徐姗姗1,2, 闫思源1,2, 高权1,2, 姜学军1

1.中国科学院微生物研究所, 真菌学国家重点实验室, 北京 100101;

2.中国科学院大学, 北京 100039

收稿日期:2017-04-04;修回日期:2017-04-19;网络出版日期:2017-06-15

基金项目:国家自然科学基金(31371403)

*通信作者:姜学军, Tel:+86-10-64807728;Fax:+86-10-64807288;E-mail:jiangxj@im.ac.cn

摘要:[目的]明确真菌次级代谢产物rasfonin影响舒尼替尼(Sunitinib,ST)诱导的肾癌细胞自噬和凋亡作用机理。[方法]应用MTS(Methanethiosulfonate assay)和克隆形成实验检测rasfonin和舒尼替尼对肾癌细胞ACHN活性和增殖的影响,通过透射电子显微镜、荧光显微镜、蛋白免疫印迹、免疫荧光方法检测rasfonin和舒尼替尼处理的ACHN细胞自噬、凋亡情况和相关信号通路的变化。[结果]Rasfonin和舒尼替尼能够抑制肾癌细胞ACHN活性和细胞增殖;免疫印迹结果表明,两者均可以引起caspase依赖的凋亡。在rasfonin存在的情况下,不仅舒尼替尼所引起的凋亡和细胞活性丢失明显增加,而且其诱导的自噬流显著提高。无论是rasfonin还是舒尼替尼均明显地抑制哺乳雷帕霉素靶蛋白mTOR(Mammal target of rapamycin)磷酸化,而两者均能促进细胞外调节蛋白激酶(Extracellular regulated protein kinases,ERK)活性增加。[结论]rasfonin促进了舒尼替尼诱导的细胞自噬和凋亡,提高了舒尼替尼抑制肾癌细胞增殖的活性。

关键词: rasfonin 舒尼替尼 肾癌细胞 自噬 凋亡

Fungal secondary metabolite rasfonin enhances sunitinib-induced autophagy and apoptosis in renal carcinoma cells

Shanshan Xu1,2, Siyuan Yan1,2, Quan Gao1,2, Xuejun Jiang1

1.State Key Laboratory of Mycology, Institute of Microbiology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100101, China;

2.University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100039, China

Received 4 April 2017; Revised 19 April 2017; Published online 15 June 2017

*Corresponding author: Xuejun Jiang, Tel:+86-10-64807728;Fax:+86-10-64807288;E-mail:jiangxj@im.ac.cn

Supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31371403)

Abstract: [Objective]We studied the regulatory role of rasfonin in mediating sunitinib induced autophagy and apoptosis.[Methods]We used both methanethiosulfonate assay and colony growth assay to detect the cell viability and proliferation. In addition, we used electronic and fluorescence microscopy to examine the formation of autophagosome, as well as carried out immunofluorescence or immunoblotting to determine autophagy and apoptosis.[Results]Both rasfonin and sunitinib could induce autophagy and caspase-dependent apoptosis in renal carcinoma cells. Notably, low dose of rasfonin enhanced sunitinib-dependent autophagy and apoptosis, meanwhile sunitinib and rasfonin synergistically inhibited cell viability. In addition, both sunitinib and rasfonin inhibited the phosphorylation of mammal target of rapamycin and increased the activity of extracellular regulated protein kinases.[Conclusion]Rasfonin promotes sunitinib-induced autophagy and caspase dependent apoptosis, and strengthens the cytotoxic effect of sunitinib in renal carcinoma cells.

Key words: rasfonin sunitinib renal cancer cell autophagy apoptosis

肾癌是泌尿系统常见的疾病[1]。由于肾脏位于腹膜后,所以早期发现肾癌一直是泌尿外科的难题之一。因其邻近大血管,使得肾癌更容易发生早期转移,且该肿瘤对放、化疗均不敏感,从而导致其术后五年存活率很低[2]。针对肾癌开展靶向治疗以及寻找新的靶向治疗药物一直是临床上的研究热点之一。

舒尼替尼是多靶点受体酪氨酸激酶抑制剂,在欧洲泌尿外科学会颁布的肾癌诊疗指南中被认证为晚期肾癌的一线治疗药物[3],通过拮抗肾癌细胞内血管内皮生长因子受体和血小板衍生内皮生长因子受体等多种受体酪氨酸激酶活性,同时抑制肿瘤和肿瘤内新生血管生长[4]。目前有关舒尼替尼调节细胞自噬存在着相互矛盾的地方,如在膀胱肿瘤中,舒尼替尼处理24 h引起自噬依赖性细胞坏死[5],而在肾癌中自噬抑制剂氯喹促进舒尼替尼诱导细胞死亡[6],还有其他肿瘤细胞中,抑制自噬增强舒尼替尼的细胞毒性作用[7]。因此舒尼替尼对自噬的调节还有很多不明之处。

细胞自噬是真核生物中普遍存在的现象,用于降解长寿命蛋白和细胞器[8]。其参与多种生理、病理过程,在肿瘤细胞中也存在着双向作用。根据降解底物转运至溶酶体的方式不同,细胞自噬可分为大自噬、小自噬和分子伴侣型自噬[9]。通常意义上讲的自噬是指的细胞大自噬。尽管最初发现自噬有利于细胞在应急状态下的存活,但是过度的自噬会导致自噬性细胞死亡,也称其为二类程序性细胞死亡。目前普遍认为程序性细胞死亡(Programmed cell death,PCD)可分为3类:细胞凋亡、自噬性细胞死亡和程序性坏死[10-11]。细胞凋亡,又称I型程序性细胞死亡,由内源途径和外源途径通过激活半胱天冬酶(Caspase)蛋白家族级联反应诱导发生,形态学特征表现为染色质浓缩、细胞皱缩、与邻近细胞脱离、晚期可见凋亡小体[12]。自噬与凋亡的形态学特征和调控方式具有显著的区别,但是越来越多的研究发现,自噬和凋亡具有密切联系[13-14]。一方面,自噬为凋亡过程提供能量,保障凋亡顺利进行[15-16];另一方面,自噬又可作为保护机制,抑制细胞凋亡[17]。

