,1,2, 艾莉达1,2, Thomas A. STIDHAM1,2,3, 王敏1,2, 邓涛1,2,3

,1,2, 艾莉达1,2, Thomas A. STIDHAM1,2,3, 王敏1,2, 邓涛1,2,3Exceptional preservation of an extinct ostrich from the Late Miocene Linxia Basin of China

LI Zhi-Heng ,1,2, Alida M. BAILLEUL1,2, Thomas A. STIDHAM1,2,3, WANG Min1,2, DENG Tao1,2,3

,1,2, Alida M. BAILLEUL1,2, Thomas A. STIDHAM1,2,3, WANG Min1,2, DENG Tao1,2,3通讯作者: lizhiheng@ivpp.ac.cn

收稿日期:2020-12-25

| 基金资助: |

Corresponding authors: lizhiheng@ivpp.ac.cn

Received:2020-12-25

摘要

报道了来自西北地区中新世晚期临夏盆地的一件鸵鸟化石,该标本包括鸵鸟的部分颈椎以及气管,由于缺乏物种级别的鉴定特征,被暂定为鸵鸟(Struthio sp.)。新标本还保留了平齿三趾马(Hipparion platyodus)的部分头骨。利用多种分析测试方法,对该鸵鸟骨骼的微观特征进行了详细研究,以探讨临夏鸵鸟的埋藏条件和古气候背景。在鸵鸟化石的一个脱矿化的骨碎片中发现了软组织(内源性血管和红细胞的化石残留)。同时光学显微镜和扫描电镜成像显示,化石组织切片中存在显著的细菌改变(骨侵蚀现象)。这是中新世临夏盆地脊椎动物遗体中软组织的首次报道。通过相关的地质和沉积学证据与新的古生物数据相结合,认为季风气候可能是造成鸟类化石早期埋葬期间微生物侵蚀的原因,接下来延续了8 Ma左右的盆地剧烈的干旱化作用,导致了微生物活动的停止,并进一步导致了成岩作用后期孔隙方解石的沉淀。这项工作显示出跨学科(包括形态学、沉积学、地球化学和软组织分析)研究可以更好地揭示中国西北临夏盆地柳树组的中新世晚期的动物群更替、气候和分子保存。

关键词:

Abstract

Here we report a new avian fossil from the Late Miocene Linxia Basin, Northwest China, with exceptional soft-tissue preservation. This specimen preserves parts of cervical vertebrae and tracheal rings that are typically ostrich-like, but cannot be diagnosed at the species level. Therefore, the fossil is referred to Struthio sp. The new specimen was preserved in association with a partial skull of Hipparion platyodus. To explore the soft tissue preservation in a fossil deposited in a terrestrial setting, we applied a combination of analytic methods to investigate the microscopic features of the fossilized avian bone. Bacterial alterations (bone bioerosion) were revealed by light microscopy and petrographic sections under SEM imaging. Soft-tissues (fossilized remnants of endogenous blood vessels and red blood cells) were preserved in one demineralized bone fragment and also observed in the in-situ ground-section. These are the first records of soft-tissue preservation in vertebrate remains from the Late Miocene Linxia Basin. Associated geological and sedimentological evidence combined with our new data provide insights into the postmortem taphonomic conditions of this ostrich specimen. A seasonal monsoon might have facilitated the microbial erosion penecontemporaneous with the burial of the specimen. This study encourages interdisciplinary research involving morphology, sedimentology, geochemistry, and histological soft-tissue analyses to better understand the Late Miocene faunal turnovers, climates, and fossil preservation in the Liushu Formation in northwestern China.

Keywords:

PDF (4397KB)元数据多维度评价相关文章导出EndNote|Ris|Bibtex收藏本文

本文引用格式

李志恒, 艾莉达, Thomas A. STIDHAM, 王敏, 邓涛. 临夏盆地晚中新世鸵鸟化石的特异保存. 古脊椎动物学报[J], 2021, 59(3): 229-244 DOI:10.19615/j.cnki.1000-3118.210309

LI Zhi-Heng, Alida M. BAILLEUL, Thomas A. STIDHAM, WANG Min, DENG Tao.

