,1, 李婷1, 王燕1, 陈卓1, 马义诚1, 任强林1, 刘佳佳2, 杨会国2, 姚刚

,1, 李婷1, 王燕1, 陈卓1, 马义诚1, 任强林1, 刘佳佳2, 杨会国2, 姚刚 ,1

,1Comparison of Growth Physiology and Gut Microbiota Between Healthy and Diarrheic Lambs in Pre- and Post-Weaning Period

YANG NingZhi ,1, LI Ting1, WANG Yan1, CHEN Zhuo1, MA YiCheng1, REN QiangLin1, LIU JiaJia2, YANG HuiGuo2, YAO Gang

,1, LI Ting1, WANG Yan1, CHEN Zhuo1, MA YiCheng1, REN QiangLin1, LIU JiaJia2, YANG HuiGuo2, YAO Gang ,1

,1通讯作者:

责任编辑: 林鉴非

收稿日期:2020-03-8接受日期:2020-07-10网络出版日期:2021-01-16

| 基金资助: |

Received:2020-03-8Accepted:2020-07-10Online:2021-01-16

作者简介 About authors

杨柠芝,E-mail:

摘要

关键词:

Abstract

Keywords:

PDF (2679KB)元数据多维度评价相关文章导出EndNote|Ris|Bibtex收藏本文

本文引用格式

杨柠芝, 李婷, 王燕, 陈卓, 马义诚, 任强林, 刘佳佳, 杨会国, 姚刚. 断奶前后非特异病原性腹泻羔羊生长生理及肠道菌群差异性比较[J]. 中国农业科学, 2021, 54(2): 422-434 doi:10.3864/j.issn.0578-1752.2021.02.017

YANG NingZhi, LI Ting, WANG Yan, CHEN Zhuo, MA YiCheng, REN QiangLin, LIU JiaJia, YANG HuiGuo, YAO Gang.

开放科学(资源服务)标识码(OSID):

0 引言

【研究意义】断奶是羔羊、犊牛等哺乳动物幼畜生长发育的关键时期之一。断奶时哺乳动物幼畜从以吸吮富含营养且易消化的母乳为主转向以采食固体饲料为主,其消化道形态功能发生剧烈变化。断奶期羔羊在饲料营养结构改变、环境应激、病原入侵等因素的综合影响下,羔羊极易发生以腹泻为特征的消化道疾病,导致其生长迟滞甚至死亡,造成羔羊生产效率低下以及巨大的经济损失[1,2,3]。羔羊断奶期的消化系统形态结构和功能的生长发育变化以及致羔羊腹泻的多病因学研究报道已屡见不鲜[4,5,6,7]。导致羔羊腹泻的原因也会随年龄的变化而变化[8,9]。由于断奶过程带来的羔羊生存环境的巨大变化,断奶期健康羔羊的肠道菌群也会发生显著变化,断奶前和断奶后肠道菌群的组成结构也具有显著差异性[10,11]。因此,揭示断奶期腹泻羔羊宿主生理生化变化和肠道菌群的变化特点对于精准防治羔羊消化道疾病,减少发病率和死亡率,提高羔羊生产效益具有重要科学意义。【前人研究进展】近年来,肠道菌群在宿主健康调控中的作用日益凸显,婴幼儿和幼畜发生腹泻和肠道菌群的改变关系密切。在猪流行性腹泻病毒(PEDV)感染的吮乳仔猪肠道中,整体微生态平衡被打破,表现为梭杆菌门(Fusobacterium)、变形菌门(Proteobacteria)相对丰度显著高于健康仔猪,而拟杆菌门(Bacteroidetes)丰度显著低于健康仔猪[12]。HUANG等[13]发现断奶过渡期因PEDV感染发生腹泻的吮乳仔猪大肠埃希氏菌(Escherichia-Shigella)、肠球菌(Enterococcus)、梭菌(Fusobacterium)和韦荣球菌(Veillonella)菌属显著高于健康对照组仔猪。人和动物的腹泻是多种胃肠道疾病以及非肠道感染的其他疾病的主要临床表现,大多具有炎性症状发生和机体免疫异常[14,15],在炎症肠病发生发展过程中,细胞因子起着重要的作用,主要表现为促炎和抗炎细胞因子之间相互促进相互制约作用,二者的动态变化决定了炎症的发展及结局[16]。Fernández等比较了断奶前健康与腹泻羔羊的血清细胞因子的变化,发现腹泻羔羊的IL-1β浓度极显著高于健康对照组[17]。因球虫感染导致的腹泻羔羊肠道免疫组化结果显示所检测的细胞因子IFN-α、IFN-γ、IL-1α、IL-1β、IL-2、IL-6、IL-10、TNF-α和TNF-β均显著高于健康对照组羔羊,其中增高最多的是促炎细胞因子IL-1α和IL-6[18]。发生轮状病毒性腹泻的(20月龄内)婴幼儿的IL-6、IL-10和IFN-γ也显著高于健康对照组[19]。杨立华等[20]研究发现无论是病毒感染还是细菌感染,腹泻患儿的血清细胞因子TNF-α、IL-6、IL-8均显著升高。与健康羔羊相比,目前对于断奶前和断奶后腹泻羔羊生理状况和其肠道菌群的差异性变化以及宿主和其肠道菌群的互作关系尚缺乏足够清晰的比较研究。【本研究切入点】针对断奶前和断奶后临床散发、非传染性腹泻的羔羊,即非特异病原性腹泻羔羊,采用与其对应日龄段的健康羔羊进行比较的方法,排除日龄变化的叠加干扰,比较断奶前和断奶后腹泻羔羊生长、生理生化指标、炎性因子和肠道菌群组成结构变化。【拟解决的关键问题】探索断奶前、后腹泻羔羊的上述变化的差异性。以期为不同生长阶段羔羊腹泻的精准防治奠定基础。1 材料与方法

1.1 试验设计与动物分组

本试验在新疆木垒县某湖羊养殖场进行,试验时间为2017年5—12月。该场羔羊随母羊吮乳,在10—15日龄起开始补饲开食料。当吮乳羔羊日龄在45 d左右、体重达15±2 kg左右开始断奶,断奶后羔羊完全采食固体饲料。围绕羔羊断奶时期对临床散发、无特异病原的非传染性腹泻羔羊进行临床调查,统计腹泻和死亡羔羊,计算腹泻率、死亡率等指标。在此基础上,随机选择断奶前(31—45日龄)健康和腹泻羔羊各10只,断奶后(60—75日龄)健康和腹泻羔羊各10只进行采样和各项指标测定。健康羔羊与腹泻羔羊样品均在采食前采集,所有羔羊采样前无任何抗生素接触史。羔羊分组及日粮组成见表1、2。Table 1

