HTML

--> --> -->PMIP has had a long history of collaboration with the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP) since its second phase (Braconnot et al., 2007, 2011). At present, PMIP is proceeding to the fourth phase (PMIP4), and collaboration with the sixth phase of CMIP (CMIP6) is enhanced (Kageyama et al., 2018). Simulations of five key epochs have been designed for the scientific objectives in CMIP6, including the millennium prior to the industrial epoch (CMIP6 name past1000, 850–1849 CE), the mid-Holocene (midHolocene, 6 ka BP), the Last Glacial Maximum (lgm, 21 ka BP), the Last Interglacial (lig127k, 127 ka BP), and the mid-Pliocene Warm Period (midPlioceneEoi400, 3.2 Ma BP). These epochs are ranked as Tier 1 priority simulations in CMIP6. The choice of these key climatic periods is based on previous PMIP experience and is justified by the need to address the key CMIP6 question “How does the Earth system respond to forcing?” (Eyring et al., 2016). These climatic periods are well documented by paleo-records that favor the model validations. PMIP4 also uses various sensitivity simulations to address the roles of different forcings and the uncertainties in the boundary and initial conditions (e.g., vegetation and ice sheets) in each paleoclimate period, which are ranked as other priorities (Tier 2 or 3) (Jungclaus et al., 2017; Kageyama et al., 2017; Otto-Bliesner et al., 2017). By providing paleoclimate simulations and the mechanism in changes of climate, PMIP4 will also contribute to other CMIP6 projects and the projection of future climate change (Zheng et al., 2019).

The coupled climate model of the Chinese Academy of Sciences Flexible Global Ocean–Atmosphere–Land System model (CAS-FGOALS) was developed at the State Key Laboratory of Numerical Modeling for Atmospheric Sciences and Geophysical Fluid Dynamics (LASG) of the Institute of Atmospheric Physics (IAP), Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS). CAS-FGOALS has been part of PMIP since PMIP2 and the simulations of the mid-Holocene and Last Glacial Maximum are performed by FGOALS-1.0g (Zheng et al., 2008; Yu et al., 2010). In PMIP3, three versions of FGOALS [FGOALS-g2 (Li et al., 2013), FGOALS-s2 (Bao et al., 2013), and FGOALS-gl (Man and Zhou, 2011)] provide more simulations than the key epochs in PMIP2, including the last millennium (Man and Zhou, 2011), the mid-Holocene, the Last Glacial Maximum (Zheng and Yu, 2013), and the mid-Pliocene Warm Period (Zheng et al., 2013).

Two new versions of CAS-FGOALS (hereinafter referred to as FGOALS-f3-L and FGOALS-g3) have been developed in recent years and used in the CMIP6 and PMIP4 simulations. CAS-FGOALS will contribute to PMIP4 by providing the five key paleoclimate simulations designed for CMIP6–PMIP4. The simulations of the two interglacial simulations of the mid-Holocene and Last Interglacial by FGOALS-f3-L and FGOALS-g3 were completed in September 2019. The simulation data were then post-processed by the Climate Model Output Rewriter (CMOR) and submitted by mid-November to the Earth System Grid Federation (ESGF) data server (

This paper is organized as follows. Section 2 gives basic information about the CAS-FGOALS models and experimental protocols for the two interglacial epochs. Section 3 presents preliminary validations of the datasets, and section 4 describes the datasets and gives information on their usage.

2.1. CAS-FGOALS models

The most recent generation of CAS-FGOALS is version 3 (CAS-FGOALS3). Two versions are used for the PMIP4 simulations: FGOALS-f3-L (He et al., 2019) and FGOALS-g3 (Li et al., 2020). Both these CAS-FGOALS models are based on the coupling framework of CPL7 (Craig, 2014), which connects the four components of atmosphere, ocean, land, and sea ice. The oceanic component, LICOM3 [LASG/IAP Climate Ocean Model, version 3 (Lin et al., 2020)] is identical in both versions. LICOM3 adopts a tripolar grid with a horizontal resolution of 360 by 218 grid points and 30 levels in the vertical direction.Different configurations of the atmospheric, land surface, and sea-ice models are used in the two versions. The Finite-volume Atmospheric Model (FAMIL) (Li et al., 2019), version 2.2, is coupled as the atmospheric component in FGOALS-f3-L, which has a horizontal resolution of C96 (about 1° × 1°) and 32 levels in the vertical direction with the model top at 2.16 hPa. The Community Land Model, version 4.0 (CLM4) (Oleson et al., 2010), and the Community Ice CodE version 4 (CICE4) (Hunke and Lipscomb, 2010), are coupled as the land and sea-ice components, respectively. FGOALS-g3 is a grid-point version that contains a grid-point atmospheric model named GAMIL3 (Li et al., in prep.) with a horizontal resolution of 2° and 26 vertical layers up to 2.194 hPa. The land surface model used in FGOALS-g3 is a revised version of the Community Land Model, version 4.5 (CLM4.5), and has the same horizontal resolution as GAMIL3. The improved Community Ice CodE, version 4 (CICE4) (Liu, 2010), is coupled with the same resolution as the ocean model.

