, 张丽萍1, 张鑫1, 孙建树1, 李婉婷1, 郭芳丽1, 吴莎1

, 张丽萍1, 张鑫1, 孙建树1, 李婉婷1, 郭芳丽1, 吴莎11. 曲阜师范大学地理与旅游学院, 日照 276826;

2. 清华大学环境学院, 北京 100084

收稿日期: 2017-08-23; 修回日期: 2017-11-26; 录用日期: 2017-11-28

基金项目: 国家自然科学基金(No.41301532);国家级大学生创新创业训练计划项目(No.201610446088);国家水体污染控制与治理科技重大专项(No.2012ZX07301-001);中国博士后科学基金一等资助项目(No.2013M540103)

作者简介: 王世亮(1979—), 男, E-mail: wangshiliang@tsinghua.org.cn

通讯作者(责任作者): 王世亮(1979—), 男, 副教授, 硕士生导师, 长期从事水土环境化学领域的研究, 发表SCI论文30余篇. E-mail: wangshiliang@tsinghua.org.cn

摘要: 为探究河流水体和污水厂出水中全氟烷基酸(Perfluoroalkyl Acids,PFAAs)及其前体物的污染特征,采用羟基自由基氧化、WAX固相萃取分离富集、超高效液相色谱-质谱串联相结合的方法,以泗河水体及其附近污水厂出水为例,对上述不同水体中的PFAAs及其前体物的空间分布特征及前体物对水体污染的贡献进行了系统研究.结果表明,泗河水体和附近污水厂出水中PFAAs的总浓度(∑PFAAs)分别为3.87~40.84和55.59~110.91 ng·L-1,均值分别为24.92和88.04 ng·L-1;PFOS、PFHxS、PFOA、PFHxA和PFNA是浓度较高的污染物;污水厂出水中PFAAs的浓度明显高于泗河,泗河上游水体PFAAs的浓度低于下游.在对水样进行氧化处理后,泗河水体中碳原子数为4~12的全氟羧酸类化合物(Perfluorinated Carboxylic Acids,PFCAs)浓度增加值(∑Δ[PFCAC4-12])低于附近污水厂出水,但污水厂出水中前体物的转化率(Δ[PFCAs]/[PFCAs]氧化前)低于泗河水体,因此,污水处理过程中可能存在前体物的降解.

关键词:全氟烷基酸前体物污染水平泗河

Characteristics of spatial distribution of perfluoroalkyl acids (PFAAs) and their precursors in the water samples from the Sihe River and the effluents of wastewater treatment plants

WANG Shiliang1,2

, ZHANG Liping1, ZHANG Xin1, SUN Jianshu1, LI Wanting1, GUO Fangli1, WU Sha1

, ZHANG Liping1, ZHANG Xin1, SUN Jianshu1, LI Wanting1, GUO Fangli1, WU Sha1 1. School of Geography and Tourism, Qufu Normal University, Rizhao 276826;

2. School of Environment, Tsinghua University, Beijing 100084

Received 23 August 2017; received in revised from 26 November 2017; accepted 28 November 2017

Supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China(No.41301532), the National Innovation and Entrepreneurship Training Program for College Students of China (No.201610446088), the National Major Science and Technology Program for Water Pollution Control and Treatment(No.2012ZX07301-001) and the First Class General Financial Grant from the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation(No.2013M540103)

Biography: WANG Shiliang (1979—), male, E-mail: wangshiliang@tsinghua.org.cn

*Corresponding author: WANG Shiliang, E-mail: wangshiliang@tsinghua.org.cn

Abstract: In order to investigate the pollution characteristics of perfluoroalkyl acids (PFAAs) and their precursors in the river water and the effluents of sewage treatment plants (STPs), the spatial distribution characteristics of PFAAs and their precursors and the contributions of these precursors to water contamination were systematically investigated based on the methods including the hydroxyl radical (·OH) oxidation, the solid phase extraction and enrichment, and the ultra-performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS/MS), take the Sihe River and the local sewage treatment plants (STPs) for example. The results indicated that the total concentrations of PFAAs (∑PFAAs) in the water samples of the Sihe River and the STPs effluents were in the range of 3.87~40.84 ng·L-1 and 55.59~110.91 ng·L-1, and averaged 24.92 ng·L-1 and 88.04 ng·L-1, respectively. The most prevalent PFAAs for all the water samples were PFOS, PFHxS, PFOA, PFHxA, and PFNA. The PFAAs concentrations in the STP effluent samples were obviously higher than those in the Sihe River. In addition, the total concentrations of PFAAs in the water samples from the upstream of Sihe River were lower than those from the downstream. After oxidation treatment of the water samples, the increased concentrations of the perfluorinated carboxylic acids (PFCAs) with 4~12 perfluoroalkyl carbon chains (∑Δ[PFCAC4-12]) in the Sihe River were lower than those in the STP effluents. But the ratios of the compounds formed against PFCAs originally present (Δ[PFCAs]/[PFCAs]) in the STP effluents were lower than those in the Sihe River, which indicated the degradation of precursors during the sewage treatment processes.

