唐凯1, 贾丽娟1, 高晓丹1, 陶羽1, 孟建宇1, 李蘅1, 袁立敏2, 冯福应1

1.内蒙古农业大学生命科学学院, 应用与环境微生物研究所, 内蒙古 呼和浩特 010018;

2.内蒙古自治区林业科学研究院, 内蒙古 呼和浩特 010010

收稿日期:2017-03-03;修回日期:2017-06-09;网络出版日期:2017-07-10

基金项目:国家自然科学基金(31560030);国家科技支撑计划(2015BAC06B01);内蒙古自治区高等学校“青年科技英才支持计划”(NJYT-14-A05)

*通信作者:冯福应, Tel:+86-471-4309240;E-mail:foyefeng@hotmail.com

摘要:[目的]揭示浑善达克沙地不同类型生物土壤结皮(Biological soil crusts,BSCs)及其下层土壤好氧不产氧光营养细菌(Aerobic anoxygenic phototrophic bacteria,AAPB)群落结构及多样性。[方法]利用Illumina MiSeq二代高通量测序平台对pufM基因进行测序,使用生物信息学分析方法对序列进行比对分析AAPB的群落结构和多样性。[结果]生物土壤结皮及其下层土壤中,Proteobacteria和Alpha-Proteobacteria是优势门和纲,主要有6个属Bradyrhizobium(9.69%-90.02%)、Brevundimonas(0.83%-16.04%)、Methylobacterium(1.74%-12.56%)、Rhodospirillum(0.91%-32.87%)、Roseiflexus(0.02%-1.79%)和Sphingomonas(0.13%-11.23%);结皮层样品间及下层土壤样品间AAPB种类相似,但丰度有差异;随结皮的发育,结皮层及其下层土壤中AAPB群落多样性升高。[结论]浑善达克沙地BSCs中AAPB群落结构相对复杂,与水体和一般土壤环境中的组成区别明显;AAPB多样性高,且多样性随发育阶段升高而升高,预示着AAPB在荒漠生态系统稳定中有重要的作用。

关键词: BSCs AAPB pufM 高通量测序 多样性

Community structure and diversity of aerobic anoxygenic phototrophic bacteria in soil crusts and subsoil of Hunshandake deserts

Kai Tang 1, Lijuan Jia 1, Xiaodan Gao 1, Yu Tao 1, Jianyu Meng 1, Heng Li 1, Limin Yuan 2, Fuying Feng 1

1.Institute for Applied & Environmental Microbiology, College of Life Sciences, Inner Mongolia Agricultural University, Hohhot 010018, Inner Mongolia Autonomous, China;

2.Inner Mongolia Academy of Forestry Science, Hohhot 010010, Inner Mongolia Autonomous, China

Received 3 March 2017; Revised 9 June 2017; Published online 10 July 2017

*Corresponding author: Fuying Feng, Tel: +86-471-4309240; E-mail:foyefeng@hotmail.com

Supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31560030), by the National Science and Technology Support Program (2015BAC06B01) and by the Program for Young Talents of Science and Technology in Universities of Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region (NJYT-14-A05)

Abstract: [Objective]To discover the community structure and diversity of aerobic anoxygenic phototrophic bacteria (AAPB) in different types of soil crusts (BSCs) and soils under them.[Methods]The pufM gene was sequenced via the Illumina MiSeq second-generation high-throughput sequencing platform, and the community structure and diversity of AAPB were analyzed by bioinformatics analysis.[Results]In the BSCs and soils under them, Proteobacteria and Alpha-Proteobacteria were the main phylum, and the main genus were Bradyrhizobium (9.69% to 90.02%), Brevundimonas (0.83% to 16.04%), Methylobacterium (1.74% to 12.56%), Rhodospirillum (0.91% to 32.87%), Roseiflexus (0.02% to 1.79%) and Sphingomonas (0.13% to 11.23%). Biological soil crusts and soil under them had the similar community structure, but different in the abundance. With the development of BSCs, the species richness and diversity of the crusts and their underlying soils increased.[Conclusion]The community structure of AAPB in BSCs of Hunshandake sandy land is relatively complex, which is significant different from that in water and general soil environment. The diversity of AAPB is high and the diversity increases with the BSCs development, which suggests that AAPB plays an important role in the stability of desert ecosystem.

