,1,2,3,*

,1,2,3,*Pareiasaur and dicynodont fossils from upper Permian of Shouyang, Shanxi, China

YI Jian1,2,3, LIU Jun ,1,2,3,*

,1,2,3,*收稿日期:2019-08-9网络出版日期:2020-01-20

| 基金资助: |

Corresponding authors: *liujun@ivpp.ac.cn

Received:2019-08-9Online:2020-01-20

摘要

中国二叠纪四足类的研究由来已久,在新疆和内蒙古大青山发现了大量二齿兽类(Dicynodontia)化石,而在华北地层区则以锯齿龙类(Pareiasauria)化石为主,还没有发现二齿兽类。近年来,在山西寿阳二叠系中发现了产自上石盒子组中的锯齿龙类和产自孙家沟组中的二齿兽类化石。根据髂骨的形态特征,相较于二叠石千峰龙(Shihtienfenia permica), 新的锯齿龙类化石与多齿河南龙(Honania complicidentata)更相似。这表明济源动物群(河南龙组合带)可能在山西的上石盒子组中也有分布。根据头骨的特征,新二齿兽类化石属于隐齿兽目(Cryptodontia), 可能是其中的某个支系在中国的第一个代表。

关键词:

Abstract

Chinese Permian tetrapods have been studied for decades. Many dicynodont fossils were reported from Xinjiang and Nei Mongol, only several pareiasaur species were reported in Shanxi (North China), where no dicynodonts have been reported. In this paper, a pareiasaur specimen and a dicynodont specimen are reported from the Shangshihezi Formation and the Sunjiagou Formation of Shouyang, Shanxi respectively. The pareiasaur specimen is more similar to Honania than Shihtienfenia based on iliac morphology. This suggests that the element of the Jiyuan Fauna (Honania Assemblage Zone) also occurs in the Shangshihezi Formation of Shanxi. The dicynodont fossil, an incomplete skull, is referred to Cryptodontia, and is probably the first representative of a new subclade within Cryptodontia in China.

Keywords:

PDF (2099KB)元数据多维度评价相关文章导出EndNote|Ris|Bibtex收藏本文

本文引用格式

伊剑, 刘俊. 山西寿阳二叠系上部的锯齿龙类和二齿兽类化石. 古脊椎动物学报[J], 2020, 58(1): 16-23 DOI:10.19615/j.cnki.1000-3118.191121

YI Jian, LIU Jun.

Chinese Permian tetrapods have been known for decades. Dicynodon sinkianensis, now revised as Jimusaria sinkianensis, from the Guodikeng Formation of Xinjiang was the first to be reported (Yuan and Young, 1934; Sun, 1963). Later, dicynodonts were reported from the Quanzijie Formation and Wutonggou Formation of Xinjiang as well (Sun, 1978; Li and Liu, 2015). In North Qilian area, a dicynodont species, Dicynodon sunanensis, was described from the Sunan Formation (Li et al., 2000) and revised as Turfanodon bogdaensis or T. sunanensis subsequently (Kammerer et al., 2011; Li and Liu, 2015). However, no pareiasaur fossils have been reported from Xinjiang.

In Nei Mongol, many tetrapod specimens have been discovered and at least four dicynodont species and one pareiasaur species are present in the Daqingshan area (Shiguai of Baotou, Nei Mongol) (Liu and Bever, 2018; Liu, 2019). In North China, the upper Permian Sunjiagou Formation and Shangshihezi (Upper Shihhotse) Formation have the widest exposure of all contemporaneous deposits, and their distributions are adjacent to the Daqingshan area. Many pareiasaur species have been named for the specimens from the above formations (Benton, 2016), however, no dicynodonts have been reported (Li and Liu, 2015). The only known tetrapod locality in the Shangshihezi Formation (Huagedaliang of Jiyuan, Henan) is dominated by the pareiasaur Honania (Young, 1979; Liu et al., 2014).

