,法国普瓦蒂埃大学,法国国家科研中心UMR 7262 普瓦蒂埃市 86073

,法国普瓦蒂埃大学,法国国家科研中心UMR 7262 普瓦蒂埃市 86073Taxonomic revision of Anthracokeryx thailandicus Ducrocq, 1999 (Anthracotheriidae, Microbunodontinae) from the Upper Eocene of Thailand

DUCROCQ Stéphane ,PALEVOPRIM, UMR 7262 CNRS, Université de Poitiers UFR SFA, 6 rue M. Brunet, TSA 51106, 86073 Poitiers cedex 9,France

,PALEVOPRIM, UMR 7262 CNRS, Université de Poitiers UFR SFA, 6 rue M. Brunet, TSA 51106, 86073 Poitiers cedex 9,France通讯作者: stephane.ducrocq@univ-poitiers.fr

收稿日期:2020-04-30网络出版日期:2020-10-20

| 基金资助: |

Corresponding authors: stephane.ducrocq@univ-poitiers.fr

Received:2020-04-30Online:2020-10-20

摘要

重新描述了泰国晚始新世石炭兽类(哺乳动物纲,鲸偶蹄类)的泰国先炭兽(Anthracokeryx thailandicus), 修订了该种在科内的系统发育位置。据观察,泰国标本具有一系列重要的牙齿差异,因而建立一新属颏炭兽(Geniokeryx gen. nov.), 代表了归入小丘齿兽亚科(Microbunodontinae)的第3个属。新属的主要特征是下颌联合短而深,未愈合;上、下前臼齿粗壮;上臼齿呈微弱新月型,具原附尖,无后小尖外棱。下颌联合的独特形态可能属于性双型特征,为雄性增大的上犬齿提供了侧面保护,就像某些古近纪祖猎虎类食肉动物,例如Eusmilus一样。简要评述了中国发现的先炭兽属的一些种,认为A. dawsoni可能是A. sinensis的同物异名。

关键词:

Abstract

The anthracotheriid (Mammalia, Cetartiodactyla) species Anthracokeryx thailandicus from the Upper Eocene of Thailand is redescribed in details and a revision of its phylogenetic position within the family is proposed. A combination of important dental differences has been observed that led to attribute the Thai form to a distinct genus, Geniokeryx gen. nov., which represents the third genus included into the Microbunodontinae. The new genus is characterized mainly by its unfused short and deep mandibular symphysis, massive lower and upper premolars, weakly selenodont upper molars that exhibit a protostyle and lack an ectometacristule. The peculiar morphology of its symphysis might have been a sexually dimorphic feature that provided the role of a lateral protection for the enlarged upper canine in males as seen in some Paleogene nimravid carnivorans like Eusmilus. A short review of some Anthracokeryx species from China suggests that A. dawsoni might be synonymous to A. sinensis.

Keywords:

PDF (1864KB)元数据多维度评价相关文章导出EndNote|Ris|Bibtex收藏本文

本文引用格式

DUCROCQ Stéphane. 泰国晚始新世Anthracokeryx thailandicus Ducrocq, 1999(石炭兽科,小丘齿兽亚科)的分类修订. 古脊椎动物学报[J], 2020, 58(4): 293-304 DOI:10.19615/j.cnki.1000-3118.200618

DUCROCQ Stéphane.