Key words: BSCs AAPB pufM high-throughput sequencing diversity

好氧不产氧光营养细菌(Aerobic anoxygenic phototrophic bacteria,AAPB),是一类需氧不产氧光能异养细菌,其光能利用由细菌叶绿素介导。AAPB因在海洋中大量和广泛分布及其对碳代谢的影响而备受关注[1]。后来发现AAPB在火山口湖[2]、高原湖泊[3]和沼泽[4]等淡水环境中也大量存在,预示其在水生生态系统中有重要功能。然而与此相比,AAPB在荒漠中的分布却鲜有研究报道。

生物土壤结皮(Biological soil crusts,BSCs)分布广泛,从热带到极地地区均有发现,是荒漠生态系统的主要组成和景观之一[5]。BSCs是由微观的(蓝细菌、藻类、真菌和细菌)和宏观的(地衣、苔藓和微小节肢动物)生物体形成的、常存在于土壤表层的复合体[6]。根据生物土壤结皮中优势生物组分及其生长形态、功能、土壤基质和演替阶段,BSCs可分为藻结皮(Algae crusts)、地衣结皮(Lichen crusts)和苔藓结皮(Moss crusts) 3种主要类型[7]。微生物在BSCs的各个发育阶段都具有重要而积极的作用[8-9]。但以往有关研究主要集中于BSCs类型和分布、形成机理和生态功能等方面,对其中的微生物组成和功能了解还不够全面和系统[10-11]。光能利用微生物是BSCs中最重要的功能组分。具光合固碳、固氮和产多糖等功能的蓝藻一直被认为是BSCs形成发展的关键光能利用微生物。而AAPB也具有许多相似功能[12],可能对BSCs发展有积极贡献。认识群落结构和多样性是理解AAPB与BSCs发育关系的基础。但截止目前为止,仅有Csotonyi等[13]利用传统涂布划线方法研究了BSCs中的AAPB群落,结果表明总分离物中的0.1%–5.9%为AAPB,它们仅划分为4个属。而AAPB群落广泛存在于Proteobacteria、Chlorobi、Chloroflexi、Firmicute、Acidobacteria和Gemmatimonadetes 6个门类[14],Sandaracinobacte、Erythromonas、Erythromicrobium、Roseococcus、Porphyrobacter、Acidiphilium、Roseateles、Erythrobacter、Roseobacter、Citromicrobium、Rubrimonas、Roseovarius、Roseivivax、Craurococcus、Paracraurococcus等近20属。但由于土壤中99%以上的微生物以现有技术不能实现纯化培养,基于分离培养方法揭示出的BSCs中AAPB群落结构和多样性极不全面,还有待基于分子生物学方法全面系统地研究揭示。作为编码AAPB光反应中心小亚基的pufM基因,数据库庞大,便于系统地比较各类环境中AAPB群落结构的差异,已广泛应用于AAPB多样性和进化分析[15-16]。Zeng等[17]利用DOTUR软件研究分析AAPB属、种pufM序列之间的距离之后认为,pufM序列距离进行种的分类的cutoff值为0.06。

综上,本研究以浑善达克沙地为例,采集分布于其中的藻结皮、地衣结皮和苔藓结皮及其下层土壤,利用Miseq高通量测序技术(High-throughput sequencing,HTS)对pufM基因进行测序,对比分析不同类型BSCs中AAPB群落结构和多样性,以期为认识和理解AAPB在BSCs的分布和生态功能,及其对于在荒漠生态系统环境的修复潜力提供理论依据。

1 材料和方法 1.1 生物土壤结皮的采集和处理 本研究样品于2015年6月采自内蒙古浑善达克沙地东南边缘姑娘湖附近(42.427N,116.769E,海拔1380 m)。在3个间隔100–500 m的不同区域,利用5点采样法,使用灭菌且锋利的小刀,分别采集藻结皮、地衣结皮和苔藓结皮3类不同类型生物土壤结皮(土表层1–2 cm)及其下层土壤(结皮下层2–5 cm)、相应混合均匀,分别命名为HSA (藻结皮层)、HSAs (藻结皮下层土壤)、HSL (地衣结皮层)、HSLs (地衣结皮下层土壤)、HSM (苔藓结皮层)和HSMs (苔藓结皮下层土壤)。所采样品放入50 mL无菌离心管,置于液氮中,运至实验室于–80低温冰箱保存备用。

