朱晓峰, 张桢, 崔雷鸿, 朱伟云, 杭苏琴

国家动物消化道国际联合中心, 南京农业大学动物科技学院, 消化道微生物研究室, 江苏 南京 210095

收稿日期:2020-02-29;修回日期:2020-05-13;网络出版日期:2020-06-08

基金项目:大学生创新创业训练专项计划(S20190015);农业部公益性行业专项(201403047)

*通信作者:杭苏琴, Tel:+86-25-84395037;E-mail:suqinhang69@njau.edu.cn.

摘要:[目的] 对3株乳酸杆菌和4种寡糖类益生元进行组合筛选,并探究其对猪结肠微生物体外发酵特性的影响。[方法] 将3株乳酸杆菌(罗伊氏乳杆菌L45、植物乳杆菌L47和罗伊氏乳杆菌L63)分别添加至以菊粉(inulin)、低聚果糖(FOS)、低聚半乳糖(GOS)或乳果糖(lactulose)为唯一碳源的培养基中,结合菌株24 h的生长活性和产酸特性,筛选出最优组合;进一步利用体外发酵技术探究所筛选合生元组合对微生物和发酵特性的影响。[结果] L45和L63分别以FOS和Lactulose为碳源发酵时的生长曲线与葡萄糖相似,L47发酵Inulin和FOS的△OD600显著高于葡萄糖(P < 0.05),且L47发酵Inulin产生的乳酸是葡萄糖的1.20倍,L47+FOS和L47+Inulin组合效应较好。体外发酵结果表明,与对照组相比,L47+FOS和L47+Inulin降低了发酵液中螺旋体门(Spirochaetes)的相对丰度,提高了乳杆菌属(Lactobacillus)和双歧杆菌属(Bifidobacterium)的相对丰度;L47+Inulin和L47+FOS显著提高了总短链脂肪酸含量(P < 0.05);与L47+Inulin组相比,L47+FOS组乙酸和丁酸含量更高(P < 0.05)。[结论] L47+FOS与L47+Inulin具有较好的组合效应,且具有改善猪结肠体外发酵的能力,提示L47+FOS和L47+Inulin作为合生元的发展潜力,两种组合在体内情况的效果有待深入研究。

关键词:益生菌益生元合生元乳酸杆菌体外发酵

Combination screening of lactobacillus spp. with prebiotics and analysis of its in vitro fermentation characteristics

Xiaofeng Zhu, Zhen Zhang, Leihong Cui, Weiyun Zhu, Suqin Hang

National Joint Research Center for Animal Digestive Tract Nutrition, Laboratory of Gastrointestinal Microbiology, College of Animal Science and Technology, Nanjing Agricultural University, Nanjing 210095, Jiangsu Province, China

Received: 29 February 2020; Revised: 13 May 2020; Published online: 8 June 2020

*Corresponding author: Suqin Hang, Tel:+86-25-84395037;E-mail:suqinhang69@njau.edu.cn.

Foundation item: Supported by the Special Training Program for College Student Innovation and Entrepreneurship (S20190015) and by the Ministry of Agriculture Public Welfare Project (201403047)

Abstract: [Objective] Three lactobacillus strains and four prebiotics for symbiotic combination were screened and their effects on in vitro colonic fermentation characteristics were investigated. [Methods] Lactobacillus reuteri L45, Lactobacillus plantarum L47 and Lactobacillus reuteri L63 were separately added to the medium with inulin, fructo-oligosaccharide, galacto-oligosaccharide or lactulose as the sole carbon source; the growth activity and acid production characteristics of the strains for 24 h were used to select the optimal combination; in vitro fermentation was used to investigate the effects of symbiotics on microorganisms and fermentation characteristics. [Results] The growth curves of L45 and L63 fermentation with fructo-oligosaccharide and lactulose as carbon sources were similar to glucose respectively; the OD600 of inulin and fructo-oligosaccharide with L47 was significantly higher than glucose (P < 0.05), and the lactic acid concentration of inulin was 1.20 times higher than glucose; L47 with fructo-oligosaccharide and L47 with Inulin have better composite effects. In vitro fermentation results showed that the combination of two synbiotics (L47+fructo-oligosaccharide and L47+Inulin) significantly increased the relative abundance of Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium compare to the control (P < 0.05); L47+FOS and L47+Inulin increased the concentration of total short chain fatty acid (P < 0.05). [Conclusion] L47+fructo-oligosaccharide and L47+Inulin had favorable combination effects, implying that they had the development potential as symbiotics. The effect of both combinations in vivo remains to further investigated.