细胞自噬受多条信号通路严格调控。mTOR是丝氨酸/酪氨酸蛋白激酶,属于磷脂酰肌醇激酶相关激酶(Phosphatidylinositol kinase-related kinase,PIKK)蛋白家族[18-19]。一般认为,mTOR通过抑制ULK1 (Unc-51-like kinase)的激酶活性,负调控细胞自噬[20]。胞外信号调节激酶是促分裂原活化蛋白激酶(Mitogen activated protein kinase,MAPK)家族成员。在多种细胞系中,激活的ERK诱导自噬发生。K562细胞中ERK通过自噬相关蛋白Beclin 1 (Atg6)正调控自噬[21]。此外,有研究报道在宫颈癌细胞HeLa中,伴刀豆球蛋白A (Concanavalin A,Con A)通过抑制mTOR和上调ERK信号通路诱导自噬[22]。

Rasfonin是从Talaromyces sp. 3656-A1发酵液分离得到的真菌次级代谢产物,属于2-吡喃酮类化合物,因其抑制小G蛋白Ras的活性而得名。有研究报道称,rasfonin能够诱导Ras突变的胰腺肿瘤细胞死亡[23]。我们之前的研究表明,rasfonin可以诱导肾癌细胞的多种死亡方式,而抑制自噬减少了rasfonin诱导的细胞凋亡[24]。尽管如此,有关rasfonin联合应用舒尼替尼影响肾癌细胞增殖、自噬以及凋亡的研究还未见报道。本研究联合rasfonin和舒尼替尼处理肾癌细胞系ACHN,观察其发生自噬、凋亡以及自身的增殖情况,以期通过此项研究更好地了解自噬诱导的分子机制,并为今后可能的临床应用提供理论基础。

1 材料和方法 1.1 材料

1.1.1 细胞系: ACHN细胞为本实验室保存。

1.1.2 药品和抗体: Rasfonin由军事医学科学院车永胜研究员提供。舒尼替尼购自美国辉瑞公司;氯喹(Chloroquine diphosphate salt,CQ)和多克隆抗体LC3B购自Sigma公司;actin抗体购自北京中杉金桥公司;p62/SQSTM1 (Sequestosome 1,p62)抗体购自Santa Cruz公司;pmTOR (S2448)、mTOR、pErk1/2 (T202/Y204)和tErk1/2抗体购自Cell Signaling Technology公司。

1.1.3 试剂和耗材: DMEM培养基和胎牛血清购自Gibco公司;青链霉素混合液和胰蛋白酶消化液购自南京凯基生物科技发展有限公司;PVDF膜购于Amersham公司;发光液购自Thermo公司。

1.1.4 仪器设备: CO2细胞培养箱(Panasonic SANYO公司)、台式高速离心机(Sigma公司)、-20 ℃低温冰箱(海尔公司)、-80 ℃低温冰箱(Heraeus公司)、Trans-Blot电转仪(Bio-RAD公司)、AE-6500型电泳槽(ATTO公司)、JY600C恒压恒流电泳仪(JUNYI公司)、MilliQ plus超纯水系统(Millipore公司)、Biospec-nano UV-VIS分光光度计(日本岛津公司)、化学发光成像仪Tanon 5200 (天能公司)。

1.2 细胞培养 ACHN细胞系使用DMEM High Glucose (含10%的胎牛血清、1%的青链双抗)培养,置于37 ℃、5% CO2细胞培养箱中培养,当细胞密度达到完全汇合的70%时传代。

1.3 药物处理和细胞收集 将细胞接种到6孔板内,37 ℃、5% CO2细胞培养箱中培养过夜,至细胞汇合度达到60%-70%时加入药物进行刺激,待指定时间后收集细胞。

待细胞到指定处理时间后,用冷的PBS漂洗细胞1次,弃去PBS,用TGH裂解液刮取细胞[TGH的组成:1 mL母液(1% Triton X-100,10%甘油,50 mmol/L Hepes,pH 7.4),5 mol/L NaCl 20 μL,0.5 mol/L EGTA/EDTA 10 μL,0.1 mol/L NaF 10 μL,0.1 mol/L PMSF 20 μL,1 mol/L DTT 2 μL,0.5 mol/L Na3VO4 2 μL,Protease inhibitor 1 μL。加入一半体积的3×loading buffer,96 ℃加热30 min后,室温离心(13000 r/min,15 min),上清即为全细胞裂解液。

1.4 免疫荧光 ACHN细胞接种于放有盖玻片的6孔板中,37 ℃、5% CO2细胞培养箱中培养过夜。药物处理预定时间后,预冷的PBS洗去残余培养基。4%多聚甲醛溶液固定15 min,预冷PBS洗3遍,每次5 min。一抗以1:100稀释于含0.1% Triton X-100和0.5% BSA的PBS,盖玻片浸润一抗溶液,孵育1 h。孵育结束后,预冷PBS洗3遍,每次5 min。二抗(Alexa Fluor? 594 Goat anti-Rabbit)以1:100稀释于含0.5% BSA的PBS,盖玻片浸润二抗溶液,孵育1 h。预冷PBS洗涤3遍。盖玻片浸润VECTASHIELD with DAPI核酸染料染色,封片后在荧光显微镜下观察。

1.5 电镜样品的制备 将ACHN细胞接种6 cm培养皿中,37 ℃、5% CO2细胞培养箱中培养过夜,至细胞汇合度达到60%-70%。药物处理指定时间后,胰酶消化细胞,4 ℃、1000×g离心5 min收集细胞,冷PBS洗涤2遍。缓慢加入3%戊二醛,4 ℃固定过夜,使用二甲基胂酸盐缓冲液配制的1% OsO4室温固定1 h,随后用乙醇做脱水处理,之后用环氧丙烷漂洗,最后将样品包埋于树脂中,切片观察。