1 Introduction

The Late Miocene is a key period of Cenozoic climatic change that saw overall global cooling, increased aridification in Central Asia, and intensification of the seasonal monsoon related to the continued uplift of the Himalayas and the Tibetan Plateau as a whole (An et al., 2001; Qiang et al., 2011). The Miocene sedimentary deposits of the Linxia Basin in Gansu Province in Northwestern China provide a unique setting to investigate faunal shifts across a spectrum of changing paleoclimates (Deng, 2005; Fan et al., 2007; Wang et al., 2010a; Zhang et al., 2019). Located at the geographic edge of the Tibetan Plateau, the thick geological sequences of the Linxia Basin yield abundant data for studies of both the paleontology and paleoclimate of this high altitude Neogene terrestrial ecosystem (Ma et al., 1998; Deng, 2009; Deng et al., 2013). The Late Miocene deposits comprising the Liushu Formation are composed largely of yellow and reddish-brown siltstones, mudstones, and potential paleosol beds, and the vertebrate fossil-bearing horizons are concentrated within lenticular bodies within the siltstones (Deng et al., 2013; An, 2014). The Liushu Formation is exposed widely across the basin, and maintains an average thickness of ~90 m (Fang et al., 2003; Deng et al., 2013). Previous workers have interpreted the depositional facies as fluvial-lacustrine-eolian complexes, and they attribute the highly variable formation thickness across the basin (seen in different stratigraphic sections from north to south) as the result of tectonic uplift and differential erosion (Deng et al., 2004; Zhang et al., 2019). The Liushu Formation is thicker along the southern margin of the basin where there is a large proportion of coarse sediments (An, 2014). The stratigraphically lower Hujialiang Formation (Middle Miocene) is composed mainly of sandstones and conglomerates representing fluvial deposits which fine upwards towards the Liushu Formation and its typical ‘red clay layers’ ( Deng et al., 2004).The fossiliferous beds within the Liushu Formation have been divided into four units based on the extremely abundant fossil mammals (Deng et al., 2004). Numerous large-bodied mammalian fossils are known from dozens of localities, and the fauna includes typical members of the Hipparion fauna, such as the bovid Hezhengia, the hyena Dinocrocuta, the antelope Gazella, and the rhinoceros Chilotherium (Deng, 2005; Deng et al., 2013). More recently, studies of the less common avian fauna have documented a diversity of taxonomic groups known from the Linxia Basin at various localities, including pheasants (Galliformes), vultures (Accitripidiformes), falcons (Falconidae), extinct crane relatives (Eogruidae), sandgrouse (Pteroclididae), an owl (Strigidae), and ostriches (Struthionidae) (Zhang et al., 2012; Li et al., 2014, 2016, 2018; Musser et al., 2019). Based on an incomplete pelvic region (partial pelvis and synsacrum), Hou et al. (2005) described the extinct Linxia ostrich ( Struthio linxiaensis) as the first documented avian species from the basin, and additional ostrich material from multiple localities, that will be published elsewhere, has been found since its initial identification (unpublished observation).

As part of this documentation of new ostrich fossil specimens, we report the first material of cervical vertebrae and associated ossified tracheal rings that are referred to Struthio from the Linxia Basin. Exceptional preservation is seen in some avian fossils from the Liushu Formation (Li et al., 2018), and we strive to understand the mechanisms resulting in this remarkable preservation in the terrestrial environment of the Linxia Basin. Furthermore, we aim to explore the potential environmental and diagenetic factors that led to this type and quality of preservation. Analyses of this ostrich specimen at the biological tissue level, using standard paleohistological examination combined with SEM imaging, as well as demineralization, provide unique results. For the first time, our research reveals the preservation of soft tissues (fossilized, endogenous blood vessels, and red blood cells) in Liushu Formation fossils, and indicates the further potential for exceptional preservation of other organic compounds within its fossilized bony materials. In this first histological study of a Liushu Formation avian fossil, we document bacterial alterations for the first time in the cervical vertebrae, and confirm indirect evidence for potential microbial activity suggested by the previous biomarker analyses (Wang et al., 2010b, 2012).

Through histological study of the preserved soft tissue residues, we propose a mechanism for the soft-tissue preservation based on the new microscopic data, and reconstruct the depositional and related diagenetic history of our fossil material (Wang and Deng, 2005; Zheng et al., 2006; Wang et al., 2010b; Zhang and Sun, 2011). Analysis of the microscopic features of the bone tissues provides novel insight into its localized, postmortem burial environments. The data also provides some preliminary, although more wide-ranging insights about past climate change and conditions in the Linxia Basin. This study encourages more interdisciplinary research that combines vertebrate morphology with other fields including bone histology, soft-tissue analyses, and molecular paleontology in a well-constrained chronostratigraphic framework (Fang et al., 2003; Wang et al., 2010a).

Institutional abbreviation IVPP, Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing.

2 Materials and methods

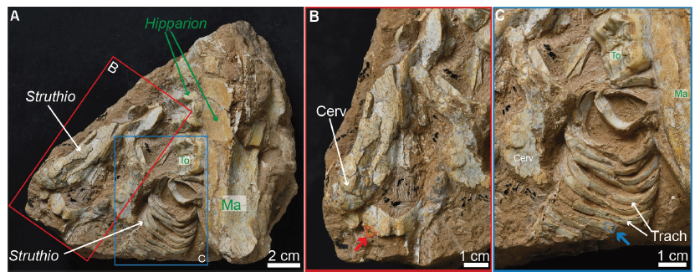

The fossil specimen (IVPP V 25336) includes cervical vertebrae and associated ossified tracheal rings, and the fossil block of reddish-tan fine-grained sediments was discovered at the town of Nalesi, Dongxiang County (Shuang-gong-bei village). The fossiliferous block is most likely from the middle part of the Liushu Formation which ranges in age 7-10 Ma based on mammalian fossils (Bahean Chinese Land Mammal Age) found from the same locality (Qiu et al., 2013). The sediment block also contains part of a right maxilla of a juvenile three-toed horse Hipparion platyodus (based on its strong enamel plications and lingually flat protocones of three deciduous premolars) preserved next to the ostrich cervical vertebrae and partially articulated tracheal rings. Other small fragments of bones and teeth are present in the block, and they might represent additional taxa and individuals. This kind of fossil assemblage with broken bones and partially articulated materials of multiple taxa are relatively common in the formation. TheHipparion specimen further indicates this fossil assemblage belongs to the Yangjiashan fauna, with an age of ~8 Ma.In total, two samples were extracted from the fossil bones. One sample was taken from an ossified tracheal ring and the other sample comes from a cervical vertebra (Fig. 1). Each sample was then broken into two pieces; with one used for petrographic sectioning and SEM imaging, and the other for demineralization and soft-tissue characterization.

