HTML

--> --> -->The investigation of the QCD phase diagram for finite baryon and nonzero isospin densities has attracted considerable attention [8, 16-19]. The main reason is that the dense hadronic matter is isotopically asymmetric in heavy-ion collision experiments [20, 21]. The interior of compact stars is also expected to be isospin asymmetric [22]. A large class of effective theories, such as the chiral perturbation theory [8, 16], the Nambu–Jona-Lasinio (NJL) type models [23-27], linear sigma models [28], the Polyakov-Quark-Meson models [29, 30], the Dyson-Schwinger equations [31] and functional renormalization group methods [32, 33], have been used to explore the alignment of the vacuum expectation value (VEV) and the matter phase structure.

The study of QCD matter in external electromagnetic (EM) environment [34-40] has become of interest since the charge separation along the magnetic field was observed in non-central heavy-ion collisions at the Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider (RHIC) [41]. A background EM field exists in various physical systems, such as in compact stars [42], the early Universe [43] and at RHIC and the Large Hadron Collider [41, 44, 45]. The EM field excites charged particles in both the hadronic and quark-gluon plasma (QGP) phases, offering a unique opportunity for exploring the QCD vacuum structure and the thermodynamics of strongly interacting matter. Several approaches have been used to understand the phenomena of magnetic catalysis at low temperature, and of the inverse magnetic catalysis near

As a consequence, there is a good reason to study the behavior of diquarks in electromagnetized dense baryon matter, as the EM field acts on all charged collective modes, and the diquarks can be treated as elementary states of QCD matter at high baryon density [7, 9]. If only the QCD interactions are considered, the axial isospin current is anomaly free. The EM chiral anomaly arises when quarks couple to the electromagnetic field. The corresponding current is given by

$ \partial_{\mu}j_{5}^{\,\mu 3} = -\frac{e^{2}}{16\pi^{2}} \varepsilon^{ \alpha \beta\mu\nu}F_{ \alpha \beta}F_{\mu\nu}\cdot {\rm tr} \left[\tau_{3}Q^{2} \right], $  | (1) |

In order to determine the properties of diquarks in EM fields, we compute in this work the QCD phase diagram in the plane of baryon and axial isospin chemical potentials in two-color QCD, which consists of the two-color gauge group with two Dirac flavors in the fundamental representation. This model dynamically generates quasi-particles in terms of sigmas, pions and baryons (diquarks). The details of the model are given in Sec. 2. In Sec. 3, we derive the underlying effective Lagrangian. Using the static low-energy effective

$\begin{split} {\cal L}_{ {\rm NJL}} = &\bar{\psi} \left( {\rm i} \gamma^{\mu} \partial_{\mu}+\mu \gamma_{0}+\nu_{5} \gamma_{0} \gamma_{5}\tau_{3}-m_{0} \right)\psi\\&+ {\cal L}_{\bar{q}q}+ {\cal L}_{qq}+({\rm{color}} \;{\rm{triplet}} \;{\rm{terms}}), \end{split} $  | (2) |

$ {\cal L}_{\bar{q}q} = \frac{G}{2} \left[(\bar{\psi}\psi)^2+(\bar{\psi} {\rm i} \gamma_{5}\vec{\tau}\psi)^2 \right], $  | (3) |

$\begin{split} {\cal L}_{qq} =& \frac{H}{2}(\bar{\psi} {\rm i} \gamma_{5}\tau_{2}t_{2}C\bar{\psi}^{T})({\psi}^{T}C {\rm i} \gamma_{5}\tau_{2}t_{2}{\psi})\\&-\frac{H}{4}(\bar{\psi} \gamma_{3}\tau_{1}t_{2}C\bar{\psi}^{T})({\psi}^{T}C \gamma_{3}\tau_{1}t_{2}{\psi}), \end{split}$  | (4) |

Since

In [56, 75], the authors showed that the QCD vacuum makes a chiral rotation from the scalar

$ \psi = \frac{1}{{\sqrt 2 }}\left( {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} q\\ {C{{\bar q}^T}} \end{array}} \right),\;\;\;\bar \psi = \frac{1}{{\sqrt 2 }}\left( {\bar q,{q^T}C} \right), $  | (5) |

$ \Omega_{\rm{eff}} = \frac{1}{2}\bar{\psi} {\cal S}^{-1} \left(p;\pi_{3}, \Delta,d \right)\psi-\frac{\pi_{3}^2+| \Delta|^2+|d|^2}{4G}. $  | (6) |

