王明凤1,2, 曹佳莉1,2, 袁权2

, 夏宁邵2

, 夏宁邵2 1. 厦门大学生命科学学院, 福建 厦门 361102;

2. 厦门大学国家传染病诊断试剂与疫苗工程技术中心, 福建 厦门 361102

收稿日期:2019-02-13;修回日期:2019-03-24;网络出版日期:2019-07-11

基金项目:国家自然科学基金(81672023)

*通信作者:袁权, Tel:+86-592-2880627, Fax:+86-592-2181258, E-mail:yuanquan@xmu.edu.cn.

摘要:慢性乙型肝炎病毒(Hepatitis B virus,HBV)感染是严重威胁人类生命健康的世界性公共卫生问题。基于现有抗HBV药物的治疗策略,仅能在极少部分患者中实现慢性乙肝的功能性治愈。发展更为有效的抗HBV药物,需要更加透彻全面地认识各个病毒组分和关键宿主因子在HBV感染和复制生命周期中发挥的功能和机制,并在此基础上发现鉴定新的治疗靶点。支持HBV体外感染和复制的细胞模型,是研究HBV生活史的重要工具,并在治疗新靶点的发现和候选药物功效评估等研究工作中发挥关键作用。本文对支持HBV感染和复制细胞模型的新近研究进展进行梳理分析,并对这些模型的应用特点和局限性、新近研究进展和未来发展方向进行系统阐述和讨论。

关键词:乙型肝炎病毒复制感染细胞模型

Cell models for studying HBV infection and replication in vitro

Mingfeng Wang1,2, Jiali Cao1,2, Quan Yuan2

, Ningshao Xia2

, Ningshao Xia2 1. College of Life Sciences, Xiamen University, Xiamen 361102, Fujian Province, China;

2. National Institute of Diagnostics and Vaccine Development in Infectious Diseases, Xiamen University, Xiamen 361102, Fujian Province, China

Received: 13 February 2019; Revised: 24 March 2019; Published online: 11 July 2019

*Corresponding author: Quan Yuan, Tel: +86-592-2880627; Fax: +86-592-2181258; E-mail:yuanquan@xmu.edu.cn.

Foundation item: Supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81672023)

Abstract: Chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is a worldwide public health problem that poses a serious threat to human health. Currently, only a very small fraction of patients can achieve functional cure based on the existing treatment strategies of anti-HBV drugs. The development of more effective drugs against HBV certainly requires a more comprehensive understanding on the roles and mechanisms of each viral component and its related host factors in viral life cycle, and therefore providing scientific clues for further identification of novel therapeutic targets. In vitro cell models supporting HBV replication and infection are important tools for basic researches of HBV life cycle, and play essential roles in the identification of novel anti-HBV targets and efficacy evaluation of drug candidate. In this review, we summarize the recent research advances on the cell culture models supporting HBV infection and replication, and systematically illustrate and discuss their application characteristics and limitations and highlight perspectives for further developments.

Keywords: Hepatitis B virusreplicationinfectioncell models

乙型肝炎病毒(Hepatitis B Virus,HBV)是一种带有包膜的DNA病毒,有嗜肝性,可以造成人类持续性病毒感染(persistent viral infection)。慢性HBV感染(chronic HBV infection)是世界范围内最为严重的公共卫生问题之一,是导致肝硬化和原发性肝细胞癌(hepatocellular carcinoma,HCC)的主要原因。尽管目前已有预防性疫苗可有效预防新发HBV感染,但在全世界范围内仍有约2.48亿慢性HBV感染者,且难以被现有治疗手段治愈[1]。慢性乙肝感染者罹患肝癌的风险较无HBV携带者高5–100倍[2-3]。虽然目前治疗慢性HBV的药物(如核苷类似物、干扰素等)可以减少癌症的发展[4],但在治疗的前五年,发展成为肝癌的风险仍然高于正常水平[5-6],特别是晚期肝病患者。慢性乙肝感染的最佳临床治疗终点是使患者达到HBsAg血清学阴转或血清学转换,达到这一终点的患者发展为重症肝炎(肝衰竭)、肝硬化和肝癌等终末期肝病的风险大大降低,因此可被视为实现慢性乙肝的“临床治愈”。然而,现有基于干扰素类和核苷/核苷酸类似物及其组合的临床治疗策略虽能控制病毒复制,缓解疾病进展,但并不能有效实现临床治愈(通常 < 5%)。因此,发展更为有效治疗药物以实现慢性乙肝患者的有效临床治愈,是全球乙肝防治科技工作者在未来5–20年内面临的现实挑战。

支持HBV感染和复制的体外细胞模型,是研究HBV生活史的重要工具,并在治疗新靶点发现和候选药物功效评估等研究工作中发挥关键作用。近年来,HepaRG、HepG2-NTCP、干细胞分化来源的类肝细胞等在HBV相关研究中广泛应用于病毒宿主相互作用[7-8]、HBV感染复制相关宿主因子的发现鉴定[8-9]、针对HBV生活周期关键节点的靶向药物筛选[10-13]等。本文对支持HBV相关体外细胞模型的新近研究进展进行总结归纳,并详细分析这些模型在HBV研究中的应用现状和局限性,以进一步探讨构建更为完善的HBV细胞模型。

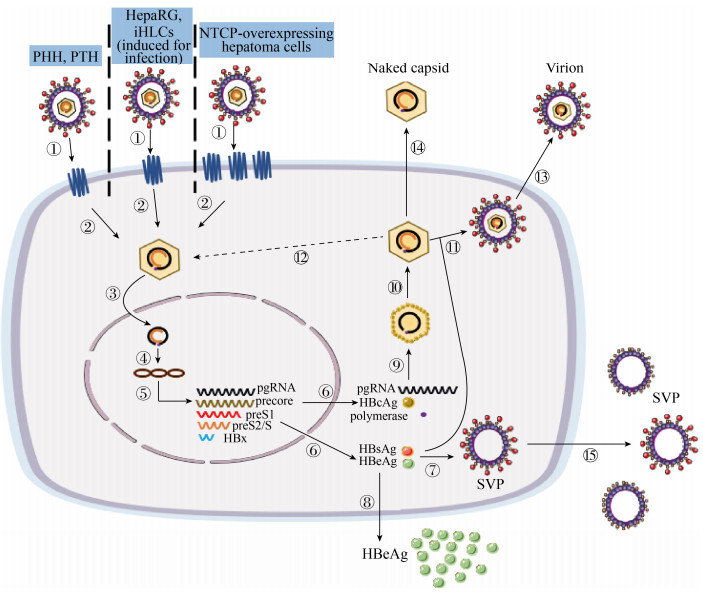

1 HBV体外感染模型 HBV的感染过程主要包括:病毒颗粒与细胞的结合、脱外膜蛋白释放核衣壳入胞、rcDNA在核内形成cccDNA、5种形式RNA的转录、前基因组RNA (pgRNA)作为模板逆转录并最终形成rcDNA回补cccDNA池、HBV相关蛋白的翻译与成熟、病毒颗粒的组装与释放等(图 1)。

