1 杭州师范大学认知与脑疾病研究中心

2 杭州师范大学心理科学研究院, 杭州 311121

3 浙江省认知障碍评估技术研究重点实验室, 杭州 311121

4 Institute of Mental Health Research, University of Ottawa, Ottawa K1Z7K4, Canada

收稿日期:2017-10-09出版日期:2019-01-25发布日期:2018-11-26通讯作者:胡治国基金资助:* 国家自然科学基金面上项目资助(31271195)Future thinking in non-clinical depression: the relevance of personal goals

HU Zhiguo1,2,3,*, CHEN Jing1,2, WU Huijun1,2, Georg Northoff1,2,3,41 Center for Cognition and Brain Disorders, Hangzhou Normal University, Hangzhou 311121, China

2 Institutes of Psychological Sciences, Hangzhou Normal University, Hangzhou 311121, China

3 Zhejiang Key Laboratory for Research in Assessment of Cognitive Impairments, Hangzhou 311121, China

4 Institute of Mental Health Research, University of Ottawa, Ottawa K1Z7K4, Canada

Received:2017-10-09Online:2019-01-25Published:2018-11-26Contact:HU Zhiguo 摘要/Abstract

摘要: 通过两个实验考查了非临床抑郁者未来想象的异常是否受到个人目标相关性的调节。实验1采用未来想象任务, 实验2采用可能性评估范式, 两个实验一致发现, 抑郁倾向者想象未来积极事件的异常, 受到了与个人目标相关性的调节:相对于非抑郁倾向者, 抑郁倾向者对未来与个人目标相关的积极事件的预期减弱, 而对未来与个人目标无关的积极事件的预期则没有表现出异常; 同时还发现, 抑郁倾向者表现出了对未来消极预期的普遍增强, 不受与个人目标相关性的影响。

图/表 5

表1被试想象到的未来事件的个数及事件评估的结果

| 事件类型 | 抑郁组 (N = 23) | 非抑郁组 (N = 25) | p值 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 与个人目标相关的积极事件 | |||

| 想象的个数 | 5.4 (1.9) | 6.7 (2.1) | 0.036 |

| 发生的可能性 | 32.5 (8.1) | 40.4 (6.1) | 0.000 |

| 与个人目标的相关性 | 42.9 (7.2) | 43.8 (7.1) | 0.685 |

| 可能的情绪反应 | 37.4 (16.4) | 40.3 (9.3) | 0.450 |

| 与个人目标相关的消极事件 | |||

| 想象的个数 | 4.9 (1.7) | 5.1 (2.5) | 0.789 |

| 发生的可能性 | 27.0 (8.7) | 21.5 (8.8) | 0.036 |

| 与个人目标的相关性 | 41.0 (8.0) | 39.4 (9.9) | 0.525 |

| 可能的情绪反应 | -25.4 (21.4) | -29.1 (21.4) | 0.445 |

| 与个人目标无关的积极事件 | |||

| 想象的个数 | 5.3 (2.1) | 5.4 (1.9) | 0.867 |

| 发生的可能性 | 34.4 (9.0) | 36.0 (9.6) | 0.560 |

| 与个人目标的相关性 | 18.9 (11.3) | 19.8 (14.1) | 0.802 |

| 可能的情绪反应 | 24.6 (13.0) | 22.9 (11.9) | 0.639 |

| 与个人目标无关的消极事件 | |||

| 想象的个数 | 5.0 (2.3) | 5.0 (2.0) | 0.996 |

| 发生的可能性 | 28.2 (9.8) | 25.8 (9.9) | 0.404 |

| 与个人目标的相关性 | 14.8 (10.6) | 18.6 (15.2) | 0.317 |

| 可能的情绪反应 | -16.0 (12.1) | -11.4 (10.1) | 0.154 |

表1被试想象到的未来事件的个数及事件评估的结果

| 事件类型 | 抑郁组 (N = 23) | 非抑郁组 (N = 25) | p值 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 与个人目标相关的积极事件 | |||