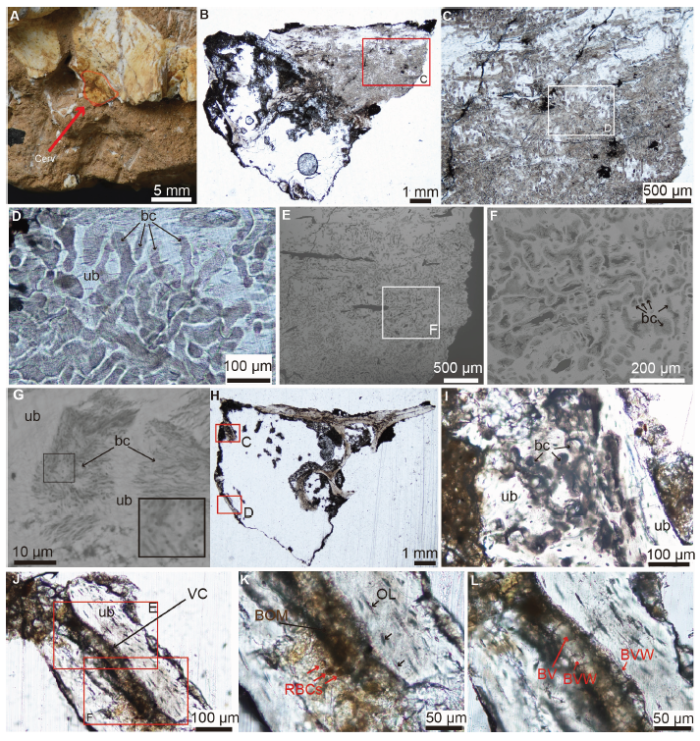

Fig. 1

新窗口打开|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT

新窗口打开|下载原图ZIP|生成PPTFig. 1Photographs of the fossil block (IVPP V 25336) from the Liushu Formation in Linxia Basin

A. the block contains an assemblage of two species, with Struthio sp. (ostrich) cervical bones on the left side and a partial right maxilla of Hipparion platyodus on the right; B. close-up on the ostrich cervical vertebrae with a red arrow indicating the location of the fragment extracted; C. close-up of the ostrich tracheal rings, with a blue arrow showing where the fragment was extracted

Abbreviations: Cerv. cervical vertebra; Ma. maxilla; To. tooth; Trach. tracheal rings

Petrographic ground-sections The fragments were embedded in EXAKT Technovit 7200 (Norderstedt, Germany) one-component resin, and cured for 24 hours. The resulting blocks were mounted onto glass slides with EXAKT Technovit 4000. The sections were cut using an EXAKT 300CP accurate circular saw, and then ground and polished using the EXAKT 400CS grinding system (Norderstedt, Germany) until the desired optical contrast was reached around 50-70 μm thickness. Sections were observed under transmitted and polarized light using a Nikon eclipse LV100NPOL microscope, and photographed with a DS-Fi3 camera along with the build-in NIS-Element v4.60 software. We used the Photomerge tool to reconstruct the entire sections.

SEM (Scanning Electronic Microscopy) SEM images were taken at the Chinese Academy of Geological Sciences (Beijing) using FEI Quanta 450 (FEG) at 20 kv. Both BSE and SE modes (back-scattered electrons and secondary electrons) were applied to the ground-sections. These methods have been used in previous studies of microscopic bony features and microscopic focal destructions (abbreviated as MFD) (Hackett, 1981; Fernández-Jalvo et al., 2010; Pesquero et al., 2010).

Demineralization The two fragments were placed in separate and sterile petri dishes. Solutions of EDTA (Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid) (500 mM EDTA; pH 8.0) were pipetted with sterile pipettes into the sterile dishes and changed almost every day for one week. Drops of the demineralized solutions with demineralized fossil material were put onto glass slides, cover-slipped, and observed under transmitted light under a petrographic microscope. Soft-tissue structures were already visible after 24-48 hours in the demineralizing solution.