Keywords: probioticsprebioticssymbioticsLactobacillusin vitro fermentation

近些年来,随着抗生素耐药菌的产生,微生态饲料添加剂替代动物抗生素促生长剂的研究引起了人们的关注。微生态制剂包括益生菌、益生元和合生元[1]。益生菌被定义为“能够通过改善肠道微生态,从而对宿主健康产生有益作用的活性微生物饲料添加剂”[2]。乳酸杆菌是一种主要的产乳酸菌,在畜禽生产中作为益生菌饲料添加剂被广泛使用[3]。研究表明,乳酸杆菌在生产上具有良好的益生性能,包括抗腹泻[4]和改善肠道微生态等[5]。

益生元是指一类不能被宿主自身消化的物质,能够选择性地促进肠道中特定菌群的生长或活性,从而改善宿主的健康[6]。寡糖类益生元如菊粉和低聚果糖能够改善肠道粘膜屏障[7],增加结肠中丁酸浓度[8]。益生元如低聚半乳糖和乳果糖能够影响猪回肠微生物发酵[9],改善仔猪生长性能[10]。益生菌与益生元以协同作用的形式结合,称之为合生元[9]。益生菌有利于促进肠道微生态平衡,而益生元可为益生菌提供营养底物,从而提高益生菌在胃肠道中的生存能力。动物胃肠道中的微生物是肠道天然屏障的重要组成部分,能产生大量的短链脂肪酸(short chain fatty acid,SCFAs),为结肠上皮细胞提供能量,还能作为信号分子影响机体的其他器官以及免疫系统等[11],所以在制备合生元时,益生菌和益生元的选择以及它们对肠道微生物的影响至关重要。许多研究表明,特定的合生元组合制剂能够对宿主产生有益的影响[12]。但由于这些研究在方法、剂量和持续时间等方面存在很大差异,且体内试验的时效性、可操作性较差,为了快速评估合生元对肠道微生物的影响,体外发酵模拟肠道环境逐渐成为研究肠道菌群及其代谢产物的一种便捷方法。

因此,本研究的目的是评价乳酸杆菌对不同寡糖类益生元的利用特点,并通过体外模拟结肠微生物发酵,探讨合生元组合对肠道微生物和发酵特性的影响,以期为畜禽生产中合生元饲料添加剂的开发提供参考。

1 材料和方法 1.1 菌株及培养条件 本实验室自行分离自健康猪胃肠道的3株乳酸杆菌(罗伊氏乳杆菌Lactobacillus reuteri L45、植物乳杆菌Lactobacillus plantarum L47和约氏乳杆菌Lactobacillus johnsonii L63)经鉴定具有潜在益生特性[13]。将–20 ℃冷冻保存的3株菌株分别接种于常规MRS培养基中,37 ℃培养20 h后,6000 r/min离心15 min,收集菌体并重悬至基础培养基中(carbohydrate-free MRS),用于后续试验。基础培养基参考Chin的配方并略微修改[14]:蛋白胨10.0 g、酵母提取物5.0 g、乙酸钠5.0 g、三水合磷酸氢二钾2.0 g、二水合柠檬酸三铵2.0 g、七水合硫酸镁0.2 g、四水合硫酸锰0.05 g、吐温-80 1 mL,调节至pH 6.2–6.4,120 ℃灭菌20 min。

1.2 益生元 4种寡糖类益生元:菊粉(inulin,纯度≥90%,聚合度32–34)、低聚果糖(fructo-oligosaccharide,FOS,纯度≥95%,聚合度2–10)、低聚半乳糖(galacto-oligosaccharides,GOS,纯度≥70%)和乳果糖(lactulose,纯度≥99%)购自上海源叶生物科技有限公司。

1.3 合生元组合筛选试验 基础培养基经120 ℃灭菌20 min后备用,将益生元溶解至去离子水中,过滤除菌(0.22 μm)后将1 mL益生元溶液以最终浓度为1% (W/V)的量添加至含有9 mL基础培养基试管中,葡萄糖为阳性对照,基础培养基为阴性对照。随后,将3株活化好的乳酸杆菌接种液分别以1% (V/V,1.0×109 CFU/mL)的接种量添加至各组培养基中,于37 ℃培养箱中厌氧培养24 h,结束后置于4 ℃冰盒上终止发酵,于0、3、6、9、12、15、18、21、24 h测定培养液光密度值(OD600),绘制生长曲线,并在培养结束后取样测定培养液pH和乳酸含量,每个处理3个重复。利用Logistic模型对生长曲线(公式1)数据进行拟合[15]。

| 公式(1) |

根据拟合曲线计算出最大增长速率(μmax)、OD600增加值(?OD600)和滞后期(lag period,λ)。本研究中,定义滞后期为达到最大增长速率(μmax)所需的时间;OD600增加值为拟合曲线OD600max值与初始OD600的差值。通过拟合曲线测定菌株利用益生元的生长情况,根据菌株的生长及产酸特性,筛选最优组合进行体外模拟猪结肠发酵试验。

1.4 合生元组合对猪结肠体外发酵影响评价

1.4.1 培养基和接种物的制备: 体外发酵使用所用的厌氧培养基参考Willims的方法配制[16],结肠食糜取自3头健康的杜×长×大育肥猪。以10% (W/V)的比例将采集的新鲜食糜加入至预热的37 ℃磷酸缓冲液中进行稀释,并使用4层无菌纱布将食糜稀释液过滤至持续通入CO2的厌氧发酵瓶中,作为接种液。