$ {S^{ - 1}}(p) = \left( {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}}\!\!\!\! {{\not\!\! p} \!-\! M \!+ \!{\gamma _0}\mu + {\gamma _0}{\gamma _5}{\tau _3}{\nu _5}}&{\tilde \Delta }\\ { - {{\tilde \Delta }^\dagger }}&\!\!\!\!{{\not\!\! p}\! - \!{M^T}\! - \!{\gamma _0}\mu \!+\! {\gamma _0}{\gamma _5}{\tau _3}{\nu _5}} \end{array}}\!\!\!\! \right), $  | (7) |

The fundamental representation of the group

$ \Psi = \left( {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} {{\psi _L}}\\ {{{\tilde \psi }_R}} \end{array}} \right),\;\;\;{\Psi ^\dagger } = \left( {\psi _L^\dagger ,\tilde \psi _R^\dagger } \right),$  | (8) |

Using the above expression, the standard kinetic part of the Euclidean

$ {\cal L}_{ {\rm kin}} = \Psi^{\dagger} {\rm i} \sigma^{\mu}D_{\mu}\Psi, $  | (9) |

$ {\cal L}_{ {\rm mass}} = \frac{m_{0}}{2} \left(\Psi^{T} {\rm i} \sigma_{2}SE_{4}\Psi-\Psi^{*T} {\rm i} \sigma_{2}SE_{4}\Psi^{*} \right), $  | (10) |

$ {E_4} = \left( {\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} 0&{{\tau _0}}\\ { - {\tau _0}}&0 \end{array}} \right).$  | (11) |

$ S_{a} = \frac{1}{2\sqrt{2}} \left({\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} \tau_{a}&0\\ 0&-\tau_{a}^{T} \end{array}} \right),\quad {\rm for }\; a = 0,1,2,3; $  | (12) |

$ S_{a} = \frac{1}{2\sqrt{2}} \left({\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} 0& B_{a}\\ B_{a}^{\dagger}&0 \end{array}} \right),\quad {\rm for }\; a = 4,\cdots,9\ , $  | (13) |

$ X_{i} = \frac{1}{2\sqrt{2}} \left({\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} \tau_{i}&0\\ 0&\tau_{i}^{T} \end{array}} \right),\quad {\rm for }\; i = 1,2,3; $  | (14) |

$ X_{i} = \frac{1}{2\sqrt{2}} \left({\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} 0& D_{i}\\ D_{i}^{\dagger}&0 \end{array}} \right),\quad {\rm for }\; i = 4,5 \ , $  | (15) |

Employing the above representation, the conventional baryon Lagrangian term

$ B_{0} = - \gamma_{0}E_{4} = \left({\begin{array}{*{20}{c}} \tau_{0}& 0\\ 0& -\tau_{0} \end{array}} \right). $  | (16) |

For finite isospin density, applying the gauge transformation [7, 8]

$ \Psi\to V\,\Psi, \quad V = \exp \left( {\rm i} \theta^{i}X_{i} \right)\quad {\rm for}\; X_{i}\in {SU}(4)/ { Sp}(2), $  | (17) |

$ {\cal L}_{\chi {\rm PT}} = \frac{f_{\pi}^{2}}{4} {\rm Tr} \left(D_{\mu} \Sigma^{\dagger} \right) \left(D_{\mu} \Sigma \right)-c {\rm Tr}{ \left( \Sigma^{\dagger}+ \Sigma \right)}, $  | (18) |

$ \begin{array}{l}\;\;\; D_{\mu} \Sigma = \partial_{\mu} \Sigma+ \left(I_{\mu} \Sigma+ \Sigma I_{\mu}^{T} \right) \\ D_{\mu} \Sigma^{\dagger} = \partial_{\mu} \Sigma^{\dagger}- \left( \Sigma^{\dagger}I_{\mu}+I_{\mu}^{T} \Sigma^{\dagger} \right). \end{array} $  | (19) |

$ {\rm Tr} \left(I_{\mu}^{T} \Sigma^{\dagger}I_{\mu} \Sigma \right), \qquad{\rm and}\qquad {\rm Tr} \left(I_{\mu}I_{\mu} \right), $  | (20) |