2

2.2. Protocols for the two interglacial experiments

The two most recent interglacial epochs of the mid-Holocene (midHolocene; 6 ka BP) and the Last Interglacial (lig127k; 127 ka BP) are included in PMIP4, which is designed to focus on the impact of changes in the Earth’s orbital parameters on the global climate. Table 1 summarizes the external forcings and boundary conditions. More details about the experiment protocols, including the sources and derivation, can be found in Otto-Bliesner et al. (2017).| Experiment | 0 ka (piControl) | 6 ka (midHolocene) | 127 ka (lig127k) | |

| Orbital parameter | Eccentricity | 0.016764 | 0.018682 | 0.039378 |

| Obliquity (°) | 23.459 | 24.105 | 24.04 | |

| Perihelion–180 | 100.33 | 0.87 | 275.41 | |

| Vernal equinox | 21 March | 21 March | 21 March | |

| Greenhouse gas concentrations | CO2 (ppm) | 284.3 | 264.4 | 275 |

| CH4 (ppb) | 810.0 | 597 | 685 | |

| N2O (ppb) | 272.9 | 262 | 255 | |

| CFCs | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Solar constant (W m?2) | 1360.747 | 1360.747 | 1360.747 | |

| Paleogeography | Modern | piControl | piControl | |

| Ice sheets | Modern | piControl | piControl | |

| Vegetation | piControl | piControl | piControl | |

| Aerosols | piControl | piControl | piControl | |

Table1. External forcings and boundary conditions for the two interglacial epochs.

In both FGOALS-f3-L and FGOALS-g3, the orbital parameters (eccentricity, obliquity, and longitude of perihelion) are calculated following the method of Berger and Loutre (1991). The orbital year used for piControl (0 ka) is 1850 CE (Eyring et al., 2016). The eccentricity at 6 ka is 0.018682, which is similar to that at 0 ka. The obliquity is slightly larger (24.105) at 6 ka, and perihelion occurs close to the boreal autumn equinox. At 127 ka, the eccentricity (0.039378) and obliquity (24.04) are larger than those at 0 ka, and perihelion occurs close to the boreal solstice. To avoid the fact that the length of the seasons varies with precession and eccentricity (Joussaume and Braconnot, 1997), the vernal equinox has been set to noon on 21 March in both the simulations in piControl. The solar constant in the 6 and 127 ka simulations is the same as at 0 ka, which is fixed at 1360.747 W m?2 (Eyring et al., 2016). This value is lower than previously used in PMIP3 (1365 W m?2) and will result in a global reduction in insolation.

The concentrations of greenhouse gases used in CAS-FGOALS are almost the same as specified by Otto-Bliesner et al. (2017), although they were slightly different for methane (CH4) and nitrous oxide (N2O) at 0 ka due to the model calculations. Realistic concentrations of greenhouse gases (264.4 ppm CO2, 597 ppb CH4 and 262 ppb N2O) are used for the 6 ka simulation. The concentrations of greenhouse gases at 127 ka were 275 ppm CO2, 685 ppb CH4 and 255 ppb N2O. The concentrations of chlorofluorocarbons are prescribed as 0 at 0 ka and in the two interglacial simulations. The boundary conditions of geography, ice sheets, vegetation and aerosols in the interglacial simulations are all prescribed as in piControl (Table 1) following the guidelines in Otto-Bliesner et al. (2017).

2

2.3. Interglacial simulations by CAS-FGOALS

Following the experiment protocols, the interglacial simulations of FGOALS-f3-L and FGOALS-g3 were launched by taking a random year from their corresponding piControl simulation as the initial condition. FGOALS-g3 provided three realizations starting from different initial conditions for the mid-Holocene, whereas the other simulations had only one realization (Table 2). All the simulations were integrated for long enough to reach an equilibrium state and the last 500 years were processed by CMOR. Monthly data were available for 500 years and daily outputs were available for the last 50 years.| Model | Experiment_id | Variant_label | Data length | |

| Monthly (500 yr) | Daily (50 yr) | |||

| FGOALS-f3-L | midHolocene | r1i1p1f1 | 0720–1219 | 1170–1219 |

| lig127k | r1i1p1f1 | 0700–1199 | 1150–1199 | |

| FGOALS-g3 | midHolocene | r1i1p1f1 | 0627–1126 | 1077–1126 |

| r2i1p1f1 | 0620–1119 | 1070–1119 | ||

| r3i1p1f1 | 0350–0849 | 0800–0849 | ||

| lig127k | r1i1p1f1 | 0750–1249 | 1200–1249 | |

Table2. Information on the interglacial simulations by CAS-FGOALS3.

We choose the realization “r1i1p1f1” for each epoch by the two versions of CAS-FGOALS for the preliminary validation of the large-scale features of temperature and precipitation, as well as the interannual variabilities in the ocean. The “paleo-calendar effect” that accounts for the impact of changes in the length of months or seasons over time, related to changes in the eccentricity of the Earth’s orbit and precession, are taken into account following the methodology of Bartlein and Shafer (2019). Quantitative reconstructions are also used for the model–data comparisons. For the mid-Holocene, the pollen-based continental climate reconstructions of Bartlein et al. (2011) are used to validate the mean annual temperature and precipitation over land. The surface climate compilation of the 127 ka time slice (Capron et al., 2017) is used to evaluate the high-latitude amplification of warming during the Last Interglacial in the PMIP4 simulations.