每个试管中加入8 mL培养基,使用丁基胶塞和铝盖进行封口,于120 ℃灭菌20 min。接种前将浓度为10% (W/V)的1 mL益生元过滤除菌后加入培养基中,39 ℃预热30 min。随后将1 mL食糜接种液和0.1 mL益生菌菌液(L. plantarum L47,109 CFU/mL)加入培养基中,于39 ℃厌氧培养24 h,结束后置于4 ℃冰盒上终止发酵。试验共分为6组:CON (control,对照组)、CON+L47、FOS、Inulin、L47+FOS和L47+Inulin (组合根据上一步试验筛选得出),每个处理3个重复。

1.4.2 微生物测序及其群落分析: 采用苯酚-氯仿抽提法提取发酵液中微生物总DNA,NanoDrop2000微量核酸蛋白测定仪(美国)检测DNA样本浓度,浓度 > 100 ng/μL、OD260/OD280为1.6–1.8的样品保存于–80 ℃。高通量测序对发酵液中微生物群落结构及多样性进行分析。引物341F (5′-AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3′)和806R (5′-TTACCGCGGCTGCTGGCAC-3′)对16S rRNA基因V3–V4可变区进行扩增,于IlluminateHiseq2500 (上海美吉生物医药有限公司)平台完成测序。利用QIIME软件将数据过滤,通过Flash软件对有overlap的一对reads进行拼接。根据序列的相似性,用UClust软件将97%相似性的序列归为多个OTU (operational taxonomic unit,操作分类单元),RDP classifier对序列进行物种注释。通过丰富度指数(Chao1、Ace)、多样性指数(Shannon、Simpson)对发酵液中菌群α-多样性进行分析,根据OTU相对丰度对发酵液中菌落组成进行门水平、属水平分析。

1.4.3 微生物发酵参数的测定: 参照Theodorou的方法,利用气压转换仪定时(0、6、12、18、24 h)测定发酵瓶内的产气量,各时间点产气量的总和为累计产气量[17]。使用pH计对发酵上清液中pH进行测定。乳酸检测采用南京建成生物工程研究所提供的乳酸测试盒进行测定。取1 mL上清液到2 mL离心管中,加入0.2 mL的25% (W/V)偏磷酸巴豆酸混合溶液,于–20 ℃过夜保存,测定前通过0.22 μm滤器进行过滤。参照秦为琳[18]的方法使用气相色谱(Shimadzu GC-2014,日本)检测样品中短链脂肪酸(short chain fatty acid,SCFA)浓度。

1.5 数据统计与分析 数据以“Mean±SD”表示,采用Graphpad Prism 7.0软件进行作图,通过SPSS 20.0统计软件,进行单因素方差分析(oneway-ANOVA),测序数据使用和非参数检验(Kruskal-Wallis和post-hoc Dunn-Bonferroni检验);菌株生长参数采用OriginPro 2017进行拟合。显著性水平为P < 0.05,用不同小写字母上标表示;显著性水平为P > 0.05,用相同小写字母上标表示。

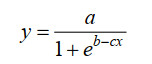

2 结果和分析 2.1 益生元对乳酸杆菌生长特性的影响 菌株的生长曲线如图 1所示。通过logistic模型拟合生长曲线相关参数(表 1),拟合曲线回归系数(R2)均大于0.99 (数据未显示),说明数据拟合较好。

|

| 图 1 乳酸杆菌以不同益生元为碳源的生长曲线 Figure 1 Growth curves of L. reutri L45 (A), L. plantarum L47 (B) and L. johnsonii L63 (C) under different prebiotic as carbohydrate sources. The data points represent mean and error bars represent standard deviation of 3 replicates. |

| 图选项 |

表 1. 乳酸杆菌以不同益生元为碳源的生长动力学参数 Table 1. Kinetic parameter of Lactobacillus spp. under different prebiotic as carbohydrate sources

| Parameters | Strains | Basal medium | Glucose | Inulin | FOS | GOS | Lactulose |

| ?OD600 | L45 | 0.15±0.01f | 0.53±0.00b | 0.24±0.01e | 0.60±0.01a | 0.42±0.01d | 0.45±0.01c |

| L47 | 0.17±0.00f | 0.86±0.01c | 0.96±0.01a | 0.93±0.01b | 0.30±0.02d | 0.26±0.01e | |

| L63 | 0.11±0.00e | 0.81±0.01c | 0.87±0.01b | 0.81±0.01c | 0.68±0.01d | 0.89±0.01a | |

| μmax | L45 | 0.06±0.01c | 0.11±0.00b | 0.06±0.00c | 0.12±0.01b | 0.18±0.04a | 0.12±0.01b |

| L47 | 0.05±0.01c | 0.25±0.01a | 0.18±0.01b | 0.20±0.03b | 0.02±0.00d | 0.04±0.00cd | |

| L63 | 0.02±0.00c | 0.21±0.01a | 0.21±0.05a | 0.04±0.00c | 0.21±0.01a | 0.14±0.00b | |

| λ | L45 | 2.50±0.12d | 3.67±0.49b | 3.30±0.28bc | 3.19±0.11c | 6.42±0.09a | 6.58±0.14a |

| L47 | 6.30±0.14c | 6.30±0.06c | 7.94±0.22b | 8.71±0.23a | 5.11±0.53d | 5.99±0.29c | |

| L63 | 4.30±0.15d | 3.07±0.05e | 8.78±0.29b | 11.20±0.32a | 8.07±0.26c | 4.62±0.48d | |

| FOS: fructo-oligosaccharide; GOS: galacto-oligosaccharides; ΔOD600: increase in OD600; μmax: maximum growth rate; λ: lag time. Data in the same row with the different letters mean significant difference (P < 0.05), and with the same letter mean no significant difference (P > 0.05). | |||||||