1.2 样品总DNA的提取 将相同类型的5个土壤样品混合均匀,取0.5 g按照E.Z.N.A. Soil DNA Kit说明书进行样品总DNA的提取,提取的DNA溶于50 mL无菌超纯水中,使用Nanodrop 2000超微量核酸定量仪对浓度和质量进行检测。重复3次,将3次DNA混合均匀,置于–80℃低温冰箱保藏。

1.3 高通量测序 以pufM基因作为AAPB群落结构多样性的分子标尺,各样品DNA为模板,引物pufM 557F:CGCACCTGGACTGGAC,pufM_WAW:AYNGCRAACCACCANGCCCA[18],扩增片段长度在270 bp左右。PCR反应条件为:95℃ 3 min;95℃ 30 s,58℃ 30 s,72℃ 45 s,35个循环;72℃ 10 min,4 ℃保存。配制2%琼脂糖凝胶电泳检测PCR产物。条带明亮单一的DNA产物采用Illumina MiSeq二代高通量测序平台测定,测序长度2×300 bp (委托上海美吉生物医药科技有限公司完成)。

1.4 数据分析 数据下机后根据数据序列两端“标签”和引物序列得到有效序列,并使用FLASH和Trimmomatic软件进行去除片段大小不一致和拼接出现错配的序列;样品稀释性曲线[19]利用mothur计算不同随机抽样下的数值,使用R语言工具制作曲线图;使用Usearch软件(vsesion 7.1 http://drive5.com/uparse/)平台,按照94%相似性对非重复序列进行OTU聚类,在聚类过程中去除嵌合体,得到OTU的代表序列;通过GenBank中的非冗余核苷酸序列库(Non-redundant nucleotide sequences database, nt database)进行OTU注释,并分别在phylum (门),class (纲)和genus (属)分类水平统计各样品的群落组成;Alpha多样性指数运算,使用mothur软件[20](version v.1.30.1http://www.mothur.org/wiki/Schloss SOP#Alpha_diversity);物种Venn图[21]使用R语言统计和作图;非度量多维尺度分析[22](Nonmetric multidimensional scaling,NMDS)和样品层级聚类[23],使用Qiime计算beta多样性距离矩阵后,使用R语言作图画树。

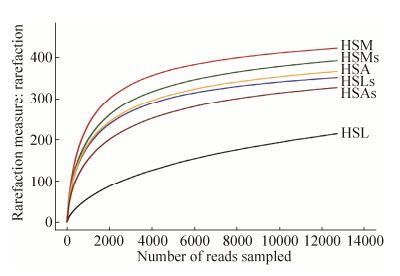

2 结果和分析 2.1 测序结果质量分析 通过对样品高通量数据统计,HSA、HSAs、HSL、HSLs、HSM和HSMs分别得到23604、31625、24940、23483、30375和32917条pufM基因序列,测序覆盖率均达到99%以上;稀释性曲线趋于平坦(图 1),表明测序结果能很好地代表各样品中AAPB群落结构和多样性。

|

| 图 1 高通量测序pufM基因序列稀释曲线 Figure 1 The rarefaction curves of pufM sequences obtained through HTS. |

| 图选项 |

2.2 AAPB群落结构分析 除去未分类部分,在门水平上,所有BSCs中的AAPB来自Proteobacteria、Chloroflexi和Actinobacteria 3大门类;Proteobacteria为优势门类,所有样品含量均在50%以上,其中HSL样品中含量最高,为94.43%,HSM中含量最低,为58.46%;HSAs中Chloroflexi含量最高,为1.80%,HSMs中含量最低,为0.07%;Actinobacteria含量极少。

在纲水平,主要包含Chloroflexia (HSMs中最低,为0.071%;HSAs中最高,为1.803%),Alpha-Proteobacteria (HSM中最低,为52.125%;HSL中最高,为93.687%)、Beta-Proteobacteria (HSL中最低,为0.205%;HSMs中最高,为1.322%)、Gamma-Proteobacteria (HSL中最低,为0.543%;HSLs中最高,为6.156%)及含量较少的Actinobacteria (HSA、HSL和HSM中为0;HSAs中最高,为0.126%)。

