,1,21Center of Soft Matter Physics and its Applications,

,1,21Center of Soft Matter Physics and its Applications, 2School of Physics,

Received:2020-12-11Revised:2021-01-5Accepted:2021-01-9Online:2021-02-16

Abstract

Keywords:

PDF (1754KB)MetadataMetricsRelated articlesExportEndNote|Ris|BibtexFavorite

Cite this article

Xiuyuan Yang, Zechao Jiang, Peihan Lyu, Zhaoyu Ding, Xingkun Man. Deposition pattern of drying droplets. Communications in Theoretical Physics, 2021, 73(4): 047601- doi:10.1088/1572-9494/abda21

1. Introduction

The drying of water droplets on window glass after it has rained is commonly observed in daily life. Droplets drying looks like a simple problem, but shows surprisingly complicated fundamental science, including evaporation, particle convection, contact line (CL) motion, etc. When the droplets are laden with nonvolatile solutes and evaporate on a solid surface, this phenomenon becomes even more complex because versatile deposition patterns of solutes are left on the substrate. To understand the dynamics of the drying of liquid droplets and to tailor or control the final deposition pattern has not only held a special interest in scientific research, but important applications in inkjet printing [1–3], microelectronic device manufacturing [4] and even medicinal diagnostics [5, 6]. As Larson pointed out in his review published in Nature that ‘In modern times, a world of physical chemistry can similarly be observed by watching a droplet dry' [7], the drying of liquid droplets has spawned thousands of publications, which lie at the crossroad of physics, chemistry, materials science and even biology. In this topical review, we will give brief descriptions of the scientific advances in the understanding of droplets drying. We will first review the versatility of the deposition patterns, mainly about ring-like patterns, of drying sessile droplets that were observed in experiments. Then, we show the recent development of the theoretical studies of the drying of liquid droplets based on the Onsager variational principle (OVP) theory.1.1. Ring-like patterns in experiments

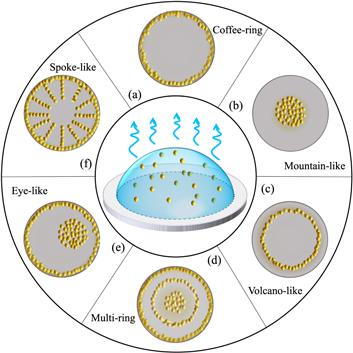

In 1997, Deegan et al reported that a spilt droplet of coffee leaves a circular ring, rather than a uniform spot after drying on a coffee mug [8]. This is known as the famous coffee-ring phenomenon. Inspired by this seminal work, other ring-like patterns have been subsequently reported, including mountain-like [9–11], volcano-like [12, 13] and even multi-ring patterns [14, 15]. Besides ring-like patterns, a large number of complicated deposition patterns have recently been found in experiments, such as eye-like [16], finger-like [17], spoke-like [18] and spiral patterns [19], as shown in figure 1. As a special topical review, we hereafter review the formation mechanism of the ring-like deposition patterns in terms of both experimental and theoretical aspects.Figure 1.

New window|Download| PPT slide

New window|Download| PPT slideFigure 1.Schematic diagram of experimentally observed deposition patterns of drying droplets: (a) coffee-ring; (b) mountain-like; (c) volcano-like; (d) multi-ring; (e) eye-like; (f) spoke-like, which are the density distribution of solutes left on the substrate after droplet drying.

The coffee-ring pattern, figure 1(a), is usually observed in our daily life, where most solutes are deposited along the initial perimeter of the droplet. Deegan [8, 20] first pointed out that the formation mechanism of coffee-ring is the combined effects of the pinning of the CL and the evaporation-induced fluid flow inside the droplets. When the CL is pinned, the direction of the height-averaged fluid flow inside the droplet is from the droplet center to the edge. Such convection flux causes the nonvolatile solutes to accumulate and then deposit in the area around the CL, forming the coffee-ring pattern. In recent years, the utilization and suppression of the formation of coffee-ring has been applied to many aspects of industrial production [1, 21] and for more details one can refer to another recent review [22].