表选项

相对于其他益生元,L45在以FOS为碳源发酵的?OD600最高(P < 0.05),且μmax (最大生长速率)与葡萄糖相比无显著差异(P > 0.05),λ值(滞后期)均低于其他几种益生元,说明L45对FOS利用能力较好;L47发酵Inulin和FOS的?OD600显著高于葡萄糖(P < 0.05),且于9–12 h之后进入生长稳定期,随后曲线开始趋于平稳,而在GOS和Lactulose中观察到的?OD600水平较低,表明L47对FOS和Inulin利用较好,但对GOS和Lactulose的利用较差;L63在以Lactulose、Inulin为碳源发酵时表现出相似的生长活性,其?OD600均高于葡萄糖组,以FOS为碳源发酵24 h后,虽然?OD600达到了较高水平(0.81),但其λ值却达到了11.20,且未观察到生长稳定期,说明L63对Inulin和Lactulose的利用情况较好。

2.2 益生元对乳酸杆菌产酸特性的影响 乳酸杆菌利用不同碳源生长24 h的pH变化值和乳酸浓度如表 2所示,L45和L63在利用葡萄糖发酵后pH降低值最高(分别为–1.60和–1.46),且两株菌在发酵葡萄糖时产乳酸浓度最高(80.95和72.79 mmol/L);此外,L47发酵Inulin产生的乳酸是葡萄糖的1.2倍(103.06 vs. 85.71),且pH降低值在葡萄糖、Inulin和FOS组之间无显著差异,说明L47+Inulin、L47+FOS组合效果较好,可用于下一步试验。

表 2. 乳酸杆菌以不同益生元为碳源的pH降低值和乳酸 Table 2. The lactic acid and decrease of pH of Lactobacillus spp. under different prebiotic as carbohydrate sources

| Parameters | Strains | Basal medium | Glucose | Inulin | FOS | GOS | Lactulose |

| Decrease of pH | L45 | –0.03±0.02f | –1.60±0.03a | –0.37±0.04e | –1.44±0.01c | –1.24±0.01d | –1.53±0.02b |

| L47 | 0.02±0.03d | –1.71±0.03a | –1.77±0.01a | –1.74±0.04a | –0.22±0.02c | –0.45±0.03b | |

| L63 | –0.00±0.07c | –1.46±0.01a | –1.42±0.02ab | –1.31±0.04b | –1.44±0.05a | –1.39±0.01ab | |

| Lactic acid/ (mmol/L) | L45 | –0.34±4.82e | 80.95±4.25a | 38.44±2.13d | 74.29±1.41ab | 65.31±2.04c | 71.09±1.56bc |

| L47 | –0.34±2.12d | 85.71±2.05b | 103.33±3.82a | 88.78±3.68b | 43.20±1.56c | 40.14±5.14c | |

| L63 | 2.72±5.13d | 72.79±5.13a | 54.76±3.86bc | 44.90±4.08c | 56.12±2.7bc | 64.63±3.12ab | |

| FOS: fructo-oligosaccharide; GOS: Galacto-oligosaccharides. Data in the same row with the different letters mean significant difference (P < 0.05), and with the same letter mean no significant difference (P > 0.05). | |||||||

表选项

2.3 L47+FOS和L47+Inulin对发酵液中菌群的丰富度和多样性的影响 Ace和Chao1指数反映了微生物丰富度,Shannon和Simpson指数可反映微生物的多样性。如表 3所示,添加两种合生元对Ace、Chao1、Shannon和Simpson指数无显著影响(P > 0.05)。说明添加合生元(L47+FOS和L47+Inulin)不改变发酵液中菌群的丰富度和多样性。