| 想象的个数 | 5.4 (1.9) | 6.7 (2.1) | 0.036 |

| 发生的可能性 | 32.5 (8.1) | 40.4 (6.1) | 0.000 |

| 与个人目标的相关性 | 42.9 (7.2) | 43.8 (7.1) | 0.685 |

| 可能的情绪反应 | 37.4 (16.4) | 40.3 (9.3) | 0.450 |

| 与个人目标相关的消极事件 | |||

| 想象的个数 | 4.9 (1.7) | 5.1 (2.5) | 0.789 |

| 发生的可能性 | 27.0 (8.7) | 21.5 (8.8) | 0.036 |

| 与个人目标的相关性 | 41.0 (8.0) | 39.4 (9.9) | 0.525 |

| 可能的情绪反应 | -25.4 (21.4) | -29.1 (21.4) | 0.445 |

| 与个人目标无关的积极事件 | |||

| 想象的个数 | 5.3 (2.1) | 5.4 (1.9) | 0.867 |

| 发生的可能性 | 34.4 (9.0) | 36.0 (9.6) | 0.560 |

| 与个人目标的相关性 | 18.9 (11.3) | 19.8 (14.1) | 0.802 |

| 可能的情绪反应 | 24.6 (13.0) | 22.9 (11.9) | 0.639 |

| 与个人目标无关的消极事件 | |||

| 想象的个数 | 5.0 (2.3) | 5.0 (2.0) | 0.996 |

| 发生的可能性 | 28.2 (9.8) | 25.8 (9.9) | 0.404 |

| 与个人目标的相关性 | 14.8 (10.6) | 18.6 (15.2) | 0.317 |

| 可能的情绪反应 | -16.0 (12.1) | -11.4 (10.1) | 0.154 |

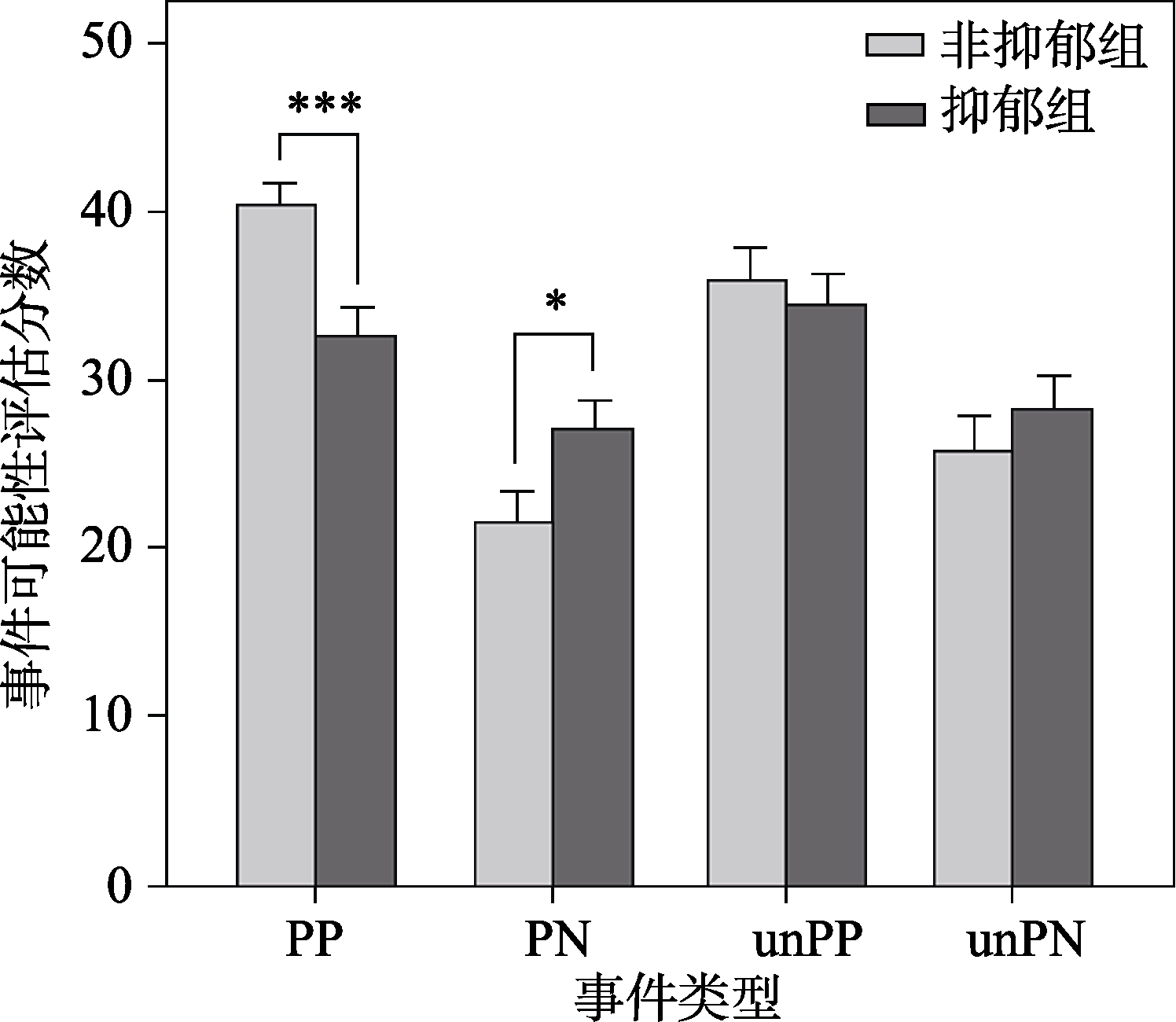

图1抑郁组和非抑郁组想象到的不同类型未来事件的个数 注:PP代表与个人目标相关的积极事件(personal goal-related positive); PN代表与个人目标相关的消极事件(personal goal-related negative); unPP代表与个人目标无关的积极事件(personal goal-unrelated positive); unPN代表与个人目标无关的消极事件(personal goal-unrelated negative)。* p < 0.05。

图1抑郁组和非抑郁组想象到的不同类型未来事件的个数 注:PP代表与个人目标相关的积极事件(personal goal-related positive); PN代表与个人目标相关的消极事件(personal goal-related negative); unPP代表与个人目标无关的积极事件(personal goal-unrelated positive); unPN代表与个人目标无关的消极事件(personal goal-unrelated negative)。* p < 0.05。

图1抑郁组和非抑郁组想象到的不同类型未来事件的个数 注:PP代表与个人目标相关的积极事件(personal goal-related positive); PN代表与个人目标相关的消极事件(personal goal-related negative); unPP代表与个人目标无关的积极事件(personal goal-unrelated positive); unPN代表与个人目标无关的消极事件(personal goal-unrelated negative)。* p < 0.05。