On the other hand, a freely moving CL leads to a mountain-like deposition pattern, where most of the solutes deposit at the center of the droplet [figure 1(b)]. Pauchard and Allain [23] studied the drying of a water/polysaccharid Dextran droplet on a clean glass slide. They found that when the polymer concentration is around 0.20 g/ml and the relative humidity about ±5%, a mountain-like deposition pattern is left on the slide. Later, Willmer et al [9] studied aqueous poly(ethylene oxide) solution droplets drying on glass substrates. They also obtained the mountain-like deposition pattern and found that the radius of the deposition pattern continuously increased to the size of the droplet's initial radius by increasing the concentration of polymer. Besides the solute concentration, Li et al [11] found that the wetting characteristics of the droplet solution with respect to the substrate, i.e. the contact angle hysteresis (CAH), is another important factor in obtaining the mountain-like pattern. With a weak CAH substrate (such as a silica glass or polycarbonate substrate for the water droplet), the CL freely recedes and forms the mountain-like deposition pattern.

When the moving ability of the CL is in between the pinned and freely moving cases, volcano-like patterns are observed, of which the peak of the density distribution of the deposited solutes is located between the droplet center and its initial perimeter, as shown in figure 1(c). Kajiya et al [12] studied the drying of a water-poly(N, N-dimethylacrylamide) PDMA droplet on a glass substrate and observed a volcano-like deposition pattern. They showed that the location of the peak approaches the initial perimeter as the equilibrium contact angle of the droplet increases by using different glass slides as the substrates. They explained the volcano-like pattern based on the mobility of the CL. They showed that both the CL and solutes move from the droplet edge to the center. However, the CL moves faster than the solutes, forming the volcano-like deposition pattern.

When the CL has a stick-slip motion, the deposits form concentric rings called a multi-ring deposition pattern, as shown in figure 1(d). In these cases, the droplet CL is first pinned, generating a flow from the droplet center to its edge. This flow convects solutes to the boundary and deposits them near the CL. This process is similar to the formation of the coffee-ring. The difference is that as the droplet volume decreases, the contact angle decreases and creates an inward unbalanced force acting on the CL. When the contact angle becomes less than the receding contact angle, the CL starts to slip and move quickly towards the center accompanied by the increase of the contact angle. The CL keeps receding until the contact angle increases to its equilibrium value. The repetition of this stick-slip motion of the CL forms the multi-ring deposition pattern.

In 1995, even earlier than the observation of the coffee-ring, Adachi et al [24] observed the multi-ring pattern in the drying of water-polystyrene particle droplets on borosilicate glass plates. Later, Deegan et al [25] also found such interesting deposition patterns in the drying of the same droplets on mica, but with a different solute size of the polystyrene particle (0.1 μm). Figure 2(a) is the experimental results of the multi-ring pattern found in the evaporation of deionized water-DNA droplets on glass surfaces. An interesting phenomenon is that the multi-ring pattern is made of a solid circle surrounded by many concentric rings. Besides sessile droplets, confined evaporation systems can also generate the multi-ring deposition pattern. In figure 2(b), Xu et al [14] obtained these patterns when a solution evaporated on the sphere-on-flat geometry, where the solution is made by poly[2-methoxy-5-(2-ethylhexyloxy)-1,4-phenylenevinylene] (MEH-PPV) (MW = 50–300 kg/mol) and toluene.

Figure 2.

New window|Download| PPT slide

New window|Download| PPT slideFigure 2.Examples of multi-ring patterns through the evaporation of droplets. (a) Typical DNA stain patterns with multi-ring formation. Reprinted figure with permission from [15]. Copyright (2020) the American Physical Society. (b) MEH-PPV ring patterns in a sphere-on-flat configuration. Reprinted figure with permission from [14]. Copyright (2020) the American Physical Society.

It is clear that the final deposition pattern is mainly determined by the motion of the CL. Many experimental conditions, including the evaporation rate, viscosity of the solution, wetting property of the substrate, etc, can affect this motion. Various combinations of these factors result in versatile deposition patterns. In fact, we are far from discovering all the possible droplet deposition patterns [26].

1.2. Conventional hydrodynamic theory of drying droplets

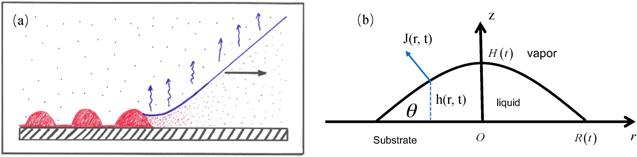

In this subsection, we briefly review the development of the conventional hydrodynamic theory of drying droplets. We will review the basic theoretical framework. Some simple reduced scale theories are also reviewed here, to give fundamental understanding of this complex problem.The deposition pattern is the density distribution of nonvolatile solutes left on the substrate after droplets have dried. Figure 3(a) describes the process of the deposition. The solutes are convected to the CL by the evaporation-induced fluid flow and then left behind as the CL recedes. Therefore, the fluid flow inside the droplet and moving ability of the CL are two crucial factors in determining the final deposition pattern. Calculating the flow velocity and motion of the CL during evaporation is the main task of theoretical models of drying.