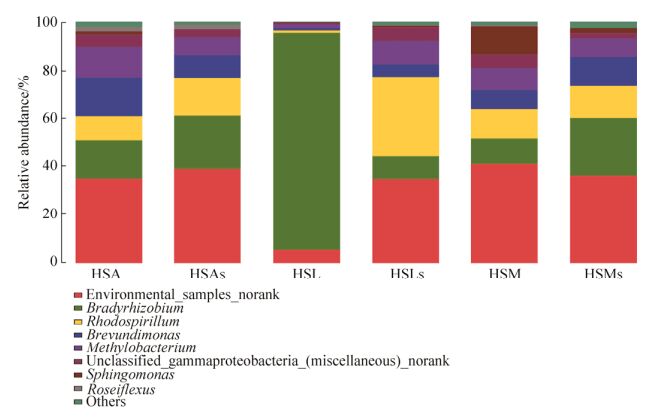

在属水平(图 2)上,除HSL样品以及未能分类的部分(35%以上的未知属)无法比较之外,结皮样品间及下层土壤样品间AAPB种类相似,都包含6个属,即Bradyrhizobium (9.69%–90.02%)、Brevundimonas (0.83%–16.04%)、Methylobacterium (1.74%–12.56%)、Rhodospirillum (0.91%–32.87%)、Roseiflexus (0.02%–1.79%)和Sphingomonas (0.13%–11.23%)。特别的是,Bradyrhizobium在HSL中的丰度高达90.02%、未知属不足10%;而更特别的是,unclassified_Gammaproteobacteria_ miscellaneous_norank几乎存在于每种类型样品中,丰度为0.47%–5.96%,在HSLs中最多。

|

| 图 2 AAPB在属水平的菌落结构及分布 Figure 2 Communities structure and distribution of AAPB at the genus level. |

| 图选项 |

NMDS是根据样品中包含的物种信息,以点的形式反映在多维空间上,而对不同样品间的差异程度,最终通过点与点的距离表现在图中。其距离远近代表样品中菌体群落的差异程度。由图 3-A可知,HSAs、HSLs和HSMs距离较近,AAPB群落差异较小;结皮层HSA和HSM中AAPB差异较小;而HSL则较为特殊,与其他样品差异较大。

|

| 图 3 非度量多维尺度分析图(A)和基于beta多样性距离的样品层级聚类树(B) Figure 3 Analysis of nonmetric multidimensional scaling (A) and hierarchical clustering tree based on the beta diversity of distance (B). |

| 图选项 |

通过对样品Beta多样性距离矩阵进行层级聚类分析,构建样品层级聚类树来研究不同样品的相似性和差异关系。聚类结果(图 3-B)同样表明3类结皮下层土壤样品差异较小、藻结皮层和苔藓结皮层差异小、地衣结皮层与其他样品差异较大的特点。

2.3 AAPB的Alpha多样性指数 Alpha多样性指数可反映生物群落的丰富度和多样性。其中,OTU能直接反映分类单元的数量,Shannon指数可以反映群落多样性,ACE指数则可以反映物种丰富度。由表 1可知,除HSL外,其他类型土壤中AAPB群落多样性指数较相近,OTU数、Shannon指数和ACE指数范围分别为157–238、4.04–4.92和373–448,最低和最高的均分别为HSAs和HSM,且均是上层高于相应下层指数,发育程度高的结皮及其对应下层土壤多样性指数也较高;HSL中虽然OTU数较少(157),Shannon指数较低(1.76),但物种丰富度却较高(402),且下层(HSLs)的OTU和Shannon指数均大于上层(HSL),但ACE指数的大小关系相反。由此可见,随结皮的发育,无论是结皮层还是其下层土壤中的AAPB种类都有所增加。

