,3,∗∗, Hu Chen

,3,∗∗, Hu Chen ,4,∗∗, Yanhui Liu

,4,∗∗, Yanhui Liu ,1,5,∗∗1College of Physics,

,1,5,∗∗1College of Physics, 2School of Physics and Electronic Science,

3Collaborative Innovation Center for Optoelectronic Semiconductors and Efficient Devices, PenTung Sah Institute of Micro-Nano Science and Technology,

4Research Institute for Biomimetics and Soft Matter, Fujian Provincial Key Lab for Soft Functional Materials Research, Department of Physics,

5Breeding and Reproduction in The Plateau Mountainous Region,

First author contact:

Received:2021-02-18Revised:2021-04-24Accepted:2021-04-29Online:2021-06-04

| Fund supported: |

Abstract

Keywords:

PDF (1087KB)MetadataMetricsRelated articlesExportEndNote|Ris|BibtexFavorite

Cite this article

Caiyun Xiong, Xiaolin Nie, Yixue Peng, Xun Zhou, Yangtao Fan, Hu Chen, Yanhui Liu. Influences of flexible defect on the interplay of supercoiling and knotting of circular DNA

1. Introduction

Circular DNA can develop into physical knots with different complexity facilitated by DNA topoisomerases and knots have been discovered in a wide range of systems, from biopolymers, such as DNA and proteins, to macroscopic objects, such as umbilical cords and catheters [1–3]. Over the past decades, significant advances in experiments and the theory of knots have been made [4–9]. In experiments, knots in DNA or other biopolymers can be tied manually [10], formed spontaneously [11] or by compression [12]; the knot in DNA under tension [13] or in nanochannel can be identified as a bright spot diffusing along DNA via fluorescent labeling [14]. And knots in DNA can also be identified directly via Atomic-force microscopy imaging [15] or nanopore translocation experiment [16].Theoretical works concentrated on knot behaviors under various conditions, such as in a free space [17], in spatial confinement [18], under pulling forces [19], in a crowded environment [20] and with different bending stiffness [21, 22]. Related molecular dynamics simulations were performed on a model of diblock flexible-stiff polymer ring hosting a knot to address a question of how the stiffness of polymer could affect topological properties, such as the position and size of knots within a circular knotted polymer. When both blocks are long enough to accommodate a knot, raising temperature could drive a knot shift from the flexible part to the stiffer one [23].

The dependence of equilibrium knotting properties on the bending rigidity was detected by Monte Carlo simulations. Knotting probability is non-monotonically dependent on knot length of semi-flexible rings, which are taken from rigidity to fully-flexible limit [24]. Effects of intra-chain interactions on knots have been systematically investigated, the results indicated that knots could be tightened by long-range repulsions [25], which could be applied to trap a knot into tight conformations by Langevin dynamics simulations. The strength of intra-chain repulsion was tuned to weakly trap a knot, so that the knot weakly trapped could escape from the trap and was then re-trapped by thermal fluctuations; its switching between tight and loose conformations was referred to as ‘knot breathing' [26].

A tightly knotted portion makes it a preferred substrate for binding and unknotting by type II DNA topoisomerases [27]. Recent Brownian dynamics simulations [28] found that knotted portions in circular DNA could be tightened by supercoiling and became significantly more bent than the remaining portions. The dominant bending angles are around 80°–90° [28], which are comparable with the sharp bending angle resulting in flexible defect and hence the reduction of bending rigidity, twist rigidity and the unwinding of DNA [29–32]. In current works, effects of flexible defect on the interplay of supercoiling and knotting of circular DNA will be detected. Effects of flexible defect on topological states of chiral knotted DNA are first looked at, and then the reduction of twist rigidity and the unwinding of flexible defect are incorporated into the numerical simulations, so that the interplay of supercoiling and knotting of circular DNA can be studied under torsional conditions. At last, the question of how flexible defect affects the knotting probability is addressed by the phase diagram constructed in the phase space of knot length and gyration radius of knotted DNA.