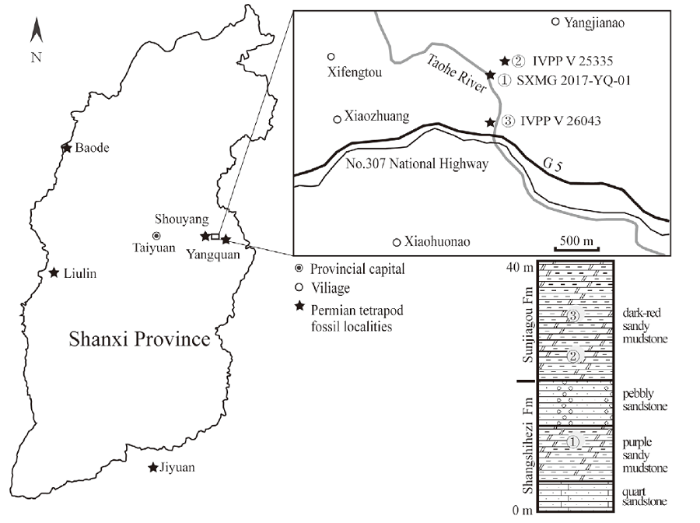

In 2014, a tusked dicynodont snout was collected from the Sunjiagou Formation in Baode, Shanxi, which confirmed the presence of dicynodonts in this stratum. In 2013, a fossil hunter, Bai Zhi-Jun, discovered some bones from Shouyang and Yangquan, Shanxi Province. His initial work led to subsequent discovery of pareiasaur and dicynodont specimens from both the Sunjiagou Formation and Shangshihezi Formation. In this paper, we will briefly describe a new pareiasaur specimen and a new dicynodont specimen from Shouyang, Shanxi and discuss their implications for biostratigraphy and biogeography (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1

新窗口打开|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT

新窗口打开|下载原图ZIP|生成PPTFig. 1The Permian tetrapod fossil localities and stratigraphic column of the fossil horizon in Shouyang, Shanxi

Institutional abbreviations HGM, Henan Geological Museum, Zhengzhou, Henan; IVPP, Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing; SXMG, Shanxi Museum of Geology, Taiyuan, Shanxi.

1 Geological background

The Shangshihezi Formation is late Guadalupian to early Lopingian in age, while the Sunjiagou Formation is approximately late Lopingian in age (Liu, 2018). Both formations are composed of fluvial and lacustrine deposits, although the Sunjiagou Formation has interbedded by marine facies in southern margin of the North China Block. The Shangshihezi Formation is characterized by purple-colored mudstone, and the Sunjiagou Formation is dominated by dark red mudstone.The specimens studied in this paper were collected from a valley eroded by the tributary of the Taohe River, near the border of Shouyang and Yangquan and close to the intersection of the Yun-Wen Road with the G5 Highway (Fig. 1). SXMG 2017-YQ-01, including a right ilium, some vertebrae and ribs, was collected from purple sandy mudstone near the top of Shangshihezi Formation (Locality 17P), whereas IVPP V 26043, a broken skull, was collected from the dark red mudstone from the lower part of the Sunjiagou Formation (Locality 18P5). Another dicynodont specimen, IVPP V 25335, was produced from near the base of the Sunjiagou Formation (Locality 18P3), which will be described elsewhere. The three localities are close in their stratigraphic level and geographic distance.

2 Systematic paleontology of SXMG2017-YQ-01

Parareptilia Olson, 1947Pareiasauria Seeley, 1888

Pareiasauria indet.

Material SXMG 2017-YQ-01, a right ilium, several dorsal vertebrae and ribs.

Locality and horizon 17P, Shouyang; purple sandy mudstone; near the top of the Shangshihezi Formation.