表 1. AAPB群落Alpha多样性指数 Table 1. Alpha diversity indexes of AAPB community

| Sample | Shannon index | ACE index |

| HSA | 4.43 | 399 |

| HSAs | 4.04 | 364 |

| HSL | 1.76 | 402 |

| HSLs | 4.37 | 373 |

| HSM | 4.92 | 448 |

| HSMs | 4.65 | 426 |

表选项

由图 4可知6个样品共有107个OTU,三类结皮层样品共有128个OTU,三类结皮样品下层土壤共有150个OTU;藻结皮及其下层土壤共有171个OTU,地衣结皮及其下层土壤共有138个OTU,苔藓结皮及其下层土壤共有194个OTU;HSA、HSAs、HSL、HSLs、HSM、HSMs中的特有OTU分别有1 (Hydrogenophaga sp. RAC07),1 (Roseateles depolymerans),2 (Skermanella stibiiresistens、Aquincola tertiaricarbonis),4 (Belnapia moabensis、Methylibium sp. Root1272、Kouleothrix aurantiaca、Polynucleobacter duraquae),13 (Methylibium sp. NZG、Sphingomonas sanxanigenens、Beta-proteobacterium AAP99、Sphingomonas sp. 031395428、Novosphingobium sp. AAP83、Methylobacterium sp. 77、Variovorax sp. KK3、Sphingomonas hengshuiensis、Sphingomonas sp. Leaf339、Bradyrhizobium sp. CCH5-F6、Methyloversatilis discipulorum、Sphingomonas sp. 031439814、Brevundimonas subvibrioides)和8个OTU(Mesorhizobium loti、Rhodocista sp. MIMtkB3、Rhizobacter sp. Root404、Bradyrhizobium sp. DFCI-1、Bradyrhizobium sp. S23321、Methyloversatilis sp. RAC08及2个未知OTU)。

|

| 图 4 样品中AAPB群落OTU水平Venn图 Figure 4 Venn diagram of AAPB communities in OTU. The number in the figures is the OTU amount. |

| 图选项 |

3 讨论 微生物群落结构和多样性分析研究中常用的方法有分离培养、梯度变性凝胶电泳和末端限制性片段长度多态性等。而近年来,随着测序分析技术的发展,高通量测序技术的应用愈来愈多。相比其他技术,高通量测序具有成本低和信息量大等优势。

好氧不产氧光营养细菌具有固氮或产多糖等功能,这些功能可能有助于土壤的形成和发展[12],尤其是在寡营养的陆生环境中的作用更加重要[24]。荒漠或沙地营养贫瘠,生物土壤结皮是这些环境中常见的重要景观;而在这些环境中,AAPB也可能有助于生物土壤结皮的发育。揭示BSCs中AAPB群落结构和多样性可为理解AAPB在BSCs发育中的作用提供基础依据。为此,本文基于pufM,利用高通量二代测序技术Mi-seq进行了相关分析。本研究表明各种类型或发育阶段的BSCs及其下层土壤中的AAPB皆以Proteobacteria为优势菌门、以Alpha-Proteobacteria为优势菌纲,这与Proteobacteria门的AAPB在其他的水生或陆生环境中占优势的情况相似[14, 16, 24-26]。但不同的是,淡水中没有Gamma-Proteobacteria,在盐水中缺乏Beta-Proteobacteria,而这两类却均在BSCs及其下层土壤中存在(Gamma-和Beta-Proteobacteria丰度分别为0.54%–6.16%和0.21%–1.32%)。张星星[27]基于16S rRNA基因分析荒漠BSCs时发现Chloroflexi门细菌占总细菌细胞数量的比例可达1%–7%。Chloroflexi门的AAPB在其他环境的好氧生态位中的丰度很低,而在本次基于pufM的分析调查表明其细胞数量可占总AAPB的约2%;但根据土壤中总AAPB数量占总细菌比例一般不足10%[4],估算本研究中Chloroflexi门的AAPB占总细菌数量的比例应低于0.2%。然而,目前明确含pufM的Chloroflexi细菌只有1个纯培养物[17],本研究所使用pufM通用引物可能只覆盖了Chloroflexi门中少数的AAPB菌群,这可能是基于pufM低于基于16S rRNA基因分析结果相差较大的原因。但结合二者可以肯定Chloroflexi门为BSCs中丰度较高的类群,其生理生态作用可能对于BSCs发育很重要。除地衣结皮外,藻结皮和苔藓结皮中AAPB的优势属(>5%)均为Bradyrhizobium、Brevundimonas、Methylobacterium、Rhodospirillum以及大量(>35%)未能分类的属。这不同于基于分离培养方法得到的Methylobacterium (60%)和Belnapla (27%)为BSCs中优势AAPB的结果[13],也不同于一般土壤中常见优势AAPB属为Crauroccus和Paracrauroccus,这2个属在BSCs中的丰度几乎为零。而地衣结皮中AAPB优势属为Bradyrhizobium,丰度高达90%,次优势的Methylobacterium和未能分类的属分别不足2%和6%。Bradyrhizobium可为地衣中与其共生生物提供氮素,有利于在寡营养环境中共生存[28];而可将光能作为辅助能源、减少有机碳消耗而使得AAPB在寡营养环境中更具竞争力[29]。因此,固氮和光营养可能是Bradyrhizobium在地衣结皮中大量存在的原因之一。而其余的优势分类类属Brevundimonas、Methylobacterium和Rhodospirillum都是或具有固氮、固碳或利用甲基化合物的能力。可见,具有光营养及其他营养利用或产生功能等很可能是微生物在荒漠寡营养土壤中生存的重要策略。比较结皮层及其下层土壤,除个别类群外,大多数在结皮层中丰度较高的类群往往在下层土壤中的丰度也高,且一般下层高于上层(最多可高14%)。这可能与强光抑制细菌叶绿素合成有关[30-31],也可能与AAPB主要吸收光波长为近红外[12]、近红外易穿透结皮层且为结皮中的蓝藻等所不能吸收有关。这可能决定了AAPB在结皮层和下层土壤中的分布不同。同时,结皮层中的AAPB利用蓝藻等不能利用的光,使光能利用更加充分,可能更加利于BSCs的发育。