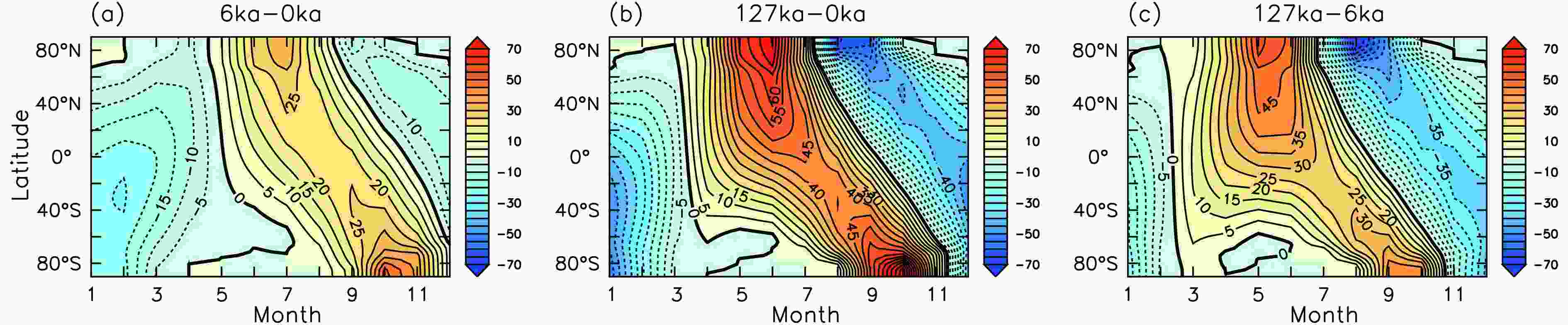

The changes in orbital parameters result in different seasonal and latitudinal distributions of solar radiation at the top of the atmosphere compared with piControl (Figs. 1a and b). The changes in insolation anomalies yielded by the two versions of CAS-FGOALS3 are almost exactly the same as those shown in the experimental design for 6 and 127 ka (Otto-Bliesner et al., 2017). Large positive anomalies occur in the high latitudes of the Northern Hemisphere during the boreal summer for both interglacial simulations. At 6 ka, the anomalies reach a peak in July, with values of about 25 W m?2 around 40°N, whereas at 127 ka the insolation anomalies peak in June, with larger values of about 55–60 W m?2. The differences between the two interglacials imply larger changes in the seasonal cycle at 127 ka than at 6 ka (Fig. 1c).

Figure1. Latitude–month insolation anomalies calculated using the modern calendar with the vernal equinox on 21 March at noon: (a) 6 ka–0 ka; (b) 127 ka–0 ka; and (c) 127 ka–6 ka (units: W m?2).

Figure1. Latitude–month insolation anomalies calculated using the modern calendar with the vernal equinox on 21 March at noon: (a) 6 ka–0 ka; (b) 127 ka–0 ka; and (c) 127 ka–6 ka (units: W m?2).3.1. Response of surface temperature