1 Introduction

Anthracokeryx is a Paleogene microbunodontine anthracothere that was first described in the upper Middle Eocene of the Pondaung Formation of Myanmar (A. tenuis and A. birmanicus, Pilgrim and Cotter, 1916). The genus is known only in the Eocene of Asia where several species have been recognized: A. birmanicus Pilgrim & Cotter, 1916 and A. tenuis Pilgrim & Cotter, 1916 in the late Middle Eocene of Myanmar; A. sinensis Zdansky, 1930 (for which much more complete material was described by Xu, 1962) and A. dawsoni Wang, 1985 in the late Middle Eocene of China; A. gungkangensis Qiu, 1977 and A. kwangsiensis Qiu, 1977 (these two species being probably conspecific; see Ducrocq, 1999) in the Middle/Late Eocene of China; A. naduongensis Ducrocq et al., 2015 in the early to middle Late Eocene of Vietnam and in the early Late Eocene of China (Averianov et al., 2019); and A. thailandicus Ducrocq, 1999 in the Late Eocene of Thailand. Concerning the species of Thailand its generic status has been questioned by Lihoreau et al. (2004), Lihoreau and Ducrocq (2007) and more recently by Averianov et al. (2019) because of its tooth and jaw morphology. In addition, recent phylogenies have suggested that the Thai species always appears more closely related to Microbunodon (the second genus included into the microbunodontines) than to other species of Anthracokeryx (Lihoreau et al., 2004, 2015; Lihoreau and Ducrocq, 2007; Soe et al., 2017) or even closer to bothriodontine anthracotheres (Averianov et al., 2019). Furthermore, a thorough description of the teeth of the holotype of A. thailandicus was not provided in the original publication (Ducrocq, 1999) that mostly focused on the skull anatomy. A careful reexamination of the upper and lower dentition of A. thailandicus is therefore needed that will help to discuss the systematic position of the Thai species and to clarify the evolutionary history of Microbunodontinae anthracotheres in Eurasia.Institutional abbreviations B, British Museum Natural History, London, UK; IVPP, Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China; LM, La Milloque fossil at PALEVOPRIM (Coll. M. Brunet), Université de Poitiers, France; ND, Na Duong Collections at the Institute of Marine Geology and Geophysics, Vietnam Academy of Science and Technology, Hanoi, Vietnam; Pkg, Paukkaung kyitchaung Collections at the Myanmar Ministry of Culture, Nay Pyi Taw, Myanmar; TF, Thai Fossil at the Department of Mineral Resources, Bangkok, Thailand.

Dental terminology The anthracothere dental terminology follows Boisserie et al. (2010).

2 Systematic paleontology

Type and only known species Anthracokeryx thailandicus (Ducrocq, 1999).

Etymology from the Greek “genien” (related to the chin) in reference to the strongly developed symphysis of the specimen. The suffix “keryx” refers to Anthracokeryx, a closely related anthracothere genus.

Diagnosis Middle sized anthracothere characterized by its unfused, short and ventrally protruding symphysis area, short upper and lower tooth rows, short diastema, wide lower premolars and molars, weak selenodonty, upper molars with a protostyle, moderately developed parastyle and mesostyle, and lacking an ectometacristule. Differs from most species of Anthracokeryx by its more massive upper premolars with P3 protocone more buccal and its P4 with a distinct lingual cingulum (A. dawsoni), postparaconule crista distally oriented (A. tenuis, A. birmanicus, A. sinensis), a mesiodistal crest connecting the protocone and the metaconule (A. tenuis, A. birmanicus, A. sinensis, A. naduongensis). Differs from Microbunodon by its unfused, short and deep symphysis, wider and more simple lower premolars, p4 with a smaller metaconid and endometacristid, longer and more massive lower molars, better developed hypoconulid lobe on m3, less selenodont upper premolars and molars with stronger parastyle, mesostyle and lingual cingulum, and weaker mesostyle on M3.

(Figs. 1-2A, B)

Holotype TF 2638, an almost complete cranium with left and right P3-M3 (Ducrocq, 1999).

Type locality and horizon Wai Lek coal mine, main lignite seam, Krabi Basin, southern Thailand. Late Eocene (Ducrocq, 1999).

Referred material TF 2639, a left mandibular fragment with p1-m2 (Wai Lek); TF 2656, isolated right m3 (Bang Pu Dam); TF 2831, fragmentary left palate with P4-M3 (Wai Lek); TF 2902, isolated left M3 (Wai Lek); TF 2832, isolated right M3 (Wai Lek); TF 2900, isolated left D4 (Wai Lek).

Diagnosis As for the genus.

3 Description

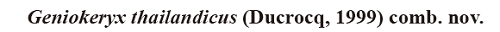

Geniokeryx thailandicus is known from a nearly complete cranium and lower jaw, a few isolated premolars and molars, and some carpal and tarsal elements (Ducrocq, 1999). However, the postcranial material attributed to different species of Anthracokeryx is at present too scarce to be used for diagnostic purposes.On the cranium TF 2638 (Fig. 1A), only P3 through M3 are known for G. thailandicus. P3 is separated from the sockets for the P2 by a short diastema (about 5.0 mm), it is triangular in occlusal view and the main cusp (paracone) displays two crests oriented mesially and distally respectively. A small and low protocone occupies the distolingual corner of the crown and is connected to the apex of the tooth by a very slight crest. A cingulum is present on all faces of P3 and is interrupted only in the middle of the buccal face. The apex of the tooth is also slanted backwardly. P4 typically consists of a paracone and a protocone separated by a longitudinal valley. The straight preparacrista ends at a parastyle that projects mesially. The mesial face of the crown is concave and the distal one is slightly convex. The paracone is taller than the protocone and is slanted backwardly. The preprotocrista connects with the mesial cingulum before reaching the parastyle, whereas the postprotocrista ends in the longitudinal valley against the lingual face of the paracone at a point distal to its apex. The postparacristule is mesiodistally oriented and ends in the central valley. A cingulum is present on all faces of the crown, it is stronger on the distal face and it is interrupted under the protocone. All of the upper molars (Figs. 1A, 2A?B) display the same structure with five cusps, a mesiobuccally projecting parastyle, a distinct metastyle that is more protruding on M3 and a small mesostyle. A distinct protostyle occurs on the mesial cingulum between the protocone and the paraconule. The buccal face of the metacone is flattened and slants lingually. The postparaconule crista is distally oriented. The metaconule displays only two crests: a premetacristule that ends in the center of the transverse valley as a slightly inflated knob in front of the postparacristule, and a postmetacristule that connects to the middle of the distal cingulum (there is no ectometacristule contrary to Lihoreau et al., 2004). The cingulum is absent only on the lingual face of the molars (measurements in Ducrocq, 1999).