表 3. 发酵液微生物丰富度和多样性 Table 3. Richness and diversity of microbiota in fermented broth

| Items | Coverage | Ace | Chao1 | Shannon | Simpson |

| Control | 1.00±0.00 | 681.41±19.32 | 684.17±19.32 | 88.75±11.82 | 0.04±0.01 |

| L47+FOS | 1.00±0.00 | 598.47±15.86 | 604.75±30.65 | 26.33±2.54 | 0.12±0.01 |

| L47+Inulin | 1.00±0.00 | 553.47±61.36 | 554.16±63.92 | 26.55±1.75 | 0.11±0.01 |

| P-value | 0.051 | 0.061 | 0.051 | 0.066 | 0.051 |

| FOS: fructo-oligosaccharide. | |||||

表选项

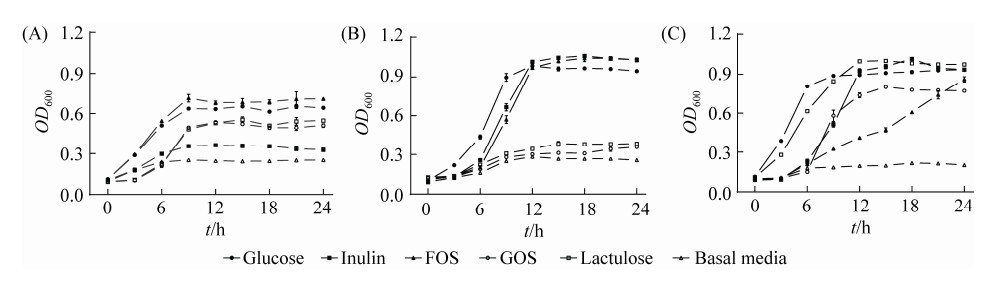

2.4 L47+FOS和L47+Inulin对发酵液中菌群组成的影响 在门水平上,发酵液中微生物以梭杆菌门(Fusobacteria)、厚壁菌门(Firmbacteria)、拟杆菌门(Bacteroidetes)和变形菌门(Proteobacteria)为主(图 2-A);添加合生元(L47+FOS或L47+Inulin)显著降低了螺旋体门(Spirochaetes)的相对丰度(图 2-C)。

|

| 图 2 发酵液中微生物的组成以及具有差异的菌群 Figure 2 Relative abundance (percentage) of bacterial community in phylum (A) and genus (B) in fermented broth. Changes in the relative abundance of Spirochaetes (C), Lactobacillus (D), Bifidobacteria (E), Anaerovibrio (F), Lachnoclostridium (G) and Megasphaera (H). Horizontal bars indicate the minimum values, the 25th, 50th, 75th percentile levels, and the maximum values. * indicates a P < 0.05 as compared with the control. |

| 图选项 |

在属水平上,三组以梭杆菌属(Fusobacterium)和拟杆菌属(Bacteroides)为优势菌属(图 2-B)。合生元组中乳杆菌属(Lactobacillus)、双歧杆菌属(Bifidobacterium)和厌氧弧菌属(Anaerovibrio)显著高于对照组(P < 0.05) (图 2-D,E和F);而毛螺梭菌属(Lachnoclostridium)则显著低于对照组(P < 0.05) (图 2-G);而Megasphaera菌属在L47+FOS和L47+Inulin组中明显有一个重复升高(图 2-B),但差异不显著(P > 0.05) (图 2-H);以上结果说明合生元制剂改变了发酵液中微生物的组成。

2.5 L47+FOS和L47+Inulin对体外发酵参数的影响 如表 4所示,L47+FOS和L47+Inulin组产气量和pH值显著低于单独添加益生元(FOS、Inulin)组(P < 0.05);与单独添加Inulin组相比,单独添加FOS组的乳酸含量更低,乙酸和总短链脂肪酸含量更高(P < 0.05);此外,与L47+Inulin组相比,L47+FOS组丁酸含量更高。

表 4. 植物乳杆菌L47与菊粉、低聚果糖组合的体外发酵参数 Table 4. In vitro fermentation parameters of L. plantarum L47 compounded with Inulin and FOS

| Items | CON | CON+L47 | FOS | INU | FOS+L47 | INU+L47 |

| Gas production/mL | ND | ND | 19.07±0.15b | 20.10±0.10a | 16.27±0.35d | 17.97±0.49c |

| pH | 6.40±0.02a | 6.35±0.02a | 4.34±0.04b | 4.16±0.03c | 3.94±0.02d | 3.97±0.01d |

| Lactic acid/(mmol/L) | 14.34±2.51d | 17.70±2.68d | 28.88±3.35c | 39.44±2.15b | 55.77±2.98a | 61.21±2.67a |

| Acetic acid/(mmol/L) | 6.79±0.86b | 6.51±0.47b | 13.71±1.52a | 8.04±0.75b | 17.12±1.76a | 9.74±1.66b |

| Propionic acid/(mmol/L) | 0.84±0.18b | 0.92±0.07b | 4.26±1.47a | 2.60±0.27ab | 3.97±1.64a | 3.91±0.57a |

| Butyric acid/(mmol/L) | 0.87±0.02c | 0.76±0.03c | 4.03±0.42ab | 2.81±0.46b | 4.46±1.12a | 2.88±0.17b |

| Valeric acid/(mmol/L) | 0.44±0.13 | 0.63±0.48 | 0.28±0.22 | 0.11±0.02 | 0.36±0.28 | 0.13±0.09 |

| BCFA/(mmol/L) | 0.39±0.19b | 0.24±0.07b | 0.27±0.19b | 0.87±0.40ab | 0.96±0.21ab | 1.38±0.41a |

| TSCFA/(mmol/L) | 9.33±0.94d | 9.06±0.95d | 22.56±2.73b | 14.43±0.90c | 26.87±0.77a | 18.04±1.36b |

| CON: control; INU: inulin; ND: not detected; BCFA: branch chain fatty acid; TSCFA: total short chain fatty acid. Data in the same row with the different letters mean significant difference (P < 0.05), and with the same letter mean no significant difference (P > 0.05). | ||||||