|

| 图 1 HBV体外感染细胞模型的生命周期模式图 Figure 1 Life cycle pattern of cell models for HBV infection in vitro. ① The virions bind to the NTCP receptor on the cell surface; ② uncoating surface protein, then releases the nucleocapsid into the cell; ③ rcDNA is released into the nucleus; ④ rcDNA deproteinizes, then the positive strand is filled to form a supercoiled cccDNA; ⑤ cccDNA is used as a template to transcribe 5 kinds of mRNA; ⑥ protein translation in the cytoplasm; ⑦ S proteins are assembled into subviral empty envelope particles (SVP); ⑧ the secretion of e antigen; ⑨ polymerase protein binds to pgRNA to initiate reverse transcription, then forms negative-strand DNA and immature nucleocapsid; ⑩ DNA positive chain synthesis to form intact rcDNA (mature nucleocapsid); ? formation of mature virions; ? a part of nucleocapsids replenish cccDNA pool; ? releases of mature virus particles; ? a part of nucleocapsids is released in a naked form (naked capsid); ? subviral empty envelope particles (SVP) are released outside the cell. |

| 图选项 |

1.1 原代肝细胞 人类的肝细胞是HBV的特异性宿主。在相当长一段时间里,人类原代肝细胞(PHH)是唯一支持HBV体外感染的研究模型[14]。但是,人原代肝细胞来源有限,体外培养技术要求较高且不能连续扩增,极大地限制了其在HBV研究中的应用[15]。一般而言,在体外培养条件下,PHH的肝细胞表型会在铺板培养的数天内快速改变,进而导致其支持HBV感染的能力降低[14]。此外,HBV对于人原代肝细胞的感染有一定的宿主遗传背景依赖性,不同供体之间的高度异质性也影响了基于PHH细胞的HBV感染研究结果的可重复性[16]。针对PHH体外培养表型维持难的问题,Bhatia等新近构建了一种称为微型共培养系统(micro-patterned co-cultured,MPCC)的培养体系,该系统是将200–400个PHH在精确的微尺度结构中与3T3小鼠胚胎成纤维细胞共培养至少9 d,使得原代肝细胞恢复其极性并形成胆管网络,在该培养体系中的PHH可保持数周正常的存活力和代谢功能[17]。有研究表明MPCCs可支持HBV的感染[18]。考虑到人肝脏结构的复杂性以及体外培养条件下细胞之间的相对位置和相互作用,相比2D模式的培养,3D模式的培养体系或许更接近真实情况下的HBV感染[19]。除PHH外,树鼩(Tupaia belangeri)的原代肝细胞(PTH)也可以支持HBV的感染[20]。2013年,北京生命科学研究所李文辉教授团队的Yan等利用树鼩的原代肝细胞模型发现鉴定出人钠离子-牛磺胆酸共转运蛋白(sodium taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide,NTCP)是HepG2等常用肝癌细胞株中缺少的HBV感染所需的功能性受体[9]。PTH模型也可被用于研究NA类药物抗HBV反应的作用机制[21]以及从病人血清中分离出来的不同HBV毒株的功能表型[22]。与PHH类似,PTH也存在来源限制和体外培养表型改变的问题,但是原代肝细胞依旧是研究HBV感染中在生理上最接近自然状态的易感细胞,它具有HBV天然宿主的典型特征和正常的胞内天然免疫应答[23-24],是研究病毒宿主相互作用、评估药物抗HBV作用最为可靠的模型(表 1)。

表 1. HBV体外感染细胞模型 Table 1. Cell models for studying HBV infection in vitro

| Cell models | Source or feature | Advantages | Disadvantages | References |

| PHH | Human liver tissue | Research for metabolism and innate immune response after HBV infection; support full HBV life cycle; natural host of HBV | Costly; limited resources; difficult to culture; short life; large heterogeneity between donors; low infection efficiency | [14-15] [16] |

| PTH | Liver tissue of tree shrew | Support HBV infection similar to human hepatocytes; has natural immune response against HBV | Low infection efficiency; non-human cells; limited resources; phenotypic changes cultured in vitro | [9, 20] |

| HepaRG | Derived from a HCV- induced liver tumor | Support full HBV life cycle; exhibit some hepatic functions | Long time for induced differentiation; low infection efficiency; little or no cccDNA amplification | [25, 27] |

| NTCP-overexpressing hepatoma cell line | Integration of exogenous NTCP | Easy access; unlimited supply; good reproducibility; easy to operate; higher infection efficiency; support complete life cycle of HBV; platform for virus entry inhibitor screening | High MOI for infection; limited infection transmission; less cccDNA formation; lack of natural interaction between virus and host; greatly different from normal physiological liver performance | [6, 9, 31, 34, 48-50] |

| HLCs or hiHep | Stem cell differentiation or non-hepatocyte transdifferentiation | Support full HBV life cycle; exhibit some hepatic functions; unlimited supply; suitable for genetic manipulation | Complex and long-term differentiation; can’t represent complete phenotype profile of primary adult hepatocytes; low infection efficiency | [53-56] |

表选项

1.2 HepaRG细胞 HepaRG细胞是从一位慢性丙型肝炎病毒感染的女性肝癌患者的肝脏肿瘤中分离出来的具有分化潜能的肝祖细胞系[25]。相比于其他肝癌来源的细胞系,HepaRG细胞保持了大量的生理性肝功能,并表现出与原代肝细胞更接近的基因表达模式。经过2周的2% DMSO诱导分化后,HepaRG细胞可以分化为类肝细胞和类胆管细胞(各约50%),其中类肝细胞可支持HBV的感染[25]。相比于原代肝细胞,HepaRG可多次传代,分化后的HepaRG细胞还能进行逆分化重新回复到肝祖细胞阶段进行扩增,感染重现性也显著提高。有鉴于此,HepaRG/HBV系统可以用来筛选抑制HBV感染的小分子,如ezitimibe[26]。研究证实,分化后的HepaRG细胞能支持完成HBV完整生命周期,并支持cccDNA的合成和持续[27]。由于分化后的HepaRG细胞具备较为完善的Ⅰ相和Ⅱ相代谢酶活力,这一细胞也被广泛运用于药物代谢相关研究。除在体外HBV感染中的运用,我们实验室近期发表的研究表明,通过多种小分子组合优化的诱导程序分化出的HepaRG类肝细胞可在FRGS小鼠中实现一定程度的人源化重建,并支持体内HBV感染[28]。

Schulze等利用HepaRG细胞阐明了在HBV感染细胞起始步骤中硫酸乙酰肝素糖蛋白(HSPGs)的重要性[29]。Sureau和Salisse等用HepaRG细胞找到了位于HBV膜蛋白抗原环区的硫酸乙酰肝素结合位点,该位点对于HBV的感染起着至关重要的作用[30]。Ni等通过比较已分化的和原始HepaRG细胞的转录组模式,证实了NTCP作为细胞受体在HBV感染过程中的重要作用[31]。Macovei等基于HepaRG细胞的研究发现小窝蛋白-1 (caveolin-1)在HBV病毒粒子内吞过程中的作用[32]。此外,大量研究发现HBV的感染可在一定程度上促发HepaRG细胞Ⅰ型干扰素应答[33],提示这一细胞可用于HBV感染相关天然免疫识别和应答的宿主因子研究。尽管基于HepaRG细胞的HBV感染模型具有诸多优点,但也存在一些不足:如感染需要一个较长的培养和分化周期(大约4周)、实际感染效率较低且需较高的感染剂量(> 1000 GE/cell)、很少的甚至几乎没有cccDNA的扩增[27]等,这些因素都极大地限制了HepaRG在高通量大规模抗HBV药物筛选中的应用(表 1)。