表1

表1试验分组

Table 1

| 分组 Grouping | 日龄(天) Age(d) | 健康组 Health group | 腹泻组 Diarrhea group |

|---|---|---|---|

| 断奶前(Suckling) | 31-45 | H组(Health) | D组(Diarrhea) |

| 断奶后(Weaned) | 60-75 | h组(health) | d组(diarrhea) |

新窗口打开|下载CSV

Table 2

表2

表2断奶前后羔羊日粮组成及营养水平

Table 2

| 原料 Ingredient | 日粮组成 Diet composition (%) | 营养成分 Nutritional components | 营养水平 Nutrient levels | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 断奶前Suckling | 断奶后Weaned | 断奶前Suckling | 断奶后Weaned | ||

| 玉米Corn | 43.12 | 25.20 | 干物质 DM (%) | 82.29 | 86.65 |

| 麸皮Wheat bran | 3.75 | 4.40 | 消化能DE (MJ·kg-1) | 10.41 | 6.43 |

| 豆粕Sybean meal | 16.50 | 4.40 | 粗蛋白 CP (%) | 16.76 | 10.76 |

| 棉粕Cottonseed meal | 3.00 | 1.20 | 粗纤维 CF (%) | 11.01 | 24.48 |

| 葵粕Sunflower meal | 2.63 | 2.00 | 粗灰分Ash (%) | 4.43 | 6.27 |

| 酵母Brewers dried yeast | 0.70 | 1.60 | 钙 Ca (%) | 0.57 | 0.51 |

| 食盐NaCl | 0.80 | 0.40 | 总磷 P (%) | 0.34 | 0.23 |

| 石粉Limestone | 0.80 | 0.40 | |||

| 碳酸氢钠Sodium bicarbonate | 3.70 | 0.40 | |||

| 麦秸Wheat straw | 10.00 | 40.00 | |||

| 苜蓿草粉Alfalfa meal | 14.00 | 19.00 | |||

| 复合预混料Premix | 1.00 | 1.00 | |||

| 合计Total | 100.00 | 100.00 | |||

新窗口打开|下载CSV

1.2 临床观察测定与样品采集

1.2.1 羔羊腹泻观察测定 每天11:00和17:00在羔羊采食前分别观察羔羊粪便,出现腹泻症状即采样,参考MARQUARDT等[21]的方法进行粪便形态评分。即,0分:正常,粪便条形或粒状;1分:软粪、成形;2分:轻腹泻,不成形、粪水未分离;3分:严重腹泻,液状、不成形、粪水分离(图1)。当粪便评分为2分或以上时认为羔羊发生腹泻并统计腹泻只数及次数。计算腹泻率=试验期内每组羔羊腹泻头次/(试验天数×每组羔羊头数)×100%和腹泻病死率=死亡羔羊数/腹泻羔羊数×100%。图1

新窗口打开|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT

新窗口打开|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT图1粪便形态评分(从左至右:0、1、2和3四级)

Fig. 1Fecal consistency score(left-right:score of 0, 1, 2, 3 and 4)

1.2.2 样品采集 经羔羊颈静脉采集全血和抗凝血各5 mL,全血静置析出血清后,再经离心分离血清,置于-80 ℃保存。后期用于血液生化指标及炎症因子测定。抗凝血(肝素钠)用于血液生理指标测定。经肛门采集直肠粪样后迅速液氮保存,用于进行16S rRNA测序,分析菌群结构变化。

1.3 指标测定

1.3.1 体重测定 测定时间为早晨08:00空腹称重。1.3.2 体温、脉搏和呼吸(TPR)测定 每天17:00测定。观察安静状态下羔羊单位时间呼吸次数,固定羔羊采用温度计测定肛温。最后触压颈静脉测定脉搏。

1.3.3 血液生理、生化指标测定 生理指标采用XFA6030全自动动物血液细胞分析仪测定;生化指标用TDEXX VetTest生化分析仪测定;

1.3.4 炎症因子检测 采用双抗夹心ELISA试剂盒(武汉基因美生物技术有限公司)测定4种炎症因子:IL-1β(JYM0025Sh)、IL-6(JYM0011Sh)、IL-10(JYM0026Sh)和IL-18(JYM0066Sh)。

1.3.5 肠道群落结构多样性测定 采用粪便基因组 DNA 提取试剂盒(天根生化有限公司)。完成基因组抽提后用分光光度计测定其浓度和纯度,琼脂凝胶电泳试验检测提取 DNA 的质量。之后进行目标片段 PCR 扩增,2%琼脂糖凝胶电泳试验对扩增产物进行检测,之后回收目的片段,使用 AXYGEN公司的凝胶回收试剂盒。参照电泳初步定量结果,将 PCR 扩增回收产物进行荧光定量。采用 Illumina 公司的 TruSeq Nano DNA LT Libray Prep Kit 制备测序文库。采用Agilent High Sensitivity DNA Kit对文库在 Agilent Bioanalyzer上进行上机前质检,质检合格后采用 Quant-iT Pico Green dsDNA Assay Kit 在 Promega QuantiFluo 荧光定量系统上对文库进行定量。定量结果根据所需测序量按一定的比例进行混合,并经NaOH变性后进行上机测序;使用 MiSeq 测序仪进行 2×300 bp 的双端测序,相应试剂为 MiSeqReagent Kit V3 (600 cycles)。测序长度为 200—450 bp。选取粪便样品中的菌群 16S rRNA的 V3 和 V4 可变区域进行高通量测序和分析。

1.4 数据处理

采用软件 Trimmomatic、FLASH、Usearch、perl 程序对测序得到的 PE reads 根据overlap 关系进行拼接,同时对序列质量进行质控和过滤,区分样本后用软件平台 Usearch对 OTU 聚类分析和物种分类学的分析,基于OTU用 mothur 进行Alpha多样性分析。试验结果数据以Mean±SE表示。采用SPSS 22.0统计软件对数据进行独立样本T检验。P<0.05作为差异显著的判断标准。2 结果