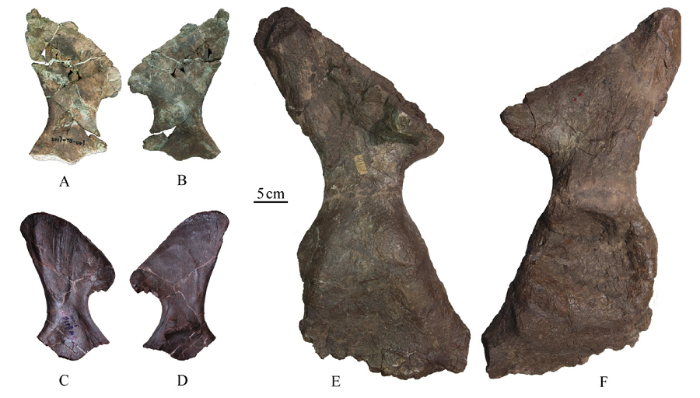

Description The vertebrae and ribs are poorly preserved, therefore, only the ilium is worthy of description. The right ilium is nearly complete aside from the anterodorsal margin of blade (Fig. 2). The blade is thin and nearly flat, with a posterior process much shorter than the anterior one. The anterodorsal portion of the blade is fragmentary, and the posterior iliac margin is pointed posteroventrally. The dorsal margin of the blade is convex dorsally. The lateral surface of the anterior process is concave, but the anteroventral margin is slightly everted. The ilium narrows at the neck, the anterior margin of neck is nearly straight whereas the posterior margin is sharply concave. In medial view, the crista sacralis is not well developed, therefore the number of sacral ribs cannot be determined.

Fig. 2

新窗口打开|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT

新窗口打开|下载原图ZIP|生成PPTFig. 2Comparison of ilia of pareiasaurs

A-B. SXMG 2017-YQ-01 from Shouyang, Shanxi; C-D. HGM 41HIII0434 (Honania complicidentata) from Jiyuan, Henan; E-F. IVPP V 2717 (holotype of Shihtienfenia permica) from Baode, ShanxiA, C, E. in medial views; B, D, F. in lateral views

The supraacetabular buttress of the ilium is well developed, forming a prominent tuber on the lateral side. Anterior to the acetabulum, a shallow rugose groove is present. The dorsal outline of the acetabulum is approximately circular. The ventral side of ilium is slightly projecting medioventrally.

Discussion Although there are seven named Chinese pareiasaur species, complete ilia are known only for Honania complicidentata and Shihtienfenia permica (Young and Yeh, 1963; Xu et al., 2015). In H. complicidentata, the anterior iliac process is laterally concave and its anteroventral margin is slightly everted, the dorsal margin is slightly convex. In S. permica, the anterior portion of the iliac process is strongly everted as a convex surface and the dorsal margin is slightly concave. Anterodorsal expansion of the iliac blade is seen in many derived cynodont and dicynodont synapsids from the Permian and Triassic (Turner et al., 2015). The iliac blade is greatly expanded anteriorly in Bradysaurus, Embrithosaurus, Pareiasuchus, Shihtienfenia, Pareiasaurus, Scutosaurus and Elginia. In Pareiasuchus, Shihtienfenia, Pareiasaurus, Scutosaurus and Elginia, the anteroventral margin of iliac blade is very strongly everted (Lee, 1997).

The ilium of SXMG 2017-YQ-01 is identical as the ilium of H. complicidentata in features mentioned above although its neck is slightly wider, so this specimen is more similar to the ilium of Honania than that of Shihtienfenia, and thus it may represent a species closely related to H. complicidentata. So this new specimen indicates that Honania or a closely related taxon may be present in Shouyang, but precise identification requires more informative material.

3 Systematic paleontology of IVPP V 26043

Dicynodontia Owen, 1860Cryptodontia Owen, 1860

Cryptodontia indet.

Material IVPP V 26043, an incomplete skull.

Locality and horizon 18P5, Shouyang; dark-red sandy mudstone; the lower part of the Sunjiagou Formation.