Figure 3.

New window|Download| PPT slide

New window|Download| PPT slideFigure 3.(a) Sketch of the essential core part of the geometry of every deposition process where material is left behind by a moving CL of suspension or solution with a volatile solvent. Reprinted from publication [27]. Copyright (2020), with permission from Elsevier. (b) Schematic of a droplet with axis-symmetry in a cylindrical coordinate system (side view). Relevant parameters are the radius of the CL R(t), height of the droplet at the center H(t), contact angle θ(t), evaporation rate J(r, t) and profile of liquid-vapor interface h(r, t).

For simplicity, common assumptions used in the theory are that a sessile droplet has axis-symmetry in a cylindrical coordinate, as shown in figure 3(b), and the solutes have the same height-averaged radial velocity as the solvent [25, 28]. The latter assumption is valid for droplets where the size of the laden particles is large enough to neglect its diffusion, and on the other hand, it should be small enough to neglect the sedimentation (vertical motion) [25] . Once we have the velocity field of the evaporation-induced fluid flow, we have the motion of all solutes.

It is known that the fluid flow inside the droplet is determined by the shape evolution of the droplet, which is often described by the liquid/vapor interface profile h(r, t). According to the conservation of mass [equation (

Let us consider the J(r, t) first. The evaporation process of droplets has been studied both experimentally and theoretically for many years. Various evaporation models have been proposed in theory [20, 27, 29], including J = J0, $J={J}_{0}$ and $J={J}_{0}\exp (-{{Ar}}^{2})$, where J0 and A are the phenomenological constant. Usually, the evaporation rate can be obtained by the vapor-liquid diffusion model [30, 31].

First, the distribution of vapor concentration c(r, t) can be solved by the diffusion equation,

Figure 4.

New window|Download| PPT slide

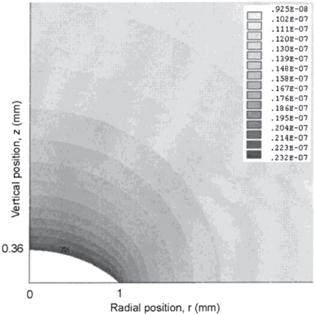

New window|Download| PPT slideFigure 4.Contour plot of the vapor concentration distribution above a droplet of radius R = 1 mm and height h0 = 0.364 mm. Parameters used in the FEM method are vapor diffusivity D = 26.1 mm2/s, relative humidity H = 0.40 and saturated vapor concentration on the droplet surface cv = 2.32 × 10−8 g/mm3. Gray bars represent the vapor concentration in g/mm3. Reprinted with permission from [31]. Copyright (2020) the American Chemical Society.

Besides the FEM calculations of the evaporation rate, Deegan et al [20, 31] analyzed the evaporation of spherical-cap droplets by mimicking the problem to the calculation of the electrostatic potential of a charged conductor with a similar droplet shape. They obtained an analytical expression of the evaporation rate,

Given the evaporation rate, the velocity field of the fluid flow inside the droplet can be obtained by solving the continuity and Navier–Stokes equations. For the quasi-steady process, the inertia term can be neglected. Then, the equations in a cylindrical coordinate are,

Figure 5.

New window|Download| PPT slide

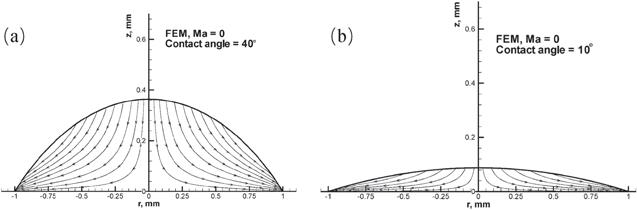

New window|Download| PPT slideFigure 5.Streamline plots of the evaporation-induced fluid flow inside the droplets from the FEM for droplets with a contact angle of (a) 40° and (b) 10°. Reprinted with permission from [32]. Copyright (2020) the American Chemical Society.