Fig. 1

新窗口打开|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT

新窗口打开|下载原图ZIP|生成PPTFig. 1Photographs of Geniokeryx thailandicus from Krabi Basin, southern Thailand

A. skull TF 2638 in ventral view; B. left lower jaw TF 2639 in buccal view

The left lower jaw (TF 2639) is preserved from the anterior part of the symphysis to the posterior wall of m2 (Fig. 1B). A slight transverse constriction is present between the canine and p1. The transverse section of the unfused symphysis is oval, ventrally developed and convex. It is deeper than the horizontal ramus and extends from the canine to p2. Its deepest part is under p1. The horizontal ramus has a constant depth at least between p2 and the m3. The remaining socket for the lower canine is small and separated by a significant diastema (about 15 mm) from p1. This single-rooted and caniniform tooth is shorter and lower than the other premolars, convex buccally and flattened lingually, with its tip curved backwardly. The two-rooted p2, p3 and p4 are triangular and increase in complexity from front to back. The p2 has a simple triangular crown with a mesial and distal crest, no cingulid and only a very tiny and narrow shelf of enamel occurs mesially and distolingually. Its buccal face is convex and its lingual side is flat. The p2 is separated by a short diastema (about 8.0 mm) from the p1. The structure of p3 is very similar to that of p2 with a narrow buccal cingulid that interrupts in the center of the crown. The distal crest is stronger and slightly curves distolingually where it ends in an incipient talonid. This tooth is taller than other premolars. The p4 displays a third distolingual crest that extends from the tip of the crown to the distolingual cingulid. The mesial and buccal cingulid are better developed and the crown is wider in its distal part. The talonid of m1 is wider than its trigonid, as is generally the case in anthracotheres, and the trigonid cusps are slightly taller than the talonid ones. The preprotocristid and premetacristid connect at the bottom of the mesial face of the metaconid, and the postprotocristid and postmetacristid close the trigonid distally. A very short endometacristid projects mesiobuccally from the tip of the metaconid to the bottom of the longitudinal valley of the trigonid. A moderately developed postectometacristid extends from the tip of the cusp down to the lingual end of the transverse valley where it joins an ectoentocristid that extends from the tip of the entoconid. Both mesial cusps are transversely in line, the mesial end of the trigonid is lingually oblique and only a very slight and low mesial cingulid is present. The entoconid is slightly more mesial than the hypoconid. A low prehypocristid extends to the middle of the distal wall of the trigonid and although the tooth is worn it is possible to distinguish a faint preentocristid connecting the entoconid and the prehypocristid. The distal part of the talonid is not very well preserved but a very slight posthypocristid extends distolingually to the base of the entoconid above a narrow distal cingulid that bears a very small distostylid. A short and narrow buccal cingulid occurs under the buccal end of the transverse valley. The m2 is very similar to the m1 except for its somewhat less elongated crown more rounded on its mesial face, and its better developed distostylid. The m3 (TF 2656) is morphologically similar to m2 (Fig. 2B). However, its mesial face is more quadratic, its trigonid is slightly wider than its talonid and its buccal cingulid is more developed. The posthypocristid distobuccally extends to the hypoconulid to form a loop that lines the lingual side of the cusp and ends in the valley that separates the hypoconulid and the entoconid. A very short buccal cingulid is present between the hypoconid and the hypoconulid (measurements in Ducrocq, 1999).