3 Results

3.1 Bone morphology and histology

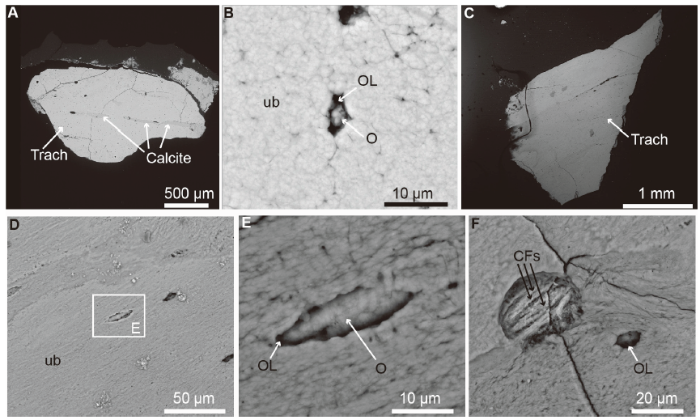

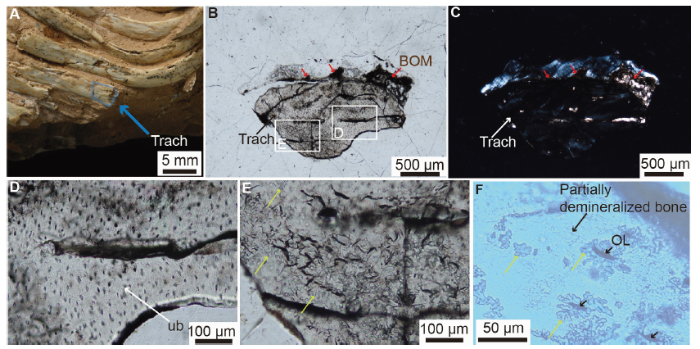

The ostrich cervical material comprises portions of at least two articulated cervical vertebrae (Fig. 1). The most complete vertebra is exposed in dorsal view, and has a maximum craniocaudal length of about 88 mm with a mediolateral width near 60 mm. Diagnostic features that support the new specimen asStruthio include the presence of large prezygapophyses, a dorsal tubercle on the postzygapophyses, and a slightly raised neural spine. Exposed cranial to that vertebra is the caudal edge of a neural arch of another cervical, and on the left side of the more complete vertebra and adjacent to the tracheal rings is another fragment of bone, which could represent a third cervical. The aspect ratio of the preserved cervical (maximum length/width < 2) indicates that it derives from the caudal part of the neck ( Cobley et al., 2013). The majority of the tracheal rings are positioned to the left side of the cervicals, with part of one ring under the caudal end of the more complete vertebra. The other smaller bony fragments could derive from the vertebrae, tracheal rings, or an adjacent Hipparion individual. The left lateral position of the segment of the trachea is likely not the life position based on comparison with the living species, which tends to have a midline trachea or right lateral displacement in the caudal portion of the neck. The tracheal rings are quite wide with a diameter of approximately 3.5 cm, and the craniocaudal length of the trachea segment (comprised of a minimum of 12 tracheal rings) is more than 6 cm with individual ring lengths of ~3.5-4.0 mm. The rings bear a gentle concavity on the ventral side (Fig. 1). The external and visible internal surfaces of the tracheal rings are relatively smooth with some surficial linear features, short shallow grooves, and foramina. The intense ossification of the tracheal rings is remarkably different from that of extant ostrich individuals, in which most rings are cartilaginous in juveniles, with only a few ossified rings in relatively old individuals (Mclelland, 1989; Atalgin et al., 2018).SEM imagery reveals that the bone matrix of the tracheal ring is extremely well-preserved (see two different petrographic slides in Figs. 2, 3). Some fibers that are morphologically consistent with collagen fibers are visible (Fig. 2B, F). Some intralacunar contents in the osteocyte lacunae are likely to be fossilized remnants of the original osteocytes (Fig. 2B, E). The only clear diagenetic alteration visible in the sample is in the dendritic structures (Fig. 4E, yellow arrows). The dendrites do not represent glue or artifacts of ground-section preparation, as they are also present on the partially demineralized bone floating in the EDTA solution (Fig. 4F). Some of the residues appear to ‘emanate’ from osteocyte lacunae and may be some diagenetic secondary recrystallizations ( Fig. 2F). The tracheal bone is composed of dense hydroxyapatite minerals. Remodeling of the tracheal bone tissue is evident in the presence of secondary osteons (Fig. 2 and Supplementary data). The cementing lines between different secondary osteons are visible because they have a higher degree of mineralization under the BSE (backscattered electron) mode. The haversian canals are filled largely by calcite precipitated during diagenesis (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2

新窗口打开|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT

新窗口打开|下载原图ZIP|生成PPTFig. 2SEM photographs of the fragment of fossil ostrich trachea (IVPP V 25336)

A. corresponding SEM image of tracheal sections in

Abbreviations: CFs. fossilized collagen fibers; O. fossilized remnant of osteocyte; OL. osteocyte lacuna; Trach. tracheal ring; ub. unaltered bone matrix

Fig. 3

新窗口打开|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT

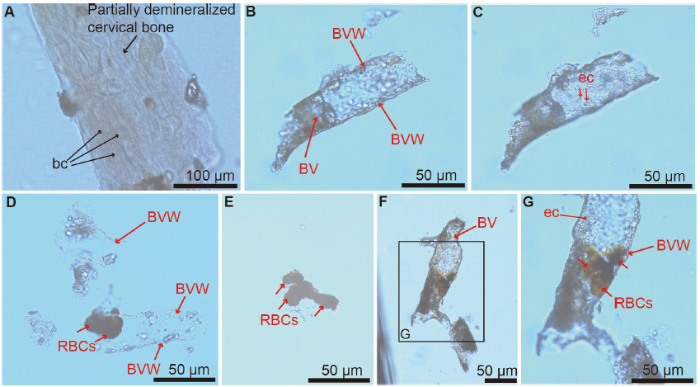

新窗口打开|下载原图ZIP|生成PPTFig. 3Photomicrographs of another demineralized fragment of Struthio cervical bone (IVPP V 25336)

A. partially demineralized bone using EDTA in sterile conditions. The bone is translucent and bacterial colonies are clearly visible. B. fossilized remnants of original blood vessels (freed from the bone matrix after complete demineralization) which present the same morphological characteristics of extant ostrich blood vessels (Schweitzer et al., 2005, 2007). The vessel is hollow, translucent, and shows clear walls.