It is difficult to obtain an analytical solution of the full model mentioned above. Assumptions have been applied to the full model for special cases to obtain analytical solutions. When the droplet contact angle is small, the lubrication approximation can been applied to reduce the model by ignoring the vertical velocity uz. The reduced model was given as [33, 34]:

Experiments observed two special evaporation modes of drying droplets: the constant contact angle (CCA) and the constant contact radius (CCR) modes, where either the contact angle or contact radius is nearly unchanged during evaporation. For these two cases, analytical solutions of the radial velocity can be obtained. Deegan et al [20] combined the global mass of conservation [equation (

In conclusion, the conventional hydrodynamic theory has been mostly based on the conservation law and N-S equations. Under the basic framework, the main task is to solve the high-order partial differential equations (PDEs) [equation (

Besides theory, simulations such as the Monte Carlo (MC) [37–43], molecular dynamics (MD) [44–46], density functional theory (DFT) [43, 47–52] and the lattice Boltzmann method (LBM) [53–59] are also used to study the drying of liquid droplets. Simulations such as experiments can provide some insight into these problems, which is very useful to construct the theoretical model. A detailed review of the simulation of drying droplets was given by Thiele et al [43].

2. OVP theory of drying droplets

In this section, we will review the OVP theory of the evaporation process and the formation of the deposition pattern of drying droplets. We show how such a theoretical framework can be formalized and the essential physics underlying this drying problem. We further show that such a simple theory can be used as the basis of MC simulation to predict deposition patterns in high dimension and even for cases without radial symmetry.For a soft matter system, we can usually choose a set of parameters x = (x1, x2, ⋯ , xn) to describe the state of the system. If it is a force free system, i.e. the dissipation force is balanced by the potential force, then the time evolution of the system can be obtained as:

In 1931, Onsager noticed that many phenomenological equations for the time evolution of non-equilibrium systems have the same structure as those of particle-fluid systems [60, 61]. Then, with the Onsager's reciprocal relation ζij = ζji, we can construct time-evolution equation (

This theoretical framework is useful to construct not only conventional hydrodynamic equations, but some unknown evolution equations for complex soft matter problems [62, 63]. These dynamic equations are usually high-order partial differential equations, which require complicated numerical solutions. In recent years, Doi and co-workers found that the OVP theory can be used as a tool of approximation to derive first-order evolution equations of non-equilibrium systems. Such simple models simplify the numerical calculations or can even be solved analytically, bringing insightful fundamental understanding of non-equilibrium systems.

We use the sessile droplet as an example of how we use the OVP theory to study non-equilibrium problems. For a liquid droplet evaporating on the substrate, we consider R(t) as the droplet contact radius and H(t) as the height in the center. The surface profile is described by h(r, t) at time t, which is the same as figure 3(b).

Applying the lubrication approximation, the energy dissipation due to the fluid flow inside the droplet can be written as:

The free energy F is the sum of the interfacial energy:

We first show that minimizing the Rayleighian function without any assumption is a systematic way of constructing the corresponding conventional hydrodynamic equation.

The height-averaged velocity satisfies the conservation law,

Then, the time change of the free energy can be obtained from equations (

Inserting the expression v(r) into equation (

Actually, we can follow the same procedure to construct most conventional hydrodynamic equations and even for problems when we do not know their dynamic equations. These hydrodynamic equations are usually high-order partial differential equations that require complicated numerical solutions. The OVP theory can be further used as an approximation to reduce high-order PDEs to first-order dynamic equations. Then, the numerical solutions become much simpler and even analytical solutions can be obtained.

The droplet drying model equation (

For the entire evaporation process, the volume change rate $\dot{V}(t)$ is known to be proportional to the contact radius R(t),

It is worth noting that a realistic evaporation rate should be a spatial function of r and can even be divergent at the CL. Although this homogeneous evaporation rate is used to simplify the model, the series of works reviewed here showed that ignoring the position dependence of the evaporation rate is reasonable in the study of the ring-like deposition patterns of drying droplets. However, if one wants to study more complicated deposition patterns or focus on the shape evolution of drying droplets, a spatially dependent evaporation rate has to be used.