$ {\cal L}_{\chi {\rm PT}} = {\cal L}_{\pi_{i}}\sim \nu^{2} {\rm Tr} \left(I_{0}^{T}\phi_{i}^{\dagger}I_{0}\phi_{i} \right) = \nu^{2}\, {{\rm{Diag}}} \left(\tau_{3}\tau_{i}^{T}\tau_{3}\tau_{i}^{T},\tau_{3}\tau_{i}\tau_{3}\tau_{i} \right), $  | (21) |

At finite baryon chemical potential

$\begin{split} {\cal L}_{\chi {\rm PT}} =& {\cal L}_{ \Delta, \Delta^{*}}\sim \mu^{2} {\rm Tr} \left(B_{0}^{T}\Phi_{i}^{\dagger}B_{0}\Phi_{i} \right) \\=& -\mu^{2}\, {{\rm{Diag}}} \left(\tau_{0}t_{i}\tau_{0}t_{i}^{\dagger},\tau_{0}t_{i}^{\dagger}\tau_{0}t_{i} \right) . \end{split}$  | (22) |

When the axial isospin chemical potential

$ \begin{split} {\cal L}_{\chi {\rm PT}} =& {\cal L}_{\pi_{i}}\sim\nu_{5}^{2} {\rm Tr} \left(I_{5}^{T}\phi_{i}^{\dagger}I_{5}\phi_{i} \right) \\=& -\nu_{5}^{2}\, {{\rm{Diag}}} \left(\tau_{3}\tau_{i}^{T}\tau_{3}\tau_{i}^{T},\tau_{3}\tau_{i}\tau_{3}\tau_{i} \right), \end{split} $  | (23) |

Moreover, in the high baryon density limit, where flavor symmetric diquarks spontaneously form a condensate, the remaining

$\begin{split} {\cal L}_{\chi {\rm PT}} =& {\cal L}_{ \Delta,d}\sim \nu_{5}^{2} {\rm Tr} \left(I_{5}^{T}\Phi_{i}^{\dagger}I_{5}\Phi_{i} \right) \\=& \nu_{5}^{2}\, {{\rm{Diag}}} \left(\tau_{3}t_{i}\tau_{3}t_{i}^{\dagger},\tau_{3}t_{i}^{\dagger}\tau_{3}t_{i} \right) ,\end{split} $  | (24) |

We use the single Dirac component

$\begin{split}\Omega(T,\mu,\nu_{5}) = &\frac{T}{2V}\ln\det {\cal S}^{-1} \left( {\rm i} \omega_{n},p;\pi_{3}, \Delta,d \right)+\frac{\pi_{3}^{2}+ \Delta^{2}+d^{2}}{4G} \\ =& -T\sum_{n}\int\frac{ {\rm d}^{3}p}{(2\pi)^{3}}\frac{1}{2} {\rm Tr}\ln \left(\frac{1}{T} {\cal S}^{-1} \left( {\rm i} \omega_{n},p;\pi_{3}, \Delta,d \right) \right) \\&+\frac{\pi_{3}^{2}+ \Delta^{2}+d^{2}}{4G}, \end{split} $  | (25) |

From the above expression, one obtains three gap equations by minimizing the thermodynamic potential with respect to the mean values of the three meson and diquark fields [11, 78]

$ \frac{ \partial \Omega}{ \partial\pi_{3}} = 0,\quad \frac{ \partial \Omega}{ \partial \Delta} = 0,\quad \frac{ \partial \Omega}{ \partial d} = 0. $  | (26) |

$ \frac{1}{2} {\rm Tr}\ln \left(\frac{1}{T} {\cal S}^{-1} \left( {\rm i} \omega_{n},p;\pi_{3}, \Delta,d \right) \right) = \sum_{i = 1}^{8}\ln \left(\frac{ \omega_{n}^{2}+E_{i}^{2}}{T^{2}} \right). $  | (27) |

$ E_{i}(\vec{p}\,) = \pm\sqrt{d^{2}+\vec{p}^{\,2}+ \left(\mu\pm\nu_{5} \right)^{2}\pm 2\sqrt{d^{2}p_{z}^{2}+\vec{p}^{\,2} \left(\mu\pm\nu_{5} \right)^{2}}}. $  | (28) |