1.3 外源表达NTCP的肝癌细胞系 NTCP是多次跨膜的胆汁酸转运蛋白,特异性地在肝细胞膜表面表达,能与HBV病毒外膜蛋白pre-S1区域特异性结合[6],是常用肝癌细胞系(如Huh7、HepG2等)中表达缺失的HBV功能性受体[9],由于缺乏内源性NTCP表达,HepG2等广泛运用于生物医学实验室研究的传代细胞系,在正常培养条件下不能支持HBV感染,但在其中外源性表达NTCP可恢复其HBV易感性[9, 31]。由于肝癌细胞易培养、增殖快的特点,外源表达NTCP的肝癌细胞系为HBV的体外感染研究相对高效的细胞模型。值得注意的是,同样外源表达hNTCP的HepG2细胞(HepG2-NTCP)比Huh7 (Huh7-NTCP)的感染效率更高,可能提示两种细胞在cccDNA形成能力或者其他影响HBV感染的基因表达水平等方面存在差异[9, 34]。有研究表明HepG2-NTCP细胞对细胞培养来源的HBV病毒(cell culture derived HBV,ccHBV)易感性要显著高于慢性HBV感染者血清来源的HBV病毒(patient’s serum derived HBV,sHBV),这与HepaRG细胞上的感染表现相反。此外,ccHBV在HepG2-NTCP细胞中的感染常表现为HBeAg/HBsAg分泌水平比例较高,这与病毒在生理条件和HepaRG、PHH感染模型中的感染特征也有区别[35]。Qiao等和Ni等发现使用2%以上的DMSO处理HepG2-NTCP细胞能提高其对细胞来源HBV的易感性,显著提升感染后HBeAg的分泌水平和胞内HBV复制水平[31, 36],但是也有研究发现,使用DMSO处理细胞并不能提高感染后HepG2-NTCP细胞的HBsAg分泌水平,也不能显著改善其对病人血清来源的HBV的易感性[35]。

尽管NTCP是HBV感染的重要受体,但外源表达hNTCP的鼠肝细胞并不能支持HBV的有效感染[37-39] (表 1)。Lempp等发现存在于病毒入胞后和以cccDNA为模板进行转录的步骤之间的某些宿主依赖性因子的缺乏是外源表达hNTCP的鼠肝细胞不能有效支持HBV感染的关键因素[40]。近期有研究发现,外源表达hNTCP的鼠肝细胞系AML12能一定程度地支持体外HBV感染,该细胞来源于过表达人转化生长因子α(hTGFα)的转基因小鼠[41-42],进一步研究AML12和其他鼠肝细胞/细胞系中存在的影响HBV感染的关键差异,或有助于发现除NTCP外决定HBV宿主特异性的重要分子,如获突破则可能发展出支持HBV感染的小动物模型,进而为乙肝相关研究提供便捷高效的体内模型。

虽然尚有不足,以HepG2-NTCP为代表的外源表达NTCP的肝癌细胞系因其易操作、短周期、重现性佳的优势为HBV研究提供了强大而便捷的工具(表 1)。Chunkyu等利用HepG2-NTCP细胞发现DEAD盒RNA解旋酶家族成员DDX3是HBV宿主限制因子,可阻碍cccDNA的转录[43]。Verrier等利用Huh7-NTCP细胞发现GPC5作为肝细胞表面的附着因子在HBV感染入胞过程中起着重要作用[44]。有研究基于这一模型发现,一些分子可以通过与NTCP的直接相互作用,如环孢菌素A[45]及其衍生物[46],或者通过下调NTCP的表达,如白介素6 (interleukin 6,IL6)[47],来抑制HBV的入胞。外源表达NTCP的肝癌细胞系也为筛选靶向入胞过程的抗病毒药物提供了支持,如雷帕霉素及其衍生物[48]、vanitaracin A[49]、环孢菌素A及厄贝沙坦[50]等均已在这一系统中证实了其对HBV的感染抑制活性。Nishitsuji等将改造后的3种HBV质粒共转肝癌细胞,培养上清经纯化获得具有感染能力并携带NanoLuc报告基因的重组HBV病毒,感染HepG2-NTCP细胞后通过NanoLuc的表达测定来评价HBV病毒从入胞到DNA转录的早期生命周期的活性,该系统将为大规模筛选针对HBV生命周期早期阶段的抗病毒药物提供工具[10, 51-52]。

1.4 干细胞定向分化或非肝细胞转分化来源的类人肝细胞 2006年,日本科学家山中伸弥(Yamanaka)通过外源导入Oct3/4、Sox2、Klf4和c-Myc可将终末分化的皮肤成纤维细胞逆分化成多能干细胞,即诱导多能干细胞(induced pluripotent stem cells,iPSC)[53]。进一步的研究表明,通过人胚胎干细胞或诱导多能干细胞的分化可以获得功能性的类人肝细胞(human hepatocyte-like cells,HLCs)。已有多项研究表明,iPSC来源的HLCs能支持体外HBV感染[54]。近期,我们实验室的研究也表明,iPSC来源的HLCs能在FRGS小鼠中实现肝重建并支持HBV的体内感染[55]。除干细胞定向分化来源的类人肝细胞(stem cell-derived hepatocyte-like cells)外,我国惠利健教授研究团队建立了可绕开干细胞阶段,直接将成纤维细胞分化成类人肝细胞的技术体系,他们的研究发现将FOA3、HNF1A、HNF4A三个转录因子转入人胚胎成纤维细胞可以将其转分化为类人肝细胞(human induced hepatocytes,hiHep)[56]。研究证实,hiHep细胞具有与PHH类似的基因表达谱和代谢功能。本实验室新近的一些研究数据(未发表)也表明,hiHep细胞能在体外支持HBV的感染和复制。总体上,干细胞定向分化或非肝细胞转分化来源的类人肝细胞为HBV的体外感染复制模型提供了新的细胞来源,这类细胞在某些方面相比于基于肿瘤细胞的HBV模型更为接近真实生理状态,但也存在操作周期长、感染效率低等不足,其在HBV研究领域广泛应用可能需要进一步完善优化(表 1)。