C. same image as panel B shown in a slightly different focal depth to emphasize remnants of fossilized endothelial cell nuclei within the blood vessel walls. D. fragment of blood vessel with round brown microstructures that are consistent in location and morphology with fossilized blood content. E. fossilized intravascular content (potential blood breakdown products). F. fragment of blood vessel with internal content. G. close-up of endothelial cells in the thick blood vessel walls, and three distinct, circular to oval, brown structures that are most likely the fossilized remnants of original red blood cells

This vessel is not complete, but a branching pattern is obvious Abbreviations: bc. bacterial colony; BV. fossilized remnant of original blood vessel; BVW. fossilized remnant of blood vessel walls; ec. fossilized remnants of endothelial cell nuclei; RBCs. fossilized remnants of original red blood cells

Fig. 4

新窗口打开|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT

新窗口打开|下载原图ZIP|生成PPTFig. 4Photographs of the fragment of fossil ostrich trachea (IVPP V 25336)

A. photograph of the fragment (outlined in blue) prior to extraction; B. first histological cross section of the fragment seen under transmitted light; C. same image seen under polarized light, some brown material, potentially original soft-tissues with remnants of organic molecules is on top of the trachea; D. close-up of unaffected bone with no evidence of bacterial invasion; E. close-up of unaffected bone with dendritic structures (yellow arrows); F. partially demineralized bone with dendritic structures (yellow arrows) They emanate from the osteocyte lacunae, but are also present directly on the bone matrix so they may represent some type of diagenetic recrystallization

Abbreviations: BOM. potential brown organic matter; OL. osteocyte lacuna; Trach. tracheal ring; ub. unaltered bone matrix

3.2 Taphonomic alteration

The fragment of cervical bone was extremely altered histologically during burial and diagenesis. Under transmitted light, the bone matrix is characterized by many undulating beige areas within a lighter matrix (Figs. 5B-D, I). The beige areas correspond to preserved bacterial colonies, and the whiter areas correspond to unaffected bone matrix (Figs. 5B-D, I). The bacterial colonies are identifiable readily under SEM because of differences in apatite mineral density (Fig. 5E-F). The colonies are composed of channels and pores of around 0.3 μm in diameter ( Fig. 5D-G). Each channel and pore were made by an individual bacterium, and they represent Non-Wedl Microscopical Focal Destruction (MFD), as opposed to the Wedl tunneling made by fungi (Hackett, 1981). No clear evidence of fungal invasion is visible in these sections (e.g. compare with Fernandes-Jalvo et al., 2010:fig. 3.2).Fig. 5

新窗口打开|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT

新窗口打开|下载原图ZIP|生成PPTFig. 5Histological and SEM photographs of the fragment of Struthio sp. cervical vertebra (IVPP V 25336)

A. photograph of the fragment prior to extraction, outlined in red; B. histological cross section of the fragment under transmitted light; C. close-up showing highly altered bone microstructure; D. higher magnification shows elongated, beige areas that correspond to bacterial colonies within a lighter and unaffected bone matrix; E. corresponding SEM image of (C); F. a close-up of the bacterial colonies under the SEM; G. Higher magnification shows that the colonies are characterized by thin channels and pores (bc); H. second histological cross section of the fragment, with high pneumaticity and little amounts of bone; I. close-up showing microbially attacked bone; J. close-up on another region showing unaltered bone (without any bacterial colonies) and a vascular canal in the center; K. close-up of the vascular canal shows it is filled with a brown material, most likely organic remnants, some round structures are also seen, and they present the right size and location to be the fossilized remnants of original red blood cells; L. close-up (slightly more dorsal) shows a hollow, tubular structure with walls. It presents all of the morphological characteristics of extant ostrich blood vessels and blood vessel walls (Schweitzer et al., 2005, 2007)

All light microscopy photographs in this figure are shown under transmitted light Abbreviations: bc. bacterial colony; BOM. potential brown organic matter; BV. blood vessel (or fossilized remnants of original blood vessel); BVW. blood vessel wall (or fossilized remnants of original blood vessel wall); Cerv. cervical vertebra; OL. osteocyte lacuna; RBCs. red blood cells; ub. unaltered bone matrix; VC. vascular canal

Non-Wedl MFDs usually are accompanied by hypermineralized areas surrounding each bacterial colony (corresponding to much brighter areas as seen under the SEM). These hypermineralized areas are the result of the redeposition of bone mineral (hydroxyapatite; e.g. see Fernández-Jalvo et al. 2010:fig. 3). However, these hypermineralized areas are absent here (Figs. 5F, 6A). This absence indicates that either the bacterial invasion was truncated before redeposition of bone minerals could occur, or that the contrast settings of the SEM were not sensitive enough to display clear differences in apatite density. Alternatively, it is possible that not all types of bacteria induce redeposition of minerals.