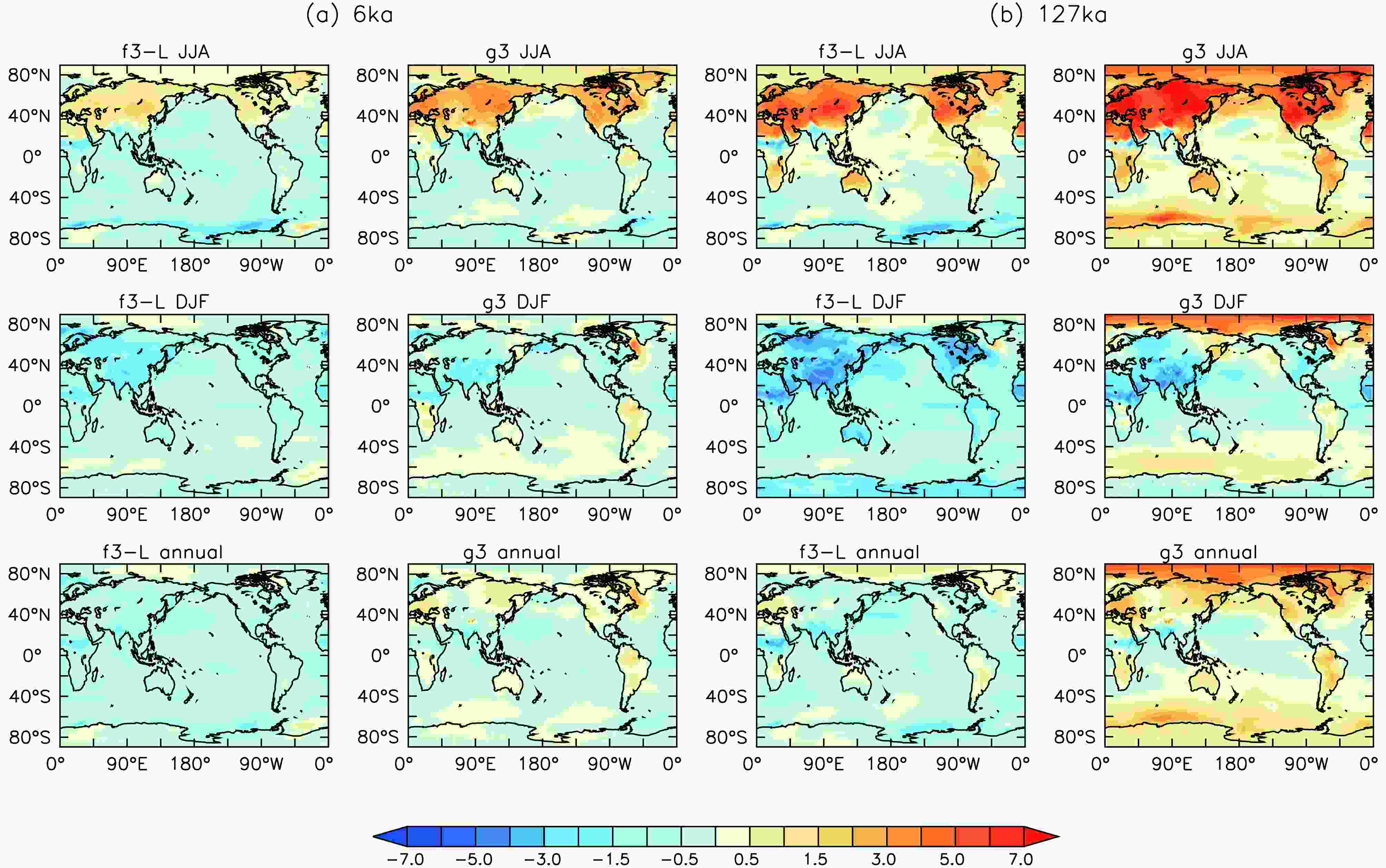

Figure 2 shows the changes in surface temperature in the two interglacial epochs relative to 0 ka. As expected from the changes in solar insolation, both the CAS-FGOALS models simulate significant warming in summer over the continents in the Northern Hemisphere (Fig. 2a), but a slight cooling over the oceans. The warming is about 2°C in mid-to-high latitudes in FGOALS-g3, larger than the warming in FGOALS-f3-L (~1°C). Cooling related to enhanced summer monsoonal precipitation can be observed in North Africa and South Asia (Fig. 3a). Reduced insolation in the boreal winter results in surface cooling in the Northern Hemisphere, where ocean cooling is much weaker than the cooling of the continents as a result of the ocean’s large heat capacity. In contrast with FGOALS-f3-L, FGOALS-g3 shows a larger response to the increased insolation in the Southern Hemisphere, with warming over South Africa, Australia, South America, and the Southern Ocean. Warming is also seen in the North Atlantic during boreal winter, implying changes in the northward transport of heat in the ocean. Figure2. Changes in surface temperature at (a) 6 ka and (b) 127 ka for FGOALS-f3-L and FGOALS-g3 relative to 0 ka. The changes in surface temperature averaged for June–July–August (JJA) (top), December–January–February (DJF) (middle), and the annual mean (bottom), are shown (units: °C).

Figure2. Changes in surface temperature at (a) 6 ka and (b) 127 ka for FGOALS-f3-L and FGOALS-g3 relative to 0 ka. The changes in surface temperature averaged for June–July–August (JJA) (top), December–January–February (DJF) (middle), and the annual mean (bottom), are shown (units: °C). Figure3. Changes in precipitation at (a) 6 ka and (b) 127 ka for FGOALS-f3-L and FGOALS-g3 relative to 0 ka. The changes in precipitation averaged for June–July–August (JJA) (top), December–January–February (DJF) (middle), and the annual mean (bottom), are shown (units: mm d?1).

Figure3. Changes in precipitation at (a) 6 ka and (b) 127 ka for FGOALS-f3-L and FGOALS-g3 relative to 0 ka. The changes in precipitation averaged for June–July–August (JJA) (top), December–January–February (DJF) (middle), and the annual mean (bottom), are shown (units: mm d?1).The changes in surface temperature imply that the model is primarily driven by the seasonal changes in insolation. On an annual basis, FGOALS-f3-L shows a slight cooling of the mean annual temperature over almost all the globe at 6 ka, whereas FGOALS-g3 shows noticeable warming at mid-to-high latitudes in both the Northern and Southern Hemisphere. FGOALS-f3-L and FGOALS-g3 both simulate global cooling, of ?0.5°C and ?0.2°C, respectively, relative to 0 ka, which differs from the +0.5°C derived from the paleo-reconstruction (Kaufman et al., 2020). Model–data comparisons show that FGOALS-f3-L underestimates the warming in the mean annual temperature over most regions in the mid-to-high latitudes of the Northern Hemisphere, but slightly overestimates the warming in East Asia (Fig. 4a). FGOALS-g3 also underestimates the warming over western Europe, central Asia, Alaska, and eastern North America, but to a lesser extent. A pronounced overestimation can be identified in eastern Europe, central Russia, East Asia, and central North America (Fig. 4b). Both models show a similar underestimation over Africa.

Figure4. Changes in mean annual temperature (MAT, °C) and mean annual precipitation (MAP, mm yr?1) relative to the proxy data for (a, c) FGOALS-f3-L and (b, d) FGOALS-g3.

Figure4. Changes in mean annual temperature (MAT, °C) and mean annual precipitation (MAP, mm yr?1) relative to the proxy data for (a, c) FGOALS-f3-L and (b, d) FGOALS-g3.Because the seasonal changes in solar insolation are larger at 127 ka than at 6 ka, the response of the surface temperature is expected to be larger during the Last Interglacial. Summertime warming exceeds 3°C in the mid-to-high latitudes of the Northern Hemisphere continents in CAS-FGOALS models (Fig. 2b). The land in the Southern Hemisphere also shows warming in response to the positive insolation anomalies, but with a smaller amplitude. Similar to the changes at 6 ka, the warming is about twice as large in FGOALS-g3 as in FGOALS-f3-L. The warming of surface temperature in summer is weaker over the tropical and subtropical oceans; differences can be identified in the Southern Ocean, with cooling in FGOALS-f3-L and warming in FGOALS-g3. A large amount of cooling prevails over the continents during boreal winter, particularly in Africa and Asia, and extends to the ocean in response to the negative insolation anomalies. FGOALS-g3 shows pronounced warming in the Arctic and the Southern Ocean, which is barely observed in FGOALS-f3-L. On an annual basis, FGOALS-f3-L shows slight warming in the Arctic, North Atlantic and western Europe, but cooling elsewhere, with maximum cooling over the monsoon regions, whereas FGOALS-g3 reproduces the amplification of the mean annual temperature in mid-to-high latitudes in both hemispheres. Cooling over the African and Indian monsoon regions and almost neutral changes in the tropics are shown in both CAS-FGOALS datasets.