Combining equations (

On real surfaces, there is an extra energy dissipation due to the CL motion, which should be considered in the dissipation function,

We now turn to the free energy of the system. As we choose R and V as the slow variables, the free energy will be written as a function of the two slow variables. By assuming a parabolic form of the droplet interface profile, the free energy now has an explicit expression:

2.1. Shape evolution equations of evaporating droplets

The droplet shape evolution is described by $\dot{R}$ and $\dot{\theta }$, which can be obtained from the above Rayleighian function. The time evolution of contact radius $\dot{R}(t)$ is obtained by $\partial {\mathfrak{R}}/\partial \dot{R}=0$. Combined with the evaporation rate, equation (Here, we define ${k}_{\mathrm{ev}}={\tau }_{\mathrm{re}}/{\tau }_{\mathrm{ev}}$ to represent the evaporation rate and kcl = ξclθ/3Cη to describe the moving ability of the CL. It is clear that the set of equations (

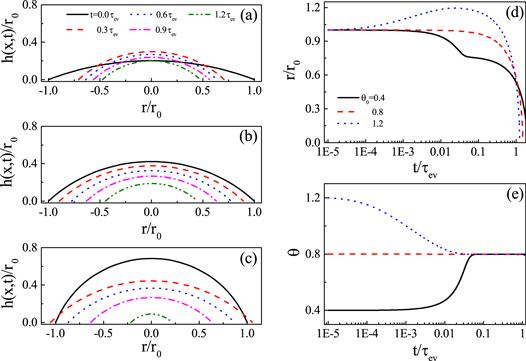

We notice that the parabolic assumption [equation (

Figure 6.

New window|Download| PPT slide

New window|Download| PPT slideFigure 6.Droplet shape evolution for evaporation on frictionless substrate for three situations: (a) θ0 < θe, (b) θ0 = θe and (c) θ0 > θe. Corresponding evolution of the CL r/r0 is shown in panel (d) and the contact angle θ is shown in panel (e). For all calculations, θe = 0.8 and kev = 0.001. Reproduced with permission from [65].

2.2. Deposition patterns

After obtaining the droplet shape evolution, we now discuss how to calculate the deposition patterns. Moreover, we will show that the dynamic model from the OVP theory can also be used for the MC simulations of deposition patterns for high-dimensional and two-droplet systems.We assume that the velocity of the solute is the same as the solvent given by equation (

Therefore, $\mu \left[\tilde{r}({r}_{0},{t}_{d})\right]$ gives the final density distribution of the deposited solutes on the substrate. In a short summary that when $\tilde{r}({r}_{0},{t}_{d})=R({t}_{d})$, solute with an initial position r0 deposits at time td and at the position of R(td). The final deposition pattern is described by $\mu \left[\tilde{r}({r}_{0},{t}_{d})\right]$.

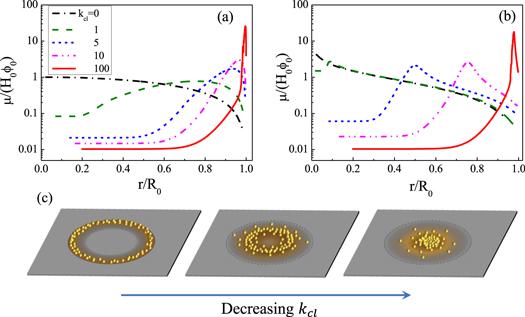

A series of works about the study of deposition patterns of drying droplets have been conducted by using the above-mentioned theoretical framework. In [64], Man and Doi clarified how the CL friction (described by kcl) and the evaporation rate (described by kev) affect the final deposition pattern. Figure 7 shows that the deposition pattern changes continuously from a coffee-ring to volcano-like and to mountain-like as the kcl increases. When kcl = 100, the CL hardly moves from the initial position and the coffee-ring pattern appears. On the other hand, when kcl = 0, the CL recedes freely and a mountain-like pattern appears. Especially when the evaporation rate is fast (kev ≫ 1), the model reduces to a simple form and an analytical expression of the peak position of the pattern rp can be obtained as:

Figure 7.

New window|Download| PPT slide

New window|Download| PPT slideFigure 7.(a) and (b) are the profile of the deposits left on the substrate when the drying is completed. Transition from coffee-ring to volcano-like and then mountain-like pattern induced by changing the value of kcl from 100 to 0. (a) The case of a fast evaporation rate characterized by kev = 1 and (b) the case where the evaporation rate is small with kev = 10−3. For both cases, θe = θ0 = 0.2 and Δt/τev = 10−5. (c) Sketch map of the transition from coffee-ring to mountain-like pattern. Reprinted figure with permission from [64]. Copyright (2020) the American Physical Society.