Key words: perfluoroalkyl acidsprecursorspollution levelSihe River

1 引言(Introduction)作为一类新型有机污染物, 全氟烷基酸类化合物(Perfluoroalkyl Acids, PFAAs)在环境中具有较高的化学稳定性、生物积聚性及较难生物降解的特征(Giesy et al., 2002), 近几十年来被广泛用于工业生产和日常生活等众多领域.在其生产和使用过程中, PFAAs通过多种途径进入地表水体(王鑫璇等, 2014; Wang et al., 2015)和沉积物(巩秀贤等, 2015)中.研究发现, PFAAs能对生物肝脏、免疫、生殖发育及神经系统等产生明显毒性效应(Hekster et al., 2003).由于其在环境中的稳定性、生物毒性、持久性及长距离传输性, PFAAs已成为一种典型的全球性污染物.2009年5月, 全氟辛烷磺酸(Perfluorooctane Sulfonate, PFOS)及其盐类和全氟辛基磺酰氟(Perfluorooctane Sulfonyl Fluoride, POSF)被列入《斯德哥尔摩公约》, 并在全球范围内被限制生产和使用.由于大部分PFAAs具有较高的水溶性和较强的表面活性, 这类物质能在各种水体中大量累积(张大文等, 2012).传统的污水处理工艺对PFAAs并没有很好的去除效果, 而且由于某些PFAAs前体物和中间产物的生物降解, 二级生物处理技术能显著增加出水中的全氟辛酸(Perfluorooctanonic Acid, PFOA)和PFOS浓度(And et al., 2006).

众多研究也表明, PFAAs前体物和中间产物在环境中也广泛存在, 如氟调聚醇(Fluorotelomer Alcohols, FTOHs)、全氟辛烷磺酰胺(Perfluorooctanesulfonamide, FOSA), 8: 2氟调聚物不饱和酸(8: 2 Fluorotelomer Unsaturated Acid, 8: 2 FTUCA)和全氟辛基磺胺乙醇磷酸酯(Diperfluorooctane Sulfonamido Ethanol-Based Phosphate, di-SAmPAP)在水、沉积物及人体血清中均被检出(Lee et al., 2011;Sun et al., 2011;Zushi et al., 2011;Ye et al., 2015;刘宝林等, 2015).PFAAs前体物和中间产物的转化也是环境中PFAAs的一个潜在来源(Xu et al., 2004;Rhoads et al., 2008), 如FOSA可以降解产生PFOS.许多含氟调基的全氟聚合物最终降解为PFCAs(Butt et al., 2014);挥发性前体物在大气中发生光化学转化生成PFAAs, 因此, 大气长距离迁移和光化学转化被认为是偏远地区地表环境中PFAAs的重要来源(姚义鸣等, 2016).然而由于缺乏相应的分析方法和技术, 目前只能直接测得少数几种前体物, 而许多潜在的物质, 如含氟聚合物还不能直接进行分析(Houtz et al., 2012).此外, 目前关于水环境中前体物的含量及空间分布的研究还非常缺乏, 已有的研究工作主要还是处于前期的探索阶段, 如运用羟基自由基氧化法对城市径流中PFAAs前体物的含量进行分析监测, 通过对比氧化前后溶液中特定碳链长度化合物的浓度, 即可推导出其前体物的浓度(Houtz et al., 2012; Ye et al., 2014), 这些研究工作都表明前体物的转化是水环境中PFAAs污染的潜在重要来源.

泗河发源于山东省泗水县, 流经泗水县、曲阜市、兖州市、济宁市, 最后注入南四湖, 流域内矿产资源丰富, 工农业发达, 特别以矿产开采、冶炼、医药、氟化工等工业为特色.泗河上游河段位于泗水县境内, 以农业生产为主, 下游河段流经兖州和济宁, 深受工矿业发展的影响.因此, 泗河上下游水体污染程度具有明显差异, 而且该河流是附近唯一的纳污河道, 周边污水厂出水最终也排入泗河.

因此, 本研究以泗河水体及周边污水厂出水为研究对象, 对上述水体中PFAAs及其前体物的含量水平及空间分布和PFAAs前体物的转化潜力进行系统研究, 以期为该区域水环境污染现状调查提供基础数据资料.

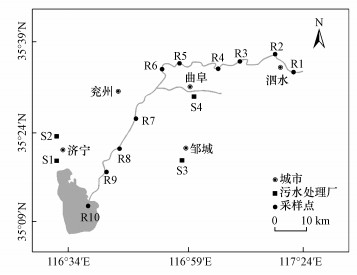

2 采样和分析(Samples and analysis)2.1 样品采集2014年5月, 在泗河的10个采样点(R1~R10)和以泗河为纳污水体的附近4个污水厂(S1~S4)出水口采集水样(图 1), 泗河的每个采样点用5 L的有机玻璃采水器采集0~20 cm的表层水, 污水厂水样在其排水口采集, 为了去除水体中的悬浮颗粒物, 采集的水样用经过预处理的Whatman玻璃纤维滤膜(1.2 μm)过滤, 过滤的水样装入事先用甲醇和去离子水依次润洗过的高密度聚乙烯(HDPE)瓶中.各采样点的空白样品为超纯水, 与采集的水样同时装入预处理后的HDPE瓶中, 保存条件与水样相同.样品采集和实验过程中未使用任何含聚四氟乙烯的材料, 以防止可能的PFAAs污染.