The fragment of the ostrich cervical is highly pneumatized (Figs. 5B, H), and few bony trabeculae are present. The bacterial invasion of the bone did not have time to affect the entire bone matrix because there are completely unaltered bony areas (Fig. 5J-L). It also appears that in these unaltered areas, the original soft-tissue material, such as original blood-vessels and their contents, were preserved (Fig. 5E-F). In one specific area, a fossilized blood vessel (exhibiting clear blood-vessel walls) is preserved in a bony vascular canal (Fig. 5L). Three circular brown structures resembling the fossilized remnants of original red blood cells are also visible (Fig. 5K). The demineralization of the bone matrix in the adjacent fragment confirmed the above-described preliminary identifications (Fig. 3 and see next section).

Surprisingly, the bone matrix of the extracted tracheal ring fragment (Fig. 4A) does not show any evidence of bacterial invasion under transmitted light (Fig. 4B, D-E) or SEM (Fig. 2A-F). Since the cervical vertebra and the trachea clearly derive from the same individual, this difference shows that the bacterial invasion was restricted only to certain areas. This pattern could be the result of the bacteria not having enough time to enter all body parts after the ostrich’s death, or perhaps a preference for the microenvironments available in the pneumatic bone. Invading the bone may be easier through the more porous cervical bone, and more difficult in the less porous and more compact tracheal rings. The fragment of the trachea is covered by a thick transparent layer (most likely glue) (Fig. 4B), which also incorporates some potential soft tissue remnants resembling decayed organic matter (red arrows, Fig. 4B).

3.3 Soft tissue identification and description

We demineralized both the cervical fragment and the tracheal ring fragment, but soft tissues (i.e., the fossilized remnants of original blood vessels and red blood cells) were recovered only from the cervical fragment (Fig. 3). No soft-tissues were recovered from the tracheal ring (Fig. 4F). We do not think this is a true preservation signal, but rather simply the result of the presence of very few vascular canals in the ossified tracheal rings, as opposed to the highly vascularized and pneumatized cervical vertebra. We did not recover any remnants of original osteocytes in either sample even though we clearly see some in the tracheal ring fragment (e.g. Fig. 2B). This lack of recovery probably results from their very small size and the fact that we did not centrifuge or filter the demineralized material (to select only cell-sized material and isolate cells) during this study.Demineralization of the fossil cervical bone fragment freed preserved soft-tissue material from the bone matrix (Fig. 2) and revealed the presence of structures that possess all of the morphological characteristics of extant ostrich blood vessels (see Schweitzer et al., 2005, 2007). The vessel structures are hollow, translucent, and have clear walls ( Fig. 3B, D, F-G). Fossilized remnants of potential original endothelial cell nuclei are also visible (Fig. 3C, G). Some fragments of vessels have circular brown microstructures internally, and based on their shape and location, they are most likely fossilized blood contents (Fig. 3D-G) such as red blood cells or other blood and/or plasma decomposition products (see Schweitzer et al., 2007). One vessel fragment exhibits a branching pattern (Fig. 3F, G) inconsistent with fungal hyphae (see Schweitzer et al., 2005, 2007, 2014). Structures similar to those reported here (fossilized remnants of blood vessels, red blood cells, and endothelial cell nuclei) have already been reported in other vertebrate fossils from much older sediments, such as the dinosaur Tyrannosaurus rex from the Late Cretaceous of Montana (Schweitzer et al., 2005).

4 Discussion

4.1 Taphonomic alteration in Linxia Basin

The Linxia Basin has been reconstructed as a having a savanna or sub-arid steppe habitat since ~8.5 Ma (Deng, 2005). The strength of the Asian monsoon intensified by 8 Ma during the Late Miocene, and there was increased aridification across Central Asia related to the continuous uplift of Tibetan Plateau (Fang et al., 2003; Zheng et al., 2003, 2006; Fan et al., 2007). There are well-developed brown paleosols (luvic cambisols) in the Liushu Formation in the central part of the basin (e.g. Laogou). The paleosol beds have been thought to have formed during a warm and sub-arid steppe with seasonal variation (Zhang et al., 2019), and this setting could be the very early burial environment of the fossil described above. During ontogeny, the ostrich trachea arises as cartilage during embryonic development and is completely or partially replaced by bone later on. The trachea is attached to the cervical vertebrae via a ligament (Mclelland, 1989) and the preservation of the vertebrae with part of the trachea here indicates that the specimen likely was transported for only a short distance. Taphonomic work on Liushu Formation fossils indicates that the bone surface smoothness and weathering index support surface exposure of most fossils prior to burial for a few years at most (Liang andDeng, 2005). The mixture of taxa and breakage of the bones clearly indicate some past effects of water and/or wind transport on the fossil assemblage and its burial.Bacterial alteration or invasion of mineralized tissues can occur within 10 years after death and burial (Hedges, 2002; Pinhasi and Mays, 2008). It is most likely that the MFDs in the cervical bone occurred early during the bone burial phase in this fossil. Even though it is possible for bacteria to invade bone in vivo (e.g. during osteomyelitis; Junka et al., 2017), these MFDs are consistent with the postmortem bioerosion reported in many taphonomic studies (e.g. Fernandez-Jalvo et al., 2010). The mode and location of death also determines the chance for microbial alteration to occur in bone material. Invasion has been found within bones buried in soil (Turner-Walker and Jans, 2008; Turner-Walker, 2019). As mentioned above, these microbial borings in the ostrich vertebra might also form under similar conditions within paleosols (Zhang et al., 2019). Continuous microbial tunneling relies on cyclic wetting and drying environmental changes, suggesting that ground water availability might have fluctuated during the early burial of the fossil, driven by an intensified seasonal monsoon. Previous geochemical analyses of biomarkers (e.g. n-alkanes) demonstrate that a rich microbial community was present in these weakly oxidized-anoxic arid depositional environments ( Wang et al., 2010b, 2012). The microbial invasion of the vertebrae likely stopped because of a change in the microenvironment of the bone that may have resulted from larger scale changes such as cooling and increased aridification later in diagenesis (Ma et al., 1998). It is possible that the abundant crystalline calcite that precipitated and filled the porous areas of the bone also occurred during this stage and led to a cessation of the microbial activity (Fig. 4).