Fig. 2

新窗口打开|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT

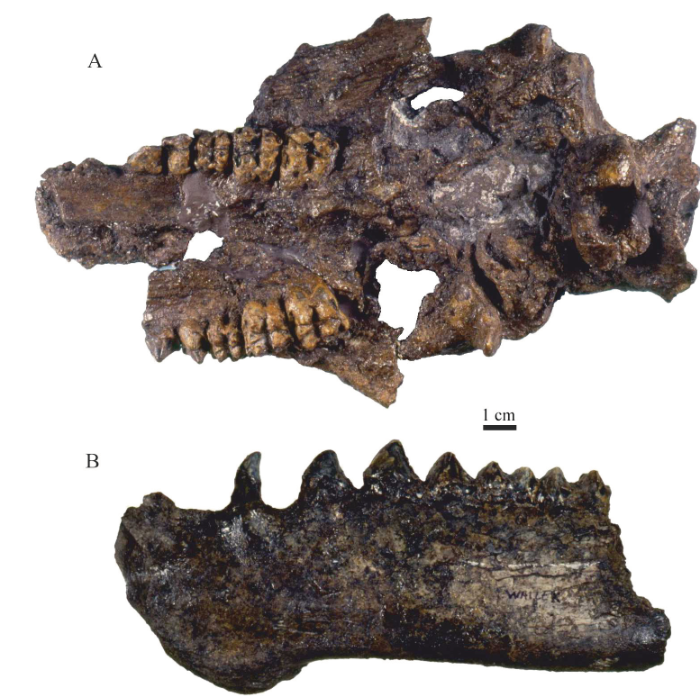

新窗口打开|下载原图ZIP|生成PPTFig. 2Interpretative drawings of upper and lower molars (m3) of the microbunodontine taxa

A-B. Geniokeryx thailandicus: A. left upper molar TF 2638, B. right m3 TF 2656; C-D. Anthracokeryx birmanicus: C. left upper molar Pkg-169, D. right m3 B-605; E-F. A. tenuis: E. left upper molar B-756,F. right m3 B-755; G-H. A. gungkangensis: G. right upper molar (inverted) IVPP V 4950, H. left m3 (inverted) V 4950; I-J. A. naduongensis: I. left upper molar (inverted) ND 2012-02-15-1, J. left m1 (inverted) ND 2012-02-16-2; K-L. A. sinensis: K. left upper molar IVPP V 63321, L. left m2 (inverted) V 63320;

M. A. kwangsiensis, left upper molar IVPP V 4951; N. A. dawsoni, left upper molar V 7915;

O-P. Microbunodon minimum: O. left upper molar LM1967MA300, P. right m3 LM1970MA57. Not to scale

4 Comparisons

The upper and lower teeth of the Thai anthracothere display several morphological differences with those of species of Anthracokeryx. The Pondaung A. tenuis and A. birmanicus are smaller but have a longer upper tooth row with longer diastema, their molars are more selenodont, they have better developed parastyles and postectometacrista, less distally protruding metastyle, a slightly smaller paraconule, no protostyle, a distinct ectometacristule (mesiolingual crest of the metaconule), a short and narrow mesiodistal crest that connects the metaconule and the protocone (Fig. 2C, E), and mesiodistally shorter P4. The p3 and p4 of Genyokeryx are less transversely compressed and their crests are relatively less marked, especially when compared with those of the Pondaung species. The latters also exhibit more selenodont lower molars with more transverse preentocristids, slightly taller crests (A. birmanicus), and m3 with weaker buccal cingulids and more buccally bent hypoconulid lobe (Fig. 2D, F). Anthracokeryx gungkangensis and A. kwangsiensis display more selenodont upper molars with a stronger parastyle, a less developed metastylar region, a strong lingual cingulum and a distinct ectometacristule (Fig. 2G, M). The P4 of A. kwangsiensis is also more selenodont with a stronger mesial cingulum. The lower molars of A. gungkangensis are very similar in size and morphology with those of the Thai species, the only noticeable difference being better developed mesial and distal cingulids on m3 of the Chinese species (Fig. 2H). The Vietnamese A. naduongensis is much smaller, it has upper molars with less buccally protruding metaconule, no protostyle, better developed parastyle, mesostyle and lingual cingulum, and a small mesiodistal crest connecting the protocone and the metaconule. It also exhibits slightly more selenodont lower molars with a trigonid almost as wide as the talonid, and lower premolars more laterally compressed (Fig. 2I, J). Anthracokeryx sinensis is slightly smaller and its upper teeth can be distinguished by their stronger selenodonty, their more rectangular outline, with a weaker and more mesially positioned paraconule, a postparaconule crista distobuccally oriented and connecting to the distolingual wall of the paracone (postparaconule crista distally oriented and extending to the central valley in the Thai anthracothere), a very slight mesiodistal crest that connects the distal wall of the protocone and the mesial wall of the metaconule, a distinct ectometacristule, a better developed parastyle and no protostyle (Xu, 1962). Its p3 and a p4 have length-width proportions more similar to those of the Thai species but they are slightly more laterally compressed and of of similar height. The Chinese species also exhibits a talonid of p4 more developed distolingually and p3 comparatively taller. This species also has somewhat more slender lower molars with deeper buccal sinusids, and a narrower hypoconulid lobe on m3 (Fig. 2K, L). Anthracokeryx dawsoni is slightly smaller, it also has less massive premolars; its P3 exhibits a protocone in a more lingual position, and stronger buccal and lingual cingula; its P4 is more slender distally and lacks a lingual cingulum; its molars have stronger cingula and better developed styles but no protostyle, and their metaconule display an ectometacristule (Fig. 2N). Consequently, Geniokeryx can be clearly distinguished from Anthracokeryx by the combination of its much more massive horizontal ramus with a short and deep mandibular symphysis, its shorter diastema, more massive lower and upper premolars, less selenodont lower and upper molars with a protostyle, weaker parastyle, and lacking an ectometacristule.The Microbunodontinae also include the genus Microbunodon (Late Eocene to Late Miocene of Eurasia) that greatly differs from the Thai form by its fused, much shallower, longer and not ventrally salient symphysis, more anteriorly protruding lower jaw, its more narrow lower premolars, weaker and lower p1, p4 with better developed metaconid and endometacristid, its less elongated lower molars and its m3 with a less developed hypoconulid lobe, its P3 with stronger cingula, its more selenodont P4 with a stronger parastyle, its more selenodont upper molars with stronger parastyle, mesostyle and lingual cingulum, but weaker metastyle on M3 (Fig. 2O, P).

