任聪1,3, 杜海1,3, 徐岩1,2,3

1.江南大学生物工程学院, 酿酒科学与酶技术研究中心, 江苏 无锡 214122;

2.江南大学食品科学与技术国家重点实验室, 江苏 无锡 214122;

3.江南大学教育部工业生物技术重点实验室, 江苏 无锡 214122

收稿日期:2017-03-07;修回日期:2017-04-18;网络出版日期:2017-04-27

基金项目:国家自然科学基金(31530055);国家重点研发计划(2016YFD0400503)

徐岩, 江南大学生物工程学院教授, 工学博士。主要研究领域为传统酿造食品的微生物(组)学、风味化学和微生物发酵工程, 提出了风味导向的功能微生物研究学术理论, 并建立起相应的应用技术。"基于风味导向的固态发酵白酒生产新技术及应用"项目于2013年获国家技术发明奖二等奖。先后承担传统固态发酵微生物研究的国家自然科学基金3项、国家"973项目"2项、国家"863计划"2项、国家支撑计划1项, 目前主持国家自然科学基金重点项目"基于组学技术的我国优势酿造食品特征风味组分及其微生物代谢机制"和承担国家重点研发计划"传统酿造食品制造关键技术研究与装备开发"等国家级项目。相关成果发表在Applied & Environmental Microbiology, Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, Trends in Food Science & Technology等学术期刊

*通信作者:徐岩, Tel:+86-510-85918201;E-mail:yxu@jiangnan.edu.cn

摘要:传统发酵食品风味独特、营养丰富,多采用自然接种方式进行生产,部分类型的生产技艺已具有数千年的历史。近年来应用新技术手段对传统发酵食品发酵过程进行的研究表明,传统发酵食品微生物组具有丰富的科学内涵和重要的应用价值。本文就我国传统发酵食品微生物组的基本特征、研究进展和发展方向进行了简要的评述。

关键词:中国传统发酵食品 微生物组 微生物菌群 定向控制

Advances in microbiome study of traditional Chinese fermented foods

Cong Ren1,3, Hai Du1,3, Yan Xu1,2,3

1.Brewing and Enzyme Technology Center, School of Biotechnology, Jiangnan University, Wuxi 214122, Jiangsu Province, China;

2.State Key Laboratory of Food Science and Technology, Jiangnan University, Wuxi 214122, Jiangsu Province, China;

3.Key Laboratory of Industrial Biotechnology, Jiangnan University, Wuxi 214122, Jiangsu Province, China

Received 07 March 2017; Revised 18 April 2017; Published online 27 April 2017

*Corresponding author: Yan Xu, Tel:+86-510-85918201;E-mail: yxu@jiangnan.edu.cn

Supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31530055) and by the National Key Research and Development Program (2016YFD0400503)

Abstract: Traditional Chinese fermented foods, usually produced through fermentation by spontaneously inoculation, are characterized by their special flavors and rich nutrients. The techniques of some traditional fermented foods have thousands of years of history. In recent years, new technologies have been used to explore the mysteries of fermenting processes for traditional fermented foods worldwide, revealing that traditional fermentation systems are valuable to both basic and application research. In this review, we summarize the general features and recent progresses in the microbiome study of traditional Chinese fermented foods, and try to predict the future research directions.

Key words: traditional Chinese fermented food microbiome microbiota targeting control

食品发酵技艺是一种古老的用于食品长期保存和风味食品加工的生物技术,已经具有数千年的历史[1-3]。发酵食品的制造利用了有益微生物的发酵作用,将原料中的淀粉、蛋白质和脂肪三大营养物质进行分解、转化,产生相应的代谢产物,赋予食品拥有发酵之前所不具备的独特风味和营养价值。国外传统发酵食品主要包括奶酪、酸奶、清酒、韩国泡菜、德国泡菜等[3]。中国传统发酵食品包括了食醋、黄酒、白酒、酱油、豆腐乳、豆瓣酱、泡菜等,这些发酵食品是中国饮食文化的重要组成部分,历经数千年的发展形成了独特的生产方式和风味特征[4]。

近年来的研究表明发酵食品对健康具有积极的促进作用,如发酵乳制品可以改善肠道微生物菌群结构,苹果醋具有抗氧化防护功能,葡萄酒具有降低冠心病发生的作用,发酵豆制品产生的纤溶酶具有高抗凝血的活性[1, 5-8]。由于国内外典型传统发酵食品多采用自然接种方式进行发酵,原料、工艺和环境三类因素共同决定了发酵过程中的微生物菌群种类及其丰度,进而影响相应发酵食品的安全性、风味品质和营养功能。传统发酵食品的生产需多种微生物菌群协调作用,对这些微生物菌群的结构组成、代谢功能和相互作用关系的解析将有利于定向控制发酵过程中微生物种类,提高生产效率,改善传统发酵食品风味和保障发酵食品安全。

传统发酵食品生产中涉及种类众多的微生物,这些微生物形成复杂的菌群结构,所代谢产生的风味组分复杂多样,生长代谢过程同时可以改良食品结构和质地[9-10]。传统的可培养方法和分子微生物生态学方法难以对如此复杂的微生物菌群结构和功能进行系统的分析。面对此类挑战,近年来蓬勃发展起来的微生物组学技术因其建立于微生物学、功能基因组学、代谢组学、生物信息学和系统生物学等多学科基础之上,可以从本质上揭示自然接种的微生物菌群如何影响食品发酵过程,并最终决定传统发酵食品的安全性、风味特征和营养功能。中国传统发酵食品微生物组研究将有助于解析传统发酵食品微生物的代谢机制及其复杂的相互作用关系,为食品微生物研究提供新的研究思路和更为先进的研究手段,推动传统发酵食品产业的升级改造。

我国传统发酵食品的微生物组学研究起步虽晚于欧美和日韩对本国传统发酵食品微生物组的研究[3, 11-12],但近年来也逐步取得了一系列重要进展,本文将着重介绍近年来国内外在我国传统发酵食品微生物组研究方面所取得的进展,并对未来发展方向和应用前景进行了展望。

1 我国传统发酵食品微生物体系的基本特征 传统发酵食品风味独特、营养丰富,其独特的风味往往由微量风味物质所呈现,这些风味物质和营养成分多由复合菌群代谢产生(图 1)。微生物组学研究方法和相关技术的应用逐步解析出我国传统发酵食品微生物组的物种组成,逐渐认识到环境因子如何选择不同类型的微生物菌群,同时我国种类多样的传统发酵食品体系为研究微生物组学的基本科学问题提供了多种类型的可跟踪微生物生态系统(表 1)。

|

| 图 1. 中国传统发酵食品(食醋、白酒、黄酒)的生产流程 Figure 1. Schematic diagram of the general production processes of traditional Chinese fermented foods (Vinegar, baijiu and Huangjiu). |

| 图选项 |

表 1. 中国传统发酵食品体系的微生物多样性和风味物质多样性 Table 1. The Diversities of microbes and flavors in traditional chinese fermented foods

| Type of food | Main ingredients | Major microbial genera or species | Major identified flavors | Fermentation type | Opportunities to study |