2. Methods of calculations

2.1. DNA model and Monte Carlo simulation procedure

Worm-like chain (WLC) model of DNA has been widely used to predict the linking number distributions in good agreement with those measured in experiments of circular DNAs of 250–10 000 bp size in a wide temperature range of 4 °C–37 °C [33–35]. However, the above experiments and simulations do not rule out the possibility that WLC may fail to describe DNA elasticity at sharper bending conditions, resulting in melted base pairs or base pairs that lose their stacking interactions with its neighboring base pairs. The possibility of excitation of such defect was first pointed out by Crick and Klug [36], recently observed in ≤ 65 bp minicircles, and furthermore proved by molecular-dynamics simulation [37], where the defect is an unstacked base-pair step that allows formation of ≥90° of bending at the defect site [38].In WLC model, a DNA was considered as a discredited chain consisting of N straight segments with segment length b. While the defect resulted from the sharp bending is considered, its total bending energy (E) including the persistence length of B-DNA α and the flexible kink $\alpha ^{\prime} $, and the energy required to excite one flexible defect μ (in kBT unit) can be expressed as the summation of all the vertex energies, $\tfrac{E}{{k}_{{\rm{B}}}T}={\sum }_{i=1}^{N}{E}_{i}({\hat{t}}_{i},{\hat{t}}_{i+1})$, and a single vertex energy Ei connecting two adjacent tangent vectors ${\hat{t}}_{i}$ and ${\hat{t}}_{i+1}$ can be generalized as

Based on equation (

2.2. Topology variables of knotted DNA

Generally, two important variables are used to describe the topology states of closed circular DNA. One is the linking number, Lk, which describes the winding of the complementary strand of DNA about each other, but it is more convenient to use the difference between linking number Lk and that of relaxed DNA (Lk0), ΔLk = Lk − Lk0, than Lk itself. Since both Lk0 and ΔLk are not integer, however, ΔLk can only be differed by integer number.The other is the knot type, K, formed by the double helix axis. The knot type can be identified according to Alexander polynomial Δ(t) at t = −1 and t = −2. During simulation, the change of knot type is prevented by rejecting the trial conformation for which the values of Δ(− 1) and Δ(− 2) have changed [39]. The writhe number of a knotted conformation with a particular knot type can be calculated by ${Wr}=\tfrac{{b}^{2}}{4\pi }{\sum }_{i,j=1,i\ne j}^{N}\tfrac{{\hat{t}}_{j}\times {\hat{e}}_{{ij}}\cdot {\hat{t}}_{i}}{{d}_{{ij}}^{2}}$, where ${\hat{e}}_{{ij}}$ is the unit vector pointing from the jth vertex to the ith vertex and dij is the distance between two vertices [40, 41]. And its corresponding writhe distribution ρ(Wr∣K) can be obtained directly from simulations. The twist of DNA, ΔTw, the difference between the actual twist and relaxed twist of the same circular DNA, which is combined with the writhe distribution with a particular knot type ρ(Wr∣K) by the White's equation, which puts a constraint on the linking number, the writhe and twist of a knotted DNA as ΔLk = Wr + ΔTw. Due to this constraint, the linking number distribution of knotted DNA with a particular knot type ρ(ΔLk∣K) can be obtained from the convolution

While the chain segments are allowed to pass through each other in simulation procedure, the knot type of the chain changes during successive deformations. By calculating the value of the Alexander polynomial Δ(t) at t = −1 and t = −2, different knot type in the equilibrium set of chain conformations can be distinguished, and their corresponding probability ρ(K) can be specified. Combing the probability ρ(K) with the linking number distribution of a particular knot type ρ(ΔLk∣K), an important derivative distributions ρ(ΔLk, K) and the general distribution ρ(ΔLk) can be obtained as the following

To clarify the interplay of supercoiling and knotting of circular DNA and characterize the different degree of compactness and hence of geometrical complexity, a bottom-up method [28, 43] is applied to define the knot length Lknot. Namely, a smaller contour length ℓ is first selected from the knot ring at will. After closing this arc ℓ, its topology is still the same as the overall knot. Moreover, its complementary arc on the knot ring is different from the whole knot topology. Thus, ℓ is identified as the knot length Lknot. Otherwise, ℓ is increased by one segment and the search for a knotted arc starts again. Clearly, the search stops when the knot length is identified.