表选项

3 讨论 有效的合生元组合需满足益生元对益生菌的促生长作用,因此我们通过体外培养试验对两者的组合效应进行了评价。结果发现3株乳酸杆菌能利用FOS进行生长(?OD600 > 0.60),而只有L45和L63能够发酵GOS和Lactulose。此外,L47利用Inulin和FOS进行发酵的?OD600优于葡萄糖,且L47发酵Inulin 24 h的乳酸浓度是葡萄糖的1.20倍(103.33 vs. 80.95)。说明3株乳酸杆菌对发酵4种益生元的生长活性存在差异。乳酸杆菌能够通过产酸降低肠道pH,从而抑制病原菌的生长。3株乳酸杆菌能够利用FOS和Inulin代谢产酸,且L47发酵FOS和Inulin产乳酸浓度是其他2株菌的1.20–2.69倍。这可能是由于不同乳酸杆菌发酵寡糖产酸的代谢途径不同[19],且本试验中3株菌对酸性环境的耐受性也不同[13],可见不同乳酸菌对益生元的利用存在差异。Su等研究了10种不同益生元对不同乳酸杆菌生长的影响[20],发现菌株对不同益生元的利用程度不同。一些关于乳酸杆菌对FOS的代谢研究表明,不同乳酸杆菌之间可能具有不同的酶活性和底物运输系统,使其能够利用特定的寡糖类益生元[21]。特定的酶活性导致菌株在不同的益生元底物中表现出不同的生长模式,因此,益生元的有效性取决于它被特定菌群选择性发酵的能力。以上结果表明,寡糖类益生元能够在体外促进乳酸杆菌的生长,但菌株对益生元的具体选择性代谢机制还有待进一步分析。

通过试验筛选出两组组合效应较好的合生元(L47+FOS和L47+Inulin)进行体外模拟猪结肠发酵试验,发现添加合生元制剂对发酵液中微生物的丰富度和多样性无显著性影响(P > 0.05)。添加合生元对厚壁菌门(Firmbacteria)和拟杆菌门(Bacteroidetes)的相对丰度无显著影响(P > 0.05)。然而,据Myhill等[7]报道,日粮中添加菊粉降低了猪肠道中厚壁菌门,提高了拟杆菌门相对丰度。Frese等[22]指出,随着猪年龄的增长,其肠道菌群多样性增加的同时,其菌群多样性指数的变异性降低。此外,Niu等[23]还表明,猪在90–150日龄时肠道菌群多样性趋于稳定。而本研究微生物样品来自于育肥猪(≥150日龄),这可能是合生元对菌群多样性及门水平菌群影响较小的原因之一。合生元组发酵液中乳酸的升高可能与乳杆菌属(Lactobacillus)和双歧杆菌属(Bifidobacterium)的升高有关,也可能是由于外源乳酸杆菌L47所引起,但由于本研究未能对外源性L47及益生元对微生物的影响进行检测,其原因有待于进一步研究。此外,合生元组中乳酸利用菌厌氧弧菌属(Anaerovibrio)[24]和巨球菌属(Megasphaera)[25]的升高可能与乳酸的升高有关。研究表明厌氧弧菌(Anaerovibrio)能够利用乳酸产生乙酸和丙酸[24],而巨球菌属(Megasphaera)[25]能够利用乳酸产生丁酸[25],本试验中合生元组发酵液中乙酸、丙酸和丁酸的升高也映证了这一点。本研究Fusobacteria菌门的相对丰度较高,Fusobacteria通常被认为是宿主感染和肠道疾病相关的致病菌[26],也提示合生元可能会导致病原菌的入侵、富集。但由于体外模型不能够完全模拟体内环境,所以合生元的安全性还有待进一步体内试验验证。一些对益生菌和益生元的研究表明,体外和体内试验结果相一致[27-28],说明尽管体外发酵模型具有一定缺陷,但其结果能够为体内试验的开展起到预示作用。

肠道微生物生长代谢能够产生乳酸、短链脂肪酸和气体等。本研究结果发现,添加L47+FOS和L47+Inulin的产气量显著低于单独添加Inulin或FOS组(P < 0.05)。FOS组TSCFA浓度显著高于Inulin组(P < 0.05),这与前人的研究相似。Stewart等[29]研究发现,接种人类粪便微生物发酵FOS的速度比Inulin更快,这可能与寡糖的聚合度长短有关,而本研究所用FOS和Inulin聚合度分别为10和32–34。微生物发酵过程中产生的乳酸和SCFAs除了能够作为肠上皮细胞和菌群的能量来源外,还能够影响肠道生理的各个方面。据报道,双歧杆菌产生的乙酸可提高上皮细胞对致病性大肠杆菌E. coli O157:H7感染的防御能力[30]。而丁酸主要由结肠上皮细胞代谢,是主要的能量来源,也是细胞生长和分化的调节因子[31]。由此我们推断,添加合生元制剂能够在体外影响肠道微生物发酵。