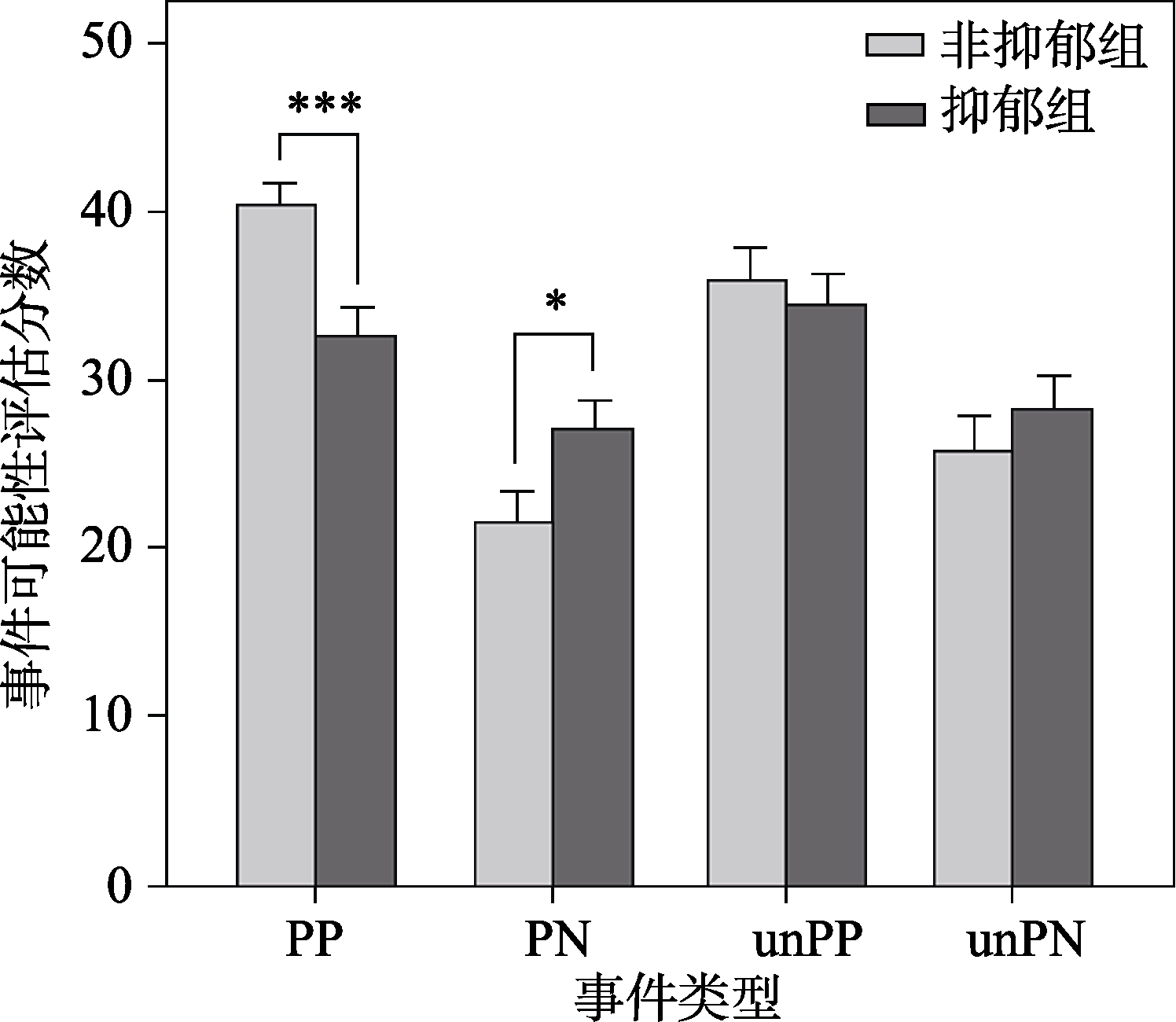

图2抑郁组和非抑郁组对想象到的未来事件发生可能性评估的直接对比 注: * p < 0.05, *** p < 0.001。

图2抑郁组和非抑郁组对想象到的未来事件发生可能性评估的直接对比 注: * p < 0.05, *** p < 0.001。

图2抑郁组和非抑郁组对想象到的未来事件发生可能性评估的直接对比 注: * p < 0.05, *** p < 0.001。表2未来事件的可能性、与个人目标的相关性和情绪反应的评估结果

| 事件类型 | 抑郁组 (N = 27) | 非抑郁组 (N = 29) | p值 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 与个人目标相关的积极事件 | |||

| 发生的可能性 | 35.0 (7.6) | 39.8 (5.3) | 0.007 |

| 与个人目标的相关性 | 40.3 (8.3) | 43.2 (5.2) | 0.121 |

| 可能的情绪反应 | 42.0 (7.6) | 43.8 (6.7) | 0.357 |

| 与个人目标相关的消极事件 | |||

| 发生的可能性 | 26.1 (6.9) | 16.2 (4.7) | 0.000 |

| 与个人目标的相关性 | 32.3 (10.7) | 36.8 (10.8) | 0.128 |

| 可能的情绪反应 | -24.7 (9.8) | -25.3 (10.7) | 0.823 |

| 与个人目标无关的积极事件 | |||

| 发生的可能性 | 33.3 (6.7) | 33.8 (6.8) | 0.774 |

| 与个人目标的相关性 | 22.0 (9.9) | 21.4 (9.8) | 0.815 |

| 可能的情绪反应 | 26.4 (8.8) | 25.2 (8.6) | 0.593 |

| 与个人目标无关的消极事件 | |||

| 发生的可能性 | 28.1 (6.0) | 22.2 (6.0) | 0.001 |

| 与个人目标的相关性 | 17.9 (9.1) | 18.2 (7.6) | 0.904 |

| 可能的情绪反应 | -12.4 (7.2) | -10.8 (7.7) | 0.428 |

表2未来事件的可能性、与个人目标的相关性和情绪反应的评估结果

| 事件类型 | 抑郁组 (N = 27) | 非抑郁组 (N = 29) | p值 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 与个人目标相关的积极事件 | |||