3. Results and discussions

3.1. Effects of flexible defect on topological states of chiral knotted DNA

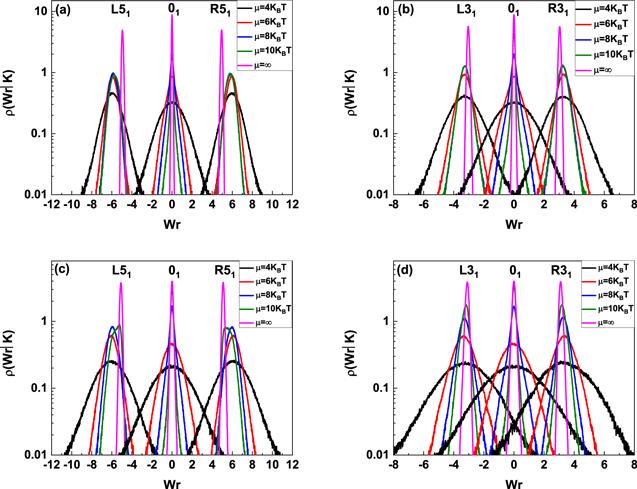

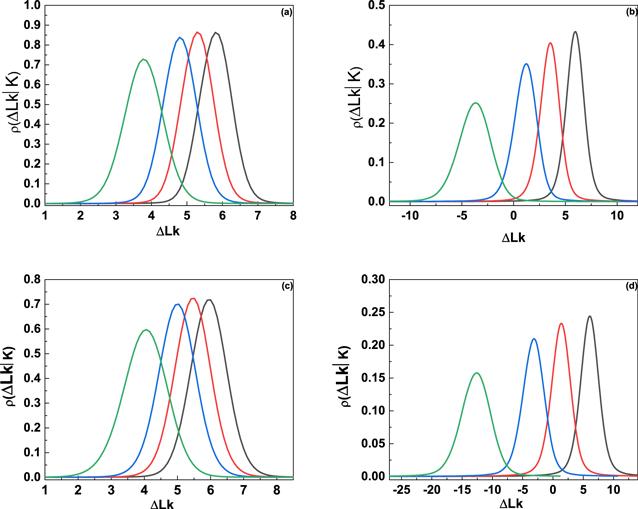

In current simulations, three simplest knots, 31, 41 and 51 are generated, in which knots 31 and 51 are chiral and knot 41 is achiral, R and L are used to indicate right-handed chirality and left-handed chirality, respectively. Their corresponding writhe distribution based on energy equation (Figure 1.

New window|Download| PPT slide

New window|Download| PPT slideFigure 1.Writhe number distributions of knotted DNA with chirality. (a) 80 nm, L51, 01 and R51 knotted DNA; (b) 80 nm, L31, 01 and R31 knotted DNA, (c) 160 nm, L51, 01 and R51 knotted DNA; (d) 160 nm, L31, 01 and R31 knotted DNA. In each figure, from outside to inside, the excitation energies are 4kBT, 6kBT, 8kBT, 10kBT and ∞ (B-DNA), respectively.

Once the writhe distribution ρ(Wr∣K) is obtained by simulation, the linking number distribution can be obtained by equation (

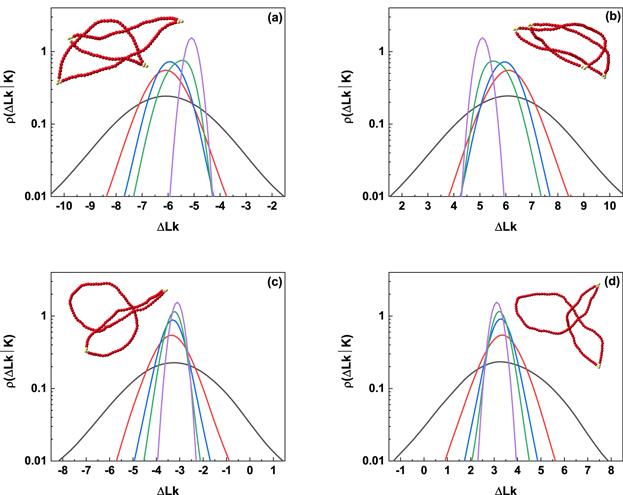

Figure 2.