1.6 免疫印迹检测 相同生长密度细胞经目的药物处理,待指定处理时间后,制备全细胞裂解液电泳样品。等量全细胞裂解液样品经过8%-15% SDS-PAGE分离蛋白,转膜至PVDF膜上,PVDF膜用5%脱脂奶粉封闭液室温封闭1 h,加入相应要检测的蛋白一抗4 ℃孵育过夜,回收一抗后适当TBST漂洗,二抗(一抗相对应的鼠抗或者兔抗)室温孵育1 h,将漂洗后的PVDF膜放在大小合适的保鲜膜上,在膜上加发光液,放入暗盒中,将X光片压于膜上,适当时间后洗片,或直接在化学成像仪中曝光获取图像。根据记录结果,进行灰度值计算。

1.7 MTS细胞活性检测实验 将5000-10000个细胞分至96孔板中,每孔体积为100 μL。过夜后换为新鲜的无酚红DMEM培养基(含10%胎牛血清),并加入不同浓度的药物处理。加入20 μL MTS/PMS (MTS:PMS=20:1),37 ℃、5% CO2条件下持续培养,4 h内检测,酶标仪测定波长490 nm处的吸光度值,每个样品设置3次平行重复。

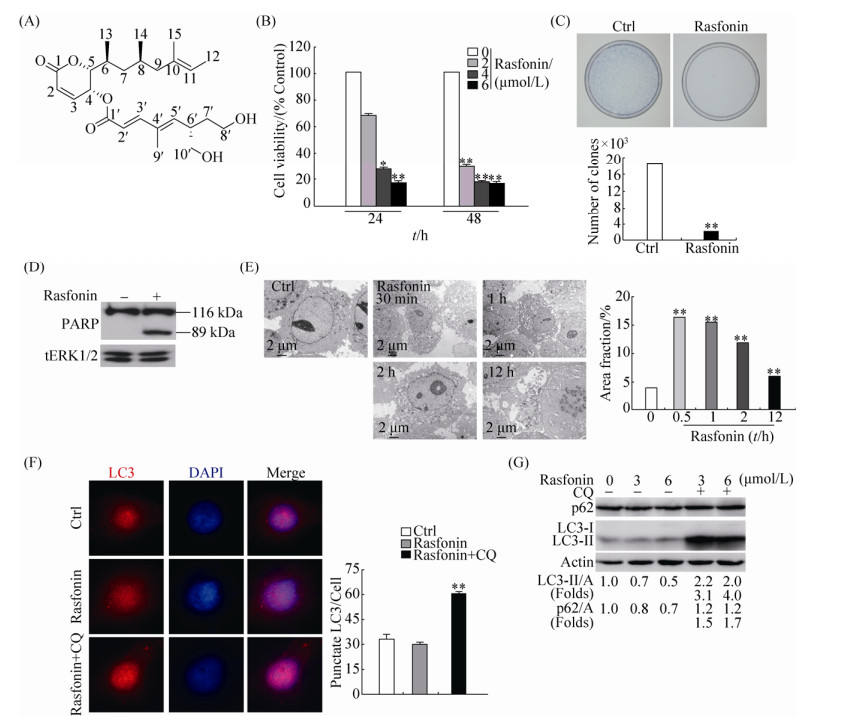

2 结果和分析 2.1 Rasfonin抑制肾癌细胞活性并诱导细胞自噬 Rasfonin是从Talaromyces sp. 3656-A1发酵液中分离得到的真菌次级代谢产物(图 1-A)。MTS是常用的检测细胞活性的方法。利用MTS我们发现,rasfonin处理ACHN细胞24 h和48 h,细胞活性随着浓度增加而减少(图 1-B)。克隆形成实验能直观反映细胞增殖能力,常用于检测化合物对肿瘤的抑制。从图 1-C中可以看出,rasfonin能明显地抑制ACHN细胞的克隆形成,说明该化合物具有较强的抑制肿瘤细胞增殖的能力(图 1-C)。多聚ADP核糖聚合酶(Poly ADP-ribose polymerase,PARP-1)是真核细胞中普遍存在的多功能蛋白质翻译后修饰酶,在细胞凋亡发生时,核心成员半胱天冬酶(Caspase)可以使PARP-1片段化,使其失去酶活性,因此PARP-1作为标记蛋白被广泛应用于检测caspase依赖性的细胞凋亡。免疫印迹检测结果表明,rasfonin处理能引起PARP-1切割,说明该化合物诱导ACHN细胞发生caspase依赖性细胞凋亡(图 1-D)。通常情况下,细胞自噬发生时间早于细胞凋亡,且在细胞凋亡过程中发挥促进作用。因此我们检测了rasfonin短时间刺激时ACHN细胞内自噬发生情况。透射电子显微镜是检测自噬体最直观的方法。电镜结果显示,rasfonin刺激30 min、1 h和2 h后,ACHN细胞中泡状结构(自噬体/自噬溶酶体)的数量明显增加。而处理12 h,图 1-E中虽然自噬体/自噬溶酶体的数量略有下降,但我们观察到ACHN细胞发生凋亡,说明rasfonin诱导的自噬早于凋亡的发生。微管相关蛋白1轻链3 (Microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3,LC3)脂化后结合自噬体膜,与底物一起被溶酶体降解,是普遍使用的自噬标记蛋白[25]。氯喹(Chloroquine,CQ)因其改变溶酶体pH值从而阻断自噬体和溶酶体结合,是常用的检测自噬流的化合物[26]。LC3通常情况下呈弥散分布,当受到自噬刺激时,其发生聚集并呈点状,可以反映LC3-Ⅱ和自噬体的量。通过免疫荧光我们发现,对照组LC3点数较少,说明基础自噬水平较低。尽管rasfonin单独处理后LC3点数减少,但是CQ存在明显增加了LC3点数,说明rasfonin促进自噬流(图 1-F)。免疫杂交结果表明,CQ能阻断rasfonin处理后LC3-Ⅱ的降低。相比较单独rasfonin处理,rasfonin和CQ共同处理使LC3-Ⅱ的量明显上升。由于自噬是动态变化过程,自噬体膜上结合的LC3-Ⅱ被不断降解,因此单独rasfonin处理时LC3-Ⅱ的降解加速,含量降低。SQSTM 1 (Sequestosome 1,p62)是多功能泛素结合蛋白,可以与LC3直接结合,常被作为自噬底物和自噬流的标记进行检测[27]。在自噬发生时,其含量会减少。与LC3-Ⅱ的变化类似,rasfonin处理降低了p62含量,而CQ能抑制p62的降解(图 1-G)。上述结果表明rasfonin确能诱导肾癌细胞发生自噬。