Although the Thai anthracothere displays a dental morphology that clearly contrasts with that of Anthracokeryx and Microbunodon, its attribution to the subfamily Microbunodontinae is supported by the combination of lateral constriction of the lower jaw behind the lower canine, and the marked diastema between the lower canine and the p1. This consequently warrants the Thai anthracothere to be attributed to a distinct genus, as previously proposed by several authors (Lihoreau et al., 2004; Lihoreau and Ducrocq, 2007; Averianov et al., 2019).

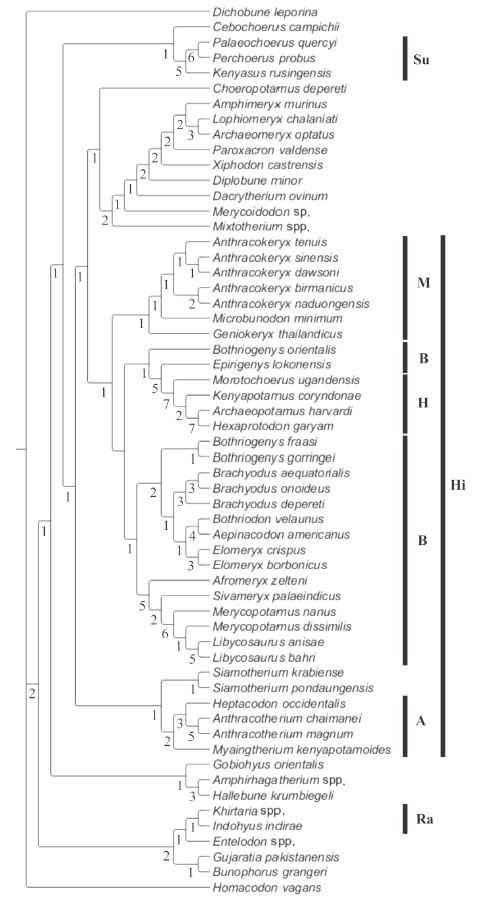

In order to illustrate and confirm the position of Geniokeryx within the micro-bunodontines, all known species of Anthracokeryx have been included and coded into the most recent phylogeny published for hippopotamoids (anthracotheres + Hippopotamidae). The phylogenetic analysis performed here used the matrix of characters published by Lihoreau et al. (2015), in which the dental character scores for A. birmanicus, A. sinensis, A. dawsoni, A. naduongensis and Geniokeryx thailandicus have been included and/or updated. The final data matrix comprises a total of 58 cetartiodactyl taxa and 164 dental and cranial characters (see Appendix). Following Lihoreau et al. (2015), the homacodontid Homacodon vagans and the diacodexeids Gujaratia pakistanensis and Bunophorus grangeri were designated outgroup taxa. A heuristic search (1,000 replications with randomized addition of the taxa) was performed using PAUP 4b10 (Swofford, 2002) with all characters unweighted and all multistate characters unordered.

