HTML

--> --> -->The present study aims to provide additional information on the nuclear structure of these neutron-rich odd-mass 151-161Pm and odd-odd 154,156Pm nuclei. The theoretical framework of the projected shell model (PSM) [16] will be used for this purpose. From the wave functions obtained in the PSM calculations, we obtain various observables, such as B(E2) and B(M1) transition probabilities, which can provide a deeper understanding of the structure of these Pm isotopes. Physical insights provided from this particular model have already proven useful for understanding A = 150 nuclei [17-22]. The organization of this paper is as follows: in Section 2, we briefly review the PSM. The results, including the yrast energy spectra and M1 and E2 transition probabilities, are presented and discussed in Sections 3 and 4 for odd-mass and odd-odd Pm isotopes, respectively. The main conclusions are summarized in Section 5.

The Hamiltonian used in the present work consists of a sum of schematic (quadrupole-quadrupole + monopole + quadrupole-pairing) forces that represent different kinds of characteristic correlations between active nucleons. The total Hamiltonian is of the form:

$\hat H = {\hat H_0}{\rm{ }} - {\rm{ }}\frac{1}{2}\chi \sum\limits_{\mu} {} \hat Q_{\mu} ^{{\dagger }}{\hat Q_{\mu} } - {G_M}{\hat P^{{\dagger }}}\hat P - {G_Q}\sum\limits_{\mu} {\hat P_{\mu} ^{{\dagger }}} {\hat P_{\mu} },$ | (1) |

This single-particle term is given by

${\hat H_0}{\rm{ = }}\sum\limits_{\alpha} {c_{\alpha} ^{\dagger} {E_{\alpha} }} {c_{\alpha} },$ | (2) |

${E_{\alpha} } = \hbar \omega \left[ {N - 2\kappa \hat l.\hat s - \kappa \mu \left( {{{\hat l}^2} - {{\left\langle {\hat l} \right\rangle }^2}} \right)} \right].$ | (3) |

The remaining terms in Eq. (1) are residual quadrupole-quadrupole, monopole, and quadrupole–pairing interactions, respectively. The operators appearing in Eq. (1) are defined as in Ref. [27], and the interaction strengths are determined as follows:

● The Q.Q interaction strength χ is adjusted by the self-consistent relation such that the input quadrupole deformation ε2 and that resulting from the HFB procedure agree with each other.

● All pairing interactions are assumed to occur between like nucleons (i.e., the isovector type). The monopole pairing strength, GM, first introduced by Dieterich et al. [28], is given by

● The quadrupole pairing strength, GQ, is assumed to be proportional to GM, and is generally set at approximately 1/5th of the monopole pairing constant, GM, allowing a ±10% variation to obtain the best representation of the experimental observations.

The next step is to diagonalize the Hamiltonian in the shell model space spanned by a selected set of projected multi-quasiparticle

${\rm{ }}\hat P_{MK}^I = \frac{{2I + 1}}{{8{\pi ^2}}}\int {{\rm d}\Omega D_{MK}^I} \left( \Omega \right)\hat R\left( \Omega \right).$ | (4) |

$\left| {{\phi _{\kappa} }} \right\rangle = \left\{ {a_{\pi} ^{\dagger} \left| 0 \right\rangle ,a_{\pi} ^{\dagger} a_{{\nu _1}}^{\dagger} a_{{\nu _2}}^{\dagger} \left| 0 \right\rangle } \right\},$ | (5) |

$\left| {{\phi _{\kappa} }} \right\rangle = \left\{ {{\rm{ }}a_{{\upsilon _i}}^{{\dagger }}a_{{\pi _j}}^{{\dagger }}\left| 0 \right\rangle } \right\},$ | (6) |

Finally, the many-body wave function, which is a superposition of projected (angular momentum) multi-quasiparticle states, can be written as

$\left| {\Psi _{IM}^{\sigma} } \right\rangle = \sum\limits_{K\kappa } {f_{{\kappa _{}}}^{\sigma} \hat P_{MK}^I} \left| {{\phi _{\kappa} }} \right\rangle, $ | (7) |

$\sum\limits_{\kappa '} {\left\{ {{\rm{ }}H_{\kappa {\rm{ }}\kappa '}^I - E_{\sigma ,I}^{}{\rm{ }}N_{\kappa {\rm{ }}\kappa '}^{}} \right\}} {\rm{ }}f_{\kappa '}^{\sigma ,I} = 0,$ | (8) |

$\sum\limits_{\kappa \kappa '} {f_{\kappa} ^{\sigma ,I}{N_{\kappa \kappa '}}} f_{\kappa '}^{\sigma ',I'} = {\delta _{\sigma \sigma '}}{\delta _{I{\rm{ }}I'}},$ | (9) |

$H_{\kappa {\rm{ }}\kappa '{\rm{ }}}^I = \left\langle {\mathop \phi \nolimits_{\kappa} } \right|\hat H{\rm{ }}{\hat P_{{K_{\kappa} }{{K'}_{\kappa '}}}}\left| {\mathop \phi \nolimits_{\kappa '} } \right\rangle \;\;\;{\rm{and}}\;\;\; \mathop N\nolimits_{\kappa {\rm{ }}\kappa '{\rm{ }}}^I = \left\langle {\mathop \phi \nolimits_{\kappa} } \right|\hat P_{{K_{\kappa {\rm{ }}}}K'{}_{\kappa '}}^{\rm{I}}\left| {\mathop \phi \nolimits_{\kappa '} } \right\rangle. $ | (10) |

${E_{\kappa} }(I) = \frac{{\langle {\varphi _{\kappa} }|\hat H\hat P_{K{\rm{ }}K}^I|{\varphi _{\kappa} }\rangle }}{{\langle {\varphi _{\kappa} }|\hat P_{K{\rm{ }}K}^I|{\varphi _{\kappa} }\rangle }} = \frac{{H_{\kappa \kappa }^I}}{{N_{\kappa \kappa }^I}},$ | (11) |

2

2.1.Input parameters used in the present calculations

The Shell model space in the present work is truncated by fitting the energy window around the neutron and proton Fermi surfaces at 4.50 MeV for the 1–quasiparticle and 9.50 MeV for the 3–quasiparticle basis states. The value of the quadrupole deformation parameter, ε2, is set as ~0.3 for all the nuclei under study, which is in agreement with the values given in Refs. [2-4]. In our meanfield Nilsson potential, which provides the optimal deformed basis, the hexadecapole deformation, ε4, has also been included and is set as ~ -0.090. The values of G1 and G2 are taken as 21.00 MeV and 10.70 MeV, respectively. The value of GQ in our work is set to be 0.16 times GM. The Nilsson parameters κ and μ are set according to the values given in Ref. [24]. In addition, in the present calculations, the three major shell single-particle con?gurations consist of N = 3, 4, 5 for protons and N = 4, 5, 6 for neutrons.3.1.Energy levels

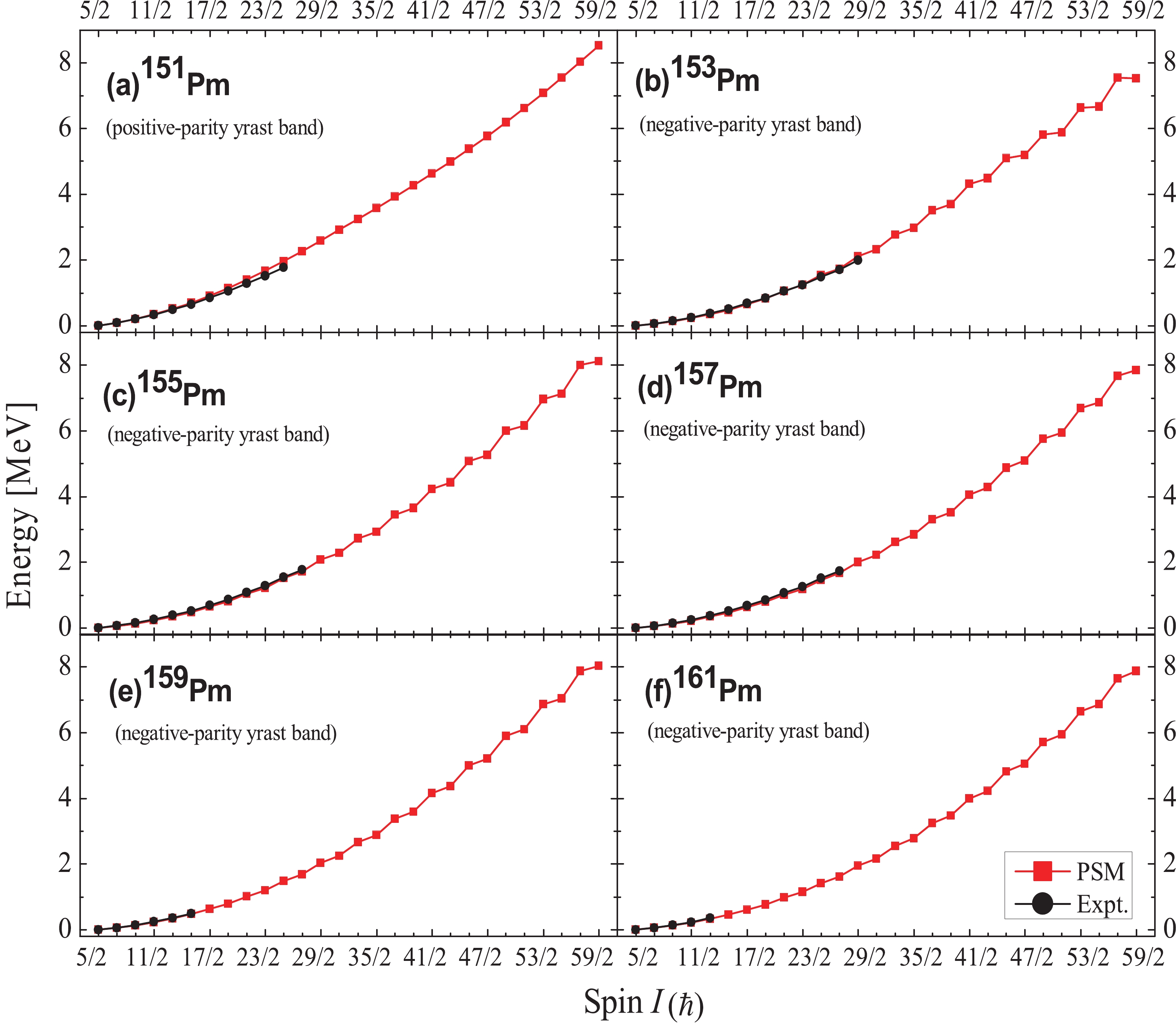

For the present study, the experimental data for the odd-mass 151-161Pm isotopes are taken from Refs. [3-5] and the NNDC database [30, 31]. The ground-state band in 151Pm [30] is reported to have a band head with spin and parity, Kπ = 5/2+, whereas all other odd-mass Pm isotopes under study have a ground-state band with a band head at Kπ = 5/2?. Note that the experimental data is sparse for these odd mass Pm isotopes. The maximum reported spin is 31/2? for 151Pm [30], 29/2? for 153Pm [5], 27/2? for 155, 157Pm [5, 31], 15/2? for 159Pm [4], and in case of 161Pm, the experimental data is available only up to a spin of 13/2? [4]. However, through our PSM calculations, we have been able to extend the yrast level scheme and obtained the higher energy levels up to a spin of 59/2? for all of these isotopes. Note that the ground-state bands of all of these odd-mass Pm isotopes, except for 151Pm, are negative parity bands, while 151Pm has a positive-parity band. However, a negative parity band in addition to the ground-state positive-parity band has also been reported in 151Pm, which is built on Kπ = 5/2? at an excitation energy of 0.117 MeV with respect to the ground state.Our PSM calculations successfully reproduced the band-head spin and parity for all of these isotopes. The PSM energies for the ground-state yrast bands under study are plotted against the spin for the 151-161Pm isotopes in Figs. 1(a-f), whereas the excited negative-parity band of 151Pm is presented in Fig. 1(g). The available experimental data are also presented in the same figures for comparison. It is clear from the figures that the calculated PSM data reproduced the available experimental data with a satisfactory degree of agreement, where the maximum gap between the experimental and calculated energy levels is only ~0.124 MeV in the case of 153Pm for the 29/2? state, which proves the efficiency of the set of input parameters used in the PSM Hamiltonian to give a comprehensive description of the nuclear structure in this mass region.

Figure1(a-f). (color online) Calculated yrast band energies (PSM) in comparison with the available experimental data (Expt.) for 151-161Pm. Experimental data are taken from Refs. (a)151Pm [30], (b) 153Pm [5], (c) 155Pm [31], (d) 157Pm [5], (e) 159Pm [4] and (f) 161Pm [4].

Figure1(a-f). (color online) Calculated yrast band energies (PSM) in comparison with the available experimental data (Expt.) for 151-161Pm. Experimental data are taken from Refs. (a)151Pm [30], (b) 153Pm [5], (c) 155Pm [31], (d) 157Pm [5], (e) 159Pm [4] and (f) 161Pm [4].It is worth mentioning here that the nuclei under study are located at the boundary of the octupole deformed lanthanide region [32, 33]. In fact, many research groups [10-12] have pointed out the presence of octupole deformation in 151Pm, whereas the possibility of the presence of a reflection asymmetric shape at N = 92 has also been reported in 153Pm [34]. However, Bhattacharyya et al. [5] in their recently documented work stated that the observed band structures of odd-A Pm isotopes do not show any indication of the presence of octupole deformation beyond N = 90. As the present PSM calculations have been performed using an axially symmetric Hamiltonian, the extent of agreement between the PSM results and the experimental data supports the findings of Bhattacharya et al. One more interesting feature of these nuclei is that the energy levels of the negative-parity bands for all Pm isotopes considered in the present work are very close to each other, indicating that the addition of a pair of high-j neutrons does not significantly affect the deformation of these nuclei. However, the addition of a pair of neutrons to 151Pm changes the Kπ of the yrast band from 5/2+ in 151Pm to 5/2? in 153Pm. This provides an idea regarding how the addition of neutrons in the high-j orbitals affects the energies of the proton orbitals under the same deformation.

2

3.2.Quasi-particle structure of 151-161Pm isotopes

33.2.1.Band diagrams

A band diagram serves as a very useful tool for analyzing the PSM results. These are quite informative and can help unravel the intrinsic quasi-particle structures of the observed bands. Band diagrams are the plots of unperturbed energies before configuration mixing. In a band diagram, the rotational behavior of each configuration, as well as its relative energy compared with other configurations, can be easily visualized. In the present calculations, our configuration space is built by thirty-eight quasiparticle (qp) bands, out of which there are six 1-qp (1-quasiproton) bands and thirty-two 3-qp (1-quasiproton plus a pair of 2- Figure2. (color online) Band diagrams for 151-161Pm. Yrast band (black squares) is also shown.

Figure2. (color online) Band diagrams for 151-161Pm. Yrast band (black squares) is also shown.It is clearly visible from these figures that the 1-quasiproton band with the configuration 1πh11/2[5/2], |K|=5/2 is the dominant band affecting the formation of the ground-state yrast band in the odd-mass 153-161Pm isotopes and the negative-parity yrast band in 151Pm. The ground-state yrast band in 151Pm (which is a positive-parity band) is the band having the configuration 1πg9/2[5/2], K=5/2 originating from the πg7/2 orbital, which gives rise to the yrast spectra in the low- and mid-spin range.

The observation made in the present work is in agreement with the experimental results reported for these isotopes, which suggests that the yrast ground band in 151Pm is 5/2+ based on the 5/2+[413] configuration [12], whereas the non-yrast structure (negative-parity band) in 151Pm is reported to be based on a 5/2?[532] Nilsson configuration originating from the πh11/2 orbital. Furthermore, in the case of 153Pm, the yrast ground-state band built on K = 5/2? is also known to be constituted from the 5/2?[532] Nilsson orbital [35], which originates from the deformation driving πh11/2 orbital. Bhattacharyya et al. [5] suggested the same 5/2[532] configuration assignment for the observed negative-parity bands in 155,157Pm. A similar band structure to that of 153,155Pm is predicted for 159,161Pm by Yokoyama et al. [4]. This is very well reproduced by the present PSM calculations.

The other important thing that should be noted here is the very late occurrence or absence of band crossing in most of these isotopes. Their ground-state band is mostly dominated by the 1-qp bands. For the negative-parity band in 151Pm, the 1-qp band is crossed by a 3-qp band having the configuration 1πh11/2[5/2]+ 2νi13/2[?3/2,5/2], |K|= 7/2 at a spin of 45/2?, whereas the crossing is predicted at a spin of 49/2? in 153Pm. For 155Pm, the band crossing is further delayed and occurs at aspin of 53/2?, where the 1-qp 1πh11/2[5/2], |K|=5/2 band is crossed by a 3-qp 1πh11/2[1/2]+ 2νi13/2[5/2, ?7/2], |K|= ?1/2 band. Moving to higher-N/Z Pm isotopes, no band crossing is observed up to a spin of 59/2?. There may be a crossing occurring at higher spins than 59/2?, but we restrict our study to a spin of 59/2? only, as the experimental data have not been reported for such higher spins.

For the positive-parity ground state band in 151Pm, the 1-quasiproton band, 1πg9/2[5/2], |K|=5/2, is crossed by the 3-qp band identified to have the configuration 1πg9/2[5/2]+ 2νi13/2[-3/2,5/2], |K|= 7/2 at a spin of 43/2+, whereafter its interaction with another 3-qp band with |K| = 1/2 gives rise to the yrast spectra for the rest of the spins. The band structure of the ground-state band of 151Pm is quite different from the band structures of the other odd-mass Pm isotopes under study. One possible reason may be the presence of octupole correlation resulting from he closely lying 5/2?[532] and 5/2+[413] bands that originate from the g7/2 and h11/2 proton orbitals. However, our study is restricted to axial symmetry only, so we cannot comment on this in detail. Also, in the low-spin range, odd-mass 153-161Pm has almost the same band structure, which explains the presence of levels of nearly the same energies in their ground-state bands.

3

3.2.2.Wave functions

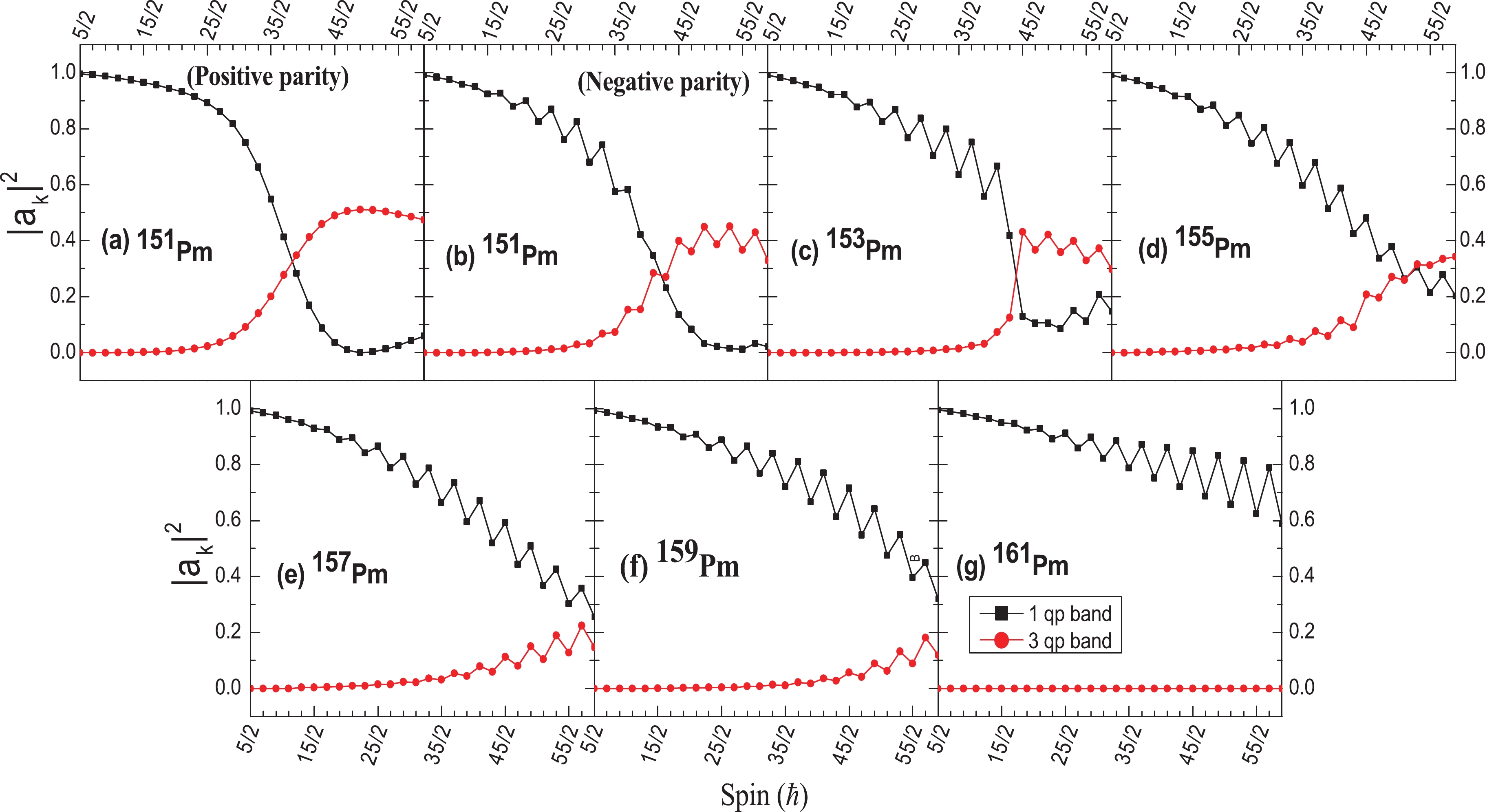

In the PSM approach, the eigenvalues of energy, along with the amplitude of wave functions, are obtained by diagonalization of the total Hamiltonian. Schematic analysis of the probability amplitude of various n-qp configurations for odd-mass 151-161Pm isotopes was performed in the present work. The average probability amplitudes of 1-qp and 3-qp configurations were plotted versus spin, and the results are displayed in Figs. 3(a-g) respectively. Figure3. (color online) Probability amplitude of various projected K-configurations in the wave functions of the yrast bands for 151-161Pm.

Figure3. (color online) Probability amplitude of various projected K-configurations in the wave functions of the yrast bands for 151-161Pm.For these Z=61 isotopes, it is clear from the probability amplitude plots that the lower spins of the ground-state bands arise solely from the contribution of the 1-qp configurations, whereas the contribution from the 3-qp configurations at higher spins for 151,153, & 155Pm isotopes is also predicted by the present PSM calculations. For the 157-161Pm isotopes, the dominance of the 1-qp configurations over the whole spin range, up to 59/2?, is established from the present analysis. Also, the absence of crossing between the 1-qp and 3-qp bands in these 157,159,161Pm isotopes, as depicted by the band diagrams [Fig. 2(e-g)], is supported by analysis of the amplitude of the wave functions of these qp configurations.

2

3.3.Energy staggering in odd-mass 151-161Pm isotopes

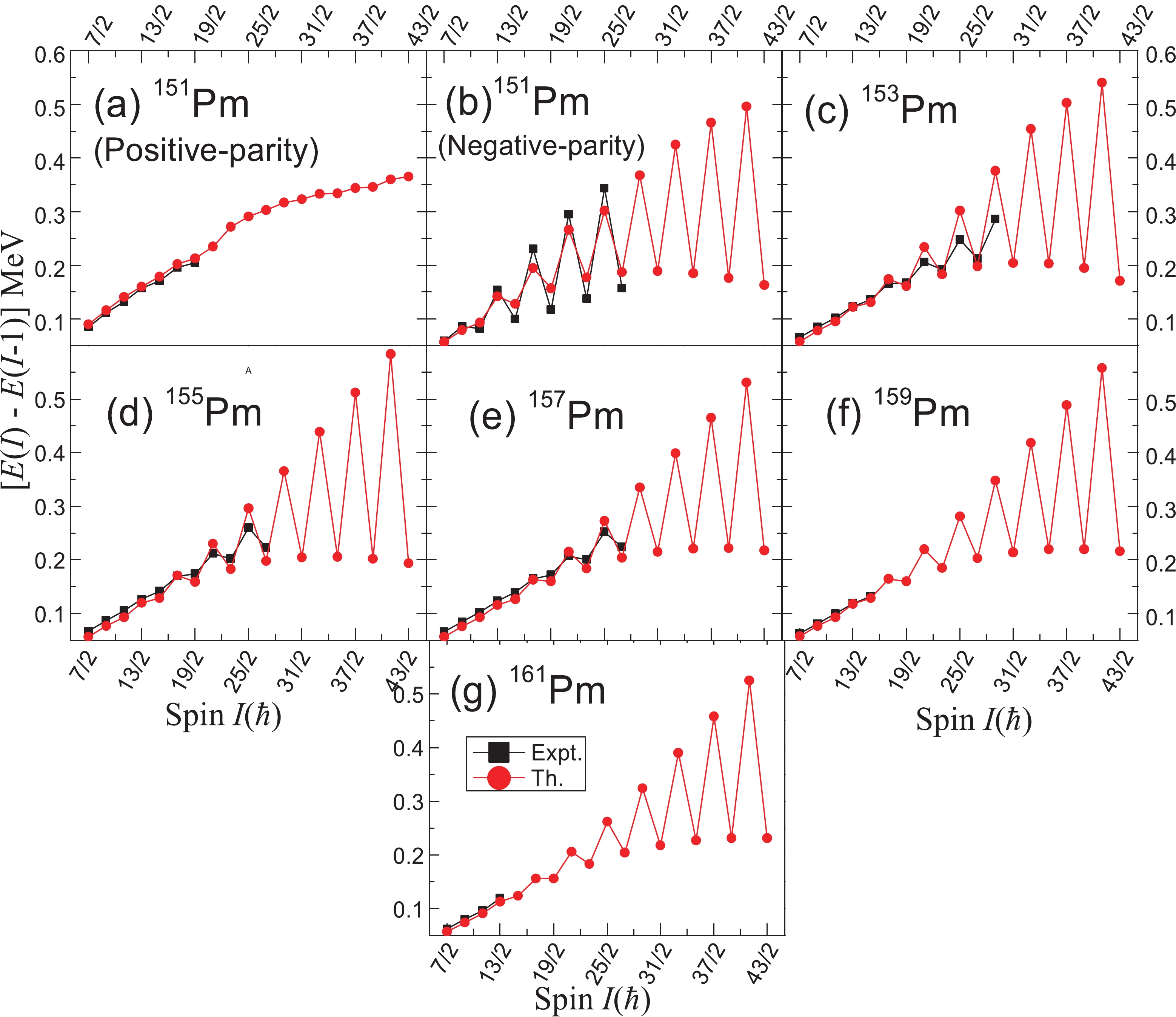

The transition energies [E(I) ?E(I ? 1)] of the states in the yrast bands of the odd-A Pm isotopes under study are presented in Figs. 4(a-g) as a function of spin I. It is evident from the figures that staggering in the energies of odd-even spin states is present for all of these nuclei. In the case of 151Pm, the positive-parity ground-state band shows small shifts in the energies of odd-even states, whereas the energy staggering is more prominent in the negative-parity band (1πh11/2[5/2]) of 151Pm corresponding to the 5/2?[532] orbital. The amount of staggering further increases in this case as we move toward the high-spin domain. The rest of the Pm isotopes (odd-A 153-161Pm) show a similar trend of variation of the quantity [E(I) ?E(I ? 1)] versus spin for their ground bands, where in the low-spin range, the extent of staggering is small, becoming moderate in the mid-range spin range; then, in the high-spin domain, this odd-even energy difference becomes quite large, with a maximum difference of ~0.4 MeV. However, no sign of inversion of the staggering pattern is found in the present analysis for any of these isotopes. The staggering pattern shown by the yrast bands in these nuclei are very much in accordance with the staggering pattern shown by the probability amplitude of the wave functions [Figs. 3(a-g)]. Figure4. (color online) Plots of the quantity E(I) –E(I?1) as a function of spin I for the yrast bands in odd-mass 151-161Pm isotopes.

Figure4. (color online) Plots of the quantity E(I) –E(I?1) as a function of spin I for the yrast bands in odd-mass 151-161Pm isotopes.2

3.4.Reduced transition probabilities, B(E2) and B(M1)

The electromagnetic transition probabilities calculated using PSM contain detailed information on the nuclear wave function, which can aid in enhancing our knowledge of the nuclear structure of the nuclei under study. The reduced electric quadrupole transition probability B(E2) from an initial state (Ii = I) to a final state (If = I - 2) is given by [36] $B(E2, I \to I - 2) = \frac{{{e^2}}}{{2I + 1}}{\left| {{\rm{ }}\left\langle {{\psi ^{I - 2}}} \right|{\rm{ }}\left| {{\rm{ }}{{\hat Q}_2}{\rm{ }}} \right|{\rm{ }}\left| {{\psi ^I}} \right\rangle {\rm{ }}} \right|^2}.$ |

${\hat Q_{2{\rm{ }}\nu }}{\rm{ }} = {\rm{ }}e_{\nu} ^{{\rm{eff}}}\sqrt {\frac{5}{{16\pi }}} Q_{\nu} ^2,\;\;\;\;{\hat Q_{2{\rm{ }}\pi }}{\rm{ }} = {\rm{ }}e_{\pi} ^{{\rm{eff}}}\sqrt {\frac{5}{{16\pi }}} Q_{\pi} ^2.$ | (12) |

The reduced magnetic transition probability can also be calculated using PSM wave functions. Magnetic dipole transition strengths are sensitive to the single-particle attributes of the nuclear wave function. The reduced magnetic dipole transition probability B(M1) is computed as

$B\left( {M1,I \to I - 1} \right) = \frac{{\mu _N^2}}{{2I + 1}}{\rm{ }}{\left| {{\rm{ }}\left\langle {{\psi ^{I - 1}}} \right.\left| {{\rm{ }}\left| {{{\hat M}_1}} \right|{\rm{ }}} \right|{\rm{ }}\left. {{\psi ^I}} \right\rangle {\rm{ }}} \right|^2},$  | (13) |

$\hat {\rm M}_{{{\rm{ }}1}}^{\tau} = g_l^{\tau} {\hat j^{\tau} } + \left( {g_s^{\tau} - g_l^{\tau} } \right){\rm{ }}{\hat s^{\tau} },$ | (14) |

$g_{l}^{\pi }=1,g_{l}^{\nu }=0,g_{s}^{\pi }=5.586,\ \ {\rm{and}}\ \ g_{s}^{\nu }=-3.826.$  |

The reduced matrix element of an operator

$\begin{split} \left\langle {{\psi ^{{I_f}}}} \right.\left\| {{\rm{ }}{{\hat O}_L}{\rm{ }}} \right\|\left. {{\rm{ }}{\psi ^{{I_i}}}} \right\rangle = \sum\limits_{{\kappa _i},{\kappa _f}} {f_{{I_i}{\kappa _i}}^{{\sigma _i}}} f_{{I_f}{\kappa _f}}^{{\sigma _f}}\sum\limits_{{M_i},{M_f},M} {{\rm{ }}( - 1)} {{\rm{ }}^{{I_f} - {M_f}}}{\rm{ }}\end{split}$  |

$\begin{split}&\quad\quad\times\left( {{\rm{ }}\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} {{{\rm{I}}_{\rm{f}}}} \\ {{\rm{ - }}{{\rm{M}}_{\rm{f}}}} \end{array}{\rm{ }}\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} {\rm{L}} \\ {\rm{M}} \end{array}{\rm{ }}\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} {{{\rm{I}}_{\rm{i}}}} \\ {{{\rm{M}}_{\rm{i}}}} \end{array}} \right)\\&\quad\quad\times \left\langle {{\phi _{{\rm{ }}{\kappa _f}}}} \right|\hat P_{{K_{{\kappa _f}}}{M_f}}^{{I_f}}{\hat O_{L{\rm{ }}M}}\hat P_{{K_{\kappa {}_i}}{M_i}}^{I_i^{}}\left| {{\phi _{{\kappa _{\rm{i}}}}}} \right\rangle\end{split}.$  | (15) |

| 151Pm | 153Pm | 155Pm | |||||||

| Transition | B(E2↓)(Positive-parity Yrast) | Transition | B(E2↓)(Negative-parity) | Transition | B(E2↓) | Transition | B(E2↓) | ||

| 9/2+ →5/2+ | 3.50 | 9/2ˉ →5/2ˉ | 0.306 | 9/2ˉ →5/2ˉ | 3.03 | 9/2ˉ →5/2ˉ | 0.096 | ||

| 11/2+→7/2+ | 0.788 | 11/2ˉ→7/2ˉ | 1.35E-4 | 11/2ˉ→7/2ˉ | 0.67 | 11/2ˉ→7/2ˉ | 0.341 | ||

| 13/2+→9/2+ | 0.0909 | 13/2ˉ→9/2ˉ | 0.0962 | 13/2ˉ→9/2ˉ | 0.0732 | 13/2ˉ→9/2ˉ | 0.563 | ||

| 15/2+→11/2+ | 0.0057 | 15/2ˉ→11/2ˉ | 0.266 | 15/2ˉ→11/2ˉ | 0.0066 | 15/2ˉ→11/2ˉ | 0.724 | ||

| 17/2+→13/2+ | 0.11 | 17/2ˉ→13/2ˉ | 0.431 | 17/2ˉ→13/2ˉ | 0.102 | 17/2ˉ→13/2ˉ | 0.858 | ||

| 19/2+→15/2+ | 0.265 | 19/2ˉ→15/2ˉ | 0.571 | 19/2ˉ→15/2ˉ | 0.239 | 19/2ˉ→15/2ˉ | 0.941 | ||

| 21/2+→17/2+ | 0.422 | 21/2ˉ→17/2ˉ | 0.687 | 21/2ˉ→17/2ˉ | 0.376 | 21/2ˉ→17/2ˉ | 1.02 | ||

| 23/2+ →19/2+ | 0.565 | 23/2ˉ →19/2ˉ | 0.78 | 23/2ˉ →19/2ˉ | 0.499 | 23/2ˉ →19/2ˉ | 1.06 | ||

| 25/2+→ 21/2+ | 0.690 | 25/2ˉ→ 21/2ˉ | 0.858 | 25/2ˉ→ 21/2ˉ | 0.606 | 25/2ˉ→ 21/2ˉ | 1.13 | ||

| 27/2+→ 23/2+ | 0.797 | 27/2ˉ→ 23/2ˉ | 0.919 | 27/2ˉ→ 23/2ˉ | 0.698 | 27/2ˉ→ 23/2ˉ | 1.139 | ||

| 29/2+→ 25/2+ | 0.889 | 29/2ˉ→ 25/2ˉ | 0.973 | 29/2ˉ→ 25/2ˉ | 0.776 | 29/2ˉ→ 25/2ˉ | 1.19 | ||

Table1.Calculated B(E2↓) values (in e2b2) for odd-A 151-161Pm isotopes.

| 151Pm | 153Pm | 155Pm | |||||||

| Transition | B(M1↓) (Positive-parity Yrast) | Transition | B(M1↓) (Negative-parity) | Transition | B(M1↓) | Transition | B(M1↓) | ||

| 7/2+→5/2+ | 0.052 | 7/2ˉ→5/2ˉ | 5.84E-6 | 7/2ˉ→5/2ˉ | 0.082 | 7/2ˉ→5/2ˉ | 0.0853 | ||

| 9/2+ →7/2+ | 0.000021 | 9/2ˉ →7/2ˉ | 0.124 | 9/2ˉ →7/2ˉ | 1.1E-4 | 9/2ˉ →7/2ˉ | 0.123 | ||

| 11/2+→9/2+ | 0.151 | 11/2ˉ→9/2ˉ | 0.189 | 11/2ˉ→9/2ˉ | 0.0075 | 11/2ˉ→9/2ˉ | 0.142 | ||

| 13/2+→11/2+ | 0.244 | 13/2ˉ→11/2ˉ | 0.227 | 13/2ˉ→11/2ˉ | 0.012 | 13/2ˉ→11/2ˉ | 0.154 | ||

| 15/2+→13/2+ | 0.305 | 15/2ˉ→13/2ˉ | 0.25 | 15/2ˉ→13/2ˉ | 0.015 | 15/2ˉ→13/2ˉ | 0.16 | ||

| 17/2+→15/2+ | 0.348 | 17/2ˉ→15/2ˉ | 0.265 | 17/2ˉ→15/2ˉ | 0.017 | 17/2ˉ→15/2ˉ | 0.166 | ||

| 19/2+→17/2+ | 0.379 | 19/2ˉ→17/2ˉ | 0.274 | 19/2ˉ→17/2ˉ | 0.0185 | 19/2ˉ→17/2ˉ | 0.167 | ||

| 21/2+→19/2+ | 0.403 | 21/2ˉ→19/2ˉ | 0.28 | 21/2ˉ→19/2ˉ | 0.0196 | 21/2ˉ→19/2ˉ | 0.171 | ||

| 23/2+→21/2+ | 0.421 | 23/2ˉ→21/2ˉ | 0.282 | 23/2ˉ→21/2ˉ | 0.0205 | 23/2ˉ→21/2ˉ | 0.17 | ||

| 25/2+ →23/2+ | 0.436 | 25/2ˉ →23/2ˉ | 0.284 | 25/2ˉ →23/2ˉ | 0.0213 | 25/2ˉ →23/2ˉ | 0.174 | ||

| 27/2+→25/2+ | 0.445 | 27/2ˉ→25/2ˉ | 0.282 | 27/2ˉ→25/2ˉ | 0.0219 | 27/2ˉ→25/2ˉ | 0.171 | ||

| 29/2+→27/2+ | 0.454 | 29/2ˉ→27/2ˉ | 0.2826 | 29/2ˉ→27/2ˉ | 0.0226 | 29/2ˉ→27/2ˉ | 0.176 | ||

Table2.Calculated B(M1↓) values (in

Prior to this work, no information had been reported on experimental as well as theoretical fronts regarding the reduced transition probabilities for these nuclei. Through the present calculations, we have been able to obtain the data concerning reduced transition probabilities for the yrast energy states up to a spin of 59/2. However, in Tables 1 and 2, we have provided results up to a spin of 29/2 only. Regarding the B(E2) transition probabilities, the PSM predicts that the quadrupole electric transition probabilities for these isotopes tend to decrease first and then increase gradually, possibly because of the decrease in the pairing correlations at smaller angular momentum. Conversely, the B(M1) transition probabilities show a similar increasing pattern for all of these isotopes. These values are obtained from the PSM wave functions and depend on the band structure of the nuclei. Here, a general trend for the B(E2) and B(M1) transition probabilities has been predicted by calculation for these isotopes. Although we would like to wait for some experimental data to be reported in the near future to make a final comment on this tendency and on the efficacy of our model for describing the nuclear structure properties of these rare earth nuclei, still, the data obtained in the present calculations can serve as a good base for future experimental as well as theoretical studies.

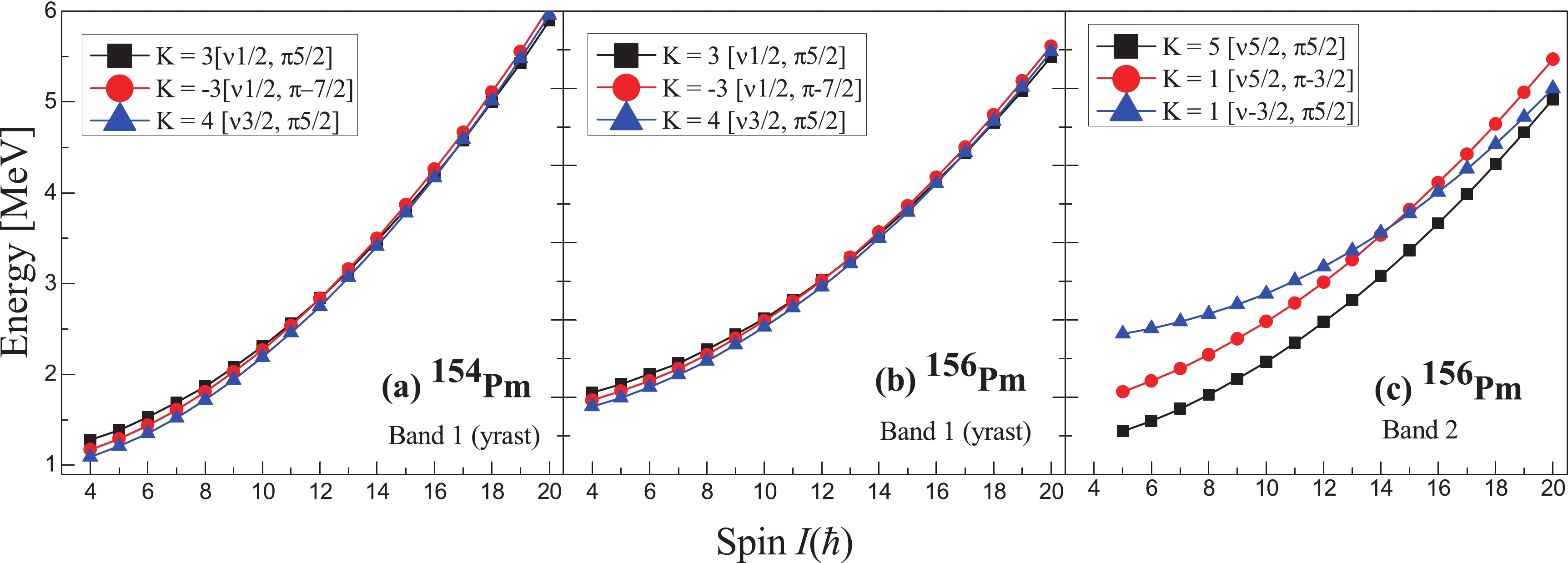

In the present work, we attempted to further understand the structure of these two odd-odd isotopes of Pm with A=154 and 156. Through our PSM calculations, we have been able to reproduce the bandhead spins and parities of the ground-state bands (lowest bands) in 154,156Pm as recommended by Liu et al. [3]. Additionally, one more band, ‘Band2’ of 156Pm with higher excitation energy than the ground-state band, was also obtained in the calculations. The results are presented in Fig. 5, where comparison of the PSM results with the experimental level schemes of these isotopes taken from Ref. [5] shows a good degree of agreement.

Figure5. (color online) PSM data on yrast bands of 154,156Pm in comparison with the experimental data [3]. A side band, 'Band 2' of 156Pm, is also presented.

Figure5. (color online) PSM data on yrast bands of 154,156Pm in comparison with the experimental data [3]. A side band, 'Band 2' of 156Pm, is also presented.The band diagrams of 154,156Pm are presented in Fig. 6. In the diagrams for these odd-odd isotopes, the projected energies are shown for 2-quasiparticle configurations (with K = Kν ± Kπ). Careful analysis of the band diagrams of 154,156Pm reveals that the yrast bands of both these isotopes have composite structures because of the mixing of three very closely lying bands. In the case of 154Pm, there are three 2-qp bands with bandheads K = 3, -3, and 4 lying very close to each other with an energy gap of ~0.5 MeV; these interact with each other to give rise to the yrast band in this nucleus. However, it is the band with configuration |K| = 4[ν3/2, π5/2] (neutron from the 3/2?[521] orbital and proton from 5/2?[532] orbital) that dominates the contribution toward the yrast band, thereby assigning the configuration |K| = 4[ν3/2, π5/2] to the ground-state band. A very similar band diagram is obtained for 156Pm, where the same configuration (|K| = 4[ν3/2, π5/2]) for the yrast ground-state band as that of 154Pm is predicted by the PSM calculations. Further, for the excited band of 156Pm, the main contribution comes from the |K| = 5[ν5/2, π5/2] band; thus, this configuration is assigned to the excited band of the 156Pm where the quasineutron band arises from the 5/2+[642] neutron orbit and the quasiproton band comes from the 5/2+[413] orbital. The configurations assigned to these 2-qp bands in the present work are found to be in accordance with the work of Liu et al. [3]. The information on the transition probabilities, B(M1) and B(E2), has also been extracted for these odd-odd nuclei, and the results are presented in Tables 3 and 4. This is the first time that such detailed data have been reported for these properties of odd-odd Pm isotopes, making this subject appropriate for further experimental verification.

Figure6. (color online) Band diagrams for A=154 and 156 Pm isotopes.

Figure6. (color online) Band diagrams for A=154 and 156 Pm isotopes.| Transition | B(E2↓) | ||

| 154Pm | 156Pm | ||

| Band 1 | Band 1 | Band 2 | |

| 6+ → 4+ | 1.21 | 1.24 | |

| 7+ → 5+ | 0.969 | 1.01 | 1.57 |

| 8+ → 6+ | 0.742 | 0.785 | 1.46 |

| 9+ → 7+ | 0.55 | 0.598 | 1.27 |

| 10+ →8+ | 0.359 | 0.411 | 1.08 |

| 11+→ 9+ | 0.247 | 0.291 | 0.917 |

| 12+ → 10+ | 0.137 | 0.172 | 0.774 |

| 13+ → 11+ | 0.089 | 0.111 | 0.653 |

| 14+ → 12+ | 0.052 | 0.0679 | 0.55 |

| 15+ → 13+ | 0.0344 | 0.042 | 0.461 |

| 16+ → 14+ | 0.023 | 0.029 | 0.387 |

| 17+ → 15+ | 0.0159 | 0.0189 | 0.323 |

| 18+ → 16+ | 0.0118 | 0.0148 | 0.271 |

| 19+ → 17+ | 0.0086 | 3.5E-4 | 0.224 |

| 20+ →18+ | 0.00696 | 1.47E-4 | 0.189 |

Table3.Calculated B(E2↓) values (in e2b2) for 154,156Pm isotopes

| Transition | B(M1↓) | ||

| 154Pm | 156Pm | ||

| Band 1 | Band 1 | Band 2 | |

| 5+ → 4+ | 0.0378 | 0.0442 | |

| 6+ → 5+ | 0.1733 | 0.179 | 0.194 |

| 7+ → 6+ | 0.259 | 0.275 | 0.307 |

| 8+ → 7+ | 0.437 | 0.444 | 0.378 |

| 9+ → 8+ | 0.342 | 0.378 | 0.424 |

| 10+ →9+ | 0.542 | 0.579 | 0.455 |

| 11+→ 10+ | 0.205 | 0.257 | 0.476 |

| 12+ → 11+ | 0.44 | 0.508 | 0.491 |

| 13+ → 12+ | 0.0579 | 0.0855 | 0.501 |

| 14+ → 13+ | 0.3 | 0.359 | 0.509 |

| 15+ → 14+ | 0.0106 | 0.0176 | 0.515 |

| 16+ → 15+ | 0.2 | 0.2392 | 0.519 |

| 17+ → 16+ | 0.0014 | 0.00245 | 0.522 |

| 18+ → 17+ | 0.136 | 0.156 | 0.524 |

| 19+ → 18+ | 2E-4 | 1.979E-5 | 0.526 |

| 20+ →19+ | 0.0937 | 2E-4 | 0.527 |

Table4.Calculated B(M1↓) values (in

The level schemes of the odd-mass 151-161Pm nuclei were obtained up to a spin of 59/2 in this work. The late occurrence of the band crossing between the 1-qp and the 3-qp band was observed for 151,153,155Pm, whereas no crossing was found to occur for the rest of the odd-mass Pm isotopes. Moreover, the yrast band in 157,159,161Pm was found to have only 1-qp characteristics up to the calculated spin of 59/2? with the configuration assignment of 1πh11/2[5/2], |K|=5/2. For the odd-odd 154,156Pm nuclei, PSM calculations helped to understand their structure in some detail. The previously assigned configurations of one 2-qp band (π5/2?[532]

The present calculations also endorse the absence of octupole correlations in these nuclei. Furthermore, signature-splitting is present in the yrast energy states of these nuclei in middle- and higher-spin ranges, but signature inversion is not found to occur up to the calculated values of spin. The data regarding the transition probabilities for all these nuclei under study were reported for the first time in this work. As no prior information is available for these properties of the Pm isotopes under study, the results are promising for future experimental verification.

Figure1(g). (color online) Calculated negative-parity band (PSM) in comparison with the available experimental data (Expt.) for 151Pm.

Figure1(g). (color online) Calculated negative-parity band (PSM) in comparison with the available experimental data (Expt.) for 151Pm.