New window|Download| PPT slide

New window|Download| PPT slideFigure 2.Linking number distributions of knotted DNA with chirality. (a) 160 nm, L51 DNA knot; (b) 160 nm, R51 DNA knot; (c) 160 nm, L31 DNA knot; (d) 160 nm, R31 DNA knot. In each figure, from outside to inside, the excitation energies are 4kBT, 6kBT, 8kBT, 10kBT, and ∞ (B-DNA), respectively. Typical conformations are illustrated in inset of each figure and the excitation energy corresponding to each conformation is 10kBT.

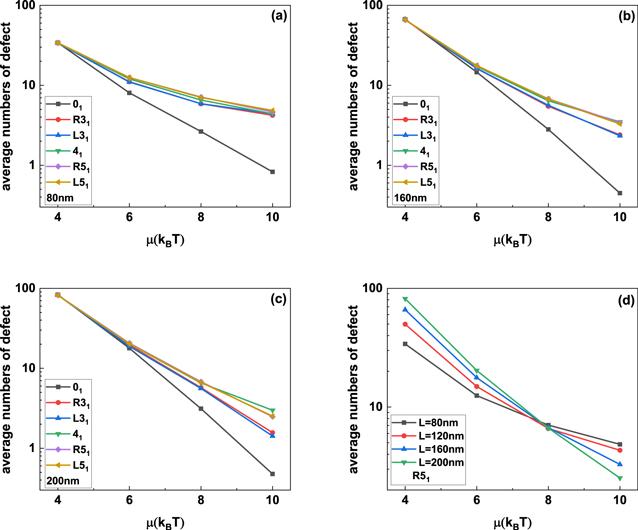

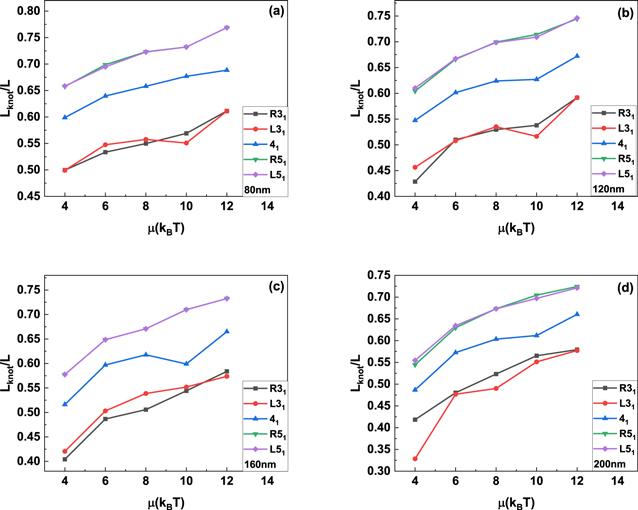

The insets in figure 2 show the typical knotted conformations with a few flexible defects, and the average number of flexible defects in knotted DNA with different knot type as a function of the excitation energy μ is demonstrated in figure 3. Figures 3(a)–(c) indicate that the average number of flexible defect decreases with the increasing excited energy, but the generation of flexible defect is dependent on the counter length of knotted DNA. For knotted DNA with small contour length, when the excited energy is larger than 4kBT, the generation of flexible defect was enhanced by knotting in compared with that of trivial knot 01. With the increasing contour length, knotting can only enhance the generation of flexible defect at relatively large excited energies, at the same time, current simulations indicate that the average number of flexible defect increases with the growing complexity of knotted DNA, but not obviously depend on the chirality of knotted DNA. Figure 3(d) shows the average number of flexible defects for R51 knotted DNA from 80 nm to 200 nm. For excitation energy μ > 8kBT, the average number of flexible defect is inversely proportional to contour length of knotted DNA. When excitation energy μ decreases to 6kBT or even 4kBT, the average number of flexible defects begins to increase with increasing contour length of knotted DNA. At 4kBT, there are about 100 flexible defects in knotted DNA with contour length 200 nm, namely, about half of the knotted DNA is melted. Figures 4(a)–(d) demonstrate the scaled knot length for knotted portion changing with the excited energy μ. For knotted DNA with different contour length ranging from 80 to 200 nm, the scaled knot length reduced with the decreasing excitation energy μ, which indicates that the decreasing excited energy μ enhances the tightness of knot portion in knotted DNA, which generally facilitates the binding of the type IIA DNA topoisomerase to unknot the knotted DNA. The scaled knot length does not obviously depend on the chirality, and even overlaps together for complex knotted DNA with different chirality. At a fixed excitation energy μ, the scaled knot length of knotted DNA increases sharply as the knot complexity grows.