|

| 图 1 Rasfonin诱导ACHN细胞活性丢失和自噬 Figure 1 Rasfonin induces autophagy and decreases cell viability in ACHN cells. A: The chemical structure of rasfonin. B: ACHN cells were treated with rasfonin (2–6 μmol/L) upon to 48 h. Cell viability was analysed by methanethiosulfonate (MTS) assay as described in Materials and Methods. C: Colony growth assays were performed following the treatment with rasfonin (1 μmol/L) for 14 d. Data represent the mean±SD of three experiments, each performed in triplicate. D: ACHN cells were treated with rasfonin (6 μmol) for 12 h and cell lysates were prepared and analysed by immunoblotting using the indicated antibodies, tErk1/2 (total Erk1/2) was used as loading control. Densitometry was performed for quantification and relative ratios of cleaved PARP (cPARP) were shown below the blots. E: Electron microscopy was utilized to detect the vacuoles in ACHN cells following challenge rasfonin (6 μmol/L) for indicated time. F: Immunofluorescence was performed using the LC3 antibody following rasfonin (6 μmol/L) in the presence or absence of CQ (15 μmol/L) for 2 h. G: ACHN cells were treated with rasfonin (3 μmol/L or 6 μmol/L) for 2 h in the presence or absence of CQ (15 μmol/L). The lysates of the cells were analysed by immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies. Actin (A) was used as loading control. The ratio of LC3 and p62 to actin were showed below the blots. Similar experiments repeated three times. For histogram results, the data were presented as mean±S.D. and analyzed by T-test. *: P < 0.05 vs. control; **: P < 0.01 vs. control. |

| 图选项 |

2.2 舒尼替尼抑制ACHN细胞活性并诱导自噬 舒尼替尼是临床治疗晚期肾癌的一线药物。MTS实验结果表明,肾癌细胞ACHN经舒尼替尼处理24 h和48 h后,细胞活性明显下降,且舒尼替尼抑制作用具有浓度依赖性(图 2-A)。克隆形成实验证实,舒尼替尼刺激导致ACHN细胞克隆数目明显减少,细胞增殖被抑制(图 2-B)。免疫印迹结果显示,舒尼替尼诱导ACHN细胞中PARP-1切割,说明舒尼替尼能诱导细胞发生caspase依赖性的凋亡(图 2-C)。利用透射电子显微镜我们观察到舒尼替尼处理后,与对照组相比,ACHN细胞自噬体/自噬溶酶体明显增加(图 2-D)。免疫荧光结果也显示,舒尼替尼刺激后LC3点数染色增加,舒尼替尼与CQ共同处理时LC3点数进一步增加(图 2-E)。通过免疫印迹我们观察到,与rasfonin刺激不同,舒尼替尼处理增加LC3-Ⅱ蛋白含量,而减少p62蛋白水平。在CQ存在的情况下,舒尼替尼引起的LC3-Ⅱ和p62含量进一步增加(图 2-F)。这些结果表明,舒尼替尼能增加肾癌细胞的自噬水平和引起caspase依赖性细胞凋亡并抑制细胞增殖。

|

| 图 2 舒尼替尼诱导ACHN细胞活性丢失和自噬 Figure 2 ST activates autophagy and inhibits cell viability in ACHN cells. A: ACHN cells were treated with ST with the concentration from 2 μmol/L to 8 μmol/L for 24 h and 48 h. Cell viability was analysed by methanethiosulfonate (MTS) assay as described in Materials and Methods. B: Colony survival assays in ACHN cells were performed following the treatment with 2 μmol/L ST for 14 d. Data represent the mean±SD of three experiments, each performed in triplicate. C: ACHN cells were treated with ST (8 μmol/L) for 12 h and cell lysates were prepared and analysed by immunoblotting using the indicated antibodies, tERK1/2 was used as loading control. Densitometry was performed for quantification and relative ratios of cleaved PARP (cPARP) were shown below the blots. D: Electron microscopy was used to detect the vacuoles in ACHN cells in the medium of ST (8 μmol/L) for indicated time. E: Immunofluorescence was performed using the LC3 antibody in ACHN cells following ST (8 μmol/L) with or without CQ (15 μmol/L) for 2 h. F: ACHN cells were treated with ST (2 μmol/L or 8 μmol/L) for 2 h in the presence or absence of CQ (15 μmol/L). The lysates of the cells were analysed by western blotting with the indicated antibodies. Actin (A) was used as loading control. The ratio of LC3 and p62 to Actin were showed under the blots. Similar experiments repeated three times. For histogram results, the data were presented as mean±S.D. and analyzed by T-test. *: P < 0.05 vs. control; **: P < 0.01 vs. control. |