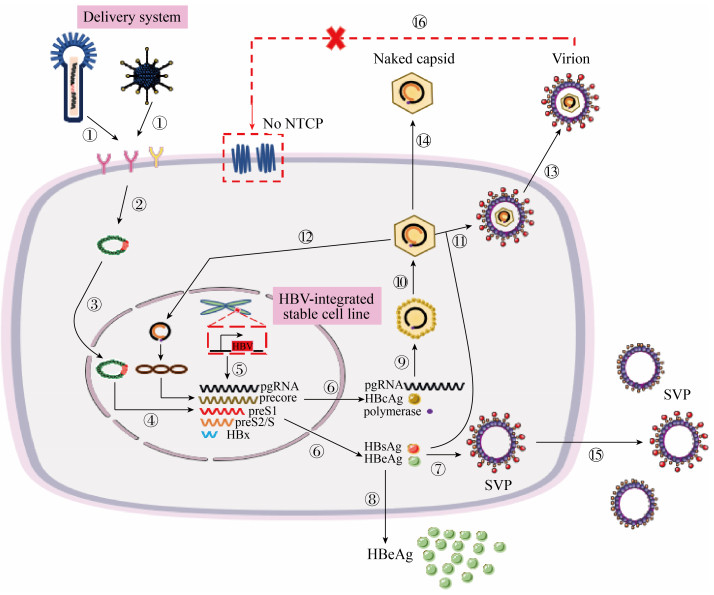

2 HBV体外复制模型 与感染模型不同的是,在HBV复制模型中缺少NTCP等HBV相关受体的表达,五种形式HBV RNA的转录最初来源于整合于宿主细胞染色体或者其他载体上的HBV基因组(图 2)。

|

| 图 2 HBV体外复制细胞模型的生命周期模式图 Figure 2 Life cycle pattern of cell models for HBV replication in vitro. ① baculovirus or adenovirus containing HBV genome bind to releated receptor on the cell surface; ② releasing viral DNA into cytoplasm; ③ viral DNA is transported into the nucleus; ④ the genome of HBV is transcribed to form five kinds of mRNA; ⑤ the cell line stably integrating the HBV genome initiates transcription (or under the control of tetracycline); ⑥ protein translation in the cytoplasm; ⑦ S proteins are assembled into subviral empty envelope particles (SVP); ⑧ the secretion of e antigen; ⑨ polymerase protein binds to pgRNA to initiate reverse transcription, then forms negative-strand DNA and immature nucleocapsid; ⑩ DNA positive chain synthesis to form intact rcDNA (mature nucleocapsid); ? formation of mature virions; ? a part of nucleocapsids replenish cccDNA pool; ?releases of mature virus particles; ? a part of nucleocapsids is released in a naked form (naked capsid); ? subviral empty envelope particles (SVP) are released outside the cell; ? cell can't be infected by HBV without NTCP expression. |

| 图选项 |

由于HBV的感染和复制具有肝细胞嗜性,所以常用于研究HBV复制的细胞模型均基于肝癌细胞系。Huh7和HepG2细胞系在体外培养方便且易生长,尽管缺乏NTCP,但可高效支持HBV的转录、复制和病毒产生[57-58]。

2.1 稳定整合HBV基因组的细胞系 1987年,Sells团队和Chang团队分别将二倍体的HBV基因组转入不同肝癌细胞实现了病毒的复制、病毒基因的表达以及感染性病毒颗粒的形成[57-58],但病毒不能持续存在。HepG2.2.15细胞是在HepG2细胞中整合了双拷贝HBV基因组的稳定细胞株,能够稳定表达病毒基因相关产物并保证持续的HBV复制能力(表 2),已被广泛用于HBV基础生物学问题的研究,同时为早期抗病毒药物的发展提供了工具[59-60],Dandri等通过对HepG2.2.15细胞进行活性氧或DNA修复抑制剂处理,发现DNA损伤可以增加HBV整合的频率[61]。1997年,Lander等[62]利用四环素控制型CMV启动子构建了HBV 1.1倍基因组表达载体,转入HepG2细胞使其成为稳定整合HBV的HepAD38细胞株(表 2)。在HepAD38细胞中,HBV pregenomic RNA的转录和病毒基因组复制可由四环素控制。与HepG2.2.15细胞系相比,HepAD38细胞系表达可调控,在Tet-off情况下HBV病毒的产量和胞内cccDNA的积累显著高于HepG2.2.15[63]。利用该细胞系,Cui等发现TDP2 (tyrosyl-DNA-phosphodiesterase 2)的缺失并不能阻断cccDNA的形成,该发现提示TDP2对于cccDNA的形成或许并不是必需的[64]。HepDE19细胞(表 2)也是一种在Tet调控下表达HBV的稳转细胞系,该细胞系是将1.1倍体的HBV基因组转入细胞中,特殊的是整合的基因片段5′端pre-core的ATG突变成了GTG,而3′端pre-core的ATG保持完整,这种条件下HBV的E抗原(HBeAg)表达和分泌只能来源于共价闭合环状DNA (cccDNA),HBeAg的水平与胞内cccDNA水平是呈正相关的,从而为cccDNA靶向药物的高通量筛选提供了一个很好的模型[65-66]。在免疫检测中,由于HBeAg与HBcAg有154个氨基酸的同源性,多数用于HBeAg检测的抗体均与HBcAg存在一定程度的交叉反应,再加上naked HBV capsid的大量存在,使得在此种条件下采用商品化的HBeAg试剂检测到的可能不是真正意义上的HBeAg,可能无法准确反映胞内cccDNA的真实水平。为解决这一问题,Cai等[67]将HA标签(influenza hemagglutinin,HA)插入到HBeAg的precore区,在四环素调控下进行HBV的相关表达,以HA抗体为捕获抗体、HBeAb为检测抗体,获得了不影响HBV复制且无背景反应的cccDNA报告系统(HepBHAe82)(表 2)。

表 2. HBV体外复制细胞模型 Table 2. Cell models for studying HBV replication in vitro

| Cell models | Source or feature | Advantages | Disadvantages | References |

| Hepatoma cell lines(Huh7, G2) | Hepatoblastoma hepatoma | Easy handle; cheap; stable; support efficient replication of HBV | Don’t support HBV infection; has the characteristics of cancer cells | [9, 57-58] |

| HepG2.2.15 | Stable cell line integrating double-copy HBV genome in HepG2 cells | Stable and continuous expression and replication of HBV gene; produce infectious virus | Not permissive for HBV infection; low virus production; uncontrolled replication and expression of HBV; less cccDNA formation | [59-61] |

| HepAD38 | Integration of 1.1 copies of the HBV genome in HepG2 cells, with a tet-induced promoter | Controllable replication and expression of HBV gene; virus production is relatively high; cccDNA accumulation is relatively high | Don’t support HBV infection | [62-63] |

| HepDE19 | HBeAg is expressed from cccDNA, not from the integrated genome | The amount of cccDNA is positively correlated with HBeAg; large-scale drug screening platform for cccDNA | Not permissive for HBV infection; the detection of HBeAg has a high background (homology of HBcAg) | [65-66] |

| HepBHAe82 | A second-generation cccDNA reporter model based on HepDE19 with a HA tag | The amount of cccDNA is positively correlated with HBeAg; no background (or very low); high specificity | Don’t support HBV infection; the detection is relatively complicated and long | [67] |