| Huangjiu(Rice wine) | rice, wheat, millet | ~200 species[13-14] Filamentous fungi: Aspergillus, Rhizopus Yeast: Saccharomyces, Candida, Cryptococcus Bacteria: Bacillus, Lactobacillus | ~900 volatile components [1]; key aroma volatiles[16]: 3-methylbutanoic acid, ethyl butyrate, vanilline, ethyl caproate, 3-methyl butanal, butyrate, dimethyl trisulfide, phenethyl alcohol, etc. Non-volatiles[17]: oligosaccharide, amino acids (e.g. y-aminobutyric acid), catechinic acid compounds, rutin, etc. | aerobic—micro-aerobic, semi-solid state fermentation | Community interaction and dynamics |

| Baijiu(Chinese liquor) | sorghum, wheat, barley, rice, maize, pea | ~299 prokaryotic genera[18], ~81 filamentous fungi and yeast species[19] Filamentous fungi: Rhizopus, Paecilomyces, Aspergillus, Mucor Yeast: Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Zygosaccharomyces bailii, Schizosaccharomyces pombe Bacteria: Lactobacillus, Weissella, Pediococcus, Bacillus, Clostridium | 1600~1800 flavor components[20]; key aroma volatiles[21]: acetate, butyrate, caproiate, caproate, ethyl acetate, ethyl butyrate, ethyl caproate, ethyl caprylate, ethyl lactate, butanol, octanol, dimethyl sulfide, dimethyl trisulfide, 3-methylbutanoic acid, tetramethylpyrazine, 3-(methylthio) propionaldehyde, β-damascenone, etc. | aerobic→microaerobic→anaerobic, solid state fermentation (strong-, light-and soy sauce-aroma types) or semi-solid state fermentation (rice-aroma type) | Community interaction and dynamics, abiotic selection due to variable operating conditions, metabolic cooperation in anaerobic systems, evolution due to wide geographical distributions, microbes-environment interactions |

| Vinegar | sorghum, rice, wheat | ~202 filamentous fungi and yeast genera, ~151 bacterial genera[22] Filamentous fungi: Aspergillus, Rhizopus, Paecilomyces, Mucor Yeast: Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Pichia anomala Bacteria: Lactobacillus, Acetobacter | ~88 identified flavor components, 59 key aroma volatiles [22]: acetate, ethyl acetate, acetoin, 2, 3-butanedione, 3-methyl-1-butanol, oxole, tetramethylpyrazine, etc. ~29 identified non-volatiles[22]including 18 amino acids, etc. | aerobic—micro-aerobic—aerobic, solid or semi-solid state fermentation | Community interaction and dynamics, biotic selection due to variable operating conditions, evolution due to wide geographical distributions |

| Soy sauce | soybean | ~22 genera [23-24] Filamentous fungi: Aspergillus Yeast: Zygosaccharomyces rouxii, Toruiopsis, Candida Bacteria: Weissella, Lactobacillus, Lactobacillus | Identified flavor components[25]:ethyl acetate, long-chain fatty acid ethyl esters, 4-ethyl guaiacol, phenethyl alcohol, 5-methyl-2-phenyl-2-hexenal, polypeptides, amino acids, etc. | aerobic—micro-aerobic, solid or semi-solid state fermentation | Community interaction and dynamics, biotic selection due to variable operating conditions |

| Fermented bean curd | soybean | ~16 genera[26-27] Filamentous fungi: Mucor, Rhizopus Yeast: Zygosaccharomyces rouxii Bacteria: Lactobacillus, Bacill-us | polypeptides, amino acids, fatty acids, etc. | aerobic—anaerobic | Community interaction and dynamics |

| Chinese pickles | vegetables | ~25 genera[28-29] Yeast: Saccharomyces, Pichia Bacteria: Lactobacillus, Pediococcus, Weissella, Lactococcus | ~30 identified flavor components[30]: lactate, acetate, dimethyl disulfide, dimethyl trisulfide, acetaldehyde, etc. | micro-aerobic or anaerobic | Community interaction and dynamics |

表选项

我国传统发酵食品微生物体系具有以下基本特征。

1.1 微生物物种多样性高、代谢产物复杂多样 我国传统发酵食品多采用开放式发酵体系进行生产,其发酵过程需多种微生物协调作用完成,其中的微生物种类众多、结构复杂。如表 1,酿造食品(包括醋、酱油、白酒、黄酒)是传统发酵食品的重要组成部分,这些酿造体系的微生物菌群具有较高的物种多样性(>200属),可以产生上千种的风味化合物,但目前仅少量的微生物实现了纯培养鉴定。

1.2 发酵过程中的微生物种类和功能可以通过原料和工艺进行选择与控制 因传统发酵食品生产多采用自然接种,三类因素决定着酿造体系中的初始微生物构成(图 1):(1) 酿造原料及其预处理方式:原料自身会携带部分微生物,其预处理方式可改变物料微结构,从而影响固态基质对微生物的选择作用;(2) 酿造工艺参数:包括发酵温度、氧含量、酸碱度、水活度和发酵时间等;(3) 环境来源:包括生产环境空气和生产器具。

微好氧发酵和厌氧发酵在我国传统发酵食品生产中起着重要的作用,如食醋、黄酒、白酒、泡菜生产过程中先进行短暂的好氧发酵,随着氧气的耗尽进入微好氧或厌氧发酵阶段(生产食醋时在微好氧/厌氧产醇发酵后进行的醋酸发酵为好氧发酵) (表 1)。传统发酵食品生产过程中需要对工艺参数和原料进行很好的控制,以保证正常生产所需菌群的生长,同时预防有害微生物的生长繁殖。虽然传统发酵食品生产通过自然接种完成,但通过工艺控制仍然可以生产出质量相对稳定的产品,这提示我们传统发酵食品体系中的微生物可以具有相对稳定的菌群结构。

1.3 微生物群系(microbiota)之间及其内部成员物种之间存在着复杂的相互作用关系 传统观点认为霉菌进行大分子分解,酵母产醇(也产较低浓度的风味化合物),细菌的主要贡献为产风味化合物。该认识具有一定的合理性,但同时也应注意到这种认识是基于部分纯培养微生物的生理代谢特征进行的判断,而对于未分离培养微生物的功能认识严重不足,更重要的是对多菌群发酵体系中微生物相互作用机制以及这种机制对发酵过程的影响尚缺乏系统的研究。

2 中国传统发酵食品微生物组研究进展 2.1 种曲微生物组研究 酿造食品(醋、黄酒、白酒和酱油)是我国传统发酵食品的重要类型,生产这些食品通常以曲作为发酵剂(starter),以实现糖化和发酵的同步进行,这区别于西方酿造的先糖化后发酵方式,该特点是东方酿造区别于西方酿造的典型特征之一[31]。(种)曲的制作以谷物(如大麦、小麦、豌豆)作为培养基质,在合适的条件下富集酿造环境中的微生物。曲在东方酿造中之所以具有重要的地位,从酿造功能角度分析,原因在于:(1) 霉菌分泌的淀粉酶、蛋白酶和脂肪酶可分别实现对淀粉、蛋白质和糖类的降解;(2) 制曲中多种类型酵母(产醇、产香)可以得到富集,从而赋予后续发酵持续的发酵力和产香能力;(3) 曲中富集的细菌可以合成多种类型的风味化合物。