图 1(Fig. 1)

|

| 图 1 采样点位置示意图 Fig. 1Schematic graph of the sampling sites |

2.2 试剂与材料实验试剂:本研究所使用的标准品包括全氟丁酸(PFBA)、全氟戊酸(PFPA)、全氟己酸(PFHxA)、全氟庚酸(PFHpA)、全氟辛酸(PFOA)、全氟壬酸(PFNA)、全氟癸酸(PFDA)、全氟十一酸(PFUnDA)、全氟十二酸(PFDoDA)、全氟十三酸(PFTrDA)、全氟十四酸(PFTeDA)、全氟丁烷磺酸(PFBS)、全氟己烷磺酸(PFHxS)、全氟辛烷磺酸(PFOS)、全氟癸烷磺酸(PFDS)、8: 2调聚全氟辛基羧酸酯(8: 2FTCA)、全氟辛基磺酰胺(FOSA)、全氟辛基磺胺乙醇磷酸酯(di-SAmPAP), 以及内标物[13C4]PFBA、[13C2]PFHxA、[13C4]PFOA、[13C5]PFNA、[13C2]PFDA、[13C2]PFUnDA、[13C2]PFDoDA、[18O2]PFHxS、[13C4]PFOS, 以上标准样品全部购自加拿大Wellington公司, 纯度均大于98%;实验用甲醇为色谱纯级, 购自美国Tedia公司;实验过程中使用的超纯水均为实验室制备.

实验仪器及测试条件:超高液相色谱串联质谱联用仪(UPLC-MS/MS, Waters Acquity UPLC-Quattro Premier XE型), 弱阴离子交换柱(WAX柱, Qasis? WAX, 6 cc, 150 mg, 30 μm), 玻璃纤维滤膜(1.2 μm, Whatman公司);Agilent聚丙烯液相小瓶(1 mL);氮吹仪(Organomation Associates公司, 加拿大);Amberlite XAD-2树脂(Supleco, 美国).

超高效液相色谱:Waters BEH-C18的色谱柱(2.1 mm×50 mm, 1.7 μm), 流动相A为含2 mmol乙酸铵的水和甲醇混合液(98: 2), 流动相B为含2 mmol乙酸铵的甲醇溶液, 色谱柱的温度为40 ℃, 流速为0.30 mL·min-1, 进样量为5 μL.

质谱:电喷雾离子源, 负离子模式(ESI-), 多反应离子监测(MRM), 辅助气(N2)流速10 mL·min-1, 碰撞气(Ar)流速0.18 mL·min-1, 雾化温度380 ℃, 离子源温度120 ℃.

2.3 样品前处理水样经过滤后进行预处理, 具体过程参考Taniyansu等(2008)的方法进行, 加入内标的水样混匀后用Waters的WAX小柱进行所测物质的富集.具体过程如下:依次用含氨水(0.1%, 4 mL)的甲醇溶液、甲醇(4 mL)、水(4 mL)进行活化, 然后将10 ng相应内标加入到1.0 L已经过滤的水样中并摇匀, 将该水样流过WAX小柱(1.0 mL·min-1的速度), 使全氟化合物吸附在WAX小柱上.水样过滤完毕后, 用醋酸盐缓冲液(25 mmol·L-1, pH=4, 4 mL)冲洗WAX小柱, 然后将该小柱离心除去残留的水, 用甲醇(4 mL)和含氨水(0.1%, 4 mL)的甲醇溶液对目标化合物进行洗脱, 洗脱液经氮吹后, 用流动相定容至1.0 mL, 最后进行UPLC-MS/MS测定.

2.4 样品氧化处理基于羟基自由基氧化对样品中PFAAs前驱物的转化能力进行定量化分析(Houtz et al., 2012; Ye et al., 2014).利用过硫酸盐(S2O82-)在碱性条件下热解产生的羟基自由基(·OH)将前体物氧化, 对比氧化前后溶液中PFAAs的浓度, 可以确定前体物的浓度.羟基自由基氧化由于操作简单, 不需要特定的仪器设备, 对后续分析产生的影响较小, 因而与其它高级氧化方法相比具有一定的优势.具体操作如下:向装有未过滤水样的125 mL HDPE瓶中加入2 mL过硫酸盐(60 mmol·L-1)和1.9 mL氢氧化钠(150 mmol·L-1), 每个采样点的水样1式3份, 将HDPE瓶放置于油浴锅中85 ℃加热6 h, 冷却至室温.