Capron et al. (2017) summarized the regional changes in surface temperature at 127 ka deduced from the datasets by Capron et al. (2014) and Hoffman et al. (2017). Following the definition of ocean basins in Capron et al. (2017), the regional sea surface temperature (SST) averages of the North Atlantic Ocean (30–60°N, 50°W–0°) or Southern Ocean (40–60°S, 5°W–180°E) are calculated from the model simulations. The surface temperature is also calculated for the Antarctic averaged over the region (70°–80°S, 5°W–130°E), which covers the paleo-records. Table 3 summarizes the model–data comparisons. FGOALS-f3-L underestimates the summer SST, but captures the slight annual cooling in the North Atlantic, whereas FGOALS-g3 simulates the summer SST reasonably well, but overestimates the annual SST. Neither CAS-FGOALS models can reproduce the pronounced warming in the Southern Ocean and the Antarctic. FGOALS-f3-L simulates regional cooling over most of the Southern Hemisphere (Fig. 2b). Although FGOALS-g3 simulates the warming, the amplitude is weaker than the paleo-records.

| Sector | FGOALS-f3-L | FGAOLS-g3 | Reference | |

| Capron et al. (2014) | Hoffman et al. (2017) | |||

| North Atlantic summer SST | 0.53 ± 0.54 | 1.24 ± 0.69 | 1.1 ± 0.7 | 1.9 ± 1.7 |

| North Atlantic annual SST | ?0.15 ± 0.56 | 0.58 ± 0.58 | ? | ?0.2 ± 1.4 |

| Southern Ocean summer SST | ?0.34 ± 0.34 | 0.68 ± 0.39 | 1.8 ± 0.8 | 1.6 ± 0.9 |

| Southern Ocean annual SST | ?0.32 ± 0.36 | 0.74 ± 0.4 | ? | 2.7 ± 0.8 |

| Antarctic annual air temperature | ?0.18 ± 0.25 | 0.91 ± 0.24 | 2.2 ± 1.4 | ? |

Table3. The 127 ka regional changes in surface temperature extracted from Capron et al. (2017). Area-weighted SST values are calculated for the North Atlantic (30°–60°N, 50°W–0°) and Southern Ocean (40°–60°S, 5°W–180°E) from the model simulations. The surface temperature is also calculated for the Antarctic averaged in the region (70°–80°S, 5°W–130°E) that covers the paleo-records (units: °C).