近年来的多项研究对种曲中微生物的菌群结构和基本酿造功能进行了解析[19, 32-35],扩增子测序(16S rRNA测序和ITS测序)表明曲中的霉菌主要包括曲霉属、毛霉属、根霉属和根毛霉属,酵母主要包括酵母属、假丝酵母属、伊萨酵母属、毕赤酵母属、接合酵母属和裂殖酵母属,细菌主要包括乳杆菌属、片球菌属、魏斯氏菌属和芽孢杆菌属。环境因子(温度、湿度)是决定这些微生物在种曲中结构组成和丰度的关键因素[32, 36],同时微生物的生物地理分布也对大曲微生物的组成结构具有重要影响[37]。目前对霉菌的功能解析较多集中于淀粉利用能力的分析,如鉴定出了拟青霉属(Paecilomyces)、曲霉属(Aspergillus)、根霉属(Rhizopus)和毛霉属(Mucor)微生物是重要的α-淀粉酶和葡糖淀粉酶分泌菌[32, 38]。就酵母而言,除广泛存在的酿酒酵母外,其他类型酵母也存在于曲中,如扣囊复膜酵母(Saccharomycopsis fibuligera)和异常毕赤酵母(Pichia anomala)在某些类型曲中的丰度甚至远高于酿酒酵母(Saccharomyces cerevisiae)[34]。曲中存在多种类型的细菌,其中芽孢杆菌属、乳杆菌属和醋酸杆菌属具有明确的酿造功能[37, 39]。Wang等人对浓香型白酒酿造体系中原核微生物的来源进行了解析,发现大曲是后续主发酵过程中好养和兼性厌氧菌的主要来源,主发酵过程中74%的原核微生物来源于大曲[18]。因此众多研究者尝试通过生物强化改良大曲的酿造功能,但最近的一项研究表明种曲微生物菌群结构具有较强的鲁棒性,添加部分菌种进行强化虽能提高部分微生物的丰度,但对菌群结构组成影响较小[40]。

曲中富含种类众多的霉菌、酵母和细菌三大类群微生物[31-32],这些微生物在制曲原料中的定殖、组装和相互作用对后续酿造过程具有重要的影响,其代谢特征对产品的安全性、营养和风味起着关键作用。以下几方面的问题尚需进行深入研究:(1) 综合利用宏基因组学、宏转录组学和代谢组学技术,解析霉菌、酵母和细菌三大类群微生物在大曲中的微生物群落组装机制,揭示群落组装的影响因素及其对后续主发酵的影响;(2) 系统解析种曲微生物组的全基因组信息,挖掘新基因资源;(3) 对曲中微生物(尤其是难培养微生物)进行种水平的鉴定,建立难培养微生物的可培养技术,挖掘微生物种质资源。

2.2 主发酵过程的微生物组学研究 以黄酒、白酒和醋的生产为例,酿造主发酵过程首先将原料(淀粉质为主,含一定比例的蛋白质、脂肪)与曲进行适当比例的混合,通过微生物自然生长完成发酵过程。虽然种曲微生物是主发酵过程微生物的主要来源,但由于中国传统发酵食品的生产多采用密闭隔绝空气的方式,种曲中带入的霉菌为好氧微生物,其在发酵初期迅速衰亡,因此发酵过程中的主体微生物为酵母和细菌[41]。研究者对黄酒、白酒和醋发酵过程中微生物菌群结构的组成及其动力学变化过程进行了初步的解析,研究结果表明原料种类、原料物理状态和工艺(氧气、温度、水活度、酸碱度)对微生物组成具有重要的影响[13, 18, 22, 42]。

2.2.1 主发酵过程中微生物之间的相互作用关系:: 酵母是传统发酵食品生产过程主要的乙醇产生微生物,其产生的乙醇可以抑制多种有害微生物的生长[43]。酵母同时还可以代谢产生多种风味化合物,如酿酒酵母在谷物培养基质中可以产生13种以上的萜烯类化合物[44]。除酿酒酵母外,其他酵母在发酵过程中也起着重要的作用,如Kong等人利用共现性关联分析了清香型白酒酿造过程中的酵母群落多样性和风味化合物代谢谱,对比酵母种属结构组成与风味化合物组成,鉴定出酿造环境中存在的8种酵母可能对58种挥发性风味化合物的合成具有贡献[45]。发酵过程中的环境变化(含氧量、水活度、温度、酸度等)对发酵体系中的酵母组成结构具有重要的影响,如酱香型白酒发酵过程的不同阶段(即轮次)具有不同的酵母种属结构组成[46]。后续研究表明发酵体系中不同酵母种属间具有较为复杂的相互作用关系,如在一项利用5种酵母进行的组合发酵研究中发现,葡萄汁酵母(Saccharomyces uvarum)和斯瓦酵母(Saccharomyces servazzii)可以促进酿酒酵母和东方伊萨酵母(Issatchenkia orientalis)的生长,而对异常威克汉姆酵母(Wickerhamomyces anomalus)的生长无显著影响;代谢产物分析表明葡萄汁酵母和斯瓦酵母加入后同时改变了酿酒酵母和东方伊萨酵母的风味化合物合成谱(增加酯类、醇和酸的合成,而降低芳香族化合物、醛和酮的合成),但这种偏利互生的分子机制尚不清晰[47]。 Lu等人[48]利用宏基因组学就镇江香醋关键香气成分(乙偶姻)合成的微生物菌群展开研究,利用宏基因组学和代谢组学联合分析发现巴斯德醋酸杆菌(Acetobacter pasteurianus)和4种乳杆菌(布氏乳杆菌L. buchneri、罗伊氏乳杆菌L. reuteri、发酵乳杆菌L. fermentum和短乳杆菌L. brevis)可能参与了乙偶姻的生物合成;进一步的可培养验证表明巴斯德醋酸杆菌与乳杆菌单独培养时均仅能产生少量的乙偶姻,但当与短乳杆菌和发酵乳杆菌进行共培养时乙偶姻的合成大幅度提高。 以上白酒和食醋酿造中的微生物相互作用研究表明酿造体系中的群体微生物代谢特征不同于纯培养时的代谢特征,这种代谢互作机制可以用于增加风味组分或营养成分的合成,但目前尚不清楚这些代谢互作的分子机理。