BSCs及其下层土壤中AAPB的多样性非常高(除地衣结皮层Shannon指数只有1.76外,其他的为4.04–4.92),但丰富度较低(ACE指数最高为448)。这也明显不同于其他环境,例如在淡水和海水中AAPB的Shannon多样性指数都不超过3,而物种丰富度ACE指数却很高(最高高达6090)[16, 25-26]。而这与BSCs及下层土壤中AAPB群落结构揭示出的种类丰富、但以少数类属为主相一致。藻结皮、地衣结皮到苔藓结皮是BSCs发育过程中由低到高的3个阶段,发育愈成熟的BSCs愈发稳定[32]。生物多样性对于BSCs的多功能性作用发挥有重要影响[33]。除地衣结皮层外,BSCs及其相应下层土壤中AAPB多样性均随BSCs发育阶段的提高而增加,这或许预示着AAPB在荒漠生态系统稳定中有重要的作用。

4 结论 浑善达克沙地生物土壤结皮(Biological soil crusts, BSCs)中AAPB群落结构相对复杂,与水体和一般土壤环境中的组成区别明显;AAPB多样性高,且多样性随BSCs发育而增加,预示着AAPB在荒漠生态系统稳定中有重要的作用。

References

| [1] | Jiao NZ, Luo TW, Zhang Y, Zhang R, Tang K, Chen F, Zeng YH, Zhang YY, Zhao YL, Zheng Q, Li YL. Microbial carbon pump in the ocean——from microbial ecological process to carbon cycle mechanism. Journal of Xiamen University (Natural Science), 2011, 50(2): 387-401. (in Chinese) 焦念志, 骆庭伟, 张瑶, 张锐, 汤凯, 陈峰, 曾永辉, 张永雨, 赵艳琳, 郑强, 李彦玲. 海洋微型生物碳泵——从微型生物生态过程到碳循环机制效应. 厦门大学学报(自然科学版), 2011, 50(2): 387-401. |

| [2] | Chen XJ, Zeng YH, Jian JC, Lu YS, Wu ZH. Genetic diversity and quantification of aerobic anoxygenic phototrophic bacteria in Hugangyan Maar Lake based on pufM DNA and mRNA analysis. Microbiology China, 2012, 39(11): 1560-1572. (in Chinese) 陈晓洁, 曾永辉, 简纪常, 鲁义善, 吴灶和. 玛珥湖好氧不产氧光合细菌pufM基因DNA和mRNA的定量及多样性分析. 微生物学通报, 2012, 39(11): 1560-1572. |

| [3] | Jiang HC, Dong HL, Yu BS, Lü G, Deng SC, Wu YJ, Dai MH, Jiao NZ. Abundance and diversity of aerobic anoxygenic phototrophic bacteria in saline lakes on the Tibetan plateau. FEMS Microbiology Ecology, 2009, 67(2): 268-278. DOI:10.1111/fem.2009.67.issue-2 |

| [4] | Lew S, Lew M, Koblí?ek M. Influence of selected environmental factors on the abundance of aerobic anoxygenic phototrophs in peat-bog lakes. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 2016, 23(14): 13853-13863. DOI:10.1007/s11356-016-6521-8 |

| [5] | Yang SP, Lin ZH, Cui XH, Lian JK, Zhao CG, Qu YB. Current taxonomy of anoxygenic phototrophic bacteria-a review. Acta Microbiologica Sinica, 2008, 48(11): 1562-1566. (in Chinese) 杨素萍, 林志华, 崔小华, 连建科, 赵春贵, 曲音波. 不产氧光合细菌的分类学进展. 微生物学报, 2008, 48(11): 1562-1566. DOI:10.3321/j.issn:0001-6209.2008.11.023 |