Figure 3.

New window|Download| PPT slide

New window|Download| PPT slideFigure 3.(a)–(c) Average numbers of flexible defects in knotted DNA with different knot type changing with excitation energy μ. (d) The average number of defects in R51 DNA knot as a function of the excitation energy μ.

Figure 4.

New window|Download| PPT slide

New window|Download| PPT slideFigure 4.The average knot length scaled by contour length of knotted DNA changing with the excitation energy μ. The DNA knot types are R31, L31, 41, R51 and L51, respectively.

3.2. Effects of reduced twist rigidity and unwinding of the flexible defect

The aforementioned discussions clearly addressed that the flexibility of flexible defects increases the withes of the writhe distribution, and hence those of the linking number distribution. In addition to reduction of bending rigidity, the flexible defect also leads to the reduced twist rigidity and the unwinding of DNA, which will further increase the variances of linking number distribution. Generally, the conditional twist distribution in the presence of n flexible defects ρn(ΔTw) is still a Gaussian distribution [29] with variancesThe numerical linking number distributions ρ(ΔLk∣K) obtained according to equation (

Figure 5.

New window|Download| PPT slide

New window|Download| PPT slideFigure 5.Effects of unwinding angle on the linking number distributions of L51 DNA knot. (a) 80 nm, μ = 8kBT; (b) 80 nm, μ = 4kBT; (c) 160 nm, μ = 8kBT; (d) 160 nm, μ = 4kBT. In each figure, from right to left, the unwinding angle per defect is φ = 0°, 26°, 51°, and 103°.$C^{\prime} $ = $\tfrac{C}{4}=18.75\,\mathrm{nm}$ was used in the calculation.

3.3. Effects of flexible defect on the knotting of circular DNA

In the aforementioned section, our discussions concentrate on effects of flexible defects on the knotted DNA with particular knot type, namely, the change of knot type was prevented during simulations. In this section, the chain segments are allowed to pass through each other during successive conformations transition in simulations, so that the equilibrium distributions probability of knots, ρ(K), can be specified from the constructed equilibrium set of chain conformations and partial data is summarized in table 1. The equilibrium distributions probability for trivial knot (01) is dominant over that of nontrivial knots. At a fixed excited energy, the equilibrium distributions probability decrease sharply when the knot complexity grows.Table 1.

Table 1.The equilibrium distribution probability of knots with 800 nm in length at different excited energy μ. ∑ indicates the summation of the equilibrium distribution probability of the nontrivial knotted DNA at different excitation energy μ.

| knot type K | μ = 4 | μ = 6 | μ = 8 | μ = 10 | μ = ∞ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01 | 0.993 452 | 0.982 434 | 0.992 174 | 0.996 545 | 0.997 500 |

| 31 | 0.005 723 | 0.015 284 | 0.007 259 | 0.003 257 | 0.002 444 |

| 41 | 0.000 049 | 0.001 439 | 0.000 336 | 0.000 099 | 0.000 056 |

| 51 | 0.000 000 | 0.000 298 | 0.000 142 | 0.000 000 | 0.000 000 |

| 52 | 0.000 776 | 0.000 248 | 0.000 089 | 0.000 000 | 0.000 016 |

| ∑ | 0.006 548 | 0.017 566 | 0.007 826 | 0.003 355 | 0.002 500 |

New window|CSV

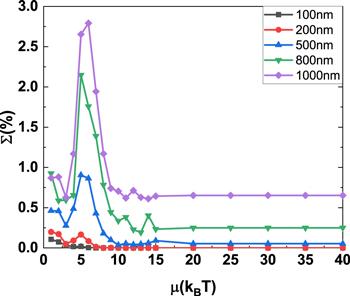

The summation (Σ) of equilibrium distributions probability (ρ(K)) for nontrivial knotted DNA with different contour length changing with excitation energy μ is demonstrated in figure 6 and does not change with excitation energy μ monotonically. Specifically, Σ has a maximum for an intermediate value of excitation energy μ around 5kBT as the contour length for knotted DNA is increased from 100 to 1000 nm. The maximum value of Σ grows rapidly with the contour length for knotted DNA.

Figure 6.

New window|Download| PPT slide

New window|Download| PPT slideFigure 6.The summation of the equilibrium distributions of the nontrivial knotted DNA changing with excitation energy μ.

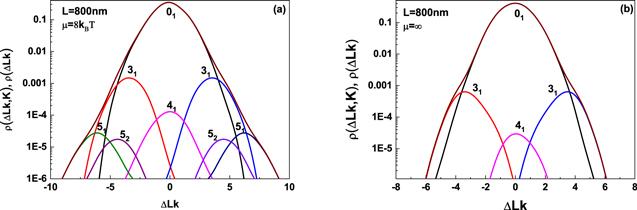

According to equation (

Figure 7.

New window|Download| PPT slide

New window|Download| PPT slideFigure 7.Simulated distribution of ρ(△Lk, K) and ρ(△Lk), these simulations are carried out for circular DNA with 800 nm in length at excited energy 8kBT and ∞. The distribution ρ(ΔLk, K) corresponding to different knots is indicated by separate peaks and the distribution ρ(ΔLk), the summation of ρ(ΔLk, K) over K, is represented by wine line.

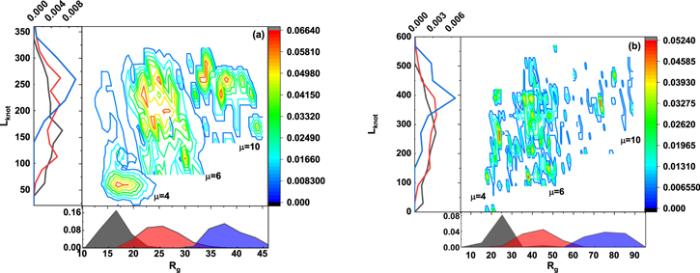

Three characteristic parameters, namely gyration radius (Rg), knot length (Lknot) and excitation ennergy μ of flexible defect are used to further describe the supercoiling and knotting of circular DNA, and their interplay for knotted DNA with contour length 500 nm and 800 nm is summarized in the phase diagram shown in figure 8(a)∼(b), respectively, which are constructed in phase space of gyration radius (Rg) and knot length (Lknot). Their corresponding distributions are shown in the side panels and the distribution probability ρ(Lknot, Rg) for different excitation energy is demonstrated in the central panel.

Figure 8.

New window|Download| PPT slide

New window|Download| PPT slideFigure 8.The central panel corresponds to the contour maps of the probability distribution ρ(Rg, Lknot) of knotted DNA for three different excitation energies 4kBT, 6kBT and 10kBT. The side panels show the marginal distribution of Rg and Lknot. The contour length for knotted DNA in (a) and (b) is 500 nm and 800 nm, respectively.

A recent work [24] also reported similar phase diagram based on the control of bending rigidity ranging from the rigid to the fully-flexible limit, and its results indicated that knot length (Lknot) anticorrelated with gyration radius (Rg), and their anticorrelation was particularly evident for the smallest bending rigidity shown in their results. This property was rationalized by the competition between entropy and bending energy, namely, reducing the knot length is equivalent to increasing the length of the complementary unknotted arc and, because this enjoys a larger conformational freedom, it ultimately reflects in a larger gyration radius of the ring.

In comparison with the findings mentioned by the recent work [24], the phase diagrams in figures 8(a), (b) do not indicate obvious anticorrelation between knot length (Lknot) and gyration radius (Rg), and contour length of knotted DNA ranging from 500 to 800 nm has strong influences on the phase diagrams. The absence of anticorrelation and the dependence of phase diagrams on contour length of knotted DNA could attribute to the local generation of flexible defect in knotted DNA, which has a remarkably high probability to be within the knot portion [23], so that the bending energy could be released and the competition between bending energy and entropy is inhibited. With the increasing contour length, few flexible defects are excited, so that the bending rigidity recover to the canonical one, at which knot length (Lknot) anticorrelate with gyration radius (Rg) as reported by [24].