| 发生的可能性 | 35.0 (7.6) | 39.8 (5.3) | 0.007 |

| 与个人目标的相关性 | 40.3 (8.3) | 43.2 (5.2) | 0.121 |

| 可能的情绪反应 | 42.0 (7.6) | 43.8 (6.7) | 0.357 |

| 与个人目标相关的消极事件 | |||

| 发生的可能性 | 26.1 (6.9) | 16.2 (4.7) | 0.000 |

| 与个人目标的相关性 | 32.3 (10.7) | 36.8 (10.8) | 0.128 |

| 可能的情绪反应 | -24.7 (9.8) | -25.3 (10.7) | 0.823 |

| 与个人目标无关的积极事件 | |||

| 发生的可能性 | 33.3 (6.7) | 33.8 (6.8) | 0.774 |

| 与个人目标的相关性 | 22.0 (9.9) | 21.4 (9.8) | 0.815 |

| 可能的情绪反应 | 26.4 (8.8) | 25.2 (8.6) | 0.593 |

| 与个人目标无关的消极事件 | |||

| 发生的可能性 | 28.1 (6.0) | 22.2 (6.0) | 0.001 |

| 与个人目标的相关性 | 17.9 (9.1) | 18.2 (7.6) | 0.904 |

| 可能的情绪反应 | -12.4 (7.2) | -10.8 (7.7) | 0.428 |

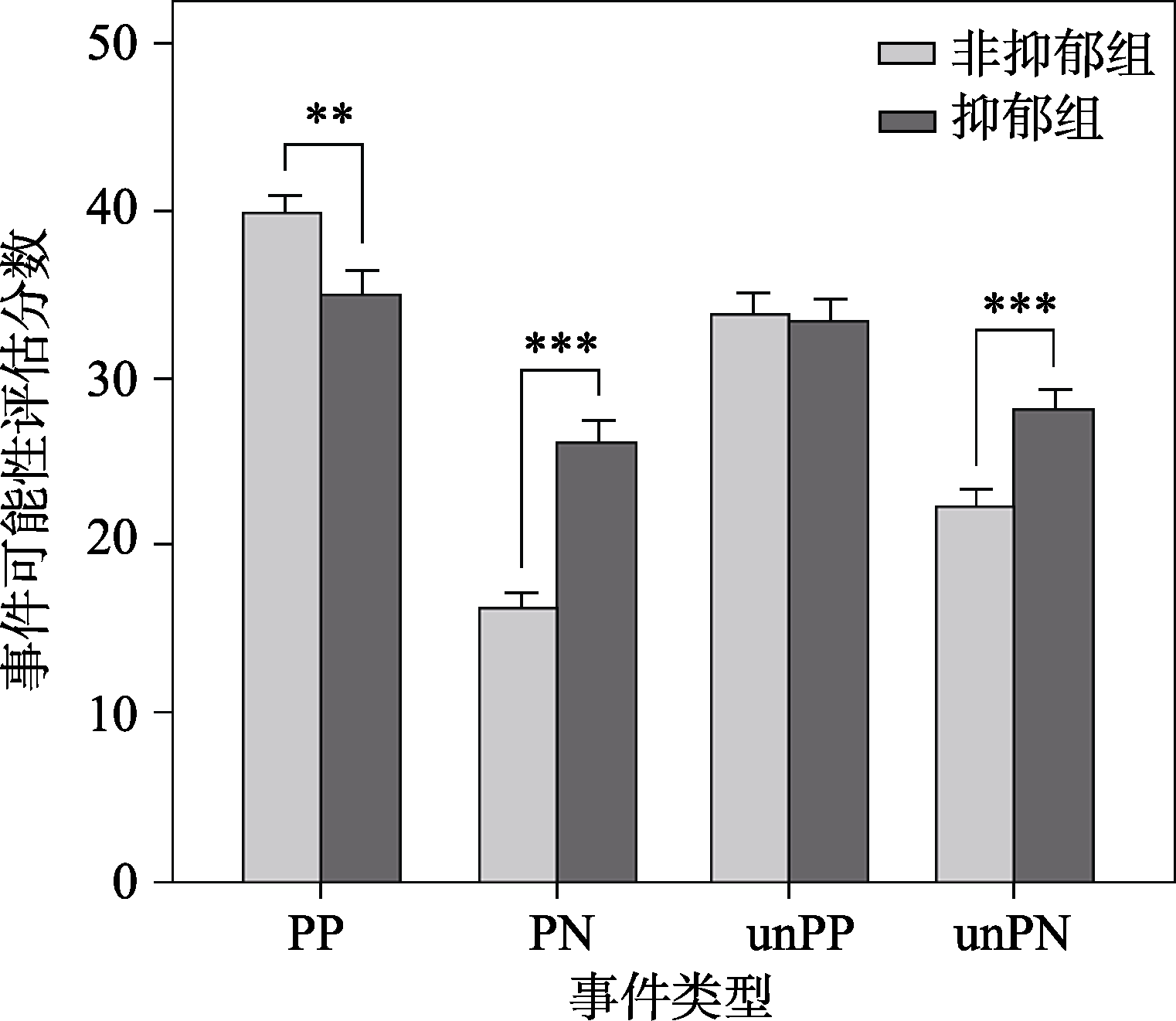

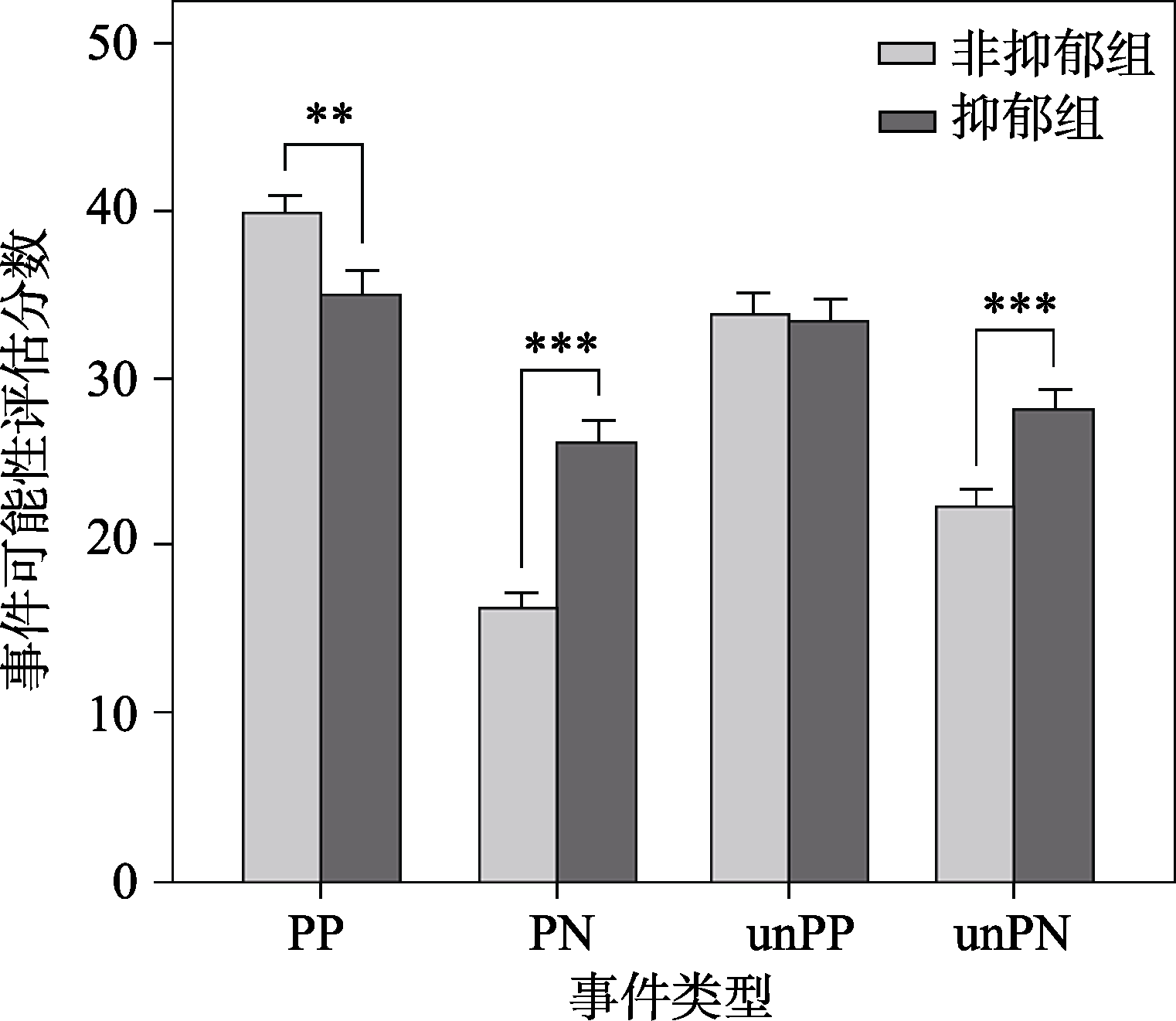

图3抑郁组和非抑郁组对给定的不同类型未来事件发生可能性评估的直接对比 注:** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001。

图3抑郁组和非抑郁组对给定的不同类型未来事件发生可能性评估的直接对比 注:** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001。