2

3.2. Response of precipitation

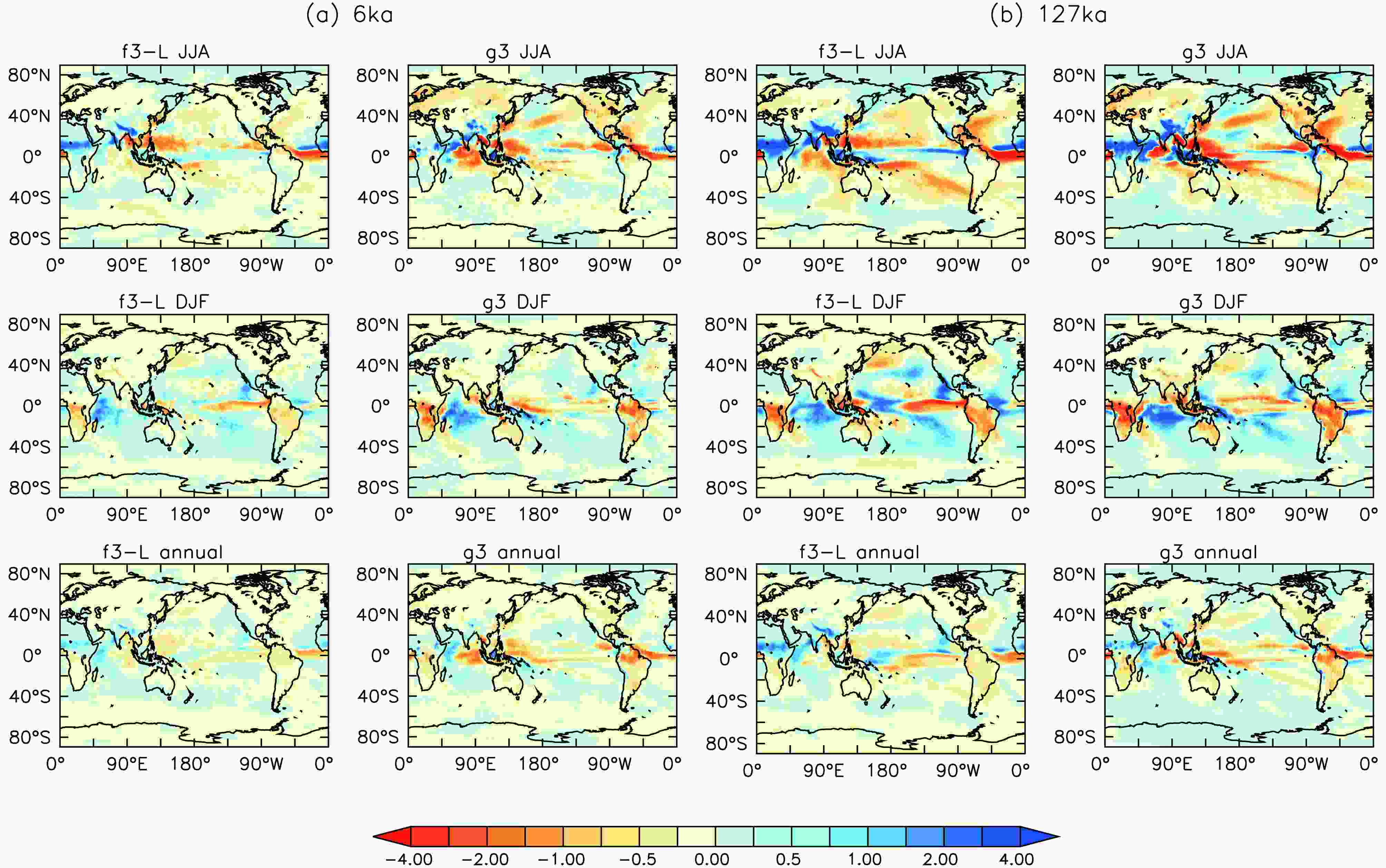

The changes in precipitation shown in Fig. 3 indicate the response of the global hydrological cycle to the changes in solar insolation and the redistribution of moisture in the two interglacial epochs. Pronounced changes are observed as an enhanced summer monsoon in the Northern Hemisphere and hydrological changes in the tropical and subtropical Pacific, such as the shifts in the Intertropical Convergence Zone and variations in the South Pacific Convergence Zone.The patterns of changes in precipitation are similar between 6 and 127 ka, but with different amplitudes for both CAS-FGOALS models. Compared with 0 ka, FGOALS-f3-L simulates a northward shift in the West African monsoon with an increase in rainfall of 60% and 130% at 6 ka and 127 ka, respectively. FGOALS-g3 shows a similar expansion of the monsoon, but the changes in summer precipitation are smaller at 20.6% and 93.4%, respectively. The South Asian monsoon rainfall is increased by 6.4% and 24% at 6 ka and 127 ka in FGOALS-f3-L and by 4% and 10.8% in FGOALS-g3. The models show different changes in the East Asian monsoon region at 6 ka. FGOALS-f3-L shows a small reduction in rainfall (?2.6%), whereas FGOALS-g3 shows an increase of 1.4%. By contrast, the East Asian monsoon rainfall at 127 ka is increased by 12.7% and 5.8% in FGOALS-f3-L and FGOALS-g3, respectively. Summer precipitation also increases along the equatorial eastern Pacific, but decreases in the equatorial Atlantic, the central Indian Ocean, the North Pacific, and the South Pacific Convergence Zone. The major difference between the two models is that FGOALS-g3 simulates reduced summer precipitation over the warm pool, and the northward shift in the Intertropical Convergence Zone is more significant than that in FGAOLS-f3-L. Winter precipitation shows a similar pattern to the summer precipitation, but with a reversed sign. Precipitation increases over the Indian Ocean, the South Pacific Convergence Zone, and the Atlantic Ocean, but decreases over South Africa, Australia, South America, and the equatorial Pacific Ocean (Fig. 3).

Although the models qualitatively reproduce the increase in the summer monsoon at 6 ka, the model–data comparisons show a difference in the precipitation amount between them. The changes in the mean annual precipitation (MAP) are underestimated over almost the entire globe, except for eastern North America (Fig. 4). The regional changes in the MAP are about 220–340 mm yr?1 less in the West African and East Asian monsoon regions relative to the proxy data. The MAP in the South Asian monsoon region is underestimated by about 200 and 35 mm yr?1 in FGOALS-f3-L and FGOALS-g3, respectively. At 127 ka, the semi-quantitative proxy data summarized by Scussolini et al. (2019) show wetter conditions over central and northern Africa, South and Northeast Asia, southern and eastern Europe, the western midlatitudes and northwestern parts of North America, and the northernmost part of South America. Both CAS-FGOALS models simulate the increased precipitation in central and northern Africa, southern and eastern Europe, and South and Northeast Asia reasonably well, supporting the wetter conditions in the proxy data (Fig. 4). The models also reproduce the seasonal precipitation signals at 127 ka, such as the summer aridity in southern Europe (Milner et al., 2012) and the northward extension of the Asian summer monsoon (Cheng et al., 2012). Elsewhere, preliminary analyses of the model results are inconclusive compared with the proxy data and require further assessment.