2.5 质量保证与控制为了排除样品采集和处理过程中可能造成的污染, 保证实验的准确性, 以不受PFAAs污染的超纯水作为实验基质, 进行全程空白对照, 实验所用实验器皿均为聚丙烯材质, 使用前用甲醇和超纯水进行淋洗.在空白水样中(1 L)加入所有待测物的标准溶液(10 ng)混标和内标物质(10 ng), 按照与样品同样的仪器条件和处理过程进行回收率检测.水样中各待测物的加标回收率为73.95%~103.42%, 相对标准偏差范围为2.47%~6.72%.水样中的PFASs的检测限为0.06~0.18 ng·L-1, 空白对照样品中未检出PFASs.

2.6 数据统计本文应用SPASS 13.0对实验数据进行处理分析.

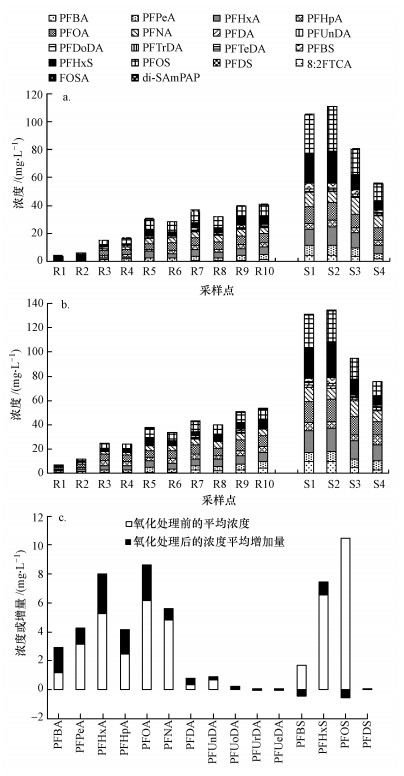

3 结果与讨论(Results and discussion)3.1 泗河和污水厂出水中PFAAs的含量和空间分布泗河和污水厂出水中15种PFAAs(C4-14PFCAs和C4, 6, 8, 10PFSAs)及3种前体物(8: 2 FTCAs、FOSA和di-SAmPAP)的浓度测定结果如图 2所示.泗河水体中, ∑PFAAs浓度在3.87~40.84 ng·L-1之间, 平均值为24.92 ng·L-1;浓度最高的5种物质分别是PFOS(0.72~8.51 ng·L-1, 平均值5.57 ng·L-1)、PFOA(0.65~6.47 ng·L-1, 平均值4.25 ng·L-1)、PFHxA(0.32~5.49 ng·L-1, 平均值3.15 ng·L-1)、PFHxS(0.58~6.21 ng·L-1, 平均值3.04 ng·L-1)和PFNA(0.36~4.92 ng·L-1, 平均值2.91 ng·L-1).其中, PFOS和PFOA是泗河水体中浓度最高的2种污染物, 而且PFOS的浓度明显高于PFOA.

图 2(Fig. 2)

|

| 图 2 氧化前后PFAAs(n=15)及其前体物(n=3)的浓度(a.氧化前, b.氧化后)及PFAAs同系物的平均浓度(c) Fig. 2Concentrations of perfluoroalkyl acids (PFAAs) and their precursors before and after oxidation treatment(a.before oxidation treatment, b. after oxidation treatment) and the average concentrations of individual PFAAs homologs for all samples(c) |

在从泗河上游到下游的10个采样点中, ∑PFAAs浓度从点R1到R10呈逐渐升高的趋势(图 2a).采样点R1和R2的∑PFAAs浓度最低, 分别为3.76和5.72 ng·L-1, R1~R4采样点的∑PFAAs浓度平均值为10.12 ng·L-1;采样点R5~R10位于泗河下游, ∑PFAAs浓度的平均值为34.37 ng·L-1.因此, 泗河下游河段水体中∑PFAAs值明显高于上游河段.这种差异可能与河流下游接纳工业污染物排放有关.研究表明, 水中溶解的全氟化合物浓度与人口密度有显著相关关系(Ye et al., 2014).此外, 区域工业发展程度和居民生活与全氟化合物的污染可能也密切相关(Giesy et al., 2002).农业化学品、表面活性剂、化妆品、食品包装、泡沫灭火剂、电子产品、药物生产、电镀、聚合物添加剂等与人类生活密切相关的许多产品都能导致全氟化合物的污染.泗河为该流域的主要纳污水体, 流域的主要工农业废水主要经泗河流入南四湖, 而泗河上游主要为农田, 没有工业污染, 下游流经区域分布着众多城区和工业区, 接纳了大量城市生活污水、工业污染物和污水厂排水.因此, 流域工农业发展状况及污水厂排水对泗河水体中PFAAs含量的空间分布有重要影响.