图3抑郁组和非抑郁组对给定的不同类型未来事件发生可能性评估的直接对比 注:** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001。参考文献 52

| [1] | Abramson L. Y., Metalsky G. L., & Alloy L. B . ( 1989). Hopelessness depression: A theory-based subtype of depression. Psychological Review, 96( 2), 358-372. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.96.2.358URL |

| [2] | Andersson G., Sarkohi A., Karlsson J., Bj?rehed J., & Hesser H . ( 2013). Effects of two forms of internet-delivered cognitive behaviour therapy for depression on future thinking. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 37( 1), 29-34. doi: 10.1007/s10608-012-9442-yURL |

| [3] | Atance C.M., & O’Neill D.K . ( 2001). Episodic future thinking. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 5( 12), 533-539. doi: 10.1016/S1364-6613(00)01804-0URL |

| [4] | Barsics C., Van der Linden M., & D'Argembeau A . ( 2016). Frequency, characteristics, and perceived functions of emotional future thinking in daily life. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 69( 2), 217-233. doi: 10.1080/17470218.2015.1051560URLpmid: 26140455 |

| [5] | Beck A. T., Rush A. J., Shaw B. F.& Emery G.. ,( 1979) . Cognitive Therapy of Depression. New York: Guilford Press. |

| [6] | Beck A. T., Wenzel A., Riskind J. H., Brown G., & Steer R. A . ( 2006). Specificity of hopelessness about resolving life problems: Another test of the cognitive model of depression. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 30( 6), 773-781. doi: 10.1007/s10608-006-9081-2URL |

| [7] | Bj?rehed J., Sarkohi A., & Andersson G . ( 2010). Less positive or more negative? Future-directed thinking in mild to moderate depression. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 39( 1), 37-45. doi: 10.1080/16506070902966926URLpmid: 19714541 |

| [8] | Bouwman V. . ( 2016). The relationship between depression and different types of positive future goals cross-sectionally and over time (Unpublished master's thesis). Utrecht University. |

| [9] | Brown G. P., Macleod A. K., Tata P., & Goddard L . ( 2002). Worry and the simulation of future outcomes. Anxiety, Stress & Coping, 15( 1), 1-17. doi: 10.1080/10615800290007254URL |

| [10] | Christian B. M., Miles L. K., Fung F. H. K., Best S., & Macrae C. N . ( 2013). The shape of things to come: Exploring goal-directed prospection. Consciousness and Cognition, 22( 2), 471-478. doi: 10.1016/j.concog.2013.02.002URLpmid: 23499995 |

| [11] | Cordonnier A., Barnier A. J., & Sutton J . ( 2016). Scripts and information units in future planning: Interactions between a past and a future planning task. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 69( 2), 324-338. doi: 10.1080/17470218.2015.1085587URLpmid: 26308675 |

| [12] | D'Argembeau A. (2015). Knowledge structures involved in episodic future thinking. In A. Feeney & V. A. Thompson (Eds, ), Reasoning as memory (pp. 128-145). Hove,UK: Psychology Press. |

| [13] | D'Argembeau A., Lardi C& Van der Linden, M. ., ( 2012). Self-defining future projections: Exploring the identity function of thinking about the future. Memory. 20( 2), 110-120. doi: 10.1080/09658211.2011.647697URLpmid: 22292616 |

| [14] | D'Argembeau A., Stawarczyk D., Majerus S., Collette F., Van der Linden M., Feyers D., … Salmon E . ( 2010). The neural basis of personal goal processing when envisioning future events. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 22( 8), 1701-1713. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2009.21314URLpmid: 19642887 |

| [15] | Feeser M., Schlagenhauf F., Sterzer P., Park S., Stoy M., Gutwinski S., … Bermpohl F . ( 2013). Context insensitivity during positive and negative emotional expectancy in depression assessed with functional magnetic resonance imaging. Psychiatry Research: Neuroimaging, 212( 1), 28-35. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2012.11.010URLpmid: 23473989 |

| [16] | Flett G. L., Vredenburg K., & Krames L . ( 1997). The continuity of depression in clinical and nonclinical samples. Psychological Bulletin, 121( 3), 395-416. doi: 10.1037//0033-2909.121.3.395URLpmid: 9136642 |

| [17] | Hill A. B., Kemp-Wheeler S. M., & Jones S. A . ( 1987). Subclinical and clinical depression: Are analogue studies justifiable?. Personality and Individual Differences, 8( 1), 113-120. doi: 10.1016/0191-8869(87)90017-1URL |

| [18] | Hoerger M., Quirk S. W., Chapman B. P., & Duberstein P. R . ( 2012). Affective forecasting and self-rated symptoms of depression, anxiety, and hypomania: Evidence for a dysphoric forecasting bias. Cognition & Emotion, 26( 6), 1098-1106. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2011.631985URLpmid: 22397734 |

| [19] | Ji J. L., Holmes E. A., & Blackwell S. E . ( 2017). Seeing light at the end of the tunnel: Positive prospective mental imagery and optimism in depression. Psychiatry Research, 247, 155-162. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.11.025URLpmid: 5241224 |

| [20] | Korn C. W., Sharot T., Walter H., Heekeren H. R., & Dolan R. J . ( 2014). Depression is related to an absence of optimistically biased belief updating about future life events. Psychological Medicine, 44( 3), 579-592. doi: 10.1017/S0033291713001074URLpmid: 23672737 |

| [21] | Kosnes L., Whelan R., O’Donovan A., & McHugh L. A . ( 2013). Implicit measurement of positive and negative future thinking as a predictor of depressive symptoms and hopelessness. Consciousness and Cognition, 22( 3), 898-912. doi: 10.1016/j.concog.2013.06.001URLpmid: 23810864 |

| [22] | Lu A. T., Zhang J. J., & Mo L . ( 2008). The impact of attentional control and short-term storage on phonemic and semantic fluency. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 40( 1), 25-36. |