表选项

2.2 HBV基因组的传递载体系统 由于HepG2和Huh7两种细胞的转染效率并非十分理想,研究者探索了基于病毒载体的高效递送系统以实现不同HBV毒株在肝细胞中的高效复制。1998年,Delaney等在昆虫细胞中构建制备了携带HBV复制子的重组杆状病毒,这种杆状病毒可以将具有功能性的HBV基因组导入肝癌细胞HepG2中,进而进行HBV的复制表达、感染性病毒颗粒的形成以及细胞内可检测到的cccDNA池的形成,且HBV病毒的表达水平与所感染的病毒量呈正相关[68-70](表 3)。该系统被广泛用于体外研究实验,如NA耐药突变型HBV的功能表型研究[71]以及新型抗HBV药物药效研究[72]。腺病毒载体也被应用到HBV复制子的递送中[73],Sprinzl等以腺病毒为载体将HBV 1.3倍基因组导入293细胞中制备重组腺病毒以感染HepG2细胞,不仅检测到高效的HBV复制表达,还能通过腺病毒载体上的绿色荧光蛋白报告基因表达情况来判断基因转导效率。研究表明,使用携带HBV复制子的腺病毒载体感染不同种属的肝细胞,可实现HBV在不同种属肝细胞中的复制[74-75](表 3)。另外,以慢病毒作为载体的系统也被应用于体外研究[76]。有研究表明,使用含有HBV复制能力的重组杆状病毒和腺病毒衍生载体可促进体外更多的cccDNA量的形成[69, 75]。尽管如此,基于病毒载体的HBV复制子传递系统也存在一些限制:第一,通过病毒载体的方式将HBV基因组转入细胞完全跳过了天然情况下HBV感染的入胞阶段,因此该系统不能用于HBV生活史中重要入胞阶段的研究;第二,部分对HBV感染的宿主胞内免疫应答可能会被对用于HBV传递的病毒载体的非特异性反应所掩盖[33];第三,潜在的生物安全风险是限制该系统被广泛应用的主要因素。

表 3. HBV体外复制细胞模型-传递载体系统 Table 3. Cell models for studying HBV replication in vitro-delivery vector system

| Cell models | Source or feature | Advantages | Disadvantages | References |

| Recombinant HBV baculovirus system | Produced in insect cells | Support replication and expression of HBV; formation of infectious virus particles; formation of cccDNA pools; baculovirus can’t replicate in mammalian cells | Skip the natural phase of HBV entry; some host responses to HBV infection may be masked by non-specific reactions caused by viral vectors; safety issues | [68-70] |

| Adenovirus vector system carrying HBV genome | Produced in 293 cells | Transduction efficiency can be judged by green fluorescent protein; make HBV cross-species infection possible; high level of HBV replication | [33, 73-75] |

表选项

3 讨论和展望 支持HBV感染和复制的细胞模型是HBV研究的重要工具,其快速发展推动了我们对HBV生命周期的深入认识,也加速抗HBV新药研究的进展。支持完整HBV生命周期的细胞模型使得我们能够对HBV感染和复制的各个关键环节进行针对性的干预策略设计:如针对病毒粘附与入胞、核衣壳解聚、HBV DNA的转录、RNA逆转录、RNA的稳定、衣壳的组装、病毒的分泌等。然而,现有的细胞模型并非完美,研究者还需针对下述目标努力:(1)细胞的生理状态和指标更接近正常的肝细胞;(2)来源不受限制且容易获得;(3)更加便宜且方便培养;(4)更加高效的感染以实现HBV的感染传代等。

构建可实现可视化示踪的HBV病毒感染报告系统和可量化指示胞内cccDNA水平的便捷模型对于新型抗HBV药物的高通量大规模筛选有重要意义。一方面,实现HBV感染的可视化检测有助于结合超高分辨显微成像技术和组学技术在单细胞水平研究HBV感染和致病的分子机制。另外一方面,HBV cccDNA的清除是慢性乙肝治疗的终极目标。开发针对HBV cccDNA的药物是治愈乙肝的有效策略之一。由于HBV cccDNA的形成及维持机制尚不清楚,直接的靶向药物设计缺乏清晰的理论指导,高通量化合物库的筛选成为靶向cccDNA药物开发的最优选择。然而,目前没有简便可靠的可供高通量药物筛选使用的HBV cccDNA检测方法,此类模型的研究或将成为HBV细胞模型研究的重要方向。

References

| [1] | The Polaris Observatory Collaborators. Global prevalence, treatment, and prevention of hepatitis B virus infection in 2016: a modelling study. The Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 2018, 3(6): 383-403. |

| [2] | Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, Parkin DM, Forman D, Bray F. Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. International Journal of Cancer, 2015, 136(5): E359-E386. DOI:10.1002/ijc.29210 |

| [3] | El-Serag HB. Epidemiology of viral hepatitis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology, 2012, 142(6): 1264-1273. DOI:10.1053/j.gastro.2011.12.061 |

| [4] | Singal AK, Salameh H, Kuo YF, Fontana RJ. Meta-analysis: the impact of oral anti-viral agents on the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma in chronic hepatitis B. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 2013, 38(2): 98-106. |

| [5] | Wong GL, Tse YK, Yip TC, Chan HL, Tsoi KK, Wong VW. Long-term use of oral nucleos(t)ide analogues for chronic hepatitis B does not increase cancer risk-a cohort study of 44 494 subjects. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 2017, 45(9): 1213-1224. |

| [6] | Papatheodoridis GV, Idilman R, Dalekos GN, Buti M, Chi H, van Boemmel F, Calleja JL, Sypsa V, Goulis J, Manolakopoulos S, Loglio A, Siakavellas S, Kesk?n O, Gatselis N, Hansen BE, Lehretz M, de la Revilla J, Savvidou S, Kourikou A, Vlachogiannakos I, Galanis K, Yurdaydin C, Berg T, Colombo M, Esteban R, Janssen HLA, Lampertico P. The risk of hepatocellular carcinoma decreases after the first 5 years of entecavir or tenofovir in Caucasians with chronic hepatitis B. Hepatology, 2017, 66(5): 1444-1453. DOI:10.1002/hep.29320 |

| [7] | Xia YC, Carpentier A, Cheng XM, Block PD, Zhao Y, Zhang ZS, Protzer U, Liang TJ. Human stem cell-derived hepatocytes as a model for hepatitis B virus infection, spreading and virus-host interactions. Journal of Hepatology, 2017, 66(3): 494-503. DOI:10.1016/j.jhep.2016.10.009 |

| [8] | Zeyen L, Prange R. Host cell rab gtpases in hepatitis B virus infection. Frontiers in Cell and Developmental Biology, 2018, 6: 154. DOI:10.3389/fcell.2018.00154 |

| [9] | Yan H, Zhong GC, Xu GW, He WH, Jing ZY, Gao ZC, Huang Y, Qi YH, Peng B, Wang HM, Fu LR, Song M, Chen P, Gao WQ, Ren BJ, Sun YY, Cai T, Feng XF, Sui JH, Li WH. Sodium taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide is a functional receptor for human hepatitis B and D virus. eLife, 2012, 1: e00049. DOI:10.7554/eLife.00049 |

| [10] | Nishitsuji H, Harada K, Ujino S, Zhang J, Kohara M, Sugiyama M, Mizokami M, Shimotohno K. Investigating the hepatitis B virus life cycle using engineered reporter hepatitis B viruses. Cancer Science, 2018, 109(1): 241-249. |

| [11] | Takahashi N, Hayashi K, Nakagawa Y, Furutani Y, Toguchi M, Shiozaki-Sato Y, Sudoh M, Kojima S, Kakeya H. Development of an anti-hepatitis B virus (HBV) agent through the structure-activity relationship of the interferon-like small compound CDM-3008. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry, 2019, 27(3): 470-478. |