2.1 断奶前后健康与腹泻羔羊的生长生理比较

2.1.1 断奶前后健康与腹泻羔羊腹泻率与死亡率 对出生后0—75日龄共461只羔羊分段进行临床散发的腹泻羔羊腹泻只(次)数观察记录,发现腹泻羔羊179只(次),总腹泻率为2.59%,总腹泻病死率为29.6%。其中,断奶前31—45日龄阶段腹泻率为2.49%,病死率为40.9%,断奶后60—75日龄阶段腹泻率为2.27%,病死率为20.6%。各日龄阶段腹泻及死亡羔羊情况见表3所示。Table 3

表3

表3断奶前后羔羊腹泻率与病死亡率统计

Table 3

| 日龄 Age (d) | 总头数 N. lambs | 腹泻只(次)数 N. diarrhea | 腹泻率 Diarrhea rate | 死亡数 N. death | 病死率 Mortality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-15 | 80 | 34 | 2.83 | 18 | 52.90 |

| 16-30 | 122 | 55 | 3.01 | 12 | 21.80 |

| 31-45 | 59 | 22 | 2.49 | 9 | 40.90 |

| 60-75 | 200 | 68 | 2.27 | 14 | 20.60 |

| 总计Total | 461 | 179 | 2.59 | 53 | 29.60 |

新窗口打开|下载CSV

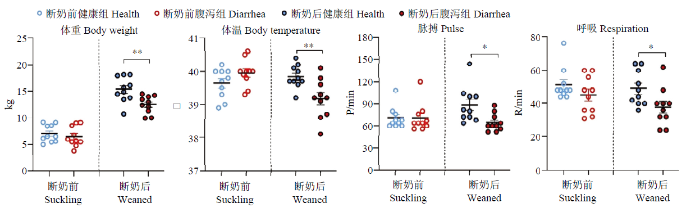

2.1.2 羔羊体重与生理指标 断奶前健康与腹泻羔羊体重差异不显著(P>0.05)。而断奶后腹泻羔羊体重极显著低于健康羔羊(P<0.01),且腹泻羔羊的体温极显著低于健康羔羊(P<0.01),脉搏和呼吸频率也均显著低于健康羔羊(P<0.05,表4)。

Table 4

表4

表4断奶前后健康与腹泻羔羊血液生理指标

Table 4

| 指标 Index | 断奶前Suckling | 断奶后Weaned | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 健康Health | 腹泻Diarrhea | 健康Health | 腹泻Diarrhea | |

| 白细胞WBC | 8.69±0.39 | 9.12±0.45 | 8.96±0.36A | 11.20±0.47B |

| 淋巴细胞LY | 4.42±0.32 | 5.00±0.26 | 5.84±0.34 | 6.23±0.42 |

| 中性粒细胞Gran | 4.14±0.46 | 4.33±0.85 | 5.36±0.87 | 5.29±0.72 |

| 血红蛋白HGB | 107.00±3.78 | 108.00±5.16 | 127.00±4.44 | 141.00±5.06 |

| 红细胞RBC | 9.43±0.24 | 8.97±0.43 | 8.69±0.24 | 9.30±0.34 |

| 血小板PLT | 507.00±38.9 | 487.00±38.40 | 750.00±40.00 | 768.00±55.00 |

新窗口打开|下载CSV

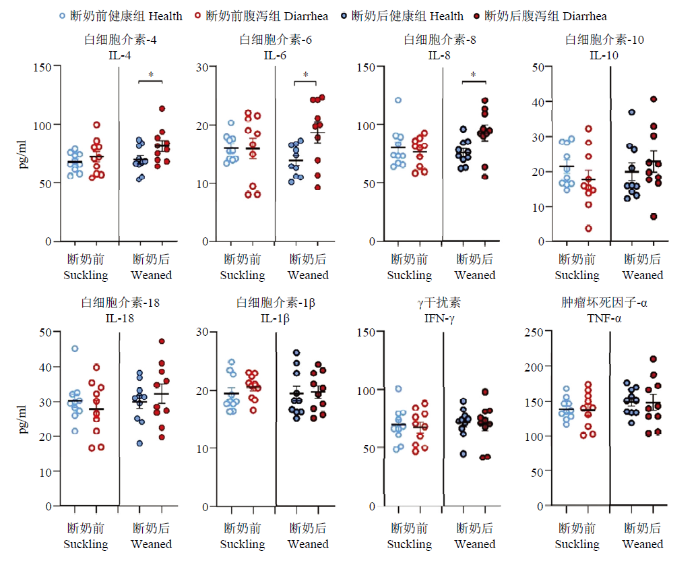

2.1.3 羔羊血液生理生化指标及炎性因子 断奶后腹泻羔羊白细胞总数极显著高于健康羔羊(P<0.01),其他血液生理指标各组间均无显著差异(P>0.05,表5)。断奶前腹泻羔羊的总蛋白、球蛋白、胆固醇、磷均显著低于健康羔羊(P<0.05);而断奶后腹泻羔羊血中尿素氮、肌酐和磷均极显著低于健康羔羊(P<0.01),血糖和总胆红素显著低于健康羔羊(P<0.05)。其他指标各组间无显著差异(P>0.05,表6)。如图3所示,断奶前健康和腹泻羔羊之间炎症相关因子均无显著差异(P>0.05),而断奶后腹泻羔羊IL-4、IL-6和IL-8显著高于健康羔羊(P<0.05)。