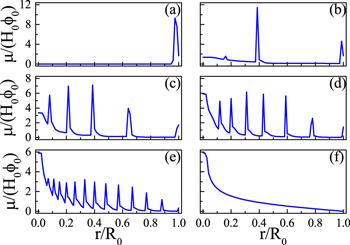

Instead of taking kcl as constant, Wu et al [67] assumed that it has two values, a low value for freely moving CL and a high value for pinned CL, written as:

Figure 8.

New window|Download| PPT slide

New window|Download| PPT slideFigure 8.Various multi-ring deposition patterns of drying droplets with different values of θR: (a) 0.00, (b) 0.08, (c) 0.16, (d)0.24, (e) 0.32 and (f) 0.4. The larger θR is, the higher the moving ability of the CL. For all calculations, θ0 = θe = 0.4, R0 = 4 and kev = 10−3. Reprinted with permission from [67]. Copyright (2020) the American Chemical Society.

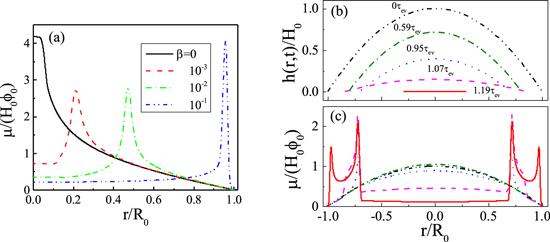

Later, Wu et al [68] proposed an extended model based on the OVP theory for the drying of liquid droplets of surfactant solutions. Surfactants can change the droplet liquid/vapor surface tension,

Figure 9.

New window|Download| PPT slide

New window|Download| PPT slideFigure 9.(a) shows the effect of a surfactant in the deposition patterns. When the initial surfactant concentration β is increased, the deposition pattern changes from mountain-like to volcano-like and then to coffee-ring pattern. All parameters are kcl = 0, kev = 0.002 and α = 1.0. (b) and (c) are the formation of the two-ring deposition pattern; (b) is the evolution of the profile of the surface and (c) is the evolution of the density distribution of solutes left on the substrate, μ(r, t)/(H0φ0). For (b) and (c), kev = 10−4, kcl = 0, α = 0.3 and β = 0.1. Reprinted with permission from [68]. Copyright (2020) the American Chemical Society.

The model is not limited to the single-droplet system and can be extended for the study of the drying of two droplets. Hu et al [69] studied the drying of two neighboring droplets, focusing on the corresponding deposition patterns. The two droplets evaporate simultaneously and each affects the evaporation of the other. Therefore, the evaporation rate does not have axis-symmetry anymore and an asymmetric evaporation rate J(r, t) has to be used,

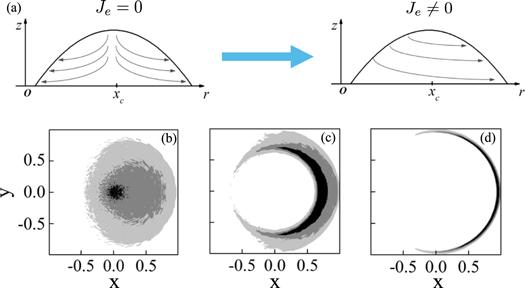

Figure 10.

New window|Download| PPT slide

New window|Download| PPT slideFigure 10.(a) is the sketch map of the influence of the existence of asymmetric evaporation rate Je in the evaporation-induced fluid flow inside the droplet. (b), (c) and (d) are the asymmetric deposition patterns calculated by the MC simulation. (b) Fan-like deposition is obtained when kcl = 0 and an asymmetric volcano-like deposition pattern is obtained when kcl = 10. (c) Eclipse-like deposition pattern is obtained when kcl = 50. For all the calculations θe = θ0 = 0.2, Δt/τev = 10−5, kev = 0.001 and Je = 0.3. Adapted with permission from [69]. Copyright (2020) the American Chemical Society.