2

3.3. Response of sea ice

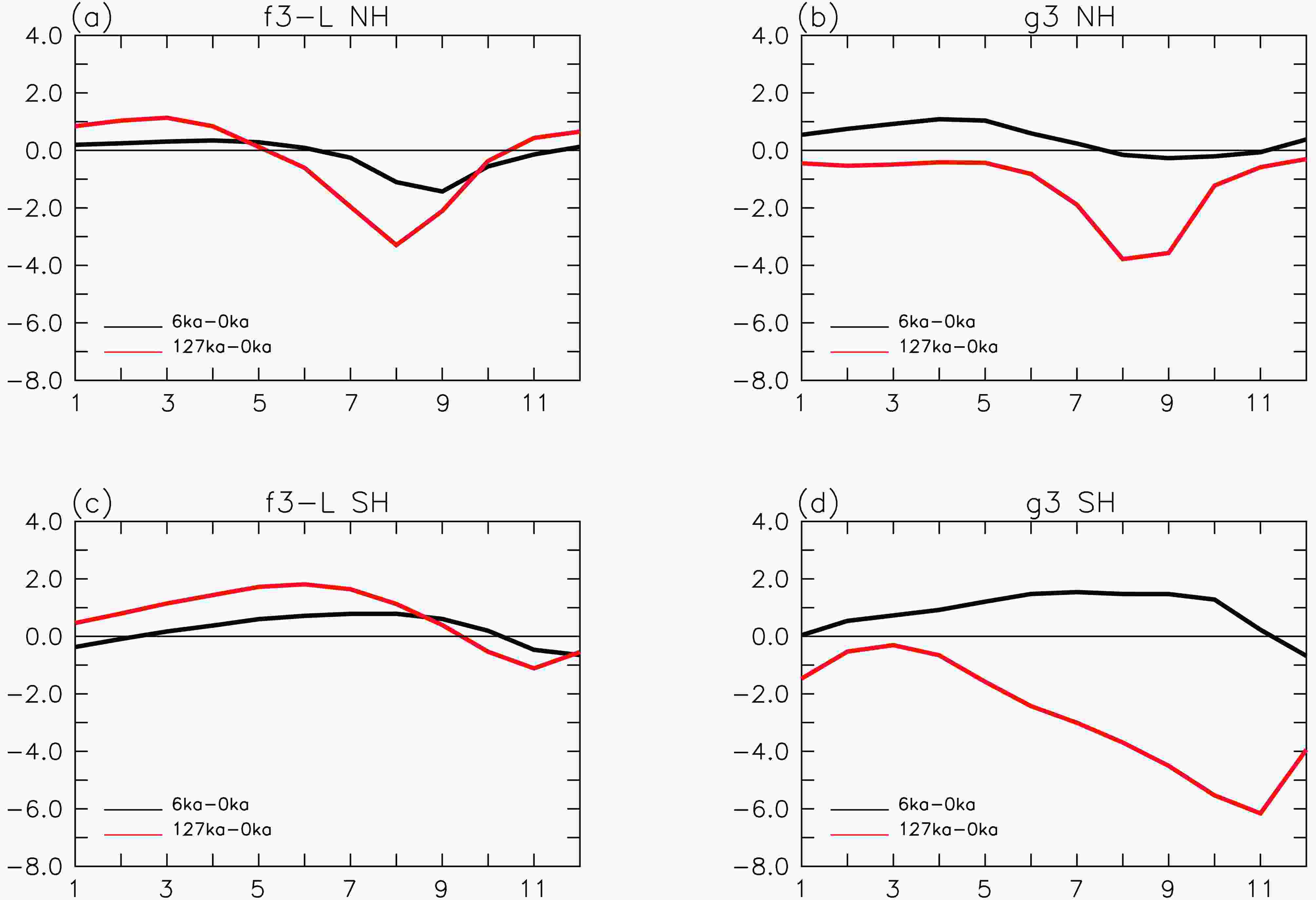

The changes in the extent of sea ice follow the solar insolation anomalies reasonably well in both hemispheres for the two interglacial simulations (Fig. 5). The seasonal cycle of Arctic sea ice is enhanced in response to the positive insolation anomalies in boreal summer in both CAS-FGOALS simulations, although different behaviors can be identified. FGOALS-f3-L simulates a slight increase in the extent of sea ice during boreal winter in response to negative insolation anomalies, with a larger amplitude at 127 ka. The areal extent of Arctic sea ice is less from July to November at 6 ka and from May to November at 127 ka as a result of the positive insolation anomalies in boreal summer (Fig. 5a). FGOALS-g3 shows a larger response to the negative insolation anomalies with a larger areal extent of sea ice from December to June, but the decrease in Arctic sea ice in boreal autumn is less significant than that in FGOALS-f3-L at 6 ka (Fig. 5b). The large decrease in Arctic sea ice in August and September is also seen in FGOALS-g3 at 127 ka, although the annual mean sea-ice extent is less than that at 0 ka as a result of the pronounced warming of the mean annual temperature. The changes in Antarctic sea ice also follow the seasonal anomalies in solar insolation (Figs. 5c and d). Figure5. Simulated changes in the annual cycle of the extent of sea ice in the (a, b) Northern Hemisphere (NH) and (c, d) Southern Hemisphere (SH) for (a, c) FGOALS-f3-L and (b, d) FGOALS-g3 (units: 106 km2).

Figure5. Simulated changes in the annual cycle of the extent of sea ice in the (a, b) Northern Hemisphere (NH) and (c, d) Southern Hemisphere (SH) for (a, c) FGOALS-f3-L and (b, d) FGOALS-g3 (units: 106 km2).2