Table 5

表5

表5断奶前后健康与腹泻羔羊血液生化指标比较

Table 5

| 指标 Index | 断奶前Suckling | 断奶后Weaned | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 健康Health | 腹泻Diarrhea | 健康health | 腹泻diarrhea | |

| 碱性磷酸酶ALKP(U·L-1) | 355.00±90.30 | 169.20±73.13 | 38.80±9.20 | 69.80±38.27 |

| 丙氨酸转移酶ALT(U·L-1) | 186.40±152.42 | 228.00±258.80 | 37.20±16.77 | 37.40±18.77 |

| 胰淀粉酶AMYL(U·L-1) | 64.60±12.88 | 59.20±34.78 | 32.00±30.54 | 54.80±30.26 |

| 白蛋白ALB(g·L-1) | 19.00±2.35 | 19.60±1.82 | 15.20±5.72 | 19.80±6.61 |

| 球蛋白GLOB(g·L-1) | 48.80±3.97a | 35.60±5.35b | 56.80±12.48 | 47.40±14.08 |

| 总蛋白TP(g·L-1) | 66.40±15.79a | 55.00±5.24b | 72.00±9.05 | 67.20±9.41 |

| 胆固醇CHOL(mmol·L-1) | 3.70±1.87a | 2.52±0.86b | 0.58±0.34 | 0.77±0.22 |

| 肌酐CREA(mmol·L-1) | 39.00±14.07 | 27.20±5.72 | 35.80±7.60A | 22.90±5.60B |

| 尿素氮UREA(mmol·L-1) | 4.18±1.45 | 3.64±1.28 | 9.15±2.50A | 6.48±0.94B |

| 总胆红素BIL(mmol·L-1) | 2.80±1.64 | 2.00±2.23 | 4.00±2.94a | 1.20±0.44b |

| 血糖GLU(mmol·L-1) | 5.36±0.71 | 5.42±1.72 | 4.85±1.01a | 3.93±0.64b |

| 钙离子Ca(mmol·L-1) | 2.50±0.08 | 2.35±0.20 | 2.14±0.27 | 2.11±0.10 |

| 磷PHOS(mmol·L-1) | 2.89±0.82a | 2.18±0.40b | 2.52±0.58A | 1.64±0.31B |

新窗口打开|下载CSV

Table 6

表6

表6健康和腹泻羔羊肠道菌群差异显著性检验

Table 6

| 方法 Method name | P | 断奶前 Suckling | 断奶后 Weaned | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 加权UniFrac Weighted UniFrac | Adonis | Pr (>F) | 0.02 | 0.26 |

| Anosim | P-value | 0.04 | 0.15 | |

新窗口打开|下载CSV

图2

新窗口打开|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT

新窗口打开|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT图2断奶前后健康与腹泻羔羊体重及体温、脉搏和呼吸参数

Fig. 2Body weight, temperature, pulse and respiratory parameters of healthy and diarrheic lambs in pre- and poster- weaning time

图3

新窗口打开|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT

新窗口打开|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT图3断奶前后健康与腹泻羔羊炎症因子变化

Fig. 3Changes of inflammatory factors of healthy and diarrheic lambs in pre- and poster- weaning time

2.2 断奶前后健康与腹泻羔羊的肠道菌群结构比较

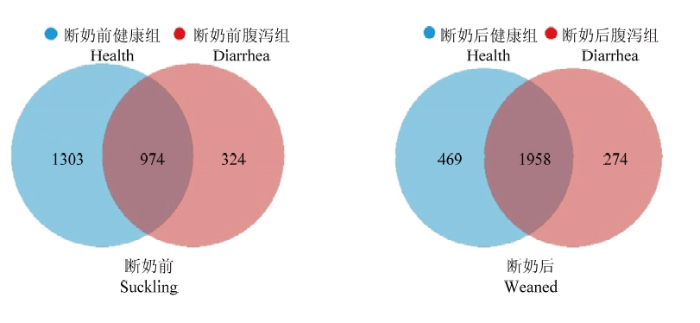

2.2.1 羔羊共有OTU 断奶前健康羔羊特有OTUs占比50.10%,腹泻羔羊特有OTUs占比12.46%,共有OTUs占比为37.45%。而断奶后健康羔羊特有OTUs占比17.36%,腹泻羔羊特有OTUs占比为10.14%,共有OTUs占比72.49%(图4)。断奶后健康组与腹泻羔羊共有OTUs占比(72.49%)较断奶前健康组与腹泻羔羊共有OTUs占比(37.45%)升高近一倍。图4

新窗口打开|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT

新窗口打开|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT图4断奶前后健康和腹泻羔羊肠道菌群OTUs Venn分析

Fig. 4Venn analysis of OTUs of gut microbiota of healthy and diarrheic lambs in pre- and poster- weaning time

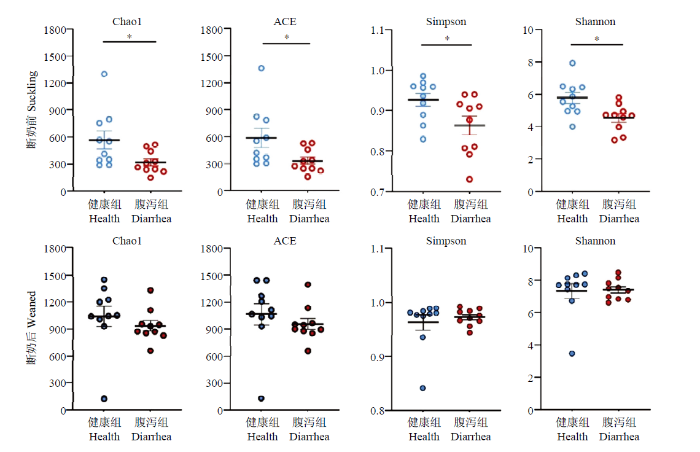

2.2.2 Alpha多样性分析 Alpha多样性指数(图5)表明,断奶前健康组与腹泻组羔羊肠道菌群Alpha多样性指数均差异显著,健康组显著高于腹泻组(P<0.05)。而断奶后健康组与腹泻羔羊肠道菌群Alpha多样性均无组间差异(P>0.05)。

图5

新窗口打开|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT

新窗口打开|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT图5断奶前后健康与腹泻羔羊肠道菌群 Alpha多样性指数

Fig. 5Alpha-diversity index of the gut microbiota of healthy and diarrheic lambs in pre- and poster- weaning time

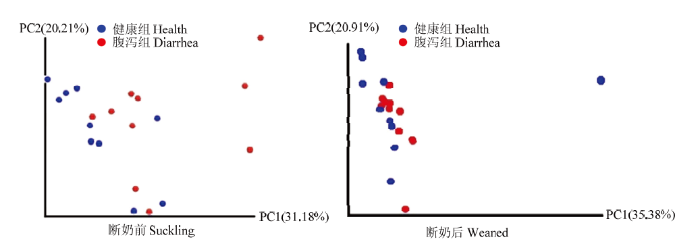

2.2.3 Beta多样性分析 断奶前健康和腹泻羔羊肠道菌群Beta多样性PCA比较,PC1贡献率占31.18%,PC2贡献率占20.21%,健康与腹泻组间Weighted Unifrac Adonis和Anosim检验均达显著水平(P<0.05,图6);而断奶后健康与腹泻羔羊肠道菌群β多样性PCA比较,PC1的贡献率占35.38%,PC2的贡献率占20.91%。健康与腹泻组间Adonis和Anosim检验差异不显著(P>0.05)