| [12] | Arends JE, Lieveld FI, Ahmad S, Ustianowski A. New viral and immunological targets for hepatitis B treatment and cure: a review. Infectious Diseases and Therapy, 2017, 6(4): 461-476. DOI:10.1007/s40121-017-0173-y |

| [13] | Wu GY, Liu B, Zhang YJ, Li J, Arzumanyan A, Clayton MM, Schinazi RF, Wang ZH, Goldmann S, Ren QY, Zhang FH, Feitelson MA. Preclinical characterization of GLS4, an inhibitor of hepatitis B virus core particle assembly. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 2013, 57(11): 5344-5354. DOI:10.1128/AAC.01091-13 |

| [14] | Gripon P, Diot C, Thézé N, Fourel I, Loreal O, Brechot C, Guguen-Guillouzo C. Hepatitis B virus infection of adult human hepatocytes cultured in the presence of dimethyl sulfoxide. Journal of Virology, 1988, 62(11): 4136-4143. |

| [15] | Zeisel MB, Lucifora J, Mason WS, Sureau C, Beck J, Levrero M, Kann M, Knolle PA, Benkirane M, Durantel D, Michel ML, Autran B, Cosset FL, Strick-Marchand H, Trépo C, Kao JH, Carrat F, Lacombe K, Schinazi RF, Barré-Sinoussi F, Delfraissy JF, Zoulim F. Towards an HBV cure: state-of-the-art and unresolved questions-report of the ANRS workshop on HBV cure. Gut, 2015, 64(8): 1314-1326. DOI:10.1136/gutjnl-2014-308943 |

| [16] | Allweiss L, Dandri M. Experimental in vitro and in vivo models for the study of human hepatitis B virus infection. Journal of Hepatology, 2016, 64(1 Suppl): S17-S31. |

| [17] | Khetani SR, Bhatia SN. Microscale culture of human liver cells for drug development. Nature Biotechnology, 2008, 26(1): 120-126. |

| [18] | Shlomai A, Schwartz RE, Ramanan V, Bhatta A, de Jong YP, Bhatia SN, Rice CM. Modeling host interactions with hepatitis B virus using primary and induced pluripotent stem cell-derived hepatocellular systems. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2014, 111(33): 12193-12198. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1412631111 |

| [19] | Ramanan V, Scull MA, Sheahan TP, Rice CM, Bhatia SN. New methods in tissue engineering: improved models for viral infection. Annual Review of Virology, 2014, 1: 475-499. DOI:10.1146/annurev-virology-031413-085437 |

| [20] | Walter E, Keist R, Nieder?st B, Pult I, Blum HE. Hepatitis B virus infection of tupaia hepatocytes in vitro and in vivo. Hepatology, 1996, 24(1): 1-5. |

| [21] | K?ck J, Baumert TF, Delaney IV WE, Blum HE, von Weizs?cker F. Inhibitory effect of adefovir and lamivudine on the initiation of hepatitis B virus infection in primary tupaia hepatocytes. Hepatology, 2003, 38(6): 1410-1418. |

| [22] | Baumert TF, Yang C, Schürmann P, K?ck J, Ziegler C, Grüllich C, Nassal M, Liang TJ, Blum HE, von Weizs?cker F. Hepatitis B virus mutations associated with fulminant hepatitis induce apoptosis in primary Tupaia hepatocytes. Hepatology, 2005, 41(2): 247-256. DOI:10.1002/hep.20553 |

| [23] | Yoneda M, Hyun J, Jakubski S, Saito S, Nakajima A, Schiff ER, Thomas E. Hepatitis B Virus and DNA stimulation trigger a rapid innate immune response through NF-κB. The Journal of Immunology, 2016, 197(2): 630-643. DOI:10.4049/jimmunol.1502677 |

| [24] | Luangsay S, Gruffaz M, Isorce N, Testoni B, Michelet M, Faure-Dupuy S, Maadadi S, Ait-Goughoulte M, Parent R, Rivoire M, Javanbakht H, Lucifora J, Durantel D, Zoulim F. Early inhibition of hepatocyte innate responses by hepatitis B virus. Journal of Hepatology, 2015, 63(6): 1314-1322. DOI:10.1016/j.jhep.2015.07.014 |

| [25] | Gripon P, Rumin S, Urban S, Le Seyec J, Glaise D, Cannie I, Guyomard C, Lucas J, Trepo C, Guguen-Guillouzo C. Infection of a human hepatoma cell line by hepatitis B virus. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 2002, 99(24): 15655-15660. DOI:10.1073/pnas.232137699 |

| [26] | Lucifora J, Esser K, Protzer U. Ezetimibe blocks hepatitis B virus infection after virus uptake into hepatocytes. Antiviral Research, 2013, 97(2): 195-197. DOI:10.1016/j.antiviral.2012.12.008 |

| [27] | Hantz O, Parent R, Durantel D, Gripon P, Guguen-Guillouzo C, Zoulim F. Persistence of the hepatitis B virus covalently closed circular DNA in HepaRG human hepatocyte-like cells. Journal of General Virology, 2009, 90: 127-135. DOI:10.1099/vir.0.004861-0 |

| [28] | Yuan LZ, Liu X, Zhang L, Zhang YL, Chen Y, Li XL, Wu K, Cao JL, Hou WH, Que YQ, Zhang J, Zhu H, Yuan Q, Tang QY, Cheng T, Xia NS. Optimized HepaRG is a suitable cell source to generate the human liver chimeric mouse model for the chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Emerging Microbes & Infections, 2018, 7: 144. |

| [29] | Schulze A, Gripon P, Urban S. Hepatitis B virus infection initiates with a large surface protein-dependent binding to heparan sulfate proteoglycans. Hepatology, 2007, 46(6): 1759-1768. DOI:10.1002/hep.21896 |

| [30] | Sureau C, Salisse J. A conformational heparan sulfate binding site essential to infectivity overlaps with the conserved hepatitis B virus a-determinant. Hepatology, 2013, 57(3): 985-994. DOI:10.1002/hep.26125 |

| [31] | Ni Y, Lempp FA, Mehrle S, Nkongolo S, Kaufman C, F?lth M, Stindt J, K?niger C, Nassal M, Kubitz R, Sültmann H, Urban S. Hepatitis B and D viruses exploit sodium taurocholate co-transporting polypeptide for species-specific entry into hepatocytes. Gastroenterology, 2014, 146(4): 1070-1083. DOI:10.1053/j.gastro.2013.12.024 |

| [32] | Macovei A, Radulescu C, Lazar C, Petrescu S, Durantel D, Dwek RA, Zitzmann N, Nichita NB. Hepatitis B virus requires intact caveolin-1 function for productive infection in HepaRG cells. Journal of Virology, 2010, 84(1): 243-253. DOI:10.1128/JVI.01207-09 |

| [33] | Lucifora J, Durantel D, Testoni B, Hantz O, Levrero M, Zoulim F. Control of hepatitis B virus replication by innate response of HepaRG cells. Hepatology, 2010, 51(1): 63-72. DOI:10.1002/hep.23230 |