2.2.2 细菌在中国传统发酵食品生产中的重要作用:: 东方酿造区别于西方酿造的另一典型特征在于东方酿造尤其重视细菌在产风味化合物方面的应用。细菌在西方部分传统发酵食品中占据重要地位,如奶酪、发酵肉制品等[3];但对于啤酒和葡萄酒的酿造而言,细菌通常被认为是导致发酵异常的杂菌[49-50]。与此对应的是,细菌在东方酿造中具有极其重要的作用,如芽孢杆菌属(Bacillus)和梭菌属(Clostridium)微生物。芽孢杆菌,包括地衣芽孢杆菌(Bacillus licheniformis),生长于好氧环境中(如酱香型白酒发酵的堆积过程和豆制品发酵过程),是重要的吡嗪类化合物合成菌(如四甲基吡嗪是酱香型白酒的关键风味化合物)[51-52];梭菌,包括Clostridium sp. BPY5和克氏梭菌(Clostridium kluyveri),生长于厌氧环境中(如浓香型白酒酿造窖泥中),是重要的短中链脂肪酸合成菌,分别参与了丁酸和己酸的合成,造就了浓香型白酒的典型特征[53-54]。可见中国传统发酵食品生产所采取的不同工艺(如氧含量)可以筛选和富集出不同类型和代谢特征的微生物菌群。 乳酸菌是传统发酵食品生产过程中重要的结构功能菌,广泛存在于黄酒、白酒、醋、酱油和泡菜发酵体系中(表 1)。乳酸菌具有高效的乳酸产生能力和细菌素(如乳酸链球菌肽)分泌能力,其本身具有较高的酸耐受能力,可以抑制多种类型有害微生物的生长,对于保证发酵食品的安全性具有十分重要的作用[55]。乳杆菌属(Lactobacillus)、魏斯氏菌属(Weissella)和片球菌属(Pediococcus)是酿造体系中广泛存在的乳酸菌[56-57]。在酿酒过程和制醋的产醇阶段,乳酸菌是绝对优势菌,其丰度可占原核微生物的70%-90%[13, 18, 22, 58],因此我们推测酿造体系中高丰度的乳酸菌对于维持酿造过程的食品安全性具有重要意义。尽管已经证实发酵食品中的乳酸菌对部分有害菌具有一定的抑制作用[59],但同时也应注意到乳酸菌的抗菌谱较窄[60],且不同类型乳酸菌甚至同种乳酸菌的不同菌株间的抗菌性能均可能具有较大差异[61],因此如何有效利用乳酸菌的抗菌性能对有害微生物进行有效控制,同时又不影响正常酿造菌群的结构和功能,是未来乳酸菌相关研究的重要任务。 2.3 微生物与生产环境之间的相互作用机制 酿造环境的微生物来源至少包括酿造环境空气(如曲房空气)和发酵容器(如窖池,其中的窖泥为浓香型白酒酿造供给厌氧菌种源)这二大来源。由于中国传统发酵食品生产多采用开放式自然接种,环境微生物种类和丰度对传统发酵食品的品质和安全具有重要的影响。多项研究表明种曲的微生物组成对后续主发酵过程的微生物菌群结构和丰度具有重要影响[4, 34, 38, 62],但对于制曲环境中的微生物组成结构及其对种曲微生物结构的影响尚不清晰,也鲜有研究[63]。

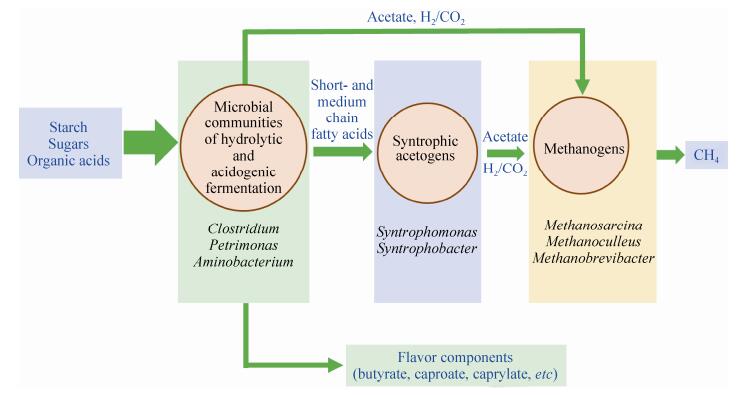

窖泥厌氧生境是由细菌和产甲烷古菌组成的共生系统,目前的研究表明窖泥为浓香型白酒发酵过程贡献了14%的原核微生物(主要为厌氧菌),但尚不清楚窖泥中所栖息厌氧微生物的最初来源[18]。在生产实践中人们发现合理的窖泥制作方法和管理方式可以维持窖泥连续使用数百年以上。近年来通过对不同窖龄(建窖时间长短)的窖泥微生物结构进行分析,发现随着连续使用时间的增加,窖泥中的梭菌(丁酸、己酸合成菌)和产甲烷古菌丰度不断增加,窖泥质量逐渐趋于稳定(优质窖泥更有利于酿造出优质的产品),因此研究人员推测窖泥可以在数百年的连续使用过程中保持微生物群落结构的基本稳定[64-65]。最近的一项研究比较了不同质量等级(退化和优质)窖泥的微生物组成结构,发现优质窖泥具有更高的物种多样性[66]。如图 2所示,基于这些微生物的底物利用和代谢产物特征,我们推测优质窖泥微生物菌群具有从复杂碳源降解到甲烷生成的代谢互作网络,即当窖泥中同时存在水解/发酵菌群(microbial communities of hydrolytic and acidogenic fermentation)、互营养产乙酸菌群(Syntrophic acetogens)和产甲烷菌群(Methanogens),且该三类菌群代谢互作趋于稳定时,窖泥微环境酸碱度将维持偏中性,窖泥中的微生物群落结构将趋于稳定[66]。反之,如产酸菌群过量繁殖(如乳杆菌属微生物),过量的乳酸无法通过窖泥微生物菌群代谢互作转化为甲烷,窖泥将迅速退化[66]。

|

| 图 2. 窖泥微生物各功能菌群间的代谢互作 Figure 2. The metabolic cooperation among microbiotas in pit mud. |

| 图选项 |

我国特有的窖泥生态系统具有丰富的厌氧微生物多样性[64-69],生产实践已经证明该系统物种多样性高时具有良好的鲁棒性,对该系统中厌氧微生物群落组装、物质传递和能量传递机制的解析将丰富我们对厌氧降解系统的认识。此外,如同瘤胃厌氧消化系统的机制解析促进了厌氧生物技术的发展[70-71],窖泥厌氧生态系统的深入研究将有助于新型厌氧微生物资源的开发。

2.4 传统发酵食品微生物组研究促进新型发酵技术的形成 国外现代酿造区别于传统酿造的特点是前者利用了纯菌种发酵,如日本在中国制曲技术基础上发展出清酒和日本酱油酿造技术。然而由于纯种发酵微生物能够产生的风味代谢产物有限,纯种发酵食品在其风味典型性方面与传统的多菌种自然接种发酵产品仍然具有一定的差距。微生物组学研究的重点是从系统生物学水平解析复杂菌群体系发挥功能的机制,而建立在此基础上的微生物组工程(microbiome engineering)让研究者可以采用工程化的理念设计出高效的多菌种体系[72],为构建多菌种可控发酵体系,实现产品的高效、定向生产提供了很好的研究思路。