| [6] | Belnap J, Weber B, Büdel B. Biological soil crusts as an organizing principle in drylands//Weber B, Büdel B, Belnap J. Biological Soil Crusts: An Organizing Principle in Drylands. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing, 2016: 3-13. |

| [7] | Jiao NZ, Sieracki ME, Zhang Y, Du HL. Aerobic anoxygenic phototrophic bacteria and their roles in marine ecosystems. Chinese Science Bulletin, 2003, 48(6): 530-534. (in Chinese) 焦念志, SierackiME, 张瑶, 杜海莲. 好氧不产氧光合异养细菌及其在海洋生态系统中的作用. 科学通报, 2003, 48(6): 530-534. |

| [8] | Wu N, Zhang YM, Pan HX, Qiu D. Culture-dependent bacteria diversity of lichen crusts in the Gurbantunggut Desert. Journal of Desert Research, 2013, 33(3): 710-716. (in Chinese) 吴楠, 张元明, 潘惠霞, 邱东. 古尔班通古特沙漠地衣结皮中可培养细菌多样性初探. 中国沙漠, 2013, 33(3): 710-716. DOI:10.7522/j.issn.1000-694X.2013.00102 |

| [9] | Colica G, De Philippis R. Exopolysaccharides from cyanobacteria and their possible industrial applications//Sharma NK, Rai AK, Stal LJ. Cyanobacteria: An Economic Perspective. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 2013: 197-207. |

| [10] | Bu CF, Wu SF, Xie YS, Zhang XC. The study of biological soil crusts:hotspots and prospects. Clean-Soil, Air, Water, 2013, 41(9): 899-906. DOI:10.1002/clen.v41.9 |

| [11] | Navarro-Noya YE, Jiménez-Aguilar A, Valenzuela-Encinas C, Alcántara-Hernández RJ, Ruíz-Valdiviezo VM, Ponce-Mendoza A, Luna-Guido M, Marsch R, Dendooven L. Bacterial communities in soil under moss and lichen-moss crusts. Geomicrobiology Journal, 2014, 31(2): 152-160. DOI:10.1080/01490451.2013.820236 |

| [12] | Yurkov V, Csotonyi JT. New light on aerobic anoxygenic phototrophs//Hunter CN, Daldal F, Thurnauer MC, Beatty JT. The Purple Phototrophic Bacteria. Dordrecht: Springer, 2009: 31-55. |

| [13] | Csotonyi JT, Swiderski J, Stackebrandt E, Yurkov V. A new environment for aerobic anoxygenic phototrophic bacteria:biological soil crusts. Environmental Microbiology Reports, 2010, 2(5): 651-656. DOI:10.1111/j.1758-2229.2010.00151.x |

| [14] | Koblí?ek M. Ecology of aerobic anoxygenic phototrophs in aquatic environments. FEMS Microbiology Reviews, 2015, 39(6): 854-870. DOI:10.1093/femsre/fuv032 |

| [15] | Waidner LA, Kirchman DL. Diversity and distribution of ecotypes of the aerobic anoxygenic phototrophy gene pufM in the Delaware estuary. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2008, 74(13): 4012-4021. DOI:10.1128/AEM.02324-07 |

| [16] | Ferrera I, Sarmento H, Priscu JC, Chiuchiolo A, González JM, Grossart HP. Diversity and distribution of freshwater aerobic anoxygenic phototrophic bacteria across a wide latitudinal gradient. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2017, 8: 175. |

| [17] | Zeng YH, Chen XH, Jiao NZ. Genetic diversity assessment of anoxygenic photosynthetic bacteria by distance-based grouping analysis of pufM sequences. Letters in Applied Microbiology, 2007, 45(6): 639-645. DOI:10.1111/lam.2007.45.issue-6 |

| [18] | Yutin N, Suzuki MT, Béjà O. Novel primers reveal wider diversity among marine aerobic anoxygenic phototrophs. Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2005, 71(12): 8958-8962. DOI:10.1128/AEM.71.12.8958-8962.2005 |

| [19] | Amato KR, Yeoman CJ, Kent A, Righini N, Carbonero F, Estrada AE, Gaskins HR, Stumpf RM, Yildirim S, Torralba M, Gillis M, Wilson BA, Nelson KE, White BA, Leigh SR. Habitat degradation impacts black howler monkey (Alouatta pigra) gastrointestinal microbiomes. The ISME Journal, 2013, 7(7): 1344-1353. DOI:10.1038/ismej.2013.16 |