综上所述,乳酸杆菌对寡糖类益生元在体外的利用具有菌株特异性;L47+FOS或L47+Inulin组合改变了模拟猪后肠发酵环境中菌群和短链脂肪酸的产生,但由于本研究所利用的体外发酵技术与体内的真实情况具有一定的差异,无法完整描述结肠微生物的变化,因此,两种组合在体内对微生物的影响有待深入研究。

References

| [1] | Markowiak P, ?li?ewska K. The role of probiotics, prebiotics and synbiotics in animal nutrition. Gut Pathogens, 2018, 10: 21. |

| [2] | Afrc RF. Probiotics in man and animals. Journal of Applied Bacteriology, 1989, 66(5): 365-378. DOI:10.1111/j.1365-2672.1989.tb05105.x |

| [3] | Dowarah R, Verma AK, Agarwal N. The use of Lactobacillus as an alternative of antibiotic growth promoters in pigs:a review. Animal Nutrition, 2017, 3(1): 1-6. |

| [4] | Huang CH, Qiao SY, Li DF, Piao XS, Ren JP. Effects of Lactobacilli on the performance, diarrhea incidence, VFA concentration and gastrointestinal microbial flora of weaning pigs. Asian-Australasian Journal of Animal Sciences, 2004, 17(3): 401-409. DOI:10.5713/ajas.2004.401 |

| [5] | Roselli M, Pieper R, Rogel-Gaillard C, de Vries H, Bailey M, Smidt H, Lauridsen C. Immunomodulating effects of probiotics for microbiota modulation, gut health and disease resistance in pigs. Animal Feed Science and Technology, 2017, 233: 104-119. DOI:10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2017.07.011 |

| [6] | Gibson GR, Roberfroid MB. Dietary modulation of the human colonic microbiota:introducing the concept of prebiotics. The Journal of Nutrition, 1995, 125(6): 1401-1412. DOI:10.1093/jn/125.6.1401 |

| [7] | Myhill LJ, Stolzenbach S, Hansen TVA, Skovgaard K, Stensvold CR, Andersen LO, Nejsum P, Mejer H, Thamsborg SM, Williams AR. Mucosal barrier and Th2 immune responses are enhanced by dietary inulin in pigs infected with Trichuris suis. Frontiers in Immunology, 2018, 9: 2557. DOI:10.3389/fimmu.2018.02557 |

| [8] | Le Bourgot C, Le Normand L, Formal M, Respondek F, Blat S, Apper E, Ferret-Bernard S, Le Hu?rou-Luron I. Maternal short-chain fructo-oligosaccharide supplementation increases intestinal cytokine secretion, goblet cell number, butyrate concentration and Lawsonia intracellularis humoral vaccine response in weaned pigs. British Journal of Nutrition, 2017, 117(1): 83-92. |

| [9] | Smiricky-Tjardes MR, Grieshop CM, Flickinger EA, Bauer LL, Fahey Jr GC. Dietary galactooligosaccharides affect ileal and total-tract nutrient digestibility, ileal and fecal bacterial concentrations, and ileal fermentative characteristics of growing pigs. Journal of Animal Science, 2003, 81(10): 2535-2545. DOI:10.2527/2003.81102535x |

| [10] | Guerra-Ordaz AA, González-Ortiz G, La Ragione RM, Woodward MJ, Collins JW, Pérez JF, Martin-Orúe SM. Lactulose and Lactobacillus plantarum, a potential complementary synbiotic to control postweaning colibacillosis in piglets. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2014, 80(16): 4879-4886. DOI:10.1128/AEM.00770-14 |

| [11] | Le Poul E, Loison C, Struyf S, Springael JY, Lannoy V, Decobecq ME, Brezillon S, Dupriez V, Vassart G, Van Damme J, Parmentier M, Detheux M. Functional characterization of human receptors for short chain fatty acids and their role in polymorphonuclear cell activation. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 2003, 278(28): 25481-25489. DOI:10.1074/jbc.M301403200 |

| [12] | Awad WA, Ghareeb K, Abdel-Raheem S, B?hm J. Effects of dietary inclusion of probiotic and synbiotic on growth performance, organ weights, and intestinal histomorphology of broiler chickens. Poultry Science, 2009, 88(1): 49-56. DOI:10.3382/ps.2008-00244 |

| [13] | Li XL, Wang C, Yu DF, Ding LR, Zhu WY, Hang SQ. Isolation, identification and characterization of lactic acid bacteria from swine. Acta Microbiologica Sinica, 2017, 57(12): 1879-1887. (in Chinese) 李雪莉, 王超, 虞德夫, 丁立人, 朱伟云, 杭苏琴. 猪源乳酸菌的分离、鉴定及其生物学特性. 微生物学报, 2017, 57(12): 1879-1887. |