本研究所调查的附近污水厂出水最终都注入泗河, 出水中∑PFAAs浓度范围为55.67~110.91 ng·L-1, 平均浓度为88.04 ng·L-1.相关研究显示, 沈阳、南京、大连和广州的污水厂出水∑PFAAs及其前体物的浓度水平与本研究结果相似(Zhang et al., 2013), 但比受氟化物严重污染影响的日本东京湾盆地水体的浓度低得多(Zushi et al., 2011).本研究涉及的污水厂出水中, 浓度最高的几种PFAAs分别是PFOS(12.19~31.73 ng·L-1, 平均为22.69 ng·L-1)、PFHxS(6.78~22.84 ng·L-1, 平均为15.35 ng·L-1)、PFOA(9.32~12.86 ng·L-1, 平均为10.9 ng·L-1)、PFHxA(6.08~13.64 ng·L-1, 平均为10.48 ng·L-1)和PFNA(7.83~11.98 ng·L-1, 平均为9.56 ng·L-1).通过上述几种物质浓度均值比较发现, 污水厂出水的值比泗河水体高0~13.9倍.所以, 污水厂的排水对作为其纳污河道的泗河水体PFAAs含量有重要贡献.

3.2 泗河和污水厂出水中PFAAs前体物的浓度和空间分布对泗河和污水厂出水中8: 2 FTCA、FOSA、di-SAmPAP 3种物质进行了分析测试, 结果(图 2)表明, 泗河水体和污水厂出水中前体物的总浓度范围分别为0.11~0.57和0.08~0.15 ng·L-1, 平均浓度分别为0.26和0.11 ng·L-1, 泗河水体中的值都高于污水厂出水的相应值, FOSA浓度明显高于其它前体物, 此结果与日本东京主要河流的研究结果一致(Zushi et al., 2011).

基于羟基自由基氧化将水体中PFAAs潜在前体物进行氧化转化, 氧化处理后水体中存在的PFCAs包括氧化前已经存在的和经氧化转化产生的两部分污染物(Ye et al., 2014).前体物是环境中PFAAs的潜在来源, 氧化处理后与处理前PFAAs的浓度差可用来指示PFAAs前体物的含量(Houtz et al., 2012).本研究中泗河水体和污水厂出水中, 氧化处理后PFAAs增加的浓度分析结果如表 1所示.所有采样点中, PFHxA、PFOA、PFBA、PFHpA和PFPeA是浓度均值增加最多的几种物质.泗河和污水厂出水中PFOA浓度增加的均值分别为1.63和4.61 ng·L-1;据此结果推断, 如果氧化之前直接测得的PFAAs前体物以97%的转化率转化为PFOA, 那么泗河和污水厂出水中PFOA的平均浓度分别增加0.25、0.10 ng·L-1, 这一数值显然小于氧化处理的实际增加浓度.这说明除了文中检测到的目标前体物之外, 还存在其他一些未知的可以转化为PFOA的前体物质.

表 1(Table 1)

| 表 1 氧化处理后PFCAs增加的浓度(Δ[PFCAs]) Table 1 Increased concentration of perfluorinated carboxylic acids upon oxidation of PFAA precursors in samples (Δ[PFCAs]) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

表 1 氧化处理后PFCAs增加的浓度(Δ[PFCAs]) Table 1 Increased concentration of perfluorinated carboxylic acids upon oxidation of PFAA precursors in samples (Δ[PFCAs])

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

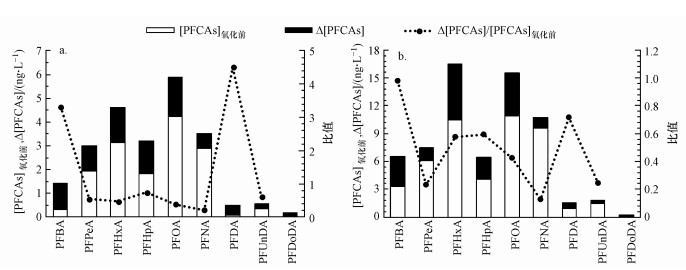

泗河水体中PFCAs增加的总浓度(∑Δ[PFCAC4-12])为3.51~13.21 ng·L-1 (表 1, 图 3), 平均值为8.04 ng·L-1;平均增加浓度最多的5种PFCAs分别为PFOA(1.63 ng·L-1)、PFHxA(1.47 ng·L-1)、PFHpA(1.36 ng·L-1)、PFBA(1.10 ng·L-1)和PFPeA(1.05 ng·L-1), 即水体样品氧化后C4~C8链的PFCAs平均浓度增加最多, 明显高于C9~C12链的PFCAs, 这可能是由于氧化过程中各种前体物更多的转化为短链PFCAs, 如很多研究都证明8: 2 FTOH最终降解生成PFOA(Murakami et al., 2009;Butt et al., 2014);在污水处理过程中PFAAs前体物的生物降解最终生成PFOA(Murakami et al., 2009;Shivakoti et al., 2010;Sun et al., 2012).