3. Perspectives and conclusion

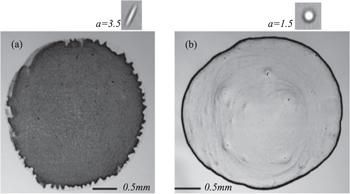

We gave detailed descriptions of how to use the OVP theory to construct a conventional hydrodynamic equation of drying droplets. Moreover, we also showed how to use the OVP theory as an approximation tool to reduce a high-order PDE to the first-order ordinary equation of drying droplets. The OVP theory can be treated as a systematic way to study non-equilibrium problems in soft matter. How to choose the proper slow variables of a given problem is one of the key challenging issues in applying this theory. Some extension of the model given in this review can be used to tackle these various problems, like the drying of droplets that contain different shapes of solute particles and the drying of thin film. Wang et al [70] have taken into account the contact angle hysteresis (CAH) based on the model in [64] and analyzed the effects of the CAH on the coffee-ring deposition. Xu et al [71] employed the OVP theory to derive the evolution equations of a mixture of binary fluid thin film. We believe that besides droplet systems, the drying of thin films and the corresponding deposition patterns can be well studied by the OVP theory reviewed here.In 2011, Yodh et al [72] pointed out that the coffee-ring effect can be suppressed by shape-dependent capillary interactions. In the experiments, they dried water drops containing a suspension of micrometer-sized polystyrene spheres stretched asymmetrically to different aspect ratios. Results showed that droplets laden with sphere particles form coffee-ring patterns, but with ellipsoidal particles can form uniform thin film, as shown in figure 11(a). It is clear that the shape of the solute particles provides a new way to control the deposition patterns. Besides particle shape, Patil et al [73] proved that particle size can also change the patterns. When ambient temperature is Ts = 27°, smaller monodispersed colloidal polystyrene particles (dP = 0.1, 0.46 and 1.1 μm) form mountain-like deposits on the wet-oxidized silicon surface after the water dried, whereas larger particles (dP = 3 μm) left ring formation. Indeed, it is similar to mountain-like deposition where particles concentrate in the center. When the radius of droplets is beyond the capillary length, we have to consider the effect of gravity on the deposition patterns [74, 75]. This effect is especially important when droplets are on inclined surfaces, which has been discussed both theoretically and experimentally [76, 77].

Figure 11.

New window|Download| PPT slide

New window|Download| PPT slideFigure 11.Images of the final distributions of ellipsoids (a) and spheres (b) after evaporation. Coffee-ring pattern changes to a uniform thin film by replacing the spherical solutes with ellipsoidal solutes, while all other experimental conditions remain the same. Reprinted by permission from [72], Copyright (2020).

From recent experimental studies, we can generally identify two new factors in tailoring the final deposition pattern of drying droplets. First, the properties of the solute can largely affect the final deposition pattern. We may include these effects by adjusting the diffusion coefficient in the model. The second one is the effect of gravity. This effect can be inserted into the model by introducing an extra term into the free energy. Then, one can analyze the effect of gravity on the fluid flow inside the droplets and see this effect in the final deposition patterns. The development of the OVP theory in soft matter is still at the beginning stage. Various successful examples of using this theory to deal with dynamic problems are still needed to enrich the understanding of the OVP theory.

In this review, we have shown the theoretical framework of the formation of the deposition pattern of drying droplets. By using the OVP theory proposed by Lars Onsager, the high-order conventional hydrodynamics equations can be reduced to first-order evolution equations, which provides us with a new way to understand these complex problems and makes the physical picture clearer. Based on the evolution framework, the formation mechanism of different ring-like patterns has been analyzed and explained. The purpose of this review is to introduce the background of the research on deposition patterns and also review the recent development of the OVP theory in drying droplets. We hope that this short review can help readers who are interested in this problem and especially help readers to build their own models of soft matter dynamic problems of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 21 822 302), the joint NSFC-ISF Research Program, China (Grant No. 21 961 142 020) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, China.Reference By original order

By published year

By cited within times

By Impact factor

DOI:10.1088/1361-6501/ab16b3 [Cited within: 2]

DOI:10.1016/j.snb.2017.06.045

DOI:10.1002/adma.201103032 [Cited within: 1]

DOI:10.1021/ja210430b [Cited within: 1]

DOI:10.1109/MEMB.2005.1411354 [Cited within: 1]

DOI:10.1038/s41598-018-27959-0 [Cited within: 1]

DOI:10.1038/550466a [Cited within: 1]

DOI:10.1038/39827 [Cited within: 2]

DOI:10.1039/b922727j [Cited within: 2]

DOI:10.1021/la400948e

DOI:10.1021/la501438k [Cited within: 2]