| 图选项 |

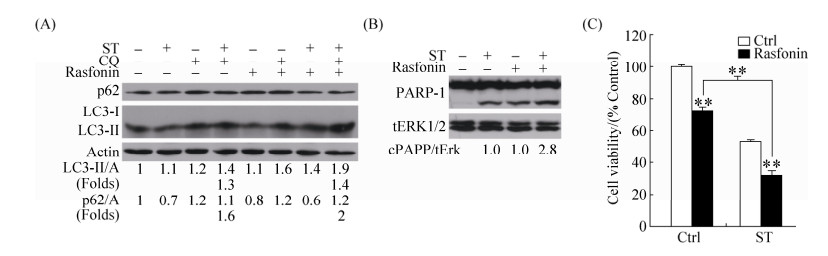

2.3 Rasfonin促进舒尼替尼诱导的自噬和凋亡 Rasfonin和舒尼替尼均能诱导ACHN细胞中自噬发生,为了验证二者是否具有协同作用,我们利用免疫杂交检测了rasfonin与舒尼替尼共同处理时ACHN细胞中自噬流的变化情况。从图 3-A可以看出,rasfonin与舒尼替尼共同处理时的LC3-Ⅱ的蛋白含量明显高于单独舒尼替尼处理组,CQ存在情况下,LC3-Ⅱ蛋白含量进一步增加,因此rasfonin明显上调舒尼替尼诱导的自噬流(图 3-A)。同时,rasfonin能明显增强舒尼替尼引起的PARP-1切割(图 3-B)。此外,MTS检测细胞活性发现,rasfonin与舒尼替尼共同处理组的ACHN细胞活性明显低于单独舒尼替尼处理组(图 3-C)。上述结果表明,rasfonin增强舒尼替尼诱导的自噬和caspase依赖性细胞凋亡,促进舒尼替尼引起的活性丢失。

|

| 图 3 Rasfonin促进舒尼替尼诱导的ACHN细胞自噬和活性丢失 Figure 3 Rasfonin promotes ST-induced autophagy and apoptosis concurring with an increased inhibiiton on cell viability. A: ACHN cells were treated with rasfonin (6 μmol/L) plus ST (8 μmol/L) for 2 h in the presence or absence of CQ (15 μmol/L). The lysates of the cells were analysed by Western blotting with the indicated antibodies. Actin (A) was used as loading control. The ratio of LC3 and p62 to actin were showed under the blots. B: ACHN cells were treated with ST (8 μmol/L) in the presence or absence of rasfonin (6 μmol/L) for 12 h and cell lysates were prepared and analysed by immunoblotting using the indicated antibodies, tERK1/2 (total Erk1/2) was used as loading control. Densitometry was performed for quantification and relative ratios of cleaved PARP (cPARP) were shown below the blots. C: ACHN cells were treated with ST (8 μmol/L) with or without rasfonin the concentration (6 μmol/L) upon to 48 h. Cell viability was analysed by methanethiosulfonate (MTS) assay as described in Materials and Methods. Similar experiments repeated three times. For histogram results, the data were presented as mean±S.D. and analyzed by T-test. *: P < 0.05 vs. control; **: P < 0.01 vs. control. |

| 图选项 |

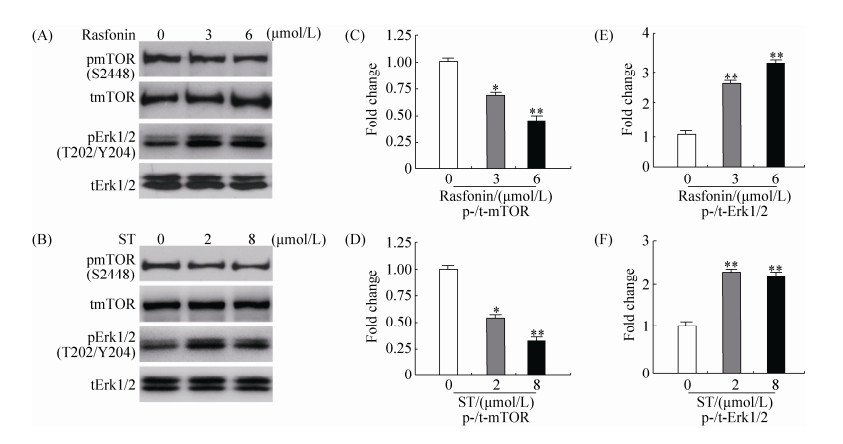

2.4 Rasfonin抑制mTOR磷酸化并促进ERK磷酸化 为了研究rasfonin和舒尼替尼诱导ACHN细胞自噬的机理,我们通过免疫杂交实验检测了细胞自噬相关信号通路蛋白的含量(图 4-A和4-B)。结果显示,不同浓度rasfonin和舒尼替尼处理后,mTOR磷酸化水平被抑制(图 4-C和4-D),而Erk1/2磷酸化水平明显上升(图 4-E和4-F)。并且rasfonin和舒尼替尼对信号蛋白磷酸化水平的影响,也具有浓度依赖性。因此我们推测,rasfonin和舒尼替尼通过抑制mTOR信号通路并促进Erk1/2信号通路诱导自噬。

|

| 图 4 Rasfonin和舒尼替尼抑制mTOR磷酸化并上调ERK磷酸化 Figure 4 Rasfonin and ST inhibit the phosphorylation of mTOR and increase the level of phosphorylated Erk1/2. A: ACHN cells were treated with rasfonin (3 μmol/L or 6 μmol/L) for 2 h. The lysates of the cells were analyzed by immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies. C and E: Densitometry was performed for quantification and relative ratios of phosphorylated mTOR and Erk1/2 were shown in graphs. Similar experiments repeated three times. B: ACHN cells were treated with ST (2 μmol/L or 8 μmol/L) for 2 h. The lysates of the cells were analysed by Western blotting with the indicated antibodies. D and F: Densitometry was performed for quantification and relative ratios of phosphorylated mTOR and Erk1/2 were shown in graphs. Similar experiments repeated three times. For histogram results, the data were presented as mean±S.D. and analyzed by T-test. *: P < 0.05 vs. control; **: P < 0.01 vs. control. |