目前研究人员在微生物菌群组合发酵方面进行了初步的尝试,如Wu等人[73]发现起始发酵菌群的结构组成对发酵产品的品质具有重要的影响,该项研究比较了3种酵母(酿酒酵母、膜醭毕赤酵母Pichia membranaefaciens、东方伊萨酵母)和2种芽孢杆菌(地衣芽孢杆菌Bacillus licheniformis、解淀粉芽孢杆菌Bacillus amyloliquefaciens)的多种组合发酵方式并应用于芝麻香白酒的生产工艺研究,发现酿酒酵母、东方伊萨酵母、地衣芽孢杆菌分别产生了不同类型的风味化合物,而膜醭毕赤酵母和解淀粉芽孢杆菌虽对风味贡献有限,却可以促进前三种主要风味产生微生物的生长[73]。这项研究同时表明以风味导向(即微生物产风味化合物导向)作为菌群组合的依据,合理利用微生物间的相互作用对定向、高效控制微生物菌群代谢具有重要的指导价值。

徐岩等人在人工构建特定功能菌群用于传统发酵食品生产方面进行了初步的尝试,如从我国南方传统小曲清香型白酒发酵体系的观音土曲中,通过DGGE方法与可培养分离相结合鉴定出了关键的功能微生物:米根霉(Rhizopus oryzae)、酿酒酵母、异常毕赤酵母和东方伊萨酵母[74-75];基于这4种微生物构建出了小曲清香型白酒发酵的最小功能微生物菌群,完成了大规模的机械化改造,成功实现了小曲清香型白酒生产的产业升级[75]。

3 展望 我国发酵食品种类众多、微生物资源丰富,生产实践经验中所蕴含的科学内涵有待深入解析,复杂多样的微生物菌群所蕴含的应用价值尚需深入挖掘。我国传统发酵食品微生物组研究将有助于:(1) 丰富微生物组学的基本理论;(2) 推动我国传统发酵食品生产过程中的微生物定向调控技术的建立,促进传统发酵食品工业的可持续发展;(3) 发掘微生物种质资源和基因(酶)资源。

3.1 丰富微生物组学的基本理论 微生物菌群组装的模式、过程和机制解析是微生物组学研究的基本问题[3]。食品发酵系统是人工建立的、可高度重复和可跟踪的微生物生态系统,其微生物组成结构和功能可以通过生产环境、原料组成和工艺参数等进行较好的控制,可以满足微生物菌群组装机制解析需要的可重复、具有相对稳定性、易操作的要求。种曲可以用于解析霉菌、酵母和细菌三大类群微生物的组装机制,主发酵过程可以用于研究酵母、细菌的组装和相互作用机制,窖泥可以用于细菌与产甲烷古菌之间的群落组装和相互作用机制。

发酵食品体系所具有的可重复、可跟踪、可扰动的特点为探究微生物组学的基本科学问题提供了潜在的模式生态系统,如国外****尝试以可跟踪的食品发酵系统(发酵奶酪皮)作为模式微生物生态系统[12]。我国特有的发酵食品(尤其是酿造食品)体系可以集成霉菌、酵母、细菌和产甲烷古菌四大类群微生物,为探讨多种生物因素和非生物因素干扰下的微生物菌群演替规律和相互作用机制提供诸多便利。

3.2 提升与改造传统产业 目前我国传统发酵食品生产过程的机械化、智能化水平较低,虽然自然接种可以网罗多种多样的微生物,但这种接种方式受气候、人为操作等因素影响较大,难以保证产品质量的稳定,生产效率较低,且具有一定的食品安全风险。传统发酵食品微生物组的基础和应用研究将促进传统产业的升级、改造,包括提高传统产业的原料利用率、降低能耗,生产出更美味、更营养的发酵食品。

3.3 微生物资源开发 传统发酵食品生产技艺数千年的传承过程也是人类数千年的微生物驯化过程,酿造体系中的微生物可能与人类协同进化,其中某些微生物的生理代谢特征可能不同于自然界存在的未驯化微生物[76-77]。我国具有生境独特、种类多样的发酵食品微生物资源。研究者从中华根霉(种曲中常见的一种霉菌)中鉴定出了具有高催化活性和底物适用性的“甘油酯酶-磷脂酶”双功能脂肪酶编码基因,对该基因蛋白质工程改造大幅度提高了该酶的热稳定性和降低了生产成本,填补了该类脂肪酶在国内的工业化生产空白[78];从酱香型白酒体系中筛选出了抗葡萄糖阻遏效应的酿酒酵母菌株,以及耐高温和耐酸的酵母菌株[79-80];从酱香型白酒酿造体系中筛选得到高产表面素的解淀粉芽孢杆菌[81];从浓香型白酒酿造体系中筛选得到新型的丁酸产生菌[54]和己酸产生菌[53];从泡菜发酵体系中分离到新型细菌素合成菌株[82]。

目前对发酵食品微生物资源的挖掘多采用可培养方法进行,未来研究需要在明确难培养微生物的功能基础上,建立难培养微生物的可培养方法,深入挖掘我国传统发酵食品微生物种质资源和基因资源,为现代生物技术产业提供新型微生物、酶和基因元件。

参考文献

| [1] | Marco ML, Heeney D, Binda S, Cifelli CJ, Cotter PD, Foligne B, Ganzle M, Kort R, Pasin G, Pihlanto A, Smid EJ, Hutkins R. Health benefits of fermented foods:microbiota and beyond.Current Opinion in Biotechnology, 2016, 44: 94–102 |

| [2] | McGovern PE, Zhang J, Tang J, Zhang Z, Hall GR, Moreau RA, Nunez A, Butrym ED, Richards MP, Wang CS, Cheng G, Zhao Z, Wang C. Fermented beverages of pre-and proto-historic China.Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences U.S.A, 2004, 101(51): 17593–17598DOI:10.1073/pnas.0407921102. |

| [3] | Wolfe BE, Dutton RJ. Fermented foods as experimentally tractable microbial ecosystems.Cell, 2015, 161(1): 49–55DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2015.02.034. |

| [4] | Jin G, Zhu Y, Xu Y. Mystery behind Chinese liquor fermentation.Trends in Food Science & Technology, 2017, 63: 18–28 |

| [5] | Corder R, Douthwaite JA, Lees DM, Khan NQ, Viseu Dos Santos AC, Wood EG, Carrier MJ. Endothelin-1 synthesis reduced by red wine.Nature, 2001, 414(6866): 863–864DOI:10.1038/414863a. |

| [6] | David LA, Maurice CF, Carmody RN, Gootenberg DB, Button JE, Wolfe BE, Ling AV, Devlin AS, Varma Y, Fischbach MA, Biddinger SB, Dutton RJ, Turnbaugh PJ. Diet rapidly and reproducibly alters the human gut microbiome.Nature, 2014, 505(7484): 559–563 |

| [7] | Nakamura K, Ogasawara Y, Endou K, Fujimori S, Koyama M, Akano H. Phenolic compounds responsible for the superoxide dismutase-like activity in high-Brix apple vinegar.Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2010, 58(18): 10124–10132DOI:10.1021/jf100054n. |

| [8] | Wei X, Luo M, Xu L, Zhang Y, Lin X, Kong P, Liu H. Production of fibrinolytic enzyme from Bacillus amyloliquefaciens by fermentation of chickpeas, with the evaluation of the anticoagulant and antioxidant properties of chickpeas.Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2011, 59(8): 3957–3963DOI:10.1021/jf1049535. |