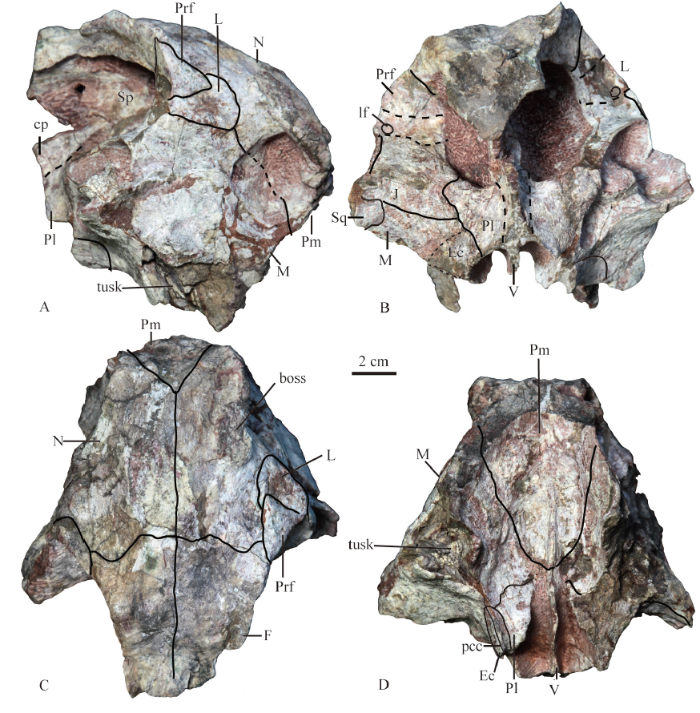

Description The only preserved specimen is an incomplete anterior portion of a skull. The anterior tip of the premaxilla and tusks are incomplete (Fig. 3). The preserved length is 12 cm, and a complete skull basal length is estimated as 25 cm. The external naris is anteroposteriorly elongated and it forms an oval concave area with an excavation which lies ventral and slightly posterior to the external naris.

Fig. 3

新窗口打开|下载原图ZIP|生成PPT

新窗口打开|下载原图ZIP|生成PPTFig. 3A ‘cryptodontian’ dicynodont from the Sunjiagou Formation, Shouyang, Shanxi, IVPP V 26043

A. lateral view; B. posterior view; C. dorsal view; D. ventral view

Abbreviations: cp. cultriform process; Ec. ectopterygoid; F. frontal; J. jugal; L. lacrimal; lf. lacrimal foramen; M. maxilla; N. nasal; pcc. postcaniniform crest; Pl. palatine; Pm. premaxilla; Prf. prefrontal;

Sp. sphenoid; Sq. squamosal; V. vomer

The premaxilla is incomplete, and it is uncertain whether paired anterior ridges on palatal surface were present. The posterior median ridge increases in height and breadth posteriorly, with maximal size achieved immediately anterior to the palatine pads. This ridge continues into the interpterygoid region as the mid-ventral plate of the vomer. There are paired elongate depressions lateral to the ridge, without trace of the lateral anterior ridge. In lateral view, the premaxilla contacts the maxilla below the external naris. Posterodorsally, it forms a V-shaped suture with the nasal. The border of the septomaxilla is unclear.

The maxilla bears a well-developed caniniform process housing a broken tusk of ~15 mm in diameter. The caniniform process slightly bulges outwards along its lateral surface. Dorsally, the maxilla contacts the lacrimal and the nasal. Posteriorly, it contributes to the lateral surface of the anterior part of the zygomatic arch, which is formed together with the jugal dorsally and the squamosal ventromedially. The squamosal seems have no lateral exposure here (Fig. 3B). A sharp postcaniniform crest is present on the right side while this structure is incomplete on the left side. Anterior to the left caniniform process is an incomplete, but sharp palatal rim. Posteriorly and dorsally, there are two straight sutures with the jugal. Medially, the maxilla sutures with the palatine and the ectopterygoid. The labial fossa is absent.

The nasal is almost complete except for the broken dorsal surface. It has a long mid-nasal suture which separates the premaxilla from the frontals. A long and narrow boss is partially present on the right side, but the left one is not preserved. It is unclear if the two bosses were confluent or well separated. The nasal boss is only slightly beyond the posterior border of the external narial excavation, and is far from the orbit rim. Posteriorly, the nasal has a slightly curved suture with the frontal. The ridge across the nasofrontal border is absent.