Employing the two-color NJL model, the thermodynamical potential becomes

$ \begin{split} \Omega(T,\mu,\nu_{5}) =& -\sum_{i = 1}^{8}\int\frac{ {\rm d}^{3}p}{(2\pi)^{3}} \left[E_{i}(\vec{p}\,)\, \theta \left( \Lambda^{2}-\vec{p}\,^{2} \right)\right.\\&\left.+2T\ln \left(1+ {\rm e}^{-\frac{E_{i}(\vec{p}\,)}{T}} \right) \right]+\frac{\pi_{3}^{2}+ \Delta^{2}+d^{2}}{4G}, \end{split}$  | (29) |

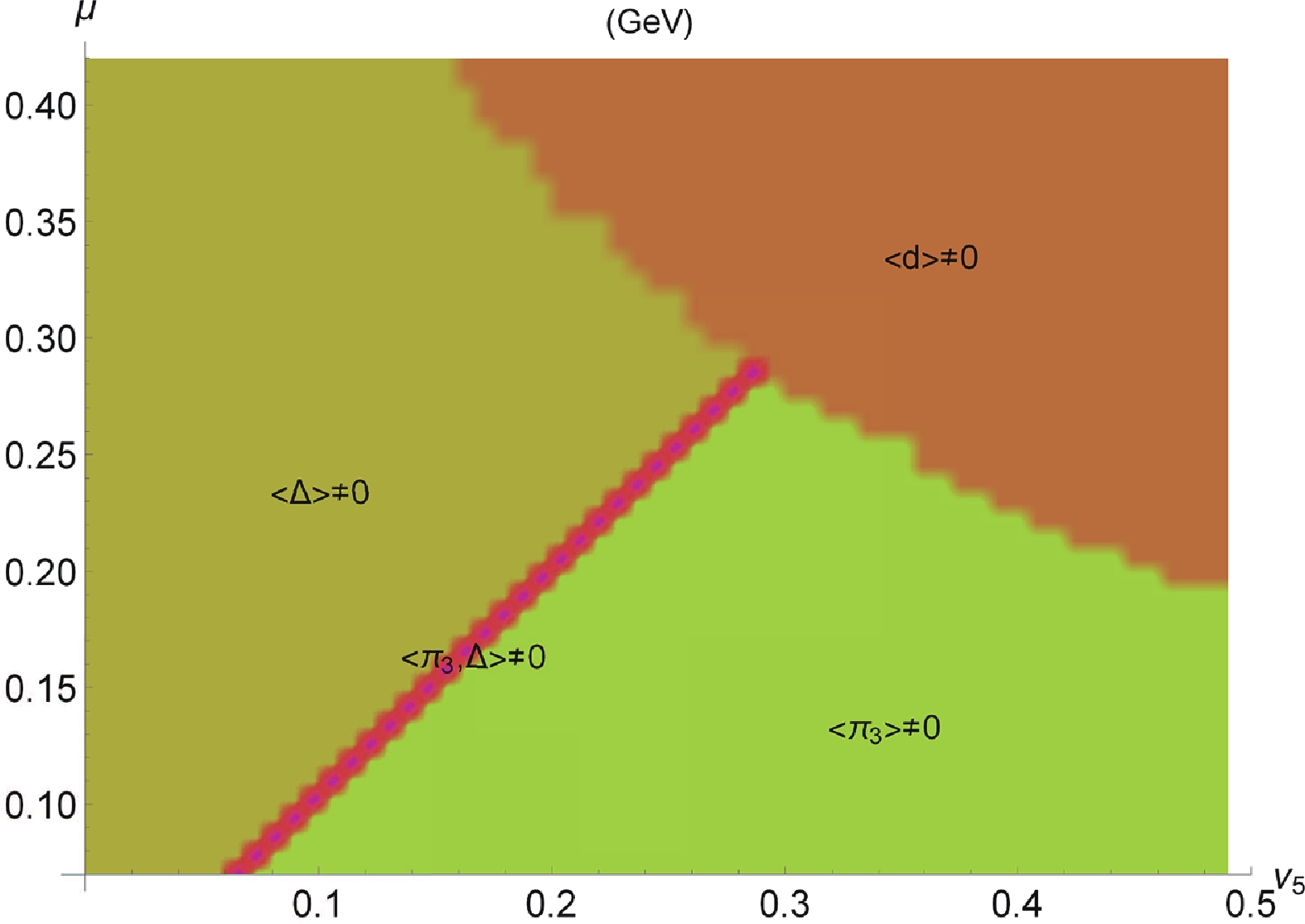

Figure1. (color online) Phase diagram of the two-color QCD with two fundamental quarks in the