| [9] | Dunkel A, Steinhaus M, Kotthoff M, Nowak B, Krautwurst D, Schieberle P, Hofmann T. Nature's chemical signatures in human olfaction:a foodborne perspective for future biotechnology.Angewandte Chemie International Edition, 2014, 53(28): 7124–7143DOI:10.1002/anie.201309508. |

| [10] | Tamang JP, Watanabe K, Holzapfel WH. Review:diversity of microorganisms in global fermented foods and beverages.Frontiers in Microbiology, 2016, 7: 377 |

| [11] | Bokulich NA, Lewis ZT, Boundy-Mills K, Mills DA. A new perspective on microbial landscapes within food production.Current Opinion in Biotechnology, 2016, 37: 182–189DOI:10.1016/j.copbio.2015.12.008. |

| [12] | Wolfe BE, Button JE, Santarelli M, Dutton RJ. Cheese rind communities provide tractable systems for in situ and in vitro studies of microbial diversity.Cell, 2014, 158(2): 422–433DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2014.05.041. |

| [13] | Hong X, Chen J, Liu L, Wu H, Tan H, Xie G, Xu Q, Zou H, Yu W, Wang L, Qin N. Metagenomic sequencing reveals the relationship between microbiota composition and quality of Chinese Rice Wine.Scientific Reports, 2016, 6: 26621DOI:10.1038/srep26621. |

| [14] | 刘芸雅. 绍兴黄酒发酵中微生物群落结构及其对风味物质影响研究. 江南大学硕士学位论文, 2015. |

| [15] | 陈双. 中国黄酒挥发性组分及香气特征研究. 江南大学博士学位论文, 2013. |

| [16] | Chen S, Xu Y, Qian MC. Aroma Characterization of Chinese Rice Wine by Gas Chromatography-Olfactometry, Chemical Quantitative Analysis, and Aroma Reconstitution.Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, 2013, 61(47): 11295–11302DOI:10.1021/jf4030536. |

| [17] | 谢广发. 绍兴黄酒功能性组分的检测与研究. 江南大学硕士学位论文, 2005. |

| [18] | Wang X, Du H, Xu Y. Source tracking of prokaryotic communities in fermented grain of Chinese strong-flavor liquor.International Journal of Food Microbiology, 2017, 244: 27–35DOI:10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2016.12.018. |

| [19] | Zheng XW, Yan Z, Han BZ, Zwietering MH, Samson RA, Boekhout T, Robert Nout MJ. Complex microbiota of a Chinese "Fen" liquor fermentation starter (Fen-Daqu), revealed by culture-dependent and culture-independent methods.Food Microbiology, 2012, 31(2): 293–300DOI:10.1016/j.fm.2012.03.008. |

| [20] | Zhu SM, Xu ML, Ramaswamy HS, Yang MY, Yu Y. Effect of high pressure treatment on the aging characteristics of Chinese liquor as evaluated by electronic nose and chemical analysis.Scientific Reports, 2016, 6: 30273DOI:10.1038/srep30273. |

| [21] | Fan WL, Shen HY, Xu Y. Quantification of volatile compounds in Chinese soy sauce aroma type liquor by stir bar sorptive extraction and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry.Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture, 2011, 91(7): 1187–1198DOI:10.1002/jsfa.v91.7. |

| [22] | Wang ZM, Lu ZM, Shi JS, Xu ZH. Exploring flavour-producing core microbiota in multispecies solid-state fermentation of traditional Chinese vinegar.Scientific Reports, 2016, 6: 26818DOI:10.1038/srep26818. |

| [23] | Sulaiman J, Gan HM, Yin WF, Chan KG. Microbial succession and the functional potential during the fermentation of Chinese soy sauce brine.Frontiers in Microbiology, 2014, 5: 556 |

| [24] | Yan YZ, Qian YL, Ji FD, Chen JY, Han BZ. Microbial composition during Chinese soy sauce koji-making based on culture dependent and independent methods.Food Microbiology, 2013, 34(1): 189–195DOI:10.1016/j.fm.2012.12.009. |

| [25] | Zhang LQ, Zheng J, Huang J, Wu ZD, Zhou RQ. Analysis of volatile aroma components in fermented soy sauce.China Condiment, 2013, 38(2): 62–66(in Chinese) 张立强, 郑佳, 黄钧, 吴重德, 周荣清. 酿造酱油挥发性香气成分及多重辨析.中国调味品, 2013, 38(2): 62–66. |

| [26] | 曹翠峰. 大豆发酵食品-腐乳的微生物学研究. 中国农业大学硕士学位论文, 2001. |

| [27] | Wang FJ, Lu F, Qu Y, Zhang J, Huang CD. Separation and identification of lactic acid bacteria isolated from Sufu.China Condiment, 2010, 35(7): 98–101(in Chinese) 王夫杰, 鲁绯, 渠岩, 张建, 黄持都. 腐乳中乳酸菌的分离与鉴定.中国调味品, 2010, 35(7): 98–101. |

| [28] | Liang H, Zhang A, Wu Z, Liu C, Zhang W. Characterization of microbial community during the fermentation of Chinese Homemade paocai, a traditional fermented vegetable food.Food Science and Technology Research, 2016, 22(4): 467–475DOI:10.3136/fstr.22.467. |

| [29] | Zhang XJ, Xia S, Chen J, Feng X, Liu SQ. Research of culturable microbial community in Sichuan pickles.China Condiment, 2015, 40(12): 64–68(in Chinese) 张晓娟, 夏珊, 陈洁, 冯霞, 刘松青. 四川泡菜可培养微生物菌群的研究.中国调味品, 2015, 40(12): 64–68.DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1000-9973.2015.12.015. |

| [30] | Chen G, Zhang QS, Yu WH, Liu Z, Li H, You JG. Analysis of volatile compounds and determination of key odors in Sichuan Paocai (Part Ⅱ).China Brewing, 2010, 35(12): 19–23(in Chinese) 陈功, 张其圣, 余文华, 刘竹, 李恒, 游敬刚. 四川泡菜挥发性成分及主体风味物质的研究(二).中国酿造, 2010, 35(12): 19–23.DOI:10.3969/j.issn.0254-5071.2010.12.006. |

| [31] | Zhu Y, Tramper J. Koji-where East meets West in fermentation.Biotechnology Advances, 2013, 31(8): 1448–1457DOI:10.1016/j.biotechadv.2013.07.001. |

| [32] | Li P, Lin W, Liu X, Wang X, Luo L. Environmental factors affecting microbiota dynamics during traditional solid-state fermentation of Chinese Daqu starter.Food Microbiology, 2016, 7: 1237 |

| [33] | Lü XG, Jia RB, Li Y, Chen F, Chen ZC, Liu B, Chen SJ, Rao PF, Ni L. Characterization of the dominant bacterial communities of traditional fermentation starters for Hong Qu glutinous rice wine by means of MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry fingerprinting, 16S rRNA gene sequencing and species-specific PCRs.Food Control, 2016, 67: 292–302DOI:10.1016/j.foodcont.2016.03.005. |

| [34] | Wang HY, Gao YB, Fan QW, Xu Y. Characterization and comparison of microbial community of different typical Chinese liquor Daqus by PCR-DGGE.Letters in Applied Microbiology, 2011, 53(2): 134–140DOI:10.1111/lam.2011.53.issue-2. |