图6

新窗口打开|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT

新窗口打开|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT图6断奶前后健康与腹泻羔羊肠道菌群Weighted UniFrac PCA

Fig. 6Weighted UniFrac PCA of gut microbiota of healthy and diarrheic lambs in pre- and poster- weaning time

2.3 断奶前后健康与腹泻羔羊肠道菌群差异比较

断奶前、后健康与腹泻羔羊肠道菌群类群数如表7,断奶前腹泻羔羊属水平和种水平类群数显著少于健康羔羊(P<0.05),而断奶后两组间各分类水平无组间差异(P>0.05)。Table 7

表7

表7健康和腹泻羔羊肠道菌群各分类水平类群数

Table 7

| 分类水平 Classification level | 断奶前 Suckling | 断奶后 Weaned | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 健康 Health | 腹泻 Diarrhea | 健康 Health | 腹泻 Diarrhea | |

| 门Phylum | 8.70±1.25 | 8.00±2.67 | 10.70±2.50 | 11.30±1.59 |

| 纲Class | 16.00±2.70 | 14.00±3.68 | 20.80±3.67 | 20.40±2.11 |

| 目Order | 20.10±4.30 | 16.00±4.97 | 27.00±5.56 | 27.10±4.04 |

| 科Family | 35.3±7.13 | 28.80±7.91 | 45.90±9.37 | 46.30±5.53 |

| 属Genus | 56.1±9.75a | 46.40±12.07b | 67.70±13.33 | 67.80±8.53 |

| 种Species | 63.3±9.25a | 52.70±12.27b | 69.30±13.49 | 70.10±9.27 |

新窗口打开|下载CSV

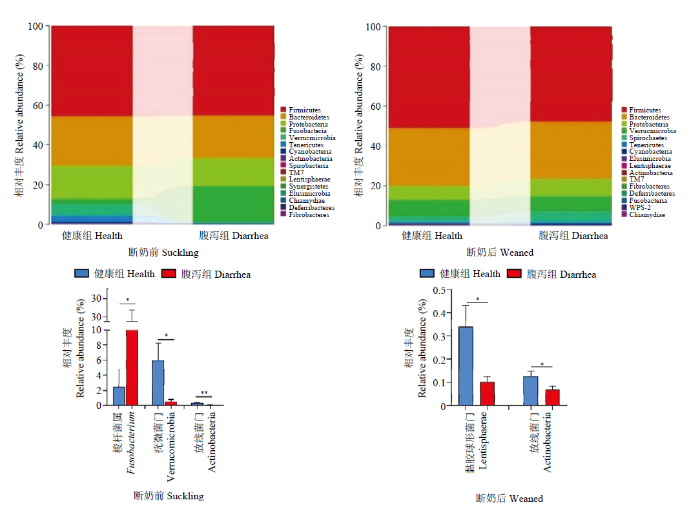

2.3.1 门水平 如图7所示,断奶前健康与腹泻羔羊肠道菌群梭杆菌门(Fusobacteria),疣微菌门(Verrucomicrobia)和放线菌门(Actinobacteria)相对丰度存在显著组间差异,其中,健康羔羊梭杆菌门(Fusobacteria)显著低于腹泻羔羊,而疣微菌门(Verrucomicrobia)和放线菌门(Actinobacteria)显著高于腹泻羔羊(P<0.05)。而断奶后健康羔羊的黏胶球形菌门(Lentisphaerae)和放线菌门(Actinobacteria)相对丰度显著高于腹泻组(P<0.05)。

图7

新窗口打开|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT

新窗口打开|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT图7健康和腹泻羔羊肠道菌群门水平相对丰度及差异菌群

Fig. 7Relative abundance and difference of gut microbiota of healthy and diarrheic lambs in pre- and poster- weaning time at phyla level

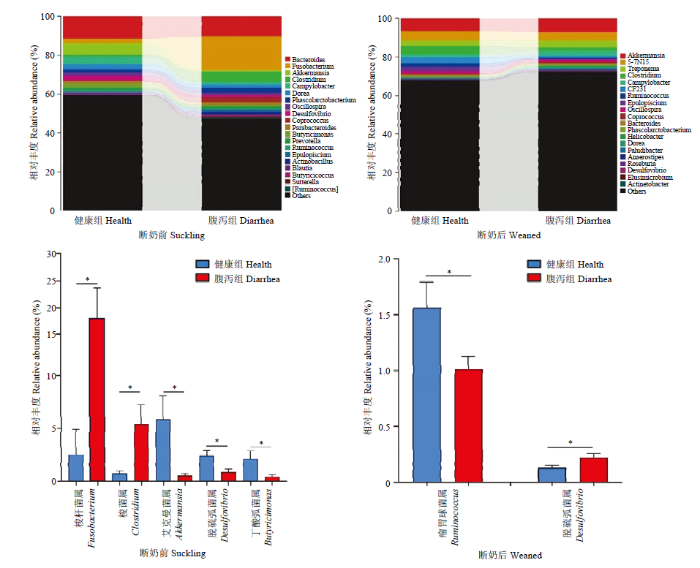

2.3.2 属水平 如图8所示,断奶前健康与腹泻羔羊肠道菌群在梭杆菌属(Fusobacterium)、梭菌属(Clostridium)、艾克曼菌属(Akkermansia)、脱硫弧菌属(Desulfovibrio)和丁酸弧菌属(Butyricimonas)等5个菌属的相对丰度存在显著组间差异(P<0.05),其中,健康羔羊的梭杆菌属(Fusobacterium)和梭菌属(Clostridium)显著低于腹泻羔羊,而艾克曼菌属(Akkermansia)、脱硫弧菌属(Desulfovibrio)和丁酸弧菌属(Butyricimonas)显著高于腹泻羔羊;断奶后健康和腹泻羔羊瘤胃球菌属(Ruminococcus)和脱硫弧菌属(Desulfovibrio)存在显著组间差异(P<0.05),其中前者在健康羔羊显著高于腹泻组,而后者显著低于腹泻羔羊。