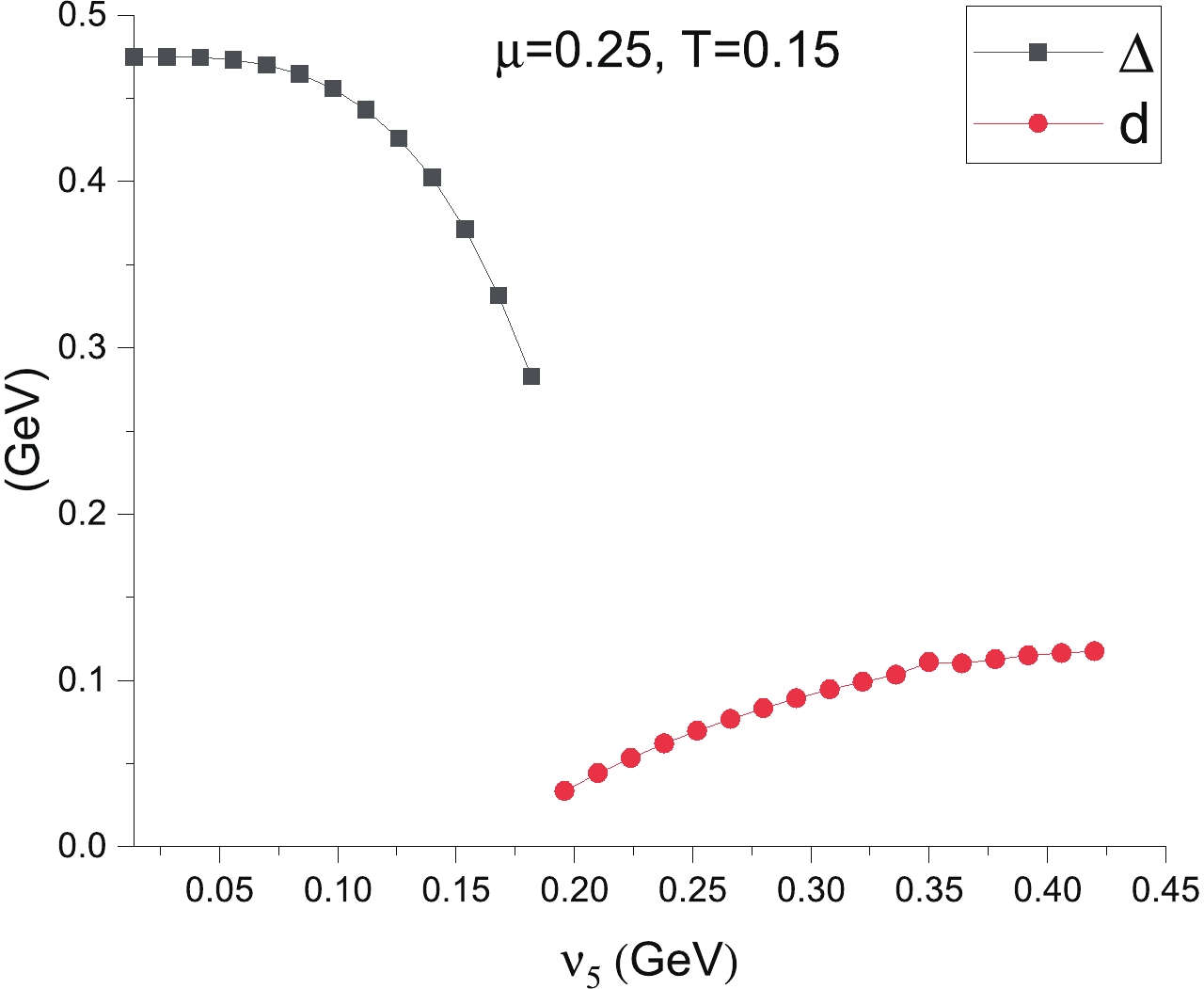

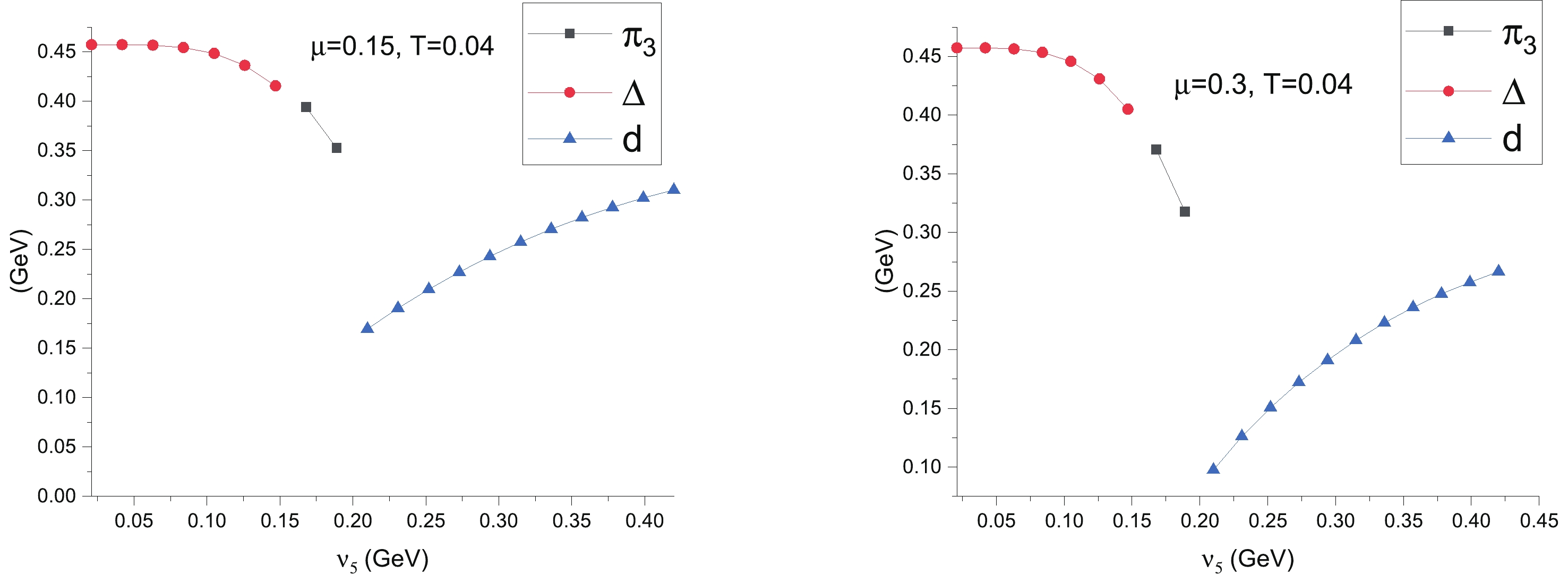

Figure1. (color online) Phase diagram of the two-color QCD with two fundamental quarks in the The VEVs of the three condensates are shown as a function of the axial isospin chemical potential and/or temperature in Figs. 2, 3 and 4. These plots demonstrate that the gap of the spin one color superconductor is smaller than the chiral condensate, as revealed in the early studies of the

Figure2. (color online) Scalar diquark condensate

Figure2. (color online) Scalar diquark condensate  Figure3. (color online) Scalar diquark condensate

Figure3. (color online) Scalar diquark condensate  Figure4. (color online) Neutral pion condensate

Figure4. (color online) Neutral pion condensate Following previous works on anisotopic dense quark matter [4, 7, 8], the chiral rotation in

Assuming that the condensates involve only real

In our simplified model, the back reactions on the electric blind fields have not been taken into account. The coupling of the quark sector to the Polyakov loop is not included and therefore there is no (de)confinement effect [81-83]. Furthermore, a first principles calculation could be pursued by the Dyson-Schwinger equations and/or functional renormalization group approach. As this study was devoted to the properties of the axial isotopically asymmetric dense QCD matter, it could be verified by lattice simulations of the two-color QCD applying similar strategies for finite baryon and isospin chemical potentials.

An application of our analysis to heavy-ion collisions, where strong anti-parallel electric and magnetic fields are produced above and below the reaction plane, is suggested. In addition, we observed that the axial vector diquark condensate develops as a physical ground state in the phase diagram. Its equation-of-state, thermodynamic behavior and transport coefficients, especially its emissivity, could be studied in low-temperature/high-density heavy-ion collision experiments at several worldwide facilities. It also gives reason for further investigations in the case of compact stars.

To summarize, this work explores the phenomenology of the QCD-like matter in different extreme conditions. The study of the two-color QCD serves as a first step towards realistic QCD matter. The subject of a future investigation will be to extend this work to the

I thank M. Huang, K. Xu and M. Ruggieri for discussions and the comments from T. Schaefer.