| [ 陆爱桃, 张积家, 莫雷 . ( 2008). 注意控制和短时存储对音位流畅性和语义流畅性的影响. 心理学报, 40( 1), 25-36.] | |

| [23] | Macleod A. ( 2017). Prospection, well-being, and mental health. Oxford: Oxford University Press. |

| [24] | MacLeod A.K., & Byrne A. , ( 1996). Anxiety, depression, and the anticipation of future positive and negative experiences. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 105( 2), 286-289. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.105.2.286URLpmid: 8723011 |

| [25] | MacLeod A.K., & Conway C. , ( 2007). Well-being and positive future thinking for the self versus others. Cognition and Emotion, 21( 5), 1114-1124. doi: 10.1080/02699930601109507URL |

| [26] | MacLeod A.K., & Cropley M.L . ( 1995). Depressive future-thinking: The role of valence and specificity. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 19( 1), 35-50. doi: 10.1007/BF02229675URL |

| [27] | MacleodA. A.K., & Moore R. , ( 2000). Positive thinking revisited: Positive cognitions, well-being and mental health. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 7( 1), 1-10. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-0879(200002)7:13.0.CO;2-SURL |

| [28] | MacLeod A. K., Pankhania B., Lee M., & Mitchell D . ( 1997). Parasuicide, depression and the anticipation of positive and negative future experiences. Psychological Medicine, 27( 4), 973-977. doi: 10.1017/S003329179600459XURLpmid: 9234475 |

| [29] | MacLeod A. K., Rose G. S& Williams J. M. G. ., ( 1993). Components of hopelessness about the future in parasuicide. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 17( 5), 441-455. doi: 10.1007/BF01173056URL |

| [30] | MacLeod A.K., & Salaminiou E. ,( 2001). Reduced positive future-thinking in depression: Cognitive and affective factors. Cognition and Emotion, 15( 1), 99-107. doi: 10.1080/02699930125776URL |

| [31] | MacLeod A. K., Tata P., Evans K., Tyrer P., Schmidt U., Davidson K., … Catalan J . ( 1998). Recovery of positive future thinking within a high-risk parasuicide group: Results from a pilot randomized controlled trial. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 37( 4), 371-379. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1998.tb01394.xURLpmid: 9856290 |

| [32] | MacLeod A. K., Tata P., Kentish J., Carroll F., & Hunter E . ( 1997). Anxiety, depression, and explanation-based pessimism for future positive and negative events. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 4( 1), 15-24. |

| [33] | MacLeod A. K., Tata P., Kentish J., & Jacobsen H . ( 1997). Retrospective and prospective cognitions in anxiety and depression. Cognition & Emotion, 11( 4), 467-479. doi: 10.1080/026999397379881URL |

| [34] | Miles H., MacLeod A. K., & Pote H . ( 2004). Retrospective and prospective cognitions in adolescents: Anxiety, depression, and positive and negative affect. Journal of Adolescence, 27( 6), 691-701. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2004.04.001URLpmid: 15561311 |

| [35] | Miranda R., & Mennin D.S . ( 2007). Depression, generalized anxiety disorder, and certainty in pessimistic predictions about the future. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 31( 1), 71-82. doi: 10.1007/s10608-006-9063-4URL |

| [36] | Neroni M. A., Gamboz N., de Vito S., & Brandimonte M. A . ( 2016). Effects of self-generated versus experimenter- provided cues on the representation of future events. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology. 69( 9), 1799-1811. doi: 10.1080/17470218.2015.1100205URLpmid: 26444043 |

| [37] | Pyszczynski T., Holt K., & Greenberg J . ( 1987). Depression, self-focused attention, and expectancies for positive and negative future life events for self and others. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52( 5), 994-1001. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.52.5.994URLpmid: 3585706 |

| [38] | Rasmussen K.W., & Berntsen D. , ( 2014). “I can see clearly now”: The effect of cue imageability on mental time travel. Memory & Cognition, 42( 7), 1063-1075. doi: 10.3758/s13421-014-0414-1URLpmid: 24874508 |

| [39] | Roepke A.M., & Seligman M. E.P . ( 2016). Depression and prospection. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 55( 1), 23-48. doi: 10.1111/bjc.12087URL |

| [40] | Sarkohi A. ( 2011). Future thinking and depression (Unpublished doctorial dissertation). Link?ping University. |

| [41] | Sarkohi A., Frykedal K., Forsyth H., Larsson S., & Andersson G . ( 2013). Representations of the future in depression—A qualitative study. Psychology, 4( 4), 420-426. |

| [42] | Schacter D.L., & Addis D.R . ( 2007). The cognitive neuroscience of constructive memory: Remembering the past and imagining the future. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, Series B, Biological Sciences, 362( 1481), 773-786. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2007.2087URLpmid: 2429996 |

| [43] | Seligman M., Railton P., Baumeister R., & Sripada C . ( 2013). Navigating into the future or driven by the past. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 8( 2), 119-141. doi: 10.1177/1745691612474317URL |

| [44] | Stawarczyk D.& D'Argembeau A. , ( 2015). Neural correlates of personal goal processing during episodic future thinking and mind-wandering: An ALE meta-analysis. Human Brain Mapping. 36( 8), 2928-2947. doi: 10.1002/hbm.22818URLpmid: 25931002 |

| [45] | Strunk D. R., Lopez H., & DeRubeis R. J . ( 2006). Depressive symptoms are associated with unrealistic negative predictions of future life events. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44( 6), 861-882. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.07.001URLpmid: 16126162 |