One most parsimonious tree of 1025 steps was obtained (consistency index [CI] = 0.21; retention index [RI] = 0.60). The topology of the tree found (Fig. 3) is rather similar to those published by Lihoreau et al. (2015) and Soe et al. (2017) in that the three anthracotheriid subfamilies (Anthracotheriinae, Microbunodontinae, Bothriodontinae) are preserved. In this analysis, Geniokeryx is sister taxon to the clade [Microbunodon + Anthracokeryx] and it appears as a distinct genus within the Microbunodontinae. The grouping of species of Anthracokeryx is supported by 12 synapomorphies unknown in Geniokeryx: connection of preentocristid and endohypocristid (52?0), the presence of a postentocristid on lower molars (55?1), the presence of an endohypocristid on lower molars (61?1), the presence of a diastema between P1 and P2 (78?1), a simple paracone on P4 that lacks fossa (86?0), a P4 preprotocrista that joins the base of the paracone (90?1), moderately developed buccal ribs on upper molars (102?0), the presence of a postectoprotocrista on upper molars (103?1), a premetacristule on upper molars divided into mesial arms (106?1), an upper molar parastyle larger than the mesostyle (122?2), a reduced to absent metastyle on upper molars (128?0), and the presence of a diastema between p2 and p3 (144?0). Alternatively, characters that define Geniokeryx are the absence of a lingual cingulum (101?2) and a markedly reduced mesostyle on upper molars (127?0), and a deep and ventrally protruding mandibular symphysis with a maximum depth in its middle part (139?0).

Fig. 3

新窗口打开|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT

新窗口打开|下载原图ZIP|生成PPTFig. 3Tree obtained from the cladistics analysis (1025 steps, CI = 0.21, RI = 0.60)

Values below the branches are Bremer support indicesAbbreviations: A. Anthracotheriinae; B. Bothriodontinae; H. Hippopotamidae; Hi. Hippopotamoidea;

M. Microbunodontidae; Ra. Raoellidae; Su. Suoidea

5 Discussion

Apart from its less selenodont teeth, more massive premolars and lack of an ecto-metacristule on upper molars, the most striking feature that distinguishes Geniokeryx thailandicus from all microbunodontine species is the shape of its lower jaw and symphysis. Indeed, in all specimens of Anthracokeryx where these parts are more or less preserved (species from Pondaung and Vietnam, A. sinensis from China), the horizontal ramus is slender and curved ventrally, it is deeper under m2 and markedly shallower mesially and distally to that tooth. In addition, their mandibular symphysis is always shallow, mesiodistally elongated (it reaches the level under the distal part of p2) and does not protrude ventrally. In G. thailandicus, the horizontal ramus is deep, it has a constant depth from p2 to m2 and tends to grow deeper distally to m2, and the symphysis is much deeper, oval shaped and ventrally very salient. In addition, its short anterior end is not forwardly projecting but is slanting at an angle of about 45°, suggesting that the area for the incisors might have been reduced in Geniokeryx. Overall, the lower jaw of the Thai anthracothere was proportionally more massive and shorter than that of all species of Anthracokeryx. Similarly, the fused mandibular symphysis in Microbunodon species is long and not ventrally protruding as in the Thai anthracothere, although it exhibits a small ventrally prominent genial crest (Lihoreau et al., 2004). The horizontal ramus is deeper under m2-m3 in all species of Microbunodon. No other anthracothere displays a symphysis morphology similar to that of Geniokeryx. However, the shape of the symphysis in the Thai anthracothere might have had a function similar to that of this part of the jaw in some nimravid genera like Eusmilus where the elongated upper canines lie against the mental flange; this would have provided extra lateral protection to the large upper canines when the mouth was closed (Van Valkenburgh, 2007). In addition, the lateral constriction of the lower jaw behind the lower canine probably allowed room for the tip of the upper canine. The mental flange in Geniokeryx might have been a feature typical of males where it was more developed than in females. Indeed, one diagnostic feature of microbunodontines is the presence of enlarged upper canines in males (Lihoreau and Ducrocq, 2007), and although this tooth is unknown in the Thai anthracothere, it is very likely that such a developed upper canine was present in it and that it was related to the anterior part of the jaw peculiar morphology found in microbunodontines.Averianov et al. (2019) stated that the Thai anthracothere and A. gungkangensis (and thus A. kwangsiensis according to Ducrocq, 1999) might be conspecific on the basis of their similar size. The thorough description and comparisons of these taxa show that although both species share lower teeth close in size and structure, the Chinese species differs from the Thai one by several important features including stronger selenodonty, styles and cingula development, and presence of an ectometacristule on upper molars. The combination of these dental characters that are exhibited by A. gungkangensis supports its attribution to the genus Anthracokeryx and further demonstrates that it is not congeneric with the Thai form.