图8

新窗口打开|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT

新窗口打开|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT图8健康和腹泻羔羊肠道菌群属水平相对丰度及差异菌群

Fig. 8Relative abundance and difference of gut microbiota of healthy and diarrheic lambs in pre- and poster- weaning time at genera level

3 讨论

3.1 生理生化指标变化

本试验发现,在断奶前阶段,健康组和腹泻羔羊的体重、体温、脉搏和呼吸频率(TPR)均无显著差异;而断奶后腹泻羔羊的体重和TPR均显著低于健康羔羊。在早期断奶羔羊和断奶后仔猪研究中,均出现腹泻羔羊和仔猪体重下降的研究报道[8-11,22]。本试验发现断奶前腹泻羔羊的血清总蛋白、球蛋白、总胆固醇显著低于健康组,其他血液生理生化指标两组间无显著差异。而断奶后腹泻羔羊白细胞显著高于健康羔羊,且腹泻羔羊的血清尿素氮和肌酐极显著低于健康组,血糖和总胆红素也显著低于健康羔羊。唯有血磷浓度无论是断奶前还是断奶后,均为腹泻组显著低于健康组。在感染球虫发生腹泻的断奶羔羊中也发现WBC显著高于健康对照组[23],磷浓度显著低于健康对照组[7]。蒋莉等人在研究儿童慢性腹泻合并肠道蛋白丢失的试验中发现患儿的总蛋白和球蛋白浓度均显著低于健康对照组[24]。SALEM等[25]在细小病毒感染的腹泻幼犬血清检测到总蛋白和白蛋白下降的结果,与本试验结果一致,而甘油三酯和血清尿素氮显著高于健康幼犬的结果与本结果不一致。这些差异可能是由于不同动物,不同年龄段或是不同腹泻原因所致。本试验结果显示断奶前腹泻羔羊主要发生以蛋白质和血脂降低为主的变化,而断奶后腹泻羔羊则发生尿素氮、肌酐和血糖等指标的下降变化,此变化可能与断奶造成日粮改变有关。3.2 细胞因子变化

本试验针对断奶前和断奶后两个阶段的健康和腹泻羔羊血清炎性相关细胞因子IL-4、IL-6、IL-8、IL-10、IL-18以及IL-1β、IFN-γ和TNF-α进行了比较,发现断奶前健康和腹泻羔羊之间各细胞因子均无显著差异。而断奶后腹泻羔羊的IL-4、IL-6和IL-8显著高于健康羔羊。KUMAR等[26]在羔羊感染副结核分枝杆菌导致腹泻的研究中发现羔羊的IL-4显著高于健康对照组。但FERNANDEZ等[17]在检测11—18日龄吮乳期健康与腹泻羔羊的细胞因子时发现腹泻羔羊的血清IL-1β显著高于健康对照组羔羊。SAKAI等[27]采用氟脲嘧啶5诱导发生腹泻的小鼠试验中,也发现腹泻小鼠不同段肠道的TNF-α、IL-1β、IL-6、IFN γ 、IL-17和 IL-22 的mRNA水平均显著升高。JIANG等[19]发现患轮状病毒腹泻儿童的IL-6、IL-10和IFN-γ显著高于健康对照组儿童。腹泻疾病过程中的细胞因子变化是由于促炎和抗炎因子的复杂动态平衡与互作[28]。本试验和其他研究在不同动物、不同诱因导致的腹泻研究中均检测到血清IL-6和/或其mRNA表达水平的升高,鉴于IL-6在炎症反应中的促炎/抗炎双向生物学作用,提示IL-6可能在羔羊腹泻过程中维持机体免疫稳态具有特殊重要作用[29,30]。3.3 肠道菌群变化

断奶期的日粮改变是引起哺乳动物肠道菌群组成结构发生剧烈变化的主要环境因素[31,32,33]。本研究发现,断奶后健康与腹泻羔羊共有OTUs占比(72.49%)较断奶前健康与腹泻羔羊共有OTUs占比(37.45%)升高近一倍。断奶前腹泻羔羊菌群Alpha多样性各项指数均显著低于健康羔羊,而断奶后羔羊未呈现显著的组间差异。Beta多样性(PCA)结果显示断奶前健康与腹泻组呈现显著差异分布,断奶后健康与腹泻羔羊肠道菌群分布差异不显著。NAKAMURA等[34]在研究11日龄左右健康日本黑牛吮乳期健康犊牛和腹泻犊牛粪菌组成结构时发现,后者的粪菌群Alpha多样性指标均显著低于健康组。健康组和腹泻组无论是瘤胃菌群还是粪菌群的Beta多样性的相似程度都较低。与本研究健康和腹泻羔羊粪菌群的组成结构结果基本一致。SAKAITANI等[35]研究表明,动物肠道菌群会随着年龄的增加和饮食习惯的改变而逐渐发生变化。THOMPSON等[36]研究发现。3—36日龄仔猪粪便菌群多样性随着日龄的变化而呈现升高趋势,直到仔猪断奶后粪便菌群多样性才基本趋于稳定。因此,本试验中断奶前健康与腹泻羔羊肠道菌群多样性均呈现出显著差异,而断奶后健康与腹泻羔羊肠道菌群多样性则无显著性差异,可能断奶后羔羊肠道菌群多样性已基本处于相对稳态,腹泻对其影响程度较低。本研究发现,断奶前腹泻羔羊的梭杆菌门(Fusobacteria)相对丰度显著高于健康羔羊,而疣微菌门(Verrucomicrobia)和放线菌门(Actinobacteria)显著低于健康羔羊。属水平差异为:腹泻羔羊的梭杆菌属(Fusobacterium)和梭菌属(Clostridium)均显著高于健康羔羊,而艾克曼菌属(Akkermansia)、脱硫弧菌属(Desulfovibrio)和丁酸弧菌属(Butyricimonas)显著低于健康羔羊。而断奶后,腹泻羔羊低丰度的黏胶球形菌门(Lentisphaerae)和放线菌门(Actinobacteria)相对丰度显著低于健康羔羊。而腹泻羔羊的瘤胃球菌属(Ruminococcus)显著低于健康羔羊;脱硫弧菌属(Desulfovibrio)则显著高于健康羔羊。与断奶前相比,断奶后腹泻羔羊肠道菌群呈现不同的肠道菌群变化谱。梭杆菌属是革兰氏阴性无芽孢专性厌氧杆菌属,含有多种与消化道炎性疾病发生密切相关的致病菌[37]。梭菌属是革兰氏阳性梭状芽孢杆菌属,该属中主要的致病性厌氧芽孢梭菌可引起人和动物的破伤风、气性坏疽、坏死性肠炎、食物中毒以及艰难梭菌性肠炎等疾病[38]。TAN等[39]在比较感染流行性腹泻的吮乳仔猪和健康仔猪结肠组成时发现梭杆菌门(Fusobacteria)和梭杆菌属(Fusobacterium)菌群均显著高于健康仔猪。脱硫弧菌属(Desulfovibrio)、丁酸弧菌属(Butyricimonas),均为反刍动物瘤胃中的共生革兰氏阴性厌氧菌。前者的一些致病菌可引起以慢性腹泻为临床特征之一的增殖性肠病[40,41],后者可引起菌血症等感染性疾病[42,43]。疣微菌门(Verrucomicrobia)属于PVC超级菌门(superphylum:Planctomycetes,Verrucomicrobia,Chlamydia)家族成员之一,艾克曼菌属(Akkermansia)是疣微菌门(Verrucomicrobia)在肠道中发现的重要菌属,该菌属中的A. muciniphila具有黏液降解作用,对于维持肠黏膜完整性具有重要作用[44]。ZHAO等[45]用A. muciniphila饲喂小鼠,研究前者和小鼠炎性变化的关系。结果显示日粮添加A. muciniphila可显著改善小鼠的炎症状态。本研究发现断奶前后腹泻羔羊呈现出不同的肠道菌群变化特点,断奶前腹泻羔羊的肠道菌群失调变化较断奶后明显。但由于本试验主要针对临床散发的非特异病原性腹泻症状为主进行了肠道菌群的比较研究,未对特异病原进行检测。因此,导致断奶前后腹泻羔羊肠道菌群差异性的原因与机理尚需进一步探索。