Calcite precipitation inside the bone is a remarkable feature observed in a wide variety of fossils, including fossils from the Liushu Formation (Liang and Deng, 2005). This mineralization happened relatively early in diagenesis and is potentially related to the rapid aridification that occurred during 8 Ma in the Late Miocene as indicated by paleoclimate proxies (Wang et al., 2010b, 2012). The sampled sediments surrounding the tracheal bone are composed of minerals like hematite, quartz, and clays, but they are poor in calcite (see Supplementary data). This key mineralogical difference presumably derives from the burial ground waters around/within the fossil and the adjacent sediments. These waters may have been influenced by seasonal water drainage changes from monsoons or longer-term climatic shifts related to aridification in the basin. Final burial appears to have occurred at least after the initiation of precipitation, based on broken calcite crystals in the broken bones (indicated by a tracheal section, see Supplementary data). The combination of short-term (bacterial invasion in less than hundreds of years) and longer-term diagenetic features in the specimens could indicate a certain degree of taphonomic reworking of the material with specimens deposited together representing a longer interval of time. We encourage further work to be done on the study of the interrelationships between fossil bones (with and without bacterial invasion or preserved micro soft tissues) and their associated sediments.

4.2 Soft tissue preservation

The preservation of remnants of original blood vessels and their contents in this fossil ostrich is not surprising, as many previous studies have reported these types of structures in fossils much older than the Miocene, such as Jurassic (Wiemann et al., 2018) and Cretaceous dinosaurs (Pawlicki et al., 1966; Pawlicki and Nowogrodzka-Zagórska, 1998; Schweitzer et al., 2005). Other evidence of preserved soft-tissue structures or fine cellular details is documented in Cambrian invertebrate embryo-like fossils found in Neoproterozoic phosphatized sediments (e.g. see Yin et al., 2007). Overall, considerable evidence has accumulated in recent decades that soft-tissues can easily be preserved in fossils for hundreds of millions of years (Briggs, 2003; Schweitzer et al., 2007; Bailleul et al., 2020). The microstructure of the material inside the bones presented here (Fig. 3) is not consistent with structures derived from microbes or fungi (e.g. fungal hyphae), and are almost identical to the same structures in extant homologues. Therefore, the most plausible conclusion is that these fossilized soft-tissues are endogenous to this extinct Linxia ostrich fossil.Even though the identification of soft-tissue presented here is entirely based on morphology and did not involve any histochemical nor molecular tests (e.g. using Energy Dispersive Spectroscopy or other methods), it is safe to hypothesize that original organic molecules are still preserved in this specimen. As demonstrated by previous studies, it is possible that the brownish stained residues that are present after decalcification (Fig. 3) are transferred proteinoids scaffolding via crosslinking, which may have been preserved in an oxidative setting (Wiemann et al., 2018). Moreover, an experimental study has shown that iron from heme compounds in red blood cells helps to stabilize the preservation of blood vessels in bone (Schweitzer et al., 2014). It is likely that iron from the surrounding sediments (Zhang et al., 2019) or red blood cells directly contributed to the preservation of these fossilized vessels. Testing the presence of iron in these fossilized remnants, as well as much more robust histochemical and molecular analyses (e.g. proteomic analyses) should be done in the future on this specimen and on additional Liushu material.

5 Conclusions

Our results suggest that vertebrate fossils from the fine-grained sediments of the Liushu Formation display a special category of exceptional internal preservation where no external soft tissues of the integument (e.g. feathers or hairy integuments and skin impressions) are present. We encourage the investigation at the molecular level of additional soft-tissues from the Liushu Formation in order to determine if this exceptional preservation extends beyond microscopy to the biomolecular level. The microscopic data presented here provide a unique perspective to aid in interpreting the burial environment of the bone when the fossil-bearing siltstone and red clay was deposited (Fan et al., 2007). A recurring of wetting and drying cycles in control of oxygen level is suggested to have facilitated the microbial alteration that is found in the ostrich cervical vertebrae ( Turner-Walker, 2019). In addition, extensive precipitated calcite crystals within the open spaces of the bird bones enhanced our previous understanding for the fast aridification during the Late Miocene (Fan et al., 2007). This study shows the potential for developing an integrated understanding that links paleoenvironmental factors with data from taphonomy, geochemistry, paleohistology, soft-tissue and molecular studies. This combination of microscopic morphology with geological and geochemical proxies can provide insights into preservational and diagenetic processes in the fossil record. Increasing the accuracy of the geological age of the Linxia Basin fossils with corresponding paleomagnetic dates in measured stratigraphic sections should aid future researchers to better understand the interrelationships between climatic settings when the Miocene birds and mammals were alive, as well as the nature of their death.Acknowledgments