Averianov et al. (2019) also suggested that A. sinensis and A. dawsoni might correspond to the same species. Indeed, the upper molars have similar dimensions in both taxa and they exhibit very close morphology and structure. Xu (1962) was the first to describe the upper dentition of A. sinensis, and the features listed by Wang (1985) that distinguish the upper teeth of A. dawsoni from those of A. sinensis (low and obtuse cusps, continuous buccal cingulum at the base of the paracone, preparacrista that joins the parastyle medially) can depend on the wear of the teeth (height and sharpness of cusps) and on individual variation (cingulum, extension of the preparacrista). It is therefore likely that A. dawsoni and A. sinensis represent the same species. In addition, the phylogenetic tree presented in Fig. 3 shows A. dawsoni and A. sinensis as sister taxa, which supports their very close relationships, or even that they represent the same taxon. In that case, A. sinensis would have the priority over A. dawsoni following the principle of priority, and would represent one of the few species of Anthracokeryx known by very complete dental material.

6 Conclusions

The thorough reexamination and comparisons of the dental structure and morphology of Anthracokeryx thailandicus from the late Eocene of Thailand led to confirm that this anthracothere belongs to the Microbunodontinae mainly because of the morphology of the anterior part of its lower jaw. However, it can be demonstrated that its molar and premolar structure justify to refer it to a distinct new genus, Geniokeryx, which represents the third genus included into the subfamily Microbunodontinae. The peculiar morphology of its deep mandibular symphysis might correspond to a sexually dimorphic character that probably had a function similar to that of that part of the jaw in sabertooth cats (lateral protection of the upper enlarged canine when the mouth was closed). Other hypotheses suggested by Averianov et al. (2019) concerning the synonymy of the Thai species with A. gungkangensis and of A. dawsoni with A. sinensis have been tested, and precise comparisons and phylogenetic results showed that Geniokeryx is clearly distinct from all of the known microbunodontine species, and that A. dawsoni likely represents the same species as A. sinensis.Acknowledgements

Many thanks to S. Riffaut for her help with photographic assistance. Thanks to Wang Yuan-Qing and an anonymous reviewer whose comments significantly improved the earlier version of the manuscript. This work has been supported by the ANR-09-BLAN-0238 Program, the CNRS UMR 7262 (PALEVOPRIM), and the University of Poitiers.Appendix can be found on the website of Vertebrate PalAsiatica (

参考文献 原文顺序

文献年度倒序

文中引用次数倒序

被引期刊影响因子

DOIURLPMID [本文引用: 6]

Here we report the first record of one of the most common and widespread Palaeogene selachians, the sand tiger shark Brachycarcharias, from the Ypresian Bolca Konservat-Lagerstatte. The combination of dental character of the 15 isolated teeth collected from the Pesciara and Monte Postale sites (e.g. anterior teeth up to 25 mm with fairly low triangular cusp decreasing regularly in width; one to two pairs of well-developed lateral cusplets; root with broadly separated lobes; upper teeth with a cusp bent distally) supports their assignment to the odontaspidid Brachycarcharias lerichei (Casier, 1946), a species widely spread across the North Hemisphere during the early Palaeogene. The unambiguous first report of this lamniform shark in the Eocene Bolca Konservat-Lagerstatte improves our knowledge concerning the diversity and palaeobiology of the cartilaginous fishes of this palaeontological site, and provides new insights about the biotic turnovers that involved the high trophic levels of the marine settings after the end-Cretaceous extinction.

[本文引用: 1]

[本文引用: 10]

[本文引用: 4]

DOIURLPMID [本文引用: 5]