4 结论

断奶前腹泻羔羊的生长状况、生理生化及炎性反应变化以及肠道菌群组成结构变化与断奶后腹泻羔羊的变化具有显著的差异性。断奶前腹泻羔羊主要表现以蛋白质和血脂降低为主;而断奶后腹泻羔羊以尿素氮、肌酐和血糖指标的下降为主。断奶前腹泻羔羊肠道菌群失调变化明显;而断奶后腹泻羔羊炎症反应等变化明显。这些差异变化可能与断奶所引起的日粮组成结构和环境因素改变密切相关。其背后的菌群-宿主互作机理值得进一步研究。参考文献 原文顺序

文献年度倒序

文中引用次数倒序

被引期刊影响因子

[D].

[本文引用: 1]

[D].

[本文引用: 1]

URL [本文引用: 1]

URL [本文引用: 1]

URL [本文引用: 1]

URL [本文引用: 1]

URL [本文引用: 1]

URL [本文引用: 1]

[本文引用: 1]

[本文引用: 1]

[本文引用: 1]

[本文引用: 2]

URL [本文引用: 2]

URL [本文引用: 1]

[本文引用: 1]

URLPMID:15001189 [本文引用: 2]

DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0220829URLPMID:31365578 [本文引用: 1]

[This corrects the article DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0213144.].

DOI:10.3389/fmicb.2019.00322URLPMID:30858839 [本文引用: 1]

Porcine epidemic diarrhea (PED) is a disease that has a devastating effect on livestock. Currently, most studies are focused on comparing gut microbiota of healthy piglets and piglets with PED, resulting in gut microbial populations related to dynamic change in diarrheal piglets being poorly understood. The current study analyzed the characteristics of gut microbiota in porcine epidemic diarrhea virus (PEDV)-infected piglets during the suckling transition stage. Fresh fecal samples were collected from 1 to 3-week-old healthy piglets (n = 20) and PEDV infected piglets (n = 18) from the same swine farm. Total DNA was extracted from each sample and the V3-V4 hypervariable region of the 16S rRNA gene was amplified and sequenced using the Illumina MiSeq platform. Statistically significant differences were observed in bacterial diversity and richness between the healthy and diarrheal piglets. Principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) showed structural segregation between diseased and healthy groups, as well as among 3 different age groups. The abundance of Escherichia-Shigella, Enterococcus, Fusobacterium, and Veillonella increased due to dysbiosis induced by PEDV infection. Notably, there was a remarkable age-related increase in Fusobacterium and Veillonella in diarrheal piglets. Certain SCFA-producing bacteria, such as Ruminococcaceae_UCG-002, Butyricimonas, and Alistipes, were shared by all healthy piglets, but were not identified in various age groups of diarrheal piglets. In addition, significant differences were observed between clusters of orthologous groups (COG) functional categories of healthy and PEDV-infected piglets. Our findings demonstrated that PEDV infection caused severe perturbations in porcine gut microbiota. Therefore, regulating gut microbiota in an age-related manner may be a promising method for the prevention or treatment of PEDV.

[本文引用: 1]

[本文引用: 1]

DOI:10.1038/ncpgasthep0167URLPMID:16265204 [本文引用: 1]

Infectious diseases that do not primarily affect the gastrointestinal tract can cause severe diarrhea. The pathogenesis of this kind of diarrhea includes cytokine action, intestinal inflammation, sequestration of red blood cells, apoptosis and increased permeability of endothelial cells in the gut microvasculature, and direct invasion of gut epithelial cells by various infectious agents. Of the travel-associated systemic infections presenting with fever, diarrhea occurs in patients with malaria, dengue fever and SARS. Diarrhea also occurs in patients with community-acquired pneumonia, when it is suggestive of legionellosis. Diarrhea can also occur in patients with systemic bacterial infections. In addition, although diarrhea is rare in patients with early Lyme borreliosis, the incidence is higher in those with other tick-borne infections, such as ehrlichiosis, tick-borne relapsing fever and Rocky Mountain spotted fever. Unfortunately, it is often not established whether diarrhea is an initial symptom or develops during the course of the disease. The real incidence of diarrhea in some infectious diseases must also be questioned because it could represent an adverse reaction to antibiotics.