3.4. Changes in El Ni?o–Southern Oscillation

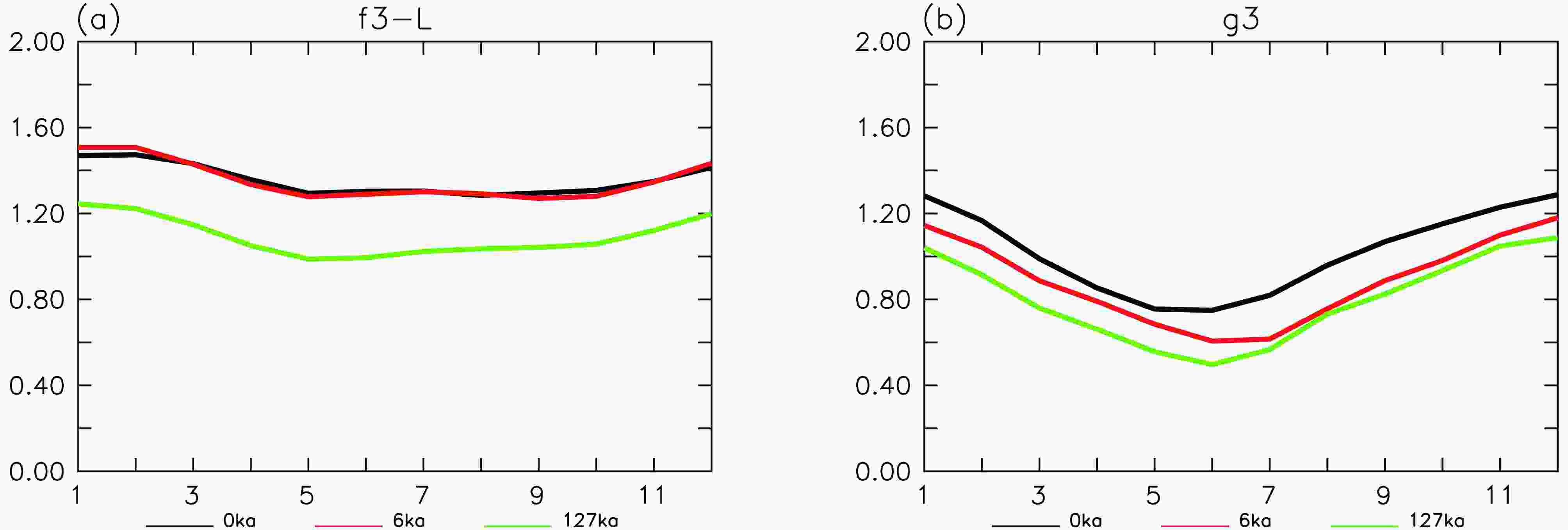

A number of studies of paleoclimate proxy data suggest weaker variations of El Ni?o–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) during the mid-Holocene (Rodbell et al., 1999; Cole, 2001; Karamperidou et al., 2015; White et al., 2018). Model studies, including the PMIP2 and PMIP3 paleoclimate simulations, also show evidence of damping of ENSO at 6 ka relative to the present day (Zheng et al., 2008; Zheng and Yu, 2013; An and Choi, 2014; Emile-Geay et al., 2016; Chen et al., 2019). Paleoclimate proxy data for the variability of ENSO before the Holocene are relatively scare, but some records suggest that ENSO varied in interglacial times (Tudhope et al., 2001) and model results show a weaker variation in ENSO in the Last Interglacial (An et al., 2017).Both CAS-FGOALS models simulate a stronger ENSO at 0 ka than in the observations, although the ENSO periodicities are similar at about three years (Table 4). A weaker amplitude and broader periodicity of ENSO is simulated in the two interglacial experiments, except for the amplitude of ENSO at 6 ka simulated by FGOALS-f3-L (Table 4). The changes at 127 ka are more significant than those at 6 ka, implying a larger response of the tropical climate to the seasonal changes in solar insolation. Figure 6 shows that the variations in the monthly SST anomalies in the Ni?o3 regions peak in boreal winter in both epochs. FGOALS-g3 shows significant ENSO damping at 6 ka, whereas there is almost no change in FGOALS-f3-L. Such differences might be related to different changes in the mean climate in response to external forcing. Both CAS-FGOALS simulations show an overall damping throughout the year at 127 ka, although detailed analyses are required to determine the mechanisms of change in the characteristics of ENSO.

| Experiment | Ni?o3 (3.4) index (°C) | ENSO cycle (yr) | |||

| FGOALS-f3-L | FGOALS-g3 | FGOALS-f3-L | FGOALS-g3 | ||

| piControl (0 ka) | 1.298 (1.331) | 0.968 (0.944) | 3.0–3.3 | 2.7–3.0 | |

| midHolocene (6 ka) | 1.296 (1.327) | 0.827 (0.782) | 3.0–3.8 | 2.8–3.2 | |

| lig127k (127 ka) | 1.037 (1.088) | 0.742 (0.705) | 3.1–4.0 | 2.4–3.6 | |

Table4. Basic information about the amplitude and period of ENSO in the simulations of piControl and the two interglacial epochs.

Figure6. Standard deviation of monthly SST anomalies in the Ni?o3 region for (a) FGOALS-f3-L and (b) FGOALS-g3 (units: °C).

Figure6. Standard deviation of monthly SST anomalies in the Ni?o3 region for (a) FGOALS-f3-L and (b) FGOALS-g3 (units: °C).2

3.5. Discussion

These preliminary analyses show that both CAS-FGOALS models simulate reasonable responses to the changes in solar insolation and that the results are qualitatively comparable with some aspects of the proxy data, such as warming in mid-to-high latitudes or changes in the monsoon systems. There are, however, substantial disagreements within the models and between the models and proxy data. Previous studies have suggested that the biases in the control simulations may influence the response to external forcings (Braconnot et al., 2012; Harrison et al., 2014) and affect the pattern and magnitude of the simulated changes. A comprehensive review of the biases of the model itself would contribute to the interpretation of the climate changes in the past. Meanwhile, the uncertainties in the proxy data should also be considered when applying model–data comparisons. Therefore, further studies are necessary to understand the mechanisms of the changes in the two interglacials, as well as the disagreements in the models and between the models and proxy data.All the model outputs are prepared in their original grid, except for FGOALS_f3_L. Because the original atmospheric model grid of FGOALS_f3_L is in the cube–sphere grid system, the one-order conservation interpolation is applied to change the data into a global longitude–latitude grid of 1.25° × 1°. Hybrid level coefficients are also provided for the calculation of pressure at the model layers (He et al., 2019). These data can be easily processed with common programming languages (e.g., Fortran, C and Python), professional operators (CDO and NCO), and data visualization and analysis software such as FERRET and NCL.

Acknowledgements. This study was supported by the National Key R&D Program for Developing Basic Sciences (Grant Nos. 2016YFC1401401 and 2016YFC140 1601), the Strategic Priority Research Program of Chinese Academy of Sciences (Grant Nos. XDA19060102 and XDB42000000) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants Nos. 91958201, 41530426, 41576025, 41576026, 41776030, 41931183, 41976026 and 41376002). The authors acknowledge the technical support from the National Key Scientific and Technological Infrastructure project “Earth System Science Numerical Simulator Facility” (EarthLab).

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (