HTML

--> --> -->Superheavy nuclei are produced through a fusion action in heavy ion collisions with different methods. One of these methods involves the concept of dinuclear system (DNS) model, which works well to describe the fusion in reactions producing superheavy nuclei [2-7]. At energies around the Coulomb barrier for heavy ion collisions, after mutual capture of colliding nuclei, a moleculelike nuclear configuration (so-called nuclear molecule or DNS) is probably to form [5-7]. At this step, nucleons are exchanged between two nuclei as far as the DNS evolves to the equilibrium. Before compound nucleus (CN) formation, owing to Coulomb repulsion, the DNS may separate again (approximately

A nuclear molecule or DNS consists of two touching nuclei that move within the internuclear distance with the transfer of nucleons. Consequently, this system consists of two main degrees of freedom: (1) the exchange of nucleons between the projectile and target nuclei, and (2) the relative motion between two nuclei, leading to fusion-fission and QF, respectively. QF and fusion-fission are severe obstacles to the formation of a superheavy nucleus. The principal difference between QF and fusion-fission is that a CN is not formed during the QF process [9-11].

Generally, heavy nuclei are produced in three stages: capture, fusion, and deexcitation. Studying each of these stages can help us understand and analyze the production of heavy nuclei.

In this study, we aimed to find an appropriate DNS for the formation of

It needs to be said that projectiles heavier than

This paper reviews the driving potential in the framework of the two-center shell model (TCSM) and the folding potential in Section II. The results are presented in Section III in the form of capture, fusion, and evaporation residue cross sections, and survival probability calculations. Finally, the conclusions drawn from our calculations are provided in Section IV.

A.Driving potential

The potential energy for heavy nuclear configuration plays a crucial role for the understanding of the evolution of the collision of nuclei. Thus, it is better to start with the driving potential. The potential energy surface that controls the evolution of a nuclear system in a multi-dimensional space is commonly called “driving potential” [23]. In other words, the driving potential includes a value of nucleus-nucleus potential corresponding to the minimum of its potential well.The potential energy depends on three parameters: (1) the mass asymmetry (

The potential energy of the separated nuclei is defined as the interaction energy of the colliding nuclei, which might be calculated using the double-folding method, proximity potential, or Bass model (for spherical nuclei). By crossing the fusion barrier, the further evolution of the system may be an adiabatic or diabatic process (owing to the relative movement speed of the two nuclei) [23, 24]. Using the code in Ref. [24], one can calculate the multi-dimensional diabatic (in the folding model framework) and adiabatic (in the TCSM framework) driving potentials. As seen in Fig. 1, diabatic and adiabatic processes must have the same potential before the two nuclei touch, but after touching, these processes exhibit quite different behavior. In the diabatic process, the two nuclei approach each other rapidly, and after contact, they try to penetrate each other, and the potential energy increases rapidly. In contrast, in the adiabatic process, the nuclei slowly approach each other, and the DNS has sufficient opportunity to change its configuration to hold the nuclear density and to keep the potential energy from exceeding a certain limit. In this study, we used the adiabatic process for potential driving after touching. Moreover, we considered the axially symmetric configurations.

Figure1. (color online) Potential energy as elongation function for the nuclear system formed by (a)

Figure1. (color online) Potential energy as elongation function for the nuclear system formed by (a) In Fig. 1, the TCSM is used in the form of an adiabatic process to consider the shell effect, and the folding potential is used in the form of a diabatic process to consider the effects of deformation and orientation. The underlying theory is detailed in Secs. IIB and IIC.

2

B.TCSM potential

The TCSM Hamiltonian in cylindrical coordinates is defined as the sum of potential and kinetic energies, comprising three terms: a two-center oscillator, spin-orbit, and $ {\hat{H}}_{\rm TCSM} = -\frac{{\hslash }^2}{2m_0}{\bf{\nabla}}^2+V\left(z,\rho \right)+V_{{LS}}\left({{r}},{{p}},{{s}}\right)+V_{{{L}}^{2}}\left({{r}},{{p}}\right), $  | (1) |

$ V\left(z,\rho{}\right) = \frac{1}{2m_0}\left\{\begin{array}{l}\left({\omega{}}_{z1}^2{z^{'}}^2+{\omega{}}_{\rho{}1}^2{\rho{}}^2\right),\qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad\;\;\; z<z_1 \\\left[{\omega{}}_{z1}^2{z^{'}}^2\left(1+c_1z^{'}+d_1{z^{'}}^2\right)+{\omega{}}_{\rho{}1}^2{\rho{}}^2\left(1+g_1{z^{'}}^2\right)\right],\qquad z_1<z<0 \\ \left[{\omega{}}_{z2}^2{z^{'}}^2\left(1+c_2z^{'}+d_2{z^{'}}^2\right)+{\omega{}}_{\rho{}2}^2{\rho{}}^2\left(1+g_2{z^{'}}^2\right)\right],\qquad 0<z<z_2 \\\left({\omega{}}_{z1}^2{z^{'}}^2+{\omega{}}_{\rho{}1}^2{\rho{}}^2\right),\qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad\qquad\;\;\; z>z_2\end{array}\right. $  | (2) |

$ z^{'} = \left\{\begin{array}{ll}z-z_1, & z<0 \\ z-z_2,& z>0\end{array}\right. $  | (3) |

$ V_{LS}\left({{{r}},{{p}},{{s}}}\right) = \left\{\begin{array}{l}\left\{-\dfrac{\hslash{}{\kappa{}}_1}{m_0{\omega{}}_{01}},\left({\bf{\nabla}}V\times{}{{p}}\right)\cdot{{s}}\right\},\ \ \ \ \ z<0 \\ \left\{-\dfrac{\hslash{}{\kappa{}}_2}{m_0{\omega{}}_{02}},\left({\bf{\nabla}}V\times{}{{p}}\right)\cdot {{s}}\right\},\ \ \ \ \ z>0\end{array}\right. $  | (4) |

$ V_{L^2}\left({{{r}},{{p}}}\right) = \left\{\begin{array}{l}-\dfrac{1}{2}\left\{{\kappa{}}_1{\mu{}}_1{\hslash{}\omega{}}_{01},{{{l}}^{\bf{2}}}\right\}+{\kappa{}}_1{\mu{}}_1{\hslash{}\omega{}}_{01}\dfrac{N_1\left(N_1+3\right)}{2}{\delta{}}_{if},\ \ \ \ \ z<0 \\ -\dfrac{1}{2}\left\{{\kappa{}}_2{\mu{}}_2{\hslash{}\omega{}}_{02},{{{l}}^{\bf{2}}}\right\}+{\kappa{}}_2{\mu{}}_2{\hslash{}\omega{}}_{02}\dfrac{N_2\left(N_2+3\right)}{2}{\delta{}}_{if},\ \ \ \ \ z>0\end{array}\right. $  | (5) |

The potential mentioned in Eqs. (1-5) refers to a single-particle potential. We used the TCSM for the calculation of the adiabatic potential energy of the nucleus-nucleus interaction that can be found in [24].

2

C.Folding potential

The double-folding model is one of the most common methods to determine the internuclear potential for heavy ion interaction that includes the sum of the effective interaction of the nucleon-nucleon. The interaction energy of two nuclei in the folding model is calculated as [23, 24, 31] $ V_{12}\left(r;{\delta }_1,\Omega _1,{\delta }_2,\Omega _2\right)=\int^{\ }_{V_1}{{\rho }_1\left({{r}}_1\right)}\int^{\ }_{V_2}{{\rho }_2\left({{r}}_2\right)v_{NN}\left({{r}}_{12}\right){\rm d}^3{{r}}_1{\rm d}^3{{r}}_2}, $  | (6) |

$ \rho \left({{r}}\right) = {\rho }_0{\left[1+\exp\left(\frac{r-R\left(\Omega _{{r}}\right)}{a}\right)\right]}^{-1}, $  | (7) |

Figure 2 shows the driving potentials as a function of the

Figure2. (color online) Driving potential as a one variable function (

Figure2. (color online) Driving potential as a one variable function (| Reaction |   | Mass asymmetry (   | Minimum potential energy/MeV | |

First   | Second   | |||

| 12.716 | 0.696 | 179.3 | 179.7 |

| 12.675 | 0.716 | 169.9 | 170.2 |

| 12.630 | 0.736 | 157.3 | 157.6 |

| 12.622 | 0.743 | 153.9 | 154.3 |

Table1.Minimum value of the driving potential (in the TCSM) as a function of

By using the code in Ref. [24], we show in Fig. 3 the driving potential as a function of the proton number of the DNS leading to an identical CN with A = 296 and Z = 119 (in contact point). This figure is equivalent to Fig. 2. It is clear from Figs. 2 and 3 that the amount of internal fusion barrier in the

Figure3. (color online) Driving potential calculated for the DNS leading to an identical CN with A = 296 and Z = 119 as a function of the proton number of the DNS formed by (a)

Figure3. (color online) Driving potential calculated for the DNS leading to an identical CN with A = 296 and Z = 119 as a function of the proton number of the DNS formed by (a) The landscape of the potential energy surface specifies the competition between complete fusion and QF during the evolution of the DNS [32]. For this purpose, the dependence of the potential energy on the polar orientation for each reaction was studied. In Fig. 4, this dependence on the orientation with the parameter R can be observed. This figure shows that the parameters of the fusion barriers strongly depend on the orientation of the nuclei during fusion [23, 25, 26]. According to this figure, the minimum and maximum energies occur at

Figure4. (color online) Dependence of the potential energy on mutual orientation in the reaction plane and R (distance between mass centers of colliding nuclei) in (a)

Figure4. (color online) Dependence of the potential energy on mutual orientation in the reaction plane and R (distance between mass centers of colliding nuclei) in (a) | Reaction | Minimum energy (  |

| 183.48 MeV (12.03  |

| 181.27 MeV (12.05  |

| 178.79 MeV (11.95  |

| 168.34 MeV (11.90  |

Table2.Minimum potential energy obtained from the reactions at

A.Capture cross section

In the fusion of superheavy ions, the CN formation probability after touching of two nuclei is less than unity due to the QF processes. In such systems, the cross section of fusion corresponds to the so-called “capture cross section”, which is defined as the QF cross section (without CN formation) plus the fusion cross section (CN formation). The total capture cross section is [3, 23, 25, 26] $ {\sigma }_{\rm cap}\left(E,l\right) = \pi { \lambda^{_{--}}}^2\mathop \sum \limits_{l = 0}^\infty {\left(2l+1\right)}T_l\left(E\right), $  | (8) |

$ T^{\rm HW}_l\left(B,E\right) = {\left(1+\exp\left(\frac{2\pi }{\hslash{\omega }_B\left(l\right)}\left[B+\frac{\hslash^2}{2\mu R^2_B\left(l\right)}l\left(l+1\right)-E\right]\right)\right)}^{-1}, $  | (9) |

$ T_l\left(E\right) = \int{F}\left(B\right)T_l^{HW}\left[B(\beta);E\right]{\rm d}B, $  | (10) |

$ F(B) = N.\exp{\left(-\left[\frac{B-B_{0}}{\Delta_B}\right]^{2}\right)}, $  | (11) |

For our studied reactions, which consist of a spherical projectile and statically deformed target, the penetration probability must be averaged on the deformation-dependent barrier height and the colliding nuclei orientations. The Coulomb barrier height depends on the dynamic deformation of the projectile. Therefore, the probability of penetration is as follows [24]:

$ T_l\left(E\right) = \int_0^{\pi{}}\frac{\sin{\theta{}}_2}{2}{\rm d}{\theta{}}_2\int{F}\left(B^{'}\right)T_l^{\rm HW}\left[B(\theta,\beta);E\right]{\rm d}B^{'}, $  | (12) |

$ B\left(\theta{},\beta{}\right) = B^{'}+\left[B\left(\theta{},0\right),B\left(0,0\right)\right],\ \ \ \ B^{'} = B\left(0,\beta{}\right). $  | (13) |

| reactions | critical angular momentum |

| 121 |

| 119 |

| 116 |

| 116 |

Table3.Amount of critical angular momentum used in the studied reactions.

Fig. 5 shows the calculated cross section of the fusion and capture. The difference between these cross sections is due to the absence of the CN in the QF process [9, 10].

Figure5. (color online) Fusion (solid curve) and capture (dashed curve) cross sections calculated for the analyzed reactions: (a)

Figure5. (color online) Fusion (solid curve) and capture (dashed curve) cross sections calculated for the analyzed reactions: (a) 2

B.Fusion cross section

The cross section of the CN (fusion) is calculated as [16] $ {\sigma }_{\rm fus}\left(E,l\right) = \frac{\pi {\hslash }^2}{2\mu E}\mathop \sum \limits_{l = 0}^\infty {\left(2l+1\right)}T_l\left(E\right)P_{\rm CN}, $  | (14) |

$ P_{\rm CN}\left(E,l\right) = \dfrac{\exp(-c(x_{\rm eff}-x_{\rm thr}))}{1+\exp\left(\dfrac{E^*_B-E^*_{\rm int}\left(l\right)}{\Delta}\right)}, $  | (15) |

According to Table 4, the maximum values for

| Reaction | Maximum capture cross section (  | Maximum fusion cross section (  |

| 855.234 mb (275  | 0.859 mb (265  |

| 861.806 mb (255  | 5.921 mb (260  |

| 954.991 mb (255  | 39.891 mb (255  |

| 1005.70 mb (245  | 200.349 mb (245  |

Table4.Maximum values for

2

C.Evaporation residue cross section

The formation cross section of the evaporation residue for heavy nuclei collisions is given as follows [39] $ {\sigma }_{\rm EvR}\left(E_{\rm c.m.}\right) = \mathop \sum \limits_{J = 0}^{{J_{\max}}} {{\sigma }_{\rm cap}\left(E_{\rm c.m.},J\right)P_{\rm CN}\left(E_{\rm c.m.},J\right)W_{\rm sur}\left(E_{\rm c.m.},J\right)}, $  | (16) |

The excitation energy of the formed compound nucleus is approximately

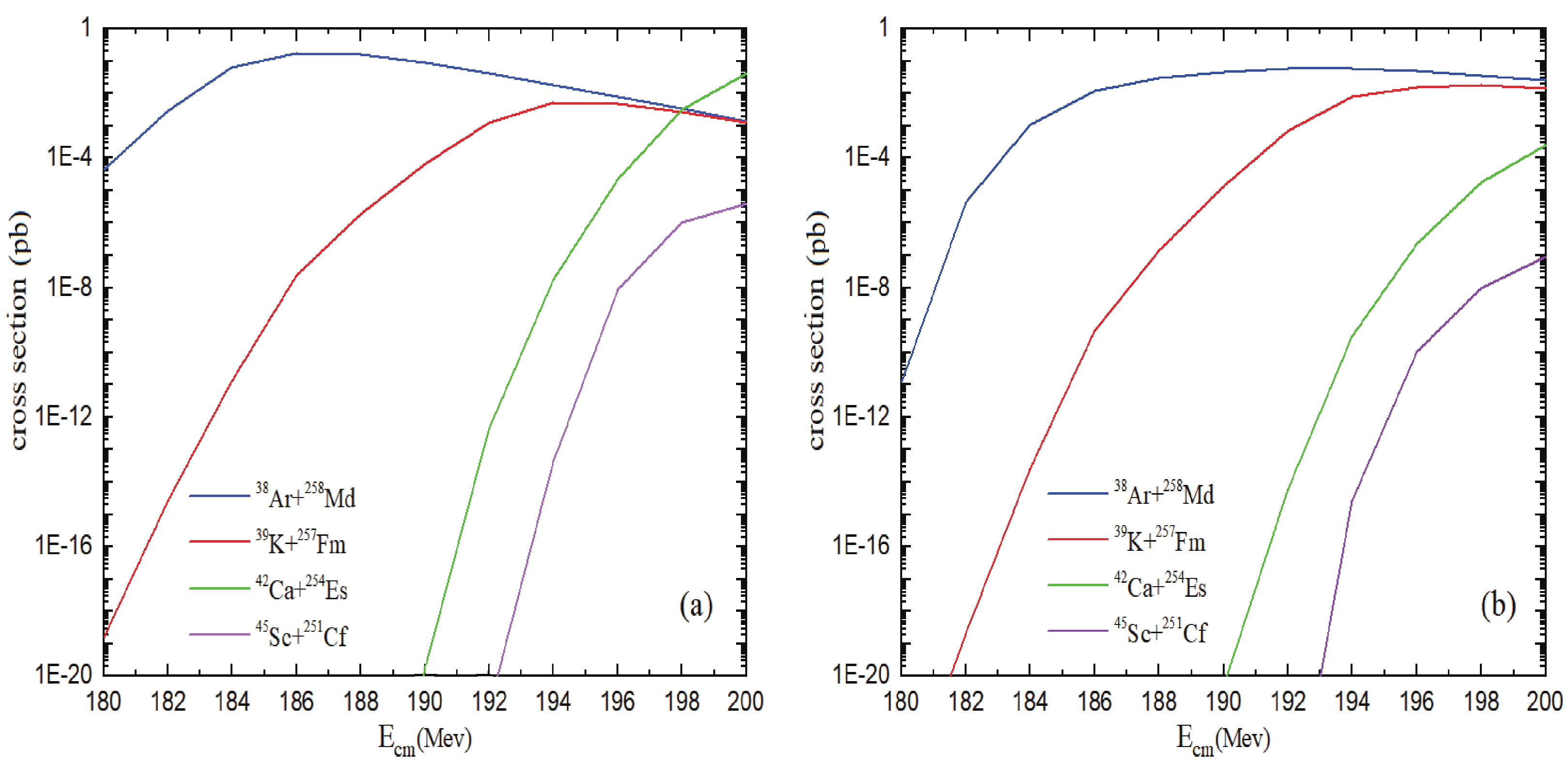

Figure6. (color online) (a) Cross sections of the evaporation residue calculated for the 3n channel and (b) for the 4n channel in the reactions.

Figure6. (color online) (a) Cross sections of the evaporation residue calculated for the 3n channel and (b) for the 4n channel in the reactions.2

D.Survival probability for the excited CN

For an excited CN, the probability to achieve a ground state with the emission of a neutron (or neutrons) is defined as “survival probability” and denoted by $ {\sigma}_{\rm surv}\left(E,l\right)=\pi { \lambda^{_{--}}}^2\mathop \sum \limits_{l = 0}^\infty {\left(2l+1\right)}T_l\left(E\right)P_{\rm CN}\left(E,l\right)\sum\limits_{xn,yp,z\alpha}W^{xn,yp,z\alpha}_{\rm surv}\left(E,l\right), $  | (17) |

$ W^{1n}_{\rm sur}(E_{\rm c.m.},J = 0) = \frac{\Gamma_n\left(E^*_{\rm CN}\right)}{\Gamma_f\left(E^*_{\rm CN}\right)} \\= \frac{4A^{{2}/{3}}\left(E^*_{\rm CN}-B_n\right)}{k\left(2{\left[a\left(E^*_{\rm CN}-B_f\right)\right]}^{{1}/{2}}-1\right)}\exp{\left[2a^{{1}/{2}}\left(\sqrt{E^*_{\rm CN}-B_n}-\sqrt{E^*_{\rm CN}-B_f}\right)\right]}, $  | (18) |

Previous studies showed that the probability of the survival is strongly proportional to the properties of the nuclear structure for the superheavy nuclei like deformation and level density [31]. We applied these properties in our calculations.

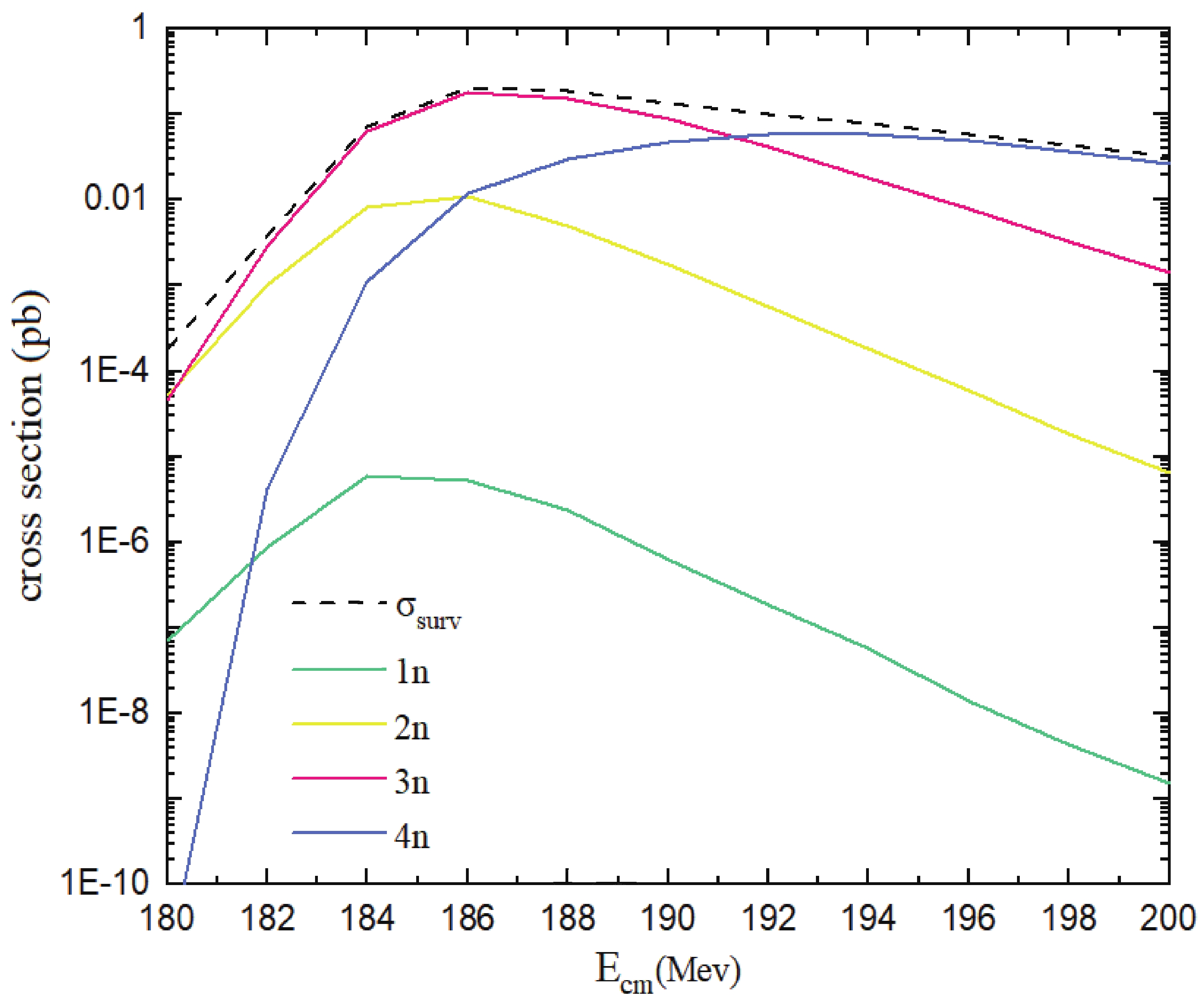

The results of calculation for

Figure7. (color online) Survival cross section (dashed curve) and cross section of the evaporation residue (color curves) calculated for the 1n-4n channels in the

Figure7. (color online) Survival cross section (dashed curve) and cross section of the evaporation residue (color curves) calculated for the 1n-4n channels in the For the reactions with a larger mass asymmetry parameter, the minimum potential value in the contact point is further reduced. Thus,

Although the maximum values for the capture and fusion cross sections are higher in the reaction