| [35] | Zhang X, Zhao J, Du X. Barcoded pyrosequencing analysis of the bacterial community of Daqu for light-flavour Chinese liquor.Letters in Applied Microbiology, 2014, 58(6): 549–555DOI:10.1111/lam.2014.58.issue-6. |

| [36] | Wang HY, Xu Y. Effect of temperature on microbial composition of starter culture for Chinese light aroma style liquor fermentation.Letters in Applied Microbiology, 2015, 60(1): 85–91DOI:10.1111/lam.2014.60.issue-1. |

| [37] | Zheng XW, Tabrizi MR, Nout MJR, Han BZ. Daqu-a traditional Chinese liquor fermentation starter.Journal of the Institute of Brewing, 2011, 117(1): 82–90DOI:10.1002/(ISSN)2050-0416. |

| [38] | Chen B, Wu Q, Xu Y. Filamentous fungal diversity and community structure associated with the solid state fermentation of Chinese Maotai-flavor liquor.International Journal of Food Microbiology, 2014, 179: 80–84DOI:10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2014.03.011. |

| [39] | Zheng XW, Yan Z, Nout MJ, Smid EJ, Zwietering MH, Boekhout T, Han JS, Han BZ. Microbiota dynamics related to environmental conditions during the fermentative production of Fen-Daqu, a Chinese industrial fermentation starter.International Journal of Food Microbiology, 2014(182/183): 57–62 |

| [40] | Li P, Lin W, Liu X, Wang X, Gan X, Luo L, Lin WT. Effect of bioaugmented inoculation on microbiota dynamics during solid-state fermentation of Daqu starter using autochthonous of Bacillus, Pediococcus, Wickerhamomyces and Saccharomycopsis.Food Microbiology, 2017, 61: 83–92DOI:10.1016/j.fm.2016.09.004. |

| [41] | Li XR, Ma EB, Yan LZ, Meng H, Du XW, Quan ZX. Bacterial and fungal diversity in the starter production process of Fen liquor, a traditional Chinese liquor.Journal of Microbiology, 2013, 51(4): 430–438DOI:10.1007/s12275-013-2640-9. |

| [42] | Wu JJ, Ma YK, Zhang FF, Chen FS. Biodiversity of yeasts, lactic acid bacteria and acetic acid bacteria in the fermentation of "Shanxi aged vinegar", a traditional Chinese vinegar.Food Microbiology, 2012, 30(1): 289–297DOI:10.1016/j.fm.2011.08.010. |

| [43] | Tamang JP, Shin DH, Jung SJ, Chae SW. Functional properties of microorganisms in fermented foods.Frontiers in Microbiology, 2016, 7: 578 |

| [44] | Wu Q, Zhu W, Wang W, Xu Y. Effect of yeast species on the terpenoids profile of Chinese light-style liquor.Food Chemistry, 2015, 168: 390–395DOI:10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.07.069. |

| [45] | Kong Y, Wu Q, Zhang Y, Xu Y. In situ analysis of metabolic characteristics reveals the key yeast in the spontaneous and solid-state fermentation process of Chinese light-style liquor.Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2014, 80(12): 3667–3676DOI:10.1128/AEM.04219-13. |

| [46] | Shao MK, Wang HY, Xu Y, Nie Y. Yeast community structure and its impact on flavor components during the fermentation process of Chinese Maotai-flavor liquor.Microbiology China, 2014, 41(12): 2466–2473(in Chinese) 邵明凯, 王海燕, 徐岩, 聂尧. 酱香型白酒发酵中酵母群落结构及其对风味组分的影响.微生物学通报, 2014, 41(12): 2466–2473. |

| [47] | Wu Q, Kong Y, Xu Y. Flavor profile of Chinese liquor is altered by interactions of intrinsic and extrinsic microbes.Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2016, 82(2): 422–430DOI:10.1128/AEM.02518-15. |

| [48] | Lu ZM, Liu N, Wang LJ, Wu LH, Gong JS, Yu YJ, Li GQ, Shi JS, Xu ZH. Elucidating and regulating the acetoin production role of microbial functional groups in multispecies acetic acid fermentation.Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2016, 82(19): 5860–5868DOI:10.1128/AEM.01331-16. |

| [49] | Bokulich NA, Bergsveinson J, Ziola B, Mills DA. Mapping microbial ecosystems and spoilage-gene flow in breweries highlights patterns of contamination and resistance.eLife, 2015, 4(4): 4364–4366 |

| [50] | Roldán AM, Lloret I, Palacios V. Use of a submerged yeast culture and lysozyme for the treatment of bacterial contamination during biological aging of sherry wines.Food Control, 2017, 71: 42–49DOI:10.1016/j.foodcont.2016.06.016. |

| [51] | Zhang R, Wu Q, Xu Y. Aroma characteristics of Moutai-flavour liquor produced with Bacillus licheniformis by solid-state fermentation.Letters in Applied Microbiology, 2013, 57(1): 11–18DOI:10.1111/lam.12087. |

| [52] | Zhu BF, Xu Y, Fan WL. Tetramethylpyrazine production by fermentative conversion of endogenous precursor from glucose by Bacillus sp.Journal of Bioscience and Bioengineering, 2009, 108: S122–S122 |

| [53] | Hu XL, Du H, Xu Y. Identification and quantification of the caproic acid-producing bacterium Clostridium kluyveri in the fermentation of pit mud used for Chinese strong-aroma type liquor production.International Journal of Food Microbiology, 2015, 214: 116–122DOI:10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2015.07.032. |

| [54] | Tao Y, Hu X, Zhu X, Jin H, Xu Z, Tang Q, Li X. Production of butyrate from lactate by a newly isolated Clostridium sp. BPY5.Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology, 2016, 179(3): 361–374DOI:10.1007/s12010-016-1999-6. |

| [55] | Cleveland J, Montville TJ, Nes IF, Chikindas ML. Bacteriocins:safe, natural antimicrobials for food preservation.International Journal of Food Microbiology, 2001, 71(1): 1–20DOI:10.1016/S0168-1605(01)00560-8. |

| [56] | Jiao J, Zhang L, Yi H. Isolation and characterization of lactic acid bacteria from fresh Chinese traditional rice wines using denaturing gradient gel electrophoresis.Food Science and Biotechnology, 2016, 25(1): 173–178DOI:10.1007/s10068-016-0026-6. |

| [57] | Zhang WX, Qiao ZW, Shigematsu T, Tang YQ, Hu C, Morimura S, Kida K. Analysis of the bacterial community in Zaopei during production of Chinese Luzhou-flavor liquor.Journal of the Institute of Brewing, 2005, 111(2): 215–222DOI:10.1002/jib.2005.111.issue-2. |

| [58] | Nie Z, Zheng Y, Du H, Xie S, Wang M. Dynamics and diversity of microbial community succession in traditional fermentation of Shanxi aged vinegar.Food Microbiology, 2015, 47: 62–68DOI:10.1016/j.fm.2014.11.006. |