| 图选项 |

3 讨论 在该研究中,我们首次将真菌次级代谢产物rasfonin与临床治疗肾癌药物舒尼替尼联合使用并进行有关细胞自噬和凋亡的研究工作,并发现rasfonin不仅能促进舒尼替尼诱导的细胞自噬,而且能增加后者诱导的细胞凋亡。我们之前的研究发现rasfonin诱导肾癌细胞发生多种死亡方式[24],但rasfonin和舒尼替尼共同处理对肾癌细胞活性、自噬及凋亡的影响还未见报道。本研究发现rasfonin和舒尼替尼通过抑制mTOR和激活ERK信号通路来诱导肾癌细胞自噬。由于舒尼替尼在临床应用过程中会发生抗药性和毒副作用,因此,我们期望通过此类研究能改善舒尼替尼类药物的临床应用效果,也为从真菌次级代谢产物中筛选可用于临床治疗的药物提供理论基础。

自噬是动态变化过程,不仅仅是自噬体的形成,还包括自噬体的降解及底物分子在自噬过程中的传递。自噬体降解过程的减慢与自噬过程的诱导一样,也能引起LC3-Ⅱ的积累,而在这种情况下,底物分子不能正常降解,反映的是自噬被抑制的过程。而LC3-Ⅱ水平的降低可能是由于自噬流的增加,从而导致形成的LC3-Ⅱ被快速降解,但这并不能代表自噬的减少。所以不能仅凭加药处理后LC3-Ⅱ的增减来判断自噬的发生水平[28],目前普遍通过检测自噬流研究细胞内自噬发生情况[29]。氯喹(CQ)等自噬-溶酶体融合的抑制剂可以阻断LC3-Ⅱ降解,从而提高LC3-Ⅱ的水平。此时LC3-Ⅱ相比于单独处理时LC3-Ⅱ的增加倍数(Fold值)能很好地反映细胞中的自噬流[30]。本研究中,虽然在单独加rasfonin时LC3-Ⅱ蛋白水平下降而单独加舒尼替尼LC3-Ⅱ水平上升,但是在CQ存在情况下,两种处理均导致LC3-Ⅱ的水平均明显进一步上升,说明在rasfonin处理的细胞中,自噬流的加快使得LC3-Ⅱ的水平没有升高,反映的仍是一个诱发自噬的过程。舒尼替尼处理后的细胞中,自噬体形成和自噬流均增加。另一方面,自噬的底物p62在rasfonin和舒尼替尼处理后,含量均明显下降。而自噬被CQ阻断后,p62含量上升,说明两种药物都能引起p62的自噬性降解。因此rasfonin和舒尼替尼均诱导自噬发生。而单独rasfonin和舒尼替尼处理后,LC3-Ⅱ蛋白水平变化不一致,可能是由于自噬体降解速率不相同导致。

舒尼替尼在临床肾癌靶向治疗中具有重要地位,治疗效果优于其他抗肿瘤药物如干扰素α和帕唑帕尼[31-32]。舒尼替尼不仅抑制肾癌细胞生长,还能诱导肾癌细胞凋亡[33]。但也有研究报道,转移性肾细胞瘤对舒尼替尼具有耐药性,耐药性与舒尼替尼诱导的细胞自噬有关[34]。抑制Akt/mTOR信号通路抑制自噬后,肾癌细胞和前列腺癌细胞对舒尼替尼处理更敏感,耐受性降低[35]。本研究发现,舒尼替尼上调ACHN细胞中ERK磷酸化水平,而活化的ERK信号通路正调控细胞生长增殖。因此我们推测,舒尼替尼诱导细胞自噬和ERK信号通路激活是肾癌细胞产生耐药性的原因。

近年来多项研究报道,联合用药可增强舒尼替尼对肿瘤细胞活性的抑制作用。对肾癌病人的治疗研究发现,贝伐单抗增强舒尼替尼的治疗效果,但药理学原理并不清楚[36]。舒尼替尼和紫杉醇治疗晚期乳腺癌预后效果良好,且没有药物-药物联合反应[37]。特定剂量的舒尼替尼和埃罗替尼对非小细胞肺癌的治疗效果较好[38]。这些研究结果提示我们,其他化合物可以增强舒尼替尼的肿瘤治疗效果。本研究发现真菌次级代谢产物rasfonin通过增强舒尼替尼诱导的肾癌细胞自噬和凋亡,增强其对肿瘤活性的抑制作用。这既是对联合用药效果增强机制的探讨,也可为从真菌次级代谢产物库中筛选具有抗肿瘤活性的化合物提供新思路。

Rasfonin诱导ACHN细胞自噬的机理研究已有报道,与之不同的是本研究新发现了rasfonin通过促进ERK磷酸化来诱导自噬,因此,我们推测该化合物能影响多种信号通路。由于其能抑制mTOR信号通路,而后者的抑制剂雷帕霉素也已经用于临床肾癌的治疗[39]。这样有理由相信,对rasfonin的深入研究,不仅能更好地认识自噬调节机制以及不同死亡方式之间的内在联系,也能为临床筛选新的药物进行肿瘤治疗提供新靶点。

致谢: 衷心感谢军事医学科学院车永胜研究员提供的真菌次级代谢产物rasfonin!