[本文引用: 1]

[本文引用: 1]

[本文引用: 2]

[本文引用: 1]

URLPMID:14607858 [本文引用: 2]

[本文引用: 1]

[本文引用: 1]

DOI:10.1111/fim.1999.23.issue-4URL [本文引用: 1]

URLPMID:16164007 [本文引用: 1]

[本文引用: 1]

[本文引用: 1]

URL [本文引用: 1]

[本文引用: 1]

[本文引用: 1]

URLPMID:23382968 [本文引用: 1]

[本文引用: 1]

DOI:10.1038/ni.3153URLPMID:25898198 [本文引用: 1]

Interleukin 6 (IL-6) has a broad effect on cells of the immune system and those not of the immune system and often displays hormone-like characteristics that affect homeostatic processes. IL-6 has context-dependent pro- and anti-inflammatory properties and is now regarded as a prominent target for clinical intervention. However, the signaling cassette that controls the activity of IL-6 is complicated, and distinct intervention strategies can inhibit this pathway. Clinical experience with antagonists of IL-6 has raised new questions about how and when to block this cytokine to improve disease outcome and patient wellbeing. Here we discuss the effect of IL-6 on innate and adaptive immunity and the possible advantages of various antagonists of IL-6 and consider how the immunobiology of IL-6 may inform clinical decisions.

URLPMID:20583029 [本文引用: 1]

DOI:10.1017/S1466252312000096URLPMID:22853940 [本文引用: 1]

Commensal microflora play many roles within the mammalian gastrointestinal tract (GIT) that benefit host physiology by way of direct or indirect interactions with mucosal surfaces. Commensal flora comprises members across all microbial phyla, although predominantly bacterial, with population dynamics varying with host species, genotype, and environmental factors. Little is known, however, about the complex mechanisms regulating host-commensal interactions that underlie this mutually beneficial relationship and how alterations in the microbiome may influence host development and susceptibility to infection. Research into the gut microbiome has intensified as it becomes increasingly evident that symbiont-host interactions have a significant impact on mucosal immunity and health. Furthermore, evidence that microbial populations vary significantly throughout the GIT suggest that regional differences in the microbiome may also influence immune function within distinct compartments of the GIT. Postpartum colonization of the GIT has been shown to have a direct effect on mucosal immune system development, but information is limited regarding regional effects of the microbiome on the development, activation, and maturation of the mucosal immune system. This review discusses factors influencing the colonization and establishment of the microbiome throughout the GIT of newborn calves and the evidence that regional differences in the microbiome influence mucosal immune system development and maturation. The implications of this complex interaction are also discussed in terms of possible effects on responses to enteric pathogens and vaccines.

[本文引用: 1]

DOI:10.1038/s41598-017-00223-7URLPMID:28298634 [本文引用: 1]

Ruminants microbial consortium is responsible for ruminal fermentation, a process which converts fibrous feeds unsuitable for human consumption into desirable dairy and meat products, begins to establish soon after birth. However, it undergoes a significant transition when digestion shifts from the lower intestine to ruminal fermentation. We hypothesised that delaying the transition from a high milk diet to an exclusively solid food diet (weaning) would lessen the severity of changes in the gastrointestinal microbiome during this transition. beta-diversity of ruminal and faecal microbiota shifted rapidly in early-weaned calves (6 weeks), whereas, a more gradual shift was observed in late-weaned calves (8 weeks) up to weaning. Bacteroidetes and Firmicutes were the most abundant ruminal phyla in pre- and post-weaned calves, respectively. Yet, the relative abundance of these phyla remained stable in faeces (P >/= 0.391). Inferred gene families assigned to KEGG pathways revealed an increase in ruminal carbohydrate metabolism (P

URLPMID:28992019 [本文引用: 1]

[本文引用: 1]

[本文引用: 1]

URLPMID:22067936 [本文引用: 1]

URLPMID:23320050 [本文引用: 1]

DOI:10.3390/genes11010044URL [本文引用: 1]

[本文引用: 1]

DOI:10.1128/jcm.41.6.2752-2754.2003URLPMID:12791922 [本文引用: 1]

One case of primary Desulfovibrio desulfuricans bacteremia in an immunocompetent man is presented, and 15 other reported cases are reviewed. While most isolates have not been identified to the species level, Desulfovibrio fairfieldensis and D. desulfuricans have been associated with incidents of bacteremia and D. vulgaris has been associated with intra-abdominal infections. In vitro studies suggest that empirical therapy with either imipenem or metronidazole should be considered.

URLPMID:31969420 [本文引用: 1]

URLPMID:25830028 [本文引用: 1]

[本文引用: 1]

DOI:10.1530/JME-16-0054URLPMID:27821438 [本文引用: 1]

Abnormal shifts in the composition of gut microbiota contribute to the pathogenesis of metabolic diseases, including obesity and type 2 diabetes (T2DM). The crosstalk between gut microbes and the host affects the inflammatory status and glucose tolerance of the individuals, but the underlying mechanisms have not been elucidated completely. In this study, we treated the lean chow diet-fed mice with Akkermansia muciniphila, which is thought to be inversely correlated with inflammation status and body weight in rodents and humans, and we found that A. muciniphila supplementation by daily gavage for five weeks significantly alleviated body weight gain and reduced fat mass. Glucose tolerance and insulin sensitivity were also improved by A. muciniphila supplementation compared with the vehicle. Furthermore, A. muciniphila supplementation reduced gene expression related to fatty acid synthesis and transport in liver and muscle; meanwhile, endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress in liver and muscle was also alleviated by A. muciniphila. More importantly, A. muciniphila supplementation reduced chronic low-grade inflammation, as reflected by decreased plasma levels of lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-binding protein (LBP) and leptin, as well as inactivated LPS/LBP downstream signaling (e.g. decreased phospho-JNK and increased IKBA expression) in liver and muscle. Moreover, metabolomics profiling in plasma also revealed an increase in anti-inflammatory factors such as alpha-tocopherol, beta-sitosterol and a decrease of representative amino acids. In summary, our study demonstrated that A. muciniphila supplementation relieved metabolic inflammation, providing underlying mechanisms for the interaction of A. muciniphila and host health, pointing to possibilities for metabolic benefits using specific probiotics supplementation in metabolic healthy individuals.