DOI:10.1021/la900216k [Cited within: 2]

DOI:10.1021/am400632s [Cited within: 1]

DOI:10.1103/PhysRevLett.96.066104 [Cited within: 3]

DOI:10.1103/PhysRevLett.100.044503 [Cited within: 2]

DOI:10.1039/C5SM00654F [Cited within: 1]

DOI:10.1021/acs.langmuir.9b02965 [Cited within: 1]

DOI:10.1140/epje/i2014-14084-3 [Cited within: 1]

DOI:10.1021/acs.langmuir.9b01002 [Cited within: 1]

DOI:10.1103/PhysRevE.62.756 [Cited within: 4]

DOI:10.1021/la050764y [Cited within: 1]

DOI:10.1016/j.cis.2017.12.008 [Cited within: 1]

DOI:10.1209/epl/i2003-00457-7 [Cited within: 1]

DOI:10.1021/la00004a003 [Cited within: 1]

DOI:10.1103/PhysRevE.61.475 [Cited within: 3]

DOI:10.1002/anie.201108008 [Cited within: 1]

DOI:10.1016/j.cis.2013.11.002 [Cited within: 3]

DOI:10.1039/C4SM02133A [Cited within: 2]

DOI:10.1021/la015518a [Cited within: 1]

DOI:10.1016/0021-9797(77)90396-4 [Cited within: 1]

DOI:10.1021/jp0118322 [Cited within: 5]

DOI:10.1021/la047528s [Cited within: 2]

DOI:10.1016/j.ces.2004.02.006 [Cited within: 2]

DOI:10.1063/1.3453799 [Cited within: 1]

DOI:10.1021/la902666r [Cited within: 1]

DOI:10.1039/c2sm25319d [Cited within: 1]

DOI:10.1021/jp063668u [Cited within: 1]

DOI:10.1021/jp803399d

DOI:10.1103/PhysRevE.78.041601

DOI:10.1103/PhysRevLett.99.116103

DOI:10.1103/PhysRevLett.100.176102

DOI:10.1021/jp312021w

DOI:10.1088/0953-8984/21/26/264016 [Cited within: 3]

DOI:10.1039/c3sm50530h [Cited within: 1]

DOI:10.1021/la500513x

DOI:10.1038/srep17521 [Cited within: 1]

DOI:10.1016/j.cis.2014.12.003 [Cited within: 1]

DOI:10.1080/00018730310001615932

DOI:10.1063/1.478705

DOI:10.1088/0953-8984/12/8A/356

DOI:10.1021/acs.langmuir.7b03096

DOI:10.1017/S0022112096000237 [Cited within: 1]

DOI:10.1146/annurev.fluid.30.1.329 [Cited within: 1]

DOI:10.1146/annurev-fluid-121108-145519

DOI:10.1007/s12206-007-1201-8

DOI:10.1021/acs.langmuir.6b01490

DOI:10.1021/la063218t

DOI:10.1103/PhysRevLett.111.066101

DOI:10.1039/C5SM01125F [Cited within: 1]

DOI:10.1103/PhysRev.37.405 [Cited within: 1]

DOI:10.1103/PhysRev.38.2265 [Cited within: 1]

DOI:10.1088/0953-8984/23/28/284118 [Cited within: 1]

DOI:10.1088/1674-1056/24/2/020505 [Cited within: 1]

DOI:10.1103/PhysRevLett.116.066101 [Cited within: 5]

DOI:10.1088/1674-1056/ab8ac7 [Cited within: 2]

DOI:10.1038/s41598-018-20581-0 [Cited within: 1]

DOI:10.1021/acs.langmuir.8b01655 [Cited within: 3]

DOI:10.1021/acs.langmuir.9b02229 [Cited within: 2]

DOI:10.1021/acs.langmuir.7b01354 [Cited within: 2]

DOI:10.1088/1361-648X/aae1dc [Cited within: 1]

DOI:10.1088/0953-8984/27/8/085005 [Cited within: 1]

DOI:10.1038/nature10344 [Cited within: 2]

DOI:10.1021/acs.langmuir.8b00427 [Cited within: 1]

[Cited within: 1]

DOI:10.1021/la202077w [Cited within: 1]

DOI:10.1017/jfm.2015.312 [Cited within: 1]

DOI:10.1016/0021-9797(84)90245-5 [Cited within: 1]