References

| [1] | St?rkel S, Eble JN, Adlakha K, Amin M, Blute ML, Bostwick DG, Darson M, Delahunt B, Iczkowski K. Classification of renal cell carcinoma:Workgroup No. 1. Union Internationale Contre le Cancer (UICC) and the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC). Cancer, 1997, 80(5): 987-989. DOI:10.1002/(ISSN)1097-0142 |

| [2] | Ljungberg B, Cowan NC, Hanbury DC, Hora M, Kuczyk MA, Merseburger AS, Patard JJ, Mulders PFA, Sinescu IC. EAU guidelines on renal cell carcinoma:the 2010 update. European Urology, 2010, 58(3): 398-406. DOI:10.1016/j.eururo.2010.06.032 |

| [3] | Goodman VL, Rock EP, Dagher R, Ramchandani RP, Abraham S, Gobburu JVS, Booth BP, Verbois SL, Morse DE, Liang CY, Chidambaram N, Jiang JX, Tang SH, Mahjoob K, Justice R, Pazdur R. Approval summary:sunitinib for the treatment of imatinib refractory or intolerant gastrointestinal stromal tumors and advanced renal cell carcinoma. Clinical Cancer Research, 2007, 13(5): 1367-1373. DOI:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2328 |

| [4] | Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Tomczak P, Michaelson MD, Bukowski RM, Oudard S, Negrier S, Szczylik C, Pili R, Bjarnason GA, Garcia-del-Muro X, Sosman JA, Solska E, Wilding G, Thompson JA, Kim ST, Chen I, Huang X, Figlin RA. Overall survival and updated results for sunitinib compared with interferon alfa in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 2009, 27(22): 3584-3590. DOI:10.1200/JCO.2008.20.1293 |

| [5] | Santoni M, Amantini C, Morelli MB, Liberati S, Farfariello V, Nabissi M, Bonfili L, Eleuteri AM, Mozzicafreddo M, Burattini L, Berardi R, Cascinu S, Santoni G. Pazopanib and sunitinib trigger autophagic and non-autophagic death of bladder tumour cells. British Journal of Cancer, 2013, 109(4): 1040-1050. DOI:10.1038/bjc.2013.420 |

| [6] | Abdel-Aziz AK, Shouman S, El-Demerdash E, Elgendy M, Abdel-Naim AB. Chloroquine synergizes sunitinib cytotoxicity via modulating autophagic, apoptotic and angiogenic machineries. Chemico-Biological Interactions, 2014, 217: 28-40. DOI:10.1016/j.cbi.2014.04.007 |

| [7] | Pan XH, Zhang XL, Sun HL, Zhang JJ, Yan MM, Zhang HB. Autophagy inhibition promotes 5-fluorouraci-induced apoptosis by stimulating ROS formation in human non-small cell lung cancer A549 cells. PLoS One, 2013, 8(2): e56679. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0056679 |

| [8] | Lee MJ, Lee JH, Rubinsztein DC. Tau degradation:the ubiquitin-proteasome system versus the autophagy-lysosome system. Progress in Neurobiology, 2013, 105: 49-59. DOI:10.1016/j.pneurobio.2013.03.001 |

| [9] | Bejarano E, Cuervo AM. Chaperone-mediated autophagy. Proceedings of the American Thoracic Society, 2010, 7(1): 29-39. DOI:10.1513/pats.200909-102JS |

| [10] | Lockshin RA. Programmed cell death:history and future of a concept. Journal de la Société de Biologie, 2005, 199(3): 169-173. DOI:10.1051/jbio:2005017 |

| [11] | Ouyang L, Shi Z, Zhao S, Wang FT, Zhou TT, Liu B, Bao JK. Programmed cell death pathways in cancer:a review of apoptosis, autophagy and programmed necrosis. Cell Proliferation, 2012, 45(6): 487-498. DOI:10.1111/cpr.2012.45.issue-6 |

| [12] | Elmore S. Apoptosis:a review of programmed cell death. Toxicologic Pathology, 2007, 35(4): 495-516. DOI:10.1080/01926230701320337 |

| [13] | Su MF, Mei Y, Sinha S. Role of the crosstalk between autophagy and apoptosis in cancer. Journal of Oncology, 2013, 2013: 102735. |

| [14] | Gump JM, Thorburn A. Autophagy and apoptosis:what is the connection?. Trends in Cell Biology, 2011, 21(7): 387-392. DOI:10.1016/j.tcb.2011.03.007 |

| [15] | Nikoletopoulou V, Markaki M, Palikaras K, Tavernarakis N. Crosstalk between apoptosis, necrosis and autophagy. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA)-Molecular Cell Research, 2013, 1833(12): 3448-3459. DOI:10.1016/j.bbamcr.2013.06.001 |

| [16] | Mari?o G, Niso-Santano M, Baehrecke EH, Kroemer G. Self-consumption:the interplay of autophagy and apoptosis. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology, 2014, 15(2): 81-94. DOI:10.1038/nrm3735 |

| [17] | Gordy C, He YW. The crosstalk between autophagy and apoptosis:where does this lead?. Protein & Cell, 2012, 3(1): 17-27. |

| [18] | Harris TE, Lawrence JC Jr. TOR signaling. Science's STKE, 2003, 2003(212): re15. |

| [19] | Geissler EK, Schlitt HJ, Thomas G. mTOR, cancer and transplantation. American Journal of Transplantation, 2008, 8(11): 2212-2218. DOI:10.1111/ajt.2008.8.issue-11 |

| [20] | Kim YC, Guan KL. mTOR:a pharmacologic target for autophagy regulation. The Journal of Clinical Investigation, 2015, 125(1): 25-32. DOI:10.1172/JCI73939 |

| [21] | Wang JR, Whiteman MW, Lian HQ, Wang GX, Singh A, Huang DY, Denmark T. A non-canonical MEK/ERK signaling pathway regulates autophagy via regulating Beclin 1. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 2009, 284(32): 21412-21424. DOI:10.1074/jbc.M109.026013 |

| [22] | Roy B, Pattanaik AK, Das J, Bhutia SK, Behera B, Singh P, Maiti TK. Role of PI3K/Akt/mTOR and MEK/ERK pathway in Concanavalin A induced autophagy in HeLa cells. Chemico-Biological Interactions, 2014, 210: 96-102. DOI:10.1016/j.cbi.2014.01.003 |