Funding from CAS One Hundred Talents Project (KC217113) to ZL; the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC41772013) to ZL and TAS; and the Strategic Priority Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Grant No. XDA 9050102, XDA20070203, and XDB26000000), and CAS-PIFI (President’s International Fellowship Initiative) to AMB are thanked. This study was also funded by Second Tibetan Plateau Scientific Expedition and Research Grant 2019QZKK0705. We also thank Liu Xinzheng for preparing the sample, Gao Wei for photographs, and Zhang Shukang and Jiang Zhengcheng for preparing the ground sections. We also thank Zhou Zhonghe, Pan Yanhong, and Yinmai O’Connor for their comments that helped improve the manuscript.Supplementary material can be found on the website of Vertebrata PalAsiatica (

参考文献 原文顺序

文献年度倒序

文中引用次数倒序

被引期刊影响因子

[本文引用: 2]

DOIURL [本文引用: 1]

[本文引用: 1]

DOIPMID [本文引用: 1]

The remains of ovarian follicles reported in nine specimens of basal birds represents one of the most remarkable examples of soft-tissue preservation in the Early Cretaceous Jehol Biota. This discovery was immediately contested and the structures alternatively interpreted as ingested seeds. Fragments of the purported follicles preserved in an enantiornithine (STM10-12) were extracted and subjected to multiple high-resolution analyses. The structures in STM10-12 possess the histological and histochemical characteristics of smooth muscles fibers intertwined together with collagen fibers, resembling the contractile structure in the perifollicular membrane (PFM) of living birds. Fossilized blood vessels, very abundant in extant PFMs, are also preserved. Energy Dispersive Spectroscopy shows the preserved tissues primarily underwent alumino-silicification, with minor mineralization via iron oxides. No evidence of plant tissue was found. These results confirm the original interpretation as follicles within the left ovary, supporting the interpretation that the right ovary was functionally lost early in avian evolution.

DOIURL [本文引用: 1]

DOIURL [本文引用: 1]

[本文引用: 4]

[本文引用: 1]

[本文引用: 3]

[本文引用: 4]

DOIURL [本文引用: 4]

DOIURL [本文引用: 3]

DOIURL [本文引用: 2]

PMID [本文引用: 2]

DOIURL [本文引用: 1]

DOIURL [本文引用: 1]

DOIURL [本文引用: 1]

DOIURL [本文引用: 1]

DOIURL [本文引用: 1]

DOIURL [本文引用: 1]

[本文引用: 1]

DOIURL [本文引用: 2]

[本文引用: 2]

[本文引用: 1]

PMID [本文引用: 1]

Dinosaur bones, 80 million years old, were studied in the scanning electron microscope, and subjected to X-ray microanalysis. Samples for the investigations were prepared according to specially elaborated, and simultaneously described methods. Analysed were (a) the morphological structure of the blood vessels and (b) the remains of their contents. The walls of the blood vessels were found to be morphologically identical with those in present-day reptiles. Bodies were found at several places inside the vessels which strongly remind one of erythrocytes in modern bones. X-ray microanalysis of places where these bodies were accumulated revealed much higher levels of iron, than at any other regions of the blood-vessel wall. Further analysis of the "dinosaur erythrocyte" iron content could be a starting point for the possible determination of oxygen in the earth's atmosphere, 80 million years ago.

DOIURL [本文引用: 1]

DOIURL [本文引用: 1]

[本文引用: 1]

DOIURL [本文引用: 1]

[本文引用: 1]

PMID [本文引用: 6]

Soft tissues are preserved within hindlimb elements of Tyrannosaurus rex (Museum of the Rockies specimen 1125). Removal of the mineral phase reveals transparent, flexible, hollow blood vessels containing small round microstructures that can be expressed from the vessels into solution. Some regions of the demineralized bone matrix are highly fibrous, and the matrix possesses elasticity and resilience. Three populations of microstructures have cell-like morphology. Thus, some dinosaurian soft tissues may retain some of their original flexibility, elasticity, and resilience.

PMID [本文引用: 6]

We performed multiple analyses of Tyrannosaurus rex (specimen MOR 1125) fibrous cortical and medullary tissues remaining after demineralization. The results indicate that collagen I, the main organic component of bone, has been preserved in low concentrations in these tissues. The findings were independently confirmed by mass spectrometry. We propose a possible chemical pathway that may contribute to this preservation. The presence of endogenous protein in dinosaur bone may validate hypotheses about evolutionary relationships, rates, and patterns of molecular change and degradation, as well as the chemical stability of molecules over time.

[本文引用: 1]

DOIURL [本文引用: 2]

DOIURL [本文引用: 1]

[本文引用: 2]

DOIURL [本文引用: 1]

DOIURL [本文引用: 4]

[本文引用: 3]

DOIURL [本文引用: 2]

DOIURL [本文引用: 1]

DOIURL [本文引用: 5]

DOIURL [本文引用: 1]

DOIURL [本文引用: 1]

[本文引用: 1]

DOIURL [本文引用: 2]