Sachs JL, Skophammer RG, Regus JU. Evolutionary transitions in bacterial symbiosis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2011, 108(S2): 10800-10807. |

| [68] | Nyholm SV, McFall-Ngai M. The winnowing:establishing the squid-vibrio symbiosis. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 2004, 2(8): 632-642. DOI:10.1038/nrmicro957 |

| [69] | Friesen ML, Porter SS, Stark SC, Von Wettberg EJ, Sachs JL, Martinez-Romero E. Microbially mediated plant functional traits. Annual Review of Ecology, Evolution, and Systematics, 2011, 42: 23-46. DOI:10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-102710-145039 |

| [70] | Oliver KM, Degnan PH, Burke GR, Moran NA. Facultative symbionts in aphids and the horizontal transfer of ecologically important traits. Annual Review of Entomology, 2010, 55: 247-266. DOI:10.1146/annurev-ento-112408-085305 |

| [71] | Kikuchi Y, Meng XY, Fukatsu T. Gut symbiotic bacteria of the genus Burkholderia in the broad-headed bugs Riptortus clavatus and Leptocorisa chinensis (Heteroptera:Alydidae). Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2005, 71(7): 4035-4043. DOI:10.1128/AEM.71.7.4035-4043.2005 |

| [72] | Garcia JR, Laughton AM, Malik Z, Parker BJ, Trincot C, Chiang SSL, Chung E, Gerardo NM. Partner associations across sympatric broad-headed bug species and their environmentally acquired bacterial symbionts. Molecular Ecology, 2014, 23(6): 1333-1347. |

| [73] | Stopnisek N, Zühlke D, Carlier A, Barberán A, Fierer N, Becher D, Riedel K, Eberl L, Weisskopf L. Molecular mechanisms underlying the close association between soil Burkholderia and fungi. The ISME Journal, 2016, 10(1): 253-264. DOI:10.1038/ismej.2015.73 |

| [74] | Brock DA, Callison Wé, Strassmann JE, Queller DC. Sentinel cells, symbiotic bacteria and toxin resistance in the social amoeba Dictyostelium discoideum. Proceedings of the Royal Society B:Biological Sciences, 2016, 283(1829): 20152727. DOI:10.1098/rspb.2015.2727 |

| [75] | Stallforth P, Brock DA, Cantley AM, Tian XJ, Queller DC, Strassmann JE, Clardy J. A bacterial symbiont is converted from an inedible producer of beneficial molecules into food by a single mutation in the gacA gene. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2013, 110(36): 14528-14533. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1308199110 |

| [76] | Brock DA, Read S, Bozhchenko A, Queller DC, Strassmann JE. Social amoeba farmers carry defensive symbionts to protect and privatize their crops. Nature Communications, 2013, 4(1): 2385. DOI:10.1038/ncomms3385 |

| [77] | Stout JD. The role of protozoa in nutrient cycling and energy flow//Marshall KC. Advances in Microbial Ecology. New York: Plenum Press, 1980: 1-50. |

| [78] | Clarholm M. Protozoan grazing of bacteria in soil-impact and importance. Microbial Ecology, 1981, 7(4): 343-350. |

| [79] | Coleman DC, Anderson RV, Cole CV, Elliott ET, Woods L, Campion MK. Trophic interactions in soils as they affect energy and nutrient dynamics. Ⅳ. Flows of metabolic and biomass carbon. Microbial Ecology, 1977, 4(4): 373-380. |

| [80] | Clarholm M. Interactions of bacteria, protozoa and plants leading to mineralization of soil nitrogen. Soil Biology and Biochemistry, 1985, 17(2): 181-187. DOI:10.1016/0038-0717(85)90113-0 |

| [81] | Storey MV, Winiecka-krusnell J, Ashbolt NJ, Stenstr?m TA. The efficacy of heat and chlorine treatment against thermotolerant Acanthamoebae and Legionellae. Scandinavian Journal of Infectious Diseases, 2004, 36(9): 656-662. DOI:10.1080/00365540410020785 |

| [82] | Simek K, Vrba J, Pernthaler J, Posch T, Hartman P, Nedoma J, Psenner R. Morphological and compositional shifts in an experimental bacterial community influenced by protists with contrasting feeding modes. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 1997, 63(2): 587-595. |

| [83] | Sherr BF, Sherr EB, Hopkinson CS. Trophic interactions within pelagic microbial communities:indications of feedback regulation of carbon flow. Hydrobiologia, 1988, 159(1): 19-26. DOI:10.1007/BF00007364 |

| [84] | Al-Shahwani SM, Horan NJ. The use of protozoa to indicate changes in the performance of activated sludge plants. Water Research, 1991, 26(6): 633-638. |

| [85] | Curds CR. The ecology and role of protozoa in aerobic sewage treatment processes. Annual Review of Microbiology, 1982, 36: 27-28. DOI:10.1146/annurev.mi.36.100182.000331 |

| [86] | Jeon KW, Lorch IJ. Unusual intra-cellular bacterial infection in large, free-living amoebae. Experimental Cell Research, 1967, 48(1): 236-240. DOI:10.1016/0014-4827(67)90313-8 |

| [87] | Delafont V, Bouchon D, Héchard Y, Moulin L. Environmental factors shaping cultured free-living amoebae and their associated bacterial community within drinking water network. Water Research, 2016, 100: 382-392. DOI:10.1016/j.watres.2016.05.044 |

| [88] | Hall J, Voelz H. Bacterial endosymbionts of Acanthamoeba sp.. The Journal of Parasitology, 1985, 71(1): 89-95. |

| [89] | Horn M, Wagner M. Bacterial endosymbionts of free-living amoebae. Journal of Eukaryotic Microbiology, 2004, 51(5): 509-514. DOI:10.1111/j.1550-7408.2004.tb00278.x |

| [90] | Schulz F, Horn M. Intranuclear bacteria:inside the cellular control center of eukaryotes. Trends in Vell Biology, 2015, 25(6): 339-346. DOI:10.1016/j.tcb.2015.01.002 |

| [91] | Schulz F, Lagkouvardos I, Wascher F, Aistleitner K, Kostanj?ek R, Horn M. Life in an unusual intracellular niche:a bacterial symbiont infecting the nucleus of amoebae. The ISME Journal, 2014, 8(8): 1634-1644. DOI:10.1038/ismej.2014.5 |