| [34] | Cui XJ, Luckenbaugh L, Bruss V, Hu JM. Alteration of mature nucleocapsid and enhancement of covalently closed circular DNA formation by hepatitis B virus core mutants defective in complete-virion formation. Journal of Virology, 2015, 89(19): 10064-10072. DOI:10.1128/JVI.01481-15 |

| [35] | Li JS, Zong L, Sureau C, Barker L, Wands JR, Tong SP. Unusual features of sodium taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide as a hepatitis B virus receptor. Journal of Virology, 2016, 90(18): 8302-8313. DOI:10.1128/JVI.01153-16 |

| [36] | Qiao LH, Sui JH, Luo GX. Robust human and murine hepatocyte culture models of hepatitis B virus infection and replication. Journal of Virology, 2018, 92(23): e01255-18. |

| [37] | Yan H, Peng B, He WH, Zhong GC, Qi YH, Ren BJ, Gao ZC, Jing ZY, Song M, Xu GW, Sui JH, Li WH. Molecular determinants of hepatitis B and D virus entry restriction in mouse sodium taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide. Journal of Virology, 2013, 87(14): 7977-7991. DOI:10.1128/JVI.03540-12 |

| [38] | Winer BY, Ploss A. Determinants of hepatitis B and delta virus host tropism. Current Opinion in Virology, 2015, 13: 109-116. DOI:10.1016/j.coviro.2015.06.004 |

| [39] | Li HJ, Zhuang QY, Wang YZ, Zhang TY, Zhao JH, Zhang YL, Zhang JF, Lin Y, Yuan Q, Xia NS, Han JH. HBV life cycle is restricted in mouse hepatocytes expressing human NTCP. Cellular and Molecular Immunology, 2014, 11(2): 175-183. DOI:10.1038/cmi.2013.66 |

| [40] | Lempp FA, Mutz P, Lipps C, Wirth D, Bartenschlager R, Urban S. Evidence that hepatitis B virus replication in mouse cells is limited by the lack of a host cell dependency factor. Journal of Hepatology, 2016, 64(3): 556-564. DOI:10.1016/j.jhep.2015.10.030 |

| [41] | Cui XJ, Guo JT, Hu JM. Hepatitis B virus covalently closed circular DNA formation in immortalized mouse hepatocytes associated with nucleocapsid destabilization. Journal of Virology, 2015, 89(17): 9021-9028. DOI:10.1128/JVI.01261-15 |

| [42] | Lempp FA, Qu BQ, Wang YX, Urban S. Hepatitis B virus infection of a mouse hepatic cell line reconstituted with human sodium taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide. Journal of Virology, 2016, 90(9): 4827-4831. DOI:10.1128/JVI.02832-15 |

| [43] | Ko C, Lee S, Windisch MP, Ryu WS. DDX3 DEAD-box RNA helicase is a host factor that restricts hepatitis B virus replication at the transcriptional level. Journal of Virology, 2014, 88(23): 13689-13698. DOI:10.1128/JVI.02035-14 |

| [44] | Verrier ER, Colpitts CC, Bach C, Heydmann L, Weiss A, Renaud M, Durand SC, Habersetzer F, Durantel D, Abou-Jaoudé G, López Ledesma MM, Felmlee DJ, Soumillon M, Croonenborghs T, Pochet N, Nassal M, Schuster C, Brino L, Sureau C, Zeisel MB, Baumert TF. A targeted functional RNA interference screen uncovers glypican 5 as an entry factor for hepatitis B and D viruses. Hepatology, 2016, 63(1): 35-48. DOI:10.1002/hep.28013 |

| [45] | Nkongolo S, Ni Y, Lempp FA, Kaufman C, Lindner T, Esser-Nobis K, Lohmann V, Mier W, Mehrle S, Urban S. Cyclosporin A inhibits hepatitis B and hepatitis D virus entry by cyclophilin-independent interference with the NTCP receptor. Journal of Hepatology, 2014, 60(4): 723-731. DOI:10.1016/j.jhep.2013.11.022 |

| [46] | Iwamoto M, Watashi K, Tsukuda S, Aly HH, Fukasawa M, Fujimoto A, Suzuki R, Aizaki H, Ito T, Koiwai O, Kusuhara H, Wakita T. Evaluation and identification of hepatitis B virus entry inhibitors using HepG2 cells overexpressing a membrane transporter NTCP. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 2014, 443(3): 808-813. DOI:10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.12.052 |

| [47] | Bouezzedine F, Fardel O, Gripon P. Interleukin 6 inhibits HBV entry through NTCP down regulation. Virology, 2015, 481: 34-42. DOI:10.1016/j.virol.2015.02.026 |

| [48] | Saso W, Tsukuda S, Ohashi H, Fukano K, Morishita R, Matsunaga S, Ohki M, Ryo A, Park SY, Suzuki R, Aizaki H, Muramatsu M, Sureau C, Wakita T, Matano T, Watashi K. A new strategy to identify hepatitis B virus entry inhibitors by AlphaScreen technology targeting the envelope-receptor interaction. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 2018, 501(2): 374-379. DOI:10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.04.187 |

| [49] | Kaneko M, Watashi K, Kamisuki S, Matsunaga H, Iwamoto M, Kawai F, Ohashi H, Tsukuda S, Shimura S, Suzuki R, Aizaki H, Sugiyama M, Park SY, Ito T, Ohtani N, Sugawara F, Tanaka Y, Mizokami M, Sureau C, Wakita T. A novel tricyclic polyketide, vanitaracin A, specifically inhibits the entry of hepatitis B and D viruses by targeting sodium taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide. Journal of Virology, 2015, 89(23): 11945-11953. DOI:10.1128/JVI.01855-15 |

| [50] | Ko C, Park WJ, Park S, Kim S, Windisch MP, Ryu WS. The FDA-approved drug irbesartan inhibits HBV-infection in HepG2 cells stably expressing sodium taurocholate co-transporting polypeptide. Antiviral Therapy, 2015, 20(8): 835-842. DOI:10.3851/IMP2965 |

| [51] | Nishitsuji H, Ujino S, Shimizu Y, Harada K, Zhang J, Sugiyama M, Mizokami M, Shimotohno K. Novel reporter system to monitor early stages of the hepatitis B virus life cycle. Cancer Science, 2015, 106(11): 1616-1624. DOI:10.1111/cas.12799 |

| [52] | Harada K, Nishitsuji H, Ujino S, Shimotohno K. Identification of KX2-391 as an inhibitor of HBV transcription by a recombinant HBV-based screening assay. Antiviral Research, 2017, 144: 138-146. DOI:10.1016/j.antiviral.2017.06.005 |

| [53] | Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell, 2006, 126(4): 663-676. DOI:10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024 |

| [54] | Schwartz RE, Fleming HE, Khetani SR, Bhatia SN. Pluripotent stem cell-derived hepatocyte-like cells. Biotechnology Advances, 2014, 32(2): 504-513. DOI:10.1016/j.biotechadv.2014.01.003 |

| [55] | Yuan LZ, Liu X, Zhang L, Li XL, Zhang YL, Wu K, Chen Y, Cao JL, Hou WH, Zhang J, Zhu H, Yuan Q, Tang QY, Cheng T, Xia NS. A chimeric humanized mouse model by engrafting the human induced pluripotent stem cell-derived hepatocyte-like cell for the chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Frontiers in Microbiology, 2018, 9: 908. DOI:10.3389/fmicb.2018.00908 |