Zaldivar-Riveron, A., Areekul, B., Shaw, M. R. & Quicke, D. L. J. (2004). Comparative morphology of the venom apparatus in the braconid wasp subfamily Rogadinae (Insecta, Hymenoptera, Braconidae) and related taxa. -Zoologica Scripta, 33, 223-237. The morphology of the venom apparatus intima in representatives of 38 genera of the problematic braconid wasp subfamily Rogadinae and other cyclostome braconids was investigated and a preliminary phylogenetic analysis for the group was performed with the information obtained. Despite the limited number of characters, the data suggest several relationships at various taxonomic levels. The venom apparatus in the Clinocentrini and the Stiropiini is relatively unmodified and similar to that found in other genera previously placed within a broader concept of the Rogadinae (e.g. genera of Lysitermini, Pentatermini, Tetratermini, Hormiini) and also to that of the Betylobraconinae. The presence of a cone of filaments located inside the secondary venom duct near to its insertion on the venom reservoir/primary venom duct is proposed as a synapomorphy for the tribe Rogadini to the exclusion of Stiropiini, Clinocentrini and Yeliconini. Other features of the secondary venom duct and its insertion on the venom reservoir/primary venom duct support a number of relationships between the genera of the Rogadini and also within the large genus Aleiodes. A clade containing 15 Rogadini genera (Bathoteca, Bathotecoides, Bulborogas, Canalirogas, Colastomion, Conspinaria, Cystomastacoides, Macrostomion, Megarhogas, Myocron, Pholichora, Rectivena, Rogas, Spinaria and Triraphis) is supported by the presence of a thickened and short secondary venom duct, whereas the different members of Aleiodes (excluding members of the subgenus Heterogamus) and Cordylorhogas are distinguished by having a recessed secondary venom duct with well-defined and numerous internal filaments. New World Rogas species exhibit a unique venom apparatus and may not be closely related to the Old World ones. Features of the venom apparatus of the enigmatic genus Telengaia and the exothecine genera Shawiana and Colastes suggest that the Telengainae and Exothecinae are both closely related to the Braconinae, Gnamptodontinae, and possibly to the Opiinae and Alysiinae. An unsculptured venom reservoir was found in one specimen of the type species of Avga, A. choaspes, which is consistent with it occupying either a very basal position within the cyclostome braconids or belonging to a recently recognized 'Gondwanan' clade that also includes the Aphidiinae.

URLPMID [本文引用: 4]

DOIURLPMID

A data set of complete mitochondrial cytochrome b and 12S rDNA sequences is presented here for 17 representatives of Artiodactyla and Cetacea, together with potential outgroups (two Perissodactyla, two Carnivora, two Tethytheria, four Rodentia, and two Marsupialia). We include seven sequences not previously published from Hippopotamidae (Ancodonta) and Camelidae (Tylopoda), yielding a total of nearly 2.1 kb for both genes combined. Distance and parsimony analyses of each gene indicate that 11 clades are well supported, including the artiodactyl taxa Pecora, Ruminantia (with low 12S rRNA support), Tylopoda, Suina, and Ancodonta, as well as Cetacea, Perissodactyla, Carnivora, Tethytheria, Muridae, and Caviomorpha. Neither the cytochrome b nor the 12S rDNA genes resolve the relationships between these major clades. The combined analysis of the two genes suggests a monophyletic Cetacea +Artiodactyla clade (defined as

[本文引用: 1]

[本文引用: 2]

[本文引用: 2]

[本文引用: 1]

DOIURLPMID [本文引用: 1]

The fossil record of the order Carnivora extends back at least 60 million years and documents a remarkable history of adaptive radiation characterized by the repeated, independent evolution of similar feeding morphologies in distinct clades. Within the order, convergence is apparent in the iterative appearance of a variety of ecomorphs, including cat-like, hyena-like, and wolf-like hypercarnivores, as well as a variety of less carnivorous forms, such as foxes, raccoons, and ursids. The iteration of similar forms has multiple causes. First, there are a limited number of ways to ecologically partition the carnivore niche, and second, the material properties of animal tissues (muscle, skin, bone) have not changed over the Cenozoic. Consequently, similar craniodental adaptations for feeding on different proportions of animal versus plant tissues evolve repeatedly. The extent of convergence in craniodental form can be striking, affecting skull proportions and overall shape, as well as dental morphology. The tendency to evolve highly convergent ecomorphs is most apparent among feeding extremes, such as sabertooths and bone-crackers where performance requirements tend to be more acute. A survey of the fossil record indicates that large hypercarnivores evolve frequently, often in response to ecological opportunity afforded by the decline or extinction of previously dominant hypercarnivorous taxa. While the evolution of large size and carnivory may be favored at the individual level, it can lead to a macroevolutionary ratchet, wherein dietary specialization and reduced population densities result in a greater vulnerability to extinction. As a result of these opposing forces, the fossil record of Carnivora is dominated by successive clades of hypercarnivores that diversify and decline, only to be replaced by new hypercarnivorous clades. This has produced a marvelous set of natural experiments in the evolution of similar ecomorphs, each of which start from phylogenetically and morphologically unique positions.

[本文引用: 2]

[本文引用: 3]