4. Conclusions

In the current work, a Monte Carlo simulation is applied based on flexible defect excitations to predict the roles of flexible defects in the interplay of supercoiling and knotting of circular DNA. Flexible defects obviously enhance the fluctuation of linking number distribution of knotted DNA and hence its supercoiling. The decreasing excitation energy makes the knotted portion more compact. The reduction of twist rigidity has no obvious influence on the distribution ρ(ΔLk∣K), by contrast, the increasing unwinding angle not only enhances the variance of this distribution, but also leads to a drift of linking number distribution to lower values. The summation of equilibrium distribution probability for nontrivial knotted DNA with different contour length does not change with excitation energy monotonically and has a maximum at an intermediate value of excitation energy around 5kBT, the maximum value increases with the increasing contour length of knotted DNA. A phase diagram in phase space of knot length and gyration radius of knotted DNA is constructed and the phase diagrams for knotted DNA with different contour length indicated that knot length did not anticorrelate with the gyration radius of knotted DNA, which could be attributed to the flexible defect in the knot portion. The flexible defect results in a reduction of bending rigidity and hence the release of bending energy, so that the competition between entropy and bending energy is inhibited.Reference By original order

By published year

By cited within times

By Impact factor

DOI:10.1146/annurev.biophys.093008.131412 [Cited within: 1]

DOI:10.1073/pnas.90.11.5307

DOI:10.1126/science.277.5326.690 [Cited within: 1]

DOI:10.1073/pnas.032095099 [Cited within: 1]

DOI:10.1073/pnas.0409323102

DOI:10.1073/pnas.0907524106

DOI:10.1038/35022623

DOI:10.1016/j.jmb.2011.02.056 [Cited within: 1]

DOI:10.1103/PhysRevLett.91.265506 [Cited within: 1]

DOI:10.1209/epl/i2006-10312-5 [Cited within: 1]

DOI:10.1073/pnas.1105547108 [Cited within: 1]

DOI:10.1103/PhysRevLett.91.265506 [Cited within: 1]

DOI:10.1134/S0965545X16060079 [Cited within: 1]

DOI:10.1103/PhysRevLett.98.058102 [Cited within: 1]

DOI:10.1038/nnano.2016.153 [Cited within: 1]

DOI:10.1103/RevModPhys.79.611 [Cited within: 1]

DOI:10.1021/acs.macromol.5b00280 [Cited within: 1]

DOI:10.1021/jp071940+ [Cited within: 1]

DOI:10.1021/acs.macromol.5b01323 [Cited within: 1]

DOI:10.1021/ma5006414 [Cited within: 1]

DOI:10.1021/mz300493d [Cited within: 1]

DOI:10.1021/acs.macromol.6b00712 [Cited within: 2]

DOI:10.1039/C7SM00643H [Cited within: 4]

DOI:10.1021/acs.macromol.6b01653 [Cited within: 1]

DOI:10.3390/polym9020057 [Cited within: 1]

DOI:10.1038/nature06396 [Cited within: 1]

DOI:10.1073/pnas.1016150108 [Cited within: 3]

DOI:10.1103/PhysRevE.79.041926 [Cited within: 4]

DOI:10.1021/acs.jpcb.7b07701

DOI:10.1016/S1097-2765(04)00210-2

DOI:10.1063/1.4991689 [Cited within: 1]

DOI:10.1016/0022-2836(84)90404-2 [Cited within: 1]

DOI:10.1073/pnas.72.11.4275

DOI:10.1093/nar/25.7.1412 [Cited within: 1]

DOI:10.1038/255530a0 [Cited within: 1]

DOI:10.1016/j.str.2006.08.004 [Cited within: 1]

DOI:10.1093/nar/gkm1125 [Cited within: 1]

DOI:10.1073/pnas.96.23.12974 [Cited within: 1]

DOI:10.1016/0301-4622(93)E0094-L [Cited within: 1]

DOI:10.1016/S0006-3495(04)74357-X [Cited within: 1]

DOI:10.1006/jmbi.1993.1465 [Cited within: 1]

DOI:10.1143/PTPS.191.192 [Cited within: 1]