| [59] | Cizeikiene D, Juodeikiene G, Paskevicius A, Bartkiene E. Antimicrobial activity of lactic acid bacteria against pathogenic and spoilage microorganism isolated from food and their control in wheat bread.Food Control, 2013, 31(2): 539–545DOI:10.1016/j.foodcont.2012.12.004. |

| [60] | Arques JL, Rodriguez E, Langa S, Landete JM, Medina M. Antimicrobial activity of lactic acid bacteria in dairy products and gut:effect on pathogens.BioMed Research International, 2015, 2015: 584183 |

| [61] | Patel A, Shah N, Ambalam P, Prajapati JB, Holst O, Ljungh A. Antimicrobial profile of lactic acid bacteria isolated from vegetables and indigenous fermented foods of India against clinical pathogens using microdilution method.Biomedical and Environmental Sciences, 2013, 26(9): 759–764 |

| [62] | Zhang L, Wu C, Ding X, Zheng J, Zhou R. Characterisation of microbial communities in Chinese liquor fermentation starters Daqu using nested PCR-DGGE.World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology, 2014, 30(12): 3055–3063DOI:10.1007/s11274-014-1732-y. |

| [63] | 张亚丽. 贵州省仁怀地区茅台空气微生物的鉴定与分析. 北京化工大学硕士学位论文, 2014. |

| [64] | Tao Y, Li J, Rui J, Xu Z, Zhou Y, Hu X, Wang X, Liu M, Li D, Li X. Prokaryotic communities in pit mud from different-aged cellars used for the production of Chinese strong-flavored liquor.Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2014, 80(7): 2254–2260DOI:10.1128/AEM.04070-13. |

| [65] | Zhang L, Zhou R, Niu M, Zheng J, Wu C. Difference of microbial community stressed in artificial pit muds for Luzhou-flavour liquor brewing revealed by multiphase culture-independent technology.Journal of Applied Microbiology, 2015, 119(5): 1345–1356DOI:10.1111/jam.2015.119.issue-5. |

| [66] | Hu XL, Du H, Ren C, Xu Y. Illuminating anaerobic microbial community and cooccurrence patterns across a quality gradient in Chinese liquor fermentation pit muds.Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2016, 82(8): 2506–2515DOI:10.1128/AEM.03409-15. |

| [67] | Luo Q, Liu C, Wu Z, Wang H, Li W, Zhang K, Huang D, Zhang J, Zhang W. Monitoring of the prokaryotic diversity in pit mud from a Luzhou-flavour liquor distillery and evaluation of two predominant archaea using qPCR assays.Journal of the Institute of Brewing, 2014, 120(3): 253–261DOI:10.1002/jib.v120.3. |

| [68] | Porat I, Vishnivetskaya TA, Mosher JJ, Brandt CC, Yang ZK, Brooks SC, Liang L, Drake MM, Podar M, Brown SD, Palumbo AV. Characterization of archaeal community in contaminated and uncontaminated surface stream sediments.Microbial Ecology, 2010, 60(4): 784–795DOI:10.1007/s00248-010-9734-2. |

| [69] | Wu C, Ding X, Huang J, Zhou R. Characterization of archaeal community in Luzhou-flavour pit mud.Journal of the Institute of Brewing, 2015, 121(4): 597–602DOI:10.1002/jib.255. |

| [70] | Aydin S, Y?ld?r?m E, Ince O, Ince B. Rumen anaerobic fungi create new opportunities for enhanced methane production from microalgae biomass.Algal Research, 2017, 23: 150–160DOI:10.1016/j.algal.2016.12.016. |

| [71] | Dollhofer V, Podmirseg SM, Callaghan TM, Griffith GW, Fliegerová K. Biogas Science and Technology.Springer International Publishing, 2015: 41-61. |

| [72] | Foo JL, Ling H, Lee YS, Chang MW. Microbiome engineering:current applications and its future.Biotechnology Journal, 2017, 12(3): 1600099DOI:10.1002/biot.v12.3. |

| [73] | Wu Q, Ling J, Xu Y. Starter culture selection for making Chinese sesame-flavored liquor based on microbial metabolic activity in mixed-culture fermentation.Applied and Environmental Microbiology, 2014, 80(14): 4450–4459DOI:10.1128/AEM.00905-14. |

| [74] | Wang HY, Tang J, Xu Y, Liu YC, Yang Q, Wang Z, Yang SZ, Li YQ, Li RL, Guan Y. Analysis of community structure of microbes and functional microbes in fen-flavor xiaoqu liquor.Liquor-Making Science & Technology, 2012, 12: 48–52(in Chinese) 王海燕, 唐洁, 徐岩, 刘源才, 杨强, 王喆, 杨生智, 李燕群, 李锐利, 管莹. 清香型小曲白酒中微生物组成及功能微生物的分析.酿酒科技, 2012, 12: 48–52. |

| [75] | Xu Y. Study on liquor-making microbes and the regulation & control of their metabolism based on flavor-oriented technology.Liquor-Making Science & Technology, 2015, 2(2): 1–11-16(in Chinese) 徐岩. 基于风味导向技术的中国白酒微生物及其代谢调控研究.酿酒科技, 2015, 2(2): 1–11-16. |

| [76] | Bing J, Han PJ, Liu WQ, Wang QM, Bai FY. Evidence for a Far East Asian origin of lager beer yeast.Current Biology, 2014, 24(10): R380–381DOI:10.1016/j.cub.2014.04.031. |

| [77] | Hittinger CT, Rokas A, Bai FY, Boekhout T, Goncalves P, Jeffries TW, Kominek J, Lachance MA, Libkind D, Rosa CA, Sampaio JP, Kurtzman CP. Genomics and the making of yeast biodiversity.Current Opinion in Genetics & Development, 2015, 35: 100–109 |

| [78] | Yu XW, Wang LL, Xu Y. Rhizopus chinensis lipase:Gene cloning, expression in Pichia pastoris and properties.Journal of Molecular Catalysis B-Enzymatic, 2009, 57(1-4): 304–311DOI:10.1016/j.molcatb.2008.10.002. |

| [79] | Lu X, Wu Q, Zhang Y, Xu Y. Genomic and transcriptomic analyses of the Chinese Maotai-flavored liquor yeast MT1 revealed its unique multi-carbon co-utilization.BMC Genomics, 2015, 16: 1064DOI:10.1186/s12864-015-2263-0. |

| [80] | Wu Q, Xu Y, Chen L. Diversity of yeast species during fermentative process contributing to Chinese Maotai-flavour liquor making.Letters in Applied Microbiology, 2012, 55(4): 301–307DOI:10.1111/lam.2012.55.issue-4. |

| [81] | Zhi Y, Wu Q, Xu Y. Genome and transcriptome analysis of surfactin biosynthesis in Bacillus amyloliquefaciens MT45.Scientific Reports, 2017, 7: 40976DOI:10.1038/srep40976. |

| [82] | Ge J, Sun Y, Xin X, Wang Y, Ping W. Purification and partial characterization of a novel bacteriocin synthesized by Lactobacillus paracasei HD1-7 isolated from Chinese Sauerkraut juice.Scientific Reports, 2016, 6: 19366DOI:10.1038/srep19366. |