图 3(Fig. 3)

|

| 图 3 氧化前PFCAs的平均浓度([PFCAs]氧化前)、PFCAs氧化增加的浓度(Δ[PFCAs])及[PFCAs]氧化前与Δ[PFCAs]的比值 (a.泗河样品, b.污水厂出水样品) Fig. 3Average concentrations of individual PFCAs before oxidation treatment ([PFCAs]before oxidation), the increased concentrations of PFCAs (Δ[PFCAs]) after the oxidation treatment, and the ratios of Δ[PFCAs] to [PFCAs]before oxidation (a.Water samples from Sihe River, b.Samples from sewage treatment plants (STPs) effluents) |

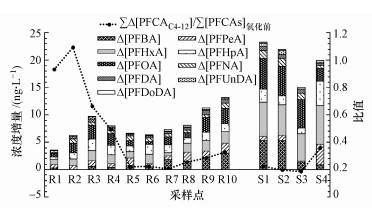

泗河水体∑Δ[PFCAC4-12]的空间分布状况如图 4所示, 结果显示, ∑Δ[PFCAC4-12]沿河流流向整体呈上升的趋势.采样点R1的∑Δ[PFCAC4-12]最低, 为3.51 ng·L-1, 采样点R10的∑Δ[PFCAC4-12]最高, 为13.21 ng·L-1.泗河上游河段各点(R1~R4)平均∑Δ[PFCAC4-12]为6.88 ng·L-1, 下游河段各点(R5~R10)平均为8.81 ng·L-1, 下游河段各采样点的平均∑Δ[PFCAC4-12]明显高于上游河段.

图 4(Fig. 4)

|

| 图 4 各采样点水样氧化处理后PFCAs增加的浓度(Δ[PFCAs])及增加浓度总和(∑Δ[PFCAC4-12])与氧化前PFCAs的浓度([PFCAs]氧化前)之比 Fig. 4Increased concentrations of individual PFCAs after oxidation treatment (Δ[PFCAs]) and the ratios of ∑Δ[PFCAC4-12] to [PFCAs]before oxidation in water samples for all sampling sites |

污水厂出水∑Δ[PFCAC4-12]如表 1和图 4所示.点S1、S2、S3和S4的∑Δ[PFCAC4-12]分别为23.34、21.94、14.96和19.97 ng·L-1, 平均值为20.05 ng·L-1.污水厂出水∑Δ[PFCAC4-12]的平均值明显高于泗河水体, 因此, 污水厂出水可能影响泗河水体PFAAs前体物的浓度水平.污水厂出水中, 平均增加浓度最大的5种PFCAs分别是PFHxA (6.00 ng·L-1)、PFOA (4.61 ng·L-1)、PFBA (3.22 ng·L-1)、PFHpA (2.39 ng·L-1)和PFPeA (1.40 ng·L-1), 这一结果与泗河水体中的结果一致, 是因为氧化过程中各种前体物更快的转化为较短链的PFCAs.

通过对各采样点PFCAs的各同系物氧化处理后增加的浓度与氧化前浓度的比值(Δ[PFCAs]/[PFCAs]氧化前)进行分析, 结果如表 2和图 4所示.污水厂出水的Δ[PFCAs]/[PFCAs]氧化前的值低于泗河水体, 但Δ[PFCAs]普遍高于泗河水体.Δ[PFCAs]较高, 但比值较低, 这可能是由于污水处理过程中存在前体物的降解所致(Ye et al., 2014).如表3所示, 泗河水体和污水厂出水中, PFBA的Δ[PFCAs]/[PFCAs]氧化前最高, 这是因为PFDA的初始浓度相对较低, 且PFBA的全氟碳链相对较短, 会由更多长碳链的前体物转化而成(Houtz et al., 2012; Ye et al., 2014).泗河水体中, PFDA的Δ[PFCAs]/[PFCAs]氧化前比值最高, 这可能是由于PFDA的初始浓度较低, 而泗河水体中又有比较重要的PFDA前体物的排放源, 使得PFDA的氧化转换量较大所致.

表 2(Table 2)

| 表 2 氧化处理后PFCA增加的浓度(Δ[PFCAs])与氧化前PFCA([PFCAs]氧化前)的浓度比值 Table 2 The ratio of the increased concentration of perfluorinated carboxylic acids upon oxidation of PFAA precursors in samples after oxidation treatment and the concentration of individual PFCAs ([PFCAs]before oxidation) before oxidation treatment | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

表 2 氧化处理后PFCA增加的浓度(Δ[PFCAs])与氧化前PFCA([PFCAs]氧化前)的浓度比值 Table 2 The ratio of the increased concentration of perfluorinated carboxylic acids upon oxidation of PFAA precursors in samples after oxidation treatment and the concentration of individual PFCAs ([PFCAs]before oxidation) before oxidation treatment

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

3.3 PFAAs的来源分析利用全氟化合物同系物之间的比值, 如PFOS/PFOA、PFHpA/PFOA、PFOA/PFNA的浓度比, 可以确定PFAAs的可能潜在来源(Simcik et al., 2005; So et al., 2004);如PFOS/PFOA大于1.0, 说明可能存在PFAAs的点源污染, 如污水厂出水(So et al., 2004; Wang et al., 2012; Guo et al., 2015).本研究涉及泗河水体PFOS/PFOA的范围为0.99~1.47, 这一数值大于南四湖(Cao et al., 2015)、太湖(Guo et al., 2015)、密西西比河下游河段(Hansen et al., 2002)、长江(Pan et al., 2014)和朝鲜沿海水域(So et al., 2004)的相应数值, 说明泗河流域可能存在点源污染影响了该水体中PFAAs的污染状况.