| [20] | Schloss PD, Gevers D, Westcott SL. Reducing the effects of PCR amplification and sequencing artifacts on 16S rRNA-based studies. PLoS One, 2011, 6(12): e27310. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0027310 |

| [21] | Fouts DE, Szpakowski S, Purushe J, Torralba M, Waterman RC, MacNeil MD, Alexander LJ, Nelson KE. Next generation sequencing to define prokaryotic and fungal diversity in the bovine rumen. PLoS One, 2012, 7(11): e48289. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0048289 |

| [22] | Noval Rivas M, Burton OT, Wise P, Zhang YQ, Hobson SA, Garcia Lloret M, Chehoud C, Kuczynski J, DeSantis T, Warrington J, Hyde ER, Petrosino JF, Gerber GK, Bry L, Oettgen HC, Mazmanian SK, Chatila TA. A microbiota signature associated with experimental food allergy promotes allergic sensitization and anaphylaxis. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 2013, 131(1): 201-212. DOI:10.1016/j.jaci.2012.10.026 |

| [23] | Jiang XT, Peng X, Deng GH, Sheng HF, Wang Y, Zhou HW, Tam NFY. Illumina sequencing of 16S rRNA tag revealed spatial variations of bacterial communities in a mangrove wetland. Microbial Ecology, 2013, 66(1): 96-104. DOI:10.1007/s00248-013-0238-8 |

| [24] | Tahon G, Tytgat B, Stragier P, Willems A. Analysis of cbbL, nifH, and pufLM in soils from the S?r Rondane Mountains, Antarctica, reveals a large diversity of autotrophic and phototrophic bacteria. Microbial Ecology, 2016, 71(1): 131-149. DOI:10.1007/s00248-015-0704-6 |

| [25] | Zheng Q, Liu YT, Steindler L, Jiao NZ. Pyrosequencing analysis of aerobic anoxygenic phototrophic bacterial community structure in the oligotrophic western Pacific Ocean. FEMS Microbiology Letters, 2015, 362(8): fnv034. |

| [26] | Zhao BX, Liu Q, Zhao S, Wu CW. Analysis of aerobic anoxygenic phototrophic bacterial community structure in the different marine functional zones in the Zhoushan Archipelago Sea Area in summer. PeerJ Preprints, 2017, 5: e2820v1. |

| [27] | Zhang XX. Community structure and diversity of microorganism in biological soil crusts and underneath soil of Inner Mongolia deserts. Master's Thesis of Inner Mongolia Agricultural University, 2015. (in Chinese) |

| [28] | Seneviratne G, Indrasena IK. Nitrogen fixation in lichens is important for improved rock weathering. Journal of Biosciences, 2006, 31(5): 639-643. DOI:10.1007/BF02708416 |

| [29] | Soora M, Cypionka H. Light enhances survival of Dinoroseobacter shibae during long-term starvation. PLoS One, 2013, 8(12): e83960. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0083960 |

| [30] | Yurkov VV, Gemerden H. Impact of light/dark regimen on growth rate, biomass formation and bacteriochlorophyll synthesis in Erythromicrobium hydrolyticum. Archives of Microbiology, 1993, 159(1): 84-89. DOI:10.1007/BF00244268 |

| [31] | Lehours AC, Le Jeune AH, Aguer JP, Céréghino R, Corbara B, Kéraval B, Leroy C, Perrière F, Jeanthon C, Carrias JF. Unexpectedly high bacteriochlorophyll a concentrations in neotropical tank bromeliads. Environmental Microbiology Reports, 2016, 8(5): 689-698. DOI:10.1111/1758-2229.12426 |

| [32] | Zhang YM, Wang XQ. Summary on formation and developmental characteristics of biological soil crusts in desert areas. Acta Ecologica Sinica, 2010, 30(16): 4484-4492. (in Chinese) 张元明, 王雪芹. 荒漠地表生物土壤结皮形成与演替特征概述. 生态学报, 2010, 30(16): 4484-4492. |

| [33] | Bowker MA. Biological soil crust rehabilitation in theory and practice:an underexploited opportunity. Restoration Ecology, 2007, 15(1): 13-23. DOI:10.1111/rec.2007.15.issue-1 |