| [46] | Sz?ll?si á Pajkossy P& Racsmány M. , ( 2015). Depressive symptoms are associated with the phenomenal characteristics of imagined positive and negative future events. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 29( 5), 762-767. doi: 10.1002/acp.3144URL |

| [47] | Szpunar K.K., & Schacter D.L . ( 2013). Get real: Effects of repeated simulation and emotion on the perceived plausibility of future experiences. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 142( 2), 323-327. doi: 10.1037/a0028877URLpmid: 3461111 |

| [48] | Thimm J. C., Holte A., Brennen T& Wang C. E. A. ., ( 2013). Hope and expectancies for future events in depression. Frontiers in Psychology, 4, 470. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00470URLpmid: 3721024 |

| [49] | Vilhauer J. S., Young S., Kealoha C., Borrmann J., IsHak W. W., Rapaport M. H., … Mirocha J . ( 2012). Treating major depression by creating positive expectations for the future: A pilot study for the effectiveness of future-directed therapy (FDT) on symptom severity and quality of life. CNS Neuroscience & Therapeutics, 18( 2), 102-109. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5949.2011.00235.xURLpmid: 21615882 |

| [50] | Vincent P. J., Boddana P., & MacLeod A. K . ( 2004). Positive life goals and plans in parasuicide. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 11( 2), 90-99. doi: 10.1002/cpp.394URL |

| [51] | Vredenburg K., Flett G. L., & Krames L . ( 1993). Analogue versus clinical depression: A critical reappraisal. Psychological Bulletin, 113( 2), 327-344. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.113.2.327URLpmid: 8451338 |

| [52] | We?lau C.& Steil R. ,( 2014). Visual mental imagery in psychopathology—Implications for the maintenance and treatment of depression. Clinical Psychology Review, 34( 4), 273-281. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2014.03.001URLpmid: 24727643 |

相关文章 15

| [1] | 程瑞, 卢克龙, 郝宁. 愤怒情绪对恶意创造力的影响及调节策略[J]. 心理学报, 2021, 53(8): 847-860. |

| [2] | 宋琪, 陈扬. 需求和接受的授权型领导匹配对下属工作结果的影响:情绪耗竭的中介作用[J]. 心理学报, 2021, 53(8): 890-903. |

| [3] | 熊承清, 许佳颖, 马丹阳, 刘永芳. 囚徒困境博弈中对手面部表情对合作行为的影响及其作用机制[J]. 心理学报, 2021, 53(8): 919-932. |

| [4] | 袁加锦, 张祎程, 陈圣栋, 罗利, 茹怡珊. 中国情绪调节词语库的初步编制与试用[J]. 心理学报, 2021, 53(5): 445-455. |

| [5] | 宋锡妍, 程亚华, 谢周秀甜, 龚楠焰, 刘雷. 愤怒情绪对延迟折扣的影响:确定感和控制感的中介作用[J]. 心理学报, 2021, 53(5): 456-468. |

| [6] | 莫李澄, 郭田友, 张岳瑶, 徐锋, 张丹丹. 激活右腹外侧前额叶提高抑郁症患者对社会疼痛的情绪调节能力:一项TMS研究[J]. 心理学报, 2021, 53(5): 494-504. |

| [7] | 黄垣成, 赵清玲, 李彩娜. 青少年早期抑郁和自伤的联合发展轨迹:人际因素的作用[J]. 心理学报, 2021, 53(5): 515-526. |

| [8] | 杨伟文, 李超平. 资质过剩感对个体绩效的作用效果及机制:基于情绪-认知加工系统与文化情境的元分析[J]. 心理学报, 2021, 53(5): 527-554. |

| [9] | 侯娟, 朱英格, 方晓义. 手机成瘾与抑郁:社交焦虑和负性情绪信息注意偏向的多重中介作用[J]. 心理学报, 2021, 53(4): 362-373. |

| [10] | 刘宇平, 李姗珊, 何赟, 王豆豆, 杨波. 消除威胁或无能狂怒?自恋对暴力犯攻击的影响机制[J]. 心理学报, 2021, 53(3): 244-258. |

| [11] | 雷震, 毕蓉, 莫李澄, 于文汶, 张丹丹. 外显和内隐情绪韵律加工的脑机制:近红外成像研究[J]. 心理学报, 2021, 53(1): 15-25. |

| [12] | 黄月胜, 张豹, 范兴华, 黄杰. 无关工作记忆表征的负性情绪信息能否捕获视觉注意?一项眼动研究[J]. 心理学报, 2021, 53(1): 26-37. |

| [13] | 苗晓燕, 孙欣, 匡仪, 汪祚军. 共患难, 更同盟:共同经历相同负性情绪事件促进合作行为[J]. 心理学报, 2021, 53(1): 81-94. |

| [14] | 华艳, 李明霞, 王巧婷, 冯彩霞, 张晶. 左侧眶额皮层在自动情绪调节下注意选择中的作用:来自经颅直流电刺激的证据[J]. 心理学报, 2020, 52(9): 1048-1056. |

| [15] | 李树文, 罗瑾琏. 领导-下属情绪评价能力一致与员工建言:内部人身份感知与性别相似性的作用[J]. 心理学报, 2020, 52(9): 1121-1131. |

PDF全文下载地址:

http://journal.psych.ac.cn/xlxb/CN/article/downloadArticleFile.do?attachType=PDF&id=4360