此外, 很多研究还对其它同系物之间的比值进行了研究, 如受氟化物制造业直接排放影响的表层水PFOA/PFNA的浓度比为7~15(Armitage et al., 2009);当存在PFAAs的二次来源, 如挥发性前体物的降解时, 表层水PFOA/PFNA的浓度比值范围在1.7~56.8之间(Guo et al., 2015);接收挥发性前体物大气沉解的偏远地区, 其表层水中PFOA/PFNA比值大约是1.5(Cai et al., 2012).本研究中泗河水体PFOA/PFNA的比值范围为1.15~2.83, 说明在该区域可能存在PFAAs的二次来源, 如挥发性前体物的大气氧化转化和沉降影响了泗河水体中的全氟化合物的含量状况.此外, PFHpA/PFOA的浓度比也是表征挥发性前体物大气沉降的指标(Guo et al., 2015).泗河水中PFHpA/PFOA的比值范围是0.31~0.51, 接近受大气沉降影响的城市河流水体中的相应比值(0.5~0.9) (Simcik et al., 2005).以上结果说明, 挥发性前体物的大气氧化转化和沉降也可能是泗河水体PFAAs的一个来源.有关具体污染来源, 在以后的研究中可能需要更深入的探索.

4 结论(Conclusions)1) 泗河水体∑PFAAs浓度范围为3.87~40.84 ng·L-1, 平均浓度为24.92 ng·L-1;污水厂出水∑PFAAs浓度范围为55.67~110.91 ng·L-1, 平均浓度为88.04 ng·L-1.PFOS、PFOA、PFHxA、PFHxS和PFNA为含量占绝对优势的几种污染物.污水厂出水中PFAAs的平均浓度显著高于泗河, 说明污水厂出水对泗河水体中PFAAs污染有一定贡献.

2) 污水厂出水中PFAAs前体物的浓度高于泗河.氧化处理后, 泗河水体∑Δ[PFCAC4-12]范围为3.51~13.21 ng·L-1, 平均值为8.04 ng·L-1;污水厂出水中∑Δ[PFCAC4-12]范围为14.96~23.34 ng·L-1, 平均值为20.05 ng·L-1.污水厂出水的平均∑Δ[PFCAC4-12]明显高于泗河水体, 所以, 污水厂出水可能是泗河流域水体中PFAAs前体物的重要来源.

3) 空间分布上, 泗河上游水体中PFAAs浓度明显低于下游水体, 因此, PFAAs的浓度水平与周边工农业污染的汇入有密切关系;此外, 泗河∑Δ[PFCAC4-12]沿河流流向呈逐渐上升的趋势, 因此, 潜在前体物的含量也由上游到下游呈增长的趋势.

4) 全氟化合物挥发性前体物的大气氧化及沉降也可能是该流域水体中全氟化合物的一个重要来源.

参考文献

| And E S, Kannan K. 2006. Mass loading and fate of perfluoroalkyl surfactants in wastewater treatment[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 40(5): 1408–1414. |

| Armitage J M, MacLeod M, Cousins I T. 2009. Comparative assessment of the global fate and transport pathways of long-chain perfluorocarboxylic acids (PFCAs) and perfluorocarboxylates (PFCs) emitted from direct sources[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 43(15): 5830–5836. |

| Butt C M, Muir D C G, Mabury S A. 2014. Biotransformation pathways of fluorotelomer-based polyfluoroalkyl substances:a review[J]. Environmental Toxicology & Chemistry, 33(2): 243–267. |

| Cai M, Yang H, Xie Z, et al. 2012. Per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances in snow, lake, surface runoff water and coastal seawater in Fildes Peninsula, King George Island, Antarctica[J]. Journal of Hazardous Materials, 209-210(4): 335–342. |

| Cao Y X, Cao X Z, Wang H, et al. 2015. Assessment on the distribution and partitioning of perfluorinated compounds in the water and sediment of Nansi Lake, China[J]. Environmental Monitoring and Assessment, 187(10): 1–9. |

| Giesy J P, Kannan K. 2002. Peer reviewed:perfluorochemical surfactants in the environment[J]. Environment Science & Technology, 36(7): 146A–152A. |

| 巩秀贤, 李斌, 柳玉英, 等. 2015. 浑河-大辽河水系水体与沉积物中典型全氟化合物的污染水平及生态风险评价[J]. 环境科学学报, 2015, 35(7): 2177–2184. |

| Guo C S, Zhang Y, Zhao X, et al. 2015. Distribution, source characterization and inventory of perfluoroalkyl substances in Taihu Lake, China[J]. Chemosphere, 127: 201–207.DOI:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2015.01.053 |

| Hansen K J, Johnson H O, Eldridge J S, et al. 2002. Quantitative characterization of trace levels of PFOS and PFOA in the Tennessee River[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 36(8): 1681–1685. |

| Hekster F M, Laane R W, De V P. 2003. Environmental and toxicity effects of perfluoroalkylated substances[J]. Reviews of Environmental Contamination and Toxicology, 179(2): 99–121. |