| [56] | Huang PY, Zhang LD, Gao YM, He ZY, Yao D, Wu ZT, Cen J, Chen XT, Liu CC, Hu YP, Lai DM, Hu ZL, Chen L, Zhang Y, Cheng X, Ma XJ, Pan GY, Wang X, Hui LJ. Direct reprogramming of human fibroblasts to functional and expandable hepatocytes. Cell Stem Cell, 2014, 14(3): 370-384. DOI:10.1016/j.stem.2014.01.003 |

| [57] | Chang CM, Jeng KS, Hu CP, Lo SJ, Su TS, Ting LP, Chou CK, Han SH, Pfaff E, Salfeld J. Production of hepatitis B virus in vitro by transient expression of cloned HBV DNA in a hepatoma cell line. The EMBO Journal, 1987, 6(3): 675-680. DOI:10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb04807.x |

| [58] | Sells MA, Chen ML, Acs G. Production of hepatitis B virus particles in Hep G2 cells transfected with cloned hepatitis B virus DNA. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 1987, 84(4): 1005-1009. DOI:10.1073/pnas.84.4.1005 |

| [59] | Li GQ, Xu WZ, Wang JX, Deng WW, Li D, Gu HX. Combination of small interfering RNA and lamivudine on inhibition of human B virus replication in HepG2.2.15 cells. World Journal of Gastroenterology, 2007, 13(16): 2324-2327. DOI:10.3748/wjg.v13.i16.2324 |

| [60] | Ding XR, Yang J, Sun DC, Lou SK, Wang SQ. Whole genome expression profiling of hepatitis B virus-transfected cell line reveals the potential targets of anti-HBV drugs. The Pharmacogenomics Journal, 2008, 8(1): 61-70. |

| [61] | Dandri M, Burda MR, Bürkle A, Zuckerman DM, Will H, Rogler CE, Greten H, Petersen J. Increase in de novo HBV DNA integrations in response to oxidative DNA damage or inhibition of poly(ADP-ribosyl)ation. Hepatology, 2002, 35(1): 217-223. DOI:10.1053/jhep.2002.30203 |

| [62] | Ladner SK, Otto MJ, Barker CS, Zaifert K, Wang GH, Guo JT, Seeger C, King RW. Inducible expression of human hepatitis B virus (HBV) in stably transfected hepatoblastoma cells: a novel system for screening potential inhibitors of HBV replication. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 1997, 41(8): 1715-1720. DOI:10.1128/AAC.41.8.1715 |

| [63] | Sun DX, Nassal M. Stable HepG2- and Huh7-based human hepatoma cell lines for efficient regulated expression of infectious hepatitis B virus. Journal of Hepatology, 2006, 45(5): 636-645. DOI:10.1016/j.jhep.2006.05.019 |

| [64] | Cui XJ, McAllister R, Boregowda R, Sohn JA, Cortes Ledesma F, Caldecott KW, Seeger C, Hu JM. Does tyrosyl DNA phosphodiesterase-2 play a role in hepatitis B virus genome repair?. PLoS One, 2015, 10(6): e0128401. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0128401 |

| [65] | Cai DW, Mills C, Yu WQ, Yan R, Aldrich CE, Saputelli JR, Mason WS, Xu XD, Guo JT, Block TM, Cuconati A, Guo HT. Identification of disubstituted sulfonamide compounds as specific inhibitors of hepatitis B virus covalently closed circular DNA formation. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 2012, 56(8): 4277-4288. DOI:10.1128/AAC.00473-12 |

| [66] | Guo HT, Jiang D, Zhou TL, Cuconati A, Block TM, Guo JT. Characterization of the intracellular deproteinized relaxed circular DNA of hepatitis B virus: an intermediate of covalently closed circular DNA formation. Journal of Virology, 2007, 81(22): 12472-12484. DOI:10.1128/JVI.01123-07 |

| [67] | Cai DW, Wang XH, Yan R, Mao RC, Liu YJ, Ji CH, Cuconati A, Guo HT. Establishment of an inducible HBV stable cell line that expresses cccDNA-dependent epitope-tagged HBeAg for screening of cccDNA modulators. Antiviral Research, 2016, 132: 26-37. DOI:10.1016/j.antiviral.2016.05.005 |

| [68] | Delaney IV WE, Isom HC. Hepatitis B virus replication in human HepG2 cells mediated by hepatitis B virus recombinant baculovirus. Hepatology, 1998, 28(4): 1134-1146. DOI:10.1002/hep.510280432 |

| [69] | Lucifora J, Durantel D, Belloni L, Barraud L, Villet S, Vincent IE, Margeridon-Thermet S, Hantz O, Kay A, Levrero M, Zoulim F. Initiation of hepatitis B virus genome replication and production of infectious virus following delivery in HepG2 cells by novel recombinant baculovirus vector. Journal of General Virology, 2008, 89: 1819-1828. DOI:10.1099/vir.0.83659-0 |

| [70] | Isom HC, Abdelhamed AM, Bilello JP, Miller TG. Baculovirus-mediated gene transfer for the study of hepatitis B virus. Methods in Molecular Medicine, 2004, 96: 219-237. |

| [71] | Chen RYM, Edwards R, Shaw T, Colledge D, Delaney IV WE, Isom H, Bowden S, Desmond P, Locarnini SA. Effect of the G1896A precore mutation on drug sensitivity and replication yield of lamivudine-resistant HBV in vitro. Hepatology, 2003, 37(1): 27-35. DOI:10.1053/jhep.2003.50012 |

| [72] | Delaney IV WE, Miller TG, Isom HC. Use of the hepatitis B virus recombinant baculovirus-HepG2 system to study the effects of (-)-beta-2', 3'-dideoxy-3'-thiacytidine on replication of hepatitis B virus and accumulation of covalently closed circular DNA. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 1999, 43(8): 2017-2026. DOI:10.1128/AAC.43.8.2017 |

| [73] | Wilson JM. Adenoviruses as gene-delivery vehicles. The New England Journal of Medicine, 1996, 334(18): 1185-1187. DOI:10.1056/NEJM199605023341809 |

| [74] | Sprinzl MF, Oberwinkler H, Schaller H, Protzer U. Transfer of hepatitis B virus genome by adenovirus vectors into cultured cells and mice: crossing the species barrier. Journal of Virology, 2001, 75(11): 5108-5118. DOI:10.1128/JVI.75.11.5108-5118.2001 |

| [75] | Ren ST, Nassal M. Hepatitis B virus (HBV) virion and covalently closed circular DNA formation in primary Tupaia hepatocytes and human hepatoma cell lines upon HBV genome transduction with replication-defective adenovirus vectors. Journal of Virology, 2001, 75(3): 1104-1116. DOI:10.1128/JVI.75.3.1104-1116.2001 |

| [76] | Cohen D, Adamovich Y, Reuven N, Shaul Y. Hepatitis B virus activates deoxynucleotide synthesis in nondividing hepatocytes by targeting the R2 gene. Hepatology, 2010, 51(5): 1538-1546. DOI:10.1002/hep.23519 |