| [14] | Saminathan M, Sieo CC, Kalavathy R, Abdullah N, Ho YM. Effect of prebiotic oligosaccharides on growth of Lactobacillus strains used as a probiotic for chickens. African Journal of Microbiology Research, 2011, 5(1): 57-64. |

| [15] | Annadurai G, Babu SR, Srinivasamoorthy VR. Development of mathematical models (Logistic, Gompertz and Richards models) describing the growth pattern of Pseudomonas putida (NICM 2174). Bioprocess Engineering, 2000, 23(6): 607-612. DOI:10.1007/s004490000209 |

| [16] | Williams BA, Bosch MW, Boer H, Verstegen MWA, Tamminga S. An in vitro batch culture method to assess potential fermentability of feed ingredients for monogastric diets. Animal Feed Science and Technology, 2005, 123-124: 445-462. DOI:10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2005.04.031 |

| [17] | Theodorou MK, Williams BA, Dhanoa MS, McAllan AB, France J. A simple gas production method using a pressure transducer to determine the fermentation kinetics of ruminant feeds. Animal Feed Science and Technology, 1994, 48(3/4): 185-197. |

| [18] | Qin WL. Determ naton of rumen volatile fatty acids by means of gas chromatography. Journal of Nanjing Agricultural College, 1982(4): 110-116. (in Chinese) 秦为琳. 应用气相色谱测定瘤胃挥发性脂肪酸方法的研究改进. 南京农学院学报, 1982(4): 110-116. |

| [19] | Hofvendahl K, Hahn-H?gerdal B. Factors affecting the fermentative lactic acid production from renewable resources1. Enzyme and Microbial Technology, 2000, 26(2/4): 87-107. |

| [20] | Su P, Henriksson A, Mitchell H. Selected prebiotics support the growth of probiotic mono-cultures in vitro. Anaerobe, 2007, 13(3/4): 134-139. |

| [21] | Saulnier DMA, Molenaar D, De Vos WM, Gibson GR, Kolida S. Identification of prebiotic fructooligosaccharide metabolism in Lactobacillus plantarum WCFS1 through microarrays. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2007, 73(6): 1753-1765. |

| [22] | Frese SA, Parker K, Calvert CC, Mills DA. Diet shapes the gut microbiome of pigs during nursing and weaning. Microbiome, 2015, 3: 28. |

| [23] | Niu Q, Li PH, Hao SS, Zhang YQ, Kim SW, Li HZ, Ma X, Gao S, He LC, Wu WJ, Huang XG, Hua JD, Zhou B, Huang R. Dynamic distribution of the gut microbiota and the relationship with apparent crude fiber digestibility and growth stages in pigs. Scientific Reports, 2015, 5: 9938. |

| [24] | Ohashi Y, Ushida K. Health-beneficial effects of probiotics:its mode of action. Animal Science Journal, 2009, 80(4): 361-371. |

| [25] | Hashizume K, Tsukahara T. Yamada K, Koyama H, Ushida K. Megasphaera elsdenii JCM1772T normalizes hyperlactate production in the large intestine of fructooligosaccharide-fed rats by stimulating butyrate production. The Journal of Nutrition, 2003, 133(10): 3187-3190. |

| [26] | Harris DL, Alexander TJ, Whipp SC, Robinson IM, Glock RD, Matthews PJ. Swine dysentery:studies of gnotobiotic pigs inoculated with Treponema hyodysenteriae, Bacteroides vulgatus, and Fusobacterium necrophorum. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association, 1978, 172(4): 468-471. |

| [27] | Amaretti A, Di Nunzio M, Pompei A, Raimondi S, Rossi M, Bordoni A. Antioxidant properties of potentially probiotic bacteria:in vitro and in vivo activities. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology, 2013, 97(2): 809-817. |

| [28] | Molan AL, Lila MA, Mawson J, De S. In vitro and in vivo evaluation of the prebiotic activity of water-soluble blueberry extracts. World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology, 2009, 25(7): 1243-1249. |

| [29] | Stewart ML, Timm DA, Slavin JL. Fructooligosaccharides exhibit more rapid fermentation than long-chain inulin in an in vitro fermentation system. Nutrition Research, 2008, 28(5): 329-334. |

| [30] | Fukuda S, Toh H, Hase K, Oshima K, Nakanishi Y, Yoshimura K, Tobe T, Clarke JM, Topping DL, Suzuki T, Taylor TD, Itoh K, Kikuchi J, Morita H, Hattori M, Ohno H. Bifidobacteria can protect from enteropathogenic infection through production of acetate. Nature, 2011, 469(7331): 543-547. |

| [31] | Roberfroid M, Gibson GR, Hoyles L, McCartney AL, Rastall R, Rowland I, Wolvers D, Watzl B, Szajewska H, Stahl B, Guarner F, Respondek F, Whelan K, Coxam V, Davicco MJ, Léotoing L, Wittrant Y, Delzenne NM, Cani PD, Neyrinck AM, Meheust A. Prebiotic effects:metabolic and health benefits. British Journal of Nutrition, 2010, 104 Suppl 2: S1-S53. |