| Houtz E F, Sedlak D L. 2012. Oxidative conversion as a means of detecting precursors to perfluoroalkyl acids in urban runoff[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 46(17): 9342–9349. |

| Lee H, Mabury S A. 2011. A pilot survey of legacy and current commercial fluorinated chemicals in human sera from United States donors in 2009[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 45(19): 8067–8074. |

| 刘宝林, 张鸿谢, 刘伟, 等. 2015. 深圳近岸海域全氟化合物的污染特征[J]. 环境科学, 2015, 36(6): 2028–2037. |

| Murakami M, Shinohara H, Takada H. 2009. Evaluation of wastewater and street runoff as sources of perfluorinated surfactants (PFSs)[J]. Chemosphere, 74(4): 487–493.DOI:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2008.10.018 |

| Pan C G, Ying G G, Zhao J L, et al. 2014. Spatiotemporal distribution and mass loadings of perfluoroalkyl substances in the Yangtze River of China[J]. Science of the Total Environment, 493(9): 580–587. |

| Rhoads K R, Janssen E M L, Luthy R G, et al. 2008. Aerobic biotransformation and fate of N-ethyl perfluorooctane sulfonamidoethanol (N-EtFOSE) in activated sludge[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 42(8): 2873–2878. |

| Shivakoti B R, Tanaka S, Fujii S, et al. 2010. Occurrences and behavior of perfluorinated compounds (PFCs) in several wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) in Japan and Thailand[J]. Journal of Environmental Monitoring Jem, 12(6): 1255–1264.DOI:10.1039/b927287a |

| Simcik M F, Dorweiler K J. 2005. Ratio of perfluorochemical concentrations as a tracer of atmospheric deposition to surface waters[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 39(22): 8678–8683. |

| So M K, Taniyasu S, Yamashita N, et al. 2004. Perfluorinated compounds in coastal waters of Hong Kong, South China, and Korea[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 38(15): 4056–4063. |

| Sun H W, Li F S, Zhang T, et al. 2011. Perfluorinated compounds in surface waters and WWTPs in Shenyang, China:mass flows and source analysis[J]. Water Research, 45(15): 4483–4490.DOI:10.1016/j.watres.2011.05.036 |

| Sun H W, Zhang X Z, Wang L, et al. 2012. Perfluoroalkyl compounds in municipal WWTPs in Tianjin, Chinadconcentrations, distribution and mass flow[J]. Environmental Science & Pollution Research International, 19(5): 1405–1415. |

| Wang T, Khim J S, Chen C, et al. 2012. Perfluorinated compounds in surface waters from Northern China:comparison to level of industrialization[J]. Environment International, 42(1): 37–46. |

| 王鑫璇, 张鸿, 何龙, 等. 2014. 深圳水库群表层水中全氟化合物的分布特征[J]. 环境科学, 2014, 35(6): 2085–2090. |

| Wang S L, Wang H, Zhao W, et al. 2015. Investigation on the distribution and fate of perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) and perfluorooctanoate (PFOA) in a sewage-impacted bay[J]. Environmental Pollution, 205: 186–198.DOI:10.1016/j.envpol.2015.05.042 |

| Xu L, Krenitsky D M, Seacat A M, et al. 2004. Biotransformation of N-Ethyl-N-(2-hydroxyethyl) perfluorooctanesulfonamide by rat liver microsomes, cytosol, and slices and by expressed rat and human cytochromes P450[J]. Chemical Research in Toxicology, 17(6): 767–775.DOI:10.1021/tx034222x |

| 姚义鸣, 赵洋洋, 孙红文. 2016. 天津市大气中全氟化合物挥发性前体物的分布和季节变化[J]. 环境化学, 2016, 35(7): 1329–1336.DOI:10.7524/j.issn.0254-6108.2016.07.2015120903 |

| Ye F, Tokumura M, Islam M S, et al. 2014. Spatial distribution and importance of potential perfluoroalkyl acid precursors in urban rivers and sewage treatment plant effluent-Case study of Tama River, Japan[J]. Water Research, 67: 77–85.DOI:10.1016/j.watres.2014.09.014 |

| Ye F, Zushi Y, Masunaga S. 2015. Survey of perfluoroalkyl acids (PFAAs) and their precursors present in Japanese consumer products[J]. Chemosphere, 127(5): 262–268. |

| 张大文, 王冬根, 张莉, 等. 2012. 太湖梅梁湾全氟化合物污染现状研究[J]. 环境科学学报, 2012, 32(12): 2978–2985. |

| Zhang Y Y, Lai S C, Zhao Z, et al. 2013. Spatial distribution of perfluoroalkyl acids in the Pearl River of Southern China[J]. Chemosphere, 93(8): 1519–1525.DOI:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2013.07.060 |

| Zushi Y, Ye F, Motegi M, et al. 2011. Spatially detailed survey on pollution by multiple perfluorinated compounds in the Tokyo Bay basin of Japan[J]. Environmental Science & Technology, 45(7): 2887–2893. |