| [23] | Xiao Z, Li L, Li Y, Zhou W, Cheng J, Liu F, Zheng P, Zhang Y, Che Y. Rasfonin, a novel 2-pyrone derivative, induces ras-mutated Panc-1 pancreatic tumor cell death in nude mice. Cell Death and Disease, 2014, 5(5): e1241. DOI:10.1038/cddis.2014.213 |

| [24] | Lu Q, Yan S, Sun H, Wang W, Li Y, Yang X, Jiang X, Che Y, Xi Z. Akt inhibition attenuates rasfonin-induced autophagy and apoptosis through the glycolytic pathway in renal cancer cells. Cell Death and Disease, 2015, 6(12): e2005. DOI:10.1038/cddis.2015.344 |

| [25] | Kraft C, Martens S. Mechanisms and regulation of autophagosome formation. Current Opinion in Cell Biology, 2012, 24(4): 496-501. DOI:10.1016/j.ceb.2012.05.001 |

| [26] | Degtyarev M, De Mazière A, Orr C, Lin J, Lee BB, Tien JY, Prior WW, van Dijk S, Wu H, Gray DC, Davis DP, Stern HM, Murray LJ, Hoeflich KP, Klumperman J, Friedman LS, Lin K. Akt inhibition promotes autophagy and sensitizes PTEN-null tumors to lysosomotropic agents. The Journal of Cell Biology, 2008, 183(1): 101-116. DOI:10.1083/jcb.200801099 |

| [27] | Pankiv S, Clausen TH, Lamark T, Brech A, Bruun JA, Outzen H, ?vervatn A, Bj?rk?y G, Johansen T. p62/SQSTM1 binds directly to Atg8/LC3 to facilitate degradation of ubiquitinated protein aggregates by autophagy. The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 2007, 282(33): 24131-24145. DOI:10.1074/jbc.M702824200 |

| [28] | Tanida I, Minematsu-Ikeguchi N, Ueno T, Kominami E. Lysosomal turnover, but not a cellular level, of endogenous LC3 is a marker for autophagy. Autophagy, 2005, 1(2): 84-91. DOI:10.4161/auto.1.2.1697 |

| [29] | Jiang PD, Mizushima N. LC3-and p62-based biochemical methods for the analysis of autophagy progression in mammalian cells. Methods, 2015, 75: 13-18. DOI:10.1016/j.ymeth.2014.11.021 |

| [30] | Mizushima N, Yoshimori T. How to interpret LC3 immunoblotting. Autophagy, 2007, 3(6): 542-545. DOI:10.4161/auto.4600 |

| [31] | Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Tomczak P, Michaelson MD, Bukowski RM, Rixe O, Oudard S, Negrier S, Szczylik C, Kim ST, Chen I, Bycott PW, Baum CM, Figlin RA. Sunitinib versus interferon alfa in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma. The New England Journal of Medicine, 2007, 356(2): 115-124. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa065044 |

| [32] | Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Cella D, Reeves J, Hawkins R, Guo J, Nathan P, Staehler M, de Souza P, Merchan JR, Boleti E, Fife K, Jin J, Jones R, Uemura H, De Giorgi U, Harmenberg U, Wang JW, Sternberg CN, Deen K, McCann L, Hackshaw MD, Crescenzo R, Pandite LN, Choueiri TK. Pazopanib versus sunitinib in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma. The New England Journal of Medicine, 2013, 369(8): 722-731. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa1303989 |

| [33] | Xin H, Zhang CY, Herrmann A, Du Y, Figlin R, Yu H. Sunitinib inhibition of Stat3 induces renal cell carcinoma tumor cell apoptosis and reduces immunosuppressive cells. Cancer Research, 2009, 69(6): 2506-2513. DOI:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-4323 |

| [34] | Giuliano S, Cormerais Y, Dufies M, Grépin R, Colosetti P, Belaid A, Parola J, Martin A, Lacas-Gervais S, Mazure NM, Benhida R, Auberger P, Mograbi B, Pagès G. Resistance to sunitinib in renal clear cell carcinoma results from sequestration in lysosomes and inhibition of the autophagic flux. Autophagy, 2015, 11(10): 1891-1904. DOI:10.1080/15548627.2015.1085742 |

| [35] | Makhov PB, Golovine K, Kutikov A, Teper E, Canter DJ, Simhan J, Uzzo RG, Kolenko VM. Modulation of Akt/mTOR signaling overcomes sunitinib resistance in renal and prostate cancer cells. Molecular Cancer Therapeutics, 2012, 11(7): 1510-1517. DOI:10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-11-0907 |

| [36] | Rini BI, Garcia JA, Cooney MM, Elson P, Tyler A, Beatty K, Bokar J, Ivy P, Chen HX, Dowlati A, Dreicer R. Toxicity of sunitinib plus bevacizumab in renal cell carcinoma. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 2010, 28(17): e284-e285. DOI:10.1200/JCO.2009.27.1759 |

| [37] | Kozloff M, Chuang E, Starr A, Gowland PA, Cataruozolo PE, Collier M, Verkh L, Huang X, Kern KA, Miller K. An exploratory study of sunitinib plus paclitaxel as first-line treatment for patients with advanced breast cancer. Annals of Oncology, 2010, 21(7): 1436-1441. DOI:10.1093/annonc/mdp565 |

| [38] | Blumenschein GR Jr, Ciuleanu T, Robert F, Groen HJM, Usari T, Ruiz-Garcia A, Tye L, Chao RC, Juhasz E. Sunitinib plus erlotinib for the treatment of advanced/metastatic non-small-cell lung cancer:a lead-in study. Journal of Thoracic Oncology, 2012, 7(9): 1406-1416. DOI:10.1097/JTO.0b013e31825cca1c |

| [39] | Luan FL, Ding RC, Sharma VK, Chon WJ, Lagman M, Suthanthiran M. Rapamycin is an effective inhibitor of human renal cancer metastasis. Kidney International, 2003, 63(3): 917-926. DOI:10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00805.x |