The lacrimal is a concave bone on the snout surface that only forms small part of the anterior orbital margin. Its ventral margin sutures with the maxilla and forms an anteroposteriorly directed ridge, and a fossa is formed mainly by the lateral surface of the lacrimal. Anteriorly, it is separated from contacting the naris by the nasal. Within the orbit, the lacrimal is perforated by a single, large lacrimal foramen.

The prefrontal is a small triangular bone that is limited to the anterodorsal orbital margin. It is thickened as a boss, protruding more laterally than the lacrimal. The posterior parts of the frontals are not preserved, and their dorsal surfaces are weathered. The frontal is narrow and restricted to the interorbital region. It forms most part of the dorsal margin of the orbit.

The jugal is incomplete, only the portion making up the ventral wall of the orbit is preserved. It is bordered mainly by the maxilla and medially by the palatine.

The vomer is exposed as a narrow, rod-like element within the interpterygoid vacuity in ventral view. The posterior portion is not preserved. The palatine is exposed ventrally in the form of a palatine pad. Anteriorly, it contacts the maxilla, approaches the premaxilla but does not reach it. The choanal portion of the palatine extends dorsally to meet the vomer. The ectopterygoid is a small element lateral to the palatine.

Discussion This fossil can be distinguished from all Chinese dicynodonts other than Daqingshanodon by the presence of postcaniniform crest and distinct nasal boss near the posterodorsal margin of external nares. The postcaniniform crest was alleged to be present in Daqingshanodon (Kammerer et al., 2011), but it is only weakly developed on the left side, and is less distinct than in this specimen. These two features are present in all ‘cryptodontian’ other than Bulbasaurus (Kammerer and Smith, 2017). Although sometimes Daqingshanodon was referred to a monophyletic Cryptodontia (Kammerer et al., 2011; Kammerer and Smith, 2017; Kammerer, 2018), it usually occupies a stemward position in the clade and never falls within Geikiidae, Oudenodontidae, or Rhachiocephalidae. IVPP V 26043 has long nasal bosses like ‘cryptodonts’ such as Australobarbarus, Oudenodon, Odontocyclops, and Aulacephalodon, and could be the first representative of the three main ‘cryptodont’ subclades from China.

4 Conclusion

The pareiasaur from the Shangshihezi Formation may expand the distribution of the Jiyuan Fauna (Honania Assemblage Zone), but the presence of Honania needs to be confirmed by additional material. Also, this assemblage might extend to the lower part of the Sunjiagou Formation, but additional specimens are needed to confirm this. The younger Shihtienfenia Assemblage is only known from the upper part of the Sunjiagou Formation (Wang et al., 2019). The boundary between the two assemblage zones is still uncertain, but could be within the Sunjiagou Formation.This first dicynodont from the Sunjiagou Formation may represent an occurrence of a ‘cryptodont’ subclade that was previously unknown in China. Recently, some new dicynodonts were reported from the Naobaogou Formation of Nei Mongol, and some could be referred to Jimusaria or even J. sinkianenis from Guodikeng Formation of Xinjiang (Liu, 2019). The Naobaogou Formation is generally regarded as a synchronous deposition as the Sunjiagou Formation. If this is true, there is the potential to find taxa such as Jimusaria, Daqingshanodon in Shanxi.

参考文献 原文顺序

文献年度倒序

文中引用次数倒序

被引期刊影响因子

[本文引用: 1]

[本文引用: 1]

[本文引用: 2]

[本文引用: 3]

[本文引用: 1]

[本文引用: 3]

[本文引用: 1]

[本文引用: 1]

[本文引用: 2]

[本文引用: 1]

[本文引用: 1]

[本文引用: 1]

[本文引用: 1]

[本文引用: 1]

[本文引用: 1]

[本文引用: 1]

[本文引用: 1]

[本文引